Abstract

Background & aims

In the newly emerged Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) disaster, little is known about the nutritional risks for critically ill patients. It is also unknown whether the modified Nutrition Risk in the Critically ill (mNUTRIC) score is applicable for nutritional risk assessment in intensive care unit (ICU) COVID-19 patients. We set out to investigate the applicability of the mNUTRIC score for assessing nutritional risks and predicting outcomes for these critically ill COVID-19 patients.

Methods

This retrospective observational study was conducted in three ICUs which had been specially established and equipped for COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. The study population was critically ill COVID-19 patients who had been admitted to these ICUs between January 28 and February 21, 2020. Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) patients of <18 years; 2) patients who were pregnant; 3) length of ICU stay of <24 h; 4) insufficient medical information available. Patients' characteristics and clinical information were obtained from electronic medical and nursing records. The nutritional risk for each patient was assessed at their ICU admission using the mNUTRIC score. A score of ≥5 indicated high nutritional risk. Mortality was calculated according to patients’ outcomes following 28 days of hospitalization in ICU.

Results

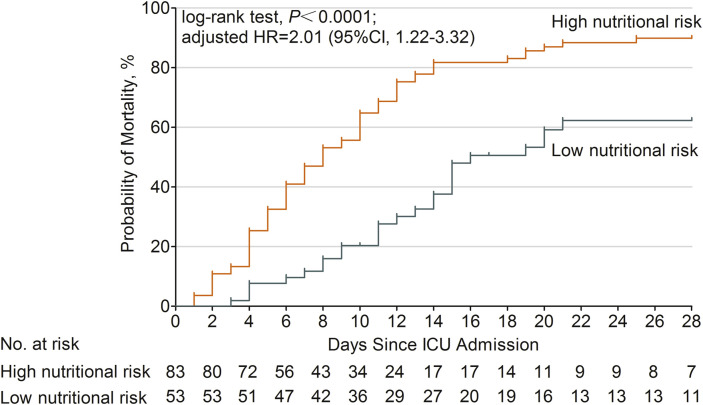

A total of 136 critically ill COVID-19 patients with a median age of 69 years (IQR: 57–77), 86 (63%) males and 50 (37%) females, were included in the study. Based on the mNUTRIC score at ICU admission, a high nutritional risk (≥5 points) was observed in 61% of the critically ill COVID-19 patients, while a low nutritional risk (<5 points) was observed in 39%. The mortality of ICU 28-day was significantly higher in the high nutritional risk group than in the low nutritional risk group (87% vs 49%, P <0.001). Patients in the high nutritional risk group exhibited significantly higher incidences of acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute myocardial injury, secondary infection, shock and use of vasopressors. Additionally, use of a multivariate Cox analysis showed that patients with high nutritional risk had a higher probability of death at ICU 28-day than those with low nutritional risk (adjusted HR = 2.01, 95% CI: 1.22–3.32, P = 0.006).

Conclusions

A large proportion of critically ill COVID-19 patients had a high nutritional risk, as revealed by their mNUTRIC score. Patients with high nutritional risk at ICU admission exhibited significantly higher mortality of ICU 28-day, as well as twice the probability of death at ICU 28-day than those with low nutritional risk. Therefore, the mNUTRIC score may be an appropriate tool for nutritional risk assessment and prognosis prediction for critically ill COVID-19 patients.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019, Modified NUTRIC score, Nutritional risk, Intensive care unit, 28-Day mortality

Abbreviations

- 2019-nCoV

2019 novel coronavirus

- APACHE II

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- ASPEN

American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- COVID-19

Coronavirus Disease 2019

- CRRT

continuous renal replacement therapy

- ECMO

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- EN

enteral nutrition

- ESPEN

European Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

- GCS

Glasgow coma scale

- HR

hazard ratio

- ICU

intensive care units

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- IQR

interquartile range

- LOS

length of stay

- MERS

Middle East respiratory syndrome

- mNUTRIC

modified Nutrition Risk in the Critically ill

- MV

mechanical ventilation

- NRS 2002

Nutritional Risk Screening 2002

- NUTRIC

Nutrition Risk in the Critically ill

- PN

parenteral nutrition

- SARS

severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- TPN

total parenteral nutrition

1. Introduction

Since December 2019, the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected more than 1,300,000 patients worldwide and caused more than 70,000 deaths. In the early stage of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak, one-third of the patients in Wuhan were admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) [1]. Reducing mortality in ICU is crucial in the treatment of COVID-19. Among the comprehensive treatment of critically ill COVID-19 patients, nutritional therapy must not be ignored. The nutritional status of each COVID-19 patient, particularly those in ICUs, should be evaluated before the administration of general treatments [2].

Nutritional risk is defined as the risk of adverse effects on clinical outcomes which are dependent on nutritional factors [3]. Patients who are at high nutritional risk should be recognized earlier during ICU stay, as such a risk is directly associated with adverse clinical outcomes [4]. Additionally, these patients could benefit more from nutritional interventions than those at lower nutritional risk [5]. Therefore, adequate assessment of nutritional risk should be a standard procedure for ICU patients.

The Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS 2002) score is a recommended tool for nutritional risk screening [3]. However, it was established based on data from general patients, rather than ICU populations. The Nutrition Risk in the Critically ill (NUTRIC) score, another recommended screening tool, was the first to be developed specifically for ICU patients [5,6]. In its newer, briefer version, the modified NUTRIC (mNUTRIC) score, the use of Interleukin-6 (IL-6) as a variable was excluded [7].

In the newly emerged COVID-19 disaster, little is known about the nutritional risks for critically ill COVID-19 patients. It is also unknown whether the mNUTRIC score is applicable for nutritional risk assessment for COVID-19 patients in the ICU. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective observational study in multiple COVID-19 specific ICUs in Wuhan, aiming to investigate the applicability of the mNUTRIC score for assessing nutritional risks and predicting outcomes for critically ill COVID-19 patients.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical considerations

This retrospective observational study was given approval by the Institutional Review Board of Tongji Hospital (Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China; No.TJ-IRB20200226). The clinical trial was registered and verified at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2000030816).

2.2. Study population and protocol

This retrospective observational study was conducted in three ICUs which had been specially established and equipped for COVID-19 in Tongji Hospital, affiliated to Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, China. The Chinese government has urgently assigned Tongji Hospital as a designated hospital for severely or critically ill COVID-19 patients. These ICUs were managed by three independent teams of intensivists, including one local team from Tongji Hospital and two teams of volunteers from Beijing and Shanghai. Full life support was provided for all the patients until cardiac death. Nutrition management plans were determined independently by the bedside team.

The study population was critically ill COVID-19 patients who had been admitted to one of the three ICUs between January 28 and February 21, 2020. All patients were diagnosed and classified according to the Guidance for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (6th edition), released by the National Health Commission of China [8].

Patients were excluded from the study if they were: 1) <18 years; 2) pregnant; 3) had a length of ICU stay <24 h; 4) had insufficient medical information.

2.3. Data collection

Patients' characteristics and clinical information were obtained from the hospital's electronic medical and nursing records. Trained reviewers validated and expanded the data using standardized data collection forms. The following data were retrieved: demographics; clinical and laboratory data; history; medical complications; main treatments; nutritional support pattern; and outcome.

Complications were defined as follow. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and shock were defined according to the interim clinical management guidance of World Health Organization for COVID-19 [9]. Acute myocardial injury was defined as serum levels of cardiac biomarkers (eg, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I) above the 99th percentile upper reference limit, or new abnormalities shown in electrocardiography and echocardiography [10]. Acute liver dysfunction was defined as elevated serum levels of alanine transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase and/or total bilirubin [11]. Acute kidney injury was defined according to the kidney disease improving global outcomes classification [12]. Secondary infection was defined as clinical symptoms or signs of nosocomial pneumonia or bacteremia and a positive culture of a new pathogen was obtained from lower respiratory tract specimens or blood samples after admission [13].

Each patient was evaluated according to the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation Ⅱ (APACHE Ⅱ) [14] and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) [15] scoring criteria within 24 h of their admission to the ICU. The nutritional risk for each patient was assessed at ICU admission using the mNUTRIC score. This score (0–9 points) was calculated based on the NUTRIC score by eliminating IL-6 values. It consisted of five variables: age, APACHE II score at admission, SOFA score at admission, number of comorbidities and pre-ICU hospital length of stay (LOS) [7]. A score of ≥5 indicated that a patient had a high nutritional risk. Mortality was calculated according to the patients’ outcomes at 28-day hospitalization in ICU.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Quantitative continuous variables were expressed as medians, with interquartile ranges (IQRs) compared using Mann–Whitney U tests. Qualitative and categorical variables were compared using Pearson χ2 test, continuity correction or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. A Kaplan–Meier curve was used to depict survival following 28 days in ICU and was stratified by nutritional risk according to the mNUTRIC score. Association of nutritional risk with ICU 28-day mortality risk was assessed using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses. Age, mean arterial pressure, white blood cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, platelets, prothrombin time, d-dimer, albumin, prealbumin, creatine kinase, urea, creatinine, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I, n-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide, procalcitonin and pH of arterial blood gas were adjusted in the multivariate Cox regression model. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 software (IBM Corp.) while GraphPad Prism version 4.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc.) was used to develop a Kaplan–Meier survival plot. All tests were two-sided. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the study population

A total of 136 critically ill COVID-19 patients, including 86 (63%) males and 50 (37%) females, were included in the study. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram. The study population was predominantly elderly, with a median age of 69 years (IQR: 57–77). Some 63% of patients were older than 65 years. One or more comorbidities were frequently seen, the most common of which were hypertension and diabetes (50% and 41%, respectively). Other comorbidities included cardiovascular disease, malignancy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, liver cirrhosis and immunopathy. Patients’ initial symptoms included fever, cough, dyspnea, diarrhea and hemoptysis. The median time from disease onset to ICU admission was 14 days (IQR: 10–18). At the time of ICU admission, patients had a median Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score of 13, a median APACHE II score of 18, and a median SOFA score of seven. During the ICU stay, patients developed several complications, including ARDS (88%), acute myocardial injury (54%), acute liver dysfunction (29%), acute kidney injury (41%), secondary infection (65%), shock (67%), embolization/thrombosis (2%) and pneumothorax (5%). Patients received oxygen therapy in different forms. A total of 51% of patients received noninvasive ventilation (bi-level), while 66% of patients received invasive mechanical ventilation (MV). The proportion of patients who were treated with vasopressors was high (66%). Other specific treatments also included continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT; 21%) and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO; 5%). The mortality of ICU 28-day was high (72%). Detailed characteristics of the study participants can be seen in Table 1 .

