Abstract

Patients with cardiovascular disease and, namely, heart failure are more susceptible to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and have a more severe clinical course once infected. Heart failure and myocardial damage, shown by increased troponin plasma levels, occur in at least 10% of patients hospitalized for COVID‐19 with higher percentages, 25% to 35% or more, when patients critically ill or with concomitant cardiac disease are considered. Myocardial injury may be elicited by multiple mechanisms, including those occurring with all severe infections, such as fever, tachycardia, adrenergic stimulation, as well as those caused by an exaggerated inflammatory response, endotheliitis and, in some cases, myocarditis that have been shown in patients with COVID‐19. A key role may be that of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infects human cells binding to angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), an enzyme responsible for the cleavage of angiotensin II into angiotensin 1–7, which has vasodilating and anti‐inflammatory effects. Virus‐mediated down‐regulation of ACE2 may increase angiotensin II stimulation and contribute to the deleterious hyper‐inflammatory reaction of COVID‐19. On the other hand, ACE2 may be up‐regulated in patients with cardiac disease and treated with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. ACE2 up‐regulation may increase the susceptibility to COVID‐19 but may be also protective vs. angiotensin II‐mediated vasoconstriction and inflammatory activation. Recent data show the lack of untoward effects of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers for COVID‐19 infection and severity. Prospective trials are needed to ascertain whether these drugs may have protective effects.

Keywords: COVID‐19, Heart failure, Angiotensin II

Introduction

In late December 2019, an outbreak of viral pneumonia was reported in Wuhan, Hubei, China and rapidly affected several countries becoming a pandemic disorder. The pathogen is a novel enveloped, positive stranded RNA betacoronavirus, provisionally named 2019 novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) and subsequently officially named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). 1 SARS‐CoV‐2 is one of the few pathogenic coronaviruses to humans, along with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS‐CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS‐CoV). SARS‐CoV was first isolated in China in 2002, while MERS‐CoV was detected in Saudi Arabia in 2012. 2 , 3 They both caused respiratory syndromes in humans and were responsible for several victims worldwide. SARS‐CoV‐2 is the cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), the most recent, lethal and widespread pandemic of current times.

Although COVID‐19 has been initially associated with respiratory symptoms, it has become rapidly clear that it may affect multiple organs including the heart. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 This is shown by the high prevalence of comorbidities involving the cardiovascular system as well as by their dramatic impact on patients' outcomes in COVID‐19. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 More recent studies have shown the prominent role of heart failure (HF) both as a risk factor for a more severe clinical course and for increased mortality and as a possible consequence of COVID‐19 related myocardial damage. 5 , 17

The aim of this review is to describe the role of cardiac injury and HF in COVID‐19, its pathogenetic mechanisms and potential implications for treatment, including the use of drugs affecting the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system: angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).

COVID‐19 and cardiovascular comorbidity

The clinical presentation of COVID‐19 is extremely variable. It may be asymptomatic or cause mild symptoms such as fever, dry cough and fatigue. Other patients develop severe pneumonia, which can eventually cause acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and death. First reports already showed a high prevalence of comorbidities and their association with severity of COVID‐19 and increased mortality. 10 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 The role of cardiovascular disease seemed more important, among different comorbidities. In a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the overall case‐fatality rate of COVID‐19 was 2.3% (1023 deaths among 44 672 confirmed cases), but it rose up to 10.5% for those with pre‐existing cardiovascular disease, 7.3% for diabetes, 6.3% for chronic respiratory disease and 6.0% for hypertension. 23 No more than a generic definition of cardiovascular comorbidities was, however, used in most of these reports and the contribution of each condition, including HF, was unsettled. 10 , 13 , 18 , 20 Current data are summarized in Table 1. 11 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27

Table 1.

Prevalence of cardiovascular and respiratory comorbidities in COVID‐19 patients

| Study | Patients, n | Males, % | Age, yearsa | HBP, % | Diabetes, % | CV disease, % | HF, % | Respiratory disorder, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al. 21 | 41 | 73 | 49 [41–58] | 15.0 | 20.0 | 15.0 | – | 2.0 |

| Liu et al. 14 | 137 | 45 | 57 [20–83] | 9.5 | 10.2 | 7.3 | – | 1.5 |

| Wang et al. 12 | 138 | 54 | 56 [42–68] | 31.2 | 10.1 | 14.5 | – | 2.9 |

| Zhang et al. 15 | 140 | 51 | 57 [25–87] | 30.0 | 12.1 | 5.0 | – | 1.4 |

| Guan et al. 18 | 1099 | 58 | 47 [35–58] | 15.0 | 7.4 | 2.5 | – | 1.1 |

| Arentz et al. 11 | 21 | 52 | 70 [43–92] | – | 33.3 | 42.9 | 42.9 | 33.3 |

| Zhou et al. 20 | 191 | 62 | 56 [46–67] | 30.4 | 18.8 | 7.9 | – | 3.1 |

| Mo et al. 16 | 155 | 55 | 54 [42–66] | 23.9 | 9.7 | 9.7 | – | 3.2 |

| Yang et al. 19 | 52 | 67 | 60 ± 13 | – | 17.3 | 9.6 | – | 7.7 |

| Shi et al. 24 | 416 | 49 | 64 [21–95] | 30.5 | 14.4 | 10.6 | 4.1 | 2.9 |

| Guo et al. 25 | 187 | 49 | 58 ± 14 | 32.6 | 15.0 | 15.5 | – | 2.1 |

| Chen et al. 26 | 274 | 62 | 62 [44–70] | 34.0 | 17.1 | 8.4 | 0.4 | 6.6 |

| Mancia et al. 27 | 6272 | 63 | 68 ± 13 | – | 13.7 | 30.1 | 5.1 | 10.4 |

CV, cardiovascular; HBP, high blood pressure; HF, heart failure.

Median [interquartile range] or mean ± standard deviation.

