Abstract

Cancer cells exploit the unfolded protein response (UPR) to mitigate endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress caused by cellular oncogene activation and a hostile tumor microenvironment (TME). The key UPR sensor IRE1α resides in the ER and deploys a cytoplasmic kinase-endoribonuclease module to activate the transcription factor XBP1s, which facilitates ER-mediated protein folding. Studies of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)—a highly aggressive malignancy with a dismal post-treatment prognosis—implicate XBP1s in promoting tumor vascularization and progression. However, it remains unknown whether IRE1α adapts the ER in TNBC cells and modulates their TME, and whether IRE1α inhibition can enhance anti-angiogenic therapy—previously found to be ineffective in TNBC patients. To gauge IRE1α function, we defined an XBP1s-dependent gene signature, which revealed significant IRE1α pathway activation in multiple solid cancers, including TNBC. IRE1α knockout in TNBC cells markedly reversed substantial ultrastructural expansion of the ER within these cells upon growth in vivo. IRE1α disruption also led to significant remodeling of the cellular TME, increasing pericyte numbers while decreasing cancer-associated fibroblasts and myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Pharmacological IRE1α kinase inhibition strongly attenuated growth of cell-line-based and patient-derived TNBC xenografts in mice and synergized with anti-VEGF-A treatment to cause tumor stasis or regression. Thus, TNBC cells critically rely on IRE1α to adapt their ER to in vivo stress and to adjust the TME to facilitate malignant growth. TNBC reliance on IRE1α is an important vulnerability that can be uniquely exploited in combination with anti-angiogenic therapy as a promising new biologic approach to combat this lethal disease.

Keywords: Breast cancer, endoplasmic reticulum stress, unfolded protein response, inositol requiring enzyme 1, kinase inhibitors, anti-VEGF-A, CAF

Introduction

Amongst the main breast cancer subtypes, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) accounts for 15-20% of total incidence, and holds the most urgent need for effective therapy. It is defined immunohistochemically by absent expression of 3 key markers: estrogen receptor α (ERα), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2, or ERBB2/NEU). TNBC is an early-onset, highly aggressive malignancy, with dismal prognosis post standard-of-care chemotherapy (1,2).

The unfolded protein response (UPR) is an intracellular sensing-signaling network that helps cells mitigate stress-driven perturbations to protein biosynthetic 3D folding within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (3–5). The mammalian UPR comprises a triad of ER-membrane-resident sensors: IRE1α (inositol-requiring enzyme 1α), PERK (protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase), and ATF6 (activating transcription factor-6). Upon direct or indirect detection of unfolded proteins through an ER-lumenal domain, each UPR sensor engages its own cytoplasmic moiety to adjust the ER’s capacity to fold proteins and synthesize membranes, thereby helping to alleviate ER stress. If mitigation fails, the UPR induces apoptosis (6). IRE1α contains a cytosolic serine/threonine kinase domain, which controls activation of a tandem endoribonuclease (RNase) moiety (7,8). Under ER stress, IRE1α dimerizes and trans-autophosphorylates, thereby activating its RNase module (8–11). The RNase excises 26 nucleotides from the mRNA encoding unspliced X-box protein 1 (XBP1u), causing a frame shift after RtcB-mediated ligation of the excised exons, to produce an mRNA encoding spliced XBP1 (XBP1s) (3,4,12,13). XBP1s is a transcription factor that stimulates multiple genes with adaptive and cytoprotective functions to facilitate ER-stress mitigation (14–16). In addition to promoting XBP1 mRNA splicing, the IRE1α RNase degrades ER-targeted mRNAs—a process termed regulated IRE1α-dependent decay, or RIDD—to abate translation (17,18), suppress apoptosis (19,20), and augment protective autophagy (21).

During cancer initiation, progression, and metastasis, tumor cells face various types of intrinsic and extrinsic stress, caused by activation of oncogenes and by metabolically restrictive tumor microenvironments (TMEs). Such stress conditions can overburden or perturb the ER’s protein-folding functions, driving certain types of cancer cells to activate the UPR as a means of sustaining malignant growth while retaining viability (22–24). In ERα+ breast cancer, the UPR in general, and XBP1s in particular, contribute to acquired resistance against anti-endocrine therapy (25). TNBC also coopts the UPR, as shown by seminal published work implicating XBP1s in conjunction with HIF1α in driving TNBC tumor angiogenesis and progression under hypoxia (26). More recent studies also have linked the IRE1α-XBP1s axis to the oncogenic transcription factor MYC—a potent driver of proliferation and protein synthesis (27)—in TNBC (28), prostate cancer (29), and B-cell lymphoma (30). Pharmacologic inhibition of IRE1α via its RNase domain markedly augmented the effectiveness of taxane chemotherapy in cell-line-based or patient-derived xenograft TNBC models (28,31). Analysis by transmission electron microscopy revealed a highly dilated ER in TNBC cell lines grown in vitro, suggesting volumetric ER expansion and adaptation to stress (26). Similar changes were observed in MYC expressing B-cell lymphomas (30).

The breast cancer TME has a complex cellular character, comprising both malignant and nonmalignant cells. Of the latter category, endothelial cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) play key roles in supporting the development and progression of breast cancer (22,32,33). Higher micro-vascular density generally correlates with greater tumor burden, more advanced grade, more frequent lymph-node metastasis, and poorer prognosis (34,35). Tumor vascularization is more extensive in TNBC relative to other breast cancers (34,36), suggesting greater dependency on angiogenesis. Cancer cells actively promote tumor vascularization by secreting several proangiogenic growth factors, amongst which vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) plays a prominent role (35). Breast cancer clinical trials have been performed with bevacizumab—a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting VEGF-A, which is FDA-approved for certain other cancer indications—in combination with different chemotherapy regimens. Disappointingly, these trials failed to demonstrate an overall survival benefit. Nevertheless, subgroup analysis revealed a considerable improvement of overall response rates and progression-free survival, particularly in TNBC (34). Therefore, the treatment of TNBC may ultimately benefit from complementation of anti-angiogenic therapy with mechanistically distinct novel strategies. Previous work established a biological link between XBP1s, hypoxia, and tumor angiogenesis (37,38). Furthermore, XBP1s expression was shown to enhance VEGF-A production and vascularization in TNBC tumor models and to correlate with worse prognosis in TNBC patients (26,28,39).

CAFs are the most abundant stromal cell type in the TME and play a central role in promoting breast cancer tumor vascularization, growth, invasiveness, and treatment resistance (33). Indeed, CAFs correlate with a more aggressive breast cancer phenotype and poorer patient survival (40). Similarly, MDSCs exert not only immunosuppressive functions but also directly stimulate tumor growth, tumor vascularization and metastasis (32). Accordingly, novel therapeutic strategies to diminish the abundance or activity of CAFs and MDSCs in the TME are potentially important.

Despite significant advances in understanding of the role of the IRE1α pathway in TNBC, several key mechanistic and therapeutic questions remain: (1) How important is IRE1α for ER adaptation in malignant TNBC cells? (2) Given its function in facilitating protein folding and secretion, does IRE1α modulate the cellular composition of the TME? (3) Does pharmacological inhibition of IRE1α via its kinase domain, rather than RNase moiety, inhibit TNBC tumor growth? (4) Can IRE1α inhibition complement the insufficient efficacy of anti-angiogenic therapy in TNBC?