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 136 |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 69 (57–77) |

| ≥65 | 86 (63) |

| <65 | 50 (37) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 86 (63) |

| Female | 50 (37) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Hypertension | 68 (50) |

| Diabetes | 56 (41) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 26 (19) |

| Malignancy | 8 (6) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 12 (9) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5 (4) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 1 (1) |

| Immunopathy | 4 (3) |

| Initial symptoms | |

| Fever | 124 (91) |

| Cough | 104 (77) |

| Hemoptysis | 7 (5) |

| Dyspnea | 130 (96) |

| Diarrhea | 28 (21) |

| Time from disease onset to ICU admission, median (IQR), days | 14 (10–18) |

| GCS score, median (IQR) | 13 (8–15) |

| APACHE II score, median (IQR) | 18 (14–22) |

| SOFA score, median (IQR) | 7 (4–10) |

| Complications during ICU stay | |

| ARDS | 119 (88) |

| Acute myocardial injury | 74 (54) |

| Acute liver dysfunction | 40 (29) |

| Acute kidney injury | 56 (41) |

| Secondary infection | 88 (65) |

| Shock | 91 (67) |

| Embolization/Thrombosis | 3 (2) |

| Pneumothorax | 7 (5) |

| Treatments in ICU | |

| CRRT | 29 (21) |

| Vasopressors | 90 (66) |

| Oxygen therapy | |

| Nasal cannula | 26 (19) |

| Face mask with reservoir bag | 27 (20) |

| Noninvasive ventilation (bi-level) | 69 (51) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 90 (66) |

| Prone positioning | 20 (15) |

| ECMO | 7 (5) |

| Outcomes | |

| Death at ICU 28-day | 98 (72) |

Abbreviations: APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; ICU, intensive care units; IQR, interquartile range; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

3.2. Nutritional risk and outcomes

Based on mNUTRIC scores at ICU admission, a high nutritional risk (≥5 points) was observed in 61% of critically ill COVID-19 patients. A low nutritional risk (<5 points) was observed in 39%.

We divided the study population into high nutritional risk (mNUTRIC score ≥5 points) and low nutritional risk (mNUTRIC score <5 points) groups. Respective differences between these two groups were annotated and can be seen in Table 2 . The high nutritional risk group exhibited significantly greater incidences of ARDS, acute myocardial injury, secondary infection, shock and use of vasopressors. Finally, the mortality of ICU 28-day was significantly higher in the high nutritional risk group than in the low nutritional risk group (87% vs 49%, P <0.001).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical characteristics and initial laboratory indices among patients with high and low nutritional risk.

| Variable | Reference value | High nutritional risk group (mNUTRIC ≥5, n = 83), n (%) | Low nutritional risk group (mNUTRIC <5, n = 53), n (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age, median (IQR), years | 71 (63–80) | 64 (53–70) | <0.001 | |

| ≥65 | 60 (72) | 26 (49) | 0.006 | |

| <65 | 23 (28) | 27 (51) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 54 (65) | 32 (60) | 0.581 | |

| Female | 29 (35) | 21 (40) | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 41 (49) | 27 (51) | 0.860 | |

| Diabetes | 35 (42) | 21 (40) | 0.769 | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 16 (19) | 10 (19) | 0.953 | |

| Malignancy | 6 (7) | 2 (4) | 0.644 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 8 (10) | 4 (8) | 0.913 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5 (6) | 0 | 0.176 | |

| Liver cirrhosis | 0 | 1 (2) | 0.390 | |

| Immunopathy | 1 (1) | 3 (6) | 0.327 | |

| Initial symptoms | ||||

| Fever | 76 (92) | 48 (91) | 1.000 | |

| Cough | 60 (72) | 44 (83) | 0.150 | |

| Hemoptysis | 5 (6) | 2 (4) | 0.856 | |

| Dyspnea | 80 (96) | 50 (94) | 0.890 | |

| Diarrhea | 21 (25) | 7 (13) | 0.089 | |

| Vital signs, median (IQR) | ||||

| Heart rate, bpm | 102 (88–120) | 99 (84–110) | 0.314 | |

| Respiratory rate, bpm | 30 (25–35) | 30 (25–40) | 0.870 | |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 100 (86–107) | 104 (96–112) | 0.029 | |

