Abstract

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is one of the fastest-growing concerns worldwide. In addition to bacterial endotoxins in the portal circulation, recent lines of evidence have suggested that sterile inflammation caused by a wide range of stimuli induces alcoholic liver injury, in which damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) play critical roles in inducing de novo lipogenesis and inflammation through the activation of cellular pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors in non-parenchymal cells. Interestingly, alcohol-mediated metabolic, neurological, and immune stresses stimulate the generation of DAMPs that are released not only in the liver, but also in other organs, such as adipose tissue, intestine, and bone marrow. Thus, diverse DAMPs, including retinoic acids, proteins, lipids, microRNAs, mitochondrial DNA, and mitochondrial double-stranded RNA, contribute to a broad spectrum of ALD through the production of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and ligands in non-parenchymal cells, such as Kupffer cells, hepatic stellate cells, and various immune cells. Therefore, this review summarizes recent studies on the identification and understanding of DAMPs, their receptors, and cross-talk between the liver and other organs, and highlights successful therapeutic targets and potential strategies in drug development that can be used to combat ALD.

Subject terms: Cell biology, Alcoholic liver disease

Alcoholic liver disease: cross-talk with other organs

Therapies preventing the distribution of damage-associated molecules from other organs to the liver could help tackle alcoholic liver disease (ALD). Over time, metabolites from excessive alcohol consumption induce oxidative stress, damaging liver cells. Injured hepatocytes release molecules known as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), including proteins, RNA, and metabolites, which disperse within the liver and other organs and trigger chronic inflammation. Won-Il Jeong and Young-Ri Shim at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology in Daejeon reviewed understanding of DAMPs to identify possible therapeutic targets for ALD. DAMPs are carried between cells by extracellular vesicles, particles released during cellular communication. Alcohol-induced DAMPs in other organs, such as the gut, can deliver to the liver, and it influences ALD progression. The more-detailed cross-talk between the liver and other organs in ALD requires further investigation.

Introduction

Chronic alcohol consumption is the third highest health risk in the world. The World Health Organization has reported that the abuse of alcohol kills up to three million people per year globally; it accounts for ~5% of the global disease burden in 20181,2. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) progresses from a mild form of alcoholic fatty liver to severe forms, such as alcoholic steatohepatitis, alcoholic hepatitis, alcoholic fibrosis/cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)2,3.

In general, three inflammatory pathways primarily trigger ALD, wherein a change in intestinal microbiome composition increases the amount of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that further mediate activation of Kupffer cells through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Moreover, damage to hepatocytes by alcohol metabolites generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), lipid-originated metabolites (retinoic acid and endocannabinoids), and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) to stimulate inflammatory signals through Toll-like receptors (TLRs), nuclear/neuronal receptors, and the inflammasome2,4. Furthermore, inter-organ cross-talk contributes to ALD by delivering DAMPs or migrating inflammatory cells to the liver. Through these processes, hepatocytes and non-parenchymal cells produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines to recruit additional immune cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages. In addition, diverse types of hepatic lymphocytes that are activated by PAMPs, DAMPs, and cytokines promote liver injury by producing interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-22, IL-17, etc5. Recent emerging data on sterile inflammation may bring to light potential therapeutic targets for ALD. Thus, this review describes the current state of understanding concerning the pathophysiological mechanisms of DAMP- and PAMP-mediated inflammation and organ cross-talk in ALD. In addition, we briefly summarize lists of DAMPs and PAMPs in ALD (Table 1).

Table 1.

DAMPs and PAMPs in ALD.

| Origin | Ligands | Receptors | Functions | Cells | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAMPs | Glutamate | mGluR5 | 2-AG production | HSC | 24 |

| HMGB1 | TLR4, RAGE | Post-translational modification | Macrophage/Kupffer cell | 7 | |

| ATP | P2X7 | Inflammasome activation | Macrophage/Kupffer cell | 9 | |

| MicroRNA (miRNA) | ‒ | M1 polarization | Macrophage/Kupffer cell | 14 | |

| Mitochondrial dsRNA | TLR3 | IL-1β | Macrophage | 16 | |

| Mitochondrial DNA | TLR9, NLRP3 | IL-1β, IL-17A | Kupffer cell/neutrophil/tumor cell | 8,20 | |

| Nuclear (apoptotic) DNA | TLR9 | TGF-β, collagen | HSC | 19 | |

| EV ligands (miRNA, CD40L, HSP90) | CD40 | TNF-α, IL-1β, M1 polarization | Macrophage/Kupffer cell | 13,21,22 | |

| Metabolites (RAs) | RARs, RXRs | RAE, IFN-γ | HSCs | 27,29–31 | |

| Lipids (FFAs, TG) | CD36 | Lipotoxicity | Hepatocyte | 42,57 | |

| PAMPs | LPS | TLR4 | TNF-α, IL-1β | Kupffer cell | 35,36 |

| LTA | TLR2 | TNF-α | Kupffer cell | 36 | |

| CpG DNA | TLR9 | TNF-α | Kupffer cell | 21 | |

| Flagellin | TLR5 | TNF-α, IL-22 | Kupffer cell, Immune cell at the ileum | 36,37 | |

| β-glucan | CLEC7A | IL-1β | Kupffer cell | 87 |

mGluR5 metabotropic glutamate receptor 5, 2-AG 2-Arachidonoylglycerol, HSC hepatic stellate cell, HMGB1 high mobility group box-1, TLR toll-like receptor, ATP adenosine triphosphate, IL interleukin, NLRP3 NLR family pyrin domain containing 3, TGF transforming growth factor, EV extracellular vesicle, CD40L CD40 ligand, HSP90 heat shock protein 90, TNF tumor necrosis factor, RA retinoic acid, RAR retinoic acid receptors, RXRs retinoid X receptor, RAE retinoic acid early inducible, IFN interferon, FFA free fatty acid, TG triglyceride, LPS lipopolysaccharide, LTA lipoteichoic acid, CLEC7A C-type lectin domain containing 7A.

