Abstract

Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC) represents the most common form of all cancers. BCC is characteristically surrounded by a fibromyxoid stroma. Previous studies have suggested a shift towards a Th2 response, an increase in T regulatory lymphocytes and the presence of cancer-associated fibroblasts in the BCC tumor microenvironment. In this study, we aimed to further characterize the BCC tumor microenvironment in detail by analyzing BCC RNA-Sequencing data and correlating it with clinically-relevant features via in silico RNA deconvolution. Using immune cell type deconvolution by CIBERSORT, we have identified a brisk lymphocytic infiltration, and more abundant macrophages in BCC tumors compared to normal skin. Using cell type enrichment by xCell, we confirmed the observed immune infiltration in BCC tumors and compared them to normal skin. We observed a shift towards Th2 immunity in advanced and vismodegib-resistant tumors. Tumoral inflammation induced by macrophage activity was associated with advanced BCCs, while lymphocytic infiltration was most significant in non-advanced tumors, likely related to an adaptive anti-tumoral response. In advanced and vismodegib-resistant BCCs, mesenchymal stem cell-like properties were observed. Particularly in vismodegib-resistant BCCs, fibroblasts and adipocytes were found at high number, which ultimately may contribute to the decreased drug delivery to the tumor. In conclusion, this study has revealed notable BCC tumor microenvironment findings associated with important clinical features. Microenvironment-altering agents may be used locally for “routine” BCCs and systematically for advanced or resistant BCCs.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12079-020-00563-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC), Tumor microenvironment, xCell, CIBERSORT, Vismodegib

Background

Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer in humans (Rogers et al. 2010). The lifetime risk of developing a BCC is around 30% in fair-skinned individuals (Fitzpatrick phototypes I-III) (Miller and Weinstock 1994). It is well established that constitutive activation of the Sonic hedgehog (Shh) pathway is essential in BCC tumorigenesis in both sporadic and familial forms (Rubin et al. 2005). Recently, small molecules inhibiting SMO (Smoothened) in the Shh pathway, namely vismodegib and sonidegib, have received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for locally advanced and metastatic BCCs (Sekulic et al. 2012; Migden et al. 2015). However, for most patients, these molecules do not lead to complete clinical response and their use is limited by severe side effects (Xie and Lefrancois 2018). Resistance, both primary and secondary, also occurs via Shh-mediated alterations from either additional SMO mutations or mutations in genes downstream of SMO in the Shh pathway (Sharpe et al. 2015; Atwood et al. 2015). Recently, a study in a mouse model discovered (Biehs et al. 2018) that residual BCC cells can switch their gene expression profile towards a stem cell-like phenotype and, thus, become resistant to vismodegib (Biehs et al. 2018).

Most BCC tumors develop a surrounding fibromyxoid stroma. It likely provides a permissive tumor microenvironment by protecting the tumor from the immune system (Bertheim et al. 2004). Indeed, an increased stromal response generated by the tumor and a relative local immunosuppression in the host were observed in BCCs with high-risk histopathological subtypes (Kaur et al. 2006). In one study using immunohistochemistry, the authors found that in BCC tumors, Foxp3+ T regulatory lymphocytes (Treg cells) formed peritumoral aggregates (Kaporis et al. 2007). Foxp3+ Treg cells represented up to 45% of the CD4+ T lymphocytes surrounding a BCC, and are thought to contribute to a local immunosuppressive environment conducive to BCC growth (Omland et al. 2016). Using T cell receptor high-throughput sequencing, no clonal tumor-specific tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte populations were identified in BCC (Omland et al. 2017a). Moreover, cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10 were more abundant in BCC compared to normal skin, consistent with a shift towards a Th2 inflammatory response (Kaporis et al. 2007).

Conventional techniques to quantify cell populations and heterogeneity are tedious and prone to artefacts (Shen-Orr and Gaujoux 2013). Gene expression profiles, especially from RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq), have been used to estimate the composition of a mixed tumor when pure cell line RNA-Seq data are available; this process is termed RNA deconvolution (Shen-Orr and Gaujoux 2013). RNA deconvolution has been used to identify leukocyte subsets as prognostic biomarkers in different cancers (Gentles et al. 2015). One such RNA deconvolution algorithm, CIBERSORT, uses support vector regression to estimate immune cell abundance (Newman et al. 2015). We have recently found that CIBERSORT-determined immune microenvironment features, in particular neutrophil infiltration and NK T cell abundance, correlate with disease progression in cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) (Lefrancois et al. 2018). Another in silico method, xCell, determines a cell type enrichment from 64 individual cell types using RNA-Seq data (Aran et al. 2017a). This technique was employed to identify the cell type composition of normal tissue adjacent to neoplasms in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project (Aran et al. 2017b). A combination of these methods has successfully determined important elements from the tumoral microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma (Rohr-Udilova et al. 2018).

In this study, by analyzing publicly available whole-genome RNA-Seq data, we explored the BCC tumor microenvironment using CIBERSORT (Newman et al. 2015) to perform immune cell type deconvolution and xCell (Aran et al. 2017a) to determine cell type enrichments. We aimed to understand the correlation between BCC microenvironment and important clinical features.