| Laboratory indices at ICU admission, median (IQR) | ||||

| Blood routine | ||||

| White blood cells, × 109/L | 3.5–9.5 | 14.2 (9.8–19.0) | 9.2 (6.2–13.0) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophils, × 109/L | 1.8–6.3 | 12.7 (8.8–17.7) | 8.3 (5.3–11.4) | <0.001 |

| Lymphocytes, × 109/L | 1.1–3.2 | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.007 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 130–175 | 128 (115–140) | 129 (116–140) | 0.756 |

| Platelets, × 109/L | 125–350 | 116 (71–172) | 176 (133–24) | <0.001 |

| Coagulation function | ||||

| Prothrombin time, s | 12–15 | 17 (15–18) | 15 (14–17) | <0.001 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time, s | 29–42 | 38 (35–43) | 38 (35–41) | 0.184 |

| D-dimer, μg/mL | <0.5 | 21 (5–21) | 7 (2–21) | 0.008 |

| Blood biochemistry | ||||

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | ≤40 | 36 (25–63) | 31 (22–56) | 0.349 |

| Alanine transaminase, U/L | ≤41 | 28 (18–46) | 33 (22–49) | 0.196 |

| Total bilirubin, μmol/L | ≤26 | 15 (10–23) | 12 (8–16) | 0.002 |

| Albumin, g/L | 35–52 | 29 (25–32) | 30 (28–32) | 0.107 |

| Prealbumin, mg/L | 200–400 | 82 (80–122) | 95 (80–128) | 0.281 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 135–225 | 593 (405–835) | 495 (362–655) | 0.063 |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | ≤190 | 144 (73–342) | 143 (54–205) | 0.019 |

| Urea, mmol/L | 4–10 | 11 (8–18) | 7 (5–9) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 59–104 | 90 (65–144) | 67 (54–85) | <0.001 |

| High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I, pg/mL | ≤34 | 89 (25–619) | 14 (5–45) | <0.001 |

| N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide, pg/mL | <161 | 1235 (680–3717) | 376 (153–1445) | <0.001 |

| High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, mg/L | <1 | 118 (61–155) | 70 (43–127) | 0.005 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | 0.02–0.05 | 0.26 (0.20–0.87) | 0.24 (0.13–0.28) | 0.001 |

| Arterial blood gas | ||||

| pH | 7.35–7.45 | 7.38 (7.29–7.45) | 7.42 (7.36–7.47) | 0.009 |

| PaO2, mmHg | 80–100 | 58 (52–81) | 68 (55–79) | 0.161 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 35–45 | 42 (33–51) | 38 (34–43) | 0.139 |

| Time from disease onset to ICU admission, median (IQR), days | 14 (10–19) | 14 (10–16) | 0.263 | |

| GCS score, median (IQR), points | 12 (7–14) | 15 (14–15) | <0.001 | |

| APACHE II score, median (IQR), points | 21 (18–24) | 13 (9–16) | <0.001 | |

| SOFA score, median (IQR), points | 9 (7–11) | 4 (3–5) | <0.001 | |

| Complications during ICU stay | ||||

| ARDS | 81 (98) | 38 (72) | <0.001 | |

| Acute myocardial injury | 54 (65) | 20 (38) | 0.002 | |

| Acute liver dysfunction | 25 (30) | 15 (28) | 0.820 | |

| Acute kidney injury | 38 (46) | 18 (34) | 0.172 | |

| Secondary infection | 62 (75) | 26 (49) | 0.002 | |

| Shock | 65 (78) | 26 (49) | <0.001 | |

| Embolization/Thrombosis | 3 (4) | 0 | 0.281 | |

| Pneumothorax | 5 (6) | 2 (4) | 0.856 | |

| Treatments in ICU | ||||

| CRRT | 16 (19) | 13 (25) | 0.466 | |

| Vasopressors | 64 (77) | 26 (49) | 0.001 | |

| Oxygen therapy | ||||

| Nasal cannula | 7 (8) | 19 (36) | <0.001 | |

| Face mask with reservoir bag | 12 (15) | 15 (28) | 0.048 | |

| Noninvasive ventilation (bi-level) | 45 (54) | 24 (45) | 0.309 | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 60 (72) | 30 (57) | 0.059 | |

| Prone position | 10 (12) | 10 (19) | 0.273 | |

| ECMO | 5 (6) | 2 (4) | 0.856 | |

| Duration of noninvasive ventilation, median (IQR), days | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–3) | 0.865 | |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation, median (IQR), days | 5 (0–10) | 4 (0–11) | 0.323 | |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Death at ICU 28-day | 72 (87) | 26 (49) | <0.001 | |

Abbreviations: APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; ICU, intensive care units; IQR, interquartile range; mNUTRIC, modified Nutrition Risk in the Critically ill; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

