Summary

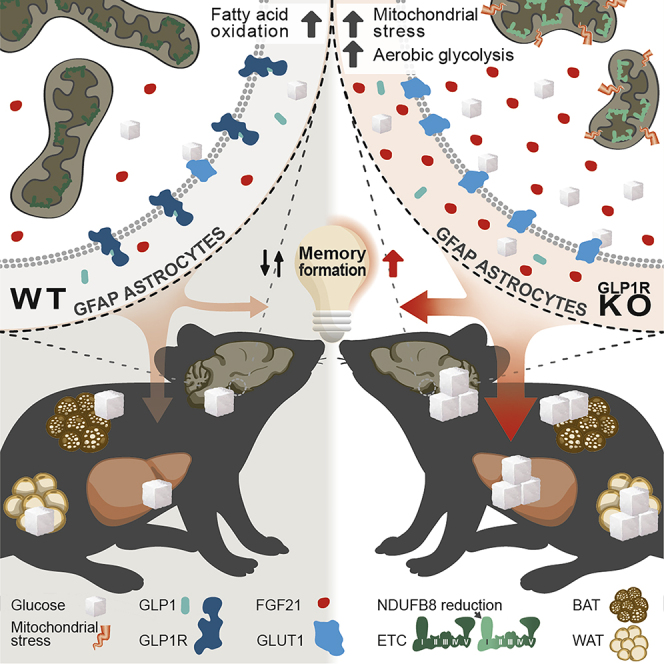

Astrocytes represent central regulators of brain glucose metabolism and neuronal function. They have recently been shown to adapt their function in response to alterations in nutritional state through responding to the energy state-sensing hormones leptin and insulin. Here, we demonstrate that glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 inhibits glucose uptake and promotes β-oxidation in cultured astrocytes. Conversely, postnatal GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) deletion in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-expressing astrocytes impairs astrocyte mitochondrial integrity and activates an integrated stress response with enhanced fibroblast growth factor (FGF)21 production and increased brain glucose uptake. Accordingly, central neutralization of FGF21 or astrocyte-specific FGF21 inactivation abrogates the improvements in glucose tolerance and learning in mice lacking GLP-1R expression in astrocytes. Collectively, these experiments reveal a role for astrocyte GLP-1R signaling in maintaining mitochondrial integrity, and lack of GLP-1R signaling mounts an adaptive stress response resulting in an improvement of systemic glucose homeostasis and memory formation.

Keywords: GLP-1, astrocytes, mitochondria, ß-oxidation, stress response, FGF-21, glucose metabolism, obesity, energy homeostasis, hepatic glucose production

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

GLP-1 inhibits glucose uptake and promotes β-oxidation in cultured astrocytes

-

•

Lack of astrocyte GLP-1R in vivo activates a stress response and increases FGF21

-

•

Adaptations to astrocyte GLP-1R deletion improve glucose metabolism and memory

Astrocytes regulate brain glucose metabolism and neuronal function. Timper et al. describe a role for astrocyte GLP-1R signaling in maintaining mitochondrial integrity and demonstrate that lack of astrocyte GLP-1R signaling mounts an adaptive stress response to increase astrocyte FGF21 expression resulting in an improvement of systemic glucose homeostasis and memory formation.

Context and Significance

Astrocytes represent central regulators of brain glucose metabolism and neuronal function. In this study, researchers at Max Planck Institute and their collaborators discovered that astrocytes within different brain regions express the receptor for GLP-1, a hormone known to regulate systemic glycemia and food intake. They uncovered that GLP-1 inhibits glucose uptake and promotes the utilization of fatty acids in astrocytes and demonstrated a role for astrocyte GLP-1R signaling in maintaining mitochondrial integrity. Lack of GLP-1R signaling in astrocytes mounts an adaptive stress response resulting in an improvement of systemic glucose homeostasis and memory formation. These results reveal a novel role for GLP-1 in controlling fuel utilization in astrocytes, a process with potential implications for the regulation of neuronal function and neurodegeneration.

Introduction

Extensive research over the last decades uncovered distinct neuronal populations within the hypothalamus as master regulators of systemic energy metabolism, integrating information about the nutritional status of the organism into a coordinated feedback response on food intake, glucose homeostasis, and energy expenditure (Timper and Brüning, 2017). However, recent studies unraveled that astrocytes, the most abundant cell type in the adult brain (Freeman, 2010), play a major role in the central control of glucose and energy metabolism (Gao et al., 2017, García-Cáceres et al., 2016, Kim et al., 2014, Vicente-Gutierrez et al., 2019, Yang et al., 2015, Zhang et al., 2017). Here, astrocytes not only regulate systemic glucose and energy homeostasis in response to leptin (Kim et al., 2014) and insulin (García-Cáceres et al., 2016) but also modulate brain metabolism via control of glucose transport (García-Cáceres et al., 2016) to adapt behavioral responses (Vicente-Gutierrez et al., 2019).

Interestingly, astrocytes also express the glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 receptor (GLP-1R) (Alvarez et al., 1996, Chowen et al., 1999, Yun et al., 2018). GLP-1, derived from the proglucagon gene, has originally been identified as an incretin hormone released from enteroendocrine L-cells upon nutrient ingestion. In pancreatic islets, GLP-1 promotes glucose-dependent insulin secretion while inhibiting glucagon release, making it an attractive target for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (Drucker, 2018). As circulating endogenous GLP-1 has a half-life of only several minutes (Gutniak et al., 1994), multiple long-acting GLP-1R agonists have been developed, which are widely used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (Drucker, 2018, Knudsen et al., 2007). In addition to their glucoregulatory effects, GLP-1R agonists promote satiety and reduce food intake both in rodents and humans (Drucker, 2018) and thus entered clinical routine for the treatment of obesity. Furthermore, numerous preclinical studies point toward a broad neuroprotective effect of GLP-1R agonists in rodent models (Yun et al., 2018) with already promising therapeutic efficacy in recent clinical trials in patients with Parkinson’s (Athauda et al., 2017, Aviles-Olmos et al., 2013) and Alzheimer’s disease (Gejl et al., 2016).

Importantly, GLP-1 is also produced by distinct proglucagon-expressing neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) of the hindbrain, which project to various brain regions, including the hypothalamus (Secher et al., 2014). Within the central nervous system (CNS), endogenous GLP-1 acts as a modulator of food intake and body weight as revealed by hypothalamus-specific deletion of the GLP-1R (Liu et al., 2017, López-Ferreras et al., 2018). Recent work has highlighted the marked differences between action of endogenous GLP-1 and effects of exogenously applied GLP-1R agonists: while systemically administered GLP-1R agonists induce weight loss in the absence of GLP-1R expression in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) (Burmeister et al., 2017, Secher et al., 2014), the anorexigenic effects of endogenous GLP-1 were abolished upon PVH-specific GLP-1R deletion (Liu et al., 2017). Overall, the exact cellular target(s) mediating the neuronal metabolic effects of central GLP-1 and GLP-1R agonists remain to be fully elucidated. More recently, it was shown that the anorexia-inducing effect of a GLP-1R agonist in the hindbrain is, at least in part, mediated via astrocytes (Reiner et al., 2016). Given the emerging importance of astrocytes in central energy metabolism control, we aimed at investigating the role of endogenous GLP-1R signaling in astrocytes in the regulation of brain and systemic energy and glucose homeostasis.

Results

GLP-1 Promotes β-Oxidation in Cultured Hypothalamic Astrocytes

In an attempt to investigate the potential role of GLP-1 action in astrocytes, we first assessed the expression of the GLP-1R in astrocytes via RNAscope-based in situ hybridization as well as via assessment of uptake of the fluorescently labeled GLP-1R agonist liraglutide (liraglutide594) in distinct brain areas in C57Bl6/N control mice as well as in mice lacking the GLP-1R (GLP-1RΔ/Δ mice) (Scrocchi et al., 1996). This analysis revealed astrocyte GLP-1R expression in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARH), the PVH, the hippocampus, and the NTS in control mice, but not in GLP-1RΔ/Δ mice (Figures S1A and S1B), while there was no astrocyte GLP-1R expression detectable in the nucleus accumbens (Acc) in control and GLP-1RΔ/Δ mice (Figures S1A and S1B).

Having validated the expression of the GLP1-R in astrocytes, we studied the effects of GLP-1R activation in cultured hypothalamic astrocytes. Here, we assessed alterations of GLP-1R expression in primary astrocytes isolated from C57Bl6/N wild-type mice upon incubation at 25 or 2 mM glucose, revealing increased GLP-1R expression in astrocytes under low- versus high-glucose conditions (Figure S2A).

We next investigated if GLP-1 treatment potentially alters glucose uptake in primary hypothalamic astrocytes. Treatment of glucose-starved hypothalamic astrocytes with 100 nM GLP-1 for 30 min led to a reduction in subsequent glucose uptake (Figure S2B). We then studied how the acute decrease in glucose uptake upon GLP-1 treatment impacts astrocyte cellular metabolism and mitochondrial respiration. To this end, we treated glucose-deprived primary astrocytes with 100 nM GLP-1 in the presence or absence of etomoxir, an inhibitor of mitochondrial fatty acid uptake and thus subsequent oxidation (Samudio et al., 2010, Wicks et al., 2015), and assessed mitochondrial respiration in the presence of glucose. While GLP-1 treatment affected neither basal nor maximal mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate (OCR) or ATP production in the absence of etomoxir, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) was reduced upon GLP-1 treatment when fatty acid oxidation was inhibited by etomoxir (Figures S2C and S2D). Of note, etomoxir alone did not alter astrocyte mitochondrial respiration in the presence of glucose (Figures S2C and S2D). The observation that mitochondrial respiration was impaired upon GLP-1 in the presence, but not in the absence, of etomoxir led us to hypothesize that GLP-1 might induce fatty acid oxidation at the expense of reduced glucose utilization. Therefore, we assessed astrocyte fatty acid oxidation in glucose-deprived primary hypothalamic astrocytes upon acute GLP-1 treatment. Indeed, exogenous fatty acid oxidation in the presence of palmitate (Figures S2E and S2F) and endogenous fatty acid oxidation in the presence of BSA (Figures S2G and S2H) were enhanced upon acute GLP-1 treatment.

Next, we aimed to determine whether the observed effects of GLP-1 depended on astrocyte-autonomous GLP-1R signaling. To this end, primary astrocytes from the hypothalamus of 1- to 3-day-old GLP-1Rflox/flox pups were isolated and cultured as previously described (García-Cáceres et al., 2016) (Figure S3A). GLP-1R deletion in primary hypothalamic astrocytes was induced by incubating cells with an AAV expressing either Cre or GFP as a control (García-Cáceres et al., 2016), resulting in successful reduction of GLP-1R protein (Figure S3B) and mRNA (Figure S3C) expression upon Cre-mediated deletion. Comparing control and GLP-1R-deficient astrocytes showed that the effects of GLP-1 on mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation were impaired in GLP-1R-deficient (Figures S3E and S3F) compared to control astrocytes (Figures S3D and S3F).

