Abstract

Background

Maintaining blood supply is essential since blood transfusions are lifesaving in many conditions. The 2003 infectious outbreak of SARS-CoV had a negative impact on blood supply. This study aimed to measure donor attendance and blood demand in order to help find efficient ways of managing blood supply and demand during the COVID-19 pandemic and similar public emergencies in the future.

Materials and methods

Data from donor attendance, mobile blood drives and blood inventory records were retrospectively obtained for the period between 1 September 2019 and 1 May 2020 to assess the impact of COVID-19 on donor attendance and the management of blood supply and demand in King Abdullah Hospital, Bisha, Saudi Arabia. Data were analysed using SPSSStatistics, version 25.0. Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages.

Results

After imported cases of COVID-19 were reported in Saudi Arabia, donor attendance and blood supply at blood bank-based collections showed a drop of 39.5%. On the other hand, blood demand during the same period was reduced by 21.7%.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact on donor attendance and blood supply and adversely affected blood transfusion services. Guidelines that prioritize blood transfusion should prepare at the beginning of emergencies similar to this pandemic. Close monitoring of blood needs and blood supply and appropriate response is essential for avoiding sudden blood shortage. An evidence-based emergency blood management plan and flexible regulatory policy should be ready to deal with any disaster and to respond quickly in the case of blood shortage.

Keywords: Blood supply management, Blood demand, Blood donation, COVID-19, Patient blood management

1. Background

In December 2019, an unknown viral infection was discovered in Wuhan city, China [1]. The virus rapidly spread worldwide [2,3], and many patients reported symptoms of pneumonia [4]. In late December, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified the pathogen causing this pneumonia as a new strain of coronavirus; this novel coronavirus was named by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses as ‘severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2’ (SARS-CoV-2), and its associated disease was named by the WHO as ‘coronavirus disease 2019’ (COVID-19). On 31 January 2020, the WHO announced the outbreak of COVID-19 as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern; it has since become a pandemic [5]. As of 26th May, 5,611,597 cases have been documented worldwide, and 348,330 patients have died due to the COVID-19 pandemic according to numbers updated daily by the WHO. This pandemic has had a profound effect on health services, including blood donation (BD) and blood supply. BD has remained the primary source of blood and blood components worldwide. The availability of safe and adequate blood and blood components is critical for the treatment of many patients [6]. The blood transfusion services (BTS) in the study area are dependent on hospital blood banks that are responsible for blood supplies and blood testing. The primary sources of donated blood are direct donation (mainly patients’ relatives), voluntary non-remunerated donors, and mobile blood drives [7]. Maintaining blood supply is essential because blood transfusions are lifesaving in many situations. The 2003 infectious outbreak of SARS-CoV had a negative impact on BD and blood supply [8]. In a pandemic situation like COVID-19, BTS face challenges to delivering a stable and adequate supply of blood due to decreasing blood donations. Fortunately, the transmission of SARS-CoV through transfusion has not been reported [[9], [10], [11], [12]], and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not recommend testing donors or donated blood for SARS-CoV-2. However, blood banks should take precautionary measures to minimize any chance for transmitting SARS-CoV-2 between the blood bank staff and donors and between donors themselves because there is still a theoretical chance of blood transmitting SARS-CoV [13,14]. These precautions include appropriate personal protective equipment, physical distancing between the donors [15], checking donor body temperature, public health measures, and standard laboratory biosafety practices [16,17]. Blood and blood components are continuously needed during the pandemic for patients with blood diseases, cancers, trauma, and emergency surgeries. Without proper management of blood supply and demand, hospitals will face a shortage of blood, with the result that many patients may die or suffer unnecessarily. The information provided by this study will be vital in planning for proper management of blood supply and demand to avoid blood shortage and to help donors donate blood safely during a pandemic. This study aimed to measure donor attendance and blood demand in order to help find efficient ways of managing blood supply and demand during the COVID-19 pandemic and similar public health emergencies in the future.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and setting

A cross-sectional study was conducted in the blood bank department at King Abdullah Hospital, Bisha, Saudi Arabia, between 1 September 2019 and 1 May 2020. King Abdullah Hospital is the tertiary hospital in Bisha and serves a wide range of populations in 240 villages. Blood donor attendance, the volume of blood supply, and blood demand before and during the COVID-19 pandemic were estimated and assessed to aid proper management of blood supplies to avoid blood shortage during this pandemic.