Methods

Data acquisition

We obtained whole-genome RNA-Seq data on 75 BCC samples and 34 normal skin samples: 13 BCC samples and 8 normal skin samples were from Atwood et al. (Gene Expression Omnibus GEO accession number GSE58377) (Atwood et al. 2015), 51 BCC samples and 26 normal skin samples were from Bonilla et al. (European Genome-phenome Archive EGA accession number EGAS00001001540) (Bonilla et al. 2016), and 11 BCC samples were described by Sharpe et al. (EGA accession number EGAS00001000845) (Sharpe et al. 2015). Available clinical data were limited. A breakdown of samples and clinical data are presented in Table S1.

RNA-Seq analysis

Raw fastq files were curated to remove low quality reads using FastX-Toolkit. Reads were aligned against the hg38 reference human genome using HISAT2 (Kim et al. 2015). Read counts were obtained using htseq-count (Anders et al. 2015) while transcripts per million reads were computed by Cufflinks (Trapnell et al. 2012). The following comparisons were designed: 1) BCCs vs. normal skin, 2) locally advanced and metastatic BCCs vs. routine BCCs, and 3) vismodegib-resistant vs. vismodegib-sensitive BCCs.

Cell-type enumeration using RNA deconvolution

CIBERSORT was used to perform RNA deconvolution using the standard LM22 leukocyte signature matrix obtained from 22 immune pure cell lines (Newman et al. 2015) and 100 permutations. We performed the following analyses in CIBERSORT: all B cells, all CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, Treg cells, all NK T cells, T γδ (gamma delta) cells, total lymphocytes, and total macrophages. Standard CIBERSORT relative scores were considered for primary analyses. For selected analyses, absolute CIBERSORT scores were used to enhance visualization of individual samples (Newman et al. 2015). Cell type abundance scores were obtained using xCell’s standard 64 cell type signatures (Aran et al. 2017a). Significance was assessed using a non-parametric resampling method (Bootstrapping with sample = 100 and number of iterations = 100,000). P-values were calculated by summing the 100,000 comparisons between bootstrapped means, and rendered two-sided. A Bonferroni correction was used to correct for multiple hypothesis testing, separately for CIBERSORT and for xCell analyses. Plots were generated using R package ggplot2 (Wickham 2016).

Results

BCC vs. normal skin

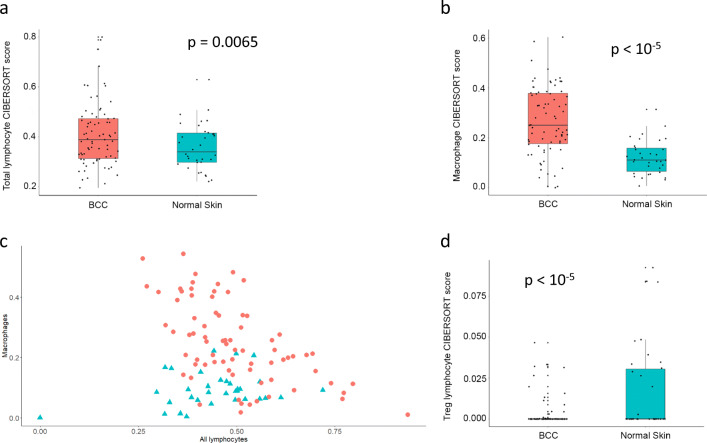

We compared the microenvironment of 75 BCC samples and 34 normal skin samples from three publicly available datasets (Table S1). Using CIBERSORT, we found that in BCC, there is an increased total lymphocytic infiltration compared to normal skin (Fig. 1a; p = 0.0065). Specifically, the number of B lymphocytes was significantly increased in BCC (Figure S1; p = 0.021). We did not observe any notable differences in the amount of CD4+, CD8+ or NK T lymphocytes. In addition, BCC samples had more macrophages compared to normal skin (Fig. 1b; p < 10−5), which may play a role in tumoral inflammation. To account for variable intensities of inflammatory infiltrates between samples, we plotted absolute CIBERSORT scores for macrophages and total lymphocytes. We found that, for BCC samples, lymphocytic and macrophage-driven infiltrates were negatively correlated (Fig. 1c; Spearman’s rho = −0.56; p = 2.6 E-07). Surprisingly we observed higher Treg cell scores in normal skin than in BCC (Fig. 1d; p < 10−5).

Fig. 1.

All BCCs vs. normal skin samples: CIBERSORT. Immune cell fraction obtained in silico using CIBERSORT for all BCC samples (red) and normal skin samples (turquoise). Quartile boxplots are shown along with individual data points. Total lymphocytes (a), total macrophages (b), and regulatory T lymphocytes (Treg cells) (d) are displayed. c Absolute total macrophages and total lymphocytes counts from CIBERSORT for all BCC samples (red circles) and normal skin samples (turquoise triangles) are plotted

Using xCell, we compared cell abundance scores between BCC and normal skin. As a due diligence check, the abundance scores for epidermal keratinocytes were comparable (p = 0.36). We did not find differences in Th1 or Th2 scores (p = 0.38 and p = 0.21, respectively). Instead, higher total CD8+ T lymphocyte score and NK T cell score were found in BCCs (Figure S2A and S2B; p = 0.0064 and p < 10−5). NK T and CD8+ T lymphocytic infiltrates in BCC samples demonstrated a direct correlation (Figure S2C; Spearman’s rho = 0.66; p = 1.5 E-10), suggesting related roles in an anti-tumoral immune response. Different from the previous report (Kaporis et al. 2007), we observed a significantly lower abundance score for immature dendritic cells (iDC) in BCCs (Figure S2D; p < 10−5).

