Abstract

Introduction

People living with HIV (PLWH) had a higher prevalence and incidence rate of bone fracture compared to general population. Although several studies have explored this phenomenon, the prevalence and incidence rate of fracture were varied.

Objective

The aim of the study is to determine and analyze the pooled prevalence, incidence rate of fracture and fracture risk factors among people living with HIV (PLWH).

Methods

PubMed, Cochrane Library, CINAHL with full Text, and Medline databases for studies published up to August 2019 were searched. Studies reporting the prevalence or incidence of fracture among PLWH were included. Study quality was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) appraisal tool. A meta-analysis with random-effects model was performed to determine pooled estimates of prevalence and incidence rates of fracture. A meta-regression was performed to determine the source of heterogeneity.

Results

The pooled estimated prevalence of fracture among PLWH was 6.6% (95% CI: 3.8–11.1) with pooled odds ratio of 1.9 (95%CI: 1.1–3.2) compared to the general population. The pooled estimates of fracture incidence were 11.3 per 1000 person-years (95% CI: 7.9–14.5) with incidence rate ratio (IRR) of 1.5 (95% CI: 1.3–1.8) compared to the general population. Risk factors for fracture incidence were older age (aHR 1.4, 95% CI: 1.3–1.6), smoking (aHR 1.3, 95% CI: 1.1–1.5), HIV/HCV co-infection (aHR 1.6, 95% CI: 1.3–1.9), and osteoporosis (aHR 3.3, 95% CI: 2.2–5.1).

Conclusions

Our finding highlights a higher risk of fracture among PLWH compared to the general population. Osteoporosis, smoking and HIV/HCV coinfection as the significant modifiable risk factors should be prioritized by the HIV health providers when care for PLWH.

Introduction

The success of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) over the past decades has increased the life expectancy among people living with HIV (PLWH) [1]. PLWH have increased co-morbidities, including bone fractures, which have emerged to become an important healthcare issue [2]. PLWH experience a greater risk of fractures, ranging from 1.6 to 3 times that of the general population [3]. The risk of fracture among PLWH has been associated with an increasing rate of osteoporosis due to accelerated bone loss [4, 5], bone microstructure alterations, and a reduction in bone mineral density [6]. The International Osteoporosis Foundation noted that bone fractures result in chronic pain, long-term disability, and even death [7].

A proactive approach in the prevention and treatment program is needed to minimize the consequence of bone loss and morbidity associated with fractures among PLWH [8]. Therefore, identifying the prevalence, incidence, and risk factors for fractures among PLWH is important to evaluate a prevention program. However, the current prevalence and incidence rate data are varied. Previous studies have focused on the high prevalence of osteoporosis among PLWH (15%) but not fracture risk [9]. A cohort study of PLWH identified a fracture incidence rate of 31 per 1000 person-year [10], however, a rate of 13.5 per 1000 person-year was reported in another study [3]. Arnsten’s study [10] only included older subjects (≥ 49 years), while older age was found as a risk factor for fractures among PLWH in a study by Dong et al [11].

The risk factors for fracture among PLWH remain unclear. Previous studies have been limited to select HIV populations or have included osteoporosis, not fractures, as an outcome. Earlier studies on fracture risk factors among PLWH showed a varied result. A study by Bedimo et al. found the exposure to tenofovir (TDF) regimen was the risk factors for fracture [12]. Meanwhile, Arnsten et al. found low bone mineral density (BMD) as a significant risk factor for fracture [10]

The variability of conclusive information on fracture among PLWH requires additional study. The study aimed to conduct a systematic review, and meta-regression to determine the pooled prevalence, incidence rate of fracture and fracture risk factors among PLWH.

Methods

Search strategy

Using PRISMA guidelines for a systematic review, databases were searched up to 9 August 2019 included PubMed, Cochrane Library, CINAHL with full text, and MEDLINE [13]. The terms used in the searches varied according to the database utilized, thus included HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, bone fracture, bone fragility, broken bone, osteoporosis, bone density, prevalence, incidence, risk factor, and epidemiology.

A study was eligible for inclusion if it included HIV-infected subjects aged 16 years old or above and reported fracture prevalence or incidence rate data. Cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control studies with or without a control group were included. Studies were excluded if they were not in English. Two researchers (IP, LL) independently screened all titles, abstracts, and full texts and appraised study quality. The disagreement was resolved by a third researcher (CY).

Data extraction

Data extraction included author, year of publication, study location, study design, demographics, sample size, prevalence and incidence rates of fracture, and method of fracture classification. Prevalence of fracture was expressed as a percentage of fracture among HIV positive patients from the total of HIV positive patients. Incidence was expressed as the number of fractures divided by the period of risk for all included subjects. Prevalence and incidence rate data were obtained from the studies selected. All reported cases of osteoporosis in the included studies were diagnosed by using Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA). When data was not provided, the prevalence rate was calculated by determining the number of fractures of the total HIV positive sample.

Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist tool for a prevalence study [14] The checklist consists of nine questions with four categories of answers: yes, no, unclear, and not applicable (insufficient data). “Yes” is scored as 1 and “no” is scored as 0, with a total quality score ranging from 0–9.

Data analysis

Pooled estimates used a random-effects model because of heterogeneity indicated by the I2 statistic (values of <25%, 25–75%, and >75% representing low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively) [15]. Subgroup analysis and meta-regression were performed to determine potential sources of heterogeneity. Publication bias test were performed using Egger test and Funnel plot. Statistical analysis was conducted using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software (Version 3.0 Biostat, Englewood, New Jersey, USA).

Results

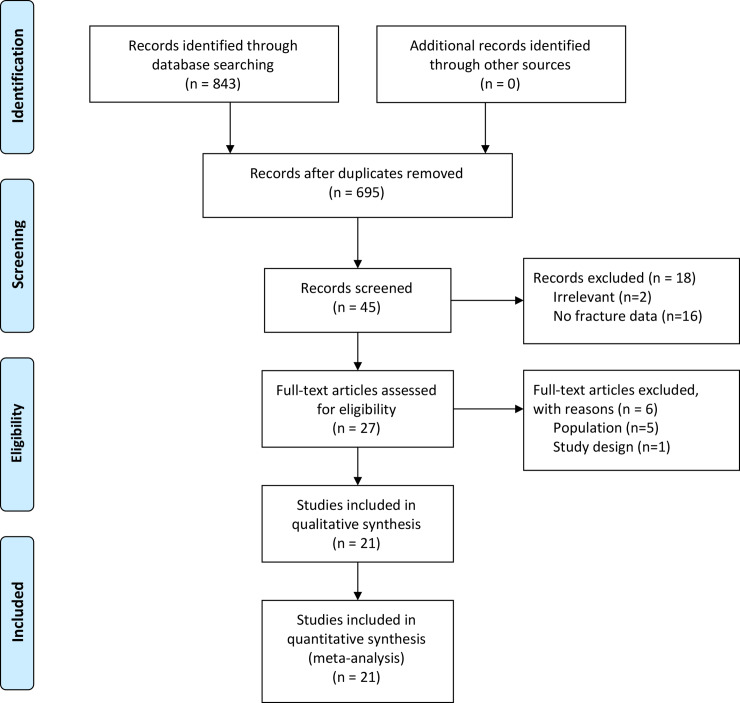

Four databases provided 843 articles from the year 2000 to February 2017 (Fig 1). After excluding duplicates, and applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 45 articles remained. After full-text examination, 21 articles remained for quality appraisal with all receiving a quality score above 7. Twelve studies received a score of 8 out of 9, and the remaining received a score of 9 out of 9 (Supporting information). Overall, the study quality was acceptable.

Fig 1. Flow diagram describing article selection according to PRISMA guidelines.

Study characteristics

Published between 2008 and 2017, all 21 studies, were conducted in developed countries. Eleven were in Europe, nine were in the United States, and the other one was a multi-countries study conducting in the European country, Israel, and Argentina (Table 1). Thirteen studies reported the prevalence and incidence data [16–28] while 8 studies reported prevalence data only [6, 29–35].

Table 1. Characteristic of studies reporting prevalence or incidence of bone fracture among PLWH (n = 21).

| Author (year) | Country | Study design | Population | Sample size (N) | Male (%) | Race (%) | Age (years) | HAART exposure (%) | Fracture ascertainment | Fracture prevalence (%) | Fracture incidence (per 1000 py) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciulini et al (2017) [6] | Italy | Cross-sectional | All HIV (+) | 141 | 87.2 | 86.5 Caucasian | 43.0, 37.0–52.0 | 93.6 | Semiquantitative/ morphometric | 13.5 | - |

| 13.5 Other | (median, IQR) | ||||||||||

| Borges et al (2017) [16] | Multi-countries | Prospective cohort | All HIV (+) | 11820 | 75.0 | 86 White | 49.0 | 96.4 | Self-report | 4.2 | 7.2 |

| 3 Asia | |||||||||||

| 5 Black | |||||||||||

| 6 Other | |||||||||||

| Battalora et al (2016) [17] | USA | Prospective cohort | All HIV(+) | 1006 | 83.2 | 67 White | 43.0, 36.0–49.0 | 96.0 | Self-report | 8.4 | 20.9 |

| 21.1 Black | (median, IQR) | ||||||||||

| 8.9 Hispanic | |||||||||||

| 3 Other | |||||||||||

| Sharma et al (2015) [18] | USA | Prospective cohort | HIV(+) women | 1713 | 0 | 24 White | 40.0, 34.0–46.0 | 63.0 | Self-report | 17.5 | 21.9 |

| 59 Black | (median, IQR) | ||||||||||

| 17 Hispanic | |||||||||||

| Gazzola et al (2015) [29] | Italy | Cross-sectional | All HIV (+) | 194 | 73.0 | 91.0 Caucasian | 49.0, 40.0–51.0 | 71.0 | Semiquantitative/ morphometric | 12.4 | |

