Abstract

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is often unsuccessful for monosomal karyotype (MK) acute myeloid leukemia (AML). To what degree failures are associated with pre-transplant measurable residual disease (MRD) – a dominant adverse risk factor – is unknown. We therefore studied 606 adults with intermediate- or adverse-risk AML in morphologic remission who underwent allogeneic HCT between 4/2006 and 1/2019. Sixty-eight (11%) patients had MK AML, the majority of whom with complex cytogenetics. Before HCT, MK AML patients more often tested MRDpos by multiparameter flow cytometry (49% vs. 18%; P<0.001) and more likely had persistent cytogenetic abnormalities (44% vs. 13%; P<0.001) than non-MK AML patients. Three-year relapse/overall survival estimates were 46%/43% and 72%/15% for MRDneg and MRDpos MK AML patients, respectively, contrasted to 20%/64% and 64%/38% for MRDneg and MRDpos non-MK AML patients, respectively. After multivariable adjustment, MRDpos remission status but not MK remained statistically significantly associated with shorter survival and higher relapse risk. Similar results were obtained in several patient subsets. In summary, while our study confirms higher relapse rates and shorter survival for MK-AML compared to non-MK AML patients, these outcomes are largely accounted for by the presence of other adverse prognostic factors, in particular higher likelihood of pre-HCT MRD.

INTRODUCTION

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is highly heterogenous with treatment outcomes that vary substantially between individual patients.1,2 Among the many established prognostic factors, cytogenetic abnormalities play a central role in the risk categorization and development of risk-stratified treatment algorithms. While classification schemes have evolved with better understanding of the prognostic significance of recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities and slightly differing schemes are used by different groups, they have traditionally separated patients crudely into “favorable”, “intermediate”, and “adverse” risk groups.2–7

Still, even among patients with adverse-risk karyotypes, results with conventional chemotherapy and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) are not uniform.8 A seminal study identified a monosomal karyotype (MK; karyotype with ≥2 autosomal monosomies or 1 autosomal monosomy with ≥1 structural abnormality) as a new cytogenetic entity with particularly low probability of long-term survival with standard chemotherapy (4-year estimates of <5%).8 Numerous studies have subsequently confirmed this association.9–21 While results with allogeneic HCT appear better than with non-HCT post-remission therapies, several studies – including one from our institution – have reported poor post-HCT outcomes for adults with MK AML.10–12,14,15,18–22

Based on these data, it is now generally accepted that having MK AML is an important adverse prognostic factor for patients undergoing allogeneic HCT. However, to what degree these outcomes are accounted for by the presence of measurable (‘minimal’) residual disease (MRD) before HCT is unknown. This is particularly important because multivariable models from several transplant and non-transplant studies suggest the presence of MRD is the dominant risk factor for adverse treatment outcome that largely, albeit not completely, accounts for the prognostic significance of adverse-risk cytogenetics.23–25 To study the relationship between MK, pre-HCT MRD and post-HCT outcomes, we examined a large cohort of adults with AML who underwent allogeneic HCT in first or second complete remission (CR) at our institution between April 2006 and January 2019 and whom we had data from available for multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC)-based MRD testing before HCT.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study cohort

Adults 18 years of age or older with AML (2016 WHO criteria26) were included if 1) they had their first allogeneic HCT with peripheral blood or bone marrow as a stem cell source while in first or second morphologic remission and 2) data were available from routine karyotyping at the time of AML diagnosis. We included all patients from 4/2006 (when a refined ten-color MFC-based MRD assay was introduced and utilized routinely in all HCT patients) until 1/2019. Results from 437 of the 606 patients in the final dataset have been partially reported in previous publications.23,24,27–32 All patients were treated on Institutional Review Board-approved research protocols or standard treatment protocols and gave consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Follow-up was current as of October 30, 2019.

Classification of disease risk at diagnosis and cytogenetic analysis at the time of HCT

We used the refined MRC/NCRI criteria6 to assign cytogenetic risk at diagnosis based on local cytogenetic data. At the time of HCT, marrow and/or blood samples were examined for cytogenetic abnormalities as part of our institutional pre-transplant work-up using standard G-banding techniques and karyotyped according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature.33 We included numerical aberrations and structural abnormalities in our analysis. An abnormality was considered clonal when at least two metaphases had the same aberration in case of a structural abnormality or an extra chromosome. In case of a monosomy, it had to be present in at least three metaphases. In case of a missing number of analyzed metaphases in the records, but fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) showing the same abnormalities as the G-banding analysis, this karyotype was also considered to be clonal. We considered independent structural abnormalities and/or numerical aberrations but not marker chromosomes for the designation of complex karyotypes. Among the 606 patients, 248 had a normal karyotype based on ≥20 normal metaphases examined (n=197) or <20 metaphases examined (n=51); following the approach by Breems and colleagues,8 all of these patients were considered to have cytogenetically normal AML.

MFC detection of MRD

Ten-color MFC was performed in all patients as a routine clinical test on bone marrow aspirates obtained before conditioning therapy was started as described previously.23,24,27–29 MRD was identified by visual inspection as a cell population showing deviation (typically seen in more than one antigen) from the normal patterns of antigen expression found on specific cell lineages at specific stages of maturation as compared with either normal or regenerating marrow based on the tested antibody panel.23,24,27–29 The assay is able to detect MRD in the large majority of cases down to a level of 0.1% and in progressively smaller subsets of patients as the level of MRD decreases below that level. When identified, the abnormal population was quantified as a percentage of the total CD45+ white cell events. Any measurable level of MRD was considered positive.23,24,27–29

Statistical Analysis

Unadjusted probabilities of relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and probabilities of relapse were summarized using cumulative incidence estimates. NRM was defined as death without prior relapse and was considered a competing risk for relapse. Cox regression and competing risk sub-distribution regression models were used to assess covariate associations with outcomes. Covariates evaluated were: MK (yes vs. no), first or second remission at time of HCT (remission 1 vs. remission 2), pre-HCT MRD (yes vs. no), conditioning regimen (MAC vs. RIC), cytogenetic risk group at time of AML diagnosis (intermediate vs. adverse), type of AML at diagnosis (secondary vs. de novo), presence of complex cytogenetics (yes vs. no), karyotype at time of HCT (normalized vs. not normalized for patients presenting with abnormal karyotypes), peripheral blood counts at the time of HCT (recovered vs. not recovered), age at time of HCT, and white blood cell (WBC) count at time of diagnosis. Categorical patient characteristics were compared using Fisher’s exact test and quantitative characteristics were compared with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Two-sided p-values are reported. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 16.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and R (http://www.r-project.org).

