Key Points

Question

What are the associations between noninvasive oxygenation strategies and outcomes among adults with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure?

Findings

In this systematic review and network meta-analysis that included 25 studies and 3804 patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, compared with standard oxygen therapy there was a statistically significant lower risk of death with helmet noninvasive ventilation (risk ratio, 0.40) and face mask noninvasive ventilation (risk ratio, 0.83).

Meaning

Noninvasive oxygenation strategies compared with standard oxygen therapy were significantly associated with lower risk of death.

Abstract

Importance

Treatment with noninvasive oxygenation strategies such as noninvasive ventilation and high-flow nasal oxygen may be more effective than standard oxygen therapy alone in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.

Objective

To compare the association of noninvasive oxygenation strategies with mortality and endotracheal intubation in adults with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.

Data Sources

The following bibliographic databases were searched from inception until April 2020: MEDLINE, Embase, PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, Web of Science, and LILACS. No limits were applied to language, publication year, sex, or race.

Study Selection

Randomized clinical trials enrolling adult participants with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure comparing high-flow nasal oxygen, face mask noninvasive ventilation, helmet noninvasive ventilation, or standard oxygen therapy.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two reviewers independently extracted individual study data and evaluated studies for risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. Network meta-analyses using a bayesian framework to derive risk ratios (RRs) and risk differences along with 95% credible intervals (CrIs) were conducted. GRADE methodology was used to rate the certainty in findings.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality up to 90 days. A secondary outcome was endotracheal intubation up to 30 days.

Results

Twenty-five randomized clinical trials (3804 participants) were included. Compared with standard oxygen, treatment with helmet noninvasive ventilation (RR, 0.40 [95% CrI, 0.24-0.63]; absolute risk difference, −0.19 [95% CrI, −0.37 to −0.09]; low certainty) and face mask noninvasive ventilation (RR, 0.83 [95% CrI, 0.68-0.99]; absolute risk difference, −0.06 [95% CrI, −0.15 to −0.01]; moderate certainty) were associated with a lower risk of mortality (21 studies [3370 patients]). Helmet noninvasive ventilation (RR, 0.26 [95% CrI, 0.14-0.46]; absolute risk difference, −0.32 [95% CrI, −0.60 to −0.16]; low certainty), face mask noninvasive ventilation (RR, 0.76 [95% CrI, 0.62-0.90]; absolute risk difference, −0.12 [95% CrI, −0.25 to −0.05]; moderate certainty) and high-flow nasal oxygen (RR, 0.76 [95% CrI, 0.55-0.99]; absolute risk difference, −0.11 [95% CrI, −0.27 to −0.01]; moderate certainty) were associated with lower risk of endotracheal intubation (25 studies [3804 patients]). The risk of bias due to lack of blinding for intubation was deemed high.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this network meta-analysis of trials of adult patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, treatment with noninvasive oxygenation strategies compared with standard oxygen therapy was associated with lower risk of death. Further research is needed to better understand the relative benefits of each strategy.

This network meta-analysis of randomized trials estimates association of use of noninvasive ventilation (high-flow nasal oxygen; face mask or helmet noninvasive ventilation) vs standard oxygen therapy with mortality and endotracheal intubation among adults with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.

Introduction

Acute hypoxemic respiratory failure is among the leading causes of intensive care unit admission in adult patients, often leading to endotracheal intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation.1 The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has further highlighted the importance of understanding the best approach to providing respiratory support for patients with respiratory failure. Invasive mechanical ventilation is associated with severe adverse events,2 and avoiding unnecessary endotracheal intubation remains a major goal in the management of patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.3 Multiple noninvasive oxygenation strategies have been developed to support oxygenation and ventilation that may lead to a reduced risk of endotracheal intubation and mortality. However, it remains unclear which of these is most effective.4

Standard oxygen therapy, typically at flow rates of less than 15 L/min, has been the conventional approach to delivering supplemental oxygen to patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Alternatively, noninvasive ventilation using either a face mask or helmet interface has been promoted to reduce the risk of endotracheal intubation. Oxygen delivery at high flow via nasal cannula has been gaining acceptance because of the ability to more closely match a patient’s inspiratory demand in the setting of hypoxemia.5 Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) comparing the effectiveness of noninvasive ventilation or high-flow nasal oxygen with standard oxygen therapy have produced conflicting results.6,7,8,9,10,11,12 Patients in the control groups in most of these trials received standard oxygen therapy, and there have been few head-to-head comparisons of the other different noninvasive oxygenation modalities.7,11 Moreover, most meta-analyses have been limited to traditional pairwise comparisons and therefore have not combined direct and indirect evidence for all potential comparisons.13,14,15,16

To provide additional clinical information, a network meta-analysis was conducted to compare the association of different noninvasive oxygenation strategies with mortality and receipt of endotracheal intubation in adult patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.

Methods

This review has been conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols statement extension for network meta-analysis.17,18 The protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42019121755) and has been published.19 No institutional review board approval was required because all study data had been published previously and this study did not include individual patient data.

Eligibility Criteria, Literature Search, and Study Selection

A systematic literature search was conducted through April 2020 to identify RCTs enrolling adult patients (>18 years of age) with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure comparing high-flow nasal oxygen, face mask noninvasive ventilation, helmet noninvasive ventilation, or standard oxygen therapy and evaluating 1 or both of the 2 key outcomes of mortality or endotracheal intubation. Studies that were primarily focused on the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ie, >50% of the study population) or congestive heart failure (ie, >50% of the study population) and those evaluating noninvasive oxygen strategies in the immediate postextubation period and after major cardiovascular surgery were excluded. The rationale for excluding studies primarily enrolling these patients was based on the established efficacy of noninvasive ventilation for these conditions.20,21 However, we anticipated that some included randomized studies would also include patients with congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, given that the etiology of acute respiratory failure is often unclear at presentation or may have an acute on chronic component.

The following electronic bibliographic databases were searched from inception until April 2020 using a comprehensive search strategy developed by an information specialist: Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, PubMed (non-MEDLINE records only), Ovid Evidence-Based Medicine Reviews–Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EBSCO CINAHL Complete, Web of Science, and LILACS. The search also included ClinicalTrials.gov, the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number Registry (ISRCTN) for all registered clinical trials and RCTs. The search strategy was structured according to the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) 2015 guidelines.22 A validated search filter for RCTs from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0, Section 6.4.11, was used to screen Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, and PubMed. A pretested search filter for RCTs from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network was used to screen CINAHL Complete and Web of Science. No limits were applied to language, sex, or race.