GLP-1R Ablation in Hypothalamic Astrocytes Impairs Mitochondrial Function

Given the critical role of mitochondria in substrate utilization of astrocytes, we decided to investigate the dependence of cultured hypothalamic astrocytes on functional endogenous GLP-1R expression. Here, we compared mitochondrial respiration in control and GLP-1R-deficient hypothalamic astrocytes. Real-time measurement of mitochondrial OCR revealed a slight impairment in basal and maximal mitochondrial respiration as well as in mitochondrial ATP production in hypothalamic astrocytes upon GLP-1R deletion (Figures 1A and 1B). We therefore analyzed the protein expression of subunits of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes in these cells. GLP-1R deletion was associated with a slight reduction in protein expression of the complex I subunit NDUFB8, while other mitochondrial complexes, including the complex I subunit NDUFA9, were not altered (Figures 1C and 1D). Of note, mitochondrial mass was not changed in primary astrocytes upon GLP-1R deletion (Figure 1E). NDUFB8 deficiency results in mitochondrial complex I dysfunction (Piekutowska-Abramczuk et al., 2018). As complex I dysfunction is associated with compensatory increased glucose uptake (Liemburg-Apers et al., 2016), we next investigated if GLR-1R deletion affects glucose handling in primary hypothalamic astrocytes ex vivo. Indeed, glucose uptake was enhanced in primary hypothalamic astrocytes with GLP-1R deficiency compared to control astrocytes (Figure 1F). Glucose uptake in astrocytes is mainly mediated via glucose transporter (GLUT)-1 (García-Cáceres et al., 2016, Simpson et al., 1999). Therefore, we investigated if the increase in glucose uptake upon GLP-1R ablation in primary astrocytes might involve altered GLUT-1 regulation. Glucose-starved GLP-1R-deficient astrocytes showed increased levels of phosphorylated Ser-226 on GLUT-1 (Figure 1G), which has been shown to enhance GLUT-1-mediated glucose uptake (Lee et al., 2015). In line, enhanced glucose uptake in GLP-1R-deficient astrocytes was prevented upon pre-incubation with the GLUT-1 inhibitor WBZ117 (Figure 1H).

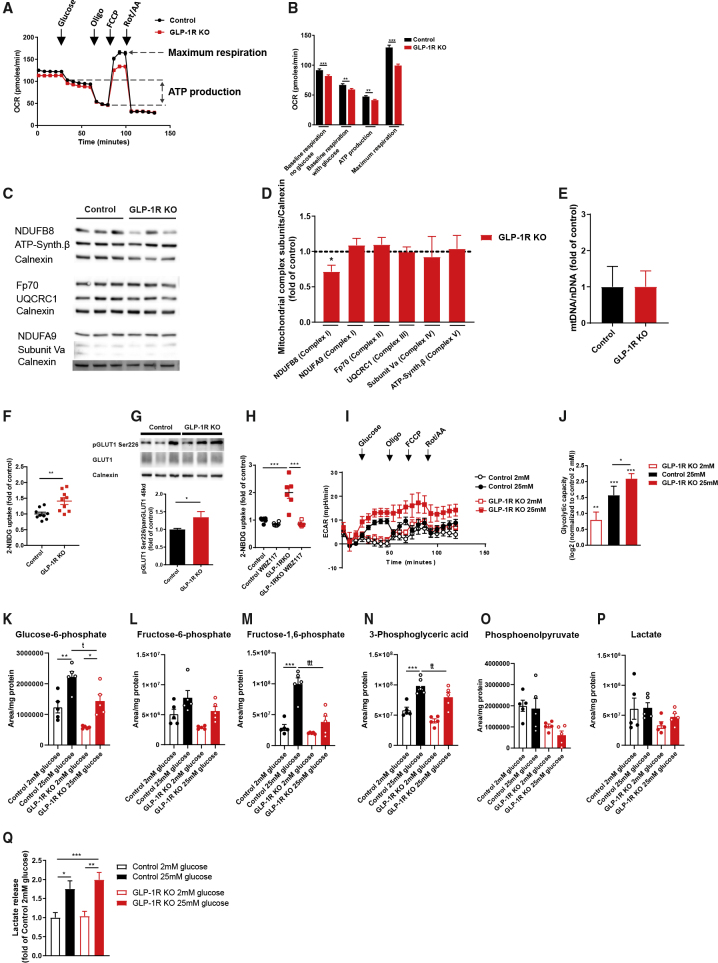

Figure 1.

GLP-1R Ablation in Hypothalamic Astrocytes Alters Mitochondrial Function Associated with Increased Glucose Uptake and Glycolytic Flux

(A and B) Representative analysis (A) and quantification (B) of baseline oxygen consumption rate (OCR) before (no gluc) and after glucose (with gluc) administration. ATP-linked and maximum respiration OCR in GLP-1R-deficient (GLP-1R KO) and control hypothalamic astrocytes (representative experiment from n = 8 independently isolated astrocyte cultures).

(C and D) Western blot analysis (C) and quantification of expression (D) of respiratory chain subunits in GLP-1R KO and control hypothalamic astrocytes (n = 4 independently isolated astrocyte cultures).

(E) Mitochondrial content in GLP-1R KO and control hypothalamic astrocytes (ratio of mitochondrial DNA to nuclear DNA [mtDNA/nDNA]) (n = 3 independently isolated astrocyte cultures).

(F) Glucose uptake in GLP-1R KO and control hypothalamic astrocytes (n = 9 independently isolated astrocyte cultures).

(G) Representative immunoblots of Ser-226 GLUT-1 phosphorylation in GLP-1R KO and control hypothalamic astrocytes. Quantification of pSer226-GLUT1 levels was performed after normalization to total GLUT1 and calnexin as loading control (n = 12 independently isolated astrocyte cultures).

(H) Glucose uptake in the presence or absence of the GLUT-1 inhibitor WBZ117 in GLP-1R KO and control hypothalamic astrocytes (n = 6 independently isolated astrocyte cultures).

(I) Representative glycolytic flux analysis in GLP-1R KO and control hypothalamic astrocytes upon incubation with 2 or 25 mM glucose.

(J) Log2-transfomed proportional values and quantification of glycolytic capacity normalized to control 2 mM glucose as described in (I) from n = 4 independently isolated astrocyte cultures.

(K–P) Cellular glycolytic metabolites in GLP-1R KO and control hypothalamic astrocytes upon administration of 2 or 25 mM glucose for 1 h (n = 5 independently isolated astrocyte cultures).

(Q) Lactate secretion of GLP-1R KO and control hypothalamic astrocytes upon administration of 2 or 25 mM glucose for 1 h (n = 15 independently isolated astrocyte cultures).

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001 as determined by unpaired Mann-Whitney test (D), two-tailed Student’s t test (B, F, and G), and two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test (H and J–Q). See also Figures S1–S4.

Next, we intended to elucidate how the increase in glucose uptake impacts cellular energy metabolism upon GLP-1R deletion in hypothalamic astrocytes. Exposure of primary hypothalamic astrocytes to low and high glucose concentrations revealed that glycolytic capacity, as measured by extracellular acidification rate (ECAR), was increased in GLP-1R-deficient astrocytes in the presence of both low and high glucose (Figures 1I and 1J), in line with an increased glucose uptake fueling aerobic glycolysis to apparently compensate for the slight reduction in OXPHOS (Hou et al., 2018, Rafikov et al., 2015, Supplie et al., 2017). Accordingly, metabolic profiling revealed reduced intracellular concentrations of glycolytic metabolites (Figures 1K–1P) but an unaltered lactate secretion of GLP-1R-deficient compared to control astrocytes (Figure 1Q), overall indicating a higher glycolytic flux in astrocytes lacking GLP-1R expression.

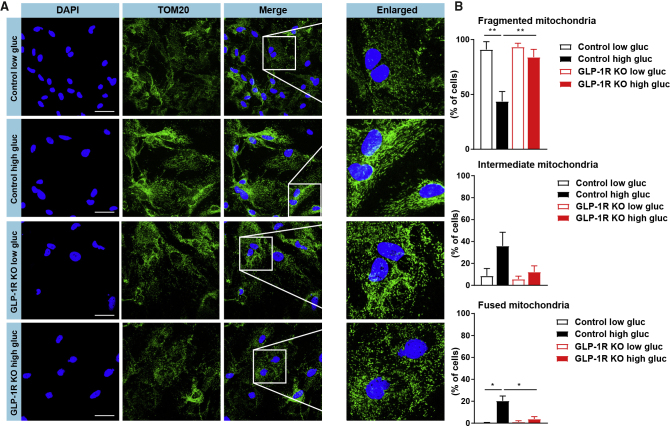

Mitochondria adapt to changes in energy state and nutrient supply by morphological changes such as fusion and fission (Wai and Langer, 2016). Accordingly, acute systemic glucose loading induces changes in mitochondrial morphology in neurons (Nasrallah and Horvath, 2014) and astrocytes (García-Cáceres et al., 2016) within the ARH. To assess astrocyte mitochondrial dynamics upon glucose exposure ex vivo, GLP-1R-deficient and control hypothalamic astrocytes were incubated at low glucose concentrations and then exposed to either low or high glucose concentrations before assessing mitochondrial morphology via TOM20 immunostaining (Figure 2A). These experiments revealed that ex vivo acute glucose exposure induced mitochondrial elongation in glucose-deprived control astrocytes, while these changes in mitochondrial morphology were absent in astrocytes lacking GLP-1Rs (Figure 2B). In summary, GLP-1R deficiency alters mitochondrial adaptations to an acute glucose challenge in hypothalamic astrocyte ex vivo.

Figure 2.

Reduction of GLP-1R Expression Alters Mitochondrial Integrity in Hypothalamic Astrocytes

(A) Representative confocal images of immunocytochemistry detection of TOM20 (green) and nuclear counterstaining (DAPI, blue) in cultured GLP-1R-deficient (GLP-1R KO) and control primary hypothalamic mouse astrocytes in response to a 20 min incubation with low glucose (2 mM glucose) or high glucose (25 mM glucose) after incubation at 2 mM glucose. Scale bars, 50 μm.

(B) Quantification of mitochondrial morphology in GLP-1R KO and control primary hypothalamic mouse astrocytes upon treatment conditions as described in (A) (n = 3 independently isolated astrocyte cultures).

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01 as determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test.

Mitochondrial dysfunction in general and in particular upon reduction of NDUFB8 expression is associated with the activation of an integrated stress response resulting in increased expression and release of FGF21 in various cell types (Agnew et al., 2018, Gómez-Sámano et al., 2017, Pereira et al., 2017, Restelli et al., 2018). Interestingly, FGF21 is also expressed in cultured glia cells (Mäkelä et al., 2014). Indeed, GLP-1R deficiency resulted in increased expression of activating transcription factor (ATF) 4, a key regulator of the integrated stress response upon mitochondrial dysfunction (Kim et al., 2013) (Figure S4A). Regarding other ATF4-induced stress response genes, only ATF5 was upregulated, while expression of CHOP, Bip, or PPARα was not altered in GLP-1R-deficient astrocytes (Figure S4A). Moreover, FGF21 expression was slightly increased in primary hypothalamic astrocytes upon GLP-1R ablation (Figure S4B). In summary, GLP-1R deletion in primary astrocytes is associated with a mild impairment in mitochondrial function in the presence of reduced NDUFB8 expression, which promotes a compensatory increase in GLUT-1-mediated glucose uptake, aerobic glycolysis, and an increase in FGF21 expression.