Advanced vs. non-advanced BCCs

Locally advanced and metastatic tumors account for 0.8% and 0.04% of BCCs, respectively (Goldenberg et al. 2016). Together they comprise the advanced BCC tumor group. In general, non-advanced (“routine”) BCCs are commonly managed in outpatient dermatology clinics.

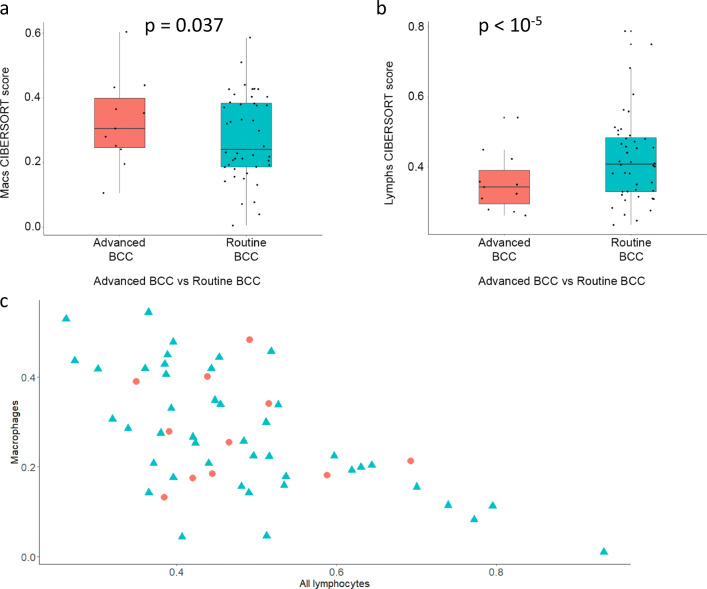

We compared the microenvironment of 11 advanced BCC samples with 44 non-advanced BCC samples (Sharpe et al. 2015; Bonilla et al. 2016). CIBERSORT analysis revealed that, on average, more macrophages (Fig. 2a; p = 0.037) and less lymphocytes (Fig. 2b; p < 10−5) were observed in advanced BCCs, when compared to non-advanced BCC tumors. This suggests that in advanced BCCs a macrophage-heavy tumoral inflammation predominates, rather than an adaptive, lymphocyte-driven anti-tumoral response. These infiltrates remain negatively correlated both in advanced (Fig. 2c; red dots; Spearman’s rho = −0.62; p = 0.048) and in non-advanced (i.e., routine) (Fig. 2c; turquoise triangles; Spearman’s rho = −0.68; p = 1.0 E-06) tumors. There were subgroups of non-advanced BCCs with higher B cell and Treg lymphocyte numbers despite very close mean values and distribution, explaining the statistically significant differences between advanced and routine samples (Figures S3 and S4; p = 0.029 and p < 10−5).

Fig. 2.

Advanced vs. non-advanced (“routine”) BCCs: CIBERSORT. Immune cell fraction obtained in silico using CIBERSORT for advanced BCC samples (red) and routine BCC samples (turquoise). Quartile boxplots are shown along with individual data points. Total macrophages (a) and total lymphocytes (b) are displayed. c Absolute total macrophages and total lymphocytes counts from CIBERSORT for advanced BCCs (red circles) and routine BCCs (turquoise triangles) are plotted

