Dear Editor,

COVID‐19, a novel coronavirus, has spread throughout the world. Because of exponential growth, social distancing is a critical strategy to decrease transmission. Thus, educational medical communities from many countries have transitioned to online didactics. 1 Recommendations to cancel all non‐urgent visits have been proposed. 2 Our dermatology department has cancelled all elective outpatient visits and surgeries. Consequently, trainees’ surgical skills have been severely affected. To continue our educational programme, we have implemented measures to help our trainees continue learning and maintaining surgical skills.

We continued our educational programme with a general review of basic and advanced dermatologic surgery using PowerPoint presentations using a web‐based video conferencing tool. Professors share their knowledge and experiences with trainees and answer any questions. Afterwards, professors apply a hypothetical case scenario so the surgical trainee can decide the surgical approach [Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) or conventional wide‐margin excision (WME)] using a simulator bust model (Diaphanous Zsa Zsa, DermSurg Scientific, Dayton, OH, USA).

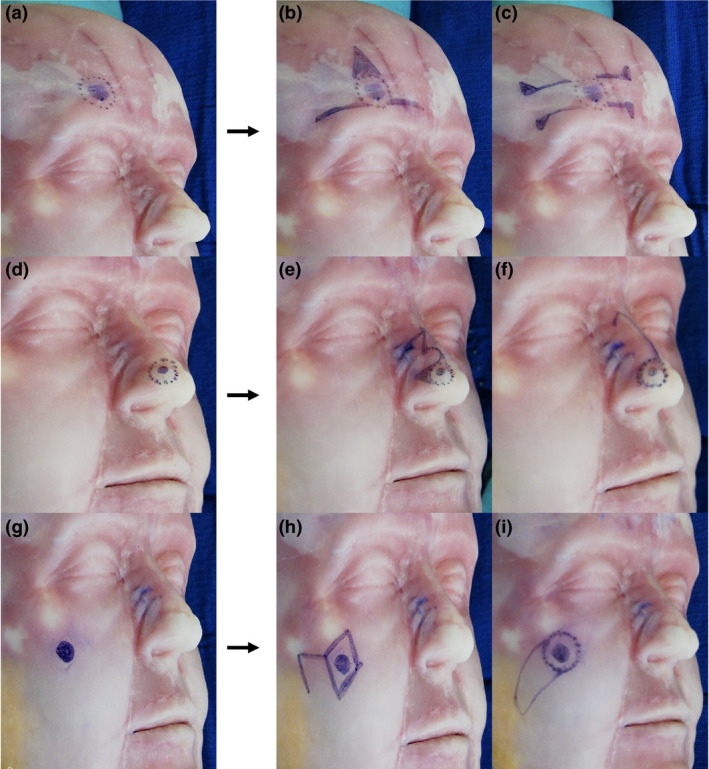

Residents design multiple flaps and practise surgical skills in a life‐like scenario (Fig. 1) and place the simulator akin to how patients are normally positioned for surgery. Then, with a non‐permanent marker they draw a hypothetical skin defect. Depending on the size and location of the cancer, they design and discuss different possible reconstruction flaps. Multiple flap designs are then drawn by the trainees to see which is best suited. To reassure complete comprehension, trainees explain the concepts behind every flap and are assessed by their professors. Drawings from conventional surgical markers are easily erased from the bust models with isopropyl alcohol allowing a quick turnaround time for the next case.

Figure 1.

Example of how surgical trainees practise dermatologic surgery with a simulator (Diaphanous Zsa Zsa, DermSurg Scientific). In this example, surgical trainees were given a hypothetical case scenario in which the patient was going to have a wide‐margin excision surgery for a basal cell carcinoma in three different locations: forehead, nose and cheek. After the session, trainees and professor have a discussion session to improve flap designs and repair methods of the hypothetical case. (a) A 1‐cm cutaneous malignancy in the forehead above the right eyebrow is drawn with a 4‐mm excision margin. (b) O‐T flap is designed for reconstruction. Standing cutaneous deformity (SCD) was drawn for excision. (c) Bilateral unipedicle advancement flaps are combined to repair defect resulting in horizontally oriented H‐shaped wound closure (H‐plasty). Burrow triangles were drawn for excision for flap advancement. (d) A 0.70‐cm cutaneous malignancy in the nose involving lateral wall and alar lobule was drawn with a 4‐mm excision margin. (e) Design of a bilobed flap for reconstruction with SCD was drawn. (f) A modified rotation dorsal flap is drawn. A back cut for flap advancement is shown. (g) A 0.9‐cm cutaneous malignancy in the mandibular location is drawn. (h) The classic rhombic flap (Limberg) with a 4‐mm margin is designed to repair the defect. (i) An island advancement flap with a skin pedicle is designed to repair the defect.

The combined use of simulation‐based education and digital technologies for dermatologic surgery has been previously reported. 3 , 4 Nicholas et al. 5 carried out a pilot study and reported that learners were receptive to the use of simulators in their dermatologic training after a 2‐day surgical symposium. More than 90% of the participants agreed that simulators were helpful. Additionally, more than 75% of the participants agreed that simulators were useful in acquiring, refining, assessing and learning these skills. Notably, 90.9% of the participants thought that training using simulators should be mandatory in their residency programme.

It is important to clarify that this educational experience is new for everyone, and we acknowledge that any recommendations we propose are likely to shift in the coming weeks as the advancement of online medical education evolves. Despite the need to polish and improve the dermatological surgery programme with simulators in our department, our experience indicates that surgical trainees learn to train their minds to consider the different flaps and possible reconstructions with 1‐hour weekly practices. Our main goal is that when the COVID‐19 contingency ends, our trainees will have the confidence and mental ability to treat patients. We want to emphasize that learning and/or practicing with simulators will never substitute a real patient. We remind our trainees that each patient’s case is unique and it is necessary consider the personal history (e.g. smoking, anticoagulants), skin characteristics (elasticity, sun damage), and size and location of the lesion, among others, in order to evaluate the type of surgery (MMS vs. wide‐margin excision), surgical margins and reconstruction method for the defect once clear margins have been obtained. While cost and availability of dermatologic surgery professors remain the main limitations, 5 efforts should be made during this contingency to advance medical education. The combined use of web‐based video conferencing tools and simulators for dermatologic surgery education opens an opportunity for curricular innovations and transformation of medical trainee programmes.

Funding source

This article has no funding source.

References

- 1. Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID‐19. JAMA 2020. 10.1001/jama.2020.5227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kwatra SG, Sweren RJ, Grossberg AL. Dermatology practices as vectors for COVID‐19 transmission: a call for immediate cessation of non‐emergent dermatology visits. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82: e179–e180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guerrero‐Gonzalez GA, Ocampo‐Garza J, Vazquez‐Martinez O, Garza‐Rodriguez V, Ocampo‐Candiani J. Combined use of simulation and digital technologies for teaching dermatologic surgery. J Eur Acad Dermatol 2016; 30: e175–e176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu KJ, Tkachenko E, Waldman A et al. A video‐based, flipped classroom, simulation curriculum for dermatologic surgery: a prospective, multi‐institution study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019; 81: 1271–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nicholas L, Toren K, Bingham J, Marquart J. Simulation in dermatologic surgery: a new paradigm in training. Dermatol Surg. 2013; 39: 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]