| (median, IQR) | |||||||||||

| Byrne et al (2015) [19] | USA | Retrospective cohort | All HIV (+) | 96253 | 61.7 | 27 White | 40.9 | 100 | ICD codes | 0.8 | 2.1 |

| 56.1 Black | |||||||||||

| 21.8 Hispanic | |||||||||||

| 5.1 Other | |||||||||||

| Short et al (2014) [30] | UK | Cross-sectional | HIV (+) men | 168 | 100 | 97 Caucasian | 45.0, 38.0–51.0 | 78.0 | Self-report | 13.7 | - |

| (median, IQR) | |||||||||||

| Porcelli et al (2014) [31] | Italy | Cross-sectional | All HIV (+) | 131 | 71.0 | - | 51.0, 36.0–75.0 | - | Semiquantitative/ morphometric | 26.7 | - |

| (median, IQR) | |||||||||||

| Borderi et al (2014) [32] | Italy | Cross-sectional | All HIV (+) | 202 | 68.0 | 13.8 Caucasian | 51.0 | 86 | Semiquantitative/ morphometric | 23.3 | - |

| Peters et al (2013) [33] | UK | Cross-sectional | All HIV (+) | 222 | 60.0 | 48.0 Caucasian | 45.6, 9.3 | 85 | Self-report | 20.3 | - |

| 4 Asian | (mean, SD) | ||||||||||

| 38.0 Africa | |||||||||||

| 10 Other | |||||||||||

| Maalouf et al (2013) [20] | USA | Retrospective cohort | All HIV (+) | 56660 | 98.2 | 34.8 White | 43.5, 36.7–51.8 | 64.2 | ICD codes | 1.4 | 2.07 |

| (median, IQR) | |||||||||||

| Guerri et al (2013) [21] | Spain | Retrospective cohort | All HIV (+) | 2489 | 75.3 | - | - | ICD codes | 2.0 | 8.03 | |

| Yin et al (2012) [22] | USA | Prospective cohort | All HIV (+) | 4640 | 83.4 | 48.0 White | 39.0, 33.0–45.0 | 99.7 | Self-report | 2.3 | 4.0 |

| 28.7 Black | (median, IQR) | ||||||||||

| 20.4 Hispanic | |||||||||||

| 1.8 Asian | |||||||||||

| 1.2 Other | |||||||||||

| Torti et al (2012) [34] | Italy | Cross-sectional | HIV (+) men | 160 | 100 | - | 53.0, 42.0–71.0 | 78.1 | Semiquantitative/ morphometric | 26.9 | - |

| (median, IQR) | |||||||||||

| Lo re et al (2012) [23] | USA | Retrospective cohort | All HIV (+) | 95827 | 63.1 | 27.3 White | 39.0, 33.0–46.0 (median, IQR) | - | ICD codes | 0.8 | 1.95 |

| 44.4 Black | |||||||||||

| 8.5 Hispanic | |||||||||||

| 19.9 Other | |||||||||||

| Hansen et al (2012) [24] | Denmark | Prospective cohort | All HIV (+) | 5306 | 76.0 | 80 White | 36.7, 30.5–44.5 | 78.0 | ICD codes | 15.2 | 21.0 |

| 20 Other | (median, IQR) | ||||||||||

| Young et al (2011) [25] | USA | Prospective cohort | All HIV (+) | 5826 | 79.0 | - | 40.0, 34.0–46.0 | 73.0 | ICD codes | 4.0 | 8.9 |

| (median, IQR) | |||||||||||

| Hasse et al (2011) [26] | Swiss | Prospetive cohort | All HIV (+) | 8444 | 70.8 | - | - | 85.0 | Self-report | 1.5 | 5.5 |

| Guaraldi et al (2011) [35] | Italy | Case control | All HIV (+) | 2854 | 63.0 | - | 46.0 | - | ICD codes | 14.2 | - |

| Yin et al (2010) [27] | USA | Prospective cohort | HIV (+) women | 1728 | 0 | 13.3 White | 40.4, 8.8 | 65.6 | Self-report | 8.6 | 17.9 |

| 56.3 Black | (mean, SD) | ||||||||||

| 27.2 Latina | |||||||||||

| 3.2 Others | |||||||||||

| Triant et al (2008) [28] | USA | Prospective cohort | All HIV (+) | 8525 | 65.2 | 17.9 Black | - | - | Self-report | 2.9 | 24.9 |

| 55.1 White | |||||||||||

| 15.4 Hispanic | |||||||||||

| 11.6 Other |

PLWH = people living with HIV; HAART = highly active antiretroviral therapy; ICD = international classification of disease; py = person-years; IQR = interquartile-range; SD = standard deviation

Of the twenty-one studies reporting fracture prevalence, the sample size ranged from 131 in Porcelli et al.’s cross-sectional study in Italy [31] to 96,253 in the retrospective’ study by Byrne et al. in the United States [19] (Table 1). Ethnicity included Caucasian, Black, Hispanic, and Asian subjects. In each study the majority of subjects were men. Subject age, provided by eighteen studies, ranged from 36.7 [24] to 49 [16, 29] years. Sixteen studies provided the percentage of participants that receive highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) which ranged from 63% [18] to 100% [19]. Nine studies used self-report [16–18, 22, 26–28, 30, 33], seven studies applied ICD codes [19–21, 23–25, 35] and five studies used X-ray lateral semiquantitative method [6, 29, 31, 32, 34].