RESULTS

Characteristics of study cohort

We identified 705 adults with AML undergoing a first allogeneic MAC, RIC, or Mini HCT in first or second morphologic remission between 4/2006 and 1/2019. Excluding patients who did not agree to their data being used for research purposes (n=9), those who did not undergo MRD testing at our institution during the pre-HCT work-up (n=10), those with favorable-risk cytogenetics (n=46; MK is only defined for patients with intermediate- and adverse-risk cytogenetics8), and those with unknown karyotype at the time of AML diagnosis (n=34), our study cohort was comprised of 606 patients. Among these, 68 (11%) had MK AML, including 59 (87%) with complex cytogenetics with ≥3 abnormalities and 56 (82%) with complex cytogenetics with ≥4 abnormalities, compared to 46 (9%) and 23 (4%) of the 538 patients with non-MK AML (both P<0.001). Basic characteristics of the study population and HCT details are summarized in Table 1. There were several statistically significant differences between patients with MK AML and those with non-MK AML. Specifically, MK AML patients more often had adverse-risk and complex cytogenetics (both P<0.001), had a lower WBC at diagnosis (P=0.0001), and more often had secondary AML (P=0.003). Their duration of remission before HCT was shorter (P=0.0054) and they more often were transplanted in first remission (P=0.004). Importantly, MK AML patients more often were MRDpos than non-MK AML patients (49% vs. 18%; P<0.001) and more likely had persistent cytogenetic abnormalities at the time of HCT (44% vs. 13%; P<0.001).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of entire study cohort, stratified by monosomal and non-monosomal karyotype

| Monosomal karyotype (n=68) |

Non-monosomal karyotype (n=538) |

All patients (n=606) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at diagnosis (range), years | 56 (20–76) | 56 (18–77) | 56 (18–77) | 0.50 |

| Median age at HCT (range), years | 56 (20–77) | 57 (18–80) | 57 (18–80) | 0.64 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 41 (60%) | 292 (54) | 333 (55) | 0.37 |

| HCT-CI, n (%) | 0.90 | |||

| 0 | 5 (8) | 43 (9) | 48 (9) | |

| 1–2 | 19 (31) | 167 (34) | 186 (33) | |

| ≥3 | 38 (61) | 285 (58) | 323 (58) | |

| Missing | 6 | 43 | 49 | |

| Median WBC at diagnosis (range), x103/μL | 1.9 (0.2–126.0) | 8.0 (0.4–347.5) | 6.9 (0.2–347.5) | 0.0001 |

| Cytogenetic risk, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Intermediate | 1 (1) | 430 (80) | 431 (71) | |

| Adverse | 67 (99) | 108 (20) | 175 (29) | |

| Complex cytogenetics, n (%) | ||||

| ≥3 abnormalities | 59 (87) | 46 (9) | 105 (17) | <0.001 |

| ≥4 abnormalities | 56 (82) | 23 (4) | 79 (13) | <0.001 |

| Secondary AML | 0.003 | |||

| No | 37 (54) | 390 (72) | 427 (70) | |

| Yes | 31 (46) | 148 (28) | 179 (30) | |

| Median CR duration before HCT (range), days | 85 (16–356) | 99 (11–574) | 98 (11–574) | 0.0054 |

| Remission status, n (%) | 0.004 | |||

| First remission | 63 (93) | 422 (78) | 485 (80) | |

| Second remission | 5 (7) | 116 (22) | 121 (20) | |

| Pre-HCT MRD status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| MRDneg | 35 (51) | 443 (82) | 478 (79) | |

| MRDpos | 33 (49) | 95 (18) | 128 (21) | |

| Median % abnormal blasts (range) | 0.2 (0.007–10.0) | 0.8 (0.007–19.4) | 0.49 (0.007–19.4) | |

| Recovered peripheral blood counts before HCT*, n (%) | 51 (75) | 382 (71) | 433 (71) | 0.57 |

| Recovered ANC before HCT*, n (%) | 62 (91) | 499 (93) | 561 (93) | 0.62 |

| Recovered platelet count before HCT*, n (%) | 51 (75) | 388 (72) | 439 (72) | 0.67 |

| Routine karyotyping before HCT, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Normalized karyotype | 37 (54) | 190 (35) | 227 (37) | |

| Abnormal karyotype | 30 (44) | 71 (13) | 101 (17) | |

| Missing/non-informative data | 1 (1) | 277 (51) | 278 (46) | |

| Unrelated donor, n (%) | 47 (69) | 360 (67) | 407 (67) | 0.79 |

| HLA matching, n (%) | 0.37 | |||

| Fully matched | 55 (81) | 454 (84) | 509 (84) | |

| 1-allele mismatch | 9 (13) | 67 (12) | 76 (13) | |

| 2-allele mismatch | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | |

| Haplo-identical | 4 (6) | 13 (2) | 17 (3) | |

| Conditioning regimen | 0.64*** | |||

| MAC | 42 (62) | 316 (59) | 358 (59) | |

| Containing high-dose TBI (≥12 Gy) | 6 (9) | 42 (8) | 48 (8) | |

| Not containing high-dose TBI | 36 (53) | 274 (51) | 310 (51) | |

| RIC | 13 (19) | 92 (17) | 105 (17) | |

| Mini** | 13 (19) | 130 (24) | 143 (24) | |

| Stem cell source, n (%) | 0.14 | |||

| PBSC | 57 (84) | 484 (90) | 541 (89) | |

| BM | 11 (16) | 54 (10) | 65 (11) |

ANC ≥1,000/μL and platelets ≥100,000/μL.

Conditioning with fludarabine and TBI 2–3 Gy.

Comparison MAC vs. RIC vs. Mini.