The full texts of all articles identified as relevant during the title and abstract screening stage were obtained and reviewed. The comprehensive search strategy and detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in eAppendix 1 in the Supplement.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality, measured at the longest time point reported in the first 90 days after randomization. The secondary outcome was endotracheal intubation, measured at the longest time point reported up to 30 days. Additional secondary outcomes included patient comfort, dyspnea scores, intensive care unit and hospital lengths of stay, and 6-month mortality.

Data Extraction, Risk of Bias, and GRADE Certainty Assessment

Two reviewers (B.L.F. and F.A.) independently extracted individual study data and evaluated studies for risk of bias using a previously piloted standardized form and the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for RCTs.23 The following domains of each of the primary studies were assessed: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of study participants, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases. Based on these domains, the overall risk of bias for each included study was assessed. The certainty of each direct, indirect, and network meta-analysis estimate was estimated based on the 4-step approach suggested by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group (ie, high, moderate, low, and very low certainty).24 In the presence of incoherence (ie, differences between direct and indirect evidence), the lower certainty of the 2 assessments was assigned to the corresponding network estimate.24

Statistical Analysis

A series of pairwise conventional meta-analyses were performed with random-effects models to assess for direct associations between interventions and study outcomes. Network meta-analyses using bayesian random-effects models (log-link, binomial likelihood) were conducted to derive head-to-head treatment estimates comparing all interventions. Analyses were based on Markov chain Monte Carlo methods using minimally informative treatment effect estimates and informative prior distributions for heterogeneity estimates, following the approach suggested by Turner et al.25

Although these prior distributions were derived in the log odds scale, it was expected that these would be wide enough to cover possible values in the log relative risk scale. Correction of the treatment associations for multigroup trials was applied.26 Further details on the model specification are in eAppendix 2 in the Supplement. Pairwise and network risk ratios (RRs) were derived, estimating summary estimates from the medians and corresponding 95% credible intervals (CrIs) from the 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles of the posterior distribution. In addition to relative associations, bayesian analyses were used to produce risk differences and 95% CrIs between treatment groups. Prior distributions for event rates of intubation and all-cause mortality in the standard oxygen therapy group were derived from the data and from previous literature.27 The probability for each treatment to obtain each possible rank (probability of being best, second best, etc) was also estimated.28 Specifically, in the bayesian framework and in each Markov chain Monte Carlo cycle, each treatment was ranked according to the estimated effect size. The proportion of cycles in which a treatment ranks first out of the total turns into the probability of being first, second, and so forth.29

Heterogeneity in treatment effects between studies was quantified using the posterior distribution τ2. Incoherence between direct and indirect comparisons was estimated using the node-splitting approach contrasting estimates from both direct and indirect evidence.30,31 Model convergence was assessed using the Brooks-Gelman-Rubin diagnostic, trace plots, and autocorrelation plots. Goodness of fit was assessed by comparing the mean residual deviance with the number of contributing data points. Statistical significance was defined as 95% CrIs that did not include the value 1.0. All analyses were performed in R version 3.6 (R Foundation; packages meta, gemtc, coda, pcnetmeta, and rjags) using Just Another Gibbs Sampler (JAGS) version 4.3.0 and OpenBUGS.

Sensitivity Analyses

Several sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of the pooled RRs for the main outcomes. These analyses excluded studies that enrolled any patient with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart failure, studies that enrolled postoperative patients, and studies that included patients with less severe respiratory failure (mean partial pressure of arterial oxygen [Pao2] to fraction of inspired oxygen [Fio2] ratio >200). Because there was variability in the timing of reporting of mortality, the analysis of the primary outcome was limited to studies that reported mortality at hospital discharge. An analysis restricted to studies that included at least 50% of immunocompromised patients (ie, >50% of patients with hematologic malignancies, solid tumors with active chemotherapy, treatment with immunosuppressant drugs, or solid organ transplants) was also conducted. Furthermore, to assess the effect of study quality, an analysis restricted to studies with the lowest risk of bias was performed. In addition, to assess the robustness of the findings, the main analyses were refitted using noninformative priors for heterogeneity and also using moderately enthusiastic priors for treatment effects for high-flow nasal oxygen and skeptical priors for face mask noninvasive ventilation, based on measures of association and distributions obtained from recent evidence.7,27,32 These latter sensitivity analyses were intended to account for a subgroup of clinicians who may have greater confidence in high-flow nasal oxygen compared with face mask noninvasive ventilation. Details are in eAppendix 2 in the Supplement. In addition, we performed post hoc sensitivity analyses to explore sources of incoherence when this was present.

