Abstract

In rats, overnight fasting reduces the ability of systemic cholecystokinin-8 (CCK) to suppress food intake and to activate cFos in the caudal nucleus of the solitary tract (cNTS), specifically within glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and noradrenergic (NA) neurons of the A2 cell group. Systemic CCK increases vagal sensory signaling to the cNTS, an effect that is amplified by leptin and reduced by ghrelin. Since fasting reduces plasma leptin and increases plasma ghrelin levels, we hypothesized that peripheral leptin administration and/or antagonism of ghrelin receptors in fasted rats would rescue the ability of CCK to activate GLP-1 neurons and a caudal subset of A2 neurons that coexpress prolactin-releasing peptide (PrRP). To test this, cFos expression was examined in ad libitum-fed and overnight food-deprived (DEP) rats after intraperitoneal CCK, after coadministration of leptin and CCK, or after intraperitoneal injection of a ghrelin receptor antagonist (GRA) before CCK. In fed rats, CCK activated cFos in ~60% of GLP-1 and PrRP neurons. Few or no GLP-1 or PrRP neurons expressed cFos in DEP rats treated with CCK alone, CCK combined with leptin, or GRA alone. However, GRA pretreatment increased the ability of CCK to activate GLP-1 and PrRP neurons and also enhanced the hypophagic effect of CCK in DEP rats. Considered together, these new findings suggest that reduced behavioral sensitivity to CCK in fasted rats is at least partially due to ghrelin-mediated suppression of hindbrain GLP-1 and PrRP neural responsiveness to CCK.

Keywords: cholecystokinin-8, cFos, fasting, hypophagia, satiety

INTRODUCTION

In rats with ad libitum food access, systemically administered cholecystokinin-8 (CCK) increases the firing rate of gastrointestinal vagal sensory neurons that innervate the caudal (visceral) nucleus of the solitary tract (cNTS), promoting activation of cFos expression in noradrenergic (NA) neurons of the A2 cell group and in glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1)-positive cNTS neurons (3, 52, 58–60, 62, 65). A caudal subset of A2 NA neurons that coexpress prolactin-releasing peptide (PrRP) (48) has been especially implicated in the hypophagic effect of systemic CCK (40, 42, 71). In addition to eliciting hypophagia (31, 39), central NA/PrRP and GLP-1 signaling pathways contribute to other physiological and behavioral components of energy balance and metabolism, including stress responses (16, 35, 43, 44, 50).

Interestingly, overnight food deprivation in rats significantly attenuates CCK-induced activation of cFos in A2 NA neurons and virtually eliminates activation of GLP-1 neurons (45). The hypophagic efficacy of systemic CCK also is reduced in food-deprived (DEP) rats, such that higher doses of CCK are necessary to inhibit food intake in 48-h- versus 12-h- or 3-h-fasted rats (11, 51). The ability of negative energy balance to attenuate stimulus-induced activation of GLP-1 and A2 NA neurons (the latter including the PrRP-positive subpopulation) in DEP rats may contribute to the known effect of caloric deficit to reduce satiety signaling and also to reduce hormonal and behavioral responses to stressful stimuli (1, 28, 29, 34, 41, 47).

Nocturnal laboratory rats consume most of their daily calories during the dark cycle of the photoperiod, even when food is continuously available. In adult rats, one night of food deprivation (i.e., overnight fasting) promotes body weight loss of 8–10% and generates a variety of physiological and metabolic effects (19) that might directly or indirectly reduce the responsiveness of GLP-1 neurons and the PrRP-positive subset of A2 neurons to experimental treatments or natural stimuli that normally activate these cNTS neurons. Reduced neural and behavioral responsiveness to exogenous CCK in fasted rats could result from loss of an excitatory signal that is present in fed rats, and/or from enhancement of an inhibitory signal that is generated by food deprivation. For example, plasma leptin levels fall in rats during overnight fasting (19, 57), while plasma ghrelin levels rise (6, 18, 69). Considering this, we speculated that a fasting-induced reduction in leptin signaling or an increase in ghrelin signaling might contribute to the documented suppression of hindbrain neural and behavioral responses to CCK in fasted rats.

Leptin, the peptide product of the obese (Ob) gene, is released from adipose tissue and the gastric epithelium to signal long- and short-term caloric surfeit, respectively (5, 79). Leptin binds to receptors expressed on the vagus nerve (12, 13) to depolarize vagal sensory neurons that synapse within the cNTS (56). When vagal sensory neurons from the nodose ganglion are studied in vitro, the majority of cells depolarized by leptin also are depolarized by CCK (55), and coadministration of leptin enhances CCK-induced elevations in cytosolic calcium (54). After transport across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (8), leptin also directly increases the excitability of cNTS neurons that express leptin receptors, including cNTS A2 neurons in rats (26, 30, 33, 46). Since leptin increases the ability of CCK to activate vagal afferents and cNTS neurons (27, 73, 75) and to suppress caloric intake (10, 27, 49), and considering that plasma leptin levels fall in rats during overnight fasting (19, 57), reduced leptin signaling is a strong candidate factor underlying fasting-induced decreases in GLP-1 and PrRP neuronal activation and behavioral responses to exogenous CCK.

The second candidate mediator of fasting-induced suppression of CCK responsiveness is ghrelin, a potent orexigenic hormone produced by cells of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract (20, 36, 68). Ghrelin secretion increases during fasting (6, 18, 69), and ghrelin receptors are expressed by CCK-sensitive vagal afferents. Ghrelin acts at these receptors to decrease the firing rate of vagal afferents (21, 22), and ghrelin pretreatment blocks the ability of CCK to increase vagal afferent spike frequency (22). Thus, ghrelin reduces glutamatergic vagal sensory signaling to postsynaptic cNTS neurons (3), including signaling evoked by CCK. Similarly to leptin, ghrelin is transported across the BBB (9), and this transport is facilitated during fasting (7). Within the cNTS, ghrelin acts directly on the synaptic terminals of vagal afferents to suppress glutamate release onto NA neurons of the A2 cell group, leading to reductions in postsynaptic neural firing (17). Interestingly, the ability of ghrelin to suppress glutamatergic vagal afferent signaling is enhanced in rats after an overnight fast (17), suggesting that increased ghrelin signaling in fasted rats suppresses CCK-induced activation of cNTS neurons.

Considering the evidence summarized above, the present study was designed to investigate whether reduced effectiveness of systemic CCK to activate cFos expression by GLP-1 and PrRP neurons and to suppress food intake in fasted rats can be reversed either by increasing circulating levels of leptin, or by antagonizing ghrelin receptors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

To examine cFos activation (experiments 1 and 2), adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, IN; 225–275 g body wt) were housed singly in hanging stainless steel wire mesh cages in a temperature-controlled vivarium (20–22°C) on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle (lights on at 0700). Rats had ad libitum access to pelleted chow (Purina 5001) and water, except as noted.

To examine food intake (experiment 3), adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, IN; 290–400 g body wt) were individually housed in a temperature-controlled vivarium (20–22°C) on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle (lights on at 0600) equipped with a computerized BioDAQ feeding monitoring system (Research Diets). Rats had ad libitum access to pelleted chow (Purina 5001) and water, except as noted. The BioDAQ system uses standard tub cages with wood chip bedding and wire cage tops; each cage was equipped with a water bottle on top of the cage and a food hopper on one end of the cage connected to a digital scale to record the time and amount of food removed from the hopper. Unconsumed chow crumb debris (spillage) collects into a small pan below the hopper and is thus detected on the same digital scale.

In each experiment, rats were deprived of food (but not water) for 16–18 h overnight before drug or vehicle treatments. Rats were weighed the afternoon before fasting to determine drug dosages. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Pittsburgh (cFos experiments) and Florida State University (food intake experiment).

Experiment 1: CCK-induced cFos after coadministration of leptin.

On the day of the experiment, fasted rats (n = 8) were removed from their home cages between 0830 and 1030 and injected intraperitoneally with 1.0 mL of sterile 0.15 M NaCl vehicle containing leptin alone (400 or 800 μg/kg body wt; Sigma-Aldrich, L5037; n = 4), or leptin plus sulfated CCK (3 μg/kg body wt; Bachem, H-2080; n = 4). The rationale for simultaneous administration of leptin and CCK was based on published reports (2, 10, 73). CCK and/or leptin were dissolved in vehicle just before injection, and rats were returned to their home cages immediately after injection. The selected dose of CCK (3 μg/kg body wt) was based on our previous report in which the same dose elicited robust cFos activation in GLP-1 and A2 neurons in fed rats but not in rats fasted overnight (45). The 400 and 800 μg/kg body wt doses of leptin were selected because they elicit similarly robust increases in phosphorylated (p-)STAT3 immunolabeling within the cNTS and other brain regions in fasted rats (46). There was no difference in the ability of these two leptin doses to alter hindbrain neural activation after CCK treatment in the present study; thus, data from rats receiving either leptin dose were combined into a single treatment group for statistical analysis.