Of the thirteen studies reporting fracture incidence, nine were conducted in the United States [17–20, 22, 23, 25, 27, 28], and one each in Spain [21], Denmark [24], and Switzerland [26], with a multinational study reported from Europe [16] (Table 1). The sample size varied from 1,006 in Battalora et al.’s prospective cohort study [17] to 96,253 in a retrospective study by Byrne et al. [19]. In each study, the majority of the subjects were men. Age range and HAART exposure for fracture incidence were similar to studies reporting fracture prevalence. Seven studies used self-report [16–18, 22, 26–28] while six studies used ICD codes to ascertain fracture incidence [19–21, 23–25].

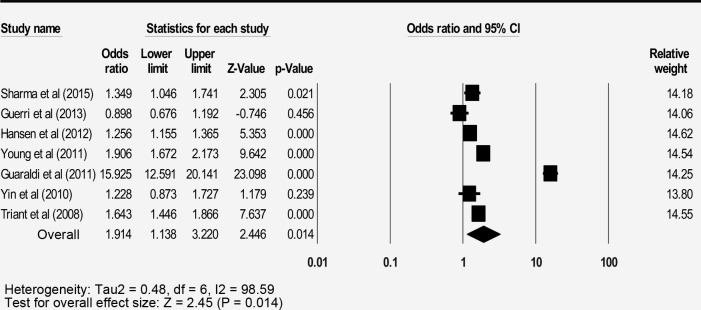

Bone fracture prevalence

The pooled prevalence of the 21 studies reporting bone fracture among people living with HIV (PLWH) was 6.6% (3.8–11.1) with a high level of heterogeneity (Table 2). The prevalence of PLWH was higher than in the general population with an odds ratio of 1.9 (95% CI: 1.1–3.2) (Fig 2). Males showed a higher prevalence compared to females (6.2% vs 4.9%, respectively). The injecting drugs users (IDUs) PLWH showed the highest prevalence of fracture (8.6%) among the risk group. PLWH who are receiving HAART showed a higher prevalence of fracture compared to those without HAART (6.7% vs 3.5%, respectively).

Table 2. Prevalence of fracture among people living with HIV by demographic variable in selected studies.

| Number of studies | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | Sample size | I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall fracture prevalence | 21 | 6.6 (3.8–11.1) | 304309 | 99.8 |

| Subgroup analysis | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 9 | 4.9 (3.2–7.4) | 9393 | 91.9 |

| Male | 9 | 6.2 (3.6–10.4) | 79632 | 99.1 |

| Age | ||||

| <41 y.o | 3 | 4.4 (1.8–10.4) | 4925 | 97.3 |

| 41–50 y.o | 3 | 5.8 (1.9–16.5) | 7455 | 99.2 |

| 51–60 y.o | 2 | 7.5 (1.8–26.5) | 2614 | 98.6 |

| >60 y.o | 2 | 7.9 (3.2–18.3) | 806 | 89.8 |

| BMI | ||||

| < 18 | 2 | 6.4 (5.1–8.2) | 990 | 0.0 |

| 18–29.9 | 3 | 6.6 (2.5–16.4) | 11089 | 98.3 |

| >29.9 | 3 | 4.7 (0.8–24.5) | 9579 | 98.7 |

| HIV risk factor | ||||

| Heterosexual | 2 | 6.2 (2.6–13.8) | 3822 | 92.4 |

| IDUs | 6 | 8.6 (4.1–17.0) | 22399 | 97.7 |

| MSM | 2 | 5.5 (2.4–12.0) | 5669 | 96.7 |

| Other risk | 2 | 4.2 (3.0–5.7) | 906 | 0.0 |

| HAART exposure | ||||

| With HAART | 5 | 6.7 (3.8–11.3) | 20727 | 98.2 |

| Without HAART | 5 | 3.5 (1.9–6.2) | 5210 | 84.9 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 5 | 3.9 (2.6–5.8) | 34858 | 97.4 |