The median survival time of patients in the high nutritional risk group was 8 days (95% confidence interval, CI: 6–10) and 16 days in the low nutritional risk group (95% CI: 12–20). Use of univariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis revealed a significantly higher mortality risk in the high nutritional risk group than the low nutritional risk group (hazard ratio, HR = 2.80, 95% CI: 1.78–4.40, P <0.001). Use of univariate Cox analysis also found elevated urea (increasing by one unit) as a risk factor of ICU 28-day mortality (HR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.03–1.07, P <0.001), while elevated prealbumin (increasing by one unit) was found to be a protective factor (HR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.989–0.999, P = 0.029). Further, use of multivariate Cox analysis demonstrated that patients with a high nutritional risk had a higher probability of death at ICU 28-day (adjusted HR = 2.01, 95% CI: 1.22–3.32, P = 0.006; Fig. 2 ). In this multivariate model, elevated urea remained a risk factor (HR = 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01–1.06, P = 0.005), and elevated prealbumin remained a protective factor (HR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.989–0.998, P = 0.011) of ICU 28-day mortality.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative probability of mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients with high and low nutritional risk. Patients with high nutritional risk (mNUTRIC score ≥5 points) had a higher probability of death at ICU 28-day than those with low nutritional risk (mNUTRIC score <5 points) (adjusted HR = 2.01, 95% CI: 1.22–3.32, P = 0.006).

We compared the scoring details of each item in the mNUTRIC score among survivals and non-survivals at ICU 28-day, which can be seen in Table 3 . We observed significant distribution differences between the two groups in the items of age, APACHE II score, SOFA score and comorbidities. Compared to the survivals, the non-survivals were significantly older, had higher APACHE II and SOFA scores and more comorbidities. Finally, the non-survival group exhibited significantly higher mNUTRIC score comparing to the survival group. However, we did not observe significant difference of pre-ICU hospital LOS in the two groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of each item in mNUTRIC score among survivals and non-survivals.

| Item | Score | Survivals (n = 38), n (%) | Non-survivals (n = 98), n (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age categories, years | ||||

| <50 | 0 | 9 (24) | 2 (2) | <0.001 |

| 50-<75 | 1 | 22 (58) | 63 (64) | |

| ≥75 | 2 | 7 (18) | 33 (34) | |

| APACHE II score categories, points | ||||

| <15 | 0 | 23 (61) | 17 (17) | <0.001 |

| 15-<20 | 1 | 10 (26) | 32 (33) | |

| 20-28 | 2 | 5 (13) | 38 (39) | |

| ≥28 | 3 | 0 | 11 (11) | |

| SOFA score categories, points | ||||

| <6 | 0 | 26 (68) | 24 (25) | <0.001 |

| 6-<10 | 1 | 9 (24) | 40 (41) | |

| ≥10 | 2 | 3 (8) | 34 (35) | |

| Comorbidities score categories | ||||

| 0-1 | 0 | 15 (40) | 18 (18) | 0.010 |

| ≥2 | 1 | 23 (61) | 80 (82) | |

| LOS in hospital before ICU admission categories, days | ||||

| 0-<1 | 0 | 14 (37) | 23 (24) | 0.116 |

| ≥1 | 1 | 24 (63) | 75 (77) | |

| Total mNUTRIC score, median (IQR), points | 3 (2–5) | 5 (4–7) | <0.001 | |

Abbreviations: APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; ICU, intensive care units; IQR, interquartile range; LOS, length of stay; mNUTRIC, modified Nutrition Risk in the Critically ill; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

3.3. Nutritional status and support of critically ill COVID-19 patients

In this study population of 136 critically ill COVID-19 patients, the median level of albumin was 30 g/L (IQR: 27–32) at admission to the ICU. Among the patients, only 11% presented a typical albumin level (≥35 g/L), while 56% presented an albumin level of less than 30 g/L. Patients’ median prealbumin level was 86 mg/L (IQR: 80–128), while the median hemoglobin level was 128 g/L (IQR: 115–140).

During their stay in ICUs, most patients (57%) received enteral nutrition (EN). Some 10% received total parenteral nutrition (TPN), while 22% received EN plus PN. The remaining 11% did not receive any nutritional support as a result of contraindications. For patients receiving EN, the major feeding route was via nasogastric tube (75%). Some 47% received oral feeding, while only 2% were fed via a nasal jejunal tube. EN intolerance occurred in some patients. Vomiting or gastric retention occurred in 32%, while hyperglycemia occurred in 63%. Others included diarrhea (5%) and hypoglycemia (3%). Patients’ detailed nutritional status, respective risk and support can be seen in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Nutritional status, risk and support.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 136 |

| Nutritional status | |

| Hemoglobin, median (IQR), g/L | 128 (115–140) |

| Albumin, median (IQR), g/L | 30 (27–32) |

| ≥35 | 15 (11) |

| 30-35 | 45 (33) |

| <30 | 76 (56) |

| Prealbumin, median (IQR), mg/L | 86 (80–128) |

| mNUTRIC score | |

| High nutritional risk (≥5 points) | 83 (61) |

| Low nutritional risk (<5 points) | 53 (39) |

| Nutritional support | |

| EN | 78 (57) |

| TPN | 13 (10) |

| EN + PN | 30 (22) |

| No nutritional support | 15 (11) |

| Route of EN | |

| Oral | 51 (47) |

| Nasogastric tube | 81 (75) |

| Nasal jejunal tube | 2 (2) |

| EN intolerance | |

| Vomiting/gastric retention | 34 (32) |

| Diarrhea | 5 (5) |

| Ileus | 0 |

| Hyperglycemia | 68 (63) |

| Hypoglycemia | 3 (3) |

Abbreviations: EN, enteral nutrition; IQR, interquartile range; mNUTRIC, modified Nutrition Risk in the Critically ill; PN, parenteral nutrition; TPN, total parenteral nutrition.