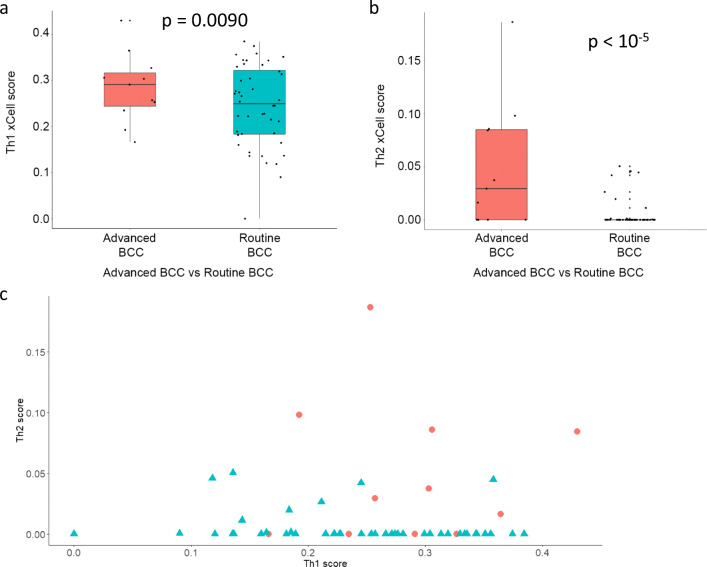

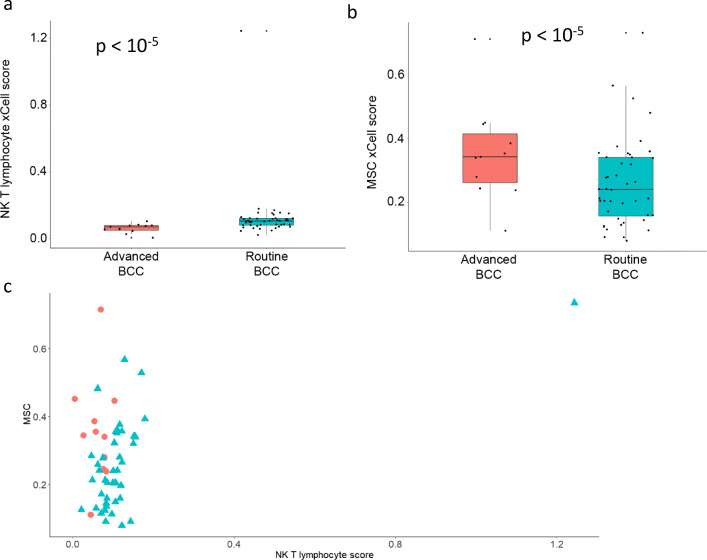

Using xCell, we compared cell abundance scores between advanced and routine BCCs. Again, we found a similar abundance scores of epidermal keratinocytes (p = 1). Th1 and Th2 immune cytokine profile scores were higher in advanced BCCs (Fig. 3a, b; p = 0.0090 and p < 10−5), without a clear relationship on a sample-by-sample basis in advanced tumors (Fig. 3c). In comparison, non-advanced BCCs (i.e., routine) had a higher NK T cell abundance score (Fig. 4a; p < 10−5). Interestingly, the mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) score was greater in advanced BCCs compared to routine BCCs (Fig. 4b; p < 10−5). Individual NK T cell and MSC scores are plotted in Fig. 4c. Thus, given this higher MSC score, advanced BCC cells may exhibit features of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition enabling local invasion and distant metastasis.

Fig. 3.

Advanced vs. non-advanced (“routine”) BCCs: xCell – cytokine scores. Cell abundance enrichment score obtained in silico using xCell for advanced BCC samples (red) and routine BCC samples (turquoise). Quartile boxplots are shown along with individual data points. Th1 immune cytokine (a) and Th2 immune cytokine (b) scores are displayed. c Individual Th1 and Th2 cytokine scores from xCell for advanced BCCs (red circles) and routine BCCs (turquoise triangles) are plotted

Fig. 4.

Advanced vs. non-advanced (“routine”) BCCs: xCell – other parameters. Cell abundance enrichment score obtained in silico using xCell for advanced BCC samples (red) and routine BCC samples (turquoise). Quartile boxplots are shown along with individual data points. NK T lymphocytes (a) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) (b) scores are displayed. c Individual NK T lymphocytes and MSC scores from xCell for advanced BCCs (red circles) and routine BCCs (turquoise triangles) are plotted

Vismodegib-resistant vs. Vismodegib–sensitive BCCs

Vismodegib and sonidegib are FDA-approved Shh inhibitors for advanced BCCs (Sekulic et al. 2012; Migden et al. 2015; Xie and Lefrancois 2018). We compared the microenvironment of 20 vismodegib-resistant BCCs with five vismodegib-sensitive BCC samples (Sharpe et al. 2015; Atwood et al. 2015; Bonilla et al. 2016). FDA-approved vismodegib dosages were used in all three studies (150 mg oral dosing daily). Only Atwood et al. stated that patients were exposed to vismodegib for at least three months prior to sample procurements (Atwood et al. 2015); other studies did not mention sample procurement time or the duration of vismodegib exposure (Sharpe et al. 2015; Bonilla et al. 2016). CIBERSORT analysis documented that a number of cell type patterns differed between vismodegib-resistant and vismodegib-sensitive BCCs. More macrophages (Figure S5A; p < 10−5) and less lymphocytes (Figure S5B; p < 10−5) were observed in vismodegib-resistant BCCs. Analysis of estimated absolute cell counts for these infiltrates did not show significant correlation (Figure S5C; Spearman’s rho = −0.30; p = 0.19). CD8+ T lymphocytes were more abundant in vismodegib-resistant BCCs (Figure S5D; p = 0.00032), while vismodegib-sensitive BCC samples were more enriched with B cells and CD4+ T lymphocytes (Figure S5E and S5F; both p < 10−5). Despite similar mean values, vismodegib-resistant tumors had higher numbers of T γδ lymphocytes (Figure S6; p < 10−5) and vismodegib-sensitive BCCs had more Treg cells (Figure S7; p = 8E-05).

