Abstract

Alterations in DNA damage response (DDR) genes are common in advanced prostate tumors and are associated with unique genomic and clinical features. ATM is a DDR kinase that has a central role in coordinating DNA repair and cell cycle response following DNA damage, and ATM alterations are present in approximately 5% of advanced prostate tumors. Recently, inhibitors of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) have demonstrated activity in advanced prostate tumors harboring DDR gene alterations, particularly in tumors with BRCA1/2 alterations. However, the role of alterations in DDR genes beyond BRCA1/2 in mediating PARP inhibitor sensitivity is poorly understood. To define the role of ATM loss in prostate tumor DDR function and sensitivity to DDR-directed agents, we created a series of ATM-deficient preclinical prostate cancer models and tested the impact of ATM loss on DNA repair function and therapeutic sensitivities. ATM loss altered DDR signaling but did not directly impact homologous recombination (HR) function. Furthermore, ATM loss did not significantly impact sensitivity to PARP inhibition but robustly sensitized to inhibitors of the related DDR kinase ATR. These results have important implications for planned and ongoing prostate cancer clinical trials and suggest that patients with tumor ATM alterations may be more likely to benefit from ATR inhibitor than PARP inhibitor therapy.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, DNA repair, PARP inhibitor, ATM, ATR inhibitor

Introduction

Recent genomic studies have revealed that alterations in DNA damage response (DDR) genes are common in prostate cancer and can arise somatically in the tumor or can be inherited via the germline.[1, 2] Although germline and somatic mutations have been observed across DDR genes and pathways, BRCA2 and ATM are the two most commonly mutated DDR genes in advanced prostate tumors. Several lines of evidence suggest that prostate tumors with DDR gene alterations harbor unique genomic features and can exhibit an aggressive clinical phenotype.

Small molecule inhibitors of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) demonstrate synthetic lethality with tumor homologous recombination (HR) deficiency, and PARP inhibitors are approved for treatment of breast or ovarian cancer patients with mutations in the HR genes BRCA1 or BRCA2. The TOPARP-A trial tested the activity of the PARP inhibitor olaparib in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) patients and showed an overall response rate of 33%.[3] However, the response rate was 88% among patients with loss or mutation of one or more DDR genes, suggesting that DDR gene alterations may be a biomarker for PARP inhibitor sensitivity in mCRPC. Based on these data, the FDA granted breakthrough designation for olaparib in mCRPC patients with a tumor BRCA1/2 or ATM alteration, and the benefit of olaparib over standard therapy was confirmed in recently presented data from the Phase III PROfound trial of olaparib.[4]

Other clinical trials, many of which are still on-going, have also demonstrated activity of PARP inhibitors in mCRPC; however, data from these trials suggest that response rates vary significantly based upon which DDR gene is altered and that the likelihood of clinical benefit is highest in mCRPC patients with BRCA2 alterations. Preliminary results from the TRITON2 trial ( NCT02952534), a Phase II trial investigating the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in men with mCRPC with predicted tumor HR defects, show an overall response rate of 44% among men with BRCA1/2 loss or mutation versus a response rate of 0% for men with ATM or CDK12 loss or mutation.[5] These data led to a recent FDA breakthrough designation for rucaparib in mCRPC patients with a BRCA1/2 alteration. Similarly, in a retrospective review of mCRPC patients with a tumor BRCA2 or ATM alteration treated with olaparib, a PSA decrease of ≥50% was observed in 76% of men with a BRCA2 alteration versus 0% of men with an ATM alteration.[6] Finally, in TOPARP-B, a Phase II trial of olaparib in mCRPC patients with tumor DDR alterations, 24/30 (80%) patients with a tumor BRCA1/2 alteration responded based on radiographic or PSA criteria versus only 2/19 (11%) patients with an ATM alteration.[7] Taken together, these data raise the possibility that only a subset of men with a tumor DDR alteration may benefit from a PARP inhibitor, and specifically, that patients with an ATM alteration may be less likely to benefit than patients with a BRCA1/2 alteration.