4. Discussion

The nutritional risks and applicability of the mNUTRIC score for critically ill COVID-19 patients are largely unknown. In this study, we for the first time report that a large proportion of critically ill COVID-19 patients had a high nutritional risk (mNUTRIC score ≥5 points). Patients with high nutritional risk at ICU admission exhibited significantly higher mortality of ICU 28-day, as well as twice the probability of death at ICU 28-day than those with low nutritional risk. Our data suggest that the mNUTRIC score may be an appropriate tool for nutritional risk assessment and prognosis prediction for critically ill COVID-19 patients.

According to a recent report from the Chinese Centers for Disease Control, 14% of confirmed COVID-19 cases are classified as severe and 5% as critically ill [16]. While the overall mortality rate of COVID-19 (2%) [16] is much lower than that of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS; 10%) [17] or Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS; 37%) [18], COVID-19 has caused more death globally owning to its rapid transmission and general susceptibilities. Among the critical cases in China, the case-fatality rate was reported to be 49% [16]. In the current study population, mortality of ICU 28-day was extremely high (72%). This could be explained by the fact that patients admitted to Tongji Hospital were either severely or critically ill, based on the designations of the Chinese government, and that patients in the three ICUs were most critically ill among those patients. Additionally, at the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak, the shortage of medical resources in Wuhan may have contributed to the high mortality rate. Some patients were in an extremely critical condition before being transferred to Tongji Hospital. Authors of a recent study reported that advanced age (>60), male sex and comorbidities (particularly hypertension) are risk factors for serious condition and death from the 2019-nCoV infection [19]. This is in accordance with the characteristics of participants in this study. Early comprehensive evaluation along with high-quality supportive care are urgently needed for patients deemed to be at high risk.

We found that a great portion of critically ill COVID-19 patients were at high nutritional risk. According to the mNUTRIC score at ICU admission, 61% of critically ill COVID-19 patients presented as having a high nutritional risk. In contrast, Kalaiselvan and colleagues [20] reported 43% of mechanically ventilated patients as having a high nutritional risk (mNUTRIC score ≥5 points). Mendes et al. [21] reported that 49% of ICU patients were at high nutritional risk based on their mNUTRIC scores. Median levels of albumin and prealbumin in the current study participants were lower than typical levels, which might reflect a poor nutritional status at ICU admission. One explanation may be that these patients were critically ill, with many of them also having multiple organ dysfunction. This is backed up by the high median APACHE II (18 points) and SOFA (7 points) scores at ICU admission. Another reason may be the long period from COVID-19 onset to ICU admission (median: 14 days, IQR: 10–18). During this period, patients’ increased catabolism and poor nutritional intake, caused by the illness, made their nutritional status even worse.

Nutritional support is crucial for critically ill patients. EN may impact ICU patients’ outcomes, especially mechanically ventilated patients [22]. EN is the preferred route for nutritional support if patients have a functioning gut. Authors of guidelines have recommend early EN, supplying 20–25 kcal/kg per day during the acute phase of critical illness [6,23]. However, early initiation of EN may induce gastrointestinal intolerance and vomiting in 30–70% of ICU patients, as well as gut ischemia in critically ill patients with shock [24]. EN should be postponed in patients with shock until full resuscitation with hemodynamic stability is achieved, according to guidelines [6,23]. In our study, nearly 80% of participants received EN; either total EN (57%) or EN plus PN (22%). Approximately 10% of patients received TPN due to EN contraindications, for example, shock and gastrointestinal bleeding. Despite this, 11% of patients had no nutritional support due to hemodynamic instability or short length of ICU stay.

Gastric intolerance, including vomiting and gastric retention, as well as pathoglycemia were the most common complications during the course of EN. The high incidence of diabetes (41%) and stress associated with being in a critical condition contributed to the frequent occurrences of hyperglycemia. In the current population, the high proportion of positive pressure ventilation, prone positioning and use of vasopressors might aggravate gastric intolerance.

The importance of disease severity and inflammation has been well recognized when characterizing malnutrition [25]. Both NRS 2002 and NUTRIC scoring systems take into account not only nutritional status but also disease severity, as both of these systems integrate the APACHE Ⅱ score. Additionally, the NUTRIC scoring system includes the SOFA score, which can be used to determine levels of organ dysfunction and mortality risk in ICU patients [26]. Firstly recommended by the European Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ESPEN) as the preferred tool for nutritional risk screening, the NRS 2002 is intended to cover all possible patient categories in a hospital [3]. However, many of the criteria included in the NRS 2002 score, such as food intake and anthropometric data, are hard to obtain in critically ill patients due to MV and sedation [27].