Our results have mechanistic as well as therapeutic potential implications for the IRE1α pathway in TNBC. Mechanistically, we show that IRE1α knockout fully reverses the marked ultrastructural adaptation of the ER in TNBC cells growing in vivo. Furthermore, IRE1α disruption substantially remodels the TME in TNBC by increasing pericyte levels and promoting vascular normalization, while decreasing CAFs and MDSCs. Therapeutically, pharmacologic inhibition of IRE1α through its kinase module substantially attenuates tumor growth in models of both cell-line-based and patient-derived TNBC xenografts in mice. Importantly, IRE1α inhibition cooperates with anti-VEGF-A antibody treatment to achieve frequent TNBC tumor regression. Our results open promising new avenues to investigate these two evidently complementary therapeutic approaches to develop more effective biological treatments for TNBC.

Materials and Methods

Detailed methods are provided in Supplementary data.

Cell culture and experimental reagents

All cell lines were obtained or generated from an internal repository maintained at Genentech. Short tandem repeat (STR) profiles were determined using the Promega PowerPlex 16 System, and compared to external STR profiles of cell lines to determine cell line ancestry. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) profiles were performed each time new stocks were expanded for cryopreservation. Cell line identity was verified by high-throughput SNP profiling using Fluidigm multiplexed assays. SNPs were selected based on minor allele frequency and presence on commercial genotyping platforms. SNP profiles were compared to SNP calls from available internal and external data (when available) to confirm ancestry.

Cell lines were tested to ensure they were mycoplasma free prior to and after cells were cryopreserved. Two methods were used to avoid false positive/negative results: Lonza Mycoalert and Stratagene Mycosensor. In addition, cell growth rates and morphology were monitored for any batch-to-batch changes. All cell lines were cultured in RPMI1640 media supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma), 2 mM glutaMAX (Gibco) and 100 U/ml penicillin plus 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco) over 2 to 3 passages before use. Thapsigargin (Sigma) was used at a concentration of 100 nM.

Monoclonal antibody generation

A recombinant protein encoding the kinase and RNase domains of human IRE1α (amino acids 547 – 977) was generated via a baculovirus expression system in SF9 cells and purified to homogeneity using a TEV-protease cleavable His6 tag. Mice were immunized using standard protocols and monoclonal antibodies were screened by western blot against recombinant purified IRE1α lumenal and cytoplasmic domain proteins or lysates from MDA-MB-231 cells expressing wild type IRE1 or harboring CRISPR/Cas9 knockout (KO) of IRE1α. A mouse IgG2a monoclonal antibody that specifically and selectively detected the human IRE1α (GN35-18) was thus isolated and cloned.

ER16 signature scores

RNA-sequencing (seq) counts for genes of the ER16 signature were obtained from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), and normalized by multiplying the counts in each library by the size Factor computed from DESeq2 package in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria). For each gene, a Z-score was computed by subtracting its mean and dividing by its standard deviation over all samples in the dataset. A signature score for ER16 was computed by taking the mean of these Z-scores over all 16 genes in the signature. Analysis of cell lines was performed in a similar fashion, except using RNA-seq data from Genentech’s centralized cell bank (gCell) dataset (https://www.gene.com). Correlations of each gene against the ER16 score were computed as the Pearson correlation coefficient using the cor function in R. All plots of ER16 signature scores utilize an exponential scale to show values from 0 to infinity, with the mean score over all samples indicated by a value of 1.

Annotation of breast cancer samples in TCGA was obtained from the Genomic Data Commons portal at https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/legacy-archive/files/735bc5ff-86d1-421a-8693-6e6f92055563. Breast cancer samples were classified as HER2-positive if the field her2_status_by_ihc was “Positive”; as ER/PR-positive if the field her2_status_by_ihc was “Negative” and either er_status_by_ihc or pr_status_by_ihc was “Positive”; and as triple-negative if all of the above-mentioned fields were “Negative”.

For statistical analysis, a Student’s t-test was performed between Z-scores on all pairs of indications of TCGA that had both a cancer and normal subtype, with each cancer subtype compared against its corresponding normal. Breast cancer subtypes, as described previously, were considered beyond the annotations from TCGA. P-values were computed as one-sided with the null hypothesis that the normal subtype had greater expression than the cancer subtype. False discovery rates (FDR) were computed over all p-values using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure using the qvalue function from the qvalue package in R with pi0 set to 1.

Subcutaneous xenograft growth and efficacy studies

In all in vivo studies, 5x106 MDA-MB-231 or 2x106 HCC1806 tumor cells and their corresponding KO clones or shRNA expressing cells were suspended in HBSS, admixed with 50% Matrigel (Corning) to a final volume of 100 μl, and injected subcutaneously in the right flank of 6 to 8-week old female C.B-17 SCID (MDA-MB-231 model) or SCID.bg (HCC1806 model) mice (Charles River Laboratories).

For efficacy studies, tumors were monitored until they reached a mean tumor volume of approximately 150 mm3 (MDA-MB-231), or 150-400 mm3 (HCC1806). To test efficacy of doxycycline-inducible shRNA in HCC1806 tumor xenografts, animals were randomized into the following treatment groups: (i) 5% sucrose water (provided in drinking water, changed weekly); or (ii) doxycycline (0.5 mg/ml, dissolved in 5% sucrose water, changed 3x/ week).

To assess efficacy of compound 18 in combination with anti-VEGF-A, animals were randomized into one of the following treatment groups: (i) vehicle control (35% PEG400 and 10% EtOH in water, 100 μL total, IP, QD) and anti-ragweed 1428 (2 mg/kg, 100 μL, IP, twice per week (BIW)); (ii) compound 18 ((41,42) 30 mg/kg, 100 μL, IP, QD) and anti-ragweed 1428; (iii) anti-VEGF-A (B20-4.1.1 (43), 2 mg/kg, 100 μL, IP, BIW) and vehicle control; compound 18 ((41,42) 30 mg/kg, 100 μL, IP, QD) and anti-ragweed 1428; or (iv) compound 18 and anti-VEGF-A.

To analyze tumor xenograft vessel leakiness, 200 μl of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran (15 mg/ml in PBS, MW 2,000,000; Sigma-Aldrich) was injected into the tail vein of mice 2 hrs before animals were sacrificed. Xenografts were excised and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for storage and further processing.

Orthotopic mammary fat pad PDx tumor growth and efficacy study

The tumor graft line HCI-004 was used, which is a patient-derived xenograft (PDx) model derived from a primary TNBC of an infiltrating ductal carcinoma (44). Tumor pieces were surgically transplanted into the right #2/3 mammary fat pad of female 6 to 7-week old NOD SCID mice (Charles River Laboratories). When donor mice had tumors of around 1500 mm3, animals were humanely euthanized as outlined below and size-matched xenografts of two mice aseptically collected. Xenografts were rinsed in HBSS, sectioned into 2 mm3 pieces and then surgically engrafted as described above in an experimental cohort of female NOD SCID mice. Tumors were monitored until they reached a mean volume of approximately 150 mm3, and to test the efficacy of compound 18, anti-VEGF-A, or the combination thereof, animals were randomized into treatment groups as outlined above (n=15/ group).