2.2. Data collection and procedure

Data were retrospectively obtained from donor attendance records, mobile blood drives and blood inventory records between 1 September 2019 and 1 May 2020 (four months before and four months after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic). The data included the number of donated units of blood, sources of donated blood, and the number of blood units released for transfusion.

2.3. Data analysis

Data were analysed using SPSSStatistics, version 25.0, to assess donor attendance and the management of blood supply and demand. Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages.

2.4. Ethical clearance

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of King Abdullah Hospital, Bisha, Saudi Arabia.

3. Results

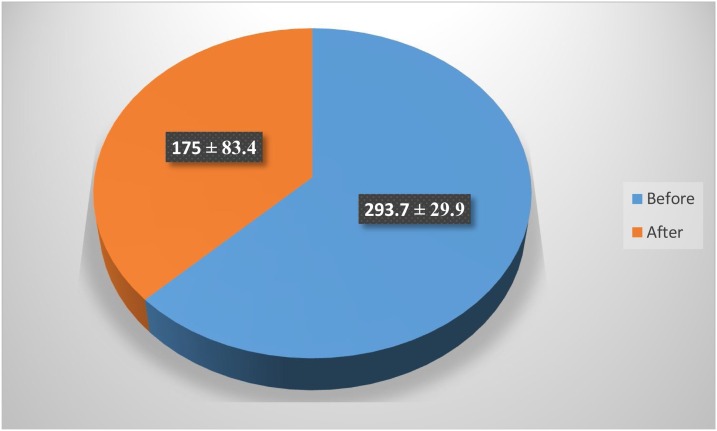

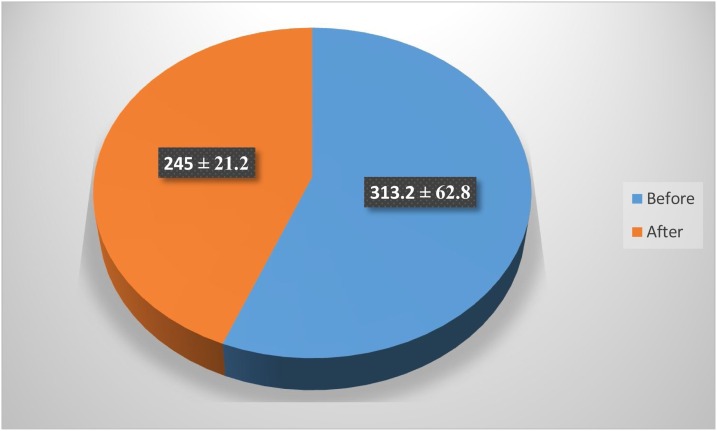

The blood bank department monitors the monthly donated blood in the King Abdullah Hospital. The amount of blood collected in the last four months before the pandemic spread outside China was 1350 units. All the collected blood was from blood bank-based collections except for September, in which 117 units were collected from mobile blood drives that collected at donors’ homes to cover the drop in blood supply (Table 1 ). In January and February 2020, collected blood numbered 252 and 267 units, respectively. All collected blood was from blood bank-based collections. The blood collected from blood bank-based collections in March and April 2020 after COVID-19 arrived in Saudi Arabia numbered 234 and 116 units, respectively, while the blood collected by mobile blood drives at donors’ homes numbered 26 and 114 units, respectively (Table 2 ). The mean ± standard deviation amount of blood collected by blood bank-based collections before COVID-19 arrived in Saudi Arabia was 293.7 ± 29.9 units per month while the mean ± standard deviation amount of blood collected after COVID-19 arrived in Saudi Arabia on 2 March 2020 was 175 ± 83.4 units per month (Fig. 1 ). This notable drop in blood supply was equivalent to 39.5 % of pre-COVID-19 levels. All collected blood was released and delivered for transfusion (Fig. 2 ). The mean ± standard deviation amount of blood utilized in the period before COVID-19 was 313.2 ± 62.8 units per month, while the mean ± standard deviation amount of blood utilized after COVID-19 arrived in Saudi Arabia was 245 ± 21.2 units per month (Fig. 3 ). The reduction in blood demand during this time period was equivalent to 21.7 %.