| Black | 5 | 3.3 (2.1–5.0) | 5754 | 86.5 |

| Caucasian | 3 | 3.8 (3.2–4.4) | 4531 | 0.0 |

| Hispanic | 4 | 3.3 (1.6–6.6) | 3050 | 89.7 |

| Others | 4 | 3.0 (2.1–4.3) | 3158 | 0.0 |

| Country region | ||||

| European | 11 | 12.0 (7.0–19.7) | 20311 | 98.9 |

| America | 9 | 3.2 (1.6–6.4) | 272178 | 99.8 |

| Multi-countries | 1 | 4.2 (3.8–4.6) | 11820 | 0.0 |

| Fracture ascertainment | ||||

| ICD codes | 7 | 3.0 (1.0–8.1) | 265215 | 99.9 |

| Semi-quantitative | 5 | 20.0 (14.6–26.9) | 828 | 79.6 |

| Self-report | 9 | 6.4 (3.6–11.1) | 38266 | 99.2 |

| Study design | ||||

| Case control | 1 | 14.2 (13.0–15.5) | 2854 | 0.0 |

| Cross sectional | 7 | 19.2 (15.0–24.1) | 1218 | 75.3 |

| Retrospective cohort | 4 | 1.1 (0.8–0.9) | 251229 | 98.0 |

| Prospective cohort | 9 | 5.4 (3.0–9.5) | 49008 | 99.5 |

BMI = body mass index; IDUs = inject drugs users; MSM = male sex with male; HAART = highly active anti-retroviral therapy; CI = confidence interval ICD = international classification of disease

Fig 2. Forest plot for fracture odds ratio between PLWH and general population.

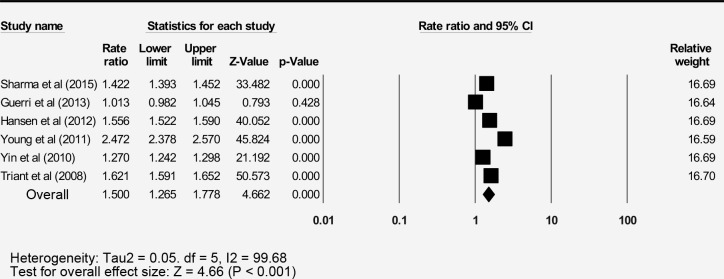

Bone fracture incidence

The pooled incidence of the 13 reports bone fracture among people living with HIV (PLWH) was 11.3 per 1000-person years (95% CI: 7.9–14.3) with a high level of heterogeneity (Table 3). The pooled rate ratio was calculated from six studies reporting fractures of the control group as 1.5 (95% CI: 1.3–1.8) (Fig 3).

Table 3. Incidence of fracture among people living with HIV by demographic variable in selected studies.

| Number of studies | Incidence (per 1000 py) (95% CI) | Sample size | I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall fracture incidence | 13 | 11.3 (7.9–14.5) | 300237 | 99.9 |

| Subgroup analysis | ||||

| Country region | ||||

| European | 3 | 11.5 (4.1–18.9) | 16239 | 99.9 |

| America | 9 | 12.0 (7.8–16.3) | 272178 | 99.9 |

| Multi-countries | 1 | 7.2 (7.0–7.4) | 11820 | 0.0 |

| Fracture ascertainment | ||||

| ICD codes | 6 | 7.3 (4.0–10.7) | 262361 | 99.9 |

| Self-report | 7 | 15.2 (6.2–12.1) | 37876 | 99.9 |

| Study design | ||||

| Retrospective cohort | 4 | 3.5 (1.7–5.4) | 251229 | 99.9 |

| Prospective cohort | 9 | 15.1 (10.0–20.2) | 49008 | 99.9 |

| Overall fracture incidence | 13 | 11.3 (7.9–14.5) | 300237 | 99.9 |

| Subgroup analysis | ||||

| Country region | ||||

| European | 3 | 11.5 (4.1–18.9) | 16239 | 99.9 |

| America | 9 | 12.0 (7.8–16.3) | 272178 | 99.9 |

| Multi-countries | 1 | 7.2 (7.0–7.4) | 11820 | 0.0 |

| Fracture ascertainment | ||||

| ICD codes | 6 | 7.3 (4.0–10.7) | 262361 | 99.9 |

| Self-report | 7 | 15.2 (6.2–12.1) | 37876 | 99.9 |

| Study design | ||||

| Retrospective cohort | 4 | 3.5 (1.7–5.4) | 251229 | 99.9 |

| Prospective cohort | 9 | 15.1 (10.0–20.2) | 49008 | 99.9 |

ICD = international classification of disease; py = person-years; CI = confidence interval

Fig 3. Forest plot for fracture incidence rate ratio between PLWH and general population.

Fracture risk factors

Traditional risk factors for fracture identified among PLWH included older age (> 60 years), smoking, and osteoporosis with adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) of 1.4, 1.3, 3.3, respectively (Table 4). HCV co-infection was an independent HIV-related risk factor with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.6 (95% CI: 1.3–1.9).