In addition to PARP, targeting other DDR proteins – particularly DDR kinases such as ATM, ATR, CHK1/2, DNA-PK, or WEE1 – represents an attractive therapeutic strategy in a variety of tumor contexts. ATR is a DDR kinase that is activated by DNA damage or DNA replication stress and has an important role in preventing excessive genomic instability in tumors. Results from Phase I trials of ATR inhibitors (alone or in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy) have been completed[8, 9], and several on-going Phase II trials aim to characterize the clinical efficacy of these agents and define biomarkers of sensitivity. Preclinical evidence suggests that tumor alterations such as oncogene amplification (which can drive replication stress) or ATM loss may be promising biomarker strategies.

To further investigate the impact of ATM loss on DNA repair function and therapeutic sensitivities, we created and functionally interrogated several ATM-deficient prostate cancer models. We find that ATM loss does not result in HR deficiency and does not significantly sensitize cells to PARP inhibitor treatment but robustly sensitizes cells to ATR inhibition. These data suggest that prostate cancer patients with deleterious ATM alterations may be more likely to benefit from treatment with an ATR inhibitor than a PARP inhibitor.

Materials & Methods

Genomic analysis of clinical data

Copy number alterations for the prostate cancer TCGA cohort (PRAD), including the ATM-containing focal deletions at 11q22.3, were determined using GISTIC2[10], To determine copy number alterations of ATM or other tumors suppressors in mCRPC, we examined whole exome sequencing data from prostate cancer cases previously reported in the SU2C cohort.[11] Tumor purity and ploidy were inferred using FACETs.[12] Allelic copy number was determined using Allelic CapSeg and was adjusted based on the inferred purity and ploidy. To examine ATM gene expression, we evaluated RNA-seq data from prostate tumor/normal pairs from TCGA using Firebrowse tools.[13] Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Cell lines, reagents, and assays

Human prostate cancer lines DU145, 22Rv1, and LNCaP were purchased from ATCC and were authenticated by STR profiling. All cell lines were confirmed to be mycoplasma free. ATM-deficient isogenic lines were created using CRISPR/Cas9 technology (see Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Methods for details). PARP inhibitors (olaparib, rucaparib) were purchased from Selleck Chemicals. The ATR inhibitor VX-970 (M6620) was supplied by Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

Cells were seeded into 24-well plates (2,500–4000 cells/well) and treated with increasing concentrations of drug the following day. Cell viability was assessed after 72–96 hours by adding CellTiter-Glo reagent (Promega) and measuring luminescence using a plate reader (BioTek). For clonogenic survival assays, cells were seeded in 6-well plates (500–4000 cells/well) in triplicate. Cells were treated with drug 16 to 18 hours after plating and were allowed to grow for 14 days. Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Results

ATM Loss Is Enriched in Advanced Prostate Cancer

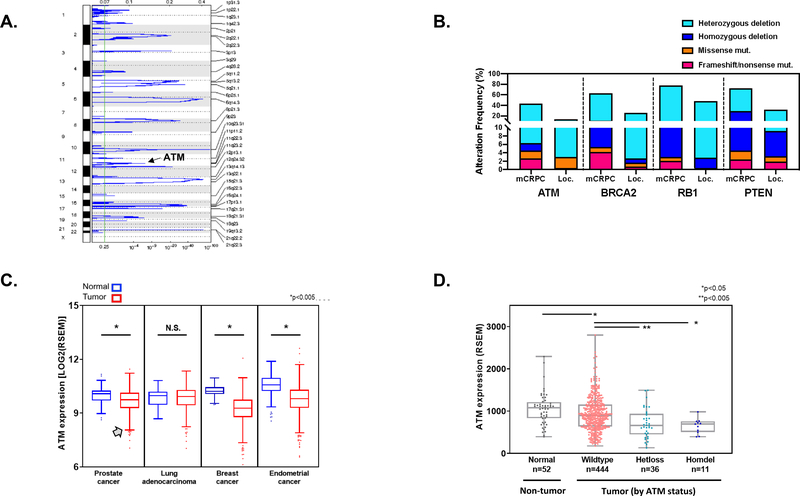

In order to characterize the frequency of ATM loss in prostate cancer, we performed copy-number analysis to identify genomic regions that are frequently deleted in prostate tumors. Across the prostate cancer TCGA cohort (PRAD; n=492), we identified several genomic regions harboring focal deletions (Fig. 1A). These deletion peaks include genes that are known to be frequently lost in prostate tumors such as PTEN and RB1. In addition, a focal genomic region on chromosome 11q22.3 that includes the ATM gene was significantly deleted across the cohort (q=0.00026). We also compared the frequency of ATM deletions in primary prostate tumors versus metastatic tumors following adjustment for tumor purity and ploidy.[11] Similar to other frequently altered tumor suppressor genes such as BRCA2, RB1, and PTEN, heterozygous and homozygous ATM loss as well as ATM frameshift and nonsense mutations were enriched in mCRPC compared to primary tumors (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1: ATM loss in prostate cancer.