Generation of a Mouse Model with Inducible Astrocyte-Specific GLP-1R Deletion

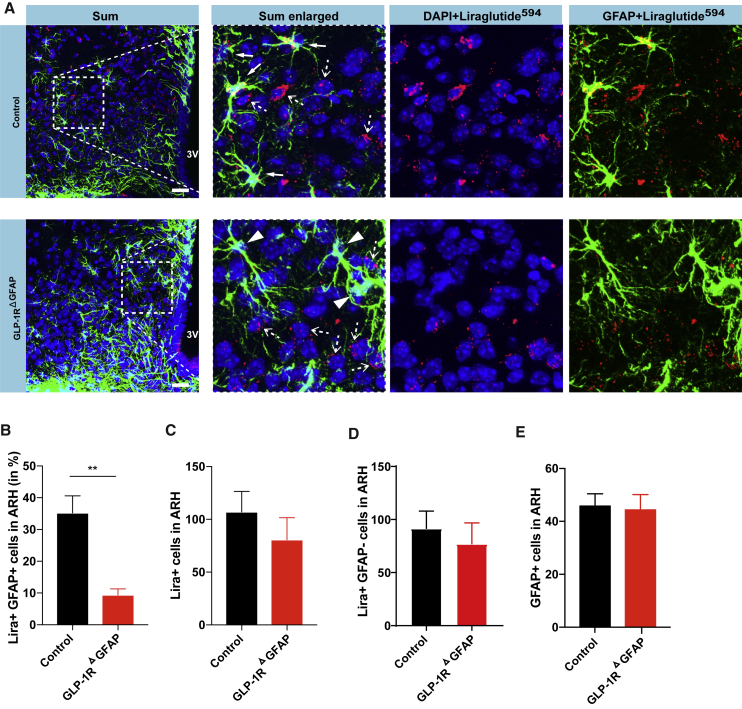

To study the role of GLP-1R signaling in astrocytes in vivo, we generated mice allowing for ablation of GLP-1R expression in astrocytes in a time-controlled manner in adult mice. To this end, we crossed mice expressing the tamoxifen-sensible fusion protein of a mutant ligand-binding domain of the estrogen receptor with the Cre recombinase (CreERT2) under the control of the human glial fibrillary acidic protein (hGFAP) promotor (Ganat et al., 2006) to mice carrying a loxP flanked human GLP-1R in the mouse GLP-1R locus (Jun et al., 2014). Tamoxifen application allowed for postnatal deletion of the GLP-1R in GFAP-expressing astrocytes (GLP-1RΔGFAP mice). Functional GLP-1R expression in astrocytes in the ARH of control mice and GLP-1R deletion in GLP-1RΔGFAP mice were investigated upon intraperitoneal injection with fluorescently labeled liraglutide594 (Secher et al., 2014) (Figure 3A). While uptake of liraglutide594 was detectable in GFAP-expressing astrocytes in the ARH of control mice, in GLP-1RΔGFAP mice liraglutide594 uptake was reduced in GFAP-expressing astrocytes (Figure 3A). Accordingly, the percentage of liraglutide594-positive GFAP astrocytes was reduced in GLP-1RΔGFAP compared to control mice (Figure 3B), while there was no difference in the number of all liraglutide594-labeled (Figure 3C) and liraglutide594-labeled, GFAP-negative ARH cells (Figure 3D) between the genotypes. Furthermore, numbers of GFAP-expressing astrocytes did not differ between GLP-1RΔGFAP and control mice (Figure 3E). These results further supported that the GLP-1R is expressed in hypothalamic astrocytes as well as successful Cre-dependent reduction of GLP-1R expression in GFAP-positive hypothalamic astrocytes in our mouse model in vivo.

Figure 3.

Generation of a Mouse Model with Inducible Astrocyte-Specific GLP-1R Deletion

Representative confocal images (A) and quantification (B–E) of immunohistochemistry detection of liraglutide594 uptake (red), GFAP (green), and corresponding nuclear counterstaining (DAPI, blue) in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARH) of GLP-1RΔGFAP and control mice (n = 4 mice per genotype). Filled arrows, liraglutide594-positive, GFAP-double-positive cells; dotted arrows, liraglutide594-positive, GFAP-negative cells; arrowheads, liraglutide594-negative, GFAP-positive cells. 3V, third ventricle, Scale bars, 100 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of (B) the percentage of liraglutide594-positive, GFAP-positive astrocytes; (C) the average number of all liraglutide594-positive cells; (D) the average number of all liraglutide594-positive, GFAP-negative cells; and (E) all GFAP-positive cells per hemi-ARH. ∗∗p ≤ 0.01 as determined by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (B–E).

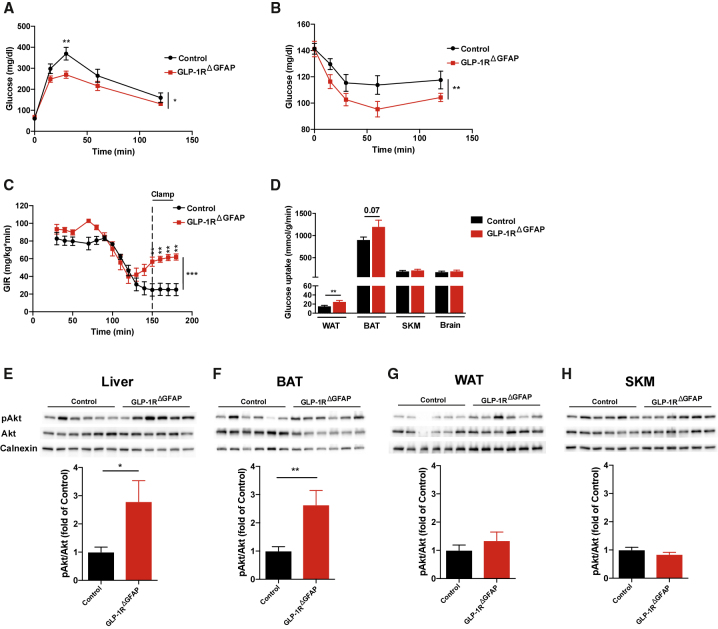

Deficient Astrocyte GLP-1R Signaling Improves Systemic Glucose Homeostasis

We then investigated whether mice with reduced GLP-1R expression in astrocytes display alterations in systemic glucose handling and energy homeostasis. To this end, we performed glucose tolerance tests, revealing an improved ability to clear a peripheral glucose load in mice with astrocyte-specific GLP-1R deficiency compared to control mice (Figure 4A). This occurred in the absence of differences in insulin secretion (Figure S5A), fasting blood glucose levels (Figure S5B), and central or peripheral GLP-1 levels between GLP-1RΔGFAP and control mice (Figure S5C). Rather, improved glucose tolerance appears to result from enhanced hepatic glucose clearance (Ros et al., 2010) as indicated by increased liver glycogen content in GLP-1RΔGFAP mice (Figure S5D). Furthermore, mice with astrocyte-specific GLP-1R deficiency displayed improved insulin sensitivity as revealed by insulin tolerance tests (Figure 4B). In support of this finding, during hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp studies, greater glucose infusion rates were needed during the steady state of the experiment (Figure 4C) to achieve similar glucose values in GLP-1RΔGFAP compared to control mice (Figure S5E). Moreover, assessment of tissue-specific glucose uptake rates revealed enhanced glucose uptake in white adipose tissue (WAT) and a tendency toward increased glucose uptake in brown adipose tissue (BAT), while no difference was observed in skeletal muscle (SKM) or in the brain of GLP-1RΔGFAP mice (Figure 4D). In support of enhanced hepatic insulin sensitivity, insulin-dependent suppression of hepatic glucose production (HGP) was improved in mice lacking GLP-1R in astrocytes compared to littermate controls (Figure S5F), while there was no difference in steady-state serum insulin levels between the genotypes (Figure S5G). Nevertheless, these results cannot be fully interpreted in the presence of negative HGP values. However, analysis of hepatic insulin signaling, via assessing hepatic pAkt levels in post-clamp liver samples, also showed an increase in insulin-stimulated Akt signaling in these mice (Figure 4E). Insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation was also enhanced in BAT (Figure 4F), but not in WAT (Figure 4G) or SKM (Figure 4H), of GLP-1RΔGFAP mice. Of note, improvements in glucose metabolism were not due to differences in body weight (Figure S5H) or body composition (Figure S5I), nor did we observe differences in fasting plasma leptin levels (Figure S5J) or organ weights (Figure S5K) between the mice of different genotypes. Accordingly, food intake (Figure S5L), fluid intake (Figure S5M), energy expenditure (EE) (Figure S5N), and locomotor activity (Figure S5O) were not altered in GLP-1RΔGFAP mice compared to control mice.

Figure 4.

Impaired Astrocyte GLP-1R Signaling Improves Systemic Glucose Homeostasis

(A and B) Glucose tolerance test (A) and insulin tolerance test (B) in GLP-1RΔGFAP and control mice (n = 10–12 per genotype).

(C and D) Glucose infusion rate (GIR) (C) and organ-specific glucose uptake rates (D) in perigonadal white adipose tissue (WAT), brown adipose tissue (BAT), skeletal muscle (SKM), and brain during hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp studies (n = 9–10 per genotype).

(E–H) Representative immunoblots showing phosphorylation of AKT (p-AKT) determined in clamped (E) liver, (F) BAT, (G) WAT, and (H) SKM samples of GLP-1RΔGFAP and control mice (n = 9–10 per genotype). Quantification of p-AKT levels was performed after normalization to total AKT and calnexin as loading control.

Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001 as determined by two-way ANOVA with repeated-measurements (time) followed by Bonferroni post hoc test (A–C) and two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (D–H). See also Figure S5.