Experiment 2: CCK-induced cFos after pretreatment with ghrelin receptor antagonist.

On the day of the experiment, fasted rats (n = 20) were removed from their home cages between 0830 and 1030. Rats were assigned to one of four intraperitoneal injection/treatment groups (n = 4–8 rats/group) as follows: 1) vehicle (0.15 M NaCl, 1.0 mL), 2) vehicle containing ghrelin receptor antagonist (GRA; [d-Lys3]GHRP-6, 3.3 mg/kg body wt; Sigma-Aldrich, G4535), 3) vehicle followed 30 min later by CCK (3 μg/kg body wt), or 4) GRA followed 30 min later by CCK. Pretreatment with GRA (or saline, to control for dual injections) was performed to antagonize ghrelin receptors before CCK treatment. GRA doses of 0.6–6.0 mg/kg body wt suppress fasting-induced food intake in mice after intraperitoneal administration (4); our selected GRA dose in rats was slightly above the midpoint of this dose range. The 30-min delay between GRA and CCK treatment was chosen based on evidence that intraperitoneal GRA reduces food intake within this timeframe in food-deprived mice (4).

cFos experiments 1 and 2: perfusion and tissue processing.

Rats were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (39 mg/1.0 mL ip, Fatal Plus Solution, Butler Schein) 90 min after the second (or only) intraperitoneal injection and then perfused transcardially with a brief saline rinse followed by fixative (100 mL of 2% paraformaldehyde and 1.5% acrolein in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, followed by 100 mL of 2% paraformaldehyde alone). Brains were postfixed in situ overnight at 4°C and then removed from the skull and cryoprotected for 24–48 h in 20% sucrose. Brains were blocked and sectioned coronally (35 μm) using a Leica freezing-stage sliding microtome. Tissue sections were collected in six serial sets and stored at −20°C in cryopreservant solution (74) before immunocytochemical processing. For comparative purposes and to obtain new data for CCK-induced cFos activation in PrRP neurons, cryopreserved sets of tissue generated in a previous study (45) were added to the current analyses. These additional tissue sets came from adult male Sprague-Dawley rats that were either fed (n = 4) or food deprived overnight (DEP; n = 4) before intraperitoneal injection of CCK (3 μg/kg body wt), followed by perfusion fixation 90 min later with tissue postfixation, cryoprotection, and sectioning, as described above. These additional sets of tissue were processed immunocytochemically together with the newly generated tissue sets, as described below.

Primary and secondary antisera were diluted in 0.1 M phosphate buffer containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 1% normal donkey serum. Two sets of tissue sections from each rat were incubated in a rabbit polyclonal antiserum against cFos (1:20,000; EMD Chemicals, Millipore no. PC38, AB_2106755; antibody since discontinued), followed by biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch). Sections were then treated with Elite Vectastain ABC reagents (Vector) and reacted with diaminobenzidine (DAB) intensified with nickel sulfate to produce a blue-black nuclear cFos reaction product. This cFos antibody recognizes the ∼55-kDa cFos protein but not the ∼39-kDa Jun protein, according to the vendor. Immunolabeling using this antibody is colocalized with c‐fos mRNA in rat brain under a variety of conditions, and preabsorbing the antibody with the synthetic peptide immunogen eliminates immunolabeling (63).

To visualize cFos within hindbrain GLP-1 neurons, one set of cFos-labeled tissue sections was subsequently incubated in a rabbit polyclonal antiserum against GLP-1 (1:10,000; Bachem, T-4363, AB_518978), followed by incubation in biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch) and Elite Vectastain ABC reagents (Vector) and then reacted with plain DAB to produce a brown cytoplasmic reaction product. The GLP-1 antibody was generated against a synthetic peptide corresponding to amino acids 7–37 of the human GLP‐1 sequence. Specificity of this antiserum as applied to rat and human brain tissue has been documented (81), including an absence of immunolabeling after preabsorbing of the primary antiserum overnight at 4°C with a 10‐fold higher concentration of synthetic GLP‐1(7–37) acetate salt (H‐9560; Bachem, Torrance, CA) before tissue incubation.

To visualize PrRP neurons in the cNTS, the second set of cFos-labeled tissue sections was incubated in rabbit anti-PrRP (1:1,000; Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, H-008-52). After rinsing, sections were incubated in Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:300, Jackson ImmunoResearch) to produce a red fluorescent cytoplasmic signal. The PrRP antibody was raised against the synthetic 31-amino acid sequence of rat PrRP peptide. Antibody specificity has been documented by the manufacturer and also within our laboratory, based on positive and specific immunolabeling of a subset of dopamine β-hydroxylase (DbH)‐positive NA neurons in the rat caudal brain stem (43, 47) and fully consistent with the reported distribution of PrRP mRNA expression and immunolabeling in mice and rats (26, 39).

Imaging and quantification of cFos expression by GLP-1 neurons.

GLP-1 neurons were visualized using a light microscope and ×20/40 objectives to document the number of double-labeled neurons immunopositive for both cFos and GLP-1. Single- and double-labeled GLP-1 neurons were quantified bilaterally within the cNTS and adjacent reticular formation, with counts made through the entire rostrocaudal extent of the GLP-1 cell group (i.e., from the cervical spinal cord through the NTS just rostral to the area postrema; ~15.46 mm to 13.15 mm caudal to bregma). Criteria for counting a neuron as GLP-1 positive included brown cytoplasmic labeling and a visible nucleus. Criteria for counting a neuron as double labeled included brown GLP-1 cytoplasmic labeling and a nucleus that contained visible blue-black cFos immunolabeling, regardless of intensity. In each analyzed case, cFos-positive (i.e., activated) GLP-1 neurons were represented as the proportion of all GLP-1 neurons counted in that case.

Imaging and quantification of cFos expression by PrRP neurons.

The PrRP-positive subset of cNTS A2 neurons was visualized using a ×20 objective on an Olympus microscope equipped for bright-field and epifluorescence and photographed using a digital camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). Neurons were counted in photographic images by using Adobe Photoshop CS4 image software. Criteria for counting a neuron as PrRP positive included clear cytoplasmic labeling and a visible nucleus. Neurons were considered cFos positive if their nucleus contained blue-black cFos immunoperoxidase labeling, regardless of intensity. Single- and double-labeled neurons were counted bilaterally through the rostrocaudal extent of the PrRP cell group (i.e., from the cervical spinal cord through the NTS at the level just rostral to the area postrema; ~15.46 mm to 13.15 mm caudal to bregma). In each analyzed case, cFos-activated PrRP neurons are represented as the proportion of all PrRP neurons counted. Images shown in Figures 1B and 2B were generated by inverting the brightfield cFos images and converting white cFos labeling to green.

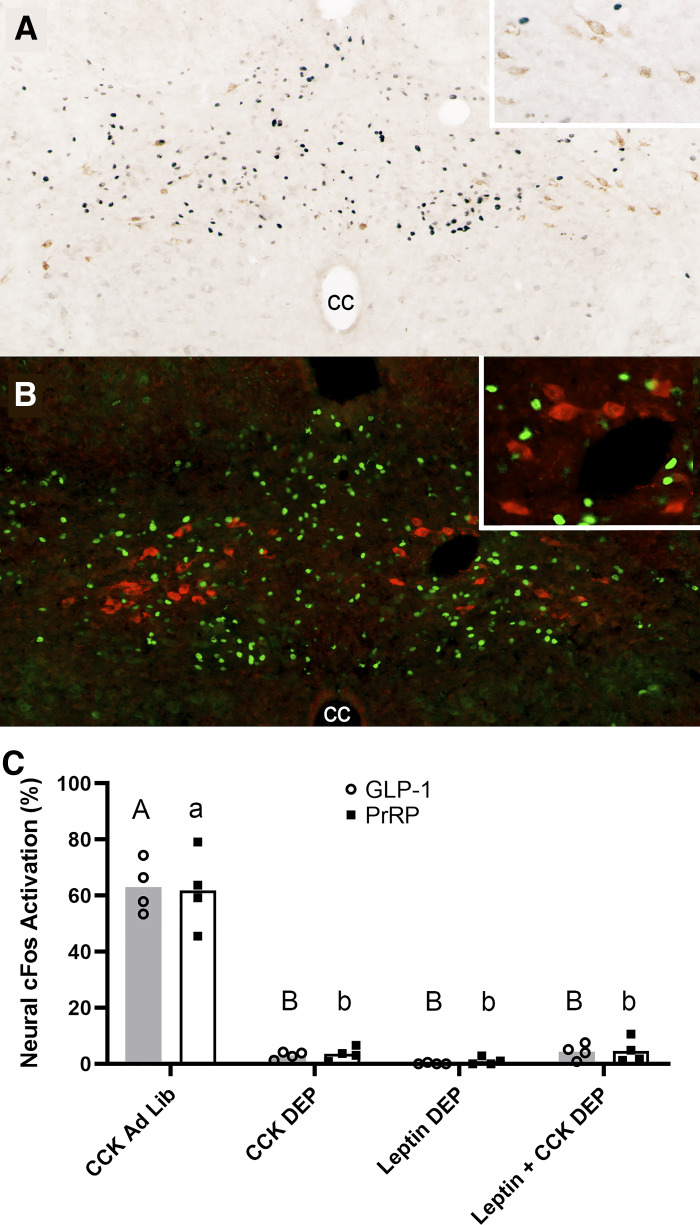

Fig. 1.