A. Copy-number analysis of TCGA prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD) cohort shows that a segment of chromosome 11q22.3 which includes the ATM gene is focally lost (q=2.6e-4). B. Heterozygous loss, homozygous loss, and frameshift/nonsense mutations in ATM and other tumor suppressor genes are more frequent in mCRPC than in primary prostate tumors. C. ATM gene expression in normal versus tumor tissue across several TCGA tumor types shows a subset of tumors with low ATM transcript levels (denoted by gray arrow). D. ATM gene expression is decreased in prostate tumors compared to normal prostate tissue, and tumors with heterozygous or homozygous ATM deletion have significantly lower ATM levels than tumors without ATM deletion. mCRPC, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Loc., localized prostate cancer.

We also analyzed ATM gene expression in prostate cancer and several other tumor types in which ATM loss occurs. In prostate cancer and several of the other tumor types, ATM gene expression was significantly lower in tumors than in normal prostate tissue, and in each case, there were a subset of tumors with very low ATM gene expression (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, when stratified by ATM genomic status, prostate tumors with heterozygous or homozygous deletion of the ATM gene had significantly lower ATM gene transcript levels than tumors without ATM loss (Fig. 1D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that ATM loss is a recurrent event in prostate cancer, is enriched in mCRPC compared to localized tumors, and is accompanied by decreased ATM gene expression.

ATM Loss Alters DDR Signaling but Does Not Directly Impair HR Function

To determine the impact of ATM loss on DDR signaling and therapeutic sensitivities, we used CRISPR/Cas9 and siRNA to create a series of ATM-deficient prostate cancer cell line models that varied in androgen receptor (AR) status, sensitivity to AR inhibition, and TP53 status. For each CRISPR/Cas9-edited cell line, plasmids encoding the Cas9 nuclease and an ATM-targeting short guide RNA (sgRNA) were transduced and the cells were then subjected to antibiotic selection followed by single cell cloning and expansion. ATM loss in the recovered clonal populations was confirmed by immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2A).

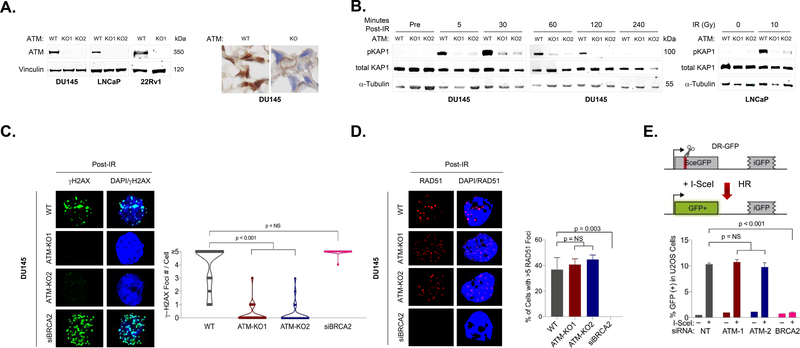

Figure 2: ATM loss alters DDR-mediated signaling but does not directly impair homologous recombination.

A. Immunoblot and immunohistochemical analysis confirming loss of ATM protein expression in CRISPR/Cas9-edited prostate cancer cell lines. B. Immunoblots showing phosphorylated and total levels of KAP1 following ionizing radiation (IR). ATM deletion leads to a marked decrease in IR-induced KAP1 phosphorylation, consistent with loss of ATM-mediated DDR signaling. C. Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis shows that ATM deletion results in significant decrease in IR-induced γ-H2AX foci in DU145 cells. D. ATM deletion does not impact formation of Rad51 foci following IR, whereas BRCA2 depletion leads to loss of Rad51 foci. E. ATM depletion does not impact HR efficiency as measured by the DR-GFP reporter assay, whereas BRCA2 depletion nearly completely abolishes cellular HR.

