Abstract

Acute demyelinating inflammatory polyneuropathy (AIDP) is the most common type of Guillain‐Barré syndrome (GBS) in Europe, following several viral and bacterial infections. Data on AIDP‐patients associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 (coronavirus‐2) infection are scarce. We describe the case of a 54‐years‐old Caucasian female patient with typical clinical and electrophysiological manifestations of AIDP, who was reported positive with PCR for SARS‐CoV‐2, 3 weeks prior to onset of the neurological symptoms. She did not experience a preceding fever or respiratory symptoms, but a transient loss of smell and taste. At the admission to our neurological department, a progressive proximally pronounced paraparesis, areflexia, and sensory loss with tingling of all extremities were found, which began 10 days before. The modified Erasmus Giullain‐Barré Syndrome outcome score (mEGOS) was 3/9 at admission and 1/12 at day 7 of hospitalization. The electrophysiological assessment proved a segmental demyelinating polyneuropathy and cerebrospinal fluid examination showed an albuminocytologic dissociation. The neurological symptoms improved significantly during treatment with immunoglobulins. Our case draws attention to the occurrence of GBS also in patients with COVID‐19 (coronavirus disease 2019), who did not experience respiratory or general symptoms. It emphasizes that SARS‐CoV‐2 induces immunological processes, regardless from the lack of prodromic symptoms. However, it is likely that there is a connection between the severity of the respiratory syndrome and further neurological consequences.

Keywords: COVID‐19, Guillain‐Barré syndrome, SARS‐CoV2

1. BACKGROUND AND AIMS

There is an emerging evidence that SARS‐CoV‐2 (coronavirus‐2) infection could be associated with neurological complications, including febril seizures, headache, dizziness, myalgia, as well with encephalopathy, encephalitis, stroke, and acute peripheral nerve diseases.1, 2 Neurotropic characteristics of coronavirus have been described in humans. It enters the CNS through the olfactory bulb due to a nasal infection, causing inflammation and demyelination which may lead to transitory loss of smell and taste, occasionally without fever and typical respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms in infected patients. 1 According to Helms et al., 58 of 64 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) due to Covid‐19 (coronavirus disease 2019), had neurological symptoms caused by encephalopathy with agitation, confusion, dysexecutive syndrome, ataxia, and corticospinal tract signs. MRI of two patients showed single acute ischemic strokes. 2

Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP) is a common form of Guillain‐Barré syndrome (GBS) characterized by ascending flaccid symmetrical limb paralysis with areflexia, sensory symptoms and often involvement of the cranial nerves. Typical electrodiagnostic features include signs of segmental demyelination as temporal dispersion of the compound muscle action potentials (CMAP) and sensory potentials, prolonged distal motor latencies and reduced conduction velocity in the demyelinative range as well as conduction blocks and absent or prolonged F‐waves. 3

A few patients with demyelinating and axonal type of Guillain‐Barré syndrome have been reported recently, the onset of neurological symptoms occurred 5 to 10 days after the diagnosis of COVID‐19 with respiratory symptoms.4, 5, 6, 7, 8

2. CASE REPORT

The 54‐year‐old, Caucasian female patient with an uneventful medical history was admitted to our neurological department in April 2020 with an acute, proximally pronounced, moderate, symmetric paraparesis (Medical Research Council/MRC/scale was 3/5 proximal and 4/5 distal in the lower extremities). Areflexia, numbness, and tingling of all extremities were also found, with initial maintained gain ability. These symptoms began 3 weeks following a positive reverse‐transcriptase‐polymerase‐chain‐reaction (PCR) oropharyngeal test for COVID‐19 and were progressing already for 10 days at admission. The test was performed because of her contact to a coronavirus‐positive person. She did not experience fever, respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms, but reported about a transient loss of smell and taste 2 weeks before the GBS symptoms occurred. The modified Erasmus Guillain‐Barré Syndrome outcome score (mEGOS) was 3/9 at admission and 1/12 at day 7 of hospitalization pointing to a favorable outcome. The general physical examination was normal, she had no fever and a new PCR‐oropharyngeal test was negative. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) assessment showed an albuminocytologic dissociation with increased protein level (140 g/L) and normal cell count, immunoassay, and Lyme‐serology were negative. SARS‐Cov‐2 RNA was not tested in CSF. Standard laboratory tests (complete blood count, CRP, serum glucose, creatinin, sodium and potassium level, TSH, creatine kinase, and urine test) and special blood tests (Campylobacter jejuni serology, HbA1c, ANA, anti‐DNA, c‐ANCA, p‐ANCA, HIV, serum vitamin B12‐level, and serum protein electrophoresis) were also within the normal range. MRI of the cervical spine and the chest x‐ray examination did not show pathological findings.