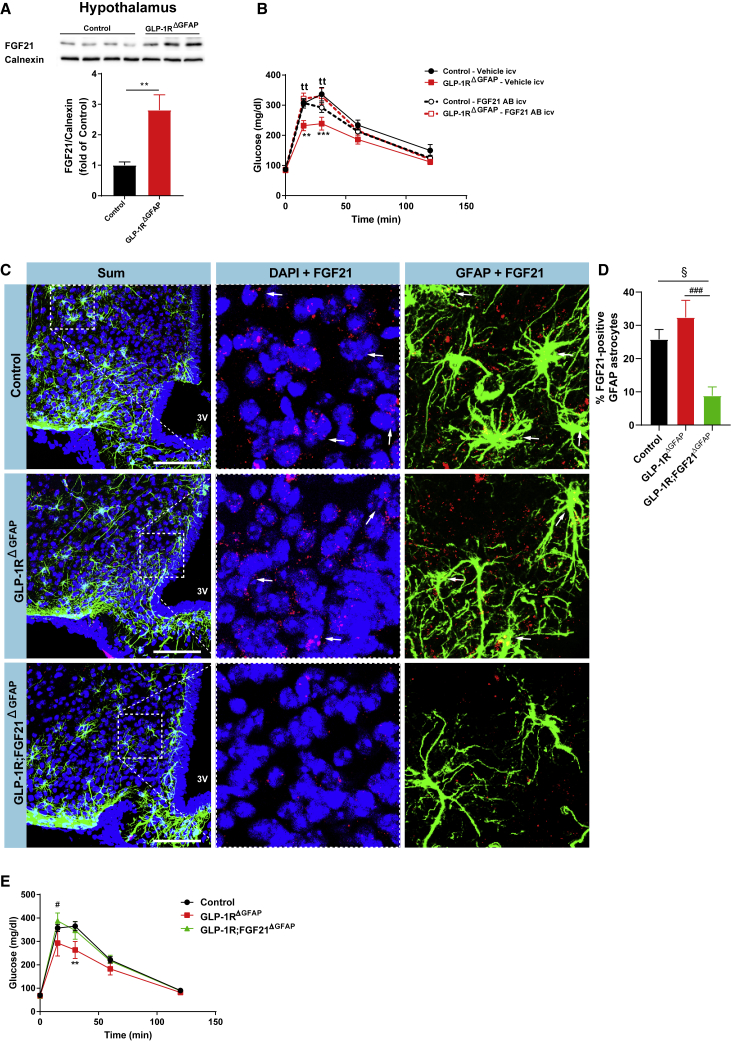

CNS-Restricted Neutralization of FGF21 or Astrocyte-Specific Ablation of FGF21 Attenuates the Improvement of Glucose Metabolism in GLP-1RΔGFAP Mice

Continuous intracerebroventricular infusion with FGF21 has been shown to increase glucose tolerance in lean rats without impacting body weight or body composition (Sarruf et al., 2010). In line with an increase in FGF21 expression upon GLP-1R ablation in primary astrocytes, we also found increased FGF21 protein expression in the hypothalamus of GLP-1RΔGFAP compared to control mice (Figure 5A). To unravel if the increase in central FGF21 mediated the improvements in systemic glucose handling in mice lacking GLP-1R expression in astrocytes, we injected mice of the different genotypes intracerebroventricularly (i.c.v.) with a neutralizing anti-FGF21 antibody (Turpin-Nolan et al., 2019) prior to a glucose tolerance test. These experiments revealed that neutralization of FGF21 in the CNS abolished the improvements in glucose tolerance in astrocyte-specific GLP-1R-deficient mice, while it did not affect glucose tolerance in lean control mice (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Neutralization of Central FGF21 or Astrocyte-Specific Ablation of FGF21 Attenuates Improvements in Glucose Metabolism in GLP-1RΔGFAP Mice

(A) Representative immunoblot and quantification of FGF21 protein expression in hypothalamic extracts of GLP-1RΔGFAP and control mice. Quantification of FGF21 levels was performed after normalization to calnexin as loading control (n = 3–4 per genotype).

(B) Glucose tolerance test (GTT) in GLP-1RΔGFAP and control mice upon intracerebroventricular injection with a neutralizing FGF21 antibody (AB) or vehicle (IgG AB) (n = 14–24 per group).

(C) Representative confocal images of in situ hybridization of mRNA of FGF21 (red), immunohistochemistry of GFAP (green), and corresponding nuclear counterstaining (DAPI, blue) in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARH) of GLP-1RΔGFAP, GLP-1R;FGF21ΔGFAP, and control mice . Arrows indicate FGF21-positive, GFAP-double-positive cells. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(D) Quantification of the percentage of FGF21-positive GFAP astrocytes per hemi-ARH (n = 8 animals per genotype).

(E) GTT in GLP-1RΔGFAP, GLP-1R;FGF21ΔGFAP, and control mice (n = 4–19 per genotype).

Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ∗∗p ≤ 0.01 (A); ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001 (GLP-1R∆GFAP-vehicle versus control-vehicle), ttp ≤ 0.01 (GLP-1R∆GFAP-FGF21 AB versus GLP-1R∆GFAP-vehicle) (B), §p ≤ 0.05 (GLP-1R;FGF21∆GFAP versus control), ###p ≤ 0.001 (GLP-1R∆GFAP versus GLP-1R;FGF21∆GFAP) (D); #p ≤ 0.05 (GLP-1R∆GFAP versus GLP-1R;FGF21∆GFAP), ∗∗p ≤ 0.01 (GLP-1R∆GFAP versus control) (E), as determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (A) and by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test (B, D, and E).

To next assess if increased brain FGF21 resulting in improvements in glucose tolerance of astrocyte-specific GLP-1R-deficient mice was astrocyte derived, we crossed GLP-1RΔGFAP mice to FGF21flox/flox mice (Potthoff et al., 2009). Further intercrossing of these animals resulted in different littermate groups of mice: (1) control animals (GLP-1Rflox/flox;FGF21wt/wt and GLP-1Rflox/flox;FGF21flox/flox mice), (2) GLP-1RΔGFAP mice lacking GLP-1R in astrocytes, and (3) GLP-1R;FGF21ΔGFAP mice lacking both GLP-1R and FGF21 expression in astrocytes upon tamoxifen application in adult mice. Astrocyte FGF21 mRNA expression was investigated in control animals, GLP-1RΔGFAP, and GLP-1R;FGF21ΔGFAP mice via fluorescent in situ hybridization (RNAscope). This analysis revealed a significantly lower percentage of FGF21-expressing GFAP-positive astrocytes in GLP-1R;FGF21ΔGFAP compared to control and GLP-1RΔGFAP mice (Figures 5C and 5D). Interestingly, improved glucose tolerance upon astrocyte-specific GLP-1R ablation was abolished in mice with simultaneous reduction of FGF21 expression in astrocytes (Figure 5E). Overall, these experiments revealed that increased astrocyte-derived FGF21 production functionally contributes to the improvements in glucose tolerance in GLP-1RΔGFAP mice.

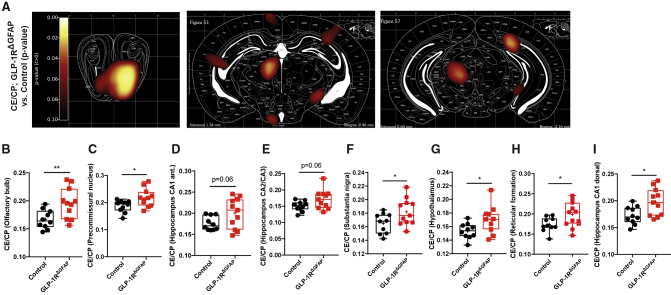

Astrocyte-Specific GLP-1R Ablation Enhances Brain Glucose Availability

As we observed increased glucose uptake in astrocytes upon GLP-1R deletion, we examined if brain glucose availability was altered in mice with astrocyte-specific GLP-1R ablation. In line with our ex vivo findings, assessment of brain glucose uptake via 18F-FDG PET scans revealed an increase in central glucose transport in various regions of the brain (Figure 6A) including the olfactory bulb (Figure 6B), the precommissural nucleus (Figure 6C), the hippocampus (Figures 6D, 6E, and 6I), the substantia nigra (Figure 6F), the hypothalamus (Figure 6G), and the reticular formation (Figure 6H), as well as in multiple other structures throughout the brain (Figure S6A), like the piriform cortex (Figure S6B), the caudate putamen (Figure S6C), the lateral septum (Figure S6D), the dorsal endopiriform nucleus (Figure S6E), the periolivary nucleus (Figure S6F), the sensory trigeminal nucleus (Figure S6G), and the hindbrain (Figure S6H), in overnight-fasted GLP-1RΔGFAP versus control mice. In contrast, glucose uptake was only very mildly increased or even decreased in distinct brain areas in non-fasted, random-fed GLP-1RΔGFAP mice compared to controls (Figures S6I–S6N). Taken together, these findings indicate that reduction of GLP-1R expression in GFAP-expressing astrocytes enhances brain glucose availability dependent on the nutritional state of the organism.

Figure 6.

Astrocyte-Specific GLP-1R Ablation Enhances Brain Glucose Availability

(A) Images showing differential regional glucose uptake in 16 h-fasted GLP-1RΔGFAP versus control animals as determined by PET-CT. Color code represents the p value for the indicated voxels in an unpaired Student’s t test in 16 h-fasted GLP-1RΔGFAP versus control animals for n = 10–11 animals per genotype. Increases in glucose uptake are shown in red.

(B–I) Quantification of brain glucose uptake in 16 h-fasted GLP-1RΔGFAP versus control animals in the (B) olfactory bulb, (C) precommisural nucleus, (D) hippocampus CA1 anterior, (E) hippocampus CA2/CA3, (F) substantia nigra, (G) hypothalamus, (H) reticular formation, and (I) hippocampus CA1 dorsal.

Results are presented as boxplots. Upper and lower whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values of the data, center lines indicate the median, and plus signs indicate the mean values. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01 as determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (B–I). See also Figures S6–S8.

As GLP-1 acutely reduced glucose uptake in primary astrocytes in vitro (Figure S2B), we next aimed to assess if acute central application of GLP-1 impacts brain glucose uptake in overnight-fasted mice in vivo. To this end, fasted C57Bl6/N mice were acutely injected i.c.v. with 1 μg GLP-1. Assessment of brain glucose uptake via 18F-FDG PET scans revealed a decrease in central glucose transport in distinct regions of the brain (Figure S7A) like the lateral septum (Figure S7B), the hypothalamus (Figure S7C), and the dorsal hippocampus (Figure S7D), in line with previous reports showing a decrease in brain glucose uptake upon acute GLP-1 administration in overnight-fasted healthy volunteers (Alvarez et al., 2005, Lerche et al., 2008). Of note, the decrease in central glucose uptake upon acute intracerebroventricular injection of GLP-1 was abrogated in fasted GLP-1RΔGFAP mice (Figures S7H–S7K) compared to control mice (Figures S7E–S7G). Thus, our experiments revealed that acute activation of cerebral GLP-1 signaling in the fasting state decreases brain glucose uptake in various regions of the brain in an astrocyte-dependent manner.

Ablation of GLP-1R in Hypothalamic GFAP Astrocytes Improves Hypothalamic Glucose Availability and Systemic Glucose Metabolism

We next intended to investigate if postnatal ablation of GLP-1R signaling specifically in hypothalamic astrocytes of the ARH recapitulates the improved glucose-regulatory phenotype of GLP-1RΔGFAP mice. To this end, we used a viral-mediated Cre/loxP approach as previously described (García-Cáceres et al., 2016) to ablate GLP-1R expression in GFAP-expressing astrocytes within the ARH. First, we confirmed that viral delivery to the ARH of GLP-1Rflox/flox mice resulted in GFP expression specifically in astrocytes of the ARH (Figures S8A and S8B). Furthermore, immunohistochemistry using liraglutide594 revealed staining of liraglutide594 in astrocytes of the ARH of control virus-treated mice, which was reduced in Cre virus-treated animals (Figures S8C and S8D). 18F-FDG PET scans in overnight-fasted mice revealed a marked increase in central glucose transport in the hypothalamus of mice with GLP-1R ablation in hypothalamic astrocytes (Figures S8E and S8F). In addition, deletion of GLP-1R in the ARH of adult mice resulted in improved glucose handling during a glucose tolerance test (Figure S8G) and enhanced insulin sensitivity during an insulin tolerance test (Figure S8H). Overall, these results revealed that ablation of GLP-1R signaling in ARH astrocytes largely recapitulated the improvements in brain and peripheral glucose handling observed in GLP-1RΔGFAP mice.