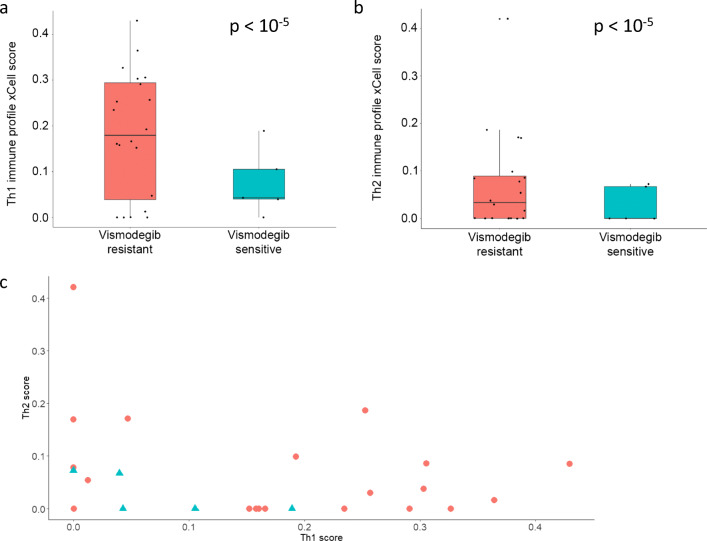

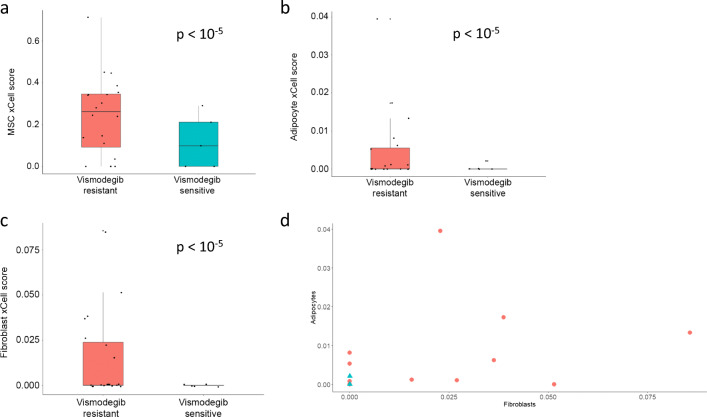

Using xCell, we compared cell abundance score between vismodegib-resistant and vismodegib-sensitive BCCs. We found similar abundance scores of epidermal keratinocytes (p = 0.95). Overall, results based on vismodegib resistance status were reminiscent of those between advanced and non-advanced tumors. In vismodegib-resistant BCCs, Th1 and Th2 immune cytokine profile scores were more pronounced (Fig. 5a, b; both p < 10−5; Fig. 5c for individual Th1 and Th2 scores). Similar to advanced BCCs, the mesenchymal stem cell score was higher in vismodegib-resistant BCCs (Fig. 6a; p < 10−5). Moreover, mature stromal cells such as adipocytes and fibroblasts were more abundant in vismodegib-resistant tumors than in vismodegib-sensitive tumors (Fig. 6b, c; both p < 10−5), a finding not observed in comparison between advanced and routine BCC tumors. Among vismodegib-resistant tumors, analysis of individual scores showed direct correlation for adipocytes and fibroblasts in tumor samples (Fig. 6d; Spearman’s rho = 0.61; p = 1.5 E-10), which is not unexpected given that both cell types represent major stromal components.

Fig. 5.

Vismodegib-resistant vs. vismodegib-sensitive BCCs: xCell – cytokine scores. Cell abundance enrichment score obtained in silico using xCell for vismodegib-resistant (red) vs. -sensitive BCCs (turquoise). Quartile boxplots are shown along with individual data points. Th1 immune cytokine (a) and Th2 immune cytokine (b) scores are displayed. c Individual Th1 and Th2 cytokine scores from xCell for vismodegib-resistant BCCs (red circles) and vismodegib-sensitive BCCs (turquoise triangles) are plotted

Fig. 6.

Vismodegib-resistant vs. vismodegib-sensitive BCCs: xCell – other parameters. Cell abundance enrichment score obtained in silico using xCell for vismodegib-resistant BCC samples (red) and vismodegib-sensitive BCC samples (turquoise). Quartile boxplots are shown along with individual data points. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) (a), adipocytes (b) and fibroblasts (c) scores are displayed. d Individual fibroblasts and adipocytes scores from xCell for vismodegib-resistant BCCs (red circles) and vismodegib-sensitive BCCs (turquoise triangles) are plotted

Discussion

BCC produces both an immunogenic response and a stromal response (Omland 2017). We found that BCC has more immune cell infiltration than normal skin, which is both lymphocyte- and macrophage-driven. The lymphocytic infiltrate in BCCs may have both pro-tumoral and anti-tumoral effects (Omland 2017), with the former role being increasingly recognized. Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-10, are increased in the BCC fibromyxoid stroma (IL-4 and IL-10) (Kaporis et al. 2007). IL-10-producing B cells have been implicated in the proliferation of tumor-associated macrophages, a recognized tumor-promoting event (Mantovani 2011). In breast cancer, an IL-4 driven Th2 response enhanced the pro-tumoral activities of macrophages (DeNardo et al. 2009). It is conceivable that Th2 cytokines are involved in a feedforward loop with B cells, resulting in proliferation and stabilization of tumor-associated macrophages. Surprisingly, we did not observe more Treg cells in BCC compared to normal skin, as opposed to previous studies (Kaporis et al. 2007; Omland et al. 2016). Although the role of Treg cells in immunosuppression is well-known, clinical correlations between Treg infiltration and prognosis has yielded inconsistent results (Givechian et al. 2018). Recently, across all The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) tumors, a 32-gene signature linked increased Treg infiltration with CD8+ abundance, chemosensitivity, and survival, highlighting the mixed results regarding Treg cells in cancer (Givechian et al. 2018). Moreover, we did not observe more immature dendritic cell infiltration in BCCs compared to normal skin, contrary to a prior report (Kaporis et al. 2007).