Acute myocardial injury during COVID‐19

As in the case of many other acute conditions, myocardial injury during COVID‐19 may be asymptomatic and can be detected only by laboratory markers. Observational studies of hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 have detected myocardial injury through troponin levels and defined it as their increase above the 99th percentile upper reference limit. Cardiac troponin levels were increased in 8% to 12% of unselected COVID‐19 cases 12 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 25 , 28 and their percentage rose up to 23% to 33% in critically ill patients with a further rise when those with concomitant cardiac disease are considered (Table 2). 12 , 17 , 19 , 20 Most studies and one meta‐analysis showed their independent prognostic role for in‐hospital mortality. 17 , 24 , 25 , 29 Few studies evaluated also N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) plasma levels and found them higher in patients with myocardial injury, although not independently related with outcomes (Table 2). 24 , 25 , 28

Table 2.

Prevalence of heart failure and laboratory signs of cardiac injury or dysfunction and risk of in‐hospital death in COVID‐19 patients

| Study | Patients, n | Males, % | Age, yearsa | HF, % | Deaths, HF vs. non‐HF, % | Elevated troponin, % | Deaths, high vs. low troponin, % | Elevated NPs, % | Deaths, high vs. low NPs, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al. 21 | 41 | 73 | 49 [41–58] | – | – | 12.2 | 80.0 vs 25.0b | – | – |

| Shi et al. 24 | 416 | 49 | 64 [21–95] | 4.1 | – | 19.7 | 51.2 vs. 4.5 | – | – |

| Guo et al. 25 | 187 | 49 | 58 ± 14 | – | – | 27.8 | 59.6 vs. 8.9 | – | – |

| Zhou et al. 20 | 191 | 62 | 56 [46–67] | – | – | 17.2 | 95.8 vs. 22.3 | – | – |

| Chen et al. 26 |

274 |

62 | 62 [44–70] | 0.4 | – | 40.8 | 81.9 vs. 21.7 | 49.1 | 80.0 vs. 13.6 |

| Wei et al. 28 | 101 | 54 | 49 [34–62] | – | – | 15.8 | 18.8 vs. 0 | – | – |

| Inciardi et al. 17 | 99 | 81 | 67 ± 12 | 21.2 | 57.1 vs. 17.9 | – | – | – | – |

Deaths are in‐hospital deaths. Numbers are percentage of patients died.

HF, heart failure; NP, natriuretic peptide.

Median [interquartile range] or mean ± standard deviation.

Data are for patients who required intensive care unit care.

In other cases, cardiac involvement may be clinically evident. In addition to chest pain, suggestive of myocardial ischaemia or myocarditis, and palpitations, patients may present with acute HF. After ARDS and sepsis, HF was the most frequent cause of death in a series of 113 patients who died with COVID‐19. 26 Similar, in the series by Zhou et al., 20 HF was the fourth most frequent complication of COVID‐19, after sepsis, ARDS and respiratory failure, and developed in 23% of patients, 52% in non‐survivors vs. 12% of survivors. Severe acute HF or end‐stage HF has been described as the main clinical manifestation of COVID‐19 in other smaller series of patients or case reports. 30 , 31 , 32 , 33

Cardiac complications, including hypotension, HF and cardiomegaly, were already reported in SARS‐CoV infections. 34 Rabbit models of dilated cardiomyopathy were also described after coronavirus infection. They presented increased heart weight, biventricular dilatation, myocyte hypertrophy, myocardial fibrosis and myocarditis with histopathological signs of interstitial and replacement fibrosis. 35 In COVID‐19, HF or worsening of cardiac dysfunction may develop as a consequence of myocardial damage or as acute myocarditis. This last diagnosis is, however, controversial and often difficult.

So far, few cases of COVID‐19 related acute myocarditis have been described in the literature. 31 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 38 Although rare, their presentation might be severe with hypotension and low cardiac output requiring inotropic therapy. Cardiac magnetic resonance may show diffuse ventricular wall thickening and oedema. However, endomyocardial biopsy may show different degrees of myocardial inflammation and limited or absent myocardial necrosis. 31 , 32 , 36 , 37 , 38 Among two patients who underwent endomyocardial biopsy, the criteria for acute myocarditis were met in only one case. 37 In the other case, SARS‐CoV‐2 was shown although within macrophages, but not in cardiomyocytes, and biopsy showed only low‐grade interstitial myocardial inflammation and aspecific changes of cardiac myocytes with myofibrillar lysis and lipid droplets. 32 These data show that the virus can reside within the heart but do not prove that it has a direct pathogenetic role. 6 , 39 Thus, although a few cases of direct virus‐related myocarditis may exist, several mechanisms other than viral infection alone are responsible for myocardial injury in most patients. 5 , 6 , 39 , 40 , 41

As for SARS‐CoV, a viraemic response may occur with SARS‐CoV‐2 shedding and migration from the lungs to other organs, possible via the vascular route. This is also consistent with the large expression of angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the tissue receptor of SARS‐CoV‐2 (see below), in the vascular system 42 as well as with the finding of acute endotheliitis in patients with COVID‐19. 41 , 43 , 44

Mechanisms of myocardial damage in COVID‐19

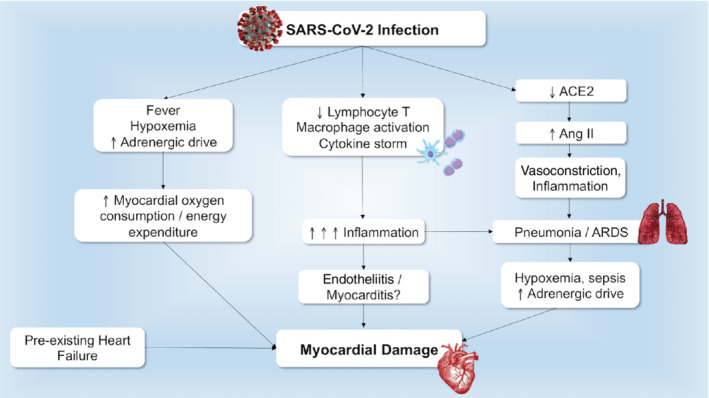

COVID‐19 may cause myocardial damage through different mechanisms, all independent of direct effects of viral infection. These are summarized in Figure 1 and Table 3. 12 , 20 , 24 , 25 , 34 , 38 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 First, there are aspecific mechanisms shared by COVID‐19 with other severe infections (Table 3). 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 COVID‐19 has general deleterious effects such as those caused by fever, sympathetic activation and tachycardia with increased myocardial oxygen consumption and energy expenditure. 47 Prolonged bed rest, another general consequence of severe infection, predisposes to thromboembolic events, a major complication of COVID‐19. 52 Hypoxaemia, another hallmark of COVID‐19, is associated with enhanced oxidative stress with reactive oxygen species production, intracellular acidosis, mitochondrial damage and cell death. 12 , 29 , 47 , 51

Figure 1.