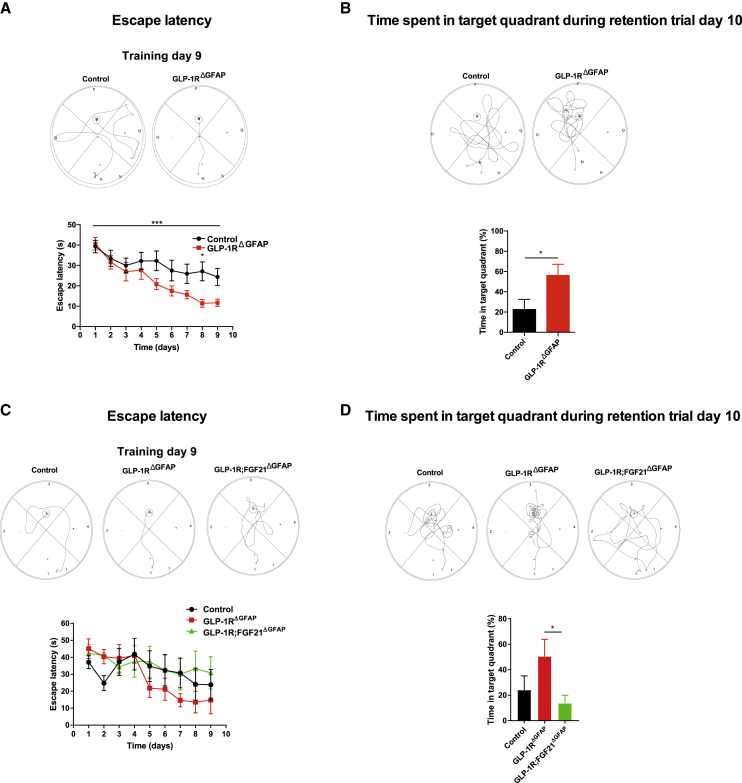

Astrocyte-Specific GLP-1R Deficiency Enhances Memory Formation in Part via FGF21 and Enhances Spontaneous Activity of Dopaminergic Midbrain Neurons

Decreased brain glucose uptake has been linked to cognitive impairment (Jais et al., 2016) and determines progression of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (Gong et al., 2006, Winkler et al., 2015). Accordingly, brain glucose availability, astrocyte glycolysis-derived lactate, and astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttling are required for long-term memory formation (Canal et al., 2005, Newman et al., 2011, Ragozzino et al., 1996, Suzuki et al., 2011). Therefore, we investigated if increased brain glucose availability in GLP-1RΔGFAP mice and enhanced astrocyte glucose uptake and glycolytic capacity in GLP-1R-deficient astrocytes translate into alterations in memory formation. To this end, astrocyte-specific GLP-1R-deficient and control mice were assessed in a spatial memory task. Indeed, GLP-1RΔGFAP mice performed significantly better compared to control mice during a Morris water maze task (Figure 7A) both during the learning phase and during the retention trial, the latter of which was more pronounced when mice were fasted before the retention trial (Figure 7B) compared to random-fed mice (Figure S9A). Of note, no difference in anxiety-related behavior (Figure S9B) or motor coordination (Figure S9C) was observed between the genotypes. As FGF21 has been shown to improve memory formation (Sa-Nguanmoo et al., 2018, Sa-Nguanmoo et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2018), we next investigated if the improvement in memory formation in astrocyte-specific GLP-1R-deficient mice was mediated, at least in part, via FGF21. To this end, GLP-1RΔGFAP, GLP-1R;FGF21ΔGFAP, and control mice were subjected to the same spatial memory learning task. Interestingly, enhanced memory formation in GLP-1RΔGFAP mice was reduced in mice lacking FGF21 in addition to GLP-1R in astrocytes (Figures 7C and 7D). Again, no differences in anxiety-related behavior (Figure S9D) or motor coordination (Figure S9E) were observed between the genotypes.

Figure 7.

Astrocyte-Specific GLP-1R Deficiency Enhances Memory Formation in an FGF21-Dependent Manner

(A) Representative swimming task and quantification of escape latency during the indicated training days of a Morris water maze task of random-fed GLP-1RΔGFAP and control mice (n = 17 per genotype).

(B) Representative swimming task and quantification of time spent in the target quadrant during retention trial upon 16 h overnight fasting (n = 6–8 per genotype) at day 10 of the Morris water maze task as described in (A).

(C) Representative swimming task and quantification of escape latency during the indicated training days of a Morris water maze task of random-fed GLP-1RΔGFAP, GLP-1R;FGF21ΔGFAP, and control mice (n = 4–6 per genotype).

(D) Representative swimming task and quantification of time spent in the target quadrant during retention trial upon 16 h overnight fasting at day 10 (n = 4–6 per genotype) of the Morris water maze task as described in (C).

Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001 as determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (A, C, and D) and unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (B). See also Figures S9 and S10.

It is often difficult to associate complex behaviors directly and causally with a single neuron type. Here, we used the dopaminergic neurons of the midbrain as an indicator population to investigate whether neurons involved in memory formation are modulated in GLP-1RΔGFAP mice. We have chosen this neuron population because it is essential for memory formation and because it can be identified in native brain slices without the need for the generation of specific genetically modified mouse models (Figures S10B and S10C). The midbrain, comprised of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), has been uncovered as an essential component for memory formation independent of the hippocampus (Da Cunha et al., 2002, Da Cunha et al., 2003, Nobili et al., 2017, Routtenberg and Holzman, 1973). Furthermore, midbrain astrocyte metabolism plays a major role in supporting the dopaminergic neurons of the SN (Kuter et al., 2019a, Kuter et al., 2019b). In line, the excitability of dopaminergic SN neurons can be modulated by KATP channels, which is crucial for novelty-induced exploratory behavior (Schiemann et al., 2012), and glucose enhances the spontaneous activity of dopaminergic SN neurons (Lutas et al., 2014). Very recently it has been demonstrated that VTA astrocytes selectively alter local GABA neurons to modulate learned behavior (Gomez et al., 2019). Thus, we hypothesized that spontaneous activity in dopaminergic midbrain neurons might be altered due to enhanced local glucose uptake in the midbrain in GLP-1RΔGFAP mice (Figure 6F). In situ hybridization revealed GLP-1R expression in GFAP astrocytes in close proximity to the SN in C57BL6/N mice (Figure S10A). To assess whether the activity of dopaminergic neurons is changed, we analyzed spontaneous firing of synaptically isolated dopaminergic SNc neurons in adult overnight-fasted GLP-1RΔGFAP and control mice (Figures S10B and S10C). To conserve the integrity of the cytosolic pathways, the recordings were performed in the perforated patch-clamp configuration. For post hoc identification, cells were loaded with biocytin by converting the perforated patch configuration to the whole-cell configuration at the end of the recording and tested for tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity (Figure S10B). These studies revealed that spontaneous firing of SNc neurons from GLP-1RΔGFAP compared to control mice indeed showed an enhanced spontaneous firing frequency (Figure S10D) as well as a smaller coefficient of variance indicating improved intrinsic pace-making properties (Figure S10E), possibly contributing to the observed improvements in learning and memory formation in GLP-1RΔGFAP mice.

Taken together, these results revealed that ablation of GLP-1R signaling in GFAP-expressing astrocytes results in improved memory formation, at least in part mediated via enhanced astrocyte-derived FGF21 and in parallel to enhanced spontaneous activity of SNc neurons.

Discussion

Mitochondria play a pivotal role in nutrient sensing and in the coordination of adaptive feedback mechanisms of hypothalamic neurons in the regulation of central energy and glucose homeostasis (Nasrallah and Horvath, 2014, Wai and Langer, 2016). Several recent studies have uncovered that astrocytes, apart from neurons, actively contribute to the control of central and systemic energy metabolism (Gao et al., 2017, García-Cáceres et al., 2016, Kim et al., 2014, Vicente-Gutierrez et al., 2019, Yang et al., 2015, Zhang et al., 2017). However, the role of mitochondrial function in astrocyte nutrient sensing and astrocyte-mediated energy and glucose homeostasis control remained largely elusive. Here we demonstrate that GLP-1R signaling is required for maintaining mitochondrial integrity and function in astrocytes, specifically at the level of the hypothalamus. Lack of GLP-1R signaling in hypothalamic astrocytes mildly impairs mitochondrial function and induces a cellular stress response, associated with increased FGF21 production, which results in an improvement in brain and systemic glucose homeostasis and enhanced memory formation.

Our findings are in line with the general observation that functional impairment of mitochondria promotes an integrated stress response, which is regulated via the transcription factor ATF4 (Melber and Haynes, 2018, Quirós et al., 2017). The canonical stress pathway induced by ATF4 leads to the upregulation of distinct ATF4 target genes like ATF5 (Melber and Haynes, 2018, Zhou et al., 2008) and FGF21 (De Sousa-Coelho et al., 2012, Kim et al., 2013, Zhou et al., 2008), a mechanism conserved across various different cell types (Khan et al., 2017, Kim et al., 2013, Pereira et al., 2017, Vandanmagsar et al., 2016), including neurons (Restelli et al., 2018). FGF21 is therefore evaluated as a possible biomarker in mitochondrial disease (Buzkova et al., 2018, Lehtonen et al., 2016, Morovat et al., 2017, Suomalainen et al., 2011).

However, besides its characteristics as a marker for mitochondrial dysfunction, FGF21 is a metabolically active polypeptide physiologically released by the liver and WAT in response to nutrient starvation (Badman et al., 2007, Inagaki et al., 2007). Moreover, FGF21 is also expressed in a variety of other different organs including muscle, pancreas, testes, heart, thymus, and brain (Fon Tacer et al., 2010). The systemic, metabolism-regulatory effects of FGF21 are complex and depend not only on the tissue-specific context but also on the metabolic status of the organism (Potthoff et al., 2009). FGF21 derived from the periphery can cross the blood-brain barrier to act in the brain, but it is also expressed in the hypothalamus (Liang et al., 2014). At the level of the CNS, FGF21 has been shown to impact systemic metabolic homeostasis as well as neuroprotection and cognition (Douris et al., 2015, Sa-Nguanmoo et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2018). Increased cerebral FGF21 levels upon continuous intracerebroventricular infusion of recombinant FGF21 enhance glucose tolerance and increase hepatic glycogen content in rats (Sarruf et al., 2010). Accordingly, enhanced production of astrocyte-derived FGF21 in mice with astrocyte-specific GLP-1R ablation resulted in improvements in systemic glucose metabolism, while we did not observe changes in body weight, body composition, or EE. Thereby, our results are in line with previous reports showing that central overexpression or prolonged central administration of FGF21 does not alter EE, body weight, or body composition in lean animals while it enhances EE and reduces body weight in obese rodents (Owen et al., 2014, Sarruf et al., 2010).