Abbreviations: ANC, absolute neutrophil count; BM, bone marrow; FLU, fludarabine; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; HCT-CI, HCT-specific Comorbidity Index; MAC, myeloablative conditioning; MRD, measurable residual disease; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cells; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning; TBI, total body irradiation; WBC, total white blood cell count.

Relationship between pre-HCT MRD status and post-HCT outcome for MK AML and non-MK AML patients in the entire study cohort

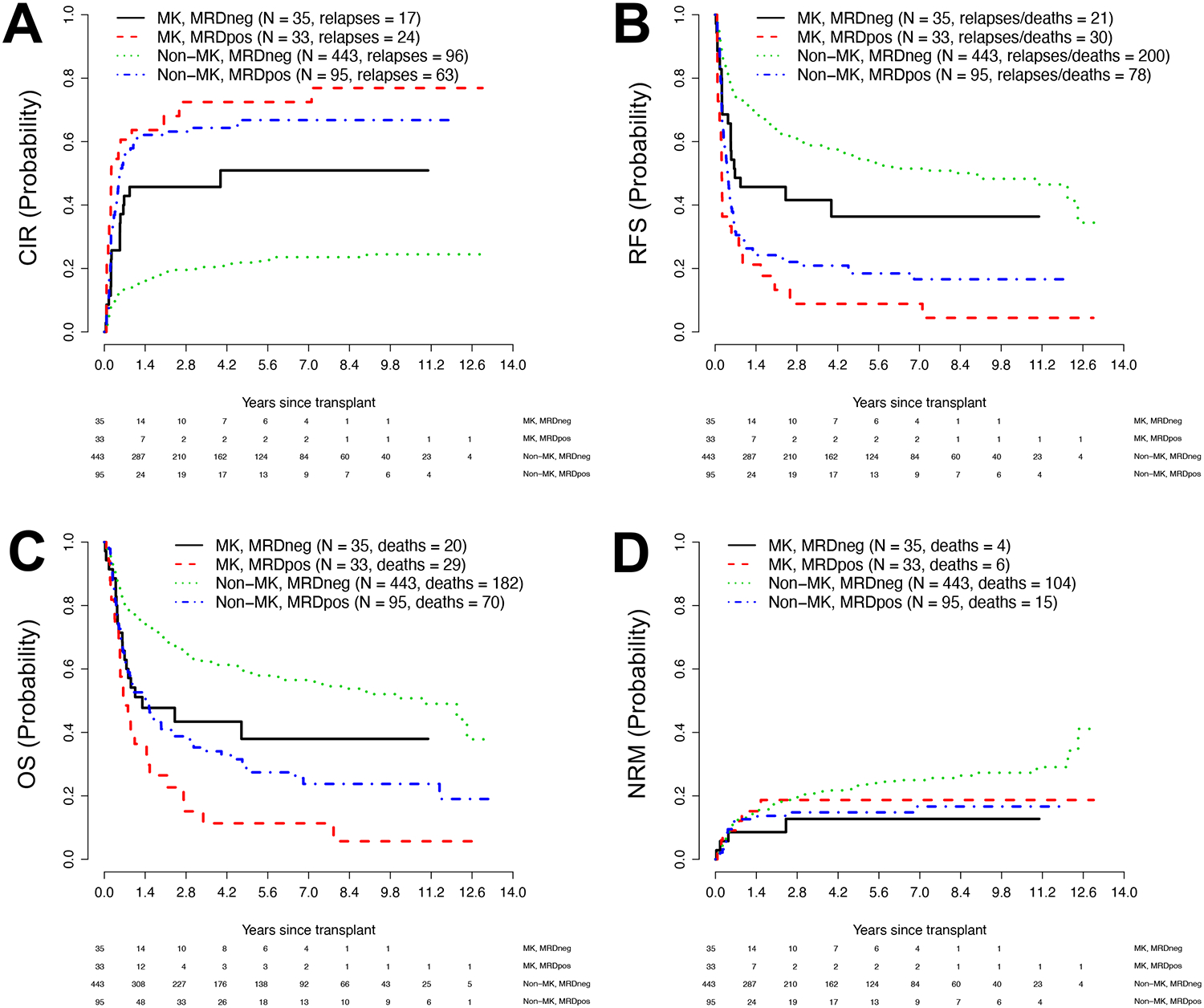

By the day of data cut-off, 200 of the 606 patients (41 with MK-AML) relapsed of whom 172 (39 with MK-AML) have died. One hundred and twenty-nine patients (10 with MK-AML) experienced NRM, for a total of 301 deaths (49 among MK-AML patients) following transplantation (Table 2). The median follow-up time after HCT in the 305 patients alive at last contact was 63.6 (range 8.4–158.0) months (for MK-AML patients [n=20]: 41.5 [9.9–155.5] months; for non-MK AML patients [n=295]: 65.0 [8.4–158.0] months). Consistent with our previous analyses,23,24,27–29 the 128 patients with MRD before HCT had a significantly higher risk of relapse and shorter RFS as well as shorter OS than the 478 MRDneg patients whereas the risk of NRM was similar (Table 3). Similarly in line with a previous report from our institution,11 the 68 patients with MK AML had a significantly higher risk of relapse and shorter RFS and OS but not NRM than the 538 non-MK AML patients (Table 3). The relapse risk remained higher, and RFS and OS shorter, for MK AML patients even when stratified by pre-HCT MRD status (Figure 1 and Table 3). Specifically, among MRDneg patients, estimates for the 3-year cumulative incidence of relapse, 3-year RFS, and 3-year OS were 46% (95% confidence interval: 29–63%), 42% (28–66%), and 48% (43–62%) for MK AML and 20% (16–24%), 60% (55–65%), and 64% (59–68%) for non-MK AML, respectively. Among the MRDpos patients, estimates for relapse incidence, RFS, and OS at 3 years were 72% (55–90%), 9% (4–30%), and 15% (6–36%) for MK AML and 64% (55–74%), 21% (14–31%), and 38% (29–49%) for non-MK AML.

TABLE 2.

Number of events in entire study population and stratified by monosomal and non-monosomal karyotype conditioning therapy (n=606)

| Relapses | Deaths with prior relapse | Deaths without prior relapse | Total number of deaths | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 200 | 172 | 129 | 301 |

| MK AML | 41 | 39 | 10 | 49 |

| Non-MK AML | 159 | 133 | 119 | 252 |

TABLE 3.