Underlying mechanisms leading to acute myocardial injury in COVID‐19. Different mechanisms lead to cardiac damage in patients with COVID‐19, including general mechanisms related to the infection, immune response, and angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) down‐regulation. Previous cardiac disease provides an unfavourable substrate. Ang II, angiotensin II; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Table 3.

Mechanisms leading to myocardial injury during infective conditions including COVID‐19

| Study, year | Disease | Patients, n | Design | Mechanisms | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madjid et al., 2007 45 | Influenza | 34 892 | Retrospective pathology | Inflammation, platelet activation, endothelial dysfunction | Increased risk of MI and ischaemic cardiomyopathy |

| Corrales‐Medina et al., 2015 46 | Pneumonia | 1773 | Observational prospective | Inflammation, hypercoagulation | Increased risk of CV disease (MI, stroke, and CAD) |

| Violi et al., 2017 47 | Pneumonia | 1182 | Observational prospective | Fever, inflammation, sympathetic activation, hypoxaemia | Increased risk of HF, AF |

| Milbrandt et al., 2009 48 | Pneumonia, sepsis | 939 | Observational prospective | Inflammation, endothelial dysfunction | Increased risk of coagulation abnormalities |

| Violi et al., 2015 49 | Pneumonia | 432 | Observational prospective | Inflammation | Increased risk of AF and HF via oxidative stress |

| Yu et al., 2006 34 | SARS‐CoV disease | 121 | Retrospective | Direct viral damage, inflammation, therapy‐related (corticosteroids, ribavirin) | Tachycardia, arrhythmia, hypotension, cardiomegaly, LV systolic dysfunction |

| Li et al., 2003 50 | SARS‐CoV disease | 46 | Observational prospective | Inflammation, direct viral damage | Acute LV diastolic impairment |

|

Takasu et al., 2013 51 |

Sepsis | 44 | Post‐mortem | Inflammation, hypoxaemia, vasoconstriction | Myocardial ischaemia with mitochondrial damage |

| Shi et al., 2020 24 | COVID‐19 | 416 | Retrospective | Inflammation, direct viral damage, endothelial dysfunction, hypercoagulation | Increased risk of myocardial damage |

| Zhou et al., 2020 20 | COVID‐19 | 191 | Retrospective | Inflammation, hypercoagulation, direct viral damage | Increased risk of myocardial injury |

| Guo et al., 2020 25 | COVID‐19 | 187 | Retrospective | Inflammation, direct viral damage, endothelial dysfunction, hypoxaemia | Increased risk of myocardial damage |

| Klok et al., 2020 52 | COVID‐19 | 184 | Retrospective | Inflammation, hypercoagulation, hypoxaemia | Increased risk of thrombotic complications |

| Wang et al., 2020 12 | COVID‐19 | 138 | Retrospective | Inflammation, hypoxaemia, viral damage | Increased risk of myocardial damage and arrhythmia |

| Varga et al., 2020 43 | COVID‐19 | 3 | Post‐mortem | Inflammation, vasoconstriction, direct viral damage | Endotheliitis, endothelial virus inclusion, myocardial ischaemia |

| Xu et al., 2020 38 | COVID‐19 | 1 | Post‐mortem | Inflammation | Cardiac interstitial inflammatory infiltrates |

AF, atrial fibrillation; CAD, coronary artery disease; CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; LV, left ventricular; MI, myocardial infarction; SARS‐CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

A second series of mechanisms are those related with the peculiar abnormal inflammatory response that COVID‐19 may elicit. Approximately 7 to 10 days after COVID‐19 onset, a hyper‐inflammatory response with massive cytokine release (cytokine storm) may occur. Such a response is likely the main cause of COVID‐19 pneumonia and ARDS and may be the cause of acute HF as well as other complications such as thromboembolic events, renal failure, shock and multiorgan failure. 20 , 21 , 24 , 25 , 53 The increased mortality of COVID‐19 patients with HF might also be explained by this mechanism as inflammatory activation and oxidative stress are present in these patients and may predispose them to a more severe clinical course once infected. 54 , 55

COVID‐19 is associated with a depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes caused by an immune reaction and/or by direct viral infection, with a predominance of neutrophils and innate immune macrophages. Ineffective activation of cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes and natural killer T lymphocytes favours virus persistence with further aspecific macrophage activation and massive cytokine release. This condition is similar to that described in oncology with immune targeted chimeric antigen receptor T‐cell therapies and in haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis syndromes. 7 , 41 , 53 , 56 Inflammation may take place in the endothelium. Biopsies and post‐mortem histological findings showed lymphocytic endotheliitis with apoptotic bodies and viral inclusion structures in multiple organs, including the lungs, heart, kidneys, gut. 38 , 43 Marked inflammation with endotheliitis can also lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation with small or large vessel thrombosis and infarction. 57

Consistent with this inflammatory hypothesis of COVID‐19, a persistent increase in inflammatory markers, such as C‐reactive protein, D‐dimer, ferritin, interleukin‐6, is associated with major complications and increased mortality. 20 , 21 , 24 A positive correlation was also noted between the increase in inflammatory markers and myocardial damage, consistent with the role of hyperinflammation as a cause of cardiac dysfunction. 24 , 25 Lastly, anti‐inflammatory therapies are currently studied for COVID‐19. 41 , 56 , 58 However, also drugs active on endothelial function, such as statins and ACEi or ARBs may be beneficial. 43

The role of angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2

SARS‐CoV attaches human cells after binding with its spikes to ACE2, a peptide highly expressed on the surface of lung alveolar epithelial cells, arterial and venous endothelial cells, arterial smooth muscle cells and enterocytes of the small intestine. 4 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 The spike glycoprotein S on the virion surface is cleaved into S1 and S2, forming a receptor domain capable of binding to ACE2 in the S1 subunit. 59 SARS‐CoV has a prominent cardiotropism. Autopsy reports of patients died from SARS showed viral RNA in the cardiac muscle in 35% of cases. The presence of SARS‐CoV in the heart was associated with marked reduction in ACE2 protein expression. 63