Damps in ALD

Alcohol metabolism and DAMPs

In the early stage of alcohol consumption, alcohol is metabolized to acetaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenase, which is further converted to acetate by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase6; however, chronic exposure results in alcohol metabolism occurring mainly through cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1)7. In the late stage, alcohol metabolism-induced oxidative stresses cause damage to hepatocytes, in which DAMPs, including high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1), mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), mitochondrial double-stranded RNA (mtdsRNA), microRNAs (miRNAs), ATP, and several metabolites are generated and released from the injured hepatocytes, leading to sterile inflammation in ALD8–10. In addition to recognizing TLRs, DAMPs amplify liver injury by stimulation of the inflammasome, which activates caspase-1 and secretes the pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-18, which play important roles in ALD5,11,12.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), miRNA, mtdsRNA, and mtDNA in ALD

EVs, such as exosomes, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies, play important roles in cell-to-cell communication by delivering hepatic DAMPs to target cells13. Recent studies in mice and patients with alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) have demonstrated that many miRNAs are not only generated within the cells but can also be transferred into other target cells via EVs14. For instance, miR-27a from alcohol-exposed monocytes can program naive monocytes to polarize into M2 macrophages15. In addition, mtdsRNA can be generated by the inhibition of restricting enzymes, such as mitochondrial RNA helicase SUV3 and polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase)16. We recently found that accumulation of mtdsRNA is induced in ethanol-exposed hepatocytes through downregulated expression of PNPase, and exosomal delivery of mtdsRNA to Kupffer cells leads to an augmentation of IL-17 production in hepatic γδ T cells and the severity of acute ALD in a TLR3-dependent manner17. In RNA-sequencing analysis, most mitochondrial mRNAs were enhanced in ethanol-exposed exosomes, whereas mitochondrial DNAs were mainly enriched in microvesicles after treating hepatocytes with ethanol in vitro17. Another study strongly suggested that hepatocyte mtdsRNA could act as self-ligands to TLR3, which could aggravate not only ALD but also other liver diseases17,18. In contrast, poly I:C-mediated multiple activation of TLR3 in Kupffer cells and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) attenuates hepatic steatosis and inflammation via IL-10 production19. Thus, the roles of TLR3 should be investigated carefully in further studies. Similarly, previous studies have reported that nuclear DNA and mtDNA of damaged hepatocytes contribute to ALD. For example, EVs deliver hepatocyte-derived apoptotic DNA and mtDNA to HSCs, neutrophils or tumor cells, consequently accelerating liver fibrosis, alcoholic hepatitis, and HCC, respectively, through TLR99,20,21. In addition to nucleic acids, CD40 ligands and heat shock protein 90 present in EVs stimulate the production of TNF-α and IL-1β in macrophages in mice and patients with alcoholic hepatitis, in vitro and in vivo22,23. Therefore, EVs could be therapeutic targets for ALD.

Glutamate and endocannabinoids in ALD

During the last decade, studies have demonstrated that the bidirectional cross-talk between hepatocytes and HSCs contributes to alcoholic steatosis, in which a line of neurological responses between hepatocytes and HSCs suggests the presence of a metabolic synapse24,25. Alcoholic steatosis is mediated by activation of the endocannabinoid-induced CB1 receptor (CB1R) in hepatocytes, in which the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) in HSCs interacts with hepatocyte-derived glutamate and generates the endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), after alcohol exposure25. Chronic alcohol exposure induces CYP2E1-mediated oxidative stress, which suppresses the methionine cycle and transsulfuration system, and decreases cysteine concentrations hepatocytes, thereby lowering the levels of the antioxidant molecule glutathione (GSH)26. Moreover, to compensate for the GSH shortage, hepatocytes take up extracellular cystine by exchanging it with glutamate through the xCT transporter, whereas HSCs generate 2-AG through mGluR5-mediated diacylglycerol lipase-β activation25. The produced 2-AG, in turn, stimulates hepatic CB1R to induce de novo lipogenesis by upregulating sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP1c) and downregulating AMP-activated protein kinase in hepatocytes, leading to fat accumulation. Furthermore, we found that chronic alcohol consumption increases glutamate generation from glutamic-γ-semialdehyde through upregulation of ALDH4A1 expression in perivenous hepatocytes25, suggesting that the glutamate released from damaged hepatocytes might be a type of DAMP. Therefore, a functional metabolic synapse between hepatocytes and HSCs may be a critical therapeutic target for ALD.

Retinoic acids in ALD

The liver is a representative organ for storage and metabolism of retinol (vitamin A)27. In particular, quiescent HSCs store ~80% of total liver retinols as retinyl palmitate in fat droplets, whereas activated HSCs lose their retinols by releasing or metabolizing retinols into retinoids, including retinoic acids (RAs), in response to liver injury2,27. In HSCs, a class III ADH3 enzyme plays a critical role in retinol metabolism, and the metabolized RAs bind to retinoic acid receptors (RAR-α/β/γ) and retinoic X receptors (RXR-α/β/γ) and regulate gene expression2,28. Although the exact underlying mechanism by which HSCs lose or metabolize retinols in ALD is still unclear, HSCs do not induce liver fibrosis after chronic ethanol consumption in mice2. It is probable that activated HSCs express retinoic acid early inducible gene 1 (RAE1), which is a specific ligand for natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D) in natural killer (NK) cells, and then hepatic NK cells specifically kill the activated HSCs by producing IFN-γ in response to the RAE1-NKG2D interaction at an early stage of ALD2,29. In contrast, in an advanced stage of liver disease, activated HSCs show resistance to NK cell cytotoxicity via 9-cis forms of retinoid-mediated production of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 and the expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling protein 1 (SOCS1)29–31. In addition, a study reported that retinol metabolism in HSCs inhibits the recruitment of regulatory T cells (Tregs), whereas blocking retinol metabolism mitigates Concanavalin A-induced hepatitis through increased migration of Tregs in mice32. As mentioned above, liver diseases including ALD stimulate retinol metabolism of HSCs, and retinoids trigger transcription of diverse genes through their nuclear receptors, inducing beneficial or detrimental functions related to liver diseases. However, to implicate retinols as DAMPs in ALD, the exact molecular signaling pathways of retinol metabolism in HSCs and functions in the cells should be clearly investigated, and then these molecules might be therapeutic targets for ALD in the future.