In all in vivo studies, tumor size and body weight were measured twice per week. Subcutaneous and mammary fat pad tumor volumes were measured in two dimensions (length and width) using Ultra Cal-IV calipers (model 54 – 10 – 111; Fred V. Fowler Co.). The tumor volume was calculated using the following formula: tumor size (mm3) = (longer measurement × shorter measurement2) × 0.5. Animal body weights were measured using an Adventurer Pro AV812 scale (Ohaus Corporation). Percent weight change was calculated using the following formula: group percent weight change = [(new weight – initial weight)/initial weight] × 100. To analyze repeated measurements of tumor volumes from the same animals over time, a generalized additive mixed modeling approach was used (45). This approach addresses both repeated measurements and modest dropouts before the end of study. Cubic regression splines were used to fit a nonlinear profile to the time courses of log2 tumor volume in each group. Fitting was done via a linear mixed-effects model, using the package “nlme” (version 3.1-108) in R version 2.15.2 (R Development Core Team 2008; R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria). Tumor growth inhibition (TGI) as a percentage of vehicle was calculated as the percent difference between the daily average area under the tumor volume-time curve (AUC) of treatment and control group fits on the original untransformed scale over the same time period using the following formula: %TGI = (1-[(AUC/Day)Treatment ÷ (AUC/Day)Vehicle]) × 100. All AUC calculations were baseline-adjusted to the initial tumor burden on day 0. As such, positive values indicate an anti-tumor effect (100% TGI equals tumor stasis and TGI values >100% denote tumor regression). Values in parenthesis indicate the upper and lower boundaries of the 95% confidence interval for the percent difference based on the fitted model and variability measures of the data.

All procedures were approved by and conformed to the guidelines and principles set by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Genentech and were carried out in an Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-accredited facility.

When mice reached endpoint criteria or on the last treatment day, mice were euthanized and xenografts harvested for further analysis. Animals in all studies were humanely euthanized according to the following criteria: clinical signs of persistent distress or pain, significant body-weight loss (>20%), tumor size exceeding 2500 mm3, or when tumors became ulcerated. Maximum tumor size permitted by the IACUC is 3000 mm3 and in none of the experiments was this limit exceeded.

Statistics

All values are represented as arithmetic mean ± standard deviation with at least three independent biological or technical replicates experiments if not otherwise indicated in the figure legends. Statistical analysis of the results was performed by unpaired, two-tailed t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by an appropriate post-hoc analysis, including Bonferroni correction to compensate for multiple comparisons. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant, and denoted by * = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01, *** = p<0.001. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). For statistical analysis of ER16 scores refer to the corresponding section in Supplementary data.

Results

Close sequence similarity between the two splice variants of XBP1 mRNA makes their discrimination within standard RNA-seq datasets relatively difficult. Therefore, to gauge more precisely activation of the IRE1α-XBP1s pathway in various cancers, we assembled a gene signature comprising 16 transcripts (dubbed ER16) found to be significantly upregulated in an XBP1s-dependent manner under ER stress (16,46). These genes displayed correlated expression in tumors in TCGA database (Supplementary Fig. S1A), confirming their co-regulation. Several solid-tumor types, including urothelial bladder, breast, colon, head and neck, kidney, liver, lung, stomach and uterine cancer, showed significantly elevated ER16 expression as compared to matched normal-tissue controls (Fig. 1A; Supplementary Fig. S1B). Although ER/PR+, HER2+ and TNBC breast tumors all had significant ER16 upregulation, we focused on TNBC, which urgently requires more effective biotherapies.

Fig. 1. XBP1s-driven 16-gene signature suggests activation of the IRE1α-XBP1s pathway in several solid-tumor malignancies.

(A) Expression of an XBP1s-dependent gene signature in cancer. The ER16 gene signature, which comprises 16 genes found to be regulated by XBP1s, was evaluated in samples from the Tissue Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Only cancers found to have statistically significant elevated expression relative to corresponding normal tissue with false discovery rate (FDR) of < 0.01 are shown: depicted as box-and-whisker plots, with the box indicating the median and interquartile range (IQR) and the whiskers indicating an additional 0.5 IQR interval. Cancer samples are colored red, and their corresponding normal samples dark blue. (B) Representative images from a tissue microarray of 70 TNBC patient samples stained by immunohistochemistry (IHC) for IRE1α protein using a newly generated monoclonal antibody. IHC score is based on intensity of cytoplasmic staining from none (0) to high (2+).

To assess tissue expression of IRE1α protein, we developed an immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay, based on a newly generated mouse anti-human IRE1α monoclonal antibody (GN35-18). We validated this antibody as specifically recognizing human IRE1α’s kinase domain by using purified recombinant IRE1α protein fragments and cells expressing or lacking IRE1α (Supplementary Fig. S1C–F). IHC analysis of 152 TNBC tumors via tissue microarrays revealed significant expression of the IRE1α protein in breast epithelial cells, with IHC scores ranging from 0 (40%), through 1+ (47%), to 2+ (13%) (Fig. 1B). Thus, nearly two-thirds of TNBC specimens express the IRE1α protein at levels detectable by IHC.