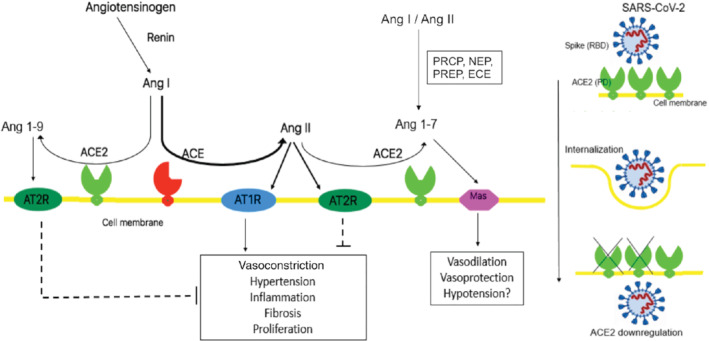

The binding domains of SARS‐CoV and SARS‐CoV‐2 are almost identical. However, the SARS‐CoV‐2 binding site is more compact and stable with enhanced affinity for ACE2 and has a furin cleavage site that can further increase its ability to infect cells. 7 , 64 Once binding is complete, the virus attaches ACE2 throughout membrane fusion and invagination, causing a down‐regulation in ACE2 activity 59 (Figure 2). The down‐regulation of ACE2 may be the result of ADAM‐17/TACE activation by SARS spike protein, which is known to cleave and release ACE2, and/or to the endocytosis of the ligand/receptor complex and subsequent intracellular degradation. 65 , 66

Figure 2.

Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). ACE2 is involved in the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system pathway but it is also a functional receptor for SARS‐CoV‐2. Ang I, angiotensin I; Ang II, angiotensin II; AT1R, angiotensin II type 1 receptor; AT2R, angiotensin II type 2 receptor; ECE, endothelin‐converting enzyme; NEP, neutral endopeptidase; PCRP, prolycarboxypeptidase; PREP, prolylendopeptidase; RBD, receptor binding domain; PD, peptidase domain.

ACE2 is an enzyme involved in the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system pathway. It has a catalytic domain 42% identical to ACE. 67 Despite this similarity, ACE2 cannot convert angiotensin I into angiotensin II and its catalytic efficiency is much higher towards angiotensin II. ACE2 cleaves angiotensin II, converting it into the heptapeptide angiotensin 1–7, which binds to Mas receptors that, opposite to angiotensin type 1 receptors, have vasodilatory, anti‐fibrotic and anti‐hypertrophic effects. 68 Of note, angiotensin 1–7 can also be synthesized by alternative pathways. ACE2 also has a weaker affinity for angiotensin I and can convert it into the nonapeptide angiotensin 1–9, limiting angiotensin II synthesis by ACE, and with vasodilatory effects through angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation (Figure 2).

Thus, ACE2 can counteract the untoward effects of angiotensin II with vasodilatory, anti‐inflammatory, antioxidant and antifibrotic effects. 68 , 69 , 70 In experimental models, ACE2 knockout mice were more likely to develop left ventricular systolic dysfunction and HF with reduced ejection fraction. 63 Overexpression of the ACE2 gene resulted in a more favourable post‐myocardial infarction remodelling and recovery. 71 ACE2 may have a role also for HF with preserved ejection fraction. ACE2 gene overexpression improved left ventricular diastolic function in experimental models through a reduction in reactive oxidative stress, fibrosis, myocardial hypertrophy. 72 , 73 Interestingly, ACE2 has also immunomodulatory properties both direct, through its interaction with macrophages, and indirect reducing angiotensin II which favours inflammation. 7 , 74

Myocardial injury, angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 and COVID‐19

In the heart, ACE2 is localized on the surface of coronary endothelial cells, cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts. ACE2 may have opposite effects in COVID‐19. First, it is up‐regulated in patients with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and/or treated with ACEi or ARB. 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 This has been shown in experimental models, 75 , 77 tissue samples from the myocardium of patients with end‐stage HF, 76 , 79 and using assays of ACE2 plasma levels. 78 , 80 A first study, where circulating levels of ACE2 were measured in a large European population of 1485 men and 537 women with HF and results were validated in another, independent cohort, has been recently published. 80 Plasma levels of ACE2 were increased in patients with HF and, interestingly, their strongest predictor was male sex in both cohorts, consistently with the increased prevalence and severity of COVID‐19 in males. 9 , 18 , 23 , 80 ACE2 up‐regulation may thus increase the susceptibility to COVID‐19 and favour a more severe clinical course of the illness through a larger viral burden into the cells. According to this hypothesis, which, however, remains to be proven, concerns regarding the administration of ACEi/ARBs, as a cause of ACE2 up‐regulation, were expressed. 81 , 83 , 84 , 85

Second, ACE2 is down‐regulated by SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and this may potentiate angiotensin II release and favour angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor stimulation, because of the loss of its counter‐regulatory effects. Thus, ACE2 may have a protective role, and heightened angiotensin II activity secondary to its down‐regulation may be a major mechanism leading to cardiac and/or lung injury, ARDS and other COVID‐19 complications. 83 , 85 , 86 According to this second hypothesis, ARBs may have protective effects with respect of COVID‐19 related organ damage.

COVID‐19 and angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker treatment

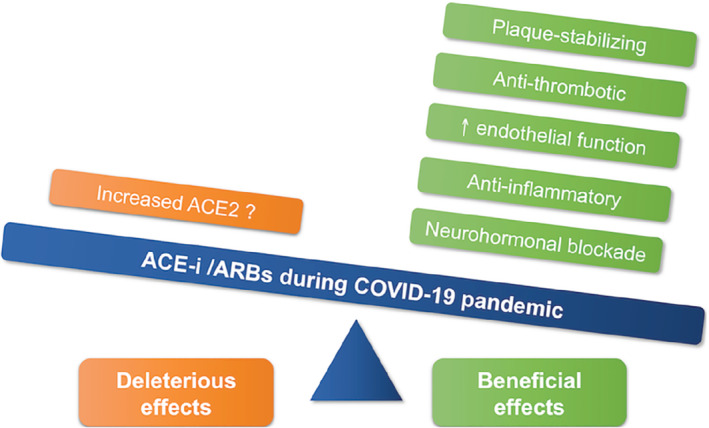

Based on what stated above, treatment with ACEi/ARBs may either be considered as harmful, as it may increase susceptibility to COVID‐19, or protective, as it may counteract increased AT1 receptor stimulation favoured by the loss of the counter‐regulatory effects of the down‐regulated ACE2. Mechanisms associated with potentially favourable or untoward effects of ACEi/ARBs in COVID‐19 patients are reported in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Deleterious and beneficial effects of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE‐i) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in COVID‐19 patients. ACE2, angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2.