PAMPS in ALD

The liver–gut axis is a critical pathway for ALD because it is a central player in the response to gut bacteria-originated PAMPs, as well as nutrients received through the portal vein. In this regard, ALD does not represent a true sterile inflammatory liver disease. Thus, we briefly address the role of PAMPs in ALD here. Alcohol consumption affects multiple defense barriers, including chemical, physical, and immune factors in the gut4. Impairment of this barrier owing to acute, binge, or chronic alcohol intake increases blood levels of bacterial components and their products (e.g., PAMPs) in animal models and humans33,34. Among bacterial PAMPs, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and bacterial DNA interact with TLR4 and TLR9, respectively, and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-1β through NF-κB in innate immune cells, including Kupffer cells. Similarly, these PAMPs and inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and CCL2, are increased in the sera of humans after alcohol exposure and exposure to LPS33,34. In addition, alcohol intake increases serum levels of lipoteichoic acid (LTA) and flagellin, and it sensitizes LTA and flagellin to TLR2 and TLR5, respectively, leading to enhanced TNF-α production and liver injury in a mouse model of ALD35. More intriguingly, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is also triggered by sterile inflammatory responses, and a recent interesting study in humans suggests that the presence of Klebsiella pneumoniae in the gut microbiome might be one of the causes of NAFLD because of its ability to produce alcohol, thereby increasing the alcohol concentration in the blood36.

Inter-organ cross-talk in ALD

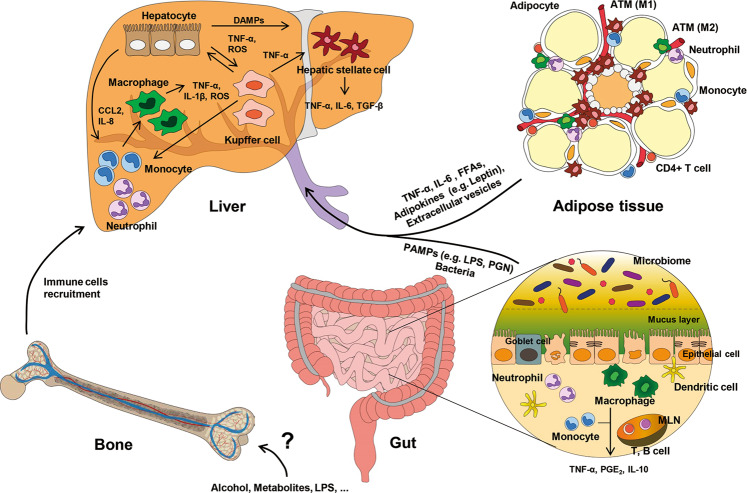

Several lines of evidence have reported cross-talk between the liver and other organs, such as adipose tissue, the gut, and bone marrow (BM, Fig. 1). For example, metabolic and genetic changes in adipocytes and enterocytes affect steatosis and inflammation of the liver. In addition, altered gene expression in hepatocytes and non-parenchymal cells in the liver influences adipogenesis, lipolysis, and inflammation of adipose tissue, the gut, or BM.

Fig. 1. Inter-organ cross-talk in alcoholic liver disease.

Alcohol consumption induces lipolysis in adipocytes and inflammatory responses in adipose immune cells, including macrophages, which in turn lead to the release of free fatty acids (FFAs), adipokines (e.g., leptin), and cytokines (e.g., TNF-α and IL-6) into the portal circulation. In addition, alcohol intake alters the gut microbiome composition and increases the permeability of intestinal bacteria and their metabolites through broken barriers of epithelial cells in the gut, thus leading to translocation of bacteria and inflammatory cells in the liver. Therefore, metabolic and immunogenic factors, including DAMPs and PAMPs, from adipose tissue and the gut enter the liver, affecting hepatocytes and non-parenchymal cells in the liver to recruit pro-inflammatory immune cells from the bone marrow. Taken together, inter-organ cross-talk between the liver and other organs plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of ALD.

The adipose tissue-liver axis in ALD

Metabolic effects of alcohol in adipose tissue

Anatomically, adipose tissue consists of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) and subcutaneous adipose tissue37. VAT is mainly present within the abdominal cavity, and visceral fat venous blood is drained directly into the liver through the portal vein. Thus, abnormal metabolic pathways and inflammation in VAT are implicated in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndromes, including obesity, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and NAFLD38. White adipocytes, which account for most adipocytes, function to store energy as triglycerides in large lipid droplets and release adipokines and cytokines for metabolic and endocrine activities. In contrast, brown adipocytes contribute to thermogenesis through the high expression of uncoupling protein 1 in mitochondria39. Recent studies have suggested that chronic alcohol consumption is inversely correlated with fat accumulation in adipose tissue. In mice and rats, chronic alcohol exposure stimulates adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL)-mediated lipolysis in adipose tissue, leading to the release of free fatty acids (FFAs) and a decrease in the epididymal adipose tissue mass and adipocyte size40. Moreover, binge drinking or chronic alcohol consumption impairs insulin sensitivity, thus resulting in increased lipolysis and decreased lipogenesis41. The expression of lipogenic enzymes, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, and CCAAT enhancer-binding protein α, is also downregulated in white adipose tissue after chronic alcohol intake40. Interestingly, alcohol can be metabolized in adipose tissue in humans and rodents owing to the expression of CYP2E1 and ALDH42. In adipose tissue, increased CYP2E1 expression owing to chronic alcohol intake decreases the GSH/GSSG ratio, induces oxidative stress through ROS production, and inhibits adiponectin secretion42. Leptin (an energy expenditure hormone) is also known to be related to alcohol intake, but its expression depends on the amount and duration of alcohol consumption in ALD patients and a rodent model43,44.