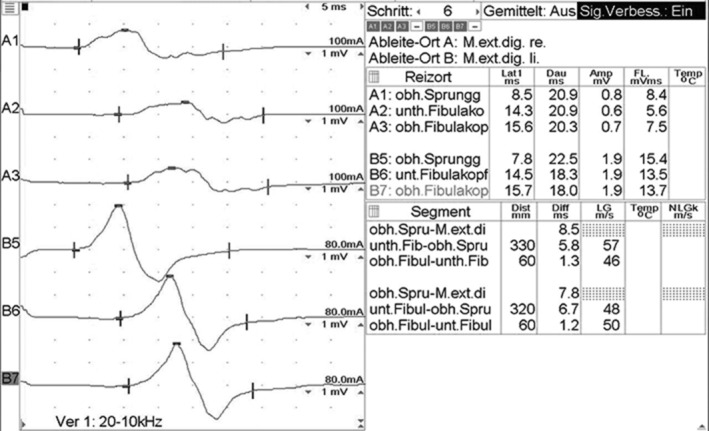

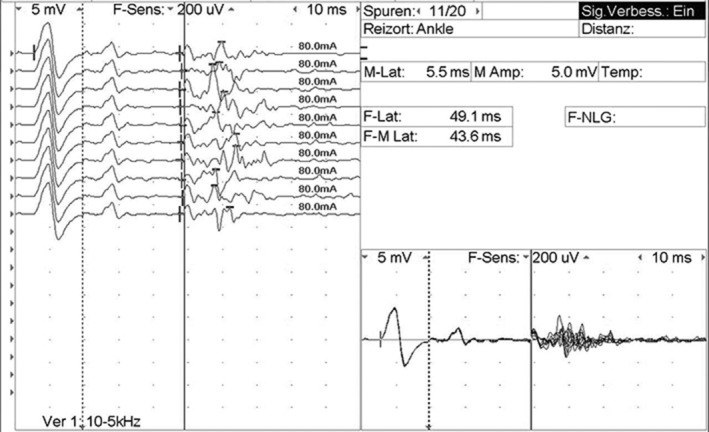

Electrophysiological studies were performed using a Nicolet Viking EMG device. The first electrophysiological evaluation (at admission) showed significantly prolonged distal motor latencies and temporal dispersion of the CMAP of the common peroneal nerve bilaterally (recorded from the extensor digitorum brevis muscle; Figure 1). Stimulation of the tibial nerves at the ankle elicited normal F‐wave latencies with pathological intermediate latency responses (complex A‐waves) on both sides (Figure 2). Motor nerve conduction studies of the tibial, median and ulnar nerves and sensory nerve conduction studies of the median, ulnar, and sural nerves were normal on both sides. Electromyography (EMG) showed no denervation signs. An acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy was diagnosed.

FIGURE 1.

Motor conduction study of the peroneal nerves with significantly prolonged distal motor latencies and temporal dispersion of CMAP‐s

FIGURE 2.

F‐wave study of the right tibial nerve with pathological intermediate‐latency response (A‐wave)

Two days after the admission the patient showed a deterioration of the paraparesis and complained about dysphagia. She received intravenous immunoglobulin at the dose of 0.4 g/kg/day given over the course of 5 days which was followed by an almost complete recovery. Follow‐up electrophysiological study was performed 14 days after admission, without significant changes in comparison to previous findings.

3. INTERPRETATION

Guillain‐Barré syndrome is caused by an aberrant autoimmune response to a preceding infection which evokes a cross‐reaction against gangliosid‐components of the peripheral nerves (“molecular mimicry”) targeting different antigens in the demyelinating and axonal subtypes of GBS. The most commonly identified precipitants are Campylobacter jejuni, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein‐Barr virus, influenza‐A virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae. Earlier discovered coronavirus‐types (SARS‐severe acute respiratory syndrome and MERS‐middle east respiratory syndrome) and Zika virus have been associated with GBS as well. 3

SARS‐CoV‐2 infection causes mostly fever and a severe respiratory syndrome, but other organ manifestations (heart, kidney, and gastrointestinal system) and neurological complications were also reported. The actual data indicate that SARS‐CoV‐2 is capable of causing an excessive immune reaction with an increased level of cytokines as Interleukin‐6 (IL‐6), which are produced by activated leukocytes and stimulate the inflammatory cascade leading to extensive tissue damage. IL‐6 plays an important role in multiple organ dysfunctions, which is often fatal for patients with COVID‐19.1, 2, 4, 5 It is likely, that these immunological processes are responsible for the major part of the organ manifestations, including the neurological complications. According to the literature it is likely that patients with severe symptoms of COVID‐19 and rapid clinical deterioration have more risk to develop serious neurological events.