Leptin is insufficient to rescue CCK-induced activation of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) or prolactin-releasing peptide (PrRP) neurons in overnight food-deprived (DEP) rats. A: color image depicting neuronal cFos expression (black nuclear label) and GLP-1 immunolabeling (brown cytoplasmic label) in the caudal nucleus of the solitary tract (cNTS) of a DEP rat that received intraperitoneal coinjection of CCK (3 μg/kg body wt) and leptin (800 μg/kg body wt). Despite robust cNTS cFos activation, very few double-labeled neurons (i.e., positive for both cFos and GLP-1) are present. Inset: higher-magnification view of several GLP-1 neurons, none of which express cFos. cc, central canal. B: color image depicting neuronal cFos expression (green nuclear label) and PrRP neurons (red cytoplasmic label) in the cNTS of a DEP rat that received intraperitoneal coinjection of CCK (3 μg/kg body wt) and leptin (800 μg/kg body wt). Despite robust cNTS cFos activation, very few double-labeled neurons (i.e., immunopositive for both cFos and PrRP) are present. Inset: higher-magnification view of several PrRP neurons, none of which express cFos. C: summary data reporting the proportion of cFos-positive hindbrain GLP-1 neurons (shaded bars; open circles are individual data points) or PrRP neurons (open bars; solid squares are individual data points) in ad libitum-fed (Ad Lib) vs. fasted (DEP) rats (n = 4/treatment group). Within the same neuronal population (i.e., GLP-1 or PrRP), bar values with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05).

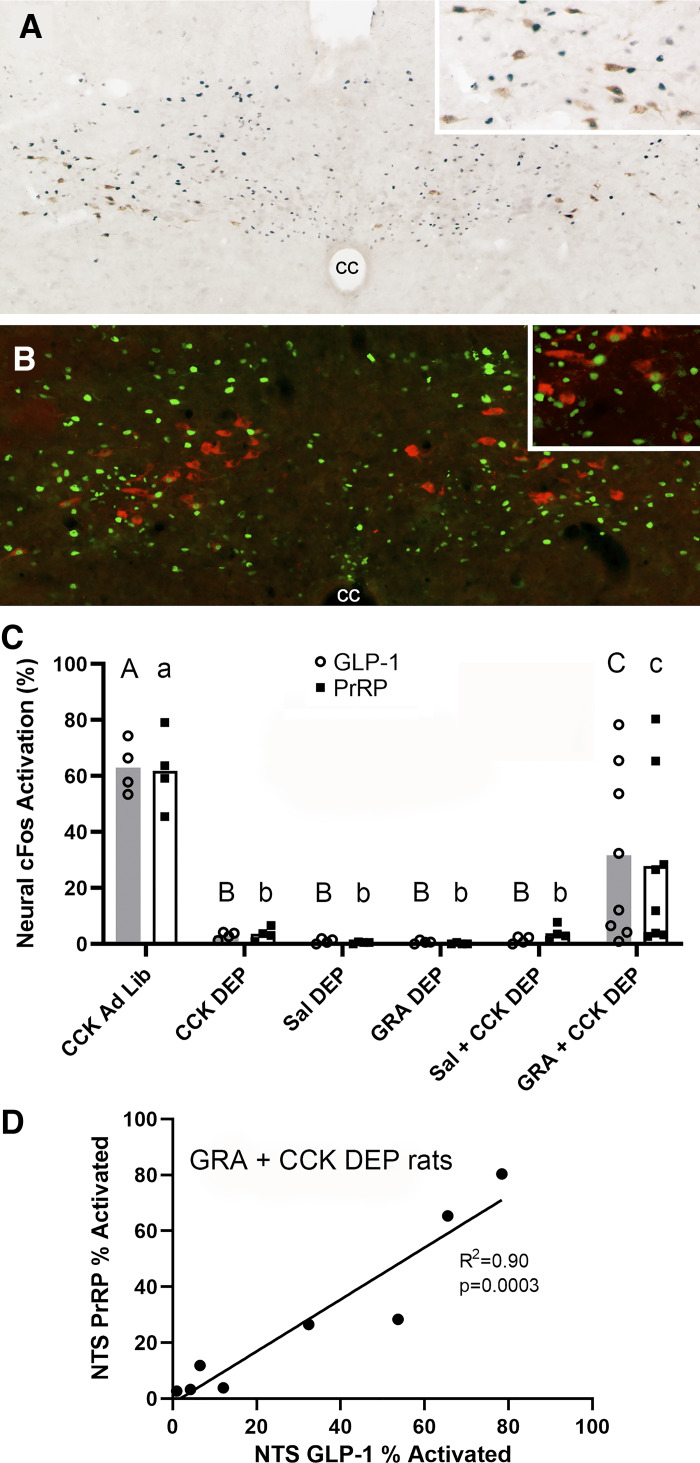

Fig. 2.

Ghrelin receptor antagonism enhances CCK-induced activation of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and prolactin-releasing peptide (PrRP) neurons in overnight food-deprived (DEP) rats. A: color image depicting neuronal cFos expression (black nuclear label) within GLP-1 neurons (brown cytoplasmic label) in the caudal nucleus of the solitary tract (cNTS) of a DEP rat that received intraperitoneal pretreatment with ghrelin receptor antagonist (GRA; 3.3 mg/kg body wt) before intraperitoneal CCK (3 μg/kg body wt). Inset: higher-magnification view of several GLP-1 neurons, many of which express cFos. cc, central canal. B: color image depicting neuronal cFos expression (green nuclear label) within PrRP neurons (red cytoplasmic label) in the cNTS of a DEP rat that received intraperitoneal pretreatment with GRA (3.3 mg/kg body wt) before intraperitoneal CCK (3 μg/kg body wt). Inset: higher-magnification view of several PrRP neurons, some of which express cFos. C: summary data illustrating the proportion of cFos-positive hindbrain GLP-1 neurons (shaded bars; open circles are individual data points) or PrRP neurons (open bars; solid squares are individual data points) in ad libitum-fed (Ad Lib) vs. fasted (DEP) rats (n = 4/group, except n = 8 for GRA + CCK). Within the same neuronal population (i.e., GLP-1 or PrRP), bar values with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05). D: proportions of GLP-1- and PrRP-positive neurons activated to express cFos are highly correlated in individual DEP rats within the GRA + CCK treatment group (n = 8).

Statistical analysis of cFos data (experiments 1 and 2).

For each experiment, separate one-way ANOVAs were used to determine the effect of experimental treatment condition on activation of cFos in hindbrain GLP-1 and PrRP neurons in DEP rats. When F values indicated a significant main effect of treatment, ANOVA was followed by Fisher’s least significant difference post hoc tests. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Experiment 3: food intake in fasted rats treated with GRA before CCK.

Based on cFos data collected in experiments 1 and 2 (see results), we sought to determine whether GRA pretreatment increases the ability of CCK to suppress food intake in fasted rats. For this purpose, rats (n = 24) were acclimated for 3 days to individual housing in a BioDAQ automated food measurement system (Research Diets). To assess baseline fasting-induced food intake (i.e., after no intraperitoneal injections), BioDAQ-acclimated rats were overnight food deprived (18–19 h) with water freely available; chow was returned at 1000 the following morning, with intake measured for 1 h. Rats were then returned to ad libitum feeding conditions for 2 full days.