Inflammation in adipose tissue

Chronic alcohol consumption stimulates the secretion of several cytokines and chemokines, thereby inducing inflammation in adipose tissue. In alcoholic patients, the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6 and TNF-α) and chemokines (e.g., CCL2), is upregulated in adipose tissue45,46. IL-6 expression increases in all stages of ALD, whereas increased expression of TNF-α is only observed in patients with alcoholic steatosis and alcoholic hepatitis37. Rodent models also show increased expression of inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α, IL-6, CCL2, and IFN-γ, in adipose tissue46. In adipose tissue inflammation, the number of macrophages is increased (up to 4–50%), in which adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs) are divided into M1 and M2 types47. M1 macrophages exist as crown-like structures around dying adipocytes and classically express inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), whereas the M2 type is an alternatively activated cell type that produces anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10, IL-4, and arginase 1. In a normal state, most ATMs exist as the M2 type; however, in a state of alcohol consumption, these cells shift to the M1 type, expressing CD11c and producing inflammatory cytokines or causing infiltration of M1 macrophages in a CCL2-dependent manner46. In addition, binge alcohol intake increases the infiltration of neutrophils with neutrophil-attracting chemokines, thereby inducing tissue damage in mice48. In contrast, IL-10 levels in adipose tissue are increased in acute alcoholic hepatitis, suggesting that some cells possess anti-inflammatory functions that regulate the immune system49.

Adipocyte death

Adipocyte death is induced by chronic inflammation and oxidative stress. The ATMs surround dead adipocytes in crown-like structures, and they produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 to facilitate phagocytosis or scavenging of adipocytes50. Moreover, it has been reported that chronic ethanol consumption increases Bid-mediated apoptosis in adipocytes, whereas CYP2E1 deficiency results in decreased expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and CCL2 and reduced adipocyte apoptosis in mice46, suggesting that adipose tissue inflammation is dependent on CYP2E1-mediated alcohol metabolism. Thus, CYP2E1 might be a good therapeutic target in adipose tissue.

Cross-talk between the liver and adipose tissue

Increased amounts of circulating FFAs caused by lipolysis in adipocytes contribute to lysosomal destabilization in hepatocytes, leading to TNF-α production and hepatic de novo lipogenesis through transcription of SREBP1c51. Moreover, among adipokines, adiponectin in humans and rodents contributes to not only the oxidization of fatty acids in hepatocytes but also the reduction in TNF-α and IL-10 production in Kupffer cells, thereby alleviating liver steatosis and inflammation52. The leptin from adipose tissue induces hepatic inflammation and fibrogenic responses by activating HSCs and Kupffer cells, and Kupffer cells increase TNF-α production through the P38 and JNK pathways53,54. In chronic alcohol consumption, as observed in alcoholic patients and mouse models, the production of adiponectin is decreased, but leptin production is increased, resulting in damage to hepatocytes by high concentrations of TNF-α55. Furthermore, adipose tissue influences alcoholic liver injury by modulating the cargo of the secreted EVs trafficking to the liver via the secretome56.

The gut–liver axis in ALD

Gut microbiota and the immune system

In addition to energy absorption, the gut has a well-established immune system that plays a role in homeostasis. Mechanochemically, the surface of enterocytes in the small intestine consists of microvilli coated with a glycocalyx of mucin, which produces diverse enzymes for the defense against antigens or pathogens from the lumen57. The intestinal lamina propria consists of various types of immune cells and lymphatic tissues. For example, gut-associated lymphoid tissue and mesenteric lymph nodes, including Peyer’s patches, are composed of numerous T cells and B cells, and naive lymphocytes are primed by pathogens or antigen-presenting cells that are external to the immune response58. Several subsets of dendritic cells regulate T-cell stimulation and suppression by recognizing pathogens through TLR signaling; in addition, macrophages are involved in the phagocytosis of dead cells and induce proliferation of regulatory T cells by producing IL-1057,59. Interestingly, the gut microbiome coexists with its host; there are over 100 trillion microorganisms in the human gastrointestinal tract, and the microbiome not only comprises bacteria, but also fungi, archaea, protists, and viruses60. The microbiome is established by the influence of environmental conditions and food consumption after birth and is important for immune and metabolic homeostasis of the host. However, the composition of the microbiome changes in ALD61.

Metabolic effects of alcohol on gut microbiota and immunity

Ingested alcohol is absorbed and diffused in the gastrointestinal tract, where the stomach and the proximal small intestine are responsible for ~20% and 70% of its absorption, respectively62. Among alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs), ADH1A is expressed in the small intestine and enables alcohol metabolism, whereas the other isoenzymes have a role in vitamin A (retinol) metabolism, which is essential for intestinal epithelial proliferation or differentiation63. However, high concentrations of alcohol and chronic absorption are metabolized by CYP2E1, and oxidative stress and byproducts caused by alcohol metabolism alter the intestinal tight junction proteins (e.g., occludin and zonula occludens-1) and adherent junction proteins (e.g., β-catenin and E-cadherin), which interconnect the epithelial cells that have a role in intestinal barrier integrity63–65. In addition, CYP2E1-mediated alcohol metabolism increases intestinal permeability by inducing the expression of circadian clock proteins such as circadian locomotor output cycles kaput and period circadian clock 266. Furthermore, chronic alcohol consumption destroys the intestinal epithelial barrier, leading to changes, such as overgrowth and dysbiosis, in the intestinal microbiome of rodents and patients. Alcohol-mediated dysbiosis increases the levels of unconjugated bile acids in the gut, which reduces farnesoid X receptor activity and fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-15 expression in enterocytes, leading to increased bile acid concentration in the blood through upregulated CYP7A1 expression in hepatocytes67. However, treatment with the FXR agonist, fexaramine, or overexpression of FGF-15 leads to recovery of the gut barrier and attenuates ALD67.