In advanced BCCs, macrophages were more abundant, and lymphocytes were less prominent. Advanced BCC tumors are often large, ulcerated and rather inflamed (Sekulic et al. 2012). Thus, we expect that a pro-cancer inflammation mediated by tumor-associated macrophages contributes to the pathogenesis in advanced disease without an adaptive lymphocyte-mediated anti-tumoral effect. Similar findings have been observed in other carcinomas, such as colon (Erreni et al. 2011) and lung (Montuenga and Pio 2007). Th1 and Th2 cytokine profiles were both enriched in advanced BCCs. This is consistent with T cell receptor high-throughput sequencing data, which failed to identify any clonal tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte populations (Omland et al. 2017a).

In advanced BCCs and vismodegib-resistant tumors, xCell scores suggested a greater presence of mesenchymal stem cell phenotype. Residual BCC cells in mice treated with vismodegib switch their cell identity towards a stem cell-like profile, reminiscent of cancer stem cells, and become more resistant to vismodegib (Biehs et al. 2018). Similar transcriptional modifications were also observed in human BCC tumors (Biehs et al. 2018). In BCC, this population of cells demonstrate increased Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Sanchez-Danes et al. 2018). Mesenchymal stem cells are considered pro-tumorigenic and are involved in invasion, treatment failure, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis (Chang et al. 2015). In advanced and vismodegib-resistant BCCs, targeting these stem cell properties may provide clinical benefits. Moreover, in vismodegib-resistant BCCs, more mature stromal cells (adipocytes and fibroblasts) were detected, indicating a stronger stromal reaction, which may further protect BCC cells from the immune system. Thus, a tumoral microenvironment characterized by mature stromal cells and by mesenchymal stem cell-like features may contribute to vismodegib resistance.

Similar to advanced BCCs, vismodegib-resistant tumors also harbored more macrophages, less lymphocytes, and displayed higher Th1 and Th2 immune cytokine scores. CD8+ T lymphocytes were overrepresented in vismodegib-resistant BCCs while B and CD4+ T lymphocytes were underrepresented in these tumors. CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte infiltration has been noted in BCCs exposed to vismodegib (Otsuka et al. 2015), but it remains unclear at this point why vismodegib-resistant and vismodegib-sensitive BCCs have different T cell infiltration profiles.

Four main limitations arising from using RNA deconvolution and enrichment scores are important to highlight in this study. First, comparisons are affected by a lack of power due to small sample sizes. This was most pronounced for vismodegib-sensitive, vismodegib-treated tumors (n = 5); other groups have at least ten tumors. While there is no specific number as a minimal group size for these comparisons, other studies focusing on tumor microenvironment have used similarly sized groups for biologically meaningful comparisons. Song et al. compared the tumor microenvironment from 41 head and neck tumor samples and 11 control samples by CIBERSORT (Song et al. 2019), nearly identical to our advanced vs. non-advanced BCC comparison. Omland et al. successfully used 18 BCC samples to characterize important markers for cancer-associated fibroblasts and extra-cellular matrix remodeling, which were further validated experimentally (Omland et al. 2017b). A recent melanoma study compared the tumor environment by Gene Set Expression Analysis in six melanoma pre-treatment and six post-treatment samples (Bretz et al. 2019), which is similar in number to our vismodegib-sensitive BCC group. Second, given the in-silico nature, this study lacks histopathological validation by immunohistochemistry. Third, it is hard to deconvolute precisely closely-related cell types, or lower abundance cell types (Li et al. 2016). To decrease potential background noise from this, we have computed together in CIBERSORT the abundance of cell types that are closely related (for example, all CD4+ T lymphocytes). Also, for example, when evaluating Treg cells and γδ T lymphocytes, low abundance in most samples may render them harder to be accurately detected. Fourth, cancer cells may have transcriptional profiles that resemble that of a distinct, unrelated cell population and, thus, can be incorrectly classified (Aran et al. 2016). In our study, we found a higher mesenchymal stem cell score in advanced and treatment-resistant BCCs. We hypothesize that these are related to BCC cells undergoing identity/phenotype switch, as previously reported (Biehs et al. 2018). However, stromal reaction or a notable change in immune cell gene expression may represent alternative explanations for our findings.

Conclusions

We have found several key differences in immune cell composition, cytokine polarity and mesenchymal cell profiles that can help explain the wide spectrum of biological behaviors observed in BCCs depending on the clinical context, from most benign to locally advanced, metastatic or high-risk. A better understanding of the tumoral microenvironment and, specifically, immune cell infiltration patterns, may lead to enhanced therapeutic response by selecting treatments that act on certain subpopulations of immune cells (Binnewies et al. 2018). Targeted therapies for BCCs are currently geared towards advanced cases and are administered systemically. However, >99% of BCCs are considered “routine” (Goldenberg et al. 2016). Physical modalities such as surgery may lead to complications. Topical application of new targeted agents to the tumor itself with minimal side effects is preferable, as long as the efficacy is not compromised. To this end, understanding BCC’s microenvironment may enable more precise immunotherapy and may provide important clues about how to circumvent treatment resistance.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 1430 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Frederic de Sauvage (Genentech) and Dr. Sergey Nikolaev (University of Geneva) for generously sharing their data. This research was enabled in part by support provided by Calcul Québec (www.calculquebec.ca), Compute Ontario (www.computeontario.ca), WestGrid (www.westgrid.ca) and Compute Canada (www.computecanada.ca).