Before the experimental day, rats were again fasted overnight (18–19 h). At ~0930, fasted rats received an intraperitoneal injection of vehicle (0.15 M NaCl, 1.0 mL; n = 12) or vehicle containing GRA (3.3 mg/kg body wt; n = 12). Thirty minutes later, subgroups of the same rats (n = 6 per subgroup) received a second intraperitoneal injection of vehicle (1.0 mL), or vehicle containing CCK (1.0 μg/kg body wt). Food was returned immediately after the second intraperitoneal injection, with BioDAQ intake data collected for 1 h. CCK synergizes with feeding-induced gastric distension to activate vagal afferents and induce satiety, and we hypothesized that GRA pretreatment in fasted rats would enhance the ability of CCK to induce satiety and suppress food intake. Thus, instead of the higher CCK dose (3 μg/kg body wt) used to examine cFos activation in rats that were not allowed to feed (experiments 1 and 2), a lower dose of CCK (1 μg/kg body wt) was used in this behavioral experiment to facilitate detection of any GRA-mediated effect to amplify the hypophagic effect of CCK.

Statistical analysis of feeding data (experiment 3).

One-hour cumulative food intake data were divided into six 10-min bins and then analyzed using three-way repeated-measures ANOVA (with time as the repeated measure) to detect significant between-group interactions and effects of the first intraperitoneal injection (vehicle vs. GRA) and the second intraperitoneal injection (vehicle vs. CCK) on fasting-induced intake over time. In addition, fasting-induced food intake by each rat after its assigned intraperitoneal treatment regimen was compared with its own fasting-induced intake under baseline conditions (i.e., no injections). For each treatment group, paired t tests were used to detect within-subjects differences (baseline vs. intraperitoneal treatment) in cumulative food intake at 30 and 60 min. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: leptin coadministration does not enhance CCK-induced cFos activation in fasted rats.

Approximately 60% of GLP-1 and PrRP neurons were immunopositive for cFos in fed rats after CCK treatment (3 μg/kg), whereas significantly smaller proportions of each neural population (i.e., 3–5%) were cFos positive in DEP rats after CCK treatment (Fig. 1; see Table 1 for group SE values). The GLP-1 cFos data replicate those of our previous report (45), whereas the PrRP data are new; our earlier study reported CCK-induced activation of DbH-positive NA neurons within the A2 cell group in fed versus DEP rats but did not specifically examine the PrRP-positive subset of these neurons (45).

Table 1.

Experiment 1: CCK-induced cFos with leptin coadministration

| Intraperitoneal Treatment | Status | %GLP-1 Neurons Expressing cFos | %PrRP Neurons Expressing cFos |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCK | Fed | 63.03 ± 4.65a | 61.90 ± 6.94a |

| CCK | DEP | 3.02 ± 0.66b | 3.59 ± 1.16b |

| Leptin | DEP | 0.13 ± 0.13b | 0.99 ± 0.68b |

| Leptin + CCK | DEP | 4.35 ± 1.39b | 4.65 ± 2.14b |

Values are means ± SE. GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; PrRP, prolactin-releasing peptide; DEP, overnight food deprived.

Within the same column (i.e., same neural population) values with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05).

In DEP rats, coadministration of leptin with CCK did not increase the proportions of either GLP-1 or PrRP neurons that expressed cFos (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Separate ANOVAs confirmed a significant effect of experimental treatment on the proportion of GLP-1 and PrRP neurons that were activated to express cFos [GLP-1: F(3,12) = 153.173, P < 0.001; PrRP: F(3,12) = 63.683, P < 0.001]. Post hoc analyses for each ANOVA indicated that fed rats treated with CCK displayed significantly higher proportions of GLP-1 and PrRP neurons expressing cFos compared with all the other treatment groups (Table 1). There were no other differences in GLP-1 or PrRP neural activation between treatment groups (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Experiment 2: GRA pretreatment enhances CCK-induced cFos activation in fasted rats.

Cell count data from fed and DEP rats treated only with CCK (shown in Fig. 1C) are replotted in Fig. 2C to facilitate visual comparison of the two data sets. In contrast to leptin’s lack of effect on cFos activation (Fig. 1), GRA pretreatment in DEP rats partially restored the ability of CCK to activate cFos expression in both GLP-1 and PrRP neurons (Fig. 2; see Table 2 for group SE values). ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of treatment on the proportion of GLP-1 and PrRP neurons that also were cFos positive [GLP-1: F(5,22) = 9.025, P < 0.001; PrRP: F(5,22) = 8.092, P < 0.001]. Post hoc analyses indicated that fed rats treated with CCK displayed a significantly higher proportion of GLP-1 and PrRP neural activation compared with all other treatment groups (Table 2). Negligible GLP-1 and PrRP neural activation was observed in DEP rats treated with CCK alone, saline vehicle alone, GRA alone, or saline followed by CCK (Fig. 2). Conversely, pretreatment of DEP rats with GRA significantly increased CCK-induced activation of GLP-1 and PrRP neurons (Fig. 2 and Table 2). The ability of GRA pretreatment to enhance CCK-induced cFos activation in DEP rats was variable, such that cFos activation was restored to “fed” levels in some rats, whereas other rats displayed little or no effect of GRA pretreatment (Fig. 2, individual data points; see Table 2 for group SE values). Within this GRA + CCK treatment group, the proportions of GLP-1 and PrRP neurons expressing cFos were highly and significantly correlated within subjects (R = 0.90; Fig. 2D), evidence that both neural populations in each rat responded similarly to the GRA + CCK treatment.

Table 2.

Experiment 2: CCK-induced cFos after GRA pretreatment

| Intraperitoneal Treatment | Status | %GLP-1 Neurons Expressing cFos | %PrRP Neurons Expressing cFos |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCK | Fed | 63.03 ± 4.65a | 61.90 ± 6.94a |

| CCK | DEP | 3.02 ± 0.66b | 3.59 ± 1.16b |

| Saline | DEP | 1.02 ± 0.44b | 0.49 ± 0.17b |

| GRA | DEP | 0.69 ± 0.30b | 0.13 ± 0.13b |

| Saline + CCK | DEP | 1.38 ± 0.62b | 3.87 ± 01.38b |

| GRA + CCK | DEP | 31.73 ± 10.97c | 27.28 ± 10.55c |

Values are means ± SE. GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; PrRP, prolactin-releasing peptide; DEP, overnight food deprived; GRA, ghrelin receptor antagonist.

Within the same column (i.e., same neural population) values with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Experiment 3: GRA pretreatment enhances CCK-induced hypophagia in fasted rats.

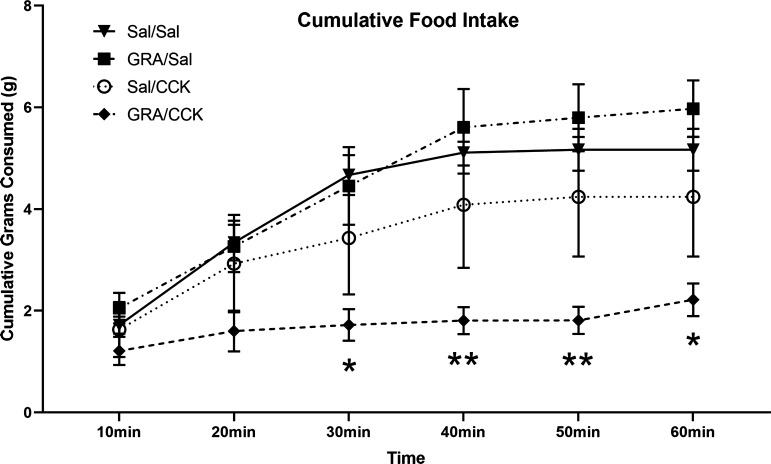

Figure 3 shows cumulative fasting-induced food intake by rats within each of the four experimental subgroups (n = 6/group). Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no main effect of the first intraperitoneal treatment (saline vs. GRA) on food intake [F(1,20) = 1.26, P > 0.05]. However, there was a main effect of the second intraperitoneal treatment [saline vs. CCK: F(1,20) = 8.55, P = 0.0084] on food intake and a main effect of time [F(2.37, 47.33) = 64.32, P < 0.0001]. There also was a significant two-way interaction between second intraperitoneal treatment (saline vs. CCK) and time [F(5,100) = 9.819, P < 0.0001] and a significant three-way interaction between first intraperitoneal treatment (saline vs. GRA), second intraperitoneal treatment (saline vs. CCK), and time [F(5,100) = 3.36, P = 0.0075]. As shown in Fig. 3, fasted rats that were pretreated with vehicle before CCK (Sal/CCK) appeared to consume less chow compared with fasted control rats treated only with vehicle (Sal/Sal) and also compared with fasted rats treated with GRA followed by vehicle (GRA/Sal); however, post hoc tests indicated that the apparent differences in food intake among these three groups were not significant at any time point. Conversely, compared with food intake by fasted control (Sal/Sal) rats, cumulative fasting-induced food intake was significantly suppressed in rats that were pretreated with GRA before CCK (GRA/CCK) at 30 min and later (30 min, P = 0.013; 40 min, P = 0.007; 50 min, P = 0.006; 60 min, P = 0.018; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

One-hour cumulative food intake (means ± SE) in overnight food-deprived (DEP) rats. DEP rats (n = 6/group) received intraperitoneal injection of ghrelin receptor antagonist (GRA; 3.3 mg/kg body wt) or saline vehicle (Sal), followed 30 min later by intraperitoneal injection of Sal or CCK (1 μg/kg body wt) just before food access. Compared with food intake by Sal/Sal control rats, feeding was suppressed only in rats that received GRA before CCK (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, GRA/Sal vs. Sal/Sal). Other between-group differences in food intake at each time point were not statistically significant.