Overgrowth of gram-negative bacteria owing to alcohol consumption induces endotoxin production and release in the blood of rodents and human patients68. In addition, LPS enhances intestinal permeability by producing nitric oxide by autocrine signaling, thereby activating myosin light chain kinase and the expression of TLR4 and CD14 in enterocytes69,70. In alcohol-fed mice, bacteria of the phyla Verrucomicrobia and Bacteroidetes increase, whereas those of the phylum Firmicutes decrease71. In alcoholic patients, Proteobacteria and Firmicute phyla increase; however, this increase depends on the stage of liver disease61,72. A recent study reported that the numbers of cytolysin-positive Enterococcus faecalis correlate with the severity of alcoholic hepatitis and mortality73. Interestingly, intestinal overgrowth of K. pneumoniae causes fatty liver disease because these bacteria produce alcohol, in the absence of alcohol consumption74. Moreover, populations of fungi, as well as bacteria, are increased in the gut owing to alcohol consumption and translocate to the liver to induce inflammation through the β-glucan-CLEC7A axis75.

Inflammation in the gut

Increasing intestinal permeability leads to translocation of bacteria and PAMPs to the portal blood and exposure to the intestinal immune system, wherein they stimulate myeloid cells and induce systemic inflammation76. However, in ALD, the exact underlying mechanisms of gut inflammation by alcohol are still unclear. In mice with chronic exposure to alcohol, the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and iNOS, increases in the distal ileum, and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-11 also increases significantly77. In an “alcohol combined with burn injury” model, intestinal macrophages or monocytes increase the production of TNF-α, prostaglandin E2, and IL-10 and decrease the expression of MHC class II and antigen presentation78. In addition, in this model, increased IL-18 has a critical role in the recruitment and activation of neutrophils in the damaged intestines of rats79. Regarding adaptive immune responses, acute alcohol administration to mice depletes T cells and B cells in the MLN80,81. IL-12, which has key roles in Th1 differentiation and IFN-γ production, is reduced in rat T cells after alcohol intoxication and burn injury82.

Cross-talk between the liver and gut

In ALD, gut-liver cross-talk is mainly caused by increased gut permeability, leading to the entry of PAMPs (e.g., LPS) into the liver through the portal circulation. LPS binds to TLR4 in combination with CD14, MD-2, and LPS-binding protein, and its signal is delivered by the recruitment of adapter molecules, such as MyD88 and TRIF, in Kupffer cells and macrophages83. MyD88-mediated NF-kB activation produces pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) and the chemokine CCL2, whereas the TRIF pathway induces the production of type-I interferons84. Thus, both TLR4 and CD14 are considered therapeutic targets for ALD. Moreover, TLR4 is expressed not only in immune cells but also in hepatocytes and HSCs. In hepatocytes, TLR4-LPS activates the NF-kB pathway and pro-inflammatory signaling, leading to increased expression of SREBP1c that further results in steatosis or hepatic injury55. In response to LPS, HSCs release pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8), chemokines (e.g., CCL2, ICAM-1, RANTES, and CCR5) and adhesion molecules84. Furthermore, TNF-α production in Kupffer cells and the recruitment of immune cells by LPS/TLR4 activate HSCs and induce liver fibrosis by producing TGF-β and extracellular matrix85.

The BM–liver axis in ALD

Cross-talk between the liver and BM

In addition to tissue-resident immune cells, such as Kupffer cells, most inflammatory cells are derived from the BM in alcoholic inflammation of adipose tissue, the gut, and the liver. The BM is thought to be an immunoregulatory organ that has a role not only in hematopoiesis but also in immune responses86. Thus, inflammatory cells mature and proliferate in the BM and egress into the bloodstream by the gradients of cytokines and chemokines, such as CXCL12-CXCR4, CXCL1-CXCR2, and CCL2-CCR287,88. Clinical and experimental studies have shown that autologous or allogenic BM cell transplantation is effective for liver cirrhosis and fibrosis in patients and mice, respectively, in which migrated BM cells improve impaired liver functions in patients or stimulate IL-10 production in Gr1+CD11b+ cells in mice89,90. However, autologous BM cell transplantation did not show beneficial effects in liver function or IL-10 production in a patient with alcoholic cirrhosis90, suggesting that chronic alcohol consumption might affect BM cells. Recently, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), a glycoprotein that differentiates and matures stem cells into granulocytes in the BM, has emerged as a treatment candidate for alcoholic hepatitis in several countries91–94. Clinical and experimental studies have shown that G-CSF treatment improves alcoholic hepatitis by migrating CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells and stimulating hepatocyte regeneration in patients and mice, suggesting a novel therapeutic effect of G-CSF on alcoholic hepatitis91,95.

In contrast, the effects of alcohol intake on the BM have yet to be clearly elucidated. Intriguingly, our recent study suggests that BM-derived monocytes can be differentiated into F4/80high Kupffer-like cells in a CX3CR1-dependent manner and have pro-inflammatory functions in ALD96. Similarly, other studies have demonstrated that monocytes are recruited by liver HSCs and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, and they differentiate into monocyte-derived Kupffer cells through the NOTCH-BMP pathway in certain situations97,98. These studies suggest that BM-derived macrophages may have a role in ALD through the differentiation of Kupffer-like cells. Although the exact functions of such macrophages are not yet clear, they may have various functions depending on multiple subtypes of macrophages in the BM and various conditions in ALD. Given that alcohol metabolism occurs within the BM, clarification of alcohol-metabolizing cells and their roles in ALD are likely to be of vital importance in the treatment of ALD. Consequently, further studies on this subject are of the utmost importance.