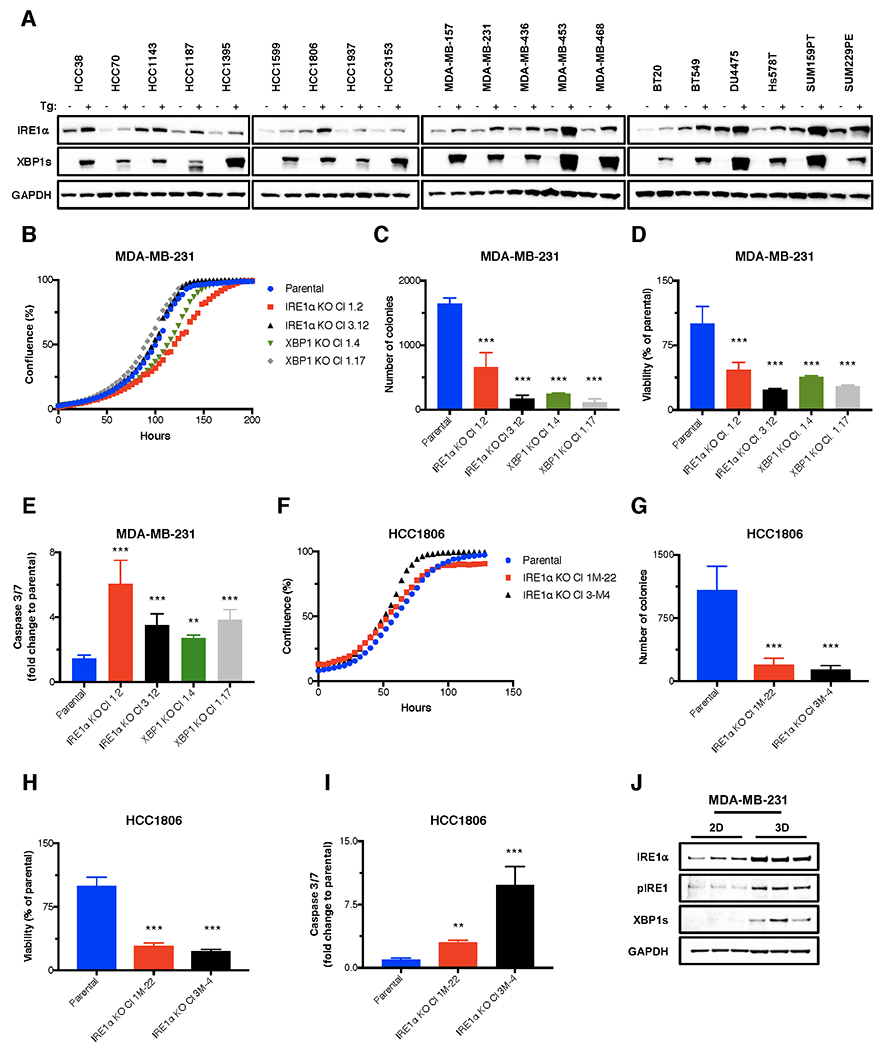

We also examined ER16 expression in a panel of 34 breast cancer cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S2A) (47). Consistent with the TCGA data, ER/PR+, HER2+ and TNBC lines showed comparable ER16 levels. Further analysis by immunoblot (IB) using anti-IRE1α and anti-XBP1s antibodies revealed detectable baseline levels of IRE1α, but not XBP1s (Fig. 2A). Nevertheless, exposure to the pharmacological ER stressor Thapsigargin (Tg) induced significant XBP1s protein amounts in all cases. Other studies detected baseline XBP1s in certain TNBC models (26,28,31): we suspect this divergence is due primarily to differences in cell culture conditions, e.g., number of passages or confluence. Regardless, although TNBC cell lines express variable levels of IRE1α, this protein appears to be uniformly poised to generate XBP1s in response to ER stress.

Fig. 2. TNBC cell lines express functional IRE1α and depend on IRE1α for in vitro growth in 3D but not 2D settings.

(A) Human TNBC cell lines were analyzed by immunoblot (IB) for protein levels of IRE1α and XBP1s. (B-E) The IRE1α or XBP1 gene was disrupted by CRISPR/Cas9 in MDA-MB-231 cells. Parental or corresponding knockout (KO) clones were seeded on standard tissue culture plates (2D) and analyzed for confluence using an Incucyte™ instrument (B); on soft agar and analyzed for colony formation after 14 days (C); on ultra-low adhesion (ULA) plates, followed by centrifugation to form single spheroids, and analyzed either for cell viability using CellTiter-Glo® 3D (D), or for caspase-3/7 activity by caspase3/7-Glo® after 7 days (E). (F-I) IRE1α was disrupted by CRISPR/Cas9 in HCC1806 cells. Parental or corresponding KO clones were seeded as above: on standard tissue culture plates (2D) and analyzed for cell growth by confluence (F); on soft agar and analyzed for colony formation (G); on ULA plates followed by centrifugation to form single spheroids and analyzed for cell viability (H), or caspase-3/7 activity (I). (J) MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded on standard tissue culture plates (2D), or ULA plates followed by centrifugation to form single spheroids (3D). After 7 days, cells were lysed and analyzed by IB for indicated proteins. **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001.

While shRNA knockdown of XBP1 attenuated TNBC growth (26,28), the effect of upstream genetic IRE1α perturbation in this context is not well defined. To examine whether TNBC cells require IRE1α itself, we disrupted the gene via CRISPR/Cas9 technology in MDA-MB-231 and HCC1806 cells; for comparison, we also disrupted XBP1 in MDA-MB-231 cells (Supplementary Fig. S2B and C). To control for inter-clonal variation, we characterized two independent KO clones for each gene.

Whereas MDA-MB-231 cells showed little dependency on either IRE1α or XBP1 for 2D growth on standard tissue culture plates, they displayed a strong reliance on either gene for 3D colony formation on soft-agar and for survival on ultra-low adhesion (ULA) plates (Fig. 2B–D). Consistent with the loss of viability, MDA-MB-231 cells harboring IRE1α or XBP1 KO displayed increased proapoptotic caspase-3/7 activity when cultured on ULA plates (Fig. 2E). HCC1806 cells similarly showed little requirement for IRE1α in 2D; strong dependency on IRE1α in 3D (Fig. 2F–H); and elevated caspase-3/7 activity during ULA culture (Fig. 2I). IB analysis of MDA-MB-231 cells revealed markedly elevated activity of IRE1α in 3D versus 2D settings, as evident by increased IRE1α protein abundance and phosphorylation, as well as elevated XBP1s protein (Fig. 2J). These results suggest that TNBC cells rely more heavily on the IRE1α-XBP1s pathway in 3D growth settings, where cell-cell adhesion is more critical for growth and survival. Supporting this idea, an RNA-seq comparison of parental versus IRE1α KO and XBP1 KO MDA-MB-231 cells revealed significant downregulation of numerous transcripts annotated with gene-ontology (GO) terms of cell-cell adhesion (Supplementary Fig. S2D).

To interrogate the importance of IRE1α for growth of TNBC tumors in vivo, we first tested the MDA-MB-231 model, which harbors MYC amplification. Albeit with some variation, MDA-MB-231 clones harboring IRE1α KO displayed markedly attenuated subcutaneous xenograft tumor growth for at least 35 days, as did clones with XBP1 KO (Fig. 3A and B; Supplementary Fig. S3A and B). Similarly, IRE1α KO clones in the HCC1806 cell line, which also carries amplified MYC, showed markedly abrogated xenograft tumor growth for at least 35 days (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Fig. S3C). Furthermore, doxycycline-inducible shRNA-based depletion of IRE1α or XBP1, but not respective control shRNA, substantially inhibited HCC1806 tumor growth (Fig. 3D and E; Supplementary Fig. S3D and E). Importantly, reconstitution of HCC1806 cells harboring shRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous IRE1α with exogenous IRE1α (RIRE1α) rescued tumor growth (Fig. 3F; Supplementary Fig. S3F and G). These data show that TNBC cells require IRE1α not only for in vivo tumor initiation but also for malignant tumor progression. TNBC cell lines with MYC amplification strongly depend on IRE1α for in vivo growth, extending and reinforcing earlier studies of XBP1s (26,28) to IRE1α—a more readily druggable target.

Fig. 3. Disruption of IRE1α or XBP1 attenuates growth of human TNBC tumor xenografts in mice.

(A) Parental MDA-MB-231 cells or corresponding IRE1α KO (A) or XBP1 KO (B) clones were injected subcutaneously into female C.B-17 SCID mice and monitored for tumor growth (A, n=15 mice/ group; B, n=5 mice/ group). (C) Parental or IRE1α KO HCC1806 cell clones were injected subcutaneously into female SCID.bg mice and monitored for tumor growth (n=15 mice/ group). (D-F) HCC1806 cells were stably transfected with Doxycycline (Dox)-inducible shRNAs against IRE1α or LacZ (D), XBP1 or NTC (E), or IRE1α + WT RIRE (F), inoculated subcutaneously into female SCID.bg mice and allowed to establish tumors of ~400 mm3 (D) or ~180 mm3 (E and F). Mice were then randomized into treatment groups of vehicle (sucrose) or Dox in drinking water (D, n=10 mice/ group; E and F, n=8 mice/ group), and tumor growth was monitored. Summary tables for each study indicating tumor growth inhibition (TGI) are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3E and G. Data represent mean tumor volume ± SEM. **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001.