Results

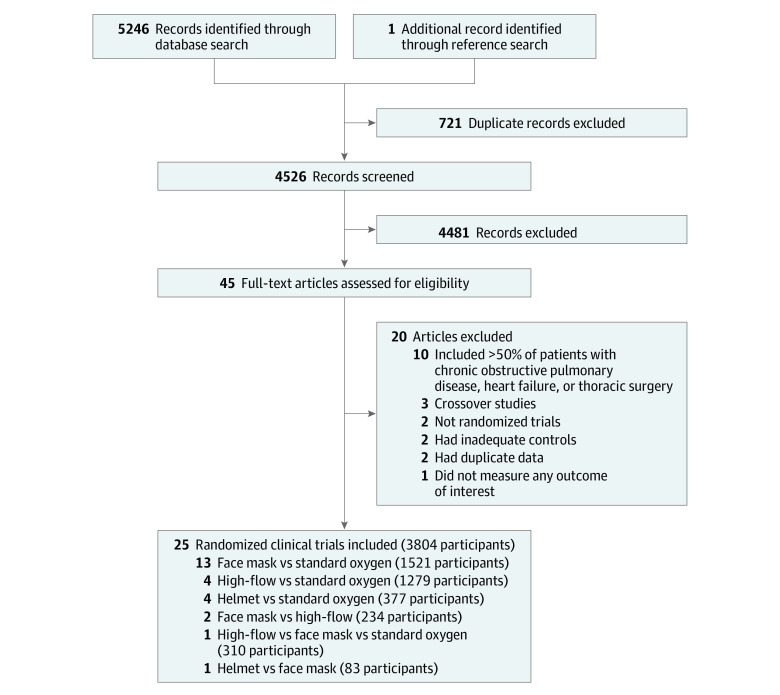

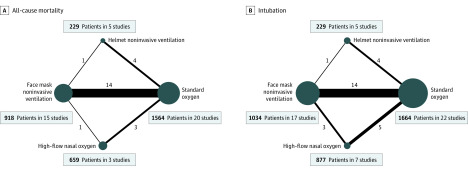

The search strategy identified 5246 records, including 25 RCTs (3804 participants; range, 30-776 participants) that were eligible for inclusion (Figure 1). Included trials evaluated 4 different interventions, and these included 5 of 6 potential head-to-head comparisons. Specifically, 13 trials compared face mask noninvasive ventilation with standard oxygen therapy, 4 trials compared high-flow nasal oxygen with standard oxygen therapy, 2 trials compared face mask noninvasive ventilation with high-flow nasal oxygen, 1 trial compared face mask with helmet noninvasive ventilation, and 4 trials compared helmet noninvasive ventilation with standard oxygen therapy (Table and Figure 2). In addition, a 3-group study directly compared face mask noninvasive ventilation with high-flow nasal oxygen and also with standard oxygen therapy (therefore, there were a total of 27 comparisons for 25 RCTs).7 No studies compared high-flow nasal oxygen with helmet noninvasive ventilation.

Figure 1. Summary of Study Retrieval and Identification for Network Meta-analysis.

Table. Main Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Source | Funding | Total No. of patients | Main reason for hypoxemic respiratory failure (main baseline risk factor) | Age, mean, y | Pao2:Fio2 ratio | Respiratory rate, /min | Main exposure | Comparator | Outcomes of interest assessed | Timing of measurement for study outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonelli et al,6 2000 | Undisclosed | 40 | Mixed ARF (immunocompromised [100%]) | 45 | 129 | 38 | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 20) | Standard oxygen (n = 20) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, hospital discharge |

| Azevedo et al,33 2015 | Undisclosed | 30 | CAP (CHF [43%]) | 67 | NA | NA | High-flow nasal oxygen (n = 14) | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 16) | Intubation | ICU discharge |

| Azoulay et al,34 2018 | French Ministry of Health | 776 | CAP (immunocompromised [100%]) | 64a | 132 | 33 | High-flow nasal oxygen (n = 388) | Standard oxygen (n = 388) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, hospital discharge, 28 days |

| Bell et al,35 2015 | Fisher & Paykel | 100 | Mixed ARF | 73 | NA | 33 | High-flow nasal oxygen (n = 48) | Standard oxygen (n = 52) | Intubation | Emergency department, ICU discharge |

| Brambilla et al,9 2014 | IRCCS Fondazione Ca’Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan | 81 | CAP (immunocompromised [32%]) | 67 | 141 | 34 | Helmet noninvasive ventilation (n = 40) | Standard oxygen (n = 41) | Death, intubation | Hospital discharge |

| Confalonieri et al,36 1999 | Undisclosed | 56 | CAP | 64 | 175 | 37 | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 28) | Standard oxygen (n = 28) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, 60 days |

| Cosentini et al,37 2010b | Undisclosed | 47 | CAP | 69 | 248 | 27 | Helmet noninvasive ventilation (n = 20) | Standard oxygen (n = 27) | Death, intubation | Emergency department |

| Delclaux et al,38 2000 | Vital Signs Inc | 123 | CAP | 58a | 144 | 33 | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 62) | Standard oxygen (n = 61) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, hospital discharge |

| Doshi et al,10 2018 | Vapotherm | 204 | Mixed ARF (acute exacerbation COPD [26%]) | 63 | NA | 30 | High-flow nasal oxygen (n = 104) | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 100) | Intubation | 72 hours |

| Ferrer et al,39 2003 | Red GIRA, Red Respira, and Carburos Metalicos SA | 105 | CAP (immunocompromised [20%]; CHF [28%]) | 62 | 103 | 37 | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 51) | Standard oxygen (n = 54) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge |

| Frat et al,7 2015 | French Ministry of Health | 310 | CAP (immunocompromised [26.5%]) | 60 | 155 | 33 | High-flow nasal oxygen (n = 106) | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 110); standard oxygen (n = 94) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, 90 days |

| Hernandez et al,40 2010 | Consejería de Sanidad de Castilla | 50 | Chest trauma | 43 | 109 | NA | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 25) | Standard oxygen (n = 25) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, hospital discharge |

| He et al,41 2019 | National Natural Science Foundation of China | 200 | CAP | 55 | 231 | 25 | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 102) | Standard oxygen (n = 98) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, hospital discharge |

| Hilbert et al,42 2001 | Undisclosed | 52 | CAP (immunocompromised [100%]) | 49 | 139 | 36 | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 26) | Standard oxygen (n = 26) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, hospital discharge |

| Jaber et al,43 2016 | Montpellier University Hospital and APARD Foundation | 293 | Mixed ARF (abdominal surgery [100%]; active cancer [50%]) | 64 | 195 | 29 | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 148) | Standard oxygen (n = 145) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, 30 days, 90 days |

| Jones et al,44 2016 | Greenlane Research and Education Fund | 303 | Mixed ARF (COPD [23.9%]; CHF [12.3%]) | 73 | NA | 33 | High-flow nasal oxygen (n = 165) | Standard oxygen (n = 138) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, hospital discharge, 90 days |

| Lemiale et al,8 2015 | Legs Poix (Chancellerie des Universités de Paris) and OUTCOMEREA Study Group | 374 | Pneumonia (immunocompromised [100%]) | 63a | 142 | 26 | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 191) | Standard oxygen (n = 183) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, 30 days, 180 days |

| Lemiale et al,45 2015 | Fisher & Paykel | 100 | Mixed ARF (immunocompromised [100%]) | 62a | 114 | 27 | High-flow nasal oxygen (n = 52) | Standard oxygen (n = 48) | Intubation | 2 hours |

| Martin et al,46 2000 | Undisclosed | 61 | Mixed ARF (COPD [38%]) | 61 | 199 | 28 | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 32) | Standard oxygen (n = 29) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge |

| Patel et al,11 2016 | National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute | 83 | CAP (immunocompromised [100%]) | 60a | 131 | 28 | Helmet noninvasive ventilation (n = 44) | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 39) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, hospital discharge |