Data from observational studies regarding plasma ACE2 levels and ACEi/ARB treatment in patients with COVID‐19 suggest at least a neutral role of ACEi/ARB treatment. In two large cohorts of patients with HF (index cohort: 2022 patients, validation cohort: 1698 patients), circulating ACE2 levels were increased in HF patients but the use of ACEi or ARBs had no relation with them in the index cohort and was associated with lower ACE2 levels in the validation cohort, suggesting a protective effect of these drugs. 80

Other studies regard the relation between ACEi/ARB treatment and the severity of COVID‐19. In a retrospective, single‐centre case series including 362 patients with hypertension hospitalized with COVID‐19, no difference in infection severity and mortality was found between patients who were receiving ACEi/ARBs and the others. 87 A larger series of 1128 hypertensive patients with COVID‐19 from a retrospective, multi‐centre study from nine hospitals in Hubei, China, showed a lower mortality in patients receiving ACEi/ARBs vs. the others (3.7% vs. 9.8%; P = 0.01). This difference remained significant after adjustment for risk factors and baseline variables at multivariable analysis and propensity analysis (adjusted hazard ratio 0.42; 95% confidence interval 0.19–0.92; P = 0.03, for ACEi/ARBs vs. non‐ACEi/ARBs). 88

Similar results came from non‐Chinese series. A population‐based case‐control study from the Lombardy region of Italy compared 6272 patients with COVID‐19 with 30 759 control subjects. Use of ACEi/ARBs was more frequent among patients with COVID‐19 than among controls because of their higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease. However, it was not an independent predictor of COVID‐19 or its severity. 27

Ongoing trials testing ACEi/ARB use/discontinuation in COVID‐19 are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ongoing trials testing angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker use/discontinuation in COVID‐19

| NCT number | Study title | Status | Study type | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04353596 | Stopping ACE‐inhibitors in COVID‐19 (ACEI‐COVID) | Recruiting | Interventional | Austria |

| NCT04351581 | Effects of Discontinuing Renin–angiotensin System Inhibitors in Patients With COVID‐19 (RASCOVID‐19) | Recruiting | Interventional | Denmark |

| NCT04345406 | Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors in Treatment of Covid 19 | Not yet recruiting | Interventional | Egypt |

| NCT04338009 | Elimination or Prolongation of ACE Inhibitors and ARB in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (REPLACECOVID) | Recruiting | Interventional | USA |

| NCT04337190 | Impact of Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers Treatment in Patients With COVID 19 (COVID‐ARA2) | Recruiting | Observational | France |

| NCT04335786 | Valsartan for Prevention of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Hospitalized Patients With SARS‐COV‐2 (COVID‐19) Infection Disease | Recruiting | Interventional | Netherlands |

| NCT04335123 | Study of Open Label Losartan in COVID‐19 | Recruiting | Interventional | USA |

| NCT04331574 | Renin–Angiotensin System Inhibitors and COVID‐19 (SARS‐RAS) | Recruiting | Observational | Italy |

| NCT04330300 | Coronavirus (COVID‐19) ACEi/ARB Investigation (CORONACION) | Recruiting | Interventional | Ireland |

| NCT04329195 | ACE Inhibitors or ARBs Discontinuation in Context of SARS‐CoV‐2 Pandemic (ACORES‐2) | Recruiting | Interventional | France |

| NCT04322786 | The Use of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Incident Respiratory Infections, Are They Harmful or Protective? | Active, not recruiting | Observational | UK |

| NCT04318418 | ACE Inhibitors, Angiotensin II Type‐I Receptor Blockers and Severity of COVID‐19 (COVID‐ACE) | Not yet recruiting | Observational | Italy |

| NCT04312009 | Losartan for Patients With COVID‐19 Requiring Hospitalization | Recruiting | Interventional | USA |

Conclusions and practical implications

A few conclusions can be drawn at this stage. First, we have shown the high prevalence of cardiac injury following COVID‐19 and this may be diagnosed only through biomarker measurements. This may become indicated in all patients hospitalized for COVID‐19 as independent prognostic markers. The clinical implications of the detection of myocardial injury remain, however, uncertain. No specific treatment is available. Agents with favourable effects on endothelial function may be tested in clinical trials.