We first tested the impact of ATM loss on DDR signaling following DNA damage in our prostate cancer models. KAP1 (encoded by TRIM28) is a primary target of ATM that is phosphorylated following DNA damage, and we found that time-dependent KAP1 phosphorylation was dramatically diminished across ATM-deleted prostate cell lines (Fig. 2B). ATM is also one of the DDR kinases that can phosphorylate histone H2AX, an important early step in coordination of repair activities at sites of DNA double-strand breaks. We observed time- and dose-dependent impact of ATM loss on phospho-H2AX (γH2AX) foci formation across models, with significant abrogation of IR-induced γH2AX foci in ATM-deleted DU145 cells but less impact in ATM-deleted LNCaP cells (Fig. 2C; Supplementary Figures 1, 2). Together, these results demonstrate that ATM loss impacts DDR signaling in a cell-context specific manner.

We next tested the impact of ATM loss on HR using two complementary approaches. Rad51 nucleofilaments assemble at processed DSBs and catalyze strand invasion to promote HR; therefore, formation of Rad51 filaments following DNA damage is a feature of HR proficiency. Both ATM-wild type (WT) and ATM-deleted prostate cancer cells form Rad51 foci following IR, suggesting that HR function remains intact despite ATM loss (Fig. 2D; Supplementary Figure 1). Conversely, no Rad51 foci form in BRCA2-depleted prostate cancer cells, consistent with the central role of BRCA2 in coordinating DSB repair via HR.

We also directly tested the effect of ATM loss on HR using the DR‐GFP reporter assay.[14] The DR-GFP assay uses a restriction endonuclease to create a DSB in one of two defective copies of the GFP gene arranged in direct repeat on a reporter cassette in an engineered U2OS cell line. HR-mediated repair of the DSB using the second defective copy of the GFP as a template creates a GFP open reading frame, allowing HR to be quantified by fluorescence (Fig. 2E). Depleting ATM with two different siRNAs had no effect on HR efficiency whereas depleting BRCA2 significantly inhibited HR activity. Together, these data suggest that ATM loss alters DDR signaling following DNA damage, but unlike BRCA2 loss, does not directly abolish HR function in prostate cancer cells.

ATM Loss Confers Sensitivity to Radiation but has Minimal Impact on Sensitivity to Carboplatin or PARP Inhibition

Given the observed effect on DDR signaling, we tested the impact of ATM loss on sensitivity to DNA damaging agents commonly used in prostate cancer. We observed a significant impact of ATM loss on sensitivity to ionizing radiation (IR) across cell lines, but minimal impact on carboplatin sensitivity (Fig. 3A; Supplementary Figure 3). This result is consistent with ATM’s known role in response to IR-induced DNA breaks, although the magnitude of effect is lower than reported in some cell line contexts.[15]

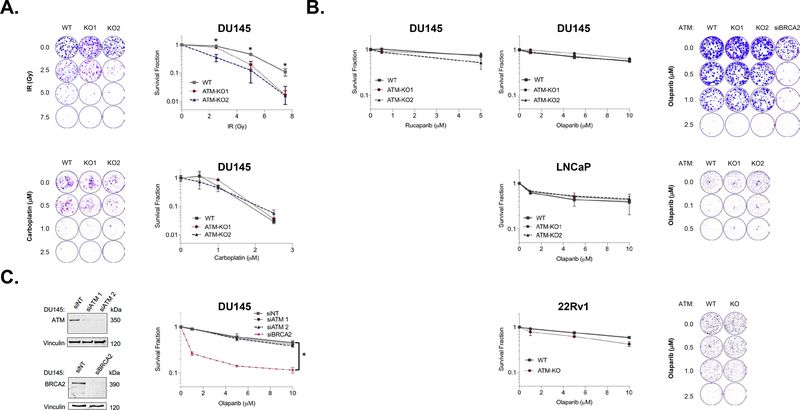

Figure 3: ATM Loss Sensitizes to Radiation but not Carboplatin or PARP Inhibition.

A. ATM loss significantly increases sensitivity to ionizing radiation (IR), but does not impact sensitivity to carboplatin. B. Deletion of ATM does not impact sensitivity to PARP inhibition across prostate cell line models as measured by 3–4 day cell viability (left) or 10–14 day clonogenic survival (right). C. ATM depletion by siRNA also does not increase PARP inhibitor sensitivity whereas BRCA2 depletion significantly increases sensitivity. Data are plotted as mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Astericks (*) denote p<0.05.