Table 1.

The volume and sources of blood supply before COVID-19 pandemic.

| Month | Blood supply/unit |

|

|---|---|---|

| Blood bank-based collections | Mobile blood drives | |

| September 2019 | 310 | 117 |

| October 2019 | 317 | 0 |

| November 2019 | 328 | 0 |

| December 2019 | 288 | 0 |

Table 2.

The volume and sources of blood supply during COVID-19 pandemic.

| Month | Blood supply/unit |

|

|---|---|---|

| Blood bank-based collections | Mobile blood drives | |

| January 2020 | 252 | 0 |

| February 2020 | 267 | 0 |

| March 2020 | 234 | 26 |

| April 2020 | 116 | 114 |

Fig. 1.

The mean ± standard deviation units per month of blood bank-based collections before and after the COVID-19 arrived in Saudi Arabia.

Fig. 2.

Blood demand in units by month before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fig. 3.

The mean ± standard deviation units of blood demand per month before and after COVID-19 arrived in Saudi Arabia.

4. Discussion

Blood and blood components are an essential part of emergency preparedness, and neither can be synthesized nor stored for long periods, especially platelets. The shelf life of red blood cells is up to 42 days, while the shelf life of platelets is only five days [18,19]. So, continuous replenishment of the blood supply is crucial. Proper planning of blood supply management is essential during pandemics. In the present study, month-to-month blood supply and blood demand were analysed for the four months before and four months after COVID-19 arrived in Saudi Arabia. The blood collected in the blood bank department in the last four months before the COVID-19 pandemic covered demand except for September 2019, in which demand exceeded BD by 117 units; this gap was covered by mobile blood drives that collected at donors’ homes. Most of the donors in this study were voluntary non-remunerated donors who are likely to be motivated to continue donations during pandemics. Two months after the beginning of the pandemic in Wuhan city in late December 2019, the blood collected by blood bank-based collections did not show any deficit, because COVID-19 had not yet been imported to Saudi Arabia.

After confirmation of the first COVID-19 case in Saudi Arabia on 2 March 2020, the blood bank department noticed a drop in blood supply of 39.5 %. This finding is consistent with a recent study conducted by the American Red Cross [20]. This drop, combined with the ongoing need for blood to maintain emergency and urgent care services for patients and the planned use of convalescent plasma for the treatment of patients of COVID-19 as announced by the FDA, could trigger a critical blood shortage. The drop in blood supply in this study may be explained by the reduction in donors arriving for scheduled appointments due to donor fear of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 at a hospital blood bank [21,22], as well as cancellation of many mobile blood drives due to the closed educational system and employment campuses [23]. Fortunately, this drop in blood supply was balanced by the reduction in blood demand, communication with regular volunteer donors through their private social media encouraging them to donate at the blood bank, and organization of mobile blood drives at donors’ homes after coordination with the donors and application of all COVID-19 safety precautions. All collected blood was released and delivered for transfusion. The release of all donated blood for transfusion indicates that no reserve blood remains in the blood bank, so that any emergency need for blood will be solved either by the allocation of blood stocks of neighbouring hospitals’ blood banks or direct donation/mobile blood drives at donors’ homes after coordination through social media. The blood bank team makes requests to the community to donate blood regularly to help maintain the blood supply and to cover the gap between blood supply and blood demand. The mobile blood drives target donors at their homes as major mobile drive sites are closed, such as high schools, universities, and offices. With the primary finding that blood demand dropped by 21.7 % units per month. This reduction in blood demand during the pandemic is consistent with what was observed in the SARS epidemic in Beijing (April to June 2003) and in Toronto, Ontario, Canada (2003). The reduction in blood demand during the current pandemic is primarily due to reduced hospital admissions, decreased number of trauma injuries due to lockdown and social distancing, postponed elective surgeries, and reserving blood transfusions for lifesaving only.