A second aspect regards the role of ACEi/ARB treatment. No data have shown an increased COVID‐19 susceptibility or severity in patients receiving these agents. Therefore, these agents should not be discontinued during the COVID‐19 pandemic. In addition, as they may have a protective role for angiotensin II‐mediated organ damage during COVID‐19, they should also be tested in clinical trials to improve the still dramatic patients' clinical course.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1. Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses . The species severe acute respiratory syndrome‐related coronavirus: classifying 2019‐nCoV and naming it SARS‐CoV‐2. Nat Microbiol 2020;5:536–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, Wang W, Song H, Huang B, Zhu N, Bi Y, Ma X, Zhan F, Wang L, Hu T, Zhou H, Hu Z, Zhou W, Zhao L, Chen J, Meng Y, Wang J, Lin Y, Yuan J, Xie Z, Ma J, Liu WJ, Wang D, Xu W, Holmes EC, Gao GF, Wu G, Chen W, Shi W, Tan W. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 2020;395:565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang CL, Chen HD, Chen J, Luo Y, Guo H, Jiang RD, Liu MQ, Chen Y, Shen XR, Wang X, Zheng XS, Zhao K, Chen QJ, Deng F, Liu LL, Yan B, Zhan FX, Wang YY, Xiao GF, Shi ZL. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020;579:270–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X. COVID‐19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020;17:259–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Madjid M, Safavi‐Naeini P, Solomon SD, Vardeny O. Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: a review. JAMA Cardiol 2020. Mar 27. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, Sayer G, Griffin JM, Masoumi A, Jain SS, Burkhoff D, Kumaraiah D, Rabbani L, Schwartz A, Uriel N. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2020;141:1648–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu PP, Blet A, Smyth D, Li H. The science underlying COVID‐19: implications for the cardiovascular system. Circulation 2020;142:68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xiong TY, Redwood S, Prendergast B, Chen M. Coronaviruses and the cardiovascular system: acute and long‐term implications. Eur Heart J 2020;41:1798–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, Huang H, Zhang L, Zhou X, Du C, Zhang Y, Song J, Wang S, Chao Y, Yang Z, Xu J, Zhou X, Chen D, Xiong W, Xu L, Zhou F, Jiang J, Bai C, Zheng J, Song Y. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, Pu K, Chen Z, Guo Q, Ji R, Wang H, Wang Y, Zhou Y. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in coronavirus disease 2019 patients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2020;94:91–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, Lokhandwala S, Riedo FX, Chong M, Lee M. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID‐19 in Washington State. JAMA 2020;323:1612–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020;323:1061–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, Kim M, Jerome KR, Nalla AK, Greninger AL, Pipavath S, Wurfel MM, Evans L, Kritek PM, West TE, Luks A, Gerbino A, Dale CR, Goldman JD, O'Mahony S, Mikacenic C. Covid‐19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region – case series. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2012–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu K, Fang YY, Deng Y, Liu W, Wang MF, Ma JP, Xiao W, Wang YN, Zhong MH, Li CH, Li GC, Liu HG. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133:1025–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang JJ, Dong X, Cao YY, Yuan YD, Yang YB, Yan YQ, Akdis CA, Gao YD. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy 2020;75:1730–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mo P, Xing Y, Xiao Y, Deng L, Zhao Q, Wang H, Xiong Y, Cheng Z, Gao S, Liang K, Luo M, Chen T, Song S, Ma Z, Chen X, Zheng R, Cao Q, Wang F, Zhang Y. Clinical characteristics of refractory COVID‐19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis 2020. Mar 16. 10.1093/cid/ciaa270 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Inciardi RM, Adamo M, Lupi L, Cani DS, Di Pasquale M, Tomasoni D, Italia L, Zaccone G, Tedino C, Fabbricatore D, Curnis A, Faggiano P, Gorga E, Lombardi CM, Milesi G, Vizzardi E, Volpini M, Nodari S, Specchia C, Maroldi R, Bezzi M, Metra M. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID‐19 and cardiac disease in Northern Italy. Eur Heart J 2020;41:1821–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DS, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid‐19 . Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1708–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, Wu Y, Zhang L, Yu Z, Fang M, Yu T, Wang Y, Pan S, Zou X, Yuan S, Shang Y. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single‐centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:475–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reynolds HR, Adhikari S, Pulgarin C, Troxel AB, Iturrate E, Johnson SB, Hausvater A, Newman JD, Berger JS, Bangalore S, Katz SD, Fishman GI, Kunichoff D, Chen Y, Ogedegbe G, Hochman JS. Renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of Covid‐19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2441–2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020;323:1239–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, Cai Y, Liu T, Yang F, Gong W, Liu X, Liang J, Zhao Q, Huang H, Yang B, Huang C. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol 2020. Mar 25. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T, Wang H, Wan J, Wang X, Lu Z. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). JAMA Cardiol 2020. Mar 27. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G, Ma K, Xu D, Yu H, Wang H, Wang T, Guo W, Chen J, Ding C, Zhang X, Huang J, Han M, Li S, Luo X, Zhao J, Ning Q. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ 2020;368:m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mancia G, Rea F, Ludergnani M, Apolone G, Corrao G. Renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system blockers and the risk of Covid‐19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2431–2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wei JF, Huang FY, Xiong TY, Liu Q, Chen H, Wang H, Huang H, Luo YC, Zhou X, Liu ZY, Peng Y, Xu YN, Wang B, Yang YY, Liang ZA, Lei XZ, Ge Y, Yang M, Zhang L, Zeng MQ, Yu H, Liu K, Jia YH, Prendergast BD, Li WM, Chen M. Acute myocardial injury is common in patients with covid‐19 and impairs their prognosis. Heart 2020. Apr 30. 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317007 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lippi G, Lavie CJ, Sanchis‐Gomar F. Cardiac troponin I in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): evidence from a meta‐analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2020. Mar 10. 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.03.001 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dong N, Cai J, Zhou Y, Liu J, Li F. End‐stage heart failure with COVID‐19: strong evidence of myocardial injury by 2019‐nCoV. JACC Heart Fail 2020;8:515–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, Italia L, Raffo M, Tomasoni D, Cani DS, Cerini M, Farina D, Gavazzi E, Maroldi R, Adamo M, Ammirati E, Sinagra G, Lombardi CM, Metra M. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). JAMA Cardiol 2020. Mar 27. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tavazzi G, Pellegrini C, Maurelli M, Belliato M, Sciutti F, Bottazzi A, Sepe PA, Resasco T, Camporotondo R, Bruno R, Baldanti F, Paolucci S, Pelenghi S, Iotti GA, Mojoli F, Arbustini E. Myocardial localization of coronavirus in COVID‐19 cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:911–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zeng JH, Liu YX, Yuan J, Wang FX, Wu WB, Li JX, Wang LF, Gao H, Wang Y, Dong CF, Li YJ, Xie XJ, Feng C, Liu L. First case of COVID‐19 complicated with fulminant myocarditis: a case report and insights. Infection 2020. Apr 10. 