Authors’ contributions

PL designed the study. PL and PX performed computational experiments. PL and PX analyzed the data. SG, JG and AMV helped prepare figures and tables. DS and IVL supervised the study. All authors contributed to the writing the manuscript.

Funding information

This work was supported by the Canadian Dermatology Foundation research grants to Dr. Sasseville and Dr. Litvinov, and by the Fonds de la recherche du Québec – Santé to Dr. Sasseville (#22648) and to Dr. Litvinov (#34753 and #36769). Ms. Amelia Martinez Villarreal received a fellowship support from the CONACYT (Government of Mexico), while Mrs. Gantchev received a Ph.D. fellowship from Cole Foundation. Funding sources played no role in study design or in data collection, analysis or interpretation.

Data Availability

Previously published whole-genome RNA-Seq data originated from: Atwood et al. (GEO accession number GSE58377) (Atwood et al. 2015), Bonilla et al. (EGA accession number EGAS00001001540) (Bonilla et al. 2016), and Sharpe et al. (EGA accession number EGAS00001000845) (Sharpe et al. 2015).

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Philippe Lefrançois, Email: philippe.lefrancois2@mail.mcgill.ca.

Pingxing Xie, Email: pingxing.xie@mail.mcgill.ca.

Scott Gunn, Email: sgunn@qmed.ca.

Jennifer Gantchev, Email: jennifer.theoret@mail.mcgill.ca.

Amelia Martínez Villarreal, Email: amelia.martinezvillarreal@mail.mcgill.ca.

Denis Sasseville, Email: denis.sasseville@mcgill.ca.