Although the improvement of brain and systemic glucose metabolism in the absence of functional GLP-1R signaling in astrocytes may appear counterintuitive in light of the beneficial metabolism-regulatory effects of GLP-1 action as well as evidence for its neuroprotective role in neurodegenerative diseases, these beneficial effects are well explained by the non-cell-autonomous effects of activating a stress response and are, at least in part, mediated through the release of FGF21. Thus, the fundamental role of GLP-1 in astrocytes appears to be its herein uncovered necessity to adapt mitochondrial dynamics, function, and fuel utilization to systemic energy availability, while the observed systemic metabolic effects arise from a compensatorily activated stress response. In fact, we view our results in line with the evolutionary conservation of such response as initially revealed already in C. elegans. Here it has been shown that mild impairment of mitochondrial function in neurons can initiate a non-cell-autonomous stress response, which even extends longevity in this model organism (Durieux et al., 2011). Thus, we provide evidence that in astrocytes of mammals, activation of a mitochondrial stress response caused by impairment of GLP-1 action may also elicit beneficial systemic effects. Collectively, the results of our study uncovered a critical role of GLP-1R signaling in the maintenance of astrocyte mitochondrial integrity and unveiled how the astrocyte mitochondrial stress response impacts systemic and brain glucose homeostasis as well as memory formation.

Limitations of Study

While our in vitro studies in cultured primary astrocytes clearly demonstrate a previously unrecognized role for GLP-1 signaling to regulate fuel utilization as well as mitochondrial dynamics and function in this cell type, the overall metabolic changes observed upon astrocyte-restricted reduction of GLP-1R-signaling in vivo appear to arise from the activation of an integrated stress response and are, at least in part, mediated by increased astrocyte-derived FGF21 acting in the CNS. While these results highlight the functional significance of GLP-1R signaling for controlling astrocyte mitochondrial function in vivo, this leaves open what the direct physiological consequences of GLP-1R action in this cell type are in vivo. Here, further extensive studies of mice with reduced GLP-1R and FGF21 expression in astrocytes may highlight the physiological consequences of reduced astrocyte GLP-1R signaling when at the same time the compensatory stress response is attenuated.

Moreover, most of the conclusions of the current study are derived from either cultured astrocytes in the presence or absence of altered GLP-1R signaling or mice with astrocyte-specific deletion of the GLP-1R, thereby limiting our experimental models to cell-type-selective GLP-1R deficiency. Thus, reconstitution experiments re-expressing the GLP-1R specifically in astrocytes of conventional GLP-1R knockout mice may provide another avenue for future investigation to further define the physiological role of GLP-1R action in astrocytes.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-NDUFA9 (Complex I) | Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 459100; RRID: AB_2532223 |

| Anti-NDUFB8 (Complex I) | Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 459210; RRID: AB_2532232 |

| Anti-Complex II 70 kDa Fp Subunit | Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 459200; RRID: AB_2532231 |

| Anti-UQCRC1 (Complex III) | Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 459140; RRID: AB_2532227 |

| Anti-Subunit Va (Complex IV) | Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 459110; RRID: AB_2532224 |

| Anti-ATP synthase subunit β (Complex V) | Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 21351; RRID: AB_221512 |

| Anti-calnexin | Merck Millipore | Cat# 208880; RRID: AB_2069031 |

| Anti-GLUT-1 | Merck Millipore | Cat# 07-1401; RRID: AB_1340 |

| Anti-pGLUT-1 (Ser-226) | Merck Millipore | Cat# ABN991 |

| Anti-TOM20 | Cell Signaling | Cat# sc-11415; RRID: AB_2207533 |

| Anti-GFAP | Abcam | Cat# 7260; RRID: AB_305808 |

| Anti-Akt | Cell Signaling | Cat# 4685; RRID: AB_2225340 |

| Anti-pAkt (S473) | Cell Signaling | Cat# 4060; RRID: AB_2315049 |

| Anti-FGF21 | R&D Systems | Cat# AF3057; RRID: AB_2104611 |

| Anti-IgG Control | R&D Systems | Cat# AB-108-C; RRID: AB_354267 |

| Anti-GLP-1R | Novus Biologicals | Cat# NBP1-97308; RRID: AB_11139100 |

| Anti-GFP | Abcam | Cat# 13970; RRID: AB_300798 |

| Anti-TH | Abcam | Cat# 76442; RRID: AB_1524535 |

| Alexa 488 donkey-anti-rabbit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-21206; RRID: AB_2535792 |

| Alexa 488 goat-anti-rabbit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-11008; RRID: AB_143165 |

| FITC goat-anti-chicken | Jackson Laboratories | Cat# 103-095-155; RRID: AB_2337384 |

| Alexa 647 donkey-anti-rabbit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-31573; RRID: AB_2536183 |

| Alexa 633–conjugated streptavidin | Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# S-21375; RRID: AB_2313500 |

| Dylight 488 anti-chicken IgG | Abcam | Cat# 96947; RRID: AB_10681017 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| AAV5-GFAP(2.2)-iCre | Vector BioLabs | VB1172 |

| AAV5-GFAP(2.2)-eGFP | Vector BioLabs | VB1180 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| AdenoBOOST | Sirion Biotech | Cat# SB-P-AV-101-02 |

| Biocytin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# B4261 |

| DAPI-containing vectashield | Vector Laboratories | Cat# VEC-H-1200 |

| GLP-1 7-36 amide | Bachem | Cat# H-6795 |

| WZB117 | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# SML0621 |

| 20% Glucose | bela-pharm | Cat# 2069.97.99 |

| Insulin | Sanofi Aventis, Germany | Insuman rapid |

| Liraglutide594 | Novo Nordisk | N/A |

| Seahorse XF Palmitate-BSA FAO Substrate | Agilent Technologies | Cat# 102720-100 |

| Tamoxifen | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# T5648-5G |

| TSA Plus Cyanine 3 | Perkin Elmer | Cat# NEL744E001KT |

| TSA Plus Cyanine 5 | Perkin Elmer | Cat# NEL745E001KT |

| Chemicals used in Primary Cell Cultures | ||

| DMEM high glucose, GlutaMAX | GIBCO, ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 10569010 |

| DMEM | GIBCO, ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 11966-025 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Pan Biotech | Cat# P30-3302 |

| Penicillin/Streptomycin | GIBCO, ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 15140-122 |

| HBSS, no calcium, no magnesium | Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 14170112 |

| L-15 medium | GIBCO, ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 11415064 |

| D-(+)-Glucose solution 45% in H2O | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# G8769 |

| L-Carnitine hydrochloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# C0283-1G |

| Etomoxir | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# E1905-25MG |

| HEPES solution | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# H0887-100ML |

| Poly-L-Lysine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# P-4707 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| QIAshredder (250) | QIAGEN | Cat# 79656 |

| RNeasy Mini Kit (250) | QIAGEN | Cat# 74106 |

| Applied Biosystems High-Capacity CDNA Reverse Transcription Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 4368813 |

| Applied Biosystems TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 10733457 |

| Mouse GLP-1 ELISA | Crystal Chem, USA | Cat# 81508 |

| Mouse ultra-sensitivity insulin ELISA | Crystal Chem, USA | Cat# 90080 |

| Human Ultrasensitive Insulin ELISA | DRG Instruments GmbH | Cat# EIA-2337 |

| Mouse Leptin ELISA | Crystal Chem, USA | Cat# 90030 |

| Picoprobe Glucose Assay | Abcam | Cat# ab169559 |

| Glucose Uptake Cell-Based Assay | Cayman Chemical, USA | Cat# Cay-600470 |

| Pierce BCA Protein Assay | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 23225 |

| L-Lactate Assay | Abcam | ab65331 |

| Dental acrylic Super Bond C&B | Sun Medical | Cat# 7100 |

| XF Cell Mito Stress Test Kit | Agilent Technologies | Cat# 101706-100 |

| TSA Plus Fluorescence kit | Perkin Elmer, USA | Cat# NEL741001KT |

| RNAscope Enhancer Fluorescent Kit v2 | ACD | Cat# 323100 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6N | Charles River | N/A |

| Mouse: hGFAP-CreERT2 | (Ganat et al., 2006) | N/A |

| Mouse: GLP-1R-flox | (Jun et al., 2014) | N/A |

| Mouse: GLP-1R deficient (GLP-1RΔ/Δ) | (Scrocchi et al., 1996) | N/A |

| Mouse: FGF21-flox | (Potthoff et al., 2009) | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Taqman probe mGLP1-R | ThermoFisher Scientific | Mm00445292_m1 |

| Taqman probe HPRT | ThermoFisher Scientific | Mm01545399_m1 |

| Taqman probe ATF4 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Mm00515324_m1 |

| Taqman probe ATF5 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Mm04179654_m1 |

| Taqman probe Ddit3 (CHOP) | ThermoFisher Scientific | Mm00492097_m1 |

| Taqman probe Hspa5 (BIP) | ThermoFisher Scientific | Mm00517691_m1 |

| Taqman probe Ppara (PPARα) | ThermoFisher Scientific | Mm00440939_m1 |

| Taqman probe FGF21 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Mm00840165_g1 |

| Custom-designed qPCR probes targeting hGLP1-R construct: Flag primer 5′ 913: GGACTACAAGGATGACGACGAC, 3′ 3580-152: CCCAAGGCACACAAAA AACC and mUTRprobe: 5′ FAM TGGCCATCCCAGGTGGGAGAGA TCCT 3′TAMRA |

Eurogentec | https://secure.eurogentec.com/life-science.html |

| mitochondrial Nd2: fw: 5′- AGGG ATCCCACTGCACATAG-3′; rev: 5′- CTCCTCATGCCCCTATGAAA-3′ |

Eurogentec | https://secure.eurogentec.com/life-science.html |

| mitochondrial D-Loop: fw: 5′- GGTTC TTACTTCAGGGCCATCA-3′, rev: 5′- GATTAGACCCGATACCATCGAGAT-3′ |

Eurogentec | https://secure.eurogentec.com/life-science.html |

| nuclear Nduv: fw: 5′- CTTCCC CACTGGCCTCAAG-3′; rev: 5′- CCAAAACCCAGTGATCCAGC-3′ |