Outcome probabilities (with 95% confidence interval) of entire study cohort stratified by monosomal karyotype and pre-HCT MRD status

| CI of relapse at 3 years | RFS at 3 years | OS at 3 years | CI of NRM at 3 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | ||||

| All (n=606) | 31% (27–35%) | 50% (46–54%) | 56% (52–60%) | 19% (16–22%) |

| MRDneg (n=478) | 22% (18–26%) | 58% (54–63%) | 62% (58–67%) | 20% (16–24%) |

| MRDpos (n=128) | 66% (58–74%) | 18% (13–27%) | 32% (25–41%) | 16% (9–22%) |

| Monosomal karyotype | ||||

| All (n=68) | 59% (46–71%) | 26% (17–40%) | 29% (19–43%) | 16% (6–25%) |

| MRDneg (n=35) | 46% (29–63%) | 46% (32–66%) | 43% (29–65%) | 13% (1–25%) |

| MRDpos (n=33) | 72% (55–90%) | 9% (4–30%) | 15% (6–36%) | 19% (5–33%) |

| Non-monosomal karyotype | ||||

| All (n=538) | 28% (24–32%) | 53% (49–57%) | 59% (54–63%) | 19% (16–23%) |

| MRDneg (n=443) | 20% (16–24%) | 60% (55–65%) | 64% (59–68%) | 20% (17–24%) |

| MRDpos (n=95) | 64% (55–74%) | 21% (14–31%) | 38% (29–49%) | 15% (8–22%) |

Abbreviations: CI, cumulative incidence; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; MRD, measurable residual disease; NRM, non-relapse mortality; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival.

Figure 1. Association between pre-transplant MRD status and post-transplant outcome for 68 adults with MK AML and 538 adults with non-MK AML undergoing allogeneic HCT while in first or second morphologic remission.

Estimates of (A) cumulative risk of relapse (CIR), (B) relapse-free survival (RFS), (C) overall survival (OS), and (D) cumulative risk of non-relapse mortality (NRM) following allogeneic HCT. Outcome estimates are shown individually for MK AML patients in MRDneg remission (n=35) or MRDpos remission (n=33) as well as non-MK AML patients in MRDneg remission (n=443) or MRDpos remission (n=95), respectively.

We then developed uni- and multivariable regression models for relapse, RFS, OS, and NRM. In the entire cohort, the unadjusted hazard ratio of MK AML vs. non-MK AML for relapse was 2.78 (1.96–3.94, P<0.001; Table 4), the unadjusted hazard ratio for failure for RFS was 2.20 (1.63–2.96, P<0.001), and the unadjusted hazard ratio for overall mortality was 2.22 (1.63–3.02, P<0.001). For MRDpos vs. MRDneg remission, unadjusted hazard ratios were 4.56 (3.44–6.06; P<0.001) for relapse, 3.06 (2.42–3.86; P<0.001) for RFS, and 2.40 (1.89–3.05; P<0.001) for overall mortality. As summarized in Table 4, statistically significant associations with relapse, RFS, and/or OS were also found for several other covariates including WBC at the time of AML diagnosis, and age at time of transplantation, cytogenetic risk, presence of complex (≥4) cytogenetic abnormalities, remission status (first vs second remission), conditioning intensity, and karyotype at the time of HCT but not type of AML (secondary vs. de novo). After adjustment for various covariates as summarized in Table 5, being MRDpos before transplantation was associated with significantly increased relapse risk (HR=3.88 [2.83–5.31], P<0.001), shorter RFS (HR=2.72 [2.10–3.52], P<0.001), and shorter OS (hazard ratio [HR]=2.03 [1.55–2.66], P<0.001) relative to being MRDneg before transplantation. On the other hand, having MK AML was not independently associated with relapse (P=0.30), RFS (P=0.35), or OS (P=0.24) in our multivariable models.

TABLE 4.

Univariate regression models for entire study cohort (n=606)

| Relapse | Failure for RFS | Overall mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monosomal karyotype | |||

| No (n=538) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes (n=68) | 2.78 (1.96–3.94), P<0.001 | 2.20 (1.63–2.96), P<0.001 | 2.22 (1.63–3.02), P<0.001 |

| Pre-HCT MRD Status | |||

| MRDneg (n=478) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| MRDpos (n=128) | 4.56 (3.44–6.06), P<0.001 | 3.06 (2.42–3.86), P<0.001 | 2.40 (1.89–3.05), P<0.001 |

| Remission status | |||

| First remission (n=485) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Second remission (n=121) | 1.63 (1.19–2.23), P=0.003 | 1.49 (1.16–1.92), P=0.002 | 1.47 (1.13–1.91), P=0.004 |

| Conditioning Regimen | |||

| MAC (n=358) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| RIC/Mini (n=248) | 1.29 (0.97–1.70), P=0.08 | 1.57 (1.26–1.95), P<0.001 | 1.64 (1.30–2.06), P<0.001 |

| Age (per 10 years) | 0.99 (0.88–1.10), P=0.80 | 1.10 (1.01–1.19), P=0.032 | 1.14 (1.05–1.25), P=0.003 |

| WBC at diagnosis (per 10,000/μL) (n=596) | 1.01 (0.91–1.11), P=0.91 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04), P=0.019 | 1.02 (1.00–1.05), P=0.018 |

| Cytogenetic risk | |||

| Intermediate (n=431) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Adverse (n=175) | 1.87 (1.41–2.48), P<0.001 | 1.26 (1.00–1.60), P=0.048 | 1.14 (0.89–1.46), P=0.29 |

| Complex karyotype* | |||

| No (n=527) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes (n=79) | 2.55 (1.83–3.56), P<0.001 | 1.85 (1.38–2.47), P<0.001 | 1.91 (1.41–2.57), P<0.001 |

| Type of AML | |||

| De novo (n=427) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Secondary (n=179) | 0.97 (0.72–1.32), P=0.86 | 1.07 (0.84–1.35), P=0.58 | 1.14 (0.89–1.45), P=0.30 |

| Pre-HCT karyotype | |||

| Normalized (n=227) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Not normalized (n=101) | 1.95 (1.36–2.77), P=0.001 | 1.81 (1.35–2.43), P<0.001 | 1.74 (1.28–2.38), P<0.001 |

| Pre-HCT blood counts** | |||

| Recovered (n=433) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Not recovered (n=173) | 1.01 (0.74–1.38), P=0.95 | 1.35 (1.07–1.71), P=0.011 | 1.53 (1.20–1.94), P=0.001 |

≥4 cytogenetic abnormalities.