Table 4. Risk factor of fractures among people living with HIV.

| Risk factor | Sample size | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (CI 95%) | I2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older age (>60 years) | 32302 | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) | 57.73 | 0.001** |

| Female gender | 12038 | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | 0.00 | 0.258 |

| Nadir CD4 cells count | 23858 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 7.89 | 0.844 |

| Smoking | 18032 | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 66.41 | 0.010* |

| HCV coinfection | 18652 | 1.6 (1.3–1.9) | 0.00 | 0.001** |

| Lower BMI | 12826 | 1.2 (0.9–1.8) | 85.19 | 0.281 |

| Prior fracture | 12826 | 2.2 (0.7–7.1) | 87.58 | 0.168 |

| Osteoporosis | 12826 | 3.3 (2.2–5.1) | 0.00 | 0.001** |

CI = confidence interval; HCV = Hepatitis C Co-infection; BMI = body mass index

* refers to p <0.05

** refers to p < 0.005

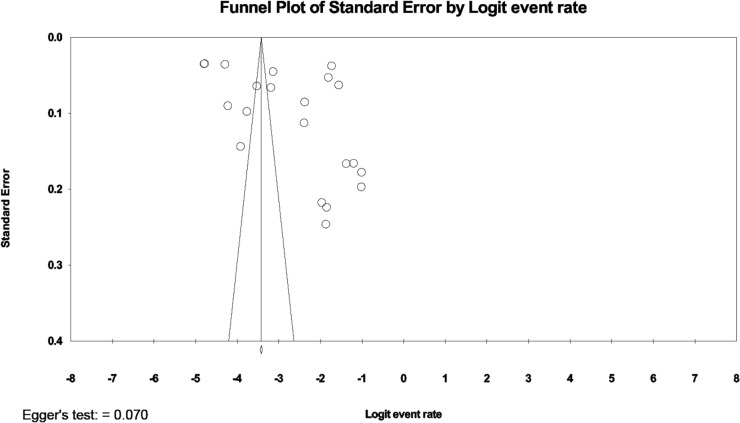

Meta-regression analysis and publication bias

A high level of heterogeneity existed across the studies reporting prevalence (I2 = 99.8%, Table 2). Univariate analysis was conducted to find significant independent covariates as a potential source of heterogeneity that could be included in a meta-regression model (Table 5). The covariates of study design (p < 0.001) and fracture identification method (p < 0.05) showed significant coefficient regression. After these covariates were included in the meta-regression analysis, only study design covariates provided a significant coefficient regression (p < 0.05). Publication bias was analyzed by generating a funnel plot and Egger’s test with neither demonstrating evidence of asymmetry (Fig 4).

Table 5. Meta-regression analysis of fracture risk factors affecting heterogeneity on prevalence a.

| Variable | Univariate coefficient (95% CI) | P value | Multivariate Coefficient (95% CI) b | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country region | ||||

| Reference: America | ||||

| Europe | 1.4 (0.5–2.3) | 0.003* | 0.1 (-0.9–0.9) | 0.994 |

| Multi-country | 0.3 (-1.9–2.5) | 0.807 | -0.2 (-1.7–1.4) | 0.836 |

| Study design | ||||

| Reference: Retrospective cohort | ||||

| Case control | 2.6 (1.1–4.2) | P < 0.001* | 2.6 (0.9–4.4) | 0.003* |

| Cross-sectional | 3.0 (2.1–3.9) | P < 0.001* | 3.4 (1.3–5.4) | 0.001* |

| Prospective cohort | 1.6 (0.7–2.4) | P < 0.001* | 2.0 (0.7–3.3) | 0.002* |

| Fracture ascertainment | ||||

| Reference: ICD codes | ||||

| Self-report | 0.8 (-0.5–2.1) | 0.217 | -0.5 (-1.7–0.7) | 0.402 |

| Semi-quantitative | 2.1 (0.6–3.6) | 0.006* | -0.3 (-2.0–1.4) | 0.722 |

* refers to statistically significant at p < 0.05

a refers to I2 statistic result (99%)

b refers to Confidence Interval

Fig 4. Funnel plot for publication bias test across studies.

Discussion

The findings of this study revealed that people living with HIV have an increased risk of bone fracture, 1.9 times higher than that observed in the general population. This finding was higher than a systematic review of HIV postmenopausal women that reported a fracture prevalence 1.5 times greater than HIV negative postmenopausal women [36]. The greater percentage of males in the studies included in the current study may explain the difference.

People living with HIV experienced an incidence rate of fracture 1.5 times that of the general population. Dong and colleagues’ meta-analysis reported a similar incidence rate ratio of fracture among PLWH of 1.8 [11]. However, the analysis only focused on subjects with HIV and HCV co-infection which may have yielded a higher incidence rate ratio. Maalouf et al. have reported a higher risk of fracture among patients with HIV/HCV co-infection compared to HIV mono-infection which was identified as a risk factor in the current study [20].