| Squadrone et al,47 2005 | Università di Torino | 209 | Mixed ARF (abdominal surgery [100%]; solid organ transplant [14%]; cancer [62%]) | 66 | 251 | NA | Helmet noninvasive ventilation (n = 105) | Standard oxygen (n = 104) | Death, intubation | 7 days, ICU discharge, hospital discharge |

| Squadrone et al,48 2010 | Regione Piemonte (CEP AN RAN 07) and Ministero dell’Università (PRIN RANI 07) | 40 | Mixed ARF (hematologic malignancies [100%]) | 49 | 269 | 30 | Helmet noninvasive ventilation (n = 20) | Standard oxygen (n = 20) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, hospital discharge, 90 days |

| Wermke et al,49 2012 | Undisclosed | 86 | CAP (immunocompromised [100%]) | 52a | 270 | NA | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 42) | Standard oxygen (n = 44) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, 100 days |

| Wysocki et al,50 1995 | Undisclosed | 41 | CAP (CHF [30%]) | 63 | 207 | 35 | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 21) | Standard oxygen (n = 20) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge |

| Zhan et al,51 2012 | Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission Program | 40 | ALI (immunocompromised [30%]) | 46 | 230 | 20 | Face mask noninvasive ventilation (n = 21) | Standard oxygen (n = 19) | Death, intubation | ICU discharge, hospital discharge |

Abbreviations: ALI, acute lung injury; ARF, acute respiratory failure; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Fio2, fraction of inspired oxygen; ICU, intensive care unit; NA, not available; Pao2, partial pressure of arterial oxygen.

Age was reported as median.

No patients died or were intubated (ie, no events were available for analysis).

Figure 2. Network Plots for the Association of Noninvasive Oxygenation Strategies With All-Cause Mortality and Intubation.

Network geometry shows nodes as interventions and each head-to-head direct comparison as lines connecting these nodes. There is no direct comparison between high-flow nasal oxygen and helmet noninvasive ventilation for any of the study outcomes. The size of the nodes is proportional to the number of participants in each node. The thickness of the connecting line is proportional to the number of randomized clinical trials in each comparison. Both network plots include 1 study (n = 47) that did not report any event of death or intubation and 1 three-group study (face mask noninvasive ventilation, high-flow nasal oxygen, and standard oxygen therapy). Therefore, the total number of comparisons is higher than the number of randomized clinical trials for each outcome. Patients may be included in multiple comparisons, and this is accounted within the bayesian model and does not mean participants are duplicated.

The Table describes the main study and cohort characteristics of the included trials. Mean age at randomization ranged from 30 to 75 years, mean Pao2:Fio2 ratio was predominantly below 200 (14 trials [56%]), and more than half of the trials (14 trials [56%]) allowed inclusion of immunocompromised patients. Community-acquired pneumonia was the most common cause of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure in 16 trials (64%). Pairwise comparisons are shown in eFigure 1 in the Supplement.

Noninvasive Oxygenation Strategies and Risk of Mortality

Twenty-one trials (3370 patients) were included in the mortality analysis, of which 1 (47 patients) did not report any deaths in any of the treatment groups.37 Despite the absence of blinding, the risk of bias was determined to be low for the outcome of mortality in most (16 trials [76%]) of these trials (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

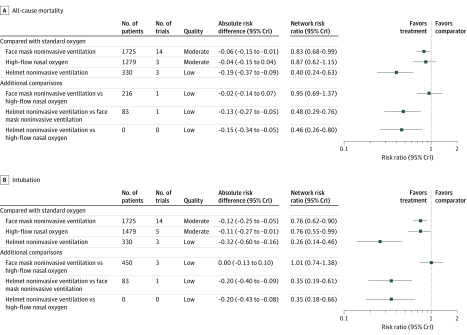

Using standard oxygen as the reference, helmet noninvasive ventilation (RR, 0.40 [95% CrI, 0.24-0.63]; absolute risk difference, −0.19 [95% CrI, −0.37 to −0.09]; low certainty) and face mask noninvasive ventilation (RR, 0.83 [95% CrI, 0.68-0.99]; absolute risk difference, −0.06 [95% CrI, −0.15 to −0.01]; moderate certainty) were significantly associated with a lower risk of mortality. High-flow nasal oxygen (RR, 0.87 [95% CrI, 0.62-1.15]; absolute risk difference, −0.04 [95% CrI, −0.15 to 0.04]; moderate certainty) was not associated with a statistically significant lower risk of mortality compared with standard oxygen therapy. Figure 3A and eFigure 2 in the Supplement show the results for all potential comparisons in the network meta-analysis for all-cause mortality. Helmet noninvasive ventilation was also associated with a significant decrease in mortality compared with high-flow nasal oxygen (RR, 0.46 [95% CrI, 0.26-0.80]; absolute risk difference, −0.15 [95% CrI, −0.34 to −0.05]; low certainty) and face mask noninvasive ventilation (RR, 0.48 [95% CrI, 0.29-0.76]; absolute risk difference, −0.13 [95% CrI, −0.27 to −0.05]; low certainty). There was no significant difference in the association with mortality when comparing face mask noninvasive ventilation with high-flow nasal oxygen (RR, 0.95 [95% CrI, 0.69-1.37]; absolute risk difference, −0.02 [95% CrI, −0.14 to −0.07]; low certainty). Incoherence between direct and indirect RRs was observed for the comparison of face mask noninvasive ventilation vs high-flow nasal oxygen (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). The probability of being best in reducing all-cause mortality among all possible interventions was higher for helmet noninvasive ventilation, followed by face mask noninvasive ventilation, high-flow nasal oxygen, and standard oxygen therapy (eFigure 4 in the Supplement). eTable 2 in the Supplement summarizes the evidence grading for all comparisons (direct, indirect, and network estimates) and for both study outcomes.

Figure 3. Forest Plots for the Association of Noninvasive Oxygenation Strategies With Study Outcomes.