Recovered: ANC ≥1,000/μL and platelets ≥100,000/μL; not recovered: ANC <1,000/μL and/or platelets <100,000/μL.

TABLE 5.

Multivariable regression models of entire study cohort

| Relapse | Failure for RFS | Overall mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monosomal karyotype | |||

| Yes (vs. no) | 1.36 (0.76–2.42), P=0.30 | 1.27 (0.77–2.08), P=0.35 | 1.38 (0.81–2.36), P=0.24 |

| Pre-HCT MRD Status | |||

| MRDpos (vs. MRDneg) | 3.88 (2.83–5.31), P<0.001 | 2.72 (2.10–3.52), P<0.001 | 2.03 (1.55–2.66), P<0.001 |

| Remission status | |||

| Second (vs. first) remission | 1.96 (1.37–2.80), P<0.001 | 1.63 (1.23–2.15), P=0.001 | 1.46 (1.09–1.94), P=0.010 |

| Conditioning Regimen | |||

| RIC/Mini (vs. MAC) | 1.64 (1.16–2.30), P=0.001 | 1.81 (1.39–2.35), P<0.001 | 1.67 (1.27–2.21), P<0.001 |

| Age (per 10 years) | 0.90 (0.79–1.05), P=0.10 | 0.97 (0.88–1.07), P=0.51 | 1.01 (0.91–1.12), P=0.89 |

| WBC at diagnosis (per 10,000/μL) | 1.03 (1.00–1.05), P=0.038 | 1.04 (1.02–1.06), P<0.001 | 1.04 (1.01–1.06), P=0.001 |

| Complex karyotype* | |||

| Yes (vs. no) | 1.42 (0.85–2.40), P=0.18 | 1.35 (0.85–2.14), P=0.21 | 1.54 (0.93–2.55), P=0.093 |

| Pre-HCT karyotype | |||

| Not normalized (vs. normalized) | 1.33 (0.90–1.87), P=0.15 | 1.36 (0.98–1.88), P=0.06 | 1.17 (0.82–1.65), P=0.38 |

| Pre-HCT blood counts** | |||

| Not recovered (vs. recovered) | 0.71 (0.49–1.02), P=0.06 | 1.00 (0.78–1.29), P=0.99 | 1.25 (0.97–1.62), P=0.08 |

≥4 cytogenetic abnormalities.

Recovered: ANC ≥1,000/μL and platelets ≥100,000/μL; not recovered: ANC <1,000/μL and/or platelets <100,000/μL.

Relationship between pre-HCT MRD status and post-HCT outcome for MK AML and non-MK AML in distinct patient subsets