Future perspectives

Although the best way to prevent further progression of ALD is to abstain from consuming alcohol, current therapies for ALD focus on the stages of disease severity and mostly depend on steroid treatments. However, we are still struggling to use such treatment strategies in ALD patients who consume high amounts of alcohol and are resistant to medication. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop alternative approaches to treat ALD. Generally, alcohol metabolism is considered to occur in the liver, but recent studies have demonstrated that other organs, including adipose tissue and intestine, can metabolize alcohol partially owing to the expression of ADHs and CYP2E1. In addition, mechanical pathways related to oxidative stress-mediated inflammation and injury are well known to occur in adipose tissue and the gut. Furthermore, organ cross-talk is triggered by the entry of inflammatory cytokines and molecules, such as adipokines, DAMPs, and PAMPs, as well as the migration of pro-inflammatory cells into the liver, which further exacerbates ALD by activating hepatic immune cells and inducing hepatocyte injury. As a result, the entire paradigm of ALD originates not only due to liver injury but also due to cross-talk with other organs. Therefore, using a single factor in a specific organ as a therapeutic target may be ineffective, and combination therapy aimed at multiple organs is likely required for the treatment of ALD.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korean government (MEST) (2018R1A2A1A05077608), Korea Mouse Phenotyping Project (2014M3A9D5A01073556), and the Intelligent Synthetic Biology Center of Global Frontier Project (2011–0031955) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bajaj JS. Alcohol, liver disease and the gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019;16:235–246. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seo W, Jeong WI. Hepatic non-parenchymal cells: master regulators of alcoholic liver disease? World J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1348–1356. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i4.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suh YG, Jeong WI. Hepatic stellate cells and innate immunity in alcoholic liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2543–2551. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i20.2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szabo G. Gut-liver axis in alcoholic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:30–36. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao B, Ahmad MF, Nagy LE, Tsukamoto H. Inflammatory pathways in alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2019;70:249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller S, et al. Carcinogenic etheno DNA adducts in alcoholic liver disease: correlation with cytochrome P-4502E1 and fibrosis. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2018;42:252–259. doi: 10.1111/acer.13546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu Y, Cederbaum AI. CYP2E1 and oxidative liver injury by alcohol. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;44:723–738. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ge X, et al. High mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) participates in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease (ALD) J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:22672–22691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.552141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai Y, et al. Mitochondrial DNA-enriched microparticles promote acute-on-chronic alcoholic neutrophilia and hepatotoxicity. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e92634. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.92634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iracheta-Vellve A, et al. Inhibition of sterile danger signals, uric acid and ATP, prevents inflammasome activation and protects from alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. J. Hepatol. 2015;63:1147–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petrasek J, et al. IL-1 receptor antagonist ameliorates inflammasome-dependent alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:3476–3489. doi: 10.1172/JCI60777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsova P, et al. Extracellular vesicles in liver pathobiology: small particles with big impact. Hepatology. 2016;64:2219–2233. doi: 10.1002/hep.28814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eguchi A, et al. Extracellular vesicles released by hepatocytes from gastric infusion model of alcoholic liver disease contain a MicroRNA barcode that can be detected in blood. Hepatology. 2017;65:475–490. doi: 10.1002/hep.28838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saha B, Momen-Heravi F, Kodys K, Szabo G. MicroRNA cargo of extracellular vesicles from alcohol-exposed monocytes signals naive monocytes to differentiate into M2 macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:149–159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.694133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhir A, et al. Mitochondrial double-stranded RNA triggers antiviral signalling in humans. Nature. 2018;560:238–242. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0363-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, J. H. et al. Mitochondrial double-stranded RNA in exosome promotes interleukin-17 production through toll-like receptor 3 in alcoholic liver injury. Hepatology (2019) [Ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Seo W, et al. Exosome-mediated activation of toll-like receptor 3 in stellate cells stimulates interleukin-17 production by gammadelta T cells in liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2016;64:616–631. doi: 10.1002/hep.28644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byun JS, Suh YG, Yi HS, Lee YS, Jeong WI. Activation of toll-like receptor 3 attenuates alcoholic liver injury by stimulating Kupffer cells and stellate cells to produce interleukin-10 in mice. J. Hepatol. 2013;58:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe A, et al. Apoptotic hepatocyte DNA inhibits hepatic stellate cell chemotaxis via toll-like receptor 9. Hepatology. 2007;46:1509–1518. doi: 10.1002/hep.21867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seo W, et al. ALDH2 deficiency promotes alcohol-associated liver cancer by activating oncogenic pathways via oxidized DNA-enriched extracellular vesicles. J. Hepatol. 2019;71:1000–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saha B, et al. Extracellular vesicles from mice with alcoholic liver disease carry a distinct protein cargo and induce macrophage activation through heat shock protein 90. Hepatology. 2018;67:1986–2000. doi: 10.1002/hep.29732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verma VK, et al. Alcohol stimulates macrophage activation through caspase-dependent hepatocyte derived release of CD40L containing extracellular vesicles. J. Hepatol. 2016;64:651–660. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeong WI, et al. Paracrine activation of hepatic CB1 receptors by stellate cell-derived endocannabinoids mediates alcoholic fatty liver. Cell Metab. 2008;7:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi WM, et al. Glutamate signaling in hepatic stellate cells drives alcoholic steatosis. Cell Metab. 2019;30:877–889 e877. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsukamoto H, Lu SC. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver injury. FASEB J. 2001;15:1335–1349. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0650rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee YS, Jeong WI. Retinoic acids and hepatic stellate cells in liver disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;27:75–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.07007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yi HS, et al. Alcohol dehydrogenase III exacerbates liver fibrosis by enhancing stellate cell activation and suppressing natural killer cells in mice. Hepatology. 2014;60:1044–1053. doi: 10.1002/hep.27137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeong WI, Park O, Radaeva S, Gao B. STAT1 inhibits liver fibrosis in mice by inhibiting stellate cell proliferation and stimulating NK cell cytotoxicity. Hepatology. 