The four risk factors found significant in this meta-analysis have previously reported including older age, osteoporosis, smoking and HCV co-infection. A meta-analysis by Shiau et al. identified similar results but did not report pooled hazard ratios [37]. Older age as a traditional risk factor in this study was reported in a meta-analysis by Dong et al. who studied risks among HIV and HCV co-infected patients [11]. Osteoporosis as a risk factor for fractures showed a lower pooled adjusted hazard ratio than Short et al. [38] who reported that HIV infected men with osteoporosis had a 3.5-fold risk of fracture compared to those without osteoporosis. However, the limited population of the study may have overestimated the findings. Smoking, a significant and modifiable fracture risk factor among PLWH, is associated with a bone mineral density which is influenced by both dose and duration of smoking [39]. Wu et al. [40] reported that smokers had twice the risk of fracture compared to non-smokers. Smoking cessation programs among smokers with HIV may reduce fracture risk after just three months [41]. The HCV co-infection risk, with pooled aHR of 1.6, confirms the findings of Dong et al’s meta-analytic study. [11]. Another meta-analytic study by Shiau et al. [37] also found that HCV co-infection was an independent risk factor for both fragility and non-fragility fractures. Early intervention for HCV co-infection and PLWH, recommended by Bedimo et al. is critical to reducing bone turnover [42]

The current study adds to the literature by reporting both the prevalence and incidence rate of fractures including the HIV-related risk factor for fracture among people living with HIV. The studies included in the meta-analysis included sample sizes exceeding 1,000 and a diverse population of patients with HIV. Previous reviews focused on smaller samples with at-risk populations. Finally, a pooled adjusted Hazard Ratio of fracture risk factors provide more specific analysis than a simple summary of factors.

Limitations

The literature search excluded non-English reports as the studies all originated in developed countries, fracture risk factors of less developed countries may differ. Despite subgroup and meta-regression analysis, the synthesized literature revealed significant heterogeneity.

Conclusions

A comprehensive meta-analysis revealed a higher prevalence and incidence rate of fracture among PLWH compared to the general population. Smoking, older age, osteoporosis, and HCV coinfection are significant risk factors for fracture among PLWH.

Our finding highlights a higher risk of fracture among PLWH compared to the general population. Osteoporosis, smoking and HIV/HCV coinfection as the significant modifiable risk factors should be prioritized by the HIV health provider when managing PLWH. Further investigation of the interactions among risk factors is urgently needed to prevent bone fractures.

Supporting information

(DOC)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Ying-Ju Chang and Hsiang-Hsu for their valuable help.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) and The Directorate General of Higher Education (DIKTI) supported IP. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hileman CO, Eckard AR, McComsey GA. Bone loss in HIV: a contemporary review. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity. 2015;22(6):446–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Compston J. HIV infection and bone disease. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2016;280(4):350–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansen AB, Gerstoft J, Kronborg G, Larsen CS, Pedersen C, Pedersen G, et al. Incidence of low and high-energy fractures in persons with and without HIV infection: a Danish population-based cohort study. Aids. 2012;26(3):285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compston J. HIV infection and osteoporosis. BoneKEy Reports. 2015;4:636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzotta E, Ursini T, Agostinone A, Di Nicola AD, Polilli E, Sozio F, et al. Prevalence and predictors of low bone mineral density and fragility fractures among HIV-infected patients at one Italian center after universal DXA screening: sensitivity and specificity of current guidelines on bone mineral density management. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(4):169–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciullini L, Pennica A, Argento G, Novarini D, Teti E, Pugliese G, et al. Trabecular bone score (TBS) is associated with sub-clinical vertebral fractures in HIV-infected patients. Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism. 2017:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, et al. Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2014;25(10):2359–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Battalora LA, Young B, Overton ET. Bones, Fractures, Antiretroviral Therapy and HIV. Current infectious disease reports. 2014;16(2):393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown TT, Qaqish RB. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis: a meta-analytic review. Aids. 2006;20(17):2165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnsten JH, Freeman R, Howard AA, Floris-Moore M, Lo Y, Klein RS. Decreased bone mineral density and increased fracture risk in aging men with or at risk for HIV infection. AIDS (London, England). 2007;21(5):617–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong HV, Cortes YI, Shiau S, Yin MT. Osteoporosis and fractures in HIV/hepatitis C virus coinfection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aids. 2014;28(14):2119–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bedimo R, Maalouf NM, Zhang S, Drechsler H, Tebas P. Osteoporotic fracture risk associated with cumulative exposure to tenofovir and other antiretroviral agents. AIDS (London, England). 2012;26(7):825–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.JBI. The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews 2017. Available from: https://www.google.com.tw/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=2ahUKEwiA99K_jcndAhUX97wKHZ9iB0oQFjABegQICRAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fjoannabriggs.org%2Fassets%2Fdocs%2Fcritical-appraisal-tools%2FJBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Prevalence_Studies2017.docx&usg=AOvVaw0sBBiTXFHZzidLLsRrMt6F.