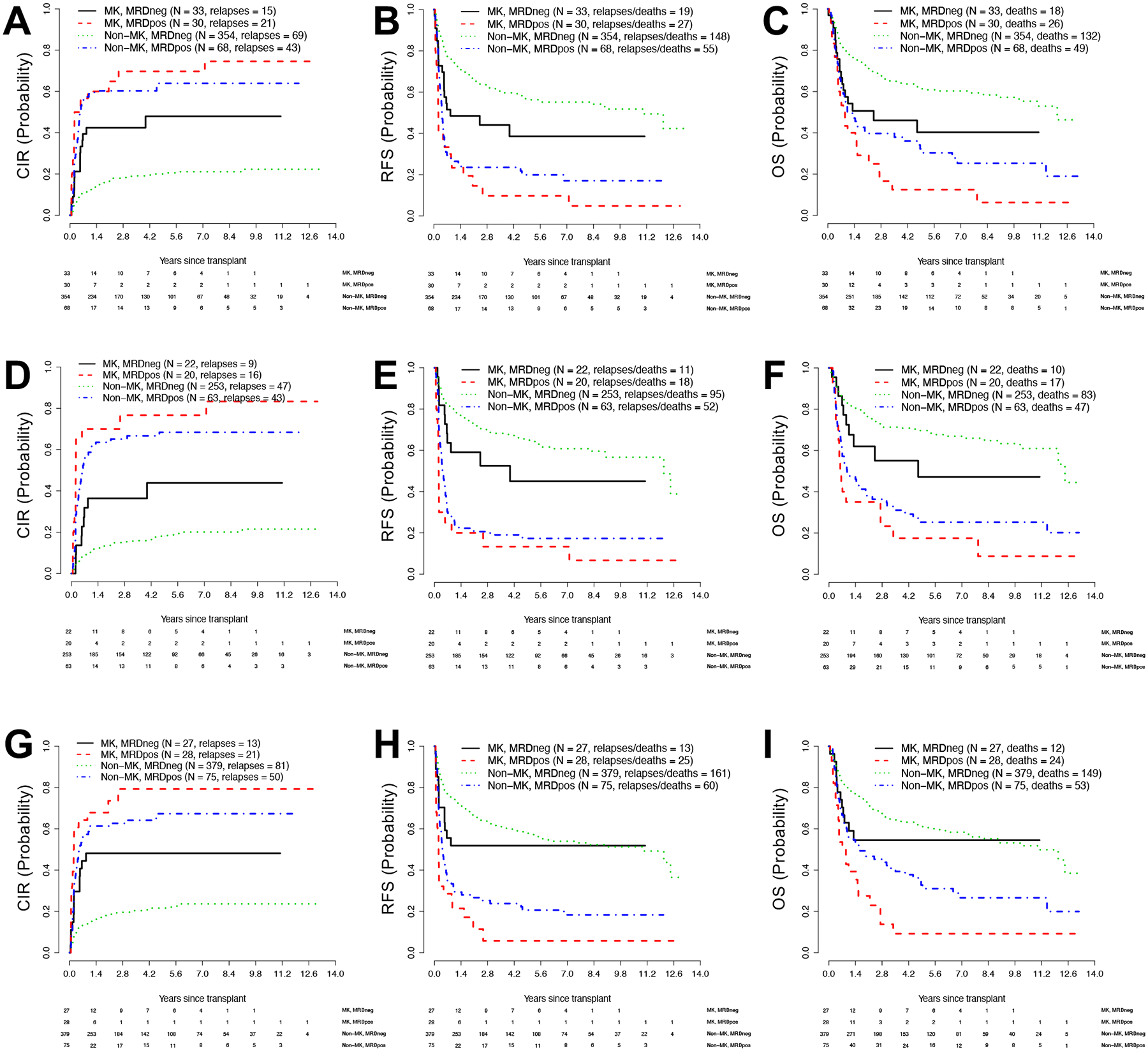

We performed subset analyses to examine the relationship between pre-HCT MRD status and outcomes in MK AML and non-MK AML separately in patients transplanted in first remission, those who underwent transplantation after myeloablative conditioning, and those receiving a fully HLA-matched allograft. Among the 485 patients transplanted in first remission, 63 (13%) had MK AML. Basic characteristics of these patients and the 422 non-MK AML patients are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Estimates of relapse, RFS, and OS are depicted in Figure 2A–C. As shown in Supplementary Table 2, we found very similar hazard ratios for having MK AML vs. not having MK AML as those obtained in the entire study cohort with regard to relapse (HR=2.00 [1.98–4.24], P<0.001), RFS (HR=2.27 [1.65–3.13], P<0.001), and OS (HR=2.27 [1.63–3.16], P<0.001). Similar to what we found in the entire study cohort, having MK AML was no longer independently associated with relapse (P=0.58), RFS (P=0.53), or OS (P=0.47) after multivariable adjustment whereas being MRDpos remained independently associated with higher risk of relapse (HR=4.17 [2.88–6.04], P<0.001), shorter RFS (HR=3.16 [2.34–4.28], P<0.001), and shorter OS (HR=2.39 [1.73–3.28], P<0.001; Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 2. Post-transplant outcomes for distinct subsets of patients with MK AML and non-MK AML, stratified by pre-transplant MRD status.

Estimates of (A) cumulative risk of relapse (CIR), (B) relapse-free survival (RFS), and (C) overall survival (OS) for adults with MK AML (n=63) or non-MK AML (n=422) undergoing allogeneic HCT while in first morphologic remission. Estimates of (D) CIR, (E) RFS, and (F) OS for adults with MK AML (n=42) or non-MK AML (n=316) undergoing allogeneic HCT in first or second morphologic remission after myeloablative conditioning. Estimates of (G) CIR, (H) RFS, and (I) OS for adults with MK AML (n=55) or non-MK AML (n=454) undergoing HCT in first or second morphologic remission with HLA-matched allografts.

Among the 358 patients who underwent myeloablative HCT, 42 (12%) had MK AML. Basic characteristics of these patients and the 316 non-MK AML patients are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. Estimates of relapse, RFS, and OS in this patient subset are depicted in Figure 2D–F. As shown in Supplementary Table 5, hazard ratios for having MK AML vs. not having MK AML were 2.91 (1.85–4.58) for relapse (P<0.001), 2.13 (1.43–3.17) for RFS (P<0.001), and 2.05 (1.35–3.10) for OS (P=0.001). After multivariable adjustment, having MK AML was no longer independently associated with relapse (P=0.48), RFS (P=0.60), or OS (P=0.36) whereas being MRDpos remained independently associated with higher risk of relapse (HR=6.10 [4.06–9.18], P<0.001), shorter RFS (HR=4.05 [2.90–5.67], P<0.001), and shorter OS (HR=3.08 [2.17–4.37], P<0.001; Supplementary Table 6).

Finally, among the 509 patients who underwent HCT with HLA-matched allografts (55 [11%] of whom had MK AML; Supplementary Table 7), estimates of relapse, RFS, and OS are shown in Figure 2G–I. As summarized in Supplementary Table 8, hazard ratios for having MK AML vs. not having MK AML were 3.13 (2.11–4.64) for relapse (P<0.001), 2.17 (1.53–3.06) for RFS (P<0.001), and 2.11 (1.48–3.01) for OS (P<0.001). After multivariable adjustment, having MK AML was no longer independently associated with relapse (P=0.35), RFS (P=0.51), or OS (P=0.41) whereas being MRDpos remained independently associated with higher risk of relapse (HR=3.95 [2.78–5.62], P<0.001;), shorter RFS (HR=2.79 [2.08–3.73], P<0.001), and shorter OS (HR=2.01 [1.48–2.74], P<0.001; Supplementary Table 9).

DISCUSSION

Several studies have indicated that adults with MK AML are essentially non-curable with conventional chemotherapies.8,9,12,13,17,20 Although some of the reported outcomes with allogeneic HCT seemed better than what was observed with other post-remission therapies, the recurrent notion that relapse rates are very high and survival estimates short after transplantation10–12,14,15,18–22 may have decreased enthusiasm to expose patients to the risks associated with allografting. The findings from our large retrospective single-institution study confirm that adults with intermediate- or adverse-risk AML and MK have worse post-HCT outcomes than corresponding patients without MK AML, with the 3-year cumulative incidence of relapse approaching 60% in our cohort of MK AML patients (as compared to less than 30% for the non-MK AML patients). Nonetheless, their relapse-free and overall survival estimates range between 25% and 30%. While this is substantially lower than the estimates for non-MK AML patients (around 55–60%), our data suggest a significant subset of MK AML patients will experience longer-term AML-free survival after allogeneic HCT, lending support for the continued use of this treatment strategy for MK AML.