A, For the primary outcome, all-cause mortality, the longest follow-up was up to 90 days. B, For the secondary outcome, intubation, the longest follow-up was up to 30 days. All outcomes are reported as network risk ratios and absolute risk differences with 95% credible intervals (CrIs). The certainty for each network meta-analysis estimate was estimated based on the 4-step approach suggested by the GRADE Working Group. Initially, each direct and indirect comparison was rated independently using the GRADE approach (risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision), and these were used to rate the network estimate. In case of disagreement between the direct and indirect rating, the network estimate was assigned the higher rating. In the presence of incoherence, the network estimate was assigned the lower rating of the direct/indirect assessment. For estimating risk ratios for the comparison of helmet noninvasive ventilation vs high-flow nasal cannula, only indirect evidence was used because no direct pairwise comparisons were available. The estimated absolute risk of mortality and endotracheal intubation was 30% and 40%, respectively, in the standard oxygen group. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed by using the posterior distribution for τ, τ2, and the I2 statistic. For all-cause mortality, τ = 0.17 (95% CrI, 0.056-0.23), τ2 = 0.0284 (95% Crl, 0.00317-0.0508), and I2 = 12%. For endotracheal intubation, τ = 0.21 (95% CrI, 0.07-0.27), τ2 = 0.0437 (95% Crl, 0.00554-0.0743), and I2 = 15%.

Noninvasive Oxygenation Strategies and Risk of Endotracheal Intubation

Twenty-five RCTs (3804 patients) were included in the analysis of endotracheal intubation, of which 1 RCT (47 patients) did not report any intubation events in any of the treatment groups.37 All studies were unblinded for this outcome, and the risk of bias for this outcome was assessed as high due to potential cointerventions and variable criteria for endotracheal intubation between groups. The overall risk of bias assessed across all domains was deemed to be high for 7 (28%) and unclear for 18 (72%) of the 25 trials included (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Helmet noninvasive ventilation (RR, 0.26 [95% CrI, 0.14-0.46]; absolute risk difference, −0.32 [95% CrI, −0.60 to −0.16]; low certainty), face mask noninvasive ventilation (RR, 0.76 [95% CrI, 0.62-0.90]; absolute risk difference, −0.12 [95% CrI, −0.25 to −0.05]; moderate certainty), and high-flow nasal oxygen (RR, 0.76 [95% CrI, 0.55-0.99]; absolute risk difference, −0.11 [95% CrI, −0.27 to −0.01]; moderate certainty) were associated with a lower risk of endotracheal intubation compared with standard oxygen therapy (Figure 3B and eFigure 5 in the Supplement). Helmet noninvasive ventilation was associated with decreased risk of endotracheal intubation compared with high-flow nasal (RR, 0.35 [95% CrI, 0.18-0.66]; absolute risk difference, −0.20 [95% CrI, −0.43 to −0.08]; low certainty) and face mask noninvasive ventilation (RR, 0.35 [95% CrI, 0.19-0.61]; absolute risk difference, −0.20 [95% CrI, −0.40 to −0.09]; low certainty). No significant difference was observed for the association with endotracheal intubation when comparing face mask noninvasive ventilation and high-flow nasal oxygen (RR, 1.01 [95% CrI, 0.74-1.38]; absolute risk difference, −0.00 [95% CrI, −0.13 to 0.10]; low certainty). There was incoherence between the direct and indirect RRs for the comparison of face mask noninvasive ventilation vs high-flow nasal oxygen (eFigure 6 in the Supplement). A post hoc sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the incoherence was eliminated when studies that included patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and congestive heart failure and the study by Frat et al7 were excluded (eFigure 7 in the Supplement). The probability of being best in reducing risk of endotracheal intubation was highest for helmet noninvasive ventilation, followed by face mask noninvasive ventilation, high-flow nasal oxygen, and standard oxygen therapy (eFigure 8 in the Supplement). Model fit and convergence characteristics are shown in eFigures 9 and 10 and eTable 4 in the Supplement.

Additional Secondary Outcomes

Median intensive care unit and hospital lengths of stay for different noninvasive strategies are presented in eTable 5 in the Supplement; no significant differences were evident between groups. Meaningful results for prespecified secondary outcomes of patient comfort (reported in only 28% of studies) and dyspnea score (reported in only 16% of studies) could not be generated because insufficient information for all network comparisons was available. In addition, 6-month mortality was available in only 1 study.8

Sensitivity Analyses

For the primary outcome, the observed association between face mask noninvasive ventilation and reduced risk of mortality was no longer significant when considering studies that included only patients with more severe respiratory failure (mean Pao2:Fio2 ratio <200), when using noninformative priors for heterogeneity, and after excluding studies that enrolled any patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, with congestive heart failure, or who were in the postoperative period (eTable 6 in the Supplement). However, the association of helmet ventilation with a lower risk of mortality remained significant across all sensitivity analyses. For the secondary outcome, all noninvasive ventilation strategies remained significantly associated with reduced risk of intubation across multiple sensitivity analyses when compared with standard oxygen therapy. Finally, the analyses restricted to studies with low risk of bias yielded results similar to the main analysis for all comparisons (eTables 6 and 7 in the Supplement).

The overall results were robust when the analyses considered moderately optimistic priors that high-flow nasal oxygen would be associated with benefit and skeptical priors that face mask ventilation would be associated with harm. In these analyses, helmet noninvasive ventilation remained associated with a lower risk of endotracheal intubation and all-cause mortality compared with standard oxygen therapy. However, face mask noninvasive ventilation was no longer associated with a lower risk of intubation compared with standard oxygen therapy (eTables 8 and 9 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this network meta-analysis of trials of adults with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, treatment with noninvasive oxygenation strategies compared with standard oxygenation therapy was associated with a lower risk of death, the primary outcome, and endotracheal intubation, a secondary outcome.

The results of this study exhibit the potential benefit of delivering noninvasive ventilation using a helmet interface to patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, although the low certainty should be considered when interpreting these results. These findings are consistent with a recent systematic review and traditional pairwise meta-analysis that showed that use of helmet noninvasive ventilation was associated with decreased risk of intubation and mortality compared with other modalities.13 However, in addition to not including indirect evidence, this previous study included both randomized and observational studies and included studies primary targeting patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The results of this network meta-analysis also raise the question of whether helmet noninvasive ventilation and face mask noninvasive ventilation should be considered distinct therapeutic interventions with potentially different physiological and clinical effects. Physiological studies have shown that the helmet interface decreases air leaks compared with the face mask interface; decreased air leaks may allow for more effective delivery of higher levels of positive end-expiratory pressure, potentially increasing alveolar recruitment and decreasing respiratory effort.3,52,53,54 Patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure may also have better tolerance for a helmet interface compared with other strategies, minimizing interruptions in therapy.11

The finding that face mask noninvasive ventilation was associated with a lower rate of overall mortality and endotracheal intubation when compared with standard oxygen therapy needs to be assessed in the context of the uncertainty existing in the literature and relatively small sample size of included studies. It is possible that this association is driven by inclusion of patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure who also have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and/or congestive heart failure; face mask noninvasive ventilation has been demonstrated to be helpful in these situations.21,55,56,57,58,59In the sensitivity analyses excluding trials that included such patients, the association with decreased mortality was no longer observed.

Concerns regarding the safety of face mask noninvasive ventilation for patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure have been raised based on associations with increased mortality in large observational studies in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome.27,60 Clinicians who believe that face mask noninvasive ventilation may be harmful for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure might consider the sensitivity analysis using skeptical priors, in which face mask ventilation was no longer associated with a lower risk of intubation and mortality when compared with standard oxygen therapy and might even be associated with increased harm when compared with high-flow nasal oxygen therapy. Potential mechanisms for such harm include higher-than-targeted tidal volumes while patients breathe spontaneously, leading to high transpulmonary pressures and patient self-inflicted lung injury.60,61 Although these potential harms might be especially important for face mask noninvasive ventilation, they may be common to all noninvasive oxygenation strategies, particularly by further delaying intubation and perpetuating lung injury in patients with high respiratory effort.61,62,63 This might be especially relevant for more severely ill patients. The association between noninvasive oxygenation strategies and lower mortality was less apparent in the sensitivity analysis restricted to patients with more severe hypoxemia. Additional considerations influencing decisions to use these therapies include familiarity with the specific noninvasive oxygenation strategy, perceived patient comfort, ease of deployment, and level of patient monitoring required.

The results of this study also showed a significant association with a lower risk of intubation but not mortality with the use of high-flow nasal oxygen when compared with standard oxygen therapy. These findings are consistent with other recent systematic reviews.14,15 However, the sensitivity analysis using optimistic priors suggested there may still be a potential benefit of high-flow nasal oxygen in reducing mortality. Overall, these discordant conclusions reinforce the need for additional RCTs of high-flow nasal oxygen therapy to treat acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, an assumption of the network meta-analysis is that the individual trials enrolled similar populations and that the intervention protocols were also similar across different studies. The analyses demonstrated only minimal incoherence, specifically in the comparison of high-flow nasal oxygen vs face mask noninvasive ventilation, which could be partially explained by the influence of 1 large trial and the partial inclusion of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and congestive heart failure.7 Trials that predominantly targeted patients with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart failure were excluded, but several trials in this network meta-analysis included some of these patients, potentially leading to an overestimation of the beneficial effect of noninvasive ventilation strategies for patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.6,39,44 However, the overall findings, in particular for endotracheal intubation, were consistent in sensitivity analyses that excluded these trials.

Second, aggregated study-level covariates to conduct this network meta-analysis were not included, and assessment of which patient-level characteristics were associated with an increased likelihood of response to any of these individual therapies could not be conducted.

Third, this study included patients with a range of severity of respiratory failure (based on baseline Pao2:Fio2 ratio), representing a source of potential intransitivity. However, the relative effects of interventions can remain consistent even in the case of different baseline risk of the outcomes.64

Fourth, although helmet noninvasive ventilation had a higher probability to be ranked first, these findings should be assessed with caution. The use of rank probabilities might seem intuitive for clinicians but does not consider the certainty of the evidence, which was deemed to be low for comparisons with helmet noninvasive ventilation. Indeed, the studies evaluating the effectiveness of this intervention were scarce and included a small number of participants when compared with other strategies.29 Therefore, uncertainty remains about the effectiveness of this treatment.

Fifth, the primary studies included in this review have the important limitation of lack of blinding of treatment groups. Although this is unlikely to bias assessment of the primary outcome of all-cause mortality, it is possible that clinicians had different thresholds to provide endotracheal intubation to patients allocated to different treatment groups (eg, helmet noninvasive ventilation).

Sixth, another potential source of heterogeneity is that included studies reported different follow-up times for all-cause mortality. However, the sensitivity analyses that focused on mortality assessed at hospital or intensive care unit discharge yielded results similar to the main analysis.

Conclusions

In this network meta-analysis of trials of adults with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, treatment with noninvasive oxygenation strategies compared with standard oxygen therapy was associated with lower risk of death. Further research is needed to better understand the relative benefits of each strategy.

eAppendix 1. Search Strategies and Eligibility Criteria

eAppendix 2. Further Details on Statistical Analysis

eFigure 1. Initial Pairwise Meta-analysis for All Comparisons

eTable 1. Individual Study Risk of Bias for All-Cause Mortality

eFigure 2. Association of Different Noninvasive Oxygenation Strategies With All-Cause Mortality

eFigure 3. Results of Incoherence Assessment for All-Cause Mortality

eFigure 4. Rank Probabilities for All-Cause Mortality

eTable 2. Summary of Evidence Grading for All Comparison and Primary and Secondary Outcome

eTable 3. Individual Study Risk of Bias for Endotracheal Intubation

eFigure 5. Association of Different Comparisons With Endotracheal Intubation

eFigure 6. Incoherence Assessment for Endotracheal Intubation

eFigure 7. Potential Sources of Incoherence

eFigure 8. Rank Probabilities for Endotracheal Intubation

eFigure 9. Gelman Plots for Model Convergence for All-Cause Mortality

eFigure 10. Gelman Plots for Model Convergence for Endotracheal Intubation

eTable 4. Assessment of Model Fit for Primary and Secondary Outcome

eTable 5. Length of Stay by Treatment Group

eTable 6. Sensitivity Analysis for All-Cause Mortality

eTable 7. Sensitivity Analysis for Endotracheal Intubation

eTable 8. Sensitivity Analysis With Informative Priors for All-Cause Mortality

eTable 9. Sensitivity Analysis With Informative Priors for Intubation

eReferences

Section Editor: Derek C. Angus, MD, MPH, Associate Editor, JAMA (angusdc@upmc.edu).

References

- 1.Scala R, Heunks L. Highlights in acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27(147):180008. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0008-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slutsky AS, Ranieri VM. Ventilator-induced lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2126-2136. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.García-de-Acilu M, Patel BK, Roca O. Noninvasive approach for de novo acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: noninvasive ventilation, high-flow nasal cannula, both or none? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2019;25(1):54-62. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dugan KC, Hall JB, Patel BK. High-flow nasal oxygen-the pendulum continues to swing in the assessment of critical care technology. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2083-2084. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goligher EC, Slutsky AS. Not just oxygen? mechanisms of benefit from high-flow nasal cannula in hypoxemic respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(9):1128-1131. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0006ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonelli M, Conti G, Bufi M, et al. . Noninvasive ventilation for treatment of acute respiratory failure in patients undergoing solid organ transplantation: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2000;283(2):235-241. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frat J-P, Thille AW, Mercat A, et al. ; FLORALI Study Group; REVA Network . High-flow oxygen through nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(23):2185-2196. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemiale V, Mokart D, Resche-Rigon M, et al. ; Groupe de Recherche en Réanimation Respiratoire du patient d’Onco-Hématologie (GRRR-OH) . Effect of noninvasive ventilation vs oxygen therapy on mortality among immunocompromised patients with acute respiratory failure: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(16):1711-1719. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brambilla AM, Aliberti S, Prina E, et al. . Helmet CPAP vs oxygen therapy in severe hypoxemic respiratory failure due to pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(7):942-949. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3325-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doshi P, Whittle JS, Bublewicz M, et al. . High-velocity nasal insufflation in the treatment of respiratory failure: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(1):73-83.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel BK, Wolfe KS, Pohlman AS, Hall JB, Kress JP. Effect of noninvasive ventilation delivered by helmet vs face mask on the rate of endotracheal intubation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2435-2441. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rittayamai N, Tscheikuna J, Praphruetkit N, Kijpinyochai S. Use of high-flow nasal cannula for acute dyspnea and hypoxemia in the emergency department. Respir Care. 2015;60(10):1377-1382. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Q, Gao Y, Chen R, Cheng Z. Noninvasive ventilation with helmet versus control strategy in patients with acute respiratory failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. Crit Care. 2016;20:265. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1449-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rochwerg B, Granton D, Wang DX, et al. . High flow nasal cannula compared with conventional oxygen therapy for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(5):563-572. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05590-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sklar MC, Mohammed A, Orchanian-Cheff A, Del Sorbo L, Mehta S, Munshi L. The impact of high-flow nasal oxygen in the immunocompromised critically ill: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Care. 2018;63(12):1555-1566. doi: 10.4187/respcare.05962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zayed Y, Barbarawi M, Kheiri B, et al. . Initial noninvasive oxygenation strategies in subjects with de novo acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Respir Care. 2019;64(11):1433-1444. doi: 10.4187/respcare.06981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. ; PRISMA-P Group . Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, et al. . The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(11):777-784. doi: 10.7326/M14-2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreyro BL, Angriman F, Munshi L, et al. . Noninvasive oxygenation strategies in adult patients with acute respiratory failure: a protocol for a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01363-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keenan SP, Sinuff T, Burns KE, et al. ; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group/Canadian Critical Care Society Noninvasive Ventilation Guidelines Group . Clinical practice guidelines for the use of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation and noninvasive continuous positive airway pressure in the acute care setting. CMAJ. 2011;183(3):E195-E214. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rochwerg B, Brochard L, Elliott MW, et al. . Official ERS/ATS clinical practice guidelines: noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2):1602426. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02426-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JPTTJ, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.0 Updated July 2019. Accessed May 26, 2020. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook

- 24.Puhan MA, Schünemann HJ, Murad MH, et al. ; GRADE Working Group . A GRADE Working Group approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;349:g5630. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner RM, Jackson D, Wei Y, Thompson SG, Higgins JP. Predictive distributions for between-study heterogeneity and simple methods for their application in bayesian meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2015;34(6):984-998. doi: 10.1002/sim.6381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franchini AJ, Dias S, Ades AE, Jansen JP, Welton NJ. Accounting for correlation in network meta-analysis with multi-arm trials. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3(2):142-160. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, et al. ; LUNG SAFE Investigators; ESICM Trials Group . Noninvasive ventilation of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: insights from the LUNG SAFE study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(1):67-77. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201606-1306OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neupane B, Richer D, Bonner AJ, Kibret T, Beyene J. Network meta-analysis using R: a review of currently available automated packages. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(2):163-171. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Valkenhoef G, Dias S, Ades AE, Welton NJ. Automated generation of node-splitting models for assessment of inconsistency in network meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2016;7(1):80-93. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins JP, Jackson D, Barrett JK, Lu G, Ades AE, White IR. Consistency and inconsistency in network meta-analysis: concepts and models for multi-arm studies. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3(2):98-110. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goligher EC, Tomlinson G, Hajage D, et al. . Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and posterior probability of mortality benefit in a post hoc bayesian analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(21):2251-2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azevedo J, Montenegro W, Leitao A, Silva M, Prazeres J, Maranhao J. High flow nasal cannula oxygen (HFNC) versus non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2015;3(suppl 1):A166. doi: 10.1186/2197-425X-3-S1-A166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azoulay E, Lemiale V, Mokart D, et al. . Effect of high-flow nasal oxygen vs standard oxygen on 28-day mortality in immunocompromised patients with acute respiratory failure: the HIGH randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2099-2107. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell N, Hutchinson CL, Green TC, Rogan E, Bein KJ, Dinh MM. Randomised control trial of humidified high flow nasal cannulae versus standard oxygen in the emergency department. Emerg Med Australas. 2015;27(6):537-541. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Confalonieri M, Potena A, Carbone G, Porta RD, Tolley EA, Umberto Meduri G. Acute respiratory failure in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective randomized evaluation of noninvasive ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5 pt 1):1585-1591. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9903015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cosentini R, Brambilla AM, Aliberti S, et al. . Helmet continuous positive airway pressure vs oxygen therapy to improve oxygenation in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized, controlled trial. Chest. 2010;138(1):114-120. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delclaux C, L’Her E, Alberti C, et al. . Treatment of acute hypoxemic nonhypercapnic respiratory insufficiency with continuous positive airway pressure delivered by a face mask: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;284(18):2352-2360. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.18.2352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrer M, Esquinas A, Leon M, Gonzalez G, Alarcon A, Torres A. Noninvasive ventilation in severe hypoxemic respiratory failure: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(12):1438-1444. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-072OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hernandez G, Fernandez R, Lopez-Reina P, et al. . Noninvasive ventilation reduces intubation in chest trauma-related hypoxemia: a randomized clinical trial. Chest. 2010;137(1):74-80. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He H, Sun B, Liang L, et al. ; ENIVA Study Group . A multicenter RCT of noninvasive ventilation in pneumonia-induced early mild acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):300. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2575-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hilbert G, Gruson D, Vargas F, et al. . Noninvasive ventilation in immunosuppressed patients with pulmonary infiltrates, fever, and acute respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(7):481-487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jaber S, Lescot T, Futier E, et al. ; NIVAS Study Group . Effect of noninvasive ventilation on tracheal reintubation among patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure following abdominal surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1345-1353. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones PG, Kamona S, Doran O, Sawtell F, Wilsher M. Randomized controlled trial of humidified high-flow nasal oxygen for acute respiratory distress in the emergency department: the HOT-ER study. Respir Care. 2016;61(3):291-299. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lemiale V, Mokart D, Mayaux J, et al. . The effects of a 2-h trial of high-flow oxygen by nasal cannula versus Venturi mask in immunocompromised patients with hypoxemic acute respiratory failure: a multicenter randomized trial. Crit Care. 2015;19:380. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1097-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin TJ, Hovis JD, Costantino JP, et al. . A randomized, prospective evaluation of noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(3 Pt 1):807-813. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9808143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Squadrone V, Coha M, Cerutti E, et al. ; Piedmont Intensive Care Units Network (PICUN) . Continuous positive airway pressure for treatment of postoperative hypoxemia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(5):589-595. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Squadrone V, Massaia M, Bruno B, et al. . Early CPAP prevents evolution of acute lung injury in patients with hematologic malignancy. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(10):1666-1674. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1934-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wermke M, Schiemanck S, Höffken G, Ehninger G, Bornhäuser M, Illmer T. Respiratory failure in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic SCT—a randomized trial on early non-invasive ventilation based on standard care hematology wards. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47(4):574-580. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wysocki M, Tric L, Wolff MA, Millet H, Herman B. Noninvasive pressure support ventilation in patients with acute respiratory failure: a randomized comparison with conventional therapy. Chest. 1995;107(3):761-768. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.3.761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhan Q, Sun B, Liang L, et al. . Early use of noninvasive positive pressure ventilation for acute lung injury: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):455-460. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232d75e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grieco DL, Menga LS, Eleuteri D, Antonelli M. Patient self-inflicted lung injury: implications for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and ARDS patients on non-invasive support. Minerva Anestesiol. 2019;85(9):1014-1023. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.19.13418-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nava S, Hill N. Non-invasive ventilation in acute respiratory failure. Lancet. 2009;374(9685):250-259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60496-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Esquinas Rodriguez AM, Papadakos PJ, Carron M, et al. . Clinical review: helmet and non-invasive mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2013;17(2):223. doi: 10.1186/cc11875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brochard L, Mancebo J, Wysocki M, et al. . Noninvasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(13):817-822. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509283331301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bott J, Carroll MP, Conway JH, et al. . Randomised controlled trial of nasal ventilation in acute ventilatory failure due to chronic obstructive airways disease. Lancet. 1993;341(8860):1555-1557. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90696-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lightowler JV, Wedzicha JA, Elliott MW, Ram FS. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation to treat respiratory failure resulting from exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;326(7382):185. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bersten AD, Holt AW, Vedig AE, Skowronski GA, Baggoley CJ. Treatment of severe cardiogenic pulmonary edema with continuous positive airway pressure delivered by face mask. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(26):1825-1830. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112263252601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mehta S, Jay GD, Woolard RH, et al. . Randomized, prospective trial of bilevel versus continuous positive airway pressure in acute pulmonary edema. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(4):620-628. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199704000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carteaux G, Millán-Guilarte T, De Prost N, et al. . Failure of noninvasive ventilation for de novo acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: role of tidal volume. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(2):282-290. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brochard L, Slutsky A, Pesenti A. Mechanical ventilation to minimize progression of lung injury in acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(4):438-442. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1081CP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Jong A, Calvet L, Lemiale V, et al. . The challenge of avoiding intubation in immunocompromised patients with acute respiratory failure. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2018;12(10):867-880. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2018.1511430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Telias I, Katira BH, Brochard L. Is the prone position helpful during spontaneous breathing in patients with COVID-19? JAMA. Published online May 15, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jansen JP, Fleurence R, Devine B, et al. . Interpreting indirect treatment comparisons and network meta-analysis for health-care decision making: report of the ISPOR Task Force on Indirect Treatment Comparisons Good Research Practices: part 1. Value Health. 2011;14(4):417-428. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Search Strategies and Eligibility Criteria

eAppendix 2. Further Details on Statistical Analysis

eFigure 1. Initial Pairwise Meta-analysis for All Comparisons

eTable 1. Individual Study Risk of Bias for All-Cause Mortality

eFigure 2. Association of Different Noninvasive Oxygenation Strategies With All-Cause Mortality

eFigure 3. Results of Incoherence Assessment for All-Cause Mortality

eFigure 4. Rank Probabilities for All-Cause Mortality

eTable 2. Summary of Evidence Grading for All Comparison and Primary and Secondary Outcome

eTable 3. Individual Study Risk of Bias for Endotracheal Intubation

eFigure 5. Association of Different Comparisons With Endotracheal Intubation

eFigure 6. Incoherence Assessment for Endotracheal Intubation

eFigure 7. Potential Sources of Incoherence

eFigure 8. Rank Probabilities for Endotracheal Intubation

eFigure 9. Gelman Plots for Model Convergence for All-Cause Mortality

eFigure 10. Gelman Plots for Model Convergence for Endotracheal Intubation

eTable 4. Assessment of Model Fit for Primary and Secondary Outcome

eTable 5. Length of Stay by Treatment Group

eTable 6. Sensitivity Analysis for All-Cause Mortality

eTable 7. Sensitivity Analysis for Endotracheal Intubation

eTable 8. Sensitivity Analysis With Informative Priors for All-Cause Mortality

eTable 9. Sensitivity Analysis With Informative Priors for Intubation

eReferences