This study revealed that donor attendance and blood supply are negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitals face many challenges in maintaining stable and adequate blood supply, as shown in previous outbreaks of other coronaviruses [8,[24], [25], [26]]. Many measures should be implemented to overcome these challenges to ensure a stable and adequate blood supply. These measures may include using public media to educate and motivate people for BD and to reassure donors about the availability of safe and accessible options for BD through an appointment system, mobile blood drives at donors’ homes, monitoring of emergency blood supplies, proper management of the available blood, appropriate management of coagulopathy, treatment of anaemias with appropriate pharmacological agents, postponement of elective surgeries where that would not lead to more complex and urgent medical situations, utilization of blood only for emergency conditions and using effective blood conservation methods [27] such as patient blood management (PBM) [28,29]. PBM involves improved blood utilization [30] and reducing the need for blood transfusions while producing similar or better clinical outcomes. Thus, the practice of PBM methods will help safeguard blood stocks and is highly advisable [31]. Blood bank specialists must communicate with clinicians to ensure that blood is only used in emergency and urgent conditions. Hospitals’ plans for maintaining BTS during a pandemic need to include protecting the staff and blood donors, recruiting and motivating voluntary non-remunerated donors to regularly donate until emergency conditions pass, and maintaining enough stock of reagents and consumable items. In the case where a blood shortage happens even after these measures, the shortage can be managed by allocation of blood stocks of neighbouring hospitals’ blood banks [32].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact on donor attendance and blood supply and adversely affected BTS, with the result that the blood transfusion staff faced challenges in maintaining the balance between blood demand and blood supply through the organization of mobile blood drives at donor’s homes and communication with regular volunteer donors through their private social media to come to the blood bank for donation. Effective communication strategies between the blood bank staff, suppliers, clinicians, donors and the public about pandemic-related news and bloodstock are needed. Guidelines that prioritize blood transfusion during a disaster should focus on preparing at the beginning of any emergency like this pandemic. Close monitoring of blood needs and blood supply and appropriate response are needed to avoid sudden blood shortage, particularly for blood components with a short shelf life, such as platelets. BTS should be integrated into the national COVID-19 planning system to work in coordination. The blood transfusion department should make an evidence-based emergency blood management plan and have flexible regulatory policies in place to be ready for disasters and to respond quickly if a blood shortage happens. Regular public awareness campaigns on COVID-19, the safety of the BD process, and the need for regular BD to maintain stable and adequate reserves of the blood are recommended.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Institutional Review Board of King Abdullah Hospital and gratefully acknowledges the blood bank department staff for providing the study data.