Cancer cells often expand their ER to alleviate ER stress caused by intrinsic oncogene activation and by metabolically restrictive TMEs. Indeed, transmission electron microscopy-based analysis of TNBC cells cultured in vitro revealed an abnormally dilated ER, indicating stress adaptation (26). However, it is unknown whether this distended ER ultrastructure is maintained in vivo, and—perhaps more importantly—to what extent such adaptation depends on the IRE1α pathway. To address these questions, we examined size-matched MDA-MB-231 tumor xenografts by backscattered electron-scanning electron microscopy (BSE-SEM), which enables very powerful image magnification, zoomed-in from the whole tissue level to the subcellular ultrastructure level (48) (Fig. 4A). The parental tumor cells displayed a notable dilation of their ER as well as frequent bulging of their nuclear envelope, indicating marked ER adaptation within the tumor microenvironment. Strikingly, IRE1α KO tumor cells showed an essentially complete reversal of these features. Quantification of multiple BSE-SEM images confirmed a significant reduction in the number of cells with distended ER in both IRE1α KO clones as compared to parental MDA-MB-231 tumor xenografts (Fig. 4B). Thus, TNBC cells critically depend on IRE1α to adapt their ER and nuclear envelope to in vivo growth within the TME.

Fig. 4. IRE1α controls ER adaptation and vascular integrity in MDA-MB-231 tumor xenografts.

(A) BSE-SEM images of size-matched subcutaneous MDA-MB-231 parental or IRE1α KO tumor xenografts. Stars indicate nuclei, arrows indicate dilated ER cisternae and bulging of the nuclear envelope. Arrowheads indicate normal ER cisternae. Scale bars: top row (overview) = 7 μm, bottom row = 2 μm. (B) Quantification of cells with distended ER per field. Eight fields with at least 12 cells each were analyzed per xenograft sample. (C) FITC-dextran staining analysis of size-matched subcutaneous MDA-MB-231 parental or IRE1α KO tumor xenografts. Right: representative images. (D and E) Flow cytometric analysis quantifying CD31-positive endothelial cells (D) and Thy1-positive pericytes (E) in MDA-MB-231 parental and IRE1α KO tumor xenografts. **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001.

Given this cell-autonomous impact of IRE1α disruption, we turned to investigate whether IRE1α KO in malignant TNBC cells also exerts non-cell-autonomous effects on the TME. Consistent with earlier data for XBP1s shRNA (26,28), IRE1α KO markedly decreased the levels of VEGF-A mRNA and protein expression, as well as VEGF-A secretion, in MDA-MB-231 tumor xenografts (Supplementary Fig. S4A–C). RNA-seq analysis of tumor samples further indicated that multiple genes involved in the promotion of angiogenesis were downregulated upon KO of IRE1α or XBP1 (Supplementary Fig. S4D). We tested and confirmed this observation by qRT-PCR analysis of angiogenin mRNA (Supplementary Fig. S4E). Moreover, IB analysis of MDA-MB-231 xenografts verified that IRE1α KO diminished the abundance of several pro-angiogenic proteins, namely, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1), angiopoietin-1, and angiogenin (Supplementary Fig. S4F).

Normalization of the tumor vasculature is critical for the effectiveness of anti-angiogenic therapy (49–51). However, whether the IRE1α pathway affects this endpoint is unknown. To address this question, we performed vascular perfusion of tumors with FITC-dextran, followed by microscopic analysis of tumor tissue by IHC (Fig. 4C). Viable parts of IRE1α KO MDA-MB-231 tumors contained significantly less FITC-dextran-positive areas than did parental controls, suggesting a marked decrease in leakage of this large molecule from within tumor vessels into the extravascular tissue space. Further analysis of tumors by FACS revealed that the levels of CD31-positive endothelial cells were unaffected (Fig. 4D). In keeping, IHC analysis of pan-endothelial cell antigen (MECA)-32 staining showed only a small, albeit statistically significant, decrease in IRE1α KO versus parental tumors (Supplementary Fig. S4G). By contrast, numbers of Thy1-positive pericytes were significantly increased upon IRE1α KO (Fig. 4E). In agreement with these findings, flow cytometric analysis of HCC1806 tumor xenografts showed an insignificant decrease in CD31-positive endothelial cells, but a significant elevation in Thy1-positive pericytes upon IRE1α KO (Supplementary Fig. S4H and I). Together, these results indicate that IRE1α perturbation in the malignant TNBC cells increases the level of pericytes relative to endothelial cells within the TME, thus providing a likely mechanistic explanation for the observed tumor-vascular normalization upon IRE1α disruption.

In light of our findings with genetic IRE1α disruption, we turned to investigate the effect of pharmacological IRE1α inhibition, which would block the pathway both in malignant and non-malignant cells within the TME. In previous studies, inhibition of IRE1α at the RNase level attenuated growth of TNBC tumor xenografts, particularly when performed in conjunction with taxane chemotherapy (28,31). However, the impact of likely more target-selective pharmacological perturbation of IRE1α at the kinase level on TNBC tumor growth is unknown. To determine this, we used compound 18—previously validated as a selective and effective allosteric inhibitor of IRE1α that acts via binding to the ATP pocket within the kinase domain (41,42). Given that XBP1s cooperates with HIF1α to upregulate VEGF-A (26), and the vascular changes we observed upon IRE1α KO in TNBC cells, we compared the anti-tumor activity of compound 18 with that of a previously established anti-VEGF-A neutralizing antibody, which blocks both murine and human VEGF-A (43,52). In the MDA-MB-231 model, compound 18 treatment caused significant tumor growth inhibition (TGI 93%, range 81-102%). Anti-VEGF-A monotherapy showed weaker efficacy (TGI 62%, range 43-76%). Remarkably, treatment with both agents together enabled complete suppression of tumor growth in 6/14 mice and tumor regression in 8/14 mice (TGI 121%, range 112-131%, p<0.05 as compared to compound 18 monotherapy) (Fig. 5A; Supplementary Fig. S5A–C). Similarly, in the HCC1806 model compound 18 treatment also attenuated tumor growth more substantially (TGI 78%, range 69-85%) than anti-VEGF-A monotherapy (TGI 54%, range 38-64%), while combination of both treatments led to complete tumor growth suppression in 13/20 mice and tumor regression in 7/20 mice (TGI 109%, range 105-113%, p<0.001 as compared to compound 18 monotherapy) (Fig. 5B; Supplementary Fig. S5D–F).

Fig. 5. IRE1α kinase inhibition impairs growth of subcutaneous and orthotopic human TNBC tumor xenografts in mice and cooperates with anti-VEGF-A antibody therapy to cause tumor regression.