10.1007/s15010-020-01424-5 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yu CM, Wong RS, Wu EB, Kong SL, Wong J, Yip GW, Soo YO, Chiu ML, Chan YS, Hui D, Lee N, Wu A, Leung CB, Sung JJ. Cardiovascular complications of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Postgrad Med J 2006;82:140–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alexander LK, Small JD, Edwards S, Baric RS. An experimental model for dilated cardiomyopathy after rabbit coronavirus infection. J Infect Dis 1992;166:978–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim IC, Kim JY, Kim HA, Han S. COVID‐19‐related myocarditis in a 21‐year‐old female patient. Eur Heart J 2020;41:1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sala S, Peretto G, Gramegna M, Palmisano A, Villatore A, Vignale D, De Cobelli F, Tresoldi M, Cappelletti AM, Basso C, Godino C, Esposito A. Acute myocarditis presenting as a reverse Tako‐Tsubo syndrome in a patient with SARS‐CoV‐2 respiratory infection. Eur Heart J 2020;41:1861–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C, Liu S, Zhao P, Liu H, Zhu L, Tai Y, Bai C, Gao T, Song J, Xia P, Dong J, Zhao J, Wang FS. Pathological findings of COVID‐19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:420–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhou R. Does SARS‐CoV‐2 cause viral myocarditis in COVID‐19 patients? Eur Heart J 2020;41:2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Peretto G, Sala S, Caforio AL. Acute myocardial injury, MINOCA, or myocarditis? Improving characterization of coronavirus‐associated myocardial involvement. Eur Heart J 2020;41:2124–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guzik TJ, Mohiddin SA, Dimarco A, Patel V, Savvatis K, Marelli‐Berg FM, Madhur MS, Tomaszewski M, Maffia P, D'Acquisto F, Nicklin SA, Marian AJ, Nosalski R, Murray EC, Guzik B, Berry C, Touyz RM, Kreutz R, Wang DW, Bhella D, Sagliocco O, Crea F, Thomson EC, McInnes IB. COVID‐19 and the cardiovascular system: implications for risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options. Cardiovasc Res 2020. Apr 30. 10.1093/cvr/cvaa106 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Farcas GA, Poutanen SM, Mazzulli T, Willey BM, Butany J, Asa SL, Faure P, Akhavan P, Low DE, Kain KC. Fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome is associated with multiorgan involvement by coronavirus. J Infect Dis 2005;191:193–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, Mehra MR, Schuepbach RA, Ruschitzka F, Moch H. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID‐19. Lancet 2020;395:1417–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen L, Li X, Chen M, Feng Y, Xiong C. The ACE2 expression in human heart indicates new potential mechanism of heart injury among patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2. Cardiovasc Res 2020;116:1097–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Madjid M, Miller CC, Zarubaev VV, Marinich IG, Kiselev OI, Lobzin YV, Filippov AE, Casscells SW 3rd. Influenza epidemics and acute respiratory disease activity are associated with a surge in autopsy‐confirmed coronary heart disease death: results from 8 years of autopsies in 34,892 subjects. Eur Heart J 2007;28:1205–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Corrales‐Medina VF, Alvarez KN, Weissfeld LA, Angus DC, Chirinos JA, Chang CC, Newman A, Loehr L, Folsom AR, Elkind MS, Lyles MF, Kronmal RA, Yende S. Association between hospitalization for pneumonia and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA 2015;313:264–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Violi F, Cangemi R, Falcone M, Taliani G, Pieralli F, Vannucchi V, Nozzoli C, Venditti M, Chirinos JA, Corrales‐Medina VF; SIXTUS (Thrombosis‐Related Extrapulmonary Outcomes in Pneumonia) Study Group . Cardiovascular complications and short‐term mortality risk in community‐acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2017;64:1486–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Milbrandt EB, Reade MC, Lee M, Shook SL, Angus DC, Kong L, Carter M, Yealy DM, Kellum JA; GenIMS Investigators . Prevalence and significance of coagulation abnormalities in community‐acquired pneumonia. Mol Med 2009;15:438–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Violi F, Carnevale R, Calvieri C, Nocella C, Falcone M, Farcomeni A, Taliani G, Cangemi R; SIXTUS Study Group . Nox2 up‐regulation is associated with an enhanced risk of atrial fibrillation in patients with pneumonia. Thorax 2015;70:961–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li SS, Cheng CW, Fu CL, Chan YH, Lee MP, Chan JW, Yiu SF. Left ventricular performance in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: a 30‐day echocardiographic follow‐up study. Circulation 2003;108:1798–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Takasu O, Gaut JP, Watanabe E, To K, Fagley RE, Sato B, Jarman S, Efimov IR, Janks DL, Srivastava A, Bhayani SB, Drewry A, Swanson PE, Hotchkiss RS. Mechanisms of cardiac and renal dysfunction in patients dying of sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:509–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJ, Arbous MS, Gommers D, Kant KM, Kaptein FH, van Paassen J, Stals MA, Huisman MV, Endeman H. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID‐19. Thromb Res 2020;191:145–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ; HLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK . COVID‐19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 2020;395:1033–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Markousis‐Mavrogenis G, Tromp J, Ouwerkerk W, Devalaraja M, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Dickstein K, Filippatos GS, van der Harst P, Lang CC, Metra M, Ng LL, Ponikowski P, Samani NJ, Zannad F, Zwinderman AH, Hillege HL, van Veldhuisen DJ, Kakkar R, Voors AA, van der Meer P. The clinical significance of interleukin‐6 in heart failure: results from the BIOSTAT‐CHF study. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. van der Pol A, van Gilst WH, Voors AA, van der Meer P. Treating oxidative stress in heart failure: past, present and future. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:425–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Agarwal S, June CH. Harnessing CAR T‐cell insights to develop treatments for hyperinflammatory responses in patients with COVID‐19. Cancer Discov 2020;10:775–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hendren NS, Drazner MH, Bozkurt B, Cooper LT Jr. Description and proposed management of the acute COVID‐19 cardiovascular syndrome. Circulation 2020;141:1903–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Feldmann M, Maini RN, Woody JN, Holgate ST, Winter G, Rowland M, Richards D, Hussell T. Trials of anti‐tumour necrosis factor therapy for COVID‐19 are urgently needed. Lancet 2020;395:1407–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS‐CoV‐2 by full‐length human ACE2. Science 2020;367:1444–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis ML, Lely AT, Navis G, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol 2004;203:631–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vaduganathan M, Vardeny O, Michel T, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD. Renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with Covid‐19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1653–1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hoffmann M, Kleine‐Weber H, Schroeder S, Kruger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, Muller MA, Drosten C, Pohlmann S. SARS‐CoV‐2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020;181:271–280.