References

- 1.Lu H., Stratton C.W., Tang Y.W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan China: the mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020;92(4):401–402. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J. China novel coronavirus I, research T. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . 2020. Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen. Accessed 14 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . 2010. Towards 100% voluntary blood donation: a global framework for action,” [internet]. Melbourne. http://www.who.int/world blood donor day/Melbourne Declaration WBDD09.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gader A.G., Osman A.M., Al Gahtani F.H., Farghali M.N., Ramadan A.H. Attitude to blood donation in Saudi Arabia. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2011;5(2):121. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.83235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shan H., Zhang P. Viral attacks on the blood supply: the impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Beijing. Transfusion. 2004;44(4):467. doi: 10.1111/j.0041-1132.2004.04401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.2020. American Association of Blood Banks. Update: impact of 2019 novel coronavirus and blood safety. Available at: http://www.aabb.org/advocacy/ regulatorygovernment/Documents/Impact-of-2019-Novel-Coronaviruson-Blood-Donation.pdf. Accessed 23 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . 2020. Important information for blood establishments regarding the novel coronavirus outbreak. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/safety-availability-biologics/importantinformation-blood-establishments-regarding-novel-coronavirusoutbreak. Accessed 23 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19) supply chain update. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-supply-chain-update. Accessed April 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gehrie E.A., Frank S.M., Goobie S.M. Balancing supply and demand for blood during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anesthesiology. 2020 doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003341. XXX:00–00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . 2003. WHO recommendations on SARS and blood safety. Available at: https:// www.who.int/csr/sars/guidelines/bloodsafety/en. Accessed 5 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang L., Yan Y., Wang L. Coronavirus disease 2019: coronaviruses and blood safety. Transfus Med Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2020.02.003. XXX:00–00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chinese Society of Blood Transfusion . 2020. Recommendations for blood establishments regarding the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) outbreak (v1.0) (English translation) Available at http://eng.csbt.org.cn/portal/article/index/id/606/cid/7.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2020. Maintaining a safe and sufficient blood supply during the 2019 coronavirus disease pandemic (COVID-19): provisional guidelines, March 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China . second edition. 2020. The laboratory biosafety guidelines for the novel coronavirus. Available at: http://stic.sz.gov.cn/xxgk/tzgg/202002/ P020200206583160300533.pdf. Accessed 23 March 2020. [In Chinese.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cancelas J.A., Dumont L.J., Maes L.A., Rugg N., Herschel L., Whitley P.H. Additive solution‐7 reduces the red blood cell cold storage lesion. Transfusion. 2015;55(3):491–498. doi: 10.1111/trf.12867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan C. Toddy for chilled platelets? Blood. 2012;119(5):1100–1102. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-394502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Red Cross email communication: March 18, 2020 from Pampee P. Young, M.D., Ph.D., Chief Medical Officer, American Red Cross.

- 21.Landro L. The Wall Street Journal; 2009. New flu victim: blood supply. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748703808904574525570410593800. Accessed 9 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. Maintaining a safe and adequate blood supply during pandemic influenza: guidelines for blood transfusion services. Available at: https://www.who.int/bloodsafety/publications/WHO_Guidelines_on_Pandemic_Influenza_and_ Blood_Supply.pdf. Accessed 9 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shander A., Goobie Sm, Warner Ma, Aapro M., Bisbe E. Essential role of patient blood management in a pandemic: a call for action. Anesth Analg. 2020 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004844. XXX:00–00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gschwender A.N., Gillard L. Disaster preparedness in the blood bank. Am Soc Clin Lab Sci. 2017;30(4):250–257. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teo D. Blood supply management during an influenza pandemic. ISBT Sci Ser. 2009;4(n2):293–298. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim K.H., Tandi T.E., Choi J.W., Moon J.M., Kim M.S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak in South Korea, 2015: epidemiology, characteristics and public health implications. J Hosp Infect. 2017;95(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadana D., Pratzer A., Scher Lj, Saag Hs, Adler N., Volpicelli Fm. Promoting high-value practice by reducing unnecessary transfusions with a patient blood management program. JAMA Internal Med. 2018;178(1):116–122. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofmann A., Farmer S., Shander A. Five drivers shifting the paradigm from product-focused transfusion practice to patient blood management. Oncologist. 2011;16(S3):3–11. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-S3-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spahn Dr, Munoz M., Klein Aa, Levy Jh, Zacharowski K. Patient blood management: effectiveness and future potential. Anesthesiology. 2020 doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003198. [published online ahead of print 24 February 2020] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frank Sm, Thakkar Rn, Podlasek Sj, Lee Kk, Wintermeyer Tl, Yang Ww. Implementing a health system–wide patient blood management program with a clinical community approach. Anesthesiology. 2017;127(5):754–764. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.2020. National Health and Health Commission, Health Bureau of the logistics support Department of the Central Military Commission. Notification on ensuring blood safety and supply during the outbreak of the novel coronavirus pneumonia. Available at: http://www.gov.cn/ zhengce/zhengceku/2020-02/11/content_5477191.htm. Accessed 21 March 2020. [In Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization . 2020. Maintaining a safe and adequate blood supply during the pandemic outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Available at: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/maintaining-a-safe-andadequate-blood-supply-during-the-pandemic-outbreak-ofcoronavirus-disease-(covid-19). Accessed 24 March 2020. [Google Scholar]