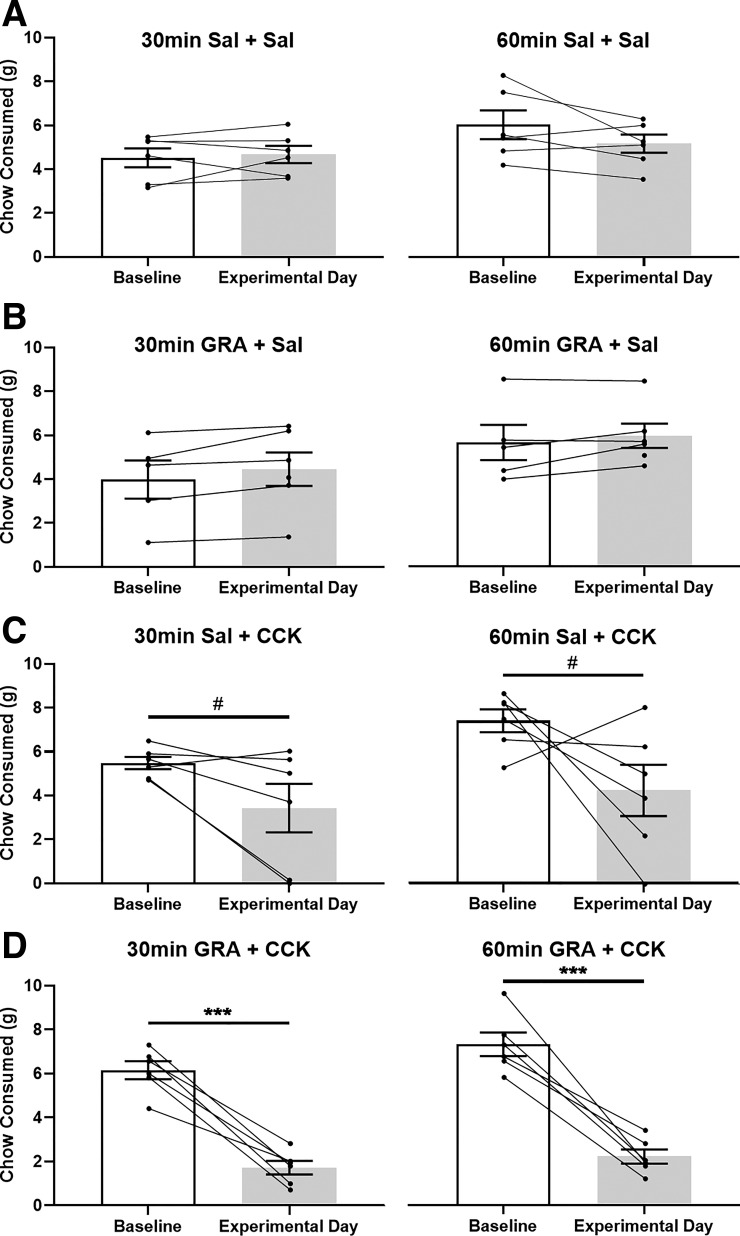

In each treatment group, fasting-induced chow intake also was evaluated within subjects by comparing 30- and 60-min cumulative intake after the experimental intraperitoneal treatment regimen to intake by the same rat under the noninjected baseline condition (Fig. 4). Paired t tests revealed no significant effect of intraperitoneal treatment on fasting-induced food intake in control rats that received two vehicle injections (Sal/Sal, P > 0.05 at each time point) or in rats that received GRA followed by vehicle (GRA/Sal, P > 0.05 at each time point). Rats that were treated with vehicle followed by CCK (Sal/CCK) displayed a strong trend toward suppression of fasting-induced intake, but this effect did not reach statistical significance at either time point (P = 0.075 at 30 min, P = 0.109 at 60 min; Fig. 4). Conversely, fasting-induced chow intake was significantly suppressed by ~70% in rats treated with GRA followed by CCK (GRA/CCK: P = 0.0004 at 30 min, P = 0.0005 at 60 min; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Within-subjects comparison of fasting-induced food intake by overnight food-deprived (DEP) rats within each treatment group. Open bars depict cumulative 30-min (left) and 60-min (right) chow intake (means ± SE) by DEP rats under baseline (i.e., noninjected) conditions. Shaded bars depict fasting-induced chow intake by the same rats after intraperitoneal injection of saline (Sal) or ghrelin receptor antagonist (GRA; 3.3 mg/kg body wt), followed 30 min later by intraperitoneal injection of saline or CCK (1 μg/kg body wt) just before food access (n = 6/group). Within-subject data points are connected by lines. Compared with baseline intake, 30- and 60-min food intakes were suppressed only in GRA + CCK-treated rats (D: ***P < 0.001). Conversely, rats treated with Sal + CCK displayed only a nonsignificant trend (C: #P = 0.075 at 30 min, #P = 0.109 at 60 min) toward suppression of fasting-induced food intake.

DISCUSSION

In ad libitum-fed rats, ~20–25% of GLP-1- and PrRP-positive cNTS neurons express cFos under baseline (nontreated control) conditions or after intraperitoneal saline (25, 45, 47). We (45) discovered that overnight fasting essentially eliminates this “baseline” level of neural cFos expression and markedly reduces the ability of CCK to activate GLP-1 neurons and NA neurons of the A2 cell group. PrRP is coexpressed by the most caudal subset of A2 neurons, and this specific subpopulation is activated to express cFos in fed rats treated with high [50 μg/kg body wt (42)] or low [1 μg/kg body wt (71)] systemic doses of CCK. Our new data confirm those reports and further indicate that overnight fasting blocks the ability of CCK (3 μg/kg body wt) to activate PrRP neurons, similar to the effect of fasting to “silence” GLP-1 neuronal activation. We further demonstrate that GRA pretreatment partially reverses the effect of fasting to suppress GLP-1 and PrRP neural responsiveness to CCK and that GRA pretreatment in fasted rats increases behavioral sensitivity to the hypophagic effect of CCK.

Fasting blocks CCK-induced activation of GLP-1 and PrRP neurons.

In fed rats, intraperitoneal CCK (3 μg/kg body wt) activated cFos expression in ~60% of hindbrain GLP-1 and PrRP neurons. The GLP-1 data are an internal replication of our previous report (45), whereas the novel PrRP data extend previous reports examining CCK-induced cFos activation in fed rats (40, 45, 60, 71). Lawrence et al. (40) reported that a dose of CCK higher than that used in the present study (i.e., 50 μg/kg body wt) activates cFos expression in ~85% of PrRP-positive cNTS neurons, whereas we reported that a lower dose of CCK (i.e., 1 μg/kg body wt) activates ~40% of PrRP neurons (71). Considered together with results from the present study, a dose-response relationship for CCK-induced recruitment of PrRP neurons in fed rats is apparent. Conversely, neither PrRP neurons nor GLP-1 neurons are activated to express cFos in fasted rats after CCK treatment. The effect of overnight fasting on GLP-1 neural activation was reported previously (45), whereas the PrRP data are new. In our earlier report, overnight food deprivation significantly attenuated the ability of CCK (3 μg/kg body wt) to activate DbH-positive NA neurons within the A2/C2 cell groups of the cNTS, but only by ~50%. The ability of CCK to suppress food intake appears to depend on the integrity of NA neurons within the A2 cell group (59), including the PrRP-positive subpopulation of these neurons (24, 66, 71). In this regard, our new findings indicate that overnight fasting almost completely blocks CCK-induced activation of cNTS PrRP neurons. We did not count the total number of cFos-positive neurons within the cNTS in the present study, since our focus was specifically the PrRP and GLP-1 neural populations. We (45) previously reported that CCK does activate cFos expression in a subset of cNTS NA neurons and other phenotypically unidentified cNTS neurons in overnight-fasted rats, but that report and the present study confirm that the activated populations exclude PrRP- and GLP-1-positive neurons. We interpret these data as evidence that PrRP- and GLP-1-positive cNTS neurons are more sensitive to the metabolic consequences of overnight food deprivation compared with other cNTS neurons, including A2 neurons that do not express PrRP.