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Oudit GY, Kassiri Z, Jiang C, Liu PP, Poutanen SM, Penninger JM, Butany J. SARS‐coronavirus modulation of myocardial ACE2 expression and inflammation in patients with SARS. Eur J Clin Invest 2009;39:618–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Shang J, Ye G, Shi K, Wan Y, Luo C, Aihara H, Geng Q, Auerbach A, Li F. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS‐CoV‐2. Nature 2020;581:221–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Haga S, Yamamoto N, Nakai‐Murakami C, Osawa Y, Tokunaga K, Sata T, Yamamoto N, Sasazuki T, Ishizaka Y. Modulation of TNF‐alpha‐converting enzyme by the spike protein of SARS‐CoV and ACE2 induces TNF‐alpha production and facilitates viral entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:7809–7814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wang S, Guo F, Liu K, Wang H, Rao S, Yang P, Jiang C. Endocytosis of the receptor‐binding domain of SARS‐CoV spike protein together with virus receptor ACE2. Virus Res 2008;136:8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Donoghue M, Hsieh F, Baronas E, Godbout K, Gosselin M, Stagliano N, Donovan M, Woolf B, Robison K, Jeyaseelan R, Breitbart RE, Acton S. A novel angiotensin‐converting enzyme‐related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1‐9. Circ Res 2000;87:E1–E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Patel VB, Zhong JC, Grant MB, Oudit GY. Role of the ACE2/angiotensin 1‐7 axis of the renin‐angiotensin system in heart failure. Circ Res 2016;118:1313–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Simoes E Silva AC, Teixeira MM. ACE inhibition, ACE2 and angiotensin‐(1‐7) axis in kidney and cardiac inflammation and fibrosis. Pharmacol Res 2016;107:154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. South AM, Diz DI, Chappell MC. COVID‐19, ACE2, and the cardiovascular consequences. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2020;318:H1084–H1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Crackower MA, Sarao R, Oudit GY, Yagil C, Kozieradzki I, Scanga SE, Oliveira‐dos‐Santos AJ, da Costa J, Zhang L, Pei Y, Scholey J, Ferrario CM, Manoukian AS, Chappell MC, Backx PH, Yagil Y, Penninger JM. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature 2002;417:822–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Huentelman MJ, Grobe JL, Vazquez J, Stewart JM, Mecca AP, Katovich MJ, Ferrario CM, Raizada MK. Protection from angiotensin II‐induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis by systemic lentiviral delivery of ACE2 in rats. Exp Physiol 2005;90:783–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zhong J, Basu R, Guo D, Chow FL, Byrns S, Schuster M, Loibner H, Wang XH, Penninger JM, Kassiri Z, Oudit GY. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 suppresses pathological hypertrophy, myocardial fibrosis, and cardiac dysfunction. Circulation 2010;122:717–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Thomas MC, Pickering RJ, Tsorotes D, Koitka A, Sheehy K, Bernardi S, Toffoli B, Nguyen‐Huu TP, Head GA, Fu Y, Chin‐Dusting J, Cooper ME, Tikellis C. Genetic Ace2 deficiency accentuates vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis in the ApoE knockout mouse. Circ Res 2010;107:888–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, Averill DB, Brosnihan KB, Tallant EA, Diz DI, Gallagher PE. Effect of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2. Circulation 2005;111:2605–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zisman LS, Keller RS, Weaver B, Lin Q, Speth R, Bristow MR, Canver CC. Increased angiotensin‐(1‐7)‐forming activity in failing human heart ventricles: evidence for upregulation of the angiotensin‐converting enzyme Homologue ACE2. Circulation 2003;108:1707–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ishiyama Y, Gallagher PE, Averill DB, Tallant EA, Brosnihan KB, Ferrario CM. Upregulation of angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 after myocardial infarction by blockade of angiotensin II receptors. Hypertension 2004;43:970–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Epelman S, Tang WH, Chen SY, Van Lente F, Francis GS, Sen S. Detection of soluble angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 in heart failure: insights into the endogenous counter‐regulatory pathway of the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:750–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ohtsuki M, Morimoto SI, Izawa H, Ismail TF, Ishibashi‐Ueda H, Kato Y, Horii T, Isomura T, Suma H, Nomura M, Hishida H, Kurahashi H, Ozaki Y. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 gene expression increased compensatory for left ventricular remodeling in patients with end‐stage heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2010;145:333–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sama IE, Ravera A, Santema BT, van Goor H, ter Maaten JM, Cleland JG, Rienstra M, Friedrich AW, Samani NJ, Ng LL, Dickstein K, Lang CC, Filippatos G, Anker SD, Ponikowski P, Metra M, van Veldhuisen DJ, Voors AA. Circulating plasma concentrations of angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 in men and women with heart failure and effects of renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone inhibitors. Eur Heart J 2020;41:1810–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID‐19 infection? Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Aronson JK, Ferner RE. Drugs and the renin‐angiotensin system in covid‐19. BMJ 2020;369:m1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Guo J, Huang Z, Lin L, Lv J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and cardiovascular disease: a viewpoint on the potential influence of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers on onset and severity of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e016219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Sommerstein R, Kochen MM, Messerli FH, Grani C. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): do angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers have a biphasic effect? J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e016509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S, Huan Y, Guo F, Guan B, Yang P, Sarao R, Wada T, Leong‐Poi H, Crackower MA, Fukamizu A, Hui CC, Hein L, Uhlig S, Slutsky AS, Jiang C, Penninger JM. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature 2005;436:112–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Raiden S, Nahmod K, Nahmod V, Semeniuk G, Pereira Y, Alvarez C, Giordano M, Geffner JR. Nonpeptide antagonists of AT1 receptor for angiotensin II delay the onset of acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002;303:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Li J, Wang X, Chen J, Zhang H, Deng A. Association of renin‐angiotensin system inhibitors with severity or risk of death in patients with hypertension hospitalized for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) infection in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol 2020. Apr 23. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1624 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Zhang P, Zhu L, Cai J, Lei F, Qin JJ, Xie J, Liu YM, Zhao YC, Huang X, Lin L, Xia M, Chen MM, Cheng X, Zhang X, Guo D, Peng Y, Ji YX, Chen J, She ZG, Wang Y, Xu Q, Tan R, Wang H, Lin J, Luo P, Fu S, Cai H, Ye P, Xiao B, Mao W, Liu L, Yan Y, Liu M, Chen M, Zhang XJ, Wang X, Touyz RM, Xia J, Zhang BH, Huang X, Yuan Y, Rohit L, Liu PP, Li H. Association of inpatient use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with mortality among patients with hypertension hospitalized with COVID‐19. Circ Res 2020;126:1671–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]