Published studies have shown that mCRPC patients with a tumor DDR gene alteration respond to single agent PARP inhibitor.[3] However, preliminary analyses of on-going PARP inhibitor trials suggest that the majority of benefit may be restricted to patients with tumor BRCA1/2 alterations while patients with tumor ATM alterations are less likely to respond. We did not observe significant differences in sensitivity to PARP inhibition across our ATM-WT versus ATM-deleted prostate cancer models in 3–4 day cell viability or 10–14 day clonogenic survival assays (Fig. 3B). Similarly, no significant difference in olaparib sensitivity was noted when ATM was depleted by siRNA prior to PARP inhibitor treatment, whereas BRCA2 depletion robustly sensitized to olaparib treatment (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that ATM loss alone is insufficient to consistently drive PARP inhibitor sensitivity across prostate tumor contexts.

ATM Loss Sensitizes Prostate Cancer Cells to ATR Inhibition

ATR is a DDR kinase that is activated by DNA damage or replication stress, and inhibitors of ATR are under investigation in numerous clinical trials alone or in combination with cytotoxic agents. Because ATR has a central role in coordinating response to replication stress, tumor features such as MYC or CCNE amplification, which have been associated with increased DNA replication stress, are being investigated as biomarkers of ATR inhibitor sensitivity. In addition, given the related functions of ATM and ATR in the DNA damage response, ATM deficiency has also been nominated as a potential biomarker of sensitivity to ATR inhibition.[9]

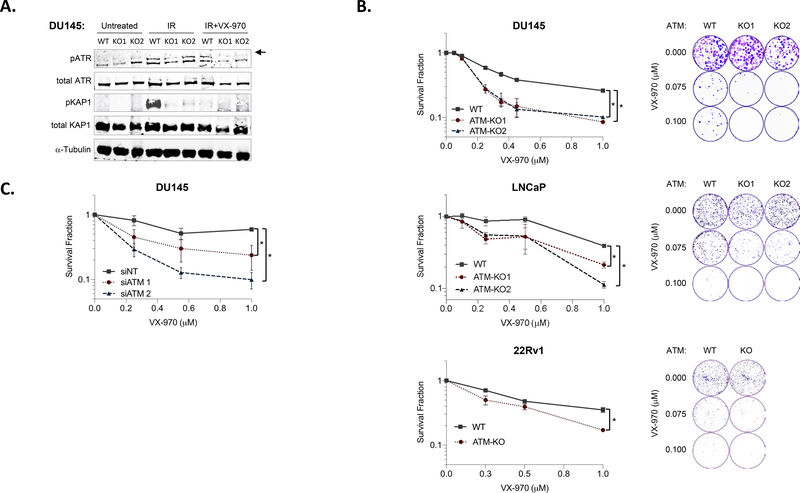

We hypothesized that ATM loss would increase ATR inhibitor sensitivity in our prostate cancer models. We first tested the impact of the ATR inhibitor M6620 (VX-970) on DDR signaling and found that VX-970 inhibited IR-induced ATR auto-phosphorylation and ATR-mediated KAP1 phosphorylation (Fig. 4A). We next treated ATM-WT and ATM-deleted cell lines with the ATR inhibitor M6620 (VX-970) and observed significantly increased sensitivity to ATR inhibition across ATM-deleted models compared to ATM-WT models (Fig. 4B). Similarly, ATM depletion by siRNA was sufficient to drive sensitivity to ATR inhibition (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these data suggest that ATM loss is a potential biomarker for ATR inhibitor sensitivity in prostate cancer and that ATR inhibition may be a more promising therapeutic strategy than PARP inhibition for the subset of prostate cancer patients with tumor ATM loss.

Figure 4. ATM Loss Confers Sensitivity to ATR Inhibition.

A. Immunoblot analysis reveals that the ATR inhibitor M6620 (VX-970) inhibits IR-induced ATR auto-phosphorylation (upper band, denoted by arrow) and ATR-mediated KAP1 phosphorylation in prostate cancer cell lines. B. ATM deletion results in increased sensitivity to the ATR inhibitor VX-970 across prostate cancer cell line models as measured by 3–4 day cell viability (left) or 10–14 day clonogenic survival (right). C. ATM depletion by siRNA also increases sensitivity to ATR inhibition. Data are plotted as mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Astericks (*) denote p<0.05. IR, ionizing radiation.