As confirmed in the present report, GLP-1 neurons are activated to express cFos in fed rats after intraperitoneal CCK and other experimental treatments (including cognitive stressors, mechanical gastric distension, and rapid intake of very large meals) that promote hypophagia (37, 38, 45, 47, 60, 70). However, despite a wealth of evidence that central GLP-1 receptor signaling suppresses food intake and contributes to the hypophagic effects of a variety of experimental treatments in rats and mice (32, 38, 43, 47, 61, 67, 80), causal evidence that GLP-1 neurons contribute to CCK-induced hypophagia or to normal meal-induced satiety is currently lacking.

GRA increases neural and behavioral sensitivity to CCK in fasted rats.

CCK-mediated recruitment of cNTS neurons occurs via activation of glutamatergic vagal afferent fibers (3, 52, 58). Ghrelin signaling inhibits vagal afferent activation and central glutamate release from vagal afferent terminals within the cNTS (17, 21). Since plasma ghrelin levels rise during a fast (69), we hypothesized that ghrelin signaling inhibits vagal afferent input to cNTS neurons during an overnight fast, thereby reducing the ability of CCK to activate GLP-1 and PrRP neurons. Indeed, GRA in DEP rats partially rescued CCK-induced activation of GLP-1 and PrRP neurons, and also increased the hypophagic effect of CCK. The GRA used in our study ([d-Lys3]GHRP-6) crosses the BBB after systemic administration (4); thus, it is unclear whether antagonism of ghrelin receptors expressed at peripheral (21) and/or central sites (17) underlies the observed effects of intraperitoneal GRA to enhance CCK-induced cFos activation and hypophagia in fasted rats.

The ability of GRA to increase CCK-induced neural activation in DEP rats was statistically significant but variable: cFos activation of both neural populations was restored to “fed” levels in some rats, whereas other rats displayed little effect of the GRA + CCK combination (Fig. 2). We speculate that a higher dose of GRA and/or a different time interval between GRA pretreatment and CCK injection might have produced a more consistent “rescue” effect; additional work will be required to test this. Interestingly, cFos activation in GRA + CCK-treated DEP rats was similarly variable within both the GLP-1 and PrRP neural populations, and the proportion of GLP-1 neurons activated to express cFos in individual rats in this treatment group was highly correlated with the proportion of PrRP neurons activated (Fig. 2D). Exceedingly few GLP-1 or PrRP neurons were activated in fasted rats after saline injection, after saline pretreatment followed by CCK, or after GRA alone, evidence that neither the stress associated with handling and intraperitoneal injection nor GRA by itself was sufficient to activate either of these two neural populations in fasted rats. Moreover, GRA followed by CCK was the only intraperitoneal treatment combination that significantly suppressed fasting-induced food intake. Although the behavioral data collected in the GRA + CCK-treated DEP rats (Fig. 4D) were less variable than the cFos data (Fig. 2), results from both experiments implicate endogenous ghrelin signaling in the metabolic tuning of GLP-1 and PrRP neuronal responses to CCK and the metabolic regulation of CCK-induced hypophagia.

The apparent suppressive effect of fasting-induced ghrelin signaling on hindbrain neural activation may occur in concert with fasting-induced increases in another inhibitory signal or decreases in an excitatory signal. For example, in addition to increasing plasma ghrelin and reducing plasma leptin levels (discussed further, in the next section), overnight food deprivation reduces gastric distention, reduces plasma levels of glucose, insulin, and glucagon, and increases circulating levels of the steroid hormone corticosterone (CORT) (19, 53). This last metabolic change is of particular interest, as Herman and colleagues (77, 78) have reported that CORT signaling reduces mRNA expression of the GLP-1 precursor protein preproglucagon within the cNTS. Future studies should investigate whether increased CORT signaling also is sufficient to suppress cFos activation of hindbrain GLP-1 and PrRP neurons in rats after overnight food deprivation.

Leptin administration fails to increase GLP-1 or PrRP neural sensitivity to CCK in fasted rats.

Plasma leptin levels fall markedly in rats during an overnight fast (19), and ample histological (73, 75) and electrophysiological evidence (54, 56) indicates that both central and peripheral leptin signaling enhance the ability of CCK to activate neurons within the cNTS. Leptin and CCK also synergize to reduce dark-onset and fasting-induced food intake in mice (10, 49) and rats (27, 51). In the present study, however, coadministration of leptin with CCK in fasted rats failed to rescue cFos activation in GLP-1 and PrRP neurons (Fig. 1). The negative cFos data reported here are inconsistent with published behavioral data from a study using 48-h food-deprived Wistar rats (51), in which the hypophagic effect of CCK (3 μg/kg body wt ip) was rescued by chronic leptin replacement during the 48-h fasting period (100 μg/kg/day sc). However, a head-to-head comparison of the present study with the previous one reveals a number of protocol differences, including the rat strain, the length of food deprivation, the route/dose/timing of leptin replacement, the dose of CCK, the circadian time of refeeding, and the absence of relevant cFos data in the previous report (51). It seems unlikely that the doses of leptin used in our experiment were too low, since they elicit robust p-STAT3 responses within the cNTS (46), and since even lower doses of leptin are sufficient to enhance CCK-mediated transcriptional events in vagal afferents (23), to reduce food intake (10, 15, 23), to inhibit gastric emptying (14), and to increase sympathetic nervous system activation and lipolysis (64).

It is possible that leptin pretreatment (vs. coadministration) might increase the ability of CCK to activate GLP-1 and PrRP neurons in fasted rats. The coadministration strategy used in the present study was based on in vitro evidence that leptin directly depolarizes vagal afferent neurons and enhances CCK-mediated calcium influx within seconds of application (54, 56) and on in vivo evidence that coadministration of leptin with CCK promotes activation of hypothalamic (but not cNTS) neurons in fasted mice (72). Thus, although our results do not support a link between fasting-induced reductions in leptin signaling and fasting-induced reductions in GLP-1 and PrRP neural sensitivity to exogenous CCK, additional work is needed to strengthen this conclusion.

Perspectives and Significance

Results from the present study support the view that 1) increased ghrelin signaling after overnight food deprivation suppresses the ability of CCK treatment to activate both GLP-1 and PrRP neurons within the rat cNTS and 2) that fasting-induced increases in ghrelin signaling suppress behavioral sensitivity to the hypophagic effect of CCK. We interpret these data as evidence that increased endogenous ghrelin signaling is an important (but presumably not the sole) factor underlying fasting-induced suppression of hindbrain GLP-1 and PrRP neuronal responses to CCK, and also underlying fasting-induced suppression of hypophagic responses to CCK. Notably, fasting-induced increases in ghrelin signaling may similarly alter other behavioral and physiological processes in which GLP-1 and PrRP neurons are implicated (43, 44). For example, central GLP-1 signaling contributes to stress-induced hypophagia (32, 47), overnight fasting blocks or attenuates the ability of cognitive stressors to activate GLP-1 and PrRP neurons (47), and the ability of stressful stimuli to reduce food intake and activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is attenuated during periods of negative energy balance (1, 41, 51, 76). Together, these findings suggest a broader effect of negative energy balance on the activation of hindbrain neural populations that modulate physiology and behavior. An improved mechanistic understanding of how metabolic state impacts these hindbrain neurons could improve not only our knowledge of physiological contributors to ingestive behavior but may also suggest new strategies to prevent and treat stress-related disorders, including anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders.