Nine cases of GBS in patients with COVID‐19 have been recently reported.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 All patients had fever and respiratory symptoms 5 to 10 days before the onset of the neurological symptoms, one of them had ongoing fever and poor general condition. The electrodiagnostic findings were consistent with an axonal variant of GBS in four out of nine patients. In four other cases, a demyelinating subtype was found and in one patient the pathophysiology was not clear. All of them were treated with immunoglobulins. Toscano et al. 4 analyzed the data of five GBS‐patients with COVID‐19, admitted to three northern Italian hospitals. Three of them had a preceding anosmia or ageusia. Four patients still had a positive nasopharyngeal test for SARS‐CoV‐2 at the onset of the neurological symptoms. Antiganglioside antibodies were absent in the three patients who were tested for it. In all the cases, a real‐time polymerase‐chain‐reaction assay was negative for SARS‐CoV‐2 in CSF. Four of five patients had facial weakness and three of them developed respiratory failure in the course of the GBS, leading to a poor outcome. Four weeks after treatment, two patients remained in the intensive care unit and were receiving mechanical ventilation, two were undergoing physical therapy because of severe quadriparesis and only one could be discharged and was able to walk independently. Regarding to all nine reported patients in the literature, six had a respiratory failure and needed mechanical ventilation. It was not clear if the cause of the respiratory failure was the neuromuscular dysfunction due to GBS or the preceding severe respiratory infection. Furthermore, Gutiérrez et al. reported two cases of Miller‐Fisher syndrome in COVID‐19 patients, 3 to 5 days after onset of fever and general symptoms. Both patients had ageusia and one of them anosmia. PCR for coronavirus was positive in oropharyngeal sampling and negative in CSF in these cases. Both patients recovered completely. 9

The clinical and electrophysiological findings of our patient were consistent with AIDP, however, in contrast to the previously reported cases, she did not suffer from preceding fever or respiratory symptoms. Nevertheless, she did suffer from transient anosmia and ageusia. The clinical course of the GBS in this case was benign as well.

Seemingly, more serious respiratory symptoms in the acute phase of COVID‐19 are associated with a more severe form of GBS, as an indicator of the intensity of pathological immune response. On the other hand, the previous respiratory syndrome might aggravate the GBS‐symptoms leading to a worse outcome.

We conclude that GBS occurs also in patients with COVID‐19, who did not experience preceding respiratory symptoms or fever. Further studies should be conducted about the connection between early neurological symptoms as anosmia and ageusia and further neurological consequences of COVID‐19.

Scheidl E, Canseco DD, Hadji‐Naumov A, Bereznai B. Guillain‐Barré syndrome during SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic: A case report and review of recent literature. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2020;1–4. 10.1111/jns.12382

REFERENCES

- 1. Carod‐Artal FJ. Neurological complications of coronavirus and COVID‐19. Rev Neurol. 2020;70(9):311‐322. 10.33588/rn.7009.2020179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Helm J, Kremer S, Merdji H, et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. N Engl J Med. 2020; NEJMc2008597. 10.1056/NEJMc2008597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Willison HJ, Jacobs BC, van Doorn PA. Giullain‐Barre syndrome. Lancet. 2016;V338(10045):P717‐P727. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00339-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Toscano G, Palmerini F, Ravaglia S, et al. Guillain–Barré syndrome associated with SARS‐CoV‐2. N Engl J Med. 2020. 10.1056/NEJMc2009191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sedaghat Z, Karimi N. Guillain‐Barre syndrome associated with COVID‐19 infection: a case report. J Clin Neurosci. 2020. pii: S0967‐5868(20)30882‐1. 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.04.062 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Camdessanche J, Morel J, Pozzetto B, et al. COVID‐19 may induce Guillain‐Barré syndrome. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2020. 10.1016/j.neurol.2020.04.003 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Padroni M, Mastrangelo V, Asioli GM, et al. Guillain‐Barré syndrome following COVID‐19: new infection, old complication? J Neurol. 2020;24 10.1007/s00415-020-09849-6 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Virani A, Rabold E, Hanson T, et al. Guillain‐Barré syndrome associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. IDCases. 2020;20:e00771 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gutierrez‐Ortiz C, Mendez A, Rodrigo‐Rey S, et al. Miller‐Fisher syndrome and polyneuritis cranialis in COVID‐19. Neurology. 2020;pii:10.1212/WNL.0000000000009619. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009619 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]