As key finding in our study, post-HCT outcomes are not uniform among adults with MK AML. Rather, our study is the first to identify the MRD status before HCT as a critically important prognostic factor in this subset of AML patients. Perhaps not surprisingly given their relative resistance to conventional chemotherapies, we found a much higher proportion of MK AML patients to have evidence of residual disease during the pre-transplant work-up. Specifically, as assessed by MFC, MK AML patients were almost 3-times as likely to have MRD at that time than those with non-MK AML. Relative to MK AML patients in MRDneg remission, patients with MK AML in MRDpos remission had a significantly higher risk of relapse within 3 years (72% vs. 46%) and lower 3-year estimates of RFS (9% vs. 46%) and OS (15% vs. 43%). In univariate analyses, both having MK AML and presence of MRD were statistically significantly associated with increased relapse risk as well as shorter RFS and OS. Without adjustment, hazard ratios for MK AML vs. non-MK AML and MRDpos vs. MRDneg remission were relatively similar. After accounting for several covariates (age, WBC at diagnosis, presence of complex karyotype, first vs. second remission, karyotype at the time of HCT, peripheral blood counts at the time of HCT, and conditioning intensity), having MRD at the time of HCT remained statistically highly significantly associated with higher relapse risks and shorter survival, similar to what we and others have previously reported.25,34 On the other hand, after multivariable adjustment, having MK AML was no longer statistically significantly associated with higher relapse risks or shorter survival. We obtained qualitatively similar results in our entire study cohort as well as subset analyses, in which we focused on patients transplanted in first morphologic remission, those who received myeloablative conditioning, and those who received fully HLA-matched allografts. Together, these models suggest that the worse outcomes after allogeneic HCT observed in MK AML compared to non-MK AML are largely accounted for by the presence of other adverse prognostic factors, in particular MRD, rather than having MK AML per se. From a clinical perspective, these findings suggest that close attention should be paid to the MRD status of MK AML patients considered for allogeneic HCT for informed decision-making and the development of novel treatment strategies aimed to improve post-HCT outcomes for MK AML.

As a particular strength of our study, bone marrow assessment that includes MFC-based MRD testing is routinely performed as part of the pre-HCT work-up since 2006 in a largely unchanged fashion. With this, we were able to include essentially all adults with AML undergoing allogeneic HCT in first or second morphologic remission in our analysis. As a result, ours is the largest single-institution study to date examining post-transplant outcomes of MK AML patients. During that period, patients with AML were routinely assigned to myeloablative conditioning unless significant comorbidities were present, or patients were enrolled onto trials comparing conditioning intensities. Results from pre-HCT MRD testing were available to the treating physicians for all patients comprising our study cohort. However, while the presence of MRD was perceived as a marker for increased risk of post-HCT disease recurrence, it typically played no major role in the selection of the type of preparative regimen.

As one important limitation of our study, the majority of patients was referred to our institution for transplantation after receiving induction and consolidation chemotherapy elsewhere. Therefore, molecular testing, including for mutations in NPM1, FLT3, CEBPA, ASXL1, and RUNX1, was not routinely performed and data on mutations could thus not be included in our analyses. We also did not have information on mutations in TP53 routinely available, mutations of particular interest for patients with MK AML given the strong association between MK AML and TP53 abnormalities.35–38 Other study limitation to consider include its retrospective nature, the fact that transplant protocol assignments were done in a non-randomized fashion, the relatively short follow-up time for patients transplanted most recently in our cohort, and the relative small number of MK patients, resulting in relatively large confidence intervals for outcome estimates. Moreover, some subset analyses of potential interest, e.g. assessing the relations of MK, pre-HCT MRD, and post-transplant outcomes in people transplanted in second remission or those receiving non-myeloablative conditioning, could not be done because of limited sample sizes in individual patient subgroup. Acknowledging these limitations, the data from our large retrospective analysis indicate that patients with MK AML more often have MRD at the time of HCT than those with non-MK AML. While our study confirms higher relapse rates and shorter survival for MK-AML compared to non-MK AML patients, our multivariable analyses suggest that these adverse outcomes are largely accounted for by the presence of other adverse prognostic factors, in particular MRD.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the excellent care provided by the physicians and nurses of the HCT teams, the staff in the Long-Term Follow-up office at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, the Hematopathology Laboratory at the University of Washington, and the patients for participating in our research protocols. This work was supported by grants P01-CA078902, P01-CA018029, and P30-CA015704 from the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health (NCI/NIH).