GRANTS

This research was funded by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-100685 and MH-059911 (to L. Rinaman).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.W.M. and L.R. conceived and designed research; J.W.M. and C.M.E. performed experiments; J.W.M., C.M.E., and L.R. analyzed data; J.W.M. and L.R. interpreted results of experiments; J.W.M. and C.M.E. prepared figures; J.W.M. and L.R. drafted manuscript; J.W.M., C.M.E., and L.R. edited and revised manuscript; J.W.M., C.M.E., and L.R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Some of the data reported in this paper were collected when J. W. Maniscalco was a doctoral student working with L. Rinaman in the Dept. of Neuroscience, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akana SF, Strack AM, Hanson ES, Dallman MF. Regulation of activity in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis is integral to a larger hypothalamic system that determines caloric flow. Endocrinology 135: 1125–1134, 1994. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.3.8070356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akieda-Asai S, Poleni PE, Date Y. Coinjection of CCK and leptin reduces food intake via increased CART/TRH and reduced AMPK phosphorylation in the hypothalamus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 306: E1284–E1291, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00664.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appleyard SM, Marks D, Kobayashi K, Okano H, Low MJ, Andresen MC. Visceral afferents directly activate catecholamine neurons in the solitary tract nucleus. J Neurosci 27: 13292–13302, 2007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3502-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asakawa A, Inui A, Kaga T, Katsuura G, Fujimiya M, Fujino MA, Kasuga M. Antagonism of ghrelin receptor reduces food intake and body weight gain in mice. Gut 52: 947–952, 2003. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bado A, Levasseur S, Attoub S, Kermorgant S, Laigneau JP, Bortoluzzi MN, Moizo L, Lehy T, Guerre-Millo M, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Lewin MJ. The stomach is a source of leptin. Nature 394: 790–793, 1998. doi: 10.1038/29547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagnasco M, Kalra PS, Kalra SP. Ghrelin and leptin pulse discharge in fed and fasted rats. Endocrinology 143: 726–729, 2002. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.2.8743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banks WA, Burney BO, Robinson SM. Effects of triglycerides, obesity, and starvation on ghrelin transport across the blood-brain barrier. Peptides 29: 2061–2065, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Huang W, Jaspan JB, Maness LM. Leptin enters the brain by a saturable system independent of insulin. Peptides 17: 305–311, 1996. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(96)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banks WA, Tschöp M, Robinson SM, Heiman ML. Extent and direction of ghrelin transport across the blood-brain barrier is determined by its unique primary structure. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 302: 822–827, 2002. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.034827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrachina MD, Martínez V, Wang L, Wei JY, Taché Y. Synergistic interaction between leptin and cholecystokinin to reduce short-term food intake in lean mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 10455–10460, 1997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Billington CJ, Levine AS, Morley JE. Are peptides truly satiety agents? A method of testing for neurohumoral satiety effects. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 245: R920–R926, 1983. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1983.245.6.R920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burdyga G, Spiller D, Morris R, Lal S, Thompson DG, Saeed S, Dimaline R, Varro A, Dockray GJ. Expression of the leptin receptor in rat and human nodose ganglion neurones. Neuroscience 109: 339–347, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buyse M, Ovesjö ML, Goïot H, Guilmeau S, Péranzi G, Moizo L, Walker F, Lewin MJ, Meister B, Bado A. Expression and regulation of leptin receptor proteins in afferent and efferent neurons of the vagus nerve. Eur J Neurosci 14: 64–72, 2001. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cakir B, Kasimay O, Devseren E, Yeğen BC. Leptin inhibits gastric emptying in rats: role of CCK receptors and vagal afferent fibers. Physiol Res 56: 315–322, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campfield LA, Smith FJ, Guisez Y, Devos R, Burn P. Recombinant mouse OB protein: evidence for a peripheral signal linking adiposity and central neural networks. Science 269: 546–549, 1995. doi: 10.1126/science.7624778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cecchi M, Khoshbouei H, Javors M, Morilak DA. Modulatory effects of norepinephrine in the lateral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis on behavioral and neuroendocrine responses to acute stress. Neuroscience 112: 13–21, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui RJ, Li X, Appleyard SM. Ghrelin inhibits visceral afferent activation of catecholamine neurons in the solitary tract nucleus. J Neurosci 31: 3484–3492, 2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3187-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cummings DE, Purnell JQ, Frayo RS, Schmidova K, Wisse BE, Weigle DS. A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes 50: 1714–1719, 2001. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dallman MF, Akana SF, Bhatnagar S, Bell ME, Choi S, Chu A, Horsley C, Levin N, Meijer O, Soriano LR, Strack AM, Viau V. Starvation: early signals, sensors, and sequelae. Endocrinology 140: 4015–4023, 1999. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.9.7001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Date Y, Kojima M, Hosoda H, Sawaguchi A, Mondal MS, Suganuma T, Matsukura S, Kangawa K, Nakazato M. Ghrelin, a novel growth hormone-releasing acylated peptide, is synthesized in a distinct endocrine cell type in the gastrointestinal tracts of rats and humans. Endocrinology 141: 4255–4261, 2000. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.11.7757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Date Y, Murakami N, Toshinai K, Matsukura S, Niijima A, Matsuo H, Kangawa K, Nakazato M. The role of the gastric afferent vagal nerve in ghrelin-induced feeding and growth hormone secretion in rats. Gastroenterology 123: 1120–1128, 2002. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Date Y, Toshinai K, Koda S, Miyazato M, Shimbara T, Tsuruta T, Niijima A, Kangawa K, Nakazato M. Peripheral interaction of ghrelin with cholecystokinin on feeding regulation. Endocrinology 146: 3518–3525, 2005. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Lartigue G, Lur G, Dimaline R, Varro A, Raybould H, Dockray GJ. EGR1 Is a target for cooperative interactions between cholecystokinin and leptin, and inhibition by ghrelin, in vagal afferent neurons. Endocrinology 151: 3589–3599, 2010. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dodd GT, Worth AA, Nunn N, Korpal AK, Bechtold DA, Allison MB, Myers MG Jr, Statnick MA, Luckman SM. The thermogenic effect of leptin is dependent on a distinct population of prolactin-releasing peptide neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamus. Cell Metab 20: 639–649, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edwards CM, Strother J, Zheng H, Rinaman L. Amphetamine-induced activation of neurons within the rat nucleus of the solitary tract. Physiol Behav 204: 355–363, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellacott KLJ, Lawrence CB, Rothwell NJ, Luckman SM. PRL-releasing peptide interacts with leptin to reduce food intake and body weight. Endocrinology 143: 368–374, 2002. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.2.8608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emond M, Schwartz GJ, Ladenheim EE, Moran TH. Central leptin modulates behavioral and neural responsivity to CCK. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 276: R1545–R1549, 1999. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.R1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Genn RF, Tucci SA, Thomas A, Edwards JE, File SE. Age-associated sex differences in response to food deprivation in two animal tests of anxiety. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 27: 155–161, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(03)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanson ES, Bradbury MJ, Akana SF, Scribner KS, Strack AM, Dallman MF. The diurnal rhythm in adrenocorticotropin responses to restraint in adrenalectomized rats is determined by caloric intake. Endocrinology 134: 2214–2220, 1994. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.5.8156924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hay-Schmidt A, Helboe L, Larsen PJ. Leptin receptor immunoreactivity is present in ascending serotonergic and catecholaminergic neurons of the rat. Neuroendocrinology 73: 215–226, 2001. doi: 10.1159/000054638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes MR, Bradley L, Grill HJ. Endogenous hindbrain glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor activation contributes to the control of food intake by mediating gastric satiation signaling. Endocrinology 150: 2654–2659, 2009. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holt MK, Richards JE, Cook DR, Brierley DI, Williams DL, Reimann F, Gribble FM, Trapp S. Preproglucagon neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract are the main source of brain GLP-1, mediate stress-induced hypophagia, and limit unusually large intakes of food. Diabetes 68: 21–33, 2019. doi: 10.2337/db18-0729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huo L, Gamber KM, Grill HJ, Bjørbaek C. Divergent leptin signaling in proglucagon neurons of the nucleus of the solitary tract in mice and rats. Endocrinology 149: 492–497, 2008. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inoue K, Zorrilla EP, Tabarin A, Valdez GR, Iwasaki S, Kiriike N, Koob GF. Reduction of anxiety after restricted feeding in the rat: implication for eating disorders. Biol Psychiatry 55: 1075–1081, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinzig KP, D’Alessio DA, Herman JP, Sakai RR, Vahl TP, Figueiredo HF, Murphy EK, Seeley RJ. CNS glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors mediate endocrine and anxiety responses to interoceptive and psychogenic stressors. J Neurosci 23: 6163–6170, 2003. [Erratum in: J Neurosci 23: 8158, 2003.] doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06163.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature 402: 656–660, 1999. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kreisler AD, Davis EA, Rinaman L. Differential activation of chemically identified neurons in the caudal nucleus of the solitary tract in non-entrained rats after intake of satiating vs. non-satiating meals. Physiol Behav 136: 47–54, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kreisler AD, Rinaman L. Hindbrain glucagon-like peptide-1 neurons track intake volume and contribute to injection stress-induced hypophagia in meal-entrained rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 310: R906–R916, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00243.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawrence CB, Celsi F, Brennand J, Luckman SM. Alternative role for prolactin-releasing peptide in the regulation of food intake. Nat Neurosci 3: 645–646, 2000. doi: 10.1038/76597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawrence CB, Ellacott KLJ, Luckman SM. PRL-releasing peptide reduces food intake and may mediate satiety signaling. Endocrinology 143: 360–367, 2002. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.2.8609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lennie TA, McCarthy DO, Keesey RE. Body energy status and the metabolic response to acute inflammation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 269: R1024–R1031, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.5.R1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luckman SM. Fos-like immunoreactivity in the brainstem of the rat following peripheral administration of cholecystokinin. J Neuroendocrinol 4: 149–152, 1992. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1992.tb00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maniscalco JW, Kreisler AD, Rinaman L. Satiation and stress-induced hypophagia: examining the role of hindbrain neurons expressing prolactin-releasing Peptide or glucagon-like Peptide 1. Front Neurosci 6: 199, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maniscalco JW, Rinaman L. Interoceptive modulation of neuroendocrine, emotional, and hypophagic responses to stress. Physiol Behav 176: 195–206, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maniscalco JW, Rinaman L. Overnight food deprivation markedly attenuates hindbrain noradrenergic, glucagon-like peptide-1, and hypothalamic neural responses to exogenous cholecystokinin in male rats. Physiol Behav 121: 35–42, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maniscalco JW, Rinaman L. Systemic leptin dose-dependently increases STAT3 phosphorylation within hypothalamic and hindbrain nuclei. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 306: R576–R585, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00017.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maniscalco JW, Zheng H, Gordon PJ, Rinaman L. Negative energy balance blocks neural and behavioral responses to acute stress by “silencing” central glucagon-like peptide 1 signaling in rats. J Neurosci 35: 10701–10714, 2015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3464-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maruyama M, Matsumoto H, Fujiwara K, Noguchi J, Kitada C, Fujino M, Inoue K. Prolactin-releasing peptide as a novel stress mediator in the central nervous system. Endocrinology 142: 2032–2038, 2001. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.5.8118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matson CA, Wiater MF, Kuijper JL, Weigle DS. Synergy between leptin and cholecystokinin (CCK) to control daily caloric intake. Peptides 18: 1275–1278, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(97)00138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsumoto H, Maruyama M, Noguchi J, Horikoshi Y, Fujiwara K, Kitada C, Hinuma S, Onda H, Nishimura O, Inoue K, Fujino M. Stimulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone-mediated adrenocorticotropin secretion by central administration of prolactin-releasing peptide in rats. Neurosci Lett 285: 234–238, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McMinn JE, Sindelar DK, Havel PJ, Schwartz MW. Leptin deficiency induced by fasting impairs the satiety response to cholecystokinin. Endocrinology 141: 4442–4448, 2000. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mönnikes H, Lauer G, Arnold R. Peripheral administration of cholecystokinin activates c-fos expression in the locus coeruleus/subcoeruleus nucleus, dorsal vagal complex and paraventricular nucleus via capsaicin-sensitive vagal afferents and CCK-A receptors in the rat. Brain Res 770: 277–288, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)00865-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moran TH, Bi S. Hyperphagia and obesity in OLETF rats lacking CCK-1 receptors. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 361: 1211–1218, 2006. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peters JH, Karpiel AB, Ritter RC, Simasko SM. Cooperative activation of cultured vagal afferent neurons by leptin and cholecystokinin. Endocrinology 145: 3652–3657, 2004. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peters JH, Ritter RC, Simasko SM. Leptin and CCK modulate complementary background conductances to depolarize cultured nodose neurons. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C427–C432, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00439.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peters JH, Simasko SM, Ritter RC. Modulation of vagal afferent excitation and reduction of food intake by leptin and cholecystokinin. Physiol Behav 89: 477–485, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Picó C, Sánchez J, Oliver P, Palou A. Leptin production by the stomach is up-regulated in obese (fa/fa) Zucker rats. Obes Res 10: 932–938, 2002. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raybould HE, Gayton RJ, Dockray GJ. Mechanisms of action of peripherally administered cholecystokinin octapeptide on brain stem neurons in the rat. J Neurosci 8: 3018–3024, 1988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-03018.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rinaman L. Hindbrain noradrenergic lesions attenuate anorexia and alter central cFos expression in rats after gastric viscerosensory stimulation. J Neurosci 23: 10084–10092, 2003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-31-10084.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rinaman L. Interoceptive stress activates glucagon-like peptide-1 neurons that project to the hypothalamus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 277: R582–R590, 1999. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.2.R582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rinaman L, Rothe EE. GLP-1 receptor signaling contributes to anorexigenic effect of centrally administered oxytocin in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 283: R99–R106, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00008.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schwartz GJ, McHugh PR, Moran TH. Gastric loads and cholecystokinin synergistically stimulate rat gastric vagal afferents. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 265: R872–R876, 1993. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.4.R872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Serrats J, Sawchenko PE. CNS activational responses to staphylococcal enterotoxin B: T-lymphocyte-dependent immune challenge effects on stress-related circuitry. J Comp Neurol 495: 236–254, 2006. doi: 10.1002/cne.20872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shen J, Tanida M, Niijima A, Nagai K. In vivo effects of leptin on autonomic nerve activity and lipolysis in rats. Neurosci Lett 416: 193–197, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith GP, Jerome C, Cushin BJ, Eterno R, Simansky KJ. Abdominal vagotomy blocks the satiety effect of cholecystokinin in the rat. Science 213: 1036–1037, 1981. doi: 10.1126/science.7268408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Takayanagi Y, Matsumoto H, Nakata M, Mera T, Fukusumi S, Hinuma S, Ueta Y, Yada T, Leng G, Onaka T. Endogenous prolactin-releasing peptide regulates food intake in rodents. J Clin Invest 118: 4014–4024, 2008. doi: 10.1172/JCI34682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Terrill SJ, Maske CB, Williams DL. Endogenous GLP-1 in lateral septum contributes to stress-induced hypophagia. Physiol Behav 192: 17–22, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Toshinai K, Mondal MS, Nakazato M, Date Y, Murakami N, Kojima M, Kangawa K, Matsukura S. Upregulation of ghrelin expression in the stomach upon fasting, insulin-induced hypoglycemia, and leptin administration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 281: 1220–1225, 2001. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tschöp M, Smiley DL, Heiman ML. Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature 407: 908–913, 2000. doi: 10.1038/35038090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vrang N, Phifer CB, Corkern MM, Berthoud HR. Gastric distension induces c-Fos in medullary GLP-1/2-containing neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 285: R470–R478, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00732.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wall KD, Olivos DR, Rinaman L. High fat diet attenuates cholecystokinin-induced cFos activation of prolactin-releasing peptide-expressing A2 noradrenergic neurons in the caudal nucleus of the solitary tract. Neuroscience S0306-4522(19)30647-5, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang L, Barachina MD, Martínez V, Wei JY, Taché Y. Synergistic interaction between CCK and leptin to regulate food intake. Regul Pept 92: 79–85, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0167-0115(00)00153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang L, Martínez V, Barrachina MD, Taché Y. Fos expression in the brain induced by peripheral injection of CCK or leptin plus CCK in fasted lean mice. Brain Res 791: 157–166, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Watson RE Jr, Wiegand SJ, Clough RW, Hoffman GE. Use of cryoprotectant to maintain long-term peptide immunoreactivity and tissue morphology. Peptides 7: 155–159, 1986. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(86)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Williams DL, Baskin DG, Schwartz MW. Hindbrain leptin receptor stimulation enhances the anorexic response to cholecystokinin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R1238–R1246, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00182.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Youngblood BD, Ryan DH, Harris RB. Appetitive operant behavior and free-feeding in rats exposed to acute stress. Physiol Behav 62: 827–830, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(97)00245-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang R, Jankord R, Flak JN, Solomon MB, D’Alessio DA, Herman JP. Role of glucocorticoids in tuning hindbrain stress integration. J Neurosci 30: 14907–14914, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0522-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang R, Packard BA, Tauchi M, D’Alessio DA, Herman JP. Glucocorticoid regulation of preproglucagon transcription and RNA stability during stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5913–5918, 2009. [Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 13636, 2009.] doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808716106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 372: 425–432, 1994. doi: 10.1038/372425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zheng H, Reiner DJ, Hayes MR, Rinaman L. Chronic suppression of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP1R) mRNA translation in the rat bed nucleus of the stria terminalis reduces anxiety-like behavior and stress-induced hypophagia, but prolongs stress-induced elevation of plasma corticosterone. J Neurosci 39: 2649–2663, 2019. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2180-18.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zheng H, Stornetta RL, Agassandian K, Rinaman L. Glutamatergic phenotype of glucagon-like peptide 1 neurons in the caudal nucleus of the solitary tract in rats. Brain Struct Funct 220: 3011–3022, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0841-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]