In this study, we utilized the RNAi technique to investigate the functions of PlBZP32, which possesses a basic leucine zipper (bZIP)-PAS structure, and provided insights into the contributions of bZIP transcription factors to oxidative stress, the production of sporangia, the germination of cysts, and the pathogenicity of Peronophythora litchii. This study also revealed the role of PlBZP32 in regulating the enzymatic activities of extracellular peroxidases and laccases in the plant-pathogenic oomycete.

KEYWORDS: Peronophythora litchii, bZIP transcription factor, pathogenicity, peroxidase, laccase

ABSTRACT

Basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors are widespread in eukaryotes, including plants, animals, fungi, and oomycetes. However, the functions of bZIPs in oomycetes are rarely known. In this study, we identified a bZIP protein possessing a special bZIP-PAS structure in Peronophythora litchii, named PlBZP32. We found that PlBZP32 is upregulated in zoospores, in cysts, and during invasive hyphal growth. We studied the functions of PlBZP32 using the RNAi technique to suppress the expression of this gene. PlBZP32-silenced mutants were more sensitive to oxidative stress, showed a lower cyst germination rate, and produced more sporangia than the wild-type strain SHS3. The PlBZP32-silenced mutants were also less invasive on the host plant. Furthermore, we analyzed the activities of extracellular peroxidases and laccases and found that silencing PlBZP32 decreased the activities of P. litchii peroxidase and laccase. To our knowledge, this is the first report that the functions of a bZIP-PAS protein are associated with oxidative stress, asexual development, and pathogenicity in oomycetes.

IMPORTANCE In this study, we utilized the RNAi technique to investigate the functions of PlBZP32, which possesses a basic leucine zipper (bZIP)-PAS structure, and provided insights into the contributions of bZIP transcription factors to oxidative stress, the production of sporangia, the germination of cysts, and the pathogenicity of Peronophythora litchii. This study also revealed the role of PlBZP32 in regulating the enzymatic activities of extracellular peroxidases and laccases in the plant-pathogenic oomycete.

INTRODUCTION

Lychee (or litchi; Litchi chinensis Sonn.) is a famous tropical and subtropical fruit with high economic value due to its appearance, taste, and nutrition, and its production is approximately 3.5 million tons worldwide each year (1, 2). Downy blight caused by Peronophythora litchii is one of the most destructive diseases of lychee during production and postharvest (3, 4).

In plant-microbe interactions, one of the most rapid plant defense reactions is the oxidative burst, which constitutes the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide and H2O2 generated by NADPH oxidases (5, 6). The accumulation of ROS at the site of pathogen invasion can either directly kill the pathogen (7, 8) or function as a second messenger to induce the expression of various plant defense-related genes and to trigger pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP)-triggered immunity (PTI) in plants (9–12).

The transcription factors (TFs) of the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) family are multifunctional across pathogenic fungi. For example, MoAtf1 regulates the transcription of genes encoding laccases and peroxidases, the oxygen scavengers, and thus is required for full virulence in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae (13). MoAP1 also mediates the oxidative stress response and is critical for growth, conidium formation, and pathogenicity in M. oryzae (14). In another plant-pathogenic fungus, Fusarium oxysporum, HapX mediates iron homeostasis; therefore, it is essential for rhizosphere competence and virulence of this pathogen (15). In the human pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans, Gsb1 is required for oxidative stress response, mating, and virulence (16). The Yap1-involved H2O2 detoxification is also associated with virulence in Ustilago maydis (17), Candida albicans (18), Alternaria alternata (19), Verticillium dahliae (20), Aspergillus parasiticus (21), and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (22). However, in Cochliobolus heterostrophus and Aspergillus fumigatus, CHAP1 and AfYap1 are associated with the sensitivity against H2O2 and menadione but are not essential for virulence (23, 24).

Oomycetes, which include many notorious plant pathogens, are fungus-like organisms; however, they are evolutionarily related to brown algae and belong to the kingdom Stramenopila (25). Systematic analysis identified conventional bZIPs and novel bZIP transcription factors in Phytophthora infestans (26), Phytophthora ramorum, and Phytophthora sojae (27, 28). Several bZIPs from P. sojae are upregulated by H2O2 treatment (28). Using stable gene silencing analyses, several P. infestans bZIPs were found to play roles in protecting the pathogen from hydrogen peroxide-induced injury (26). The novel P. infestans bZIP PITG_11668 was nucleus localized, suggesting that it is an authentic transcription factor (26). Pibzp1 from P. infestans was functionally characterized, which interacts with a protein kinase and is required for zoospore motility and plant infection (29).

A Per-ARNT-Sim (PAS)-containing bZIP transcription factor was annotated in P. sojae, named PsBZPc32 (28), but without functional characterization. In this study, we identified the PsBZPc32 ortholog in P. litchii named PlbZIP32. We analyzed the sequences of BZP32 orthologs, as well as the transcriptional profile of PlBZP32. We further characterized the function of the PlbZIP32 gene in oxidative stress response, asexual sporulation, and pathogenicity. Our results showed that PlBZP32 is required for the asexual development, oxidative stress response, and pathogenicity of P. litchii.