- 15.Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods. 2006;11(2):193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borges AH, Hoy J, Florence E, Sedlacek D, Stellbrink H-J, Uzdaviniene V, et al. Antiretrovirals, Fractures, and Osteonecrosis in a Large International HIV Cohort. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2017;64(10):1413–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Battalora L, Buchacz K, Armon C, Overton ET, Hammer J, Patel P, et al. Low bone mineral density and risk of incident fracture in HIV-infected adults. Antiviral therapy. 2016;21(1):45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma A, Shi Q, Hoover DR, Anastos K, Tien PC, Young MA, et al. Increased Fracture Incidence in Middle-Aged HIV-Infected and HIV-Uninfected Women: Updated Results From the Women's Interagency HIV Study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2015;70(1):54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrne DD, Newcomb CW, Carbonari DM, Nezamzadeh MS, Leidl KB, Herlim M, et al. Increased risk of hip fracture associated with dually treated HIV/hepatitis B virus coinfection. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22(11):936–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maalouf NM, Zhang S, Drechsler H, Brown GR, Tebas P, Bedimo R. Hepatitis C co-infection and severity of liver disease as risk factors for osteoporotic fractures among HIV-infected patients. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2013;28(12):2577–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guerri-Fernandez R, Vestergaard P, Carbonell C, Knobel H, Aviles FF, Castro AS, et al. HIV infection is strongly associated with hip fracture risk, independently of age, gender, and comorbidities: a population-based cohort study. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2013;28(6):1259–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin MT, Kendall MA, Wu X, Tassiopoulos K, Hochberg M, Huang JS, et al. Fractures after antiretroviral initiation. AIDS (London, England). 2012;26(17):2175–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo Re V 3rd, Volk J, Newcomb CW, Yang Y-X, Freeman CP, Hennessy S, et al. Risk of hip fracture associated with hepatitis C virus infection and hepatitis C/human immunodeficiency virus coinfection. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md). 2012;56(5):1688–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen A-BE, Gerstoft J, Kronborg G, Larsen CS, Pedersen C, Pedersen G, et al. Incidence of low and high-energy fractures in persons with and without HIV infection: a Danish population-based cohort study. AIDS (London, England). 2012;26(3):285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young B, Dao CN, Buchacz K, Baker R, Brooks JT. Increased rates of bone fracture among HIV-infected persons in the HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS) compared with the US general population, 2000–2006. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011;52(8):1061–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Furrer H, Battegay M, Hirschel B, Cavassini M, et al. Morbidity and aging in HIV-infected persons: the Swiss HIV cohort study. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011;53(11):1130–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin MT, Shi Q, Hoover DR, Anastos K, Sharma A, Young M, et al. Fracture incidence in HIV-infected women: results from the Women's Interagency HIV Study. AIDS (London, England). 2010;24(17):2679–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Triant VA, Brown TT, Lee H, Grinspoon SK. Fracture prevalence among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected versus non-HIV-infected patients in a large U.S. healthcare system. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2008;93(9):3499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gazzola L, Savoldi A, Bai F, Magenta A, Dziubak M, Pietrogrande L, et al. Assessment of radiological vertebral fractures in HIV-infected patients: clinical implications and predictive factors. HIV Med. 2015;16(9):563–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Short C-ES, Shaw SG, Fisher MJ, Walker-Bone K, Gilleece YC. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Osteoporosis and Fracture among a Male HIV-Infected Population in the UK. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2014;25(2):113–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porcelli T, Gotti D, Cristiano A, Maffezzoni F, Mazziotti G, Foca E, et al. Role of bone mineral density in predicting morphometric vertebral fractures in patients with HIV infection. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2014;25(9):2263–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borderi M, Calza L, Colangeli V, Vanino E, Viale P, Gibellini D, et al. Prevalence of sub-clinical vertebral fractures in HIV-infected patients. The new microbiologica. 2014;37(1):25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peters BS, Perry M, Wierzbicki AS, Wolber LE, Blake GM, Patel N, et al. A cross-sectional randomised study of fracture risk in people with HIV infection in the probono 1 study. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e78048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torti C, Mazziotti G, Soldini PA, Foca E, Maroldi R, Gotti D, et al. High prevalence of radiological vertebral fractures in HIV-infected males. Endocrine. 2012;41(3):512–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guaraldi G, Orlando G, Zona S, Menozzi M, Carli F, Garlassi E, et al. Premature age-related comorbidities among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011;53(11):1120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cortes YI, Yin MT, Reame NK. Bone Density and Fractures in HIV-infected Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2015;26(4):387–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiau S, Broun EC, Arpadi SM, Yin MT. Incident fractures in HIV-infected individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aids. 2013;27(12):1949–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Short, Shaw SG, Fisher MJ, Walker-Bone K, Gilleece YC. Prevalence of and risk factors for osteoporosis and fracture among a male HIV-infected population in the UK. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2014;25(2):113–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubinstein ML, Harris DR, Rudy BJ, Kapogiannis BG, Aldrovandi GM, Mulligan K. Exploration of the Effect of Tobacco Smoking on Metabolic Measures in Young People Living with HIV. AIDS Res Treat. 2014;2014:740545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu Z-J, Zhao P, Liu B, Yuan Z-C. Effect of Cigarette Smoking on Risk of Hip Fracture in Men: A Meta-Analysis of 14 Prospective Cohort Studies. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(12):e0168990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vidrine DJ, Frank SG, Savin MJ, Waters AJ, Li Y, Chen S, et al. HIV Care Initiation: A Teachable Moment for Smoking Cessation? Nicotine Tob Res. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bedimo R, Maalouf NM, Lo Re V 3rd. Hepatitis C virus coinfection as a risk factor for osteoporosis and fracture. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2016;11(3):285–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.