(A-C) MDA-MB-231 (A) or HCC1806 cells (B) were inoculated subcutaneously into female C.B-17 SCID (A) or SCID.bg mice (B), or HCI-004 tumor fragments were surgically transplanted into the mammary fat pad of female NOD SCID mice (C) and allowed to establish tumors of ~150 mm3. Mice were then randomized into the following groups (n=15/ group in A and C, n=20/ group in B): (i) vehicle; (ii) anti-VEGF-A (2 mg/kg) intraperitoneally (IP) twice per week (BIW); (iii) compound 18 (30 mg/kg) IP once per day (QD); or (iv) combination of compound 18 and anti-VEGF-A. Tumor growth was monitored for the indicated time. Individual tumor data are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5A (for A), Supplementary Fig. S5D (for B) and Supplementary Fig. S5I (for C). (D) Expression of Cox-2 (PTGS2), CXCL8, and CXCR4 in HCC1806 parental or IRE1α KO subcutaneous tumor xenografts treated with or without anti-VEGF-A for 7 days was analyzed by RNA-seq. (E and F) Flow cytometric analysis quantifying Pdpn-positive and Pdgfrα-positive CAFs in subcutaneous MDA-MB-231 (E) or HCC1806 (F) tumor xenografts treated with Compound 18, anti-VEGF-A, or the combination of both as outlined above. (G) FAP staining analysis of subcutaneous MDA-MB-231 parental or IRE1α KO tumor xenografts. Right: representative images. In vivo data depict mean tumor volume ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001.

Next, we turned to PDx models, which set a higher bar for preclinical validation of potential therapeutic targets. We first determined IRE1α expression by IHC and IB in three PDx TNBC tissue samples (Supplementary Fig. S5G). While all three tumors displayed detectable IRE1α protein, HCI-004, which harbors amplified MYC, had higher levels, comparable to other TNBC samples scored earlier as 2+ (Fig. 1B). IB analysis confirmed that HCI-004 expressed relatively higher levels of both IRE1α and XBP1s (Supplementary Fig. S5H), suggesting stronger IRE1α pathway engagement. We therefore tested this model in vivo, by orthotopic transplantation of tumor tissue into the mammary fat pad of female NOD-SCID mice (Fig. 5C; Supplementary Fig. S5I–K). Monotherapy with compound 18 substantially inhibited tumor growth (TGI 89%, range 78-96%), while anti-VEGF-A administration showed less efficacy (TGI 51%, range 38-62%). Again, combination treatment was markedly more effective, leading to tumor regression in 14/14 animals (TGI 117%, range 110-126%, p<0.05 as compared to compound 18 monotherapy). Thus, IRE1α kinase inhibition strongly attenuates TNBC tumor growth in cell-line-based subcutaneous as well as patient-derived orthotopic models. While IRE1α kinase inhibition provided substantial benefit, the two modalities cooperated to achieve significantly better tumor growth control or even a reversal of tumor progression.

Consistent with our earlier observations upon IRE1α KO (Fig. 4E), treatment of MDA-MB-231 tumor bearing mice with Compound 18 diminished serum levels of human VEGF-A (Supplementary Fig. S5L) and decreased vascular leakage as judged by FITC-dextran staining (Supplementary Fig. S5M). We next explored whether IRE1α disruption also impacts non-vascular gene targets and cells within the TME. RNA-seq comparison of parental and IRE1α or XBP1 KO MDA-MB-231 xenografts revealed transcriptional downregulation of several genes known to be involved in the recruitment of CAFs and MDSCs, namely, Cox-2 (PTGS2), CXCL8, and CXCR4 (Supplementary Fig. S4D) (53–55). Deconvolution analysis of bulk RNA-seq data comparing MDA-MB-231 parental and IRE1α KO xenografts, by referring to reported single-cell RNA-seq gene signatures for CAFs (56), suggested that podoplanin (Pdpn) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor A (Pdgfrα) double-positive CAFs (dubbed CAF2), which are considered to drive the desmoplastic reaction associated with tumor development, are reduced in the TME (Supplementary Fig. S5N). To assess if this modulation of the TME could contribute to the observed synergy between IRE1α and VEGF-A, we examined the expression of Cox-2 (PTGS2), CXCL8, and CXCR4 in the HCC1806 model by comparing RNA-seq data of parental and IRE1α KO xenografts treated with or without anti-VEGF-A. Consistent with the results in the MDA-MB-231 model, perturbation of IRE1α—but importantly, not anti-VEGF-A treatment—strongly diminished the expression of these three genes (Fig. 5D). In light of these results, we investigated tumor infiltration of CAFs and MDSCs in MDA-MB-231 and HCC1806 tumor xenografts. Flow cytometric analysis of Pdpn and Pdgfrα double-positive cells, as well as IHC analysis of fibroblast activation protein (FAP) staining suggested that compound 18 treatment alone or in combination with anti-VEGF-A—but again, not anti-VEGF-A treatment alone—significantly decreased tumor levels of CAF2 cells (Fig. 5E–G). Furthermore, flow cytometric analysis also indicated a significantly diminished number of tumor-infiltrating MDSCs following perturbation of IRE1α alone or in combination with anti-VEGF-A—but not upon anti-VEGF-A monotherapy (Supplementary Fig. S5O and P). These results suggest that IRE1α inhibition disrupts tumor growth by remodeling the TME.

Discussion

Our work conceptually advances the current mechanistic and therapeutic understanding of the IRE1α pathway in TNBC. In particular, we demonstrate that (1) TNBC cells critically rely on IRE1α to adjust their ER for malignant in vivo growth; (2) Disruption of IRE1α impairs vascular density and decreases vessel leakage within TNBC tumors by increasing pericyte to endothelial cell ratios; (3) IRE1α inhibition decreases Cox-2 (PTGS2), CXCL8, and CXCR4 mRNA, reducing the number of tumor-infiltrating CAF2 cells and MDSCs—cell types conducive to tumor vascularization and malignant progression; (4) Inhibition of IRE1α at the kinase level significantly attenuates TNBC tumor growth as monotherapy and cooperates with anti-VEGF-A antibody to cause frequent tumor regression.

Intriguingly, TNBC cells growing in vitro in 3D settings as compared to 2D culture exhibited markedly increased activation of the IRE1α pathway and a much stronger dependency on IRE1α. This data is reminiscent of our recent observations with multiple myeloma cells (42). We hypothesize that both types of cancer cells require IRE1α-supported cell-cell adhesion mechanisms for survival in 3D growth settings. Consistent with this notion, RNA-seq analysis showed that IRE1α or XBP1 KO in TNBC cells downregulates numerous transcripts known to enable cell-cell adhesion, which implicates the IRE1α pathway as a key facilitator of this important cellular function.