Use of NUTRIC scoring system in ICUs was first proposed by Canadian researchers [5]. In 2016, the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) recommended both the NRS 2002 and the NUTRIC scores for assessing nutrition support in critically ill patients [6]. The mNUTRIC score is a fast, practical instrument which can be incorporated into the routine ICU care, including COVID-19 specialized ICUs. Since the variables in the system are objectively obtained from routine data in patients' medical records, the mNUTRIC score has the advantage of application for patients who are unable to respond verbally, as in MV. We didn't use body mass index (BMI) or other physical measurements, such as triceps skinfold thickness, for nutritional assessment in this study, as these data were missing in most medical records. Additionally, body weight and bicep circumference might be affected by patients' illness condition and treatments, such as water-sodium retention, edema and limb vein thrombus. Through the use of multivariate Cox analyses, the elevated prealbumin, one nutrition related indicator, was revealed to be an independent protective factor of ICU 28-day mortality risk.

Use of the NUTRIC score is not limited to nutritionists, as it can point out relevant clinical outcomes. The NUTRIC score of patients at the start of hospitalization in ICU has been shown to be associated with MV, clinical complications, hospitalization time and death [28]. Additionally, nutritional risk according to the NUTRIC score has been shown to be a risk factor associated with survival time in ICUs [29]. In our study of critically ill COVID-19 patients, when comparing two groups according to mNUTRIC score, the high nutritional risk group exhibited significantly higher mortality of ICU 28-day, higher incidences of ARDS, acute myocardial injury, secondary infection, shock and use of vasopressors, as well as shorter survival time than found in the low nutritional risk group. Additionally, as revealed by multivariate Cox analysis, high nutritional risk was an independent risk factor for ICU 28-day mortality. Critically ill COVID-19 patients with high nutritional risk at ICU admission had twice the probability of death at ICU 28-day than those with low nutritional risk. Therefore, early nutritional risk screening and appropriate nutritional support must be standard procedures for critically ill COVID-19 patients in ICUs.

Differ from the recommendation of ASPEN, the NRS 2002 and the NUTRIC scores are no longer currently recommended by ESPEN for ICU patients [30]. The NUTRIC score does not directly evaluate any nutritional parameter, and is more heavily weighted by the APACHE II and SOFA scores, which emphasize the severity of illness. Thus it is not surprising to observe the association between the high NUTRIC score and high mortality. A recent study reported that the NUTRIC score had the greatest prognostic ability among four assessment tools in predicting ICU and 60-day mortality but the correlation was not sustained after adjustment for potential confounding factors [31]. It is inconsistent with other studies [21,32], as well as ours, reporting significant correlation between 28-day mortality and the NUTRIC score even after adjusting for multivariable analyses. As there is no gold standard to define the malnourishment and nutritional risk in ICU patients, further development and investigation of acute critical illness specific nutritional assessment tools are still needed.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, while patients were from three independent COVID-19 specific ICUs, they were all based in the same hospital. Thus, selection bias may exist. Secondly, only 136 critically ill COVID-19 patients were included. Studies with larger sample sizes are needed in the future. Thirdly, we did not perform dynamic nutritional risk assessments, which may provide more information and clues for patient outcomes. Finally, the typical limitations inherent to retrospective observational studies apply to our statistical analyses. Randomized and controlled studies would be better placed to determine whether nutrition interventions can improve the outcomes of critically ill COVID-19 patients.

In summary, our study is the first to investigate the use of the mNUTRIC score for a particular population of critically ill COVID-19 patients. Based on the mNUTRIC score at ICU admission, a high nutritional risk (≥5 points) was observed in 61% of these patients. The high nutritional risk group demonstrated significantly higher mortality of ICU 28-day than the low nutritional risk group. Critically ill COVID-19 patients with high nutritional risk at ICU admission were twice as likely to die at ICU 28-day than those with low nutritional risk. Therefore, the mNUTRIC score may be an appropriate tool for nutritional risk assessment and prognosis prediction in critically ill COVID-19 patients.

Statement of authorship

Concept and design of study: PZ, YB.

Data acquisition and analysis: PZ, YB, ZH, GY, DP, YF, JL, YW.

Statistical analysis: YB, SL, JL, YW.

Wrote the manuscript: PZ, YB.

Coordinated the analysis and reviewed the manuscript: SL, ZH, GY, YF, DP.

Funding sources

This study was supported by the COVID-19 Rapid Response Research Project of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Grant No. 2020kfyXGYJ049), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (Grant No. 2019CFB107, 2018CFB115).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the included patients and their families, physicians, nurses, dieticians, and all staff.

References

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang L., Liu Y. Potential interventions for novel coronavirus in China: a systematic review. J Med Virol. 2020;92(5):479–490. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kondrup J., Allison S.P., Elia M., Vellas B., Plauth M. ESPEN guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clin Nutr. 2003;22(4):415–421. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(03)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberda C., Gramlich L., Jones N., Jeejeebhoy K., Day A.G., Dhaliwal R. The relationship between nutritional intake and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: results of an international multicenter observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(10):1728–1737. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1567-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heyland D.K., Dhaliwal R., Jiang X., Day A.G. Identifying critically ill patients who benefit the most from nutrition therapy: the development and initial validation of a novel risk assessment tool. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):R268. doi: 10.1186/cc10546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClave S.A., Taylor B.E., Martindale R.G., Warren M.M., Johnson D.R., Braunschweig C. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: society of critical care medicine (SCCM) and American society for parenteral and enteral nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2016;40(2):159–211. doi: 10.1177/0148607115621863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahman A., Hasan R.M., Agarwala R., Martin C., Day A.G., Heyland D.K. Identifying critically-ill patients who will benefit most from nutritional therapy: further validation of the "modified NUTRIC" nutritional risk assessment tool. Clin Nutr. 2016;35(1):158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Health Commission of China New coronavirus pneumonia prevention and control program (6th ed) http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/8334a8326dd94d329df351d7da8aefc2/files/b218cfeb1bc54639af227f922bf6b817.pdf (in Chinese) 2020. Available from:

- 9.World Health Organization . 2020. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection is suspected: interim Guidance.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330893 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao C., Wang Y., Gu X., Shen X., Zhou D., Zhou S. Association between cardiac injury and mortality in hospitalized patients infected with avian influenza A (H7N9) virus. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(4):451–458. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X., Fang X., Cai Z., Wu X., Gao X., Min J. Research (Wash D C); 2020. Comorbid chronic diseases and acute organ injuries are strongly correlated with disease severity and mortality among COVID-19 patients: a systemic Review and meta-analysis; p. 2402961. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120(4):c179–c184. doi: 10.1159/000339789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garner J.S., Jarvis W.R., Emori T.G., Horan T.C., Hughes J.M. CDC definitions for nosocomial infections, 1988. Am J Infect Contr. 1988;16(3):128–140. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(88)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knaus W.A., Draper E.A., Wagner D.P., Zimmerman J.E. Apache II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vincent J.L., Moreno R., Takala J., Willatts S., De Mendonca A., Bruining H. The SOFA (Sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on sepsis-related problems of the European society of intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(7):707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization . 2003. Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003.https://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2004_04_21/en/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) 2019. https://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ Available from:

- 19.Chen T., Wu D., Chen H., Yan W., Yang D., Chen G. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalaiselvan M.S., Renuka M.K., Arunkumar A.S. Use of nutrition risk in critically ill (NUTRIC) score to assess nutritional risk in mechanically ventilated patients: a prospective observational study. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2017;21(5):253–256. doi: 10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_24_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendes R., Policarpo S., Fortuna P., Alves M., Virella D., Heyland D.K. Nutritional risk assessment and cultural validation of the modified NUTRIC score in critically ill patients-A multicenter prospective cohort study. J Crit Care. 2017;37:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen K., Hoffman L. Enteral nutrition in the mechanically ventilated patient. Nutr Clin Pract. 2019;34(4):540–557. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kreymann K.G., Berger M.M., Deutz N.E., Hiesmayr M., Jolliet P., Kazandjiev G. ESPEN guidelines on enteral nutrition: intensive care. Clin Nutr. 2006;25(2):210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reignier J., Boisrame-Helms J., Brisard L., Lascarrou J.B., Ait Hssain A., Anguel N. Enteral versus parenteral early nutrition in ventilated adults with shock: a randomised, controlled, multicentre, open-label, parallel-group study (NUTRIREA-2) Lancet. 2018;391(10116):133–143. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White J.V., Guenter P., Jensen G., Malone A., Schofield M. Consensus statement: academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition) J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2012;36(3):275–283. doi: 10.1177/0148607112440285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medlej K. Calculated decisions: sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score. Emerg Med Pract. 2018;20(Suppl 10):CD1–CD2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Preiser J.C., van Zanten A.R., Berger M.M., Biolo G., Casaer M.P., Doig G.S. Metabolic and nutritional support of critically ill patients: consensus and controversies. Crit Care. 2015;19:35. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0737-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reis A.M.D., Fructhenicht A.V.G., Moreira L.F. NUTRIC score use around the world: a systematic review. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2019;31(3):379–385. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20190061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jose I.B., Leandro-Merhi V.A., Aquino J.L.B., Mendonca J.A. The diagnosis and NUTRIC score of critically ill patients in enteral nutrition are risk factors for the survival time in an intensive care unit? Nutr Hosp. 2019;36(5):1027–1036. doi: 10.20960/nh.02545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singer P., Blaser A.R., Berger M.M., Alhazzani W., Calder P.C., Casaer M.P. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(1):48–79. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rattanachaiwong S., Zribi B., Kagan I., Theilla M., Heching M., Singer P. Comparison of nutritional screening and diagnostic tools in diagnosis of severe malnutrition in critically ill patients. Clin Nutr. 2020 Nov;39(11):3419–3425. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mukhopadhyay A., Henry J., Ong V., Leong C.S., Teh A.L., van Dam R.M. Association of modified NUTRIC score with 28-day mortality in critically ill patients. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(4):1143–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]