Eurogentec | https://secure.eurogentec.com/life-science.html |

| Custom-designed RNA scope probe targeting the region 108 - 1203 of the GLP1R transcript | ACD | Cat# NM_021332.2 |

| Custom-designed RNA scope probe targeting the region 5 - 904 of the FGF21 transcript | ACD | Cat# NM_020013.4 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 6 and 7 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Fiji (ImageJ) Software Package (incl. Adiposoft Plugin) | (Schneider et al., 2012) | https://imagej.net/Adiposoft |

| IVIS LivingImage Software V4.3.1 | Caliper LifeScience, Perkin Elmer, USA | https://www.perkinelmer.de/category/in-vivo-imaging-software |

| Vinci software package 4.61.0 | (Cízek et al., 2004) | https://vinci.sf.mpg.de/ |

| TargetLynx Software | Waters | https://www.waters.com/waters/library.htm?locale=en_US&lid=1545580 |

| Wave Desktop | Agilent Technologies | https://www.agilent.com/en/products/cell-analysis/cell-analysis-software/data-analysis/wave-desktop-2-6 |

| PatchMaster (version 2.32) | HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany | https://www.heka.com/downloads/downloads_main.html |

| Patcher’s Power Tools plug-in | MPI, Neher Lab; programmed in IGOR Pro 6, Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA | https://www.mpibpc.mpg.de/groups/neher/index.php?page=software |

| CED 1401 with Spike2 (version 7) | Cambridge Electronic Design Ltd., Cambridge, UK | http://ced.co.uk/de/ |

| Other | ||

| Regular Chow Diet | sniff Spezialdiäten GmbH, Germany | R/M-H phytoestrogen-low |

| IVIS Spectrum CT scanner | Caliper LifeScience, Perkin Elmer, USA | Cat# 128201 |

| Indirect calorimetry system ‘‘PhenoMaster’’ | TSE systems, Chesterfield, USA | http://www.tse-systems.com/products/metabolism/home-cage/phenomaster/index.htm |

| XFe96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer, “Seahorse” | Agilent Technologies | https://www.agilent.com/en/products/cell-analysis/seahorse-analyzers/seahorse-xfe96-analyzer |

| Inveon preclinical PET/CT system | Siemens | N/A |

| Dionex ICS-6000 HPIC system | Thermo Fisher Scientific | https://www.thermofisher.com/de/de/home/industrial/chromatography/ion-chromatography-ic/ion-chromatography-systems/modular-ic-systems.html |

| Vibrating Microtome VT1200s | Leica Microsystems | https://www.leicabiosystems.com/histology-equipment/sliding-and-vibrating-blade-microtomes/vibrating-blade-microtomes/leica-vt1200-s/ |

| Leica TCS SP-8-X Confocal microscope | Leica Microsystems | https://www.leica-microsystems.com/products/confocal-microscopes/p/leica-tcs-sp8-x/ |

| AB-QuantStudio 7 Flex | Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat# 4485701 |

| Inline solution heater | Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA | Cat# SH27B |

| Temperature controller | Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA | Cat# TC-324B |

| Electrode glass | Science Products | Cat# GB150-8P |

| Vertical pipette puller | Narishige, London, UK | Cat# PP-830 |

| EPC10 patch-clamp amplifier | HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany | https://www.heka.com/ |

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Jens C. Brüning (bruening@sf.mpg.de).

Materials Availability

No unique reagents were generated in this study.

Data and Code Availability

There were no datasets generated in this study.

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Animal Care

All animal procedures were conducted in compliance with protocols approved by the local government authorities (Bezirksregierung Köln) and were in accordance with NIH guidelines. Mice were housed in groups of 3–5 at 22 C°–24 C° using a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. Animals had ad libitum access to water and the prescribed diet at all times, and food was only withdrawn if required for an experiment. Animals were fed a regular chow diet containing 57% calories from carbohydrates, 34% calories from protein, and 9% calories from fat (R/M-H; Sniff Diet). For all experiments only male mice were used. All experiments were performed in adult mice at the age of 16-28 weeks.

Generation of Transgenic Mice

GLP-1RΔGFAP Mice

hGFAP-CreERT2 mice were mated with GLP-1Rflox/flox mice (Jun et al., 2014) and breeding colonies were maintained by mating GLP-1Rflox/flox females to hGFAP-CreERT2; GLP-1Rflox/flox males. Mice were kept on a C57BL/6 background throughout the experiment. Tamoxifen application was performed at 8-9 weeks of age as previously described (Koch et al., 2008).

GLP-1R;FGF21ΔGFAP

GLP-1RΔGFAP mice were mated with FGF21flox/flox mice (Potthoff et al., 2009) and breeding colonies were maintained by mating hGFAP-CreERT2tg/wt; GLP-1Rflox/flox; FGF21flox/wt to hGFAP-CreERT2wt/wt; GLP-1Rflox/flox; FGF21flox/wt mice. Tamoxifen application at 8-9 weeks of age allowed for postnatal deletion of either only GLP-1R or GLP-1R and FGF21 in GFAP-expressing astrocytes (resulting littermate groups of mice: (1) control animals (GLP-1Rflox/flox;FGF21wt/wt and GLP-1Rflox/flox;FGF21flox/flox, i.e. hGFAP-CreERT2-negative mice), (2) GLP-1RΔGFAP mice lacking GLP-1R expression in astrocytes and (3) GLP-1R;FGF21ΔGFAP lacking both GLP-1R and FGF21 expression in astrocytes).

GLP-1RΔ/Δ Mice

Whole-body male GLP-1R-deficient mice (GLP-1RΔ/Δ mice) (Scrocchi et al., 1996) were kindly provided by Daniel J. Drucker.

C57Bl6/N Mice

Male C57Bl6/N mice were purchased from Charles River.

Isolation and Culturing of Primary Hypothalamic Mouse Astrocytes

Hypothalamic explants were isolated from male pups at postnatal day 1-3 and were dissociated to single cells as follows: hypothalamic explants were isolated and meninges were carefully removed using an ultrafine forceps under the microscope. Afterward, the hypothalamic explants were transferred to ice-cold L-15 medium (#11415064, GIBCO, ThermoFisher Scientific) and dissected using a sharp blade. Hypothalamic tissue pieces were then transferred to pre-warmed HBSS medium (#14170112, GIBCO, ThermoFisher Scientific) and placed into the incubator at 37°C for 10 min with intermittent slight movement. Afterward, tissue pieces were transferred to a 15 mL falcon with 1X HBSS + 0.25% of trypsin (final volume 5 ml) and incubated at 37°C for 20 min with intermittent movement. Thereafter, the falcon was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 37°C. The supernatant was carefully discarded and complete medium (containing of DMEM high glucose, GlutaMAX supplement, #10569010, GIBCO, ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, #P30-3302, PAN Biotech) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (#15140-122, GIBCO, ThermoFisher Scientific) was added and the pellet was gently dissociated by pipetting up-and-down before another centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 37°C. Afterward, the supernatant was carefully discarded, complete medium was added and the pellet was again gently dissociated by pipetting up-and-down. After another centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 37°C and after discarding the supernatant, cells were dissociated again in complete medium, counted and seeded in 25cm2 flasks with complete medium at 5% CO2, 37°C. After 8 days in culture, flasks were shaken on an orbital shaker at 180 rpm for 30 min to remove microglia (Schildge et al., 2013). After exchanging the medium, flasks were shaken for additional 6 h at 240 rpm to remove oligodendrocyte precursor cells (Schildge et al., 2013), followed by an additional medium change and further culturing.

Method Details

Glucose Tolerance and Insulin Tolerance Tests

Glucose Tolerance Tests

Glucose tolerance tests were performed in the morning after an overnight fasting period of 16 h. Glucose concentrations in blood were measured from whole venous blood using an automatic glucose monitor (Bayer Contour, Bayer, Germany). After the fasting period, each mouse received an intraperitoneal injection of 20% glucose (2 g per kg body weight; bela-pharm) and blood glucose concentrations were measured before and after 15, 30, 60 and 120 min.

Insulin Tolerance Tests

Insulin tolerance tests were performed in the morning in random fed mice. After determination of basal blood glucose concentrations, each mouse received an intraperitoneal injection of insulin (0.375 U per kg body weight; Insuman Rapid; Sanofi Aventis) and glucose concentrations in the blood were measured after 15, 30, 60 and 120 min.

Serum Analyses

Serum insulin and leptin levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay according to vendor’s instructions (mouse ultra-sensitive Insulin ELISA, mouse Leptin ELISA; Crystal Chem, USA).

Analysis of Total GLP-1 in Hypothalamic Explants, the Rest-Brain and in Plasma

Hypothalamic explants and rest-brains were lysed in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% TritonX and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) and were homogenized using an homogenizer (IKA T10 basic Ultra Turrax). Then, homogenized samples were incubated for 1 h at 4°C and centrifuged at 3000 g, for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C. To measure the amount of GLP-1 in plasma, blood from random-fed animals was collected in tubes which contained EDTA, centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and stored at −80°C. Afterward, total GLP-1 content in homogenized hypothalamic explants, the rest-brain and plasma was assessed using a mouse GLP-1 ELISA according to vendor’s instructions (Crystal Chem, USA). The GLP-1 amount in the hypothalamic and the rest-brain samples was normalized to sample protein concentrations measured via the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fischer).

Liver Glycogen Measurement

Liver glycogen was assessed in random-fed GLP-1RΔGFAP and control mice as previously described (Brandt et al., 2015, Passonneau et al., 1967). In brief, liver samples were incubated in pre-cooled (4°C) 0.5 M PCA (perchloride acid, readymade, diluted in ddH2O) and incubated on ice for min 20 min. Thereafter, samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm 15 min at 4°C. Afterward, the supernatant was removed and acidified with 1 M HCl and then boiled at 100°C for 2 h. Following, 10 M NaOH + 1 M HEPES were added and samples were centrifuged at 13000 rpm, 20 min, 4°C. The supernatant was removed and assessed for protein content using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo FischerScientific) kit and for glucose content using the Picoprobe Glucose Assay kit (Abcam).

Euglycemic-Hyperinsulinemic Clamp Studies in Awake, Free-Moving Animals

Implantation of catheters into the jugular vein and the clamp procedure employed were performed as described before (Könner et al., 2007, Timper et al., 2018). In brief, mice were anesthetized using a ketamine-dexmedetomidine combination and then a saline filled catheter (Micro-Renathane, MRE 025; Braintree Scientific, Braintree, Massachusetts, USA) was inserted into the right internal jugular vein and advanced to the level of the superior vena cava. The catheter was filled with heparin, tunneled, and attached to an adaptor that was positioned in a subcutaneous pocket at the back of the neck, allowing for direct connection of the catheter with the infusion line on the day of experimentation. After 5–6 days of recovery, mice that had lost less than 10% of their preoperative weight were subjected to the clamp study. On the day of experimentation, each animal was deprived of food for 4 h in the morning before placement in the customized clamp-box, allowing for unrestrained, free movements of the mice during the clamp procedure. For clamp studies, D-[3-3H]-glucose (PerkinElmer) was administered as a bolus (5 μCi), and then infused continuously (0.05 μCi/min). All solutions infused were prepared with 3% plasma added, obtained from 4 h fasted donor mice. Hyperinsulinemia was achieved by a bolus infusion of insulin (Insuman Rapid; Sanofi Aventis) of 20 μU/g body weight, and thereafter by infusing insulin at a fixed rate of 4 μU/g/min. Blood glucose concentrations were monitored regularly according to a fixed scheme from tail vein bleedings (B-glucose analyzer, Hemocue), and maintained at around 120-140 mg/dl by administering 20% glucose (bela-pharm). An infusate of 2-deoxy-D-[1-14C]-glucose (10 μCi; American Radiolabeled Chemicals) was given approximately 120 min before steady state for analysis of tissue specific glucose uptake. Steady state was considered achieved, when a fixed glucose-infusion rate maintained the glucose concentration in blood constant for 30 min. At the end of the experiment, mice were killed by decapitation and liver, perigonadal WAT, BAT, SKM and brain were dissected, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further analysis. The [3-3H]glucose content in serum during basal conditions and at steady state was measured as described earlier (Könner et al., 2007). The radioactivity of 2-[1-14C]-deoxy-d-glucose in plasma was measured directly in a liquid scintillation counter. Lysates of WAT, BAT, SKM and brain were processed through ion-exchange chromatography columns (AGR1-X8 formate resin, 200–400 mesh dry; Poly-Prep Prefilled Chromatography Columns; Bio Rad Laboratories) for the separation of 2-[1-14C]-deoxy-d-glucose from 2-[1-14C]-deoxy-d-glucose-6-phosphate, 2-[1-14C] (2DG6P). The glucose-turnover rate (mg/kg/min) was calculated as described (Könner et al., 2007). Tissue specific glucose uptake in brain, WAT, BAT and SKM was calculated on the basis of the accumulation of 2-[1-14C]-deoxy-d-glucose-6-phosphate, 2-[1-14C] in the respective tissue and the disappearance rate of 2-[1-14C]-deoxy-d-glucose from plasma (Ferré et al., 1985) and expressed as nanomol per gram of tissue per minute (nmol/g/min). For evaluation of basal and steady-state clamped insulin serum levels, an ultrasensitive insulin ELISA for determination of human insulin was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions (Ultrasensitive ELISA, #EIA-2337, DRG Instruments GmbH).