2006;44:1441–1451. doi: 10.1002/hep.21419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeong WI, Park O, Gao B. Abrogation of the antifibrotic effects of natural killer cells/interferon-gamma contributes to alcohol acceleration of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:248–258. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeong WI, et al. Suppression of innate immunity (natural killer cell/interferon-gamma) in the advanced stages of liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2011;53:1342–1351. doi: 10.1002/hep.24190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee YS, et al. Blockade of retinol metabolism protects T cell-induced hepatitis by increasing migration of regulatory T cells. Mol. Cells. 2015;38:998–1006. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2015.0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bala S, Marcos M, Gattu A, Catalano D, Szabo G. Acute binge drinking increases serum endotoxin and bacterial DNA levels in healthy individuals. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e96864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michelena J, et al. Systemic inflammatory response and serum lipopolysaccharide levels predict multiple organ failure and death in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 2015;62:762–772. doi: 10.1002/hep.27779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gustot T, et al. Differential liver sensitization to toll-like receptor pathways in mice with alcoholic fatty liver. Hepatology. 2006;43:989–1000. doi: 10.1002/hep.21138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan J, et al. Fatty liver disease caused by high-alcohol-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Cell Metab. 2019;30:1172. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parker R, Kim SJ, Gao B. Alcohol, adipose tissue and liver disease: mechanistic links and clinical considerations. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;15:50–59. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kusminski CM, Bickel PE, Scherer PE. Targeting adipose tissue in the treatment of obesity-associated diabetes. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016;15:639–660. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fedorenko A, Lishko PV, Kirichok Y. Mechanism of fatty-acid-dependent UCP1 uncoupling in brown fat mitochondria. Cell. 2012;151:400–413. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhong W, et al. Chronic alcohol exposure stimulates adipose tissue lipolysis in mice: role of reverse triglyceride transport in the pathogenesis of alcoholic steatosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2012;180:998–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindtner C, et al. Binge drinking induces whole-body insulin resistance by impairing hypothalamic insulin action. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:170ra114. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang H, et al. Ethanol-induced oxidative stress via the CYP2E1 pathway disrupts adiponectin secretion from adipocytes. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2012;36:214–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01607.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Obradovic T, Meadows GG. Chronic ethanol consumption increases plasma leptin levels and alters leptin receptors in the hypothalamus and the perigonadal fat of C57BL/6 mice. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2002;26:255–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalafateli M, et al. Adipokines levels are associated with the severity of liver disease in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3020–3029. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i10.3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Voican CS, et al. Alcohol withdrawal alleviates adipose tissue inflammation in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Liver Int. 2015;35:967–978. doi: 10.1111/liv.12575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sebastian BM, et al. Identification of a cytochrome P4502E1/Bid/C1q-dependent axis mediating inflammation in adipose tissue after chronic ethanol feeding to mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:35989–35997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.254201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weisberg SP, et al. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qin Y, et al. Adipose inflammation and macrophage infiltration after binge ethanol and burn injury. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2014;38:204–213. doi: 10.1111/acer.12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naveau S, et al. Harmful effect of adipose tissue on liver lesions in patients with alcoholic liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2010;52:895–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Russo L, Lumeng CN. Properties and functions of adipose tissue macrophages in obesity. Immunology. 2018;155:407–417. doi: 10.1111/imm.13002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feldstein AE, et al. Free fatty acids promote hepatic lipotoxicity by stimulating TNF-alpha expression via a lysosomal pathway. Hepatology. 2004;40:185–194. doi: 10.1002/hep.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mandal P, Pritchard MT, Nagy LE. Anti-inflammatory pathways and alcoholic liver disease: role of an adiponectin/interleukin-10/heme oxygenase-1 pathway. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1330–1336. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i11.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ikejima K, et al. Leptin augments inflammatory and profibrogenic responses in the murine liver induced by hepatotoxic chemicals. Hepatology. 2001;34:288–297. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen J, Sakaida I, Uchida K, Terai S, Okita K. Leptin enhances TNF-alpha production via p38 and JNK MAPK in LPS-stimulated Kupffer cells. Life Sci. 2005;77:1502–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagy LE. The role of innate immunity in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Res. 2015;37:237–250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCullough RL, et al. Anaphylatoxin receptors C3aR and C5aR1 are important factors that influence the impact of ethanol on the adipose secretome. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2133. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mowat AM, Agace WW. Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:667–685. doi: 10.1038/nri3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Habtezion A, Nguyen LP, Hadeiba H, Butcher EC. Leukocyte trafficking to the small intestine and colon. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:340–354. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Okumura R, Takeda K. Maintenance of gut homeostasis by the mucosal immune system. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2016;92:423–435. doi: 10.2183/pjab.92.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thursby E, Juge N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J. 2017;474:1823–1836. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mutlu EA, et al. Colonic microbiome is altered in alcoholism. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G966–G978. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00380.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levitt MD, et al. Use of measurements of ethanol absorption from stomach and intestine to assess human ethanol metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:G951–G957. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.4.G951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elamin EE, Masclee AA, Dekker J, Jonkers DM. Ethanol metabolism and its effects on the intestinal epithelial barrier. Nutr. Rev. 2013;71:483–499. doi: 10.1111/nure.12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Forsyth CB, Voigt RM, Keshavarzian A. Intestinal CYP2E1: a mediator of alcohol-induced gut leakiness. Redox Biol. 2014;3:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cho, Y. E. et al. Fructose promotes leaky gut, endotoxemia, and liver fibrosis through ethanol-inducible cytochrome P450-2E1-mediated oxidative and nitrative stress. Hepatology (2019) [Ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Forsyth CB, et al. Role for intestinal CYP2E1 in alcohol-induced circadian gene-mediated intestinal hyperpermeability. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2013;305:G185–G195. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00354.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tripathi A, et al. The gut-liver axis and the intersection with the microbiome. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;15:397–411. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0011-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Parlesak A, Schafer C, Schutz T, Bode JC, Bode C. Increased intestinal permeability to macromolecules and endotoxemia in patients with chronic alcohol abuse in different stages of alcohol-induced liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2000;32:742–747. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80242-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gu L, et al. Berberine ameliorates intestinal epithelial tight-junction damage and down-regulates myosin light chain kinase pathways in a mouse model of endotoxinemia. J. Infect. Dis. 2011;203:1602–1612. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guo S, Al-Sadi R, Said HM, Ma TY. Lipopolysaccharide causes an increase in intestinal tight junction permeability in vitro and in vivo by inducing enterocyte membrane expression and localization of TLR-4 and CD14. Am. J. Pathol. 2013;182:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yan AW, et al. Enteric dysbiosis associated with a mouse model of alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53:96–105. doi: 10.1002/hep.24018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen Y, et al. Characterization of fecal microbial communities in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;54:562–572. doi: 10.1002/hep.24423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Duan Y, et al. Bacteriophage targeting of gut bacterium attenuates alcoholic liver disease. Nature. 2019;575:505–511. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1742-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yuan J, et al. Fatty liver disease caused by high-alcohol-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Cell Metab. 2019;30:675–688 e677. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang AM, et al. Intestinal fungi contribute to development of alcoholic liver disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2017;127:2829–2841. doi: 10.1172/JCI90562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leclercq S, De Saeger C, Delzenne N, de Timary P, Starkel P. Role of inflammatory pathways, blood mononuclear cells, and gut-derived bacterial products in alcohol dependence. Biol. Psychiatry. 2014;76:725–733. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fleming S, et al. Pro- and anti-inflammatory gene expression in the murine small intestine and liver after chronic exposure to alcohol. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2001;25:579–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Choudhry MA, et al. Impaired intestinal immunity and barrier function: a cause for enhanced bacterial translocation in alcohol intoxication and burn injury. Alcohol. 2004;33:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Akhtar S, Li X, Chaudry IH, Choudhry MA. Neutrophil chemokines and their role in IL-18-mediated increase in neutrophil O2- production and intestinal edema following alcohol intoxication and burn injury. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G340–G347. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00044.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sibley DA, Fuseler J, Slukvin I, Jerrells TR. Ethanol-induced depletion of lymphocytes from the mesenteric lymph nodes of C57B1/6 mice is associated with RNA but not DNA degradation. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 1995;19:324–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Choudhry MA, Fazal N, Goto M, Gamelli RL, Sayeed MM. Gut-associated lymphoid T cell suppression enhances bacterial translocation in alcohol and burn injury. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G937–G947. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00235.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li X, Chaudry IH, Choudhry MA. ERK and not p38 pathway is required for IL-12 restoration of T cell IL-2 and IFN-gamma in a rodent model of alcohol intoxication and burn injury. J. Immunol. 2009;183:3955–3962. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jarvelainen HA, et al. Promoter polymorphism of the CD14 endotoxin receptor gene as a risk factor for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:1148–1153. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Guo J, Friedman SL. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in liver injury and hepatic fibrogenesis. Fibrogenes. Tissue Repair. 2010;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Seki E, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat. Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhao E, et al. Bone marrow and the control of immunity. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2012;9:11–19. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2011.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shi C, Pamer EG. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:762–774. doi: 10.1038/nri3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Soehnlein O, Steffens S, Hidalgo A, Weber C. Neutrophils as protagonists and targets in chronic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017;17:248–261. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Terai S, et al. Improved liver function in patients with liver cirrhosis after autologous bone marrow cell infusion therapy. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2292–2298. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Suh YG, et al. CD11b(+) Gr1(+) bone marrow cells ameliorate liver fibrosis by producing interleukin-10 in mice. Hepatology. 2012;56:1902–1912. doi: 10.1002/hep.25817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Spahr L, et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor induces proliferation of hepatic progenitors in alcoholic steatohepatitis: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2008;48:221–229. doi: 10.1002/hep.22317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cho Y, et al. Efficacy of granulocyte colony stimulating factor in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis with partial or null response to steroid (GRACIAH trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19:696. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-3092-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shasthry SM, Sharma MK, Shasthry V, Pande A, Sarin SK. Efficacy of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in the management of steroid-nonresponsive severe alcoholic hepatitis: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 2019;70:802–811. doi: 10.1002/hep.30516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Singh V, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in severe alcoholic hepatitis: a randomized pilot study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1417–1423. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yannaki E, et al. G-CSF-primed hematopoietic stem cells or G-CSF per se accelerate recovery and improve survival after liver injury, predominantly by promoting endogenous repair programs. Exp. Hematol. 2005;33:108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lee YS, et al. CX3CR1 differentiates F4/80(low) monocytes into pro-inflammatory F4/80(high) macrophages in the liver. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:15076. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33440-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bonnardel J, et al. Stellate cells, hepatocytes, and endothelial cells imprint the kupffer cell identity on monocytes colonizing the liver macrophage niche. Immunity. 2019;51:638–654 e639. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sakai M, et al. Liver-derived signals sequentially reprogram myeloid enhancers to initiate and maintain kupffer cell identity. Immunity. 2019;51:655–670 e658. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]