In our in vivo experiments, KO or knockdown of either IRE1α or XBP1 substantially inhibited growth of TNBC xenografts, demonstrating a critical role for IRE1α itself in driving TNBC progression (26,28). Mechanistically, we observed a strong cell-autonomous requirement of IRE1α for ultrastructural ER and nuclear envelope adaptation in TNBC cells. These IRE1α-dependent changes appeared to have major consequences not only directly, for the malignant cells, but also indirectly, for other cell types within the TME. Non-cell-autonomous changes caused by IRE1α pathway disruption may be linked to altered folding and secretion of ER-client proteins destined for the cell surface and extracellular space. Our finding that IRE1α KO decreases VEGF-A transcript and protein levels as well as VEGF-A secretion in TNBC tumor xenografts extends earlier XBP1s data (26) to IRE1α upstream. Furthermore, we obtained evidence suggesting that IRE1α disruption decreases vascular leakage by promoting vascular pericyte coverage—likely a beneficial aspect of anti-angiogenic therapy that may improve drug delivery to tumors and decrease tumor invasion and metastasis (49–51). The IRE1α kinase inhibitor used in this study as a tool molecule afforded marked suppression of tumor XBP1s levels and displayed significant single-agent efficacy, reaching approximately 90% TGI. This demonstrates for the first time that kinase-based IRE1α inhibition is therapeutically efficacious in models of a solid-tumor malignancy.

In breast cancer clinical trials, anti-VEGF-A therapy was not sufficiently beneficial to garner FDA approval (34). In the present preclinical study, anti-VEGF-A antibody treatment afforded approximately 50-60% TGI in three distinct TNBC models. IRE1α perturbation showed superior efficacy by exerting stronger changes in the TME, significantly decreasing the number of tumor-infiltrating CAFs and MDSCs. Our RNA-seq analyses of xenograft samples from two distinct TNBC models detected several IRE1α- and XBP1-dependent genes, i.e., Cox-2, CXCL8 and CXCR4, which could individually or in concert contribute to the reduction of CAFs and MDSCs upon IRE1α perturbation. CAFs promote angiogenesis and tumor progression in breast cancer via SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling (57). Tumor epithelial expression of Cox-2 correlates with higher CAF numbers in the TME of TNBC xenografts and promotes tumor progression in breast cancer models (53,58,59). Furthermore, the Cox2–PGE2 pathway drives angiogenesis and tumor growth independent of VEGF-A (59). Importantly, disruption of the Cox2–PGE2 pathway also attenuates MDSC recruitment via the CXCL8-CXCR1/2 and CXCL12-CXCR4 signaling pathways (54,55). Together, our results suggest that IRE1α inhibition, likely in conjunction with consequent Cox-2 downregulation, disrupts TNBC tumor growth by remodeling the cellular composition of the TME in modes that are both overlapping with (i.e., effects on the tumor vasculature) and complementary to (i.e., diminished tumor recruitment of CAFs and MDSCs) VEGF-A inhibition in modes that are both overlapping (i.e. tumor vasculature) as well as complementary (i.e. CAF2 cells and MDSCs) to VEGF-A inhibition, enabling synergy between these two therapeutic strategies. These findings support investigating this type of combination approach in the clinic, provided that appropriate safety can be established in suitable pre-clinical models. Of note in this context, IRE1α kinase inhibition was not associated with overt toxicity in mice, nor did it disrupt viability of primary human hepatocytes and glucose-induced insulin secretion by human pancreatic micro-islet cultures (42).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a critical role for IRE1α in adapting the ER of malignant TNBC cells and remodeling their TME to facilitate malignant tumor progression. This work provides a compelling rationale for small-molecule targeting of IRE1α in this yet unconquered lethal disease. Furthermore, IRE1α inhibition has the potential to augment the efficacy of anti-angiogenic therapy—for TNBC, and perhaps beyond. Evidently, the IRE1α pathway is activated in several additional solid-tumor malignancies, which supports exploring whether similar mechanistic-therapeutic concepts apply more broadly to other cancers.

Supplementary Material

Statement of significance.

Pharmacologic IRE1α kinase inhibition reverses ultrastructural distension of the ER, normalizes the tumor vasculature, and remodels the cellular tumor microenvironment, attenuating TNBC growth in mice.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a Howard Hughes Collaborative Innovation Award to P.W., who is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

We thank Marie Gabrielle-Braun for compound synthesis, Scott Stawicki for antibody generation, Jing Qing for shRNA design, Ben Haley for gRNA design, and Stephen Gould, Bob Yauch, Frank Peale, Daniel Sutherlin, and Ira Mellman for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