Indirect Calorimetry

Indirect calorimetry was performed using an open-circuit, indirect calorimetry system (PhenoMaster, TSE systems) as previously described (Mauer et al., 2014). In brief, mice were trained for three days before data acquisition to adapt to the food/drink dispenser of the PhenoMaster system. Afterward mice were placed in regular type II cages with sealed lids at room temperature (22°C) and allowed to adapt to the chambers for at least 24 h. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All parameters were measured continuously and simultaneously.

Assessment of Body Composition

Lean and fat mass were analyzed by computed tomography (CT) in isoflurane-anesthetized mice (Dräger and Piramal Healthcare). For data acquisition on an IVIS Spectrum CT scanner (Caliper LifeScience, USA) we used IVIS LivingImage Software V4.3.1. Quantification of lean and fat mass contents were determined with a modification of the previously described Vinci software package 4.61.0 (Cízek et al., 2004) developed at our institution (available at: https://vinci.sf.mpg.de/).

Morris Water Maze

The Morris Water Maze was used to test spatial memory and to evaluate the working and reference memory functions as previously described (Jais et al., 2016). Mice were assessed at 20-22 weeks of age. The water maze consists of a circular pool (diameter of 120 cm) filled with water (21–22°C). Hidden-platform training (acquisition phase) was conducted with the platform placed in the northeast quadrant 1 cm below the water surface over 9 consecutive days (4 trials/day). Several large visual cues were placed in the room to guide the mice to the hidden platform. Each training trial was finished when the mouse reached the platform (escape latency) or after 60 s. Mice failing to reach the platform were guided onto it. After each training trial, mice remained on the platform for 15 s. To test memory retention, retention trials were performed at day 10 of the test with 16 h-fasted or random-fed mice, respectively, as indicated. In the retention trial, the platform was removed from the pool and mice were allowed to swim for 60 s. The percent of time spent in the target quadrant was recorded. All trials were monitored by a video camera set above the center of the pool and connected to a video tracking system (TSE systems).

Open Field

Open-field experiments were performed in an open-field box for mice during the light cycle (TSE Systems, Bad Homburg, Germany) as previously described (Hess et al., 2013). Mice were placed in the open-field box and the time at the center and the border (in %) as well as the distance traveled (in cm) and the speed (cm/s) for each mouse was measured over a period of 45 min using an automated video-based system in an open field (50 cm × 50 cm; VideoMot 2, TSE Systems, Bad Homburg, Germany).

Rotarod

In the rotarod test, the mice were placed on a horizontally oriented, 2 cm rotating cylinder (rod). The rotation speed of the rod was accelerating starting at 4 rpm and increasing continuously up to 40 rpm after 300 s. Every animal was placed on the rotating rod four times with 15 min recovery in between each trial. The length of time that the mice stayed on the rotating rod (fall latency) was measured via light beam detection. The average fall latency of four test trials per mouse was calculated.

Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV)-Injection

AAV injection in the ARH was performed as described (García-Cáceres et al., 2016). In brief, adult, 8-9 week-old GLP-1Rflox/flox mice were anesthetized using a ketamine-dexmedetomidine combination and were placed into a stereotaxic apparatus. 0.25 μL of an adeno-associated virus (AAV)5, allowing for Cre-expression (AAV5-hGFAP-iCre; Vector BioLabs) or GFP expression (AAV5-hGAP-eGFP; Vector BioLabs) under the control of the hGFAP promotor in astrocytes was injected into the upper and lower left and right ARH using appropriate coordinates: upper left ARH (anteroposterior (AP): - 1.5 mm, medio-lateral (ML): - 0.3 mm; dorso-ventral (DV): - 5.8 mm), lower left ARH (AP: - 1.5 mm, ML: - 0.3 mm, DV: - 5.9 mm), upper right ARH (AP: - 1.5 mm, ML: + 0.3 mm, DV: - 5.8 mm), lower right ARH (AP: - 1.5 mm, ML: + 0.3 mm, DV: - 5.9 mm).

Intracerebroventricular Injections

Icv Cannulation

Icv cannulations were performed as described previously (Timper et al., 2017). Briefly, adult mice were anesthetized using a ketamine-dexmedetomidine combination and were placed into a stereotaxic apparatus. 26 gauge cannulas were implanted to the left lateral ventricle using appropriate coordinates (bregma, - 0.2 mm, + 1 mm; dorsal surface, - 2.1 mm). Dental acrylic (Super Bond C&B) was used to secure the cannula to the skull surface. Animals were allowed to recover for at least 1 week prior to experiment. After experiments, stereotaxic implants were anatomically verified.

Icv FGF21 Antibody Administration

For icv injection, mice were administered with 2 μl of a neutralizing FGF21 antibody (goat IgG, dissolved in sterile PBS, 2 μg per mouse, #AF3057, R&D Systems) or control (goat IgG, dissolved in sterile PBS, 2 μg per mouse, #AB-108-C, R&D Systems) when removing food for the 16 h starvation period ahead of the GTT.

Icv GLP-1 Administration

After an overnight fasting period of 16 h, mice were icv injected with 2 μl of either saline (control) or 1 μg of GLP-1 (GLP-1 7-36 amide; #H-6795, Bachem, Switzerland) 5 min before injecting the [18F]FDG and starting the PET scans as outlined below. Icv GLP-1 or saline administration with subsequent PET imaging was conducted in a crossover fashion with a one week wash-out period between the experiments.

Assessment of Brain Glucose Uptake via 18F-FDG PET Scans

PET imaging was performed using an Inveon preclinical PET/CT system (Siemens). Random-fed or 16 h-fasted mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane in 65%/35% nitrous oxide/oxygen gas and positioned on a dedicated mouse carrier (MEDRES, Germany) carrying two mice. Body temperature was maintained at 37.0 ± 0.5°C by a thermostatically controlled water heating system. For injection of the radiotracer, a catheter consisting of a 30 G cannula connected to a polythene tubing (ID = 0.28 mm) was inserted into the tail vein and fixated by a drop of glue. After starting the PET scan, 7-8 MBq of [18F]FDG in 50-100 μL saline were injected per mouse. Emission data were acquired for 45 min. Thereafter, animals were automatically moved into the CT gantry and a CT scan was performed (180 projections/360°, 200 ms, 80 kV, 500 μA). The CT data were used for attenuation correction of the PET data and the CT image of the scull was used for image co-registration. Plasma glucose levels were determined from a tail vein blood sample using a standard glucometer (Bayer) after removing the tail vein catheters. PET data were histogrammed in time frames of 12x30 s, 3x60 s, 3x120 s, 7x240 s, Fourier rebinned, and images were reconstructed using the MAPSP algorithm provided by the manufacturer. For co-registration the imaging analysis software Vinci was used (Cízek et al., 2004). Images were co-registered to a 3D mouse brain atlas constructed from the 2D mouse brain atlas published by Paxinos and Franklin (2013).

Kinetic Modeling

An image-derived input function was extracted from the PET data of the aorta, which could be identified in the image of the first three to five time frames of each animal. Input function data were corrected for partial volume effect by assuming a standardized volume fraction of 0.6 (Green et al., 1998). Parametric images of the [18F]FDG kinetic constants K1, k2, k3, and k4 were determined by a voxel-by-voxel (voxel size = 0.4 mm x 0.4 mm x 0.8 mm) fitting of data to a two- tissue-compartment kinetic model. K1 is the constant for transport from blood to tissue, k2 for transport from tissue to blood, k3 the constant for phosphorylation of [18F]FDG to [18F]FDG-6-phosphate, and k4 the constant for dephosphorylation. Additional parametric images of the cerebral metabolic rate of glucose and the extracellular glucose level were calculated. The cerebral metabolic rate of glucose was calculated taking into account the different efficiencies of [18F]FDG and glucose, a method that is insensitive to changes of the lumped constant (Backes et al., 2011):

| CMRglc = Kglc × CP |

| Kglc = Ki / (0.38 + 1.10 Ki / K1) |

| Ki = K1 × k3 / (k2 + k3) |

| CE = K1 / (k2 + k3 / 0.26) × CP |

CP indicates the plasma glucose level. CE/CP is the ratio of extracellular to plasma glucose and was used to quantify glucose uptake.

Statistics

Statistical testing was performed by application of a voxel-wise t test between groups. 3D maps of p values allow for identification of regions with significant differences in the parameters. From these regions we defined volumes of interest (VOIs) and performed additional statistical testing for these VOIs. For presentation only, 3D maps of p values were re-calculated on a 0.1 mm x 0.1 mm x 0.1 mm grid from the original dataset using trilinear interpolation.

Analysis of Gene Expression

RNA was isolated from primary astrocytes using the RNeasy Kit (QIAGEN) according to manufacturer’s suggestions. RNA was reversely transcribed with High Capacity cDNA RT Kit and amplified using TaqMan Universal PCR-Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). All samples were treated with DNase. Relative expression of target mRNAs was adjusted for total RNA content by Hprt (Mm01545399_m1). Inventoried Taqman probes were used: ATF4 Mm00515324_m1, ATF5 Mm04179654_m1, Hspa5 (BIP) Mm00517691_m1, Ddit3 (CHOP) Mm00492097_m1, Ppara (Pparα) Mm00440939_m1, FGF21 (Mm00840165_g1), mouse GLP-1R (Mm00445292_m1). To assess GLP-1R knock-out efficiency in primary astrocytes the following designed probes were used: Flag primer 5′913: GGACTACAAGGATGACGACGAC, 3′ 3580-152: CCCAAGGCACACAAAAAACC, mUTRprobe: 5′ FAM TGGCCATCCCAGGTGGGAGAGATCCT 3′TAMRA. Calculations were performed by a comparative method (2−ΔΔCT). Quantitative PCR was performed on an AB-QuantStudio 7 Flex (Applied Biosystems).

Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA