CASE REPORT

An otherwise healthy 23‐year‐old woman presented with facial symmetrical erythema and slight itching lasting 4 days. Symptoms developed after wearing a KN95 (FFP2 equivalent) mask for 2 days to prevent contracting SARS‐CoV‐2. One day before, the patient had consulted the emergency department and a presumptive diagnosis of acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus by the general emergency doctors was made because of her gender and facial symmetrical erythema. However, the physical examination and medical history of the patient and her family were unremarkable. Blood and urine routine tests and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate were negative and normal, respectively. The specific autoantibodies and complement were also negative.

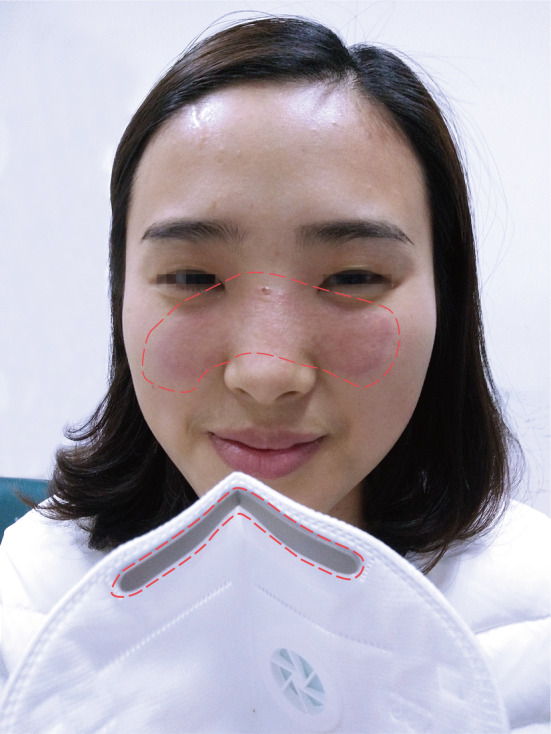

In our dermatology clinic, given the use of the mask and the shape of the lesion resembling that of the sponge strip on the contact surface inside the mask (Figure 1), the patient was provisionally diagnosed with mask‐induced allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). After 3 days of anti‐allergic treatment (oral desloratadine and topical desonide cream), the lesions almost completely disappeared. The patient switched to other masks without sponge strips which were tolerated. No recurrence was found after 3‐month follow‐up.

FIGURE 1.

Symmetrical erythema centered on the nose bridge without blisters and scales. The highlighted area shows the same pattern of rash as the sponge strip on the contact surface of the mask

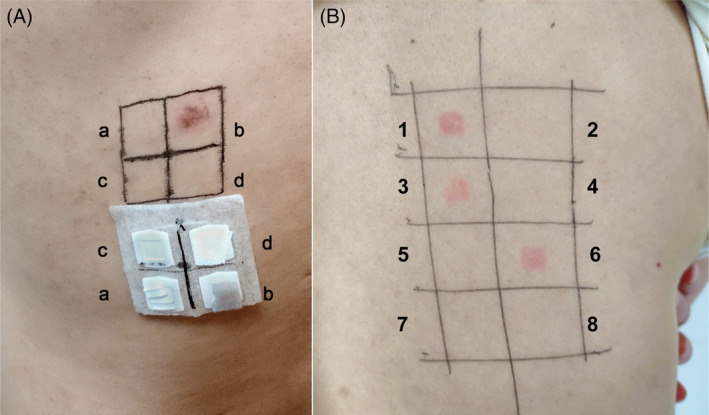

Patch tests were applied on the upper back and occluded for 2 days with the TRUE Test (Mekos Laboratories, Hillerød, Denmark), and readings were made on day (D)2, D4, and D7 with negative results. 1 Additional patch tests using IQ chambers (Chemotechnique Diagnostics, Vellinge, Sweden) were performed with pieces of sponge taken from this mask. Tests were read on D2 and D4 according to ESCD guidelines and showed a positive reaction to the sponge (++) at D4, while no reaction was seen in three self‐controls (D4) (Figure 2A). Ten control volunteers were patch‐tested the same way with all negative results. The patient was then tested with the isocyanate series (Chemotechnique Diagnostics) and showed a positive reaction to toluene‐2,4‐diisocyanate (TDI) 2.0% pet., 4,4'‐diaminodiphenylmethane (MDA) 0.5% pet., and hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI) 0.1% pet. on day D2 (++) and D4 (++) (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

(A) Patch tests showed a positive reaction (++) to the sponge strip (b) and three negative results, including metal strip (a), blank control (c), and polypropylene spun bond non‐woven fabric (d) on day 4. (B) On D4, positive patch test reactions to TDI 2.0% pet. (1), MDA 0.5% pet. (3), and HDI 0.1% pet. (6)

DISCUSSION

Polyurethanes, which are being used increasingly in the production of various products, including the sponge strip inside the mask, are produced by the reaction of diisocyanates and may cause ACD or precipitate asthma attacks.2, 3 Polyurethane as the fully cured polymer is thought not to be a sensitizer. However, residual cross‐linkers have been reported to cause allergic reactions, such as TDI, HDI, MDA, or MDI, which are particularly responsible for respiratory symptoms, and less frequently for ACD.4, 5 To our knowledge, this is the first case report of ACD to a polyurethane sponge inside a mask.

Facial ACD can mimic other diseases, such as acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, seborrheic dermatitis, and sarcoidosis, especially if occurring on specific body areas or evaluated by a nondermatologist. At present, the use of masks is very common due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. The incidence of allergies caused by mask contact may increase. Meanwhile, during the epidemic, all medical staff need to wear medical masks much longer than the general population, which may easily lead to local impression, redness, erosion, and even induce eczema or worsen rosacea. In this special period, all doctors, especially emergency doctors or general practitioners who are responsible for the main admissions during the pandemic, must be vigilant to help avoid delaying diagnosis, unnecessary tests, and causing panic among patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Zhen Xie: Conceptualization; investigation; resources; writing‐original draft. Xin Yang: Conceptualization; investigation; project administration; resources; writing‐review and editing. Hao Zhang: Conceptualization; investigation; project administration; resources; supervision; writing‐review and editing.

Xie Z, Yang Y‐X, Zhang H. Mask‐induced contact dermatitis in handling COVID‐19 outbreak. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;83:166–167. 10.1111/cod.13599

REFERENCES

- 1. Johansen JD, Aalto‐Korte K, Agner T, et al. European Society of Contact Dermatitis guideline for diagnostic patch testing ‐ recommendations on best practice. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73(4):195‐221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dykewicz MS. Occupational asthma: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(3):519‐528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Krone CA, Klingler TD. Isocyanates, polyurethane and childhood asthma. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16(5):368‐379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Litvinov IV, Sugathan P, Cohen BA. Recognizing and treating toilet‐seat contact dermatitis in children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):e419‐e422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Milanesi N, Gola M, Francalanci S. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by a polyurethane catheter. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79(5):313‐314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]