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Döhner H, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(12): 1136–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Buchner T, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood 2017; 129(4): 424–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimwade D, Walker H, Oliver F, Wheatley K, Harrison C, Harrison G, et al. The importance of diagnostic cytogenetics on outcome in AML: analysis of 1,612 patients entered into the MRC AML 10 trial. The Medical Research Council Adult and Children’s Leukaemia Working Parties. Blood 1998; 92(7): 2322–2333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slovak ML, Kopecky KJ, Cassileth PA, Harrington DH, Theil KS, Mohamed A, et al. Karyotypic analysis predicts outcome of preremission and postremission therapy in adult acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. Blood 2000; 96(13): 4075–4083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrd JC, Mrozek K, Dodge RK, Carroll AJ, Edwards CG, Arthur DC, et al. Pretreatment cytogenetic abnormalities are predictive of induction success, cumulative incidence of relapse, and overall survival in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461). Blood 2002; 100(13): 4325–4336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimwade D, Hills RK, Moorman AV, Walker H, Chatters S, Goldstone AH, et al. Refinement of cytogenetic classification in acute myeloid leukemia: determination of prognostic significance of rare recurring chromosomal abnormalities among 5876 younger adult patients treated in the United Kingdom Medical Research Council trials. Blood 2010; 116(3): 354–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Döhner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Büchner T, Burnett AK, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood 2010; 115(3): 453–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breems DA, Van Putten WLJ, De Greef GE, Van Zelderen-Bhola SL, Gerssen-Schoorl KBJ, Mellink CHM, et al. Monosomal karyotype in acute myeloid leukemia: a better indicator of poor prognosis than a complex karyotype. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26(29): 4791–4797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medeiros BC, Othus M, Fang M, Roulston D, Appelbaum FR. Prognostic impact of monosomal karyotype in young adult and elderly acute myeloid leukemia: the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) experience. Blood 2010; 116(13): 2224–2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oran B, Dolan M, Cao Q, Brunstein C, Warlick E, Weisdorf D. Monosomal karyotype provides better prognostic prediction after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2011; 17(3): 356–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang M, Storer B, Estey E, Othus M, Zhang L, Sandmaier BM, et al. Outcome of patients with acute myeloid leukemia with monosomal karyotype who undergo hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 2011; 118(6): 1490–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kayser S, Zucknick M, Döhner K, Krauter J, Köhne CH, Horst HA, et al. Monosomal karyotype in adult acute myeloid leukemia: prognostic impact and outcome after different treatment strategies. Blood 2012; 119(2): 551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haferlach C, Alpermann T, Schnittger S, Kern W, Chromik J, Schmid C, et al. Prognostic value of monosomal karyotype in comparison to complex aberrant karyotype in acute myeloid leukemia: a study on 824 cases with aberrant karyotype. Blood 2012; 119(9): 2122–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemmati PG, Schulze-Luckow A, Terwey TH, le Coutre P, Vuong LG, Dorken B, et al. Cytogenetic risk grouping by the monosomal karyotype classification is superior in predicting the outcome of acute myeloid leukemia undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation in complete remission. Eur J Haematol 2014; 92(2): 102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo RJ, Atenafu EG, Craddock K, Chang H. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation may alleviate the negative prognostic impact of monosomal and complex karyotypes on patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014; 20(5): 690–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wierzbowska A, Wawrzyniak E, Siemieniuk-Rys M, Kotkowska A, Pluta A, Golos A, et al. Concomitance of monosomal karyotype with at least 5 chromosomal abnormalities is associated with dismal treatment outcome of AML patients with complex karyotype - retrospective analysis of Polish Adult Leukemia Group (PALG). Leuk Lymphoma 2017; 58(4): 889–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strickland SA, Sun Z, Ketterling RP, Cherry AM, Cripe LD, Dewald G, et al. Independent prognostic significance of monosomy 17 and impact of karyotype complexity in monosomal karyotype/complex karyotype acute myeloid leukemia: results from four ECOG-ACRIN prospective therapeutic trials. Leuk Res 2017; 59: 55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon JH, Lee YJ, Seo SK, Han SA, Yoon JS, Ham JY, et al. Outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia patients with monosomal karyotypes. Acta Haematol 2015; 133(4): 327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canaani J, Labopin M, Itälä-Remes M, Blaise D, Socié G, Forcade E, et al. Prognostic significance of recurring chromosomal abnormalities in transplanted patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2019; 33(8): 1944–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baron F, Stevens-Kroef M, Kicinski M, Meloni G, Muus P, Marie JP, et al. Impact of induction regimen and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation on outcome in younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia with a monosomal karyotype. Haematologica 2019; 104(6): 1168–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harada K, Konuma T, Machida S, Mori J, Aoki J, Uchida N, et al. Risk stratification and prognosticators of acute myeloid leukemia with myelodysplasia-related changes in patients undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a retrospective study of the Adult Acute Myeloid Leukemia Working Group of the Japan Society for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2019; 25(9): 1730–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornelissen JJ, Breems D, van Putten WLJ, Gratwohl AA, Passweg JR, Pabst T, et al. Comparative analysis of the value of allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia with monosomal karyotype versus other cytogenetic risk categories. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(17): 2140–2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Araki D, Wood BL, Othus M, Radich JP, Halpern AB, Zhou Y, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: is it time to move toward a minimal residual disease-based definition of complete remission. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(4): 329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y, Othus M, Araki D, Wood BL, Radich JP, Halpern AB, et al. Pre- and post-transplant quantification of measurable (‘minimal’) residual disease via multiparameter flow cytometry in adult acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2016; 30(7): 1456–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hourigan CS, Gale RP, Gormley NJ, Ossenkoppele GJ, Walter RB. Measurable residual disease testing in acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia 2017; 31(7): 1482–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 2016; 127(20): 2391–2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walter RB, Gooley TA, Wood BL, Milano F, Fang M, Sorror ML, et al. Impact of pretransplantation minimal residual disease, as detected by multiparametric flow cytometry, on outcome of myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29(9): 1190–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walter RB, Buckley SA, Pagel JM, Wood BL, Storer BE, Sandmaier BM, et al. Significance of minimal residual disease before myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for AML in first and second complete remission. Blood 2013; 122(10): 1813–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walter RB, Gyurkocza B, Storer BE, Godwin CD, Pagel JM, Buckley SA, et al. Comparison of minimal residual disease as outcome predictor for AML patients in first complete remission undergoing myeloablative or nonmyeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Leukemia 2015; 29(1): 137–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walter RB, Sandmaier BM, Storer BE, Godwin CD, Buckley SA, Pagel JM, et al. Number of courses of induction therapy independently predicts outcome after allogeneic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first morphological remission. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015; 21(2): 373–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffmann AP, Besch AL, Othus M, Morsink LM, Wood BL, Mielcarek M, et al. Early achievement of measurable residual disease (MRD)-negative complete remission as predictor of outcome after myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 2019; in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morsink LM, Bezerra ED, Othus M, Wood BL, Fang M, Sandmaier BM, et al. Comparative analysis of total body irradiation (TBI)-based and non-TBI-based myeloablative conditioning for acute myeloid leukemia in remission with or without measurable residual disease. Leukemia 2019; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simons A, Shaffer LG, Hastings RJ. Cytogenetic nomenclature: changes in the ISCN 2013 compared to the 2009 edition. Cytogenet Genome Res 2013; 141(1): 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buckley SA, Wood BL, Othus M, Hourigan CS, Ustun C, Linden MA, et al. Minimal residual disease prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia: a meta-analysis. Haematologica 2017; 102(5): 865–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rücker FG, Schlenk RF, Bullinger L, Kayser S, Teleanu V, Kett H, et al. TP53 alterations in acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotype correlate with specific copy number alterations, monosomal karyotype, and dismal outcome. Blood 2012; 119(9): 2114–2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaillard JB, Chiesa J, Reboul D, Arnaud A, Brun S, Donadio D, et al. Monosomal karyotype routinely defines a poor prognosis subgroup in acute myeloid leukemia and is frequently associated with TP53 deletion. Leuk Lymphoma 2012; 53(2): 336–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yanada M, Yamamoto Y, Iba S, Okamoto A, Inaguma Y, Tokuda M, et al. TP53 mutations in older adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Int J Hematol 2016; 103(4): 429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leung GMK, Zhang C, Ng NKL, Yang N, Lam SSY, Au CH, et al. Distinct mutation spectrum, clinical outcome and therapeutic responses of typical complex/monosomy karyotype acute myeloid leukemia carrying TP53 mutations. Am J Hematol 2019; 94(6): 650–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.