Discussion

Several studies in the past five years have uncovered an unexpectedly high rate of germline and somatic DDR pathway alterations in advanced prostate cancer.[1, 2, 16, 17] These data have important implications for screening and risk stratification as well as treatment. Importantly, prospective data from clinical trials now shows that DDR pathway alterations – particularly BRCA1/2 alterations – are associated with increased sensitivity to PARP inhibition, and these data have led to FDA breakthrough designation for PARP inhibitors for advanced prostate tumors harboring BRCA1/2 or ATM alterations.

Our results indicate that the ATM gene is completely lost in approximately 2% of advanced prostate tumors, and other genomic alterations including frameshift or missense mutations occur in an additional subset of cases. ATM has been included in many DDR gene panels used to select patients for enrollment on completed and on-going prostate cancer PARP inhibitor trials. However, ATM has a role in coordinating DNA damage response and repair that is distinct from upstream proteins such as BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2, which directly participate in repair events at the DSB. Indeed, prostate tumors with ATM alterations lack the mutational signature of HR deficiency that is present in tumors with BRCA1/2 alterations[17], suggesting that ATM alterations have distinct impacts on DNA repair and genomic stability compared to BRCA1/2 alterations.

Based on the predicted differential impacts on DNA repair as well as clinical evidence suggesting lower PARP inhibitor response rates in patients with tumor ATM alterations compared to patients with tumor BRCA1/2 alterations, we sought to investigate the impact of ATM loss on DDR signaling and therapeutic sensitivities in preclinical prostate cancer models. To this end, we created a series of ATM-deficient models using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene deletion and siRNA-mediated gene depletion across several prostate cancer cell line models representing different genomic contexts and disease states.

Across the ATM-deficient models, we consistently observed abrogation of ATM-mediated DDR signaling but minimal impact on sensitivity to PARP inhibitors. Increased PARP inhibitor sensitivity has been noted in other preclinical ATM-deficient settings including mouse models of pancreatic and lung adenocarcinomas.[18, 19] Similarly, some ATM-deficient human cancer cell lines have been reported to have increased PARP inhibitor sensitivity, with the degree of sensitivity dependent upon cell line and genomic context.[20–23] The clinical activity of PARP inhibitors in ATM-deleted tumors – including other HR-deficient tumor types such as breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer – has not yet been clearly defined. It is likely that the impact of ATM loss on PARP inhibitor sensitivity is context dependent both within and across tumor types, and this may explain the variation in PARP inhibitor response rate among ATM-altered tumors in reported clinical experiences.[3, 5–7] Furthermore, genetic and pharmacologic evidence suggests that ATM kinase inactivation confers a distinct phenotype from complete ATM loss in preclinical models[24, 25]; therefore, co-targeting PARP and ATM may remain a viable therapeutic strategy in prostate cancer even though ATM gene loss does not appear to significantly increase PARP inhibitor sensitivity.

In addition to investigation as a potential biomarker of PARP inhibitor sensitivity, tumor ATM alterations have also been explored as a biomarker of sensitivity to small molecule inhibitors of the related DDR kinase ATR based on preclinical work demonstrating a potential synthetic lethal interaction.[26, 27] Several ATR inhibitors are being investigated in early-phase clinical trials, and ATM alterations have emerged as a predictive biomarker of ATR inhibitor sensitivity.[8, 9] We found that ATM loss or depletion robustly sensitized to ATR inhibition across our models, supporting a role for ATM loss as a biomarker of ATR inhibitor sensitivity in prostate cancer. Additional studies are needed to define the impact of distinct tumor ATM alterations (deletions, truncating mutations, and missense mutations) on ATR inhibitor sensitivity, identify other tumor genomic alterations that may modulate ATR inhibitor sensitivity (in the presence or absence of ATM loss), and define the interaction among tumor AR status, AR-directed therapies, and sensitivity to ATR inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding: DF/HCC Prostate SPORE (KWM), PCF Young Investigator Award (KWM), 5K08CA219504 (KWM), NCI PCF-V Foundation Challenge Award (EVM), U01 CA233100 (EVM), U01 CA176058 (WCH)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest (COI): None of these activities reported below are directly related to the work in this manuscript. Authors not listed below declare no potential COIs.