J.M.H., A.L.T., M.R., O.G., T.D.W., S.A.M., A.S., D.A.L., D.K., E.S., M.M., K.T., L.C., K.M., M.D., M.S., Z.M., J.R., H.K., and A.A. were employees of Genentech, Inc. during performance of this work. P.W. declares no potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Brown M, Tsodikov A, Bauer KR, Parise CA, Caggiano V. The role of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 in the survival of women with estrogen and progesterone receptor-negative, invasive breast cancer: the California Cancer Registry, 1999-2004. Cancer 2008;112:737–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1938–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 2011;334:1081–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hetz C The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012;13:89–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Bettigole SE, Glimcher LH. Tumorigenic and Immunosuppressive Effects of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Cancer. Cell 2017;168:692–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabas I, Ron D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Cell Biol 2011;13:184–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox JS, Shamu CE, Walter P. Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell 1993;73:1197–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KP, Dey M, Neculai D, Cao C, Dever TE, Sicheri F. Structure of the dual enzyme Ire1 reveals the basis for catalysis and regulation in nonconventional RNA splicing. Cell 2008;132:89–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tirasophon W, Welihinda AA, Kaufman RJ. A stress response pathway from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus requires a novel bifunctional protein kinase/endoribonuclease (Ire1p) in mammalian cells. Genes Dev 1998;12:1812–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korennykh AV, Egea PF, Korostelev AA, Finer-Moore J, Zhang C, Shokat KM, et al. The unfolded protein response signals through high-order assembly of Ire1. Nature 2009;457:687–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han D, Lerner AG, Vande Walle L, Upton JP, Xu W, Hagen A, et al. IRE1alpha kinase activation modes control alternate endoribonuclease outputs to determine divergent cell fates. Cell 2009;138:562–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu Y, Liang FX, Wang X. A synthetic biology approach identifies the mammalian UPR RNA ligase RtcB. Mol Cell 2014;55:758–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang M, Kaufman RJ. Protein misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum as a conduit to human disease. Nature 2016;529:326–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Travers KJ, Patil CK, Wodicka L, Lockhart DJ, Weissman JS, Walter P. Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell 2000;101:249–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaffer AL, Shapiro-Shelef M, Iwakoshi NN, Lee AH, Qian SB, Zhao H, et al. XBP1, downstream of Blimp-1, expands the secretory apparatus and other organelles, and increases protein synthesis in plasma cell differentiation. Immunity 2004;21:81–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acosta-Alvear D, Zhou Y, Blais A, Tsikitis M, Lents NH, Arias C, et al. XBP1 controls diverse cell type- and condition-specific transcriptional regulatory networks. Mol Cell 2007;27:53–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hollien J, Weissman JS. Decay of endoplasmic reticulum-localized mRNAs during the unfolded protein response. Science 2006;313:104–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollien J, Lin JH, Li H, Stevens N, Walter P, Weissman JS. Regulated Ire1-dependent decay of messenger RNAs in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol 2009;186:323–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu M, Lawrence DA, Marsters S, Acosta-Alvear D, Kimmig P, Mendez AS, et al. Opposing unfolded-protein-response signals converge on death receptor 5 to control apoptosis. Science 2014;345:98–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang TK, Lawrence DA, Lu M, Tan J, Harnoss JM, Marsters SA, et al. Coordination between Two Branches of the Unfolded Protein Response Determines Apoptotic Cell Fate. Mol Cell 2018;71:629–36 e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bae D, Moore KA, Mella JM, Hayashi SY, Hollien J. Degradation of Blos1 mRNA by IRE1 repositions lysosomes and protects cells from stress. J Cell Biol 2019;218:1118–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011;144:646–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang M, Kaufman RJ. The impact of the endoplasmic reticulum protein-folding environment on cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer 2014;14:581–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moenner M, Pluquet O, Bouchecareilh M, Chevet E. Integrated endoplasmic reticulum stress responses in cancer. Cancer Res 2007;67:10631–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clarke R, Cook KL. Unfolding the Role of Stress Response Signaling in Endocrine Resistant Breast Cancers. Front Oncol 2015;5:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X, Iliopoulos D, Zhang Q, Tang Q, Greenblatt MB, Hatziapostolou M, et al. XBP1 promotes triple-negative breast cancer by controlling the HIF1alpha pathway. Nature 2014;508:103–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selfors LM, Stover DG, Harris IS, Brugge JS, Coloff JL. Identification of cancer genes that are independent of dominant proliferation and lineage programs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:E11276–E84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao N, Cao J, Xu L, Tang Q, Dobrolecki LE, Lv X, et al. Pharmacological targeting of MYC-regulated IRE1/XBP1 pathway suppresses MYC-driven breast cancer. J Clin Invest 2018;128:1283–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheng X, Nenseth HZ, Qu S, Kuzu OF, Frahnow T, Simon L, et al. IRE1alpha-XBP1s pathway promotes prostate cancer by activating c-MYC signaling. Nat Commun 2019;10:323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie H, Tang CH, Song JH, Mancuso A, Del Valle JR, Cao J, et al. IRE1alpha RNase-dependent lipid homeostasis promotes survival in Myc-transformed cancers. J Clin Invest 2018;128:1300–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Logue SE, McGrath EP, Cleary P, Greene S, Mnich K, Almanza A, et al. Inhibition of IRE1 RNase activity modulates the tumor cell secretome and enhances response to chemotherapy. Nat Commun 2018;9:3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umansky V, Blattner C, Gebhardt C, Utikal J. The Role of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSC) in Cancer Progression. Vaccines (Basel) 2016;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo H, Tu G, Liu Z, Liu M. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: a multifaceted driver of breast cancer progression. Cancer Lett 2015;361:155–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ribatti D, Nico B, Ruggieri S, Tamma R, Simone G, Mangia A. Angiogenesis and Antiangiogenesis in Triple-Negative Breast cancer. Transl Oncol 2016;9:453–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 2011;473:298–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohammed RA, Ellis IO, Mahmmod AM, Hawkes EC, Green AR, Rakha EA, et al. Lymphatic and blood vessels in basal and triple-negative breast cancers: characteristics and prognostic significance. Mod Pathol 2011;24:774–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romero-Ramirez L, Cao H, Nelson D, Hammond E, Lee AH, Yoshida H, et al. XBP1 is essential for survival under hypoxic conditions and is required for tumor growth. Cancer Res 2004;64:5943–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghosh R, Lipson KL, Sargent KE, Mercurio AM, Hunt JS, Ron D, et al. Transcriptional regulation of VEGF-A by the unfolded protein response pathway. PLoS One 2010;5:e9575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruan Q, Xi L, Boye SL, Han S, Chen ZJ, Hauswirth WW, et al. Development of an anti-angiogenic therapeutic model combining scAAV2-delivered siRNAs and noninvasive photoacoustic imaging of tumor vasculature development. Cancer Lett 2013;332:120–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou J, Wang XH, Zhao YX, Chen C, Xu XY, Sun Q, et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Correlate with Tumor-Associated Macrophages Infiltration and Lymphatic Metastasis in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Patients. J Cancer 2018;9:4635–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harrington PE, Biswas K, Malwitz D, Tasker AS, Mohr C, Andrews KL, et al. Unfolded Protein Response in Cancer: IRE1alpha Inhibition by Selective Kinase Ligands Does Not Impair Tumor Cell Viability. ACS Med Chem Lett 2015;6:68–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harnoss JM, Le Thomas A, Shemorry A, Marsters SA, Lawrence DA, Lu M, et al. Disruption of IRE1alpha through its kinase domain attenuates multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:16420–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liang WC, Wu X, Peale FV, Lee CV, Meng YG, Gutierrez J, et al. Cross-species vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-blocking antibodies completely inhibit the growth of human tumor xenografts and measure the contribution of stromal VEGF. J Biol Chem 2006;281:951–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeRose YS, Wang G, Lin YC, Bernard PS, Buys SS, Ebbert MT, et al. Tumor grafts derived from women with breast cancer authentically reflect tumor pathology, growth, metastasis and disease outcomes. Nat Med 2011;17:1514–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pinheiro J, Bornkamp B, Glimm E, Bretz F. Model-based dose finding under model uncertainty using general parametric models. Stat Med 2014;33:1646–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH. XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol 2003;23:7448–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chavez KJ, Garimella SV, Lipkowitz S. Triple negative breast cancer cell lines: one tool in the search for better treatment of triple negative breast cancer. Breast Dis 2010;32:35–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reichelt M, Sagolla M, Katakam AK, Webster JD. Unobstructed Multiscale Imaging of Tissue Sections for Ultrastructural Pathology Analysis by Backscattered Electron Scanning Microscopy. J Histochem Cytochem 2019:22155419868992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goel S, Duda DG, Xu L, Munn LL, Boucher Y, Fukumura D, et al. Normalization of the vasculature for treatment of cancer and other diseases. Physiol Rev 2011;91:1071–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Principles and mechanisms of vessel normalization for cancer and other angiogenic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2011;10:417–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwartz MA, Vestweber D, Simons M. A unifying concept in vascular health and disease. Science 2018;360:270–1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Gerber HP, Novotny W. Discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2004;3:391–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krishnamachary B, Stasinopoulos I, Kakkad S, Penet MF, Jacob D, Wildes F, et al. Breast cancer cell cyclooxygenase-2 expression alters extracellular matrix structure and function and numbers of cancer associated fibroblasts. Oncotarget 2017;8:17981–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Obermajer N, Muthuswamy R, Lesnock J, Edwards RP, Kalinski P. Positive feedback between PGE2 and COX2 redirects the differentiation of human dendritic cells toward stable myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Blood 2011;118:5498–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kalinski P Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin E2. J Immunol 2012;188:21–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davidson S, Efremova M, Riedel A, Mahata B, Pramanik J, Huuhtanen J, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals a dynamic stromal niche within the evolving tumour microenvironment. bioRxiv 2018:467225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Delaunay T, Naeem R, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell 2005;121:335–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu M, Peluffo G, Chen H, Gelman R, Schnitt S, Polyak K. Role of COX-2 in epithelial-stromal cell interactions and progression of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:3372–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ben-Batalla I, Cubas-Cordova M, Udonta F, Wroblewski M, Waizenegger JS, Janning M, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 blockade can improve efficacy of VEGF-targeting drugs. Oncotarget 2015;6:6341–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.