Ivan V. Litvinov, Email: ivan.litvinov@mcgill.ca

References

- Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq--a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aran D, Lasry A, Zinger A, Biton M, Pikarsky E, Hellman A, Butte AJ, Ben-Neriah Y. Widespread parainflammation in human cancer. Genome Biol. 2016;17:145. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0995-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aran D, Hu Z, Butte AJ. xCell: digitally portraying the tissue cellular heterogeneity landscape. Genome Biol. 2017;18:220. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1349-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aran D, Camarda R, Odegaard J, Paik H, Oskotsky B, Krings G, Goga A, Sirota M, Butte AJ. Comprehensive analysis of normal adjacent to tumor transcriptomes. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1077. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01027-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood SX, Sarin KY, Whitson RJ, Li JR, Kim G, Rezaee M, Ally MS, Kim J, Yao C, Chang AL, et al. Smoothened variants explain the majority of drug resistance in basal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:342–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertheim U, Hofer PA, Engstrom-Laurent A, Hellstrom S. The stromal reaction in basal cell carcinomas. A prerequisite for tumour progression and treatment strategy. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57:429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biehs B, Dijkgraaf GJP, Piskol R, Alicke B, Boumahdi S, Peale F, Gould SE, de Sauvage FJ. A cell identity switch allows residual BCC to survive hedgehog pathway inhibition. Nature. 2018;562:429–433. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0596-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, Chan V, Fearon DF, Merad M, Coussens LM, Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Hedrick CC, Vonderheide RH, Pittet MJ, Jain RK, Zou W, Howcroft TK, Woodhouse EC, Weinberg RA, Krummel MF. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med. 2018;24:541–550. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0014-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla X, Parmentier L, King B, Bezrukov F, Kaya G, Zoete V, Seplyarskiy VB, Sharpe HJ, McKee T, Letourneau A, et al. Genomic analysis identifies new drivers and progression pathways in skin basal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2016;48:398–406. doi: 10.1038/ng.3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretz AC, Parnitzke U, Kronthaler K, Dreker T, Bartz R, Hermann F, Ammendola A, Wulff T, Hamm S. Domatinostat favors the immunotherapy response by modulating the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:294. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0745-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang AI, Schwertschkow AH, Nolta JA, Wu J. Involvement of mesenchymal stem cells in cancer progression and metastases. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2015;15:88–98. doi: 10.2174/1568009615666150126154151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNardo DG, Barreto JB, Andreu P, Vasquez L, Tawfik D, Kolhatkar N, Coussens LM. CD4(+) T cells regulate pulmonary metastasis of mammary carcinomas by enhancing protumor properties of macrophages. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erreni M, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumor-associated Macrophages (TAM) and inflammation in colorectal Cancer. Cancer Microenviron. 2011;4:141–154. doi: 10.1007/s12307-010-0052-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentles AJ, Newman AM, Liu CL, Bratman SV, Feng W, Kim D, Nair VS, Xu Y, Khuong A, Hoang CD, et al. The prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across human cancers. Nat Med. 2015;21:938–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givechian KB, Wnuk K, Garner C, Benz S, Garban H, Rabizadeh S, Niazi K, Soon-Shiong P. Identification of an immune gene expression signature associated with favorable clinical features in Treg-enriched patient tumor samples. NPJ Genom Med. 2018;3:14. doi: 10.1038/s41525-018-0054-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg G, Karagiannis T, Palmer JB, Lotya J, O'Neill C, Kisa R, Herrera V, Siegel DM. Incidence and prevalence of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and locally advanced BCC (LABCC) in a large commercially insured population in the United States: A retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:957–966.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaporis HG, Guttman-Yassky E, Lowes MA, Haider AS, Fuentes-Duculan J, Darabi K, Whynot-Ertelt J, Khatcherian A, Cardinale I, Novitskaya I, Krueger JG, Carucci JA. Human basal cell carcinoma is associated with Foxp3+ T cells in a Th2 dominant microenvironment. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2391–2398. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur P, Mulvaney M, Carlson JA. Basal cell carcinoma progression correlates with host immune response and stromal alterations: a histologic analysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:293–307. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200608000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefrancois P, Xie P, Wang L, Tetzlaff MT, Moreau L, Watters AK, Netchiporouk E, Provost N, Gilbert M, Ni X, et al. Gene expression profiling and immune cell-type deconvolution highlight robust disease progression and survival markers in multiple cohorts of CTCL patients. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1467856. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1467856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Severson E, Pignon JC, Zhao H, Li T, Novak J, Jiang P, Shen H, Aster JC, Rodig S, et al. Comprehensive analyses of tumor immunity: implications for cancer immunotherapy. Genome Biol. 2016;17:174. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1028-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A. B cells and macrophages in cancer: yin and yang. Nat Med. 2011;17:285–286. doi: 10.1038/nm0311-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migden MR, Guminski A, Gutzmer R, Dirix L, Lewis KD, Combemale P, Herd RM, Kudchadkar R, Trefzer U, Gogov S, Pallaud C, Yi T, Mone M, Kaatz M, Loquai C, Stratigos AJ, Schulze HJ, Plummer R, Chang AL, Cornélis F, Lear JT, Sellami D, Dummer R. Treatment with two different doses of sonidegib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma (BOLT): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:716–728. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DL, Weinstock MA. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States: incidence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:774–778. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81509-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montuenga LM, Pio R. Tumour-associated macrophages in nonsmall cell lung cancer: the role of interleukin-10. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:608–610. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00091707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M, Alizadeh AA. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 2015;12:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omland SH. Local immune response in cutaneous basal cell carcinoma. Dan Med J. 2017;64:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omland SH, Nielsen PS, Gjerdrum LM, Gniadecki R. Immunosuppressive environment in basal cell carcinoma: the role of regulatory T cells. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:917–921. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omland SH, Hamrouni A, Gniadecki R. High diversity of the T-cell receptor repertoire of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in basal cell carcinoma. Exp Dermatol. 2017;26:454–456. doi: 10.1111/exd.13240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omland SH, Wettergren EE, Mollerup S, Asplund M, Mourier T, Hansen AJ, Gniadecki R. Cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are activated in cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and in the peritumoural skin. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:675. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3663-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka A, Dreier J, Cheng PF, Nageli M, Lehmann H, Felderer L, Frew IJ, Matsushita S, Levesque MP, Dummer R. Hedgehog pathway inhibitors promote adaptive immune responses in basal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1289–1297. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, Hinckley MR, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, Coldiron BM. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283–287. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohr-Udilova N, Klinglmuller F, Schulte-Hermann R, Stift J, Herac M, Salzmann M, Finotello F, Timelthaler G, Oberhuber G, Pinter M, et al. Deviations of the immune cell landscape between healthy liver and hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2018;8:6220. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24437-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin AI, Chen EH, Ratner D. Basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2262–2269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra044151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Danes A, Larsimont JC, Liagre M, Munoz-Couselo E, Lapouge G, Brisebarre A, Dubois C, Suppa M, Sukumaran V, Del Marmol V, et al. A slow-cycling LGR5 tumour population mediates basal cell carcinoma relapse after therapy. Nature. 2018;562:434–438. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0603-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, Dirix L, Lewis KD, Hainsworth JD, Solomon JA, Yoo S, Arron ST, Friedlander PA, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2171–2179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe HJ, Pau G, Dijkgraaf GJ, Basset-Seguin N, Modrusan Z, Januario T, Tsui V, Durham AB, Dlugosz AA, Haverty PM, Bourgon R, Tang JY, Sarin KY, Dirix L, Fisher DC, Rudin CM, Sofen H, Migden MR, Yauch RL, de Sauvage FJ. Genomic analysis of smoothened inhibitor resistance in basal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:327–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen-Orr SS, Gaujoux R. Computational deconvolution: extracting cell type-specific information from heterogeneous samples. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:571–578. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Deng Z, Su J, Yuan D, Liu J, Zhu J. Patterns of immune infiltration in HNC and their clinical implications: a gene expression-based study. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1285. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xie P, Lefrancois P. Efficacy, safety, and comparison of sonic hedgehog inhibitors in basal cell carcinomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:1089–1100 e1017. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 1430 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Previously published whole-genome RNA-Seq data originated from: Atwood et al. (GEO accession number GSE58377) (Atwood et al. 2015), Bonilla et al. (EGA accession number EGAS00001001540) (Bonilla et al. 2016), and Sharpe et al. (EGA accession number EGAS00001000845) (Sharpe et al. 2015).