References

- 1.Pritchard CC, et al. , Inherited DNA-Repair Gene Mutations in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2016. 375(5): p. 443–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson D, et al. , Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell, 2015. 161(5): p. 1215–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mateo J, et al. , DNA-Repair Defects and Olaparib in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2015. 373(18): p. 1697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hussain M, et al. , PROfound: Phase III study of olaparib versus enzalutamide or abiraterone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) with homologous reocmbination repair (HRR) gene alterations. Annals of Oncology, 2019. 30 (suppl_5): v851–v934. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abida W, et al. , Preliminary results from TRITON2: A phase II study of rucaparib in patients (pts) with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) associated with homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene alterations. Annals of Oncology, 2018. 29 (suppl_8): viii271–viii302. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall CH, et al. , Differential Response to Olaparib Treatment Among Men with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer Harboring BRCA1 or BRCA2 Versus ATM Mutations. Eur Urol, 2019. 76(4): p. 452–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mateo J, et al. , TOPARP-B: A phase II randomized trial of the poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor olaparib for metastatic castration resistant prostate cancers (mCRPC) with DNA damage repair (DDR) alterations. J Clin Oncol, 2019. 37: p. 5005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas A, et al. , Phase I Study of ATR Inhibitor M6620 in Combination With Topotecan in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors. J Clin Oncol, 2018. 36(16): p. 1594–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Bono JS, et al. , First-in-human trial of the oral ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR) inhibitor BAY 1895344 in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol, 2019. 37: p. 3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harvard BIOMA, Broad Institute TCGA Genome Data Analysis Center (2016): SNP6 Copy number analysis (GISTIC2). 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armenia J, et al. , The long tail of oncogenic drivers in prostate cancer. Nat Genet, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen R and Seshan VE, FACETS: allele-specific copy number and clonal heterogeneity analysis tool for high-throughput DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res, 2016. 44(16): p. e131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng M, et al. , FirebrowseR: an R client to the Broad Institute’s Firehose Pipeline. Database, 2017: p. 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pierce AJ and Jasin M, Measuring recombination proficiency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol Biol, 2005. 291: p. 373–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuhne M, et al. , A double-strand break repair defect in ATM-deficient cells contributes to radiosensitivity. Cancer Res, 2004. 64(2): p. 500–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armenia J, et al. , The long tail of oncogenic drivers in prostate cancer. Nat Genet, 2018. 50(5): p. 645–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quigley DA, et al. , Genomic Hallmarks and Structural Variation in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Cell, 2018. 175(3): p. 889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perkhofer L, et al. , ATM Deficiency Generating Genomic Instability Sensitizes Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Cells to Therapy-Induced DNA Damage. Cancer Res, 2017. 77(20): p. 5576–5590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmitt A, et al. , ATM Deficiency Is Associated with Sensitivity to PARP1- and ATR Inhibitors in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res, 2017. 77(11): p. 3040–3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubota E, et al. , Low ATM protein expression and depletion of p53 correlates with olaparib sensitivity in gastric cancer cell lines. Cell Cycle, 2014. 13(13): p. 2129–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang C, et al. , ATM-Deficient Colorectal Cancer Cells Are Sensitive to the PARP Inhibitor Olaparib. Transl Oncol, 2017. 10(2): p. 190–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weston VJ, et al. , The PARP inhibitor olaparib induces significant killing of ATM-deficient lymphoid tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Blood, 2010. 116(22): p. 4578–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williamson CT, et al. , Enhanced cytotoxicity of PARP inhibition in mantle cell lymphoma harbouring mutations in both ATM and p53. EMBO Mol Med, 2012. 4(6): p. 515–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kass EM, et al. , Double-strand break repair by homologous recombination in primary mouse somatic cells requires BRCA1 but not the ATM kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013. 110(14): p. 5564–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamoto K, et al. , Kinase-dead ATM protein is highly oncogenic and can be preferentially targeted by Topo-isomerase I inhibitors. Elife, 2016. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menezes DL, et al. , A synthetic lethal screen reveals enhanced sensitivity to ATR inhibitor treatment in mantle cell lymphoma with ATM loss-of-function. Mol Cancer Res, 2015. 13(1): p. 120–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwok M, et al. , ATR inhibition induces synthetic lethality and overcomes chemoresistance in TP53- or ATM-defective chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Blood, 2016. 127(5): p. 582–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.