RESULTS

PlBZP32 gene belongs to a bZIP transcription factor family and is upregulated in zoospores, cysts, and late stages of infection.

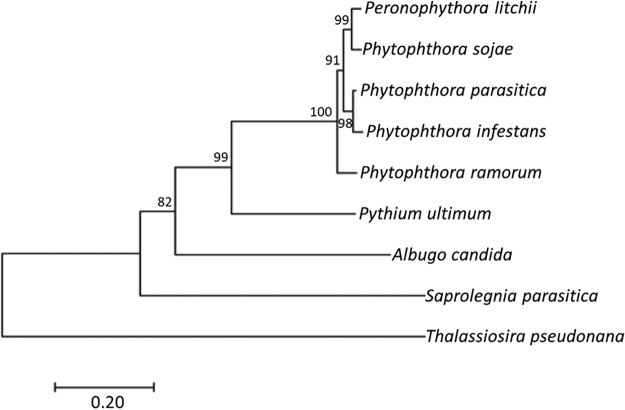

P. litchii BZP32 (PlBZP32) is the ortholog of P. sojae BZPc32, which encodes a bZIP transcription factor and possess a unique bZIP-PAS structure (30). There are 50 bZIP transcription factors in P. litchii based on a search with the Batch CD-search tool (CDD; in NCBI) (31), while PlBZP32 is the only one containing a bZIP-PAS structure (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Here, we also searched the orthologous proteins from P. infestans, P. parasitica, P. ramorum, Pythium ultimum, Albugo candida, Saprolegnia parasitica, and Thalassiosira pseudonana for sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis. PlBZP32 is a 392-amino acid (aa) protein with a bZIP domain located in aa positions 246 to 294 and a PAS domain located in aa positions 304 to 376 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We found that the bZIP domain-PAS structure is conserved in all the orthologs examined here (Fig. S1). Phylogenetic analysis showed that these kinds of bZIP transcription factors are widespread and conserved in oomycetes and algae, while Thalassiosira pseudonana is outside the oomycete group (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of PlBZP32 protein and its orthologs. The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbor-joining method (47). Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 (48).

Sequences of P. litchii bZIP transcription factors. Download Table S1, XLSX file, 0.05 MB (53.4KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2020 Kong et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Amino acid sequence alignment of PlBZP32 and its orthologs from P. sojae, P. parasitica, P. ramorum, P. infestans, Pythium ultimum, Albugo candida, Saprolegnia parasitica, and Thalassiosira pseudonana. The dark red and blue boxes represent bZIP domains and PAS domains, respectively. Download FIG S1, JPG file, 1.0 MB (987.9KB, jpg) .

Copyright © 2020 Kong et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

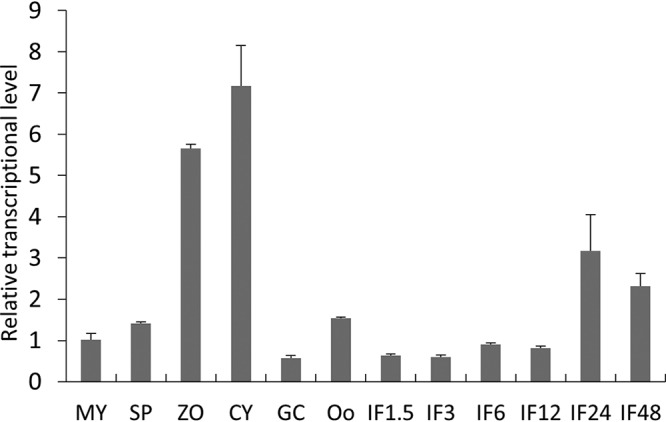

To investigate the biological function of PlBZP32, we first examined the transcriptional profile of the PlBZP32 gene in various growth stages, including mycelia, sporangia, zoospores, cysts, germinating cysts, and oospores, and in infection stages, including 1.5, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h postinoculation. Our results showed that PlBZP32 was upregulated in zoospores, cysts, and late stages of infection compared with that of the vegetative mycelial growth stage (Fig. 2), suggesting that PlBZP32 might function in these specific stages.

FIG 2.

Transcriptional profile of the PlBZP32 gene. Relative transcriptional levels of PlBZP32 were determined by qRT-PCR with total RNA extracted from specific stages of the life cycle. MY, mycelia; SP, sporangia; ZO, zoospores; CY, cysts; GC, germinating cysts; Oo, oospores; IF1.5 to IF48, infection stages of 1.5, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h postinoculation. Transcriptional levels were normalized using the MY values as “1,” and the P. litchii ACTIN gene served as an internal control. The experiment was repeated three times with independent samples.

Generation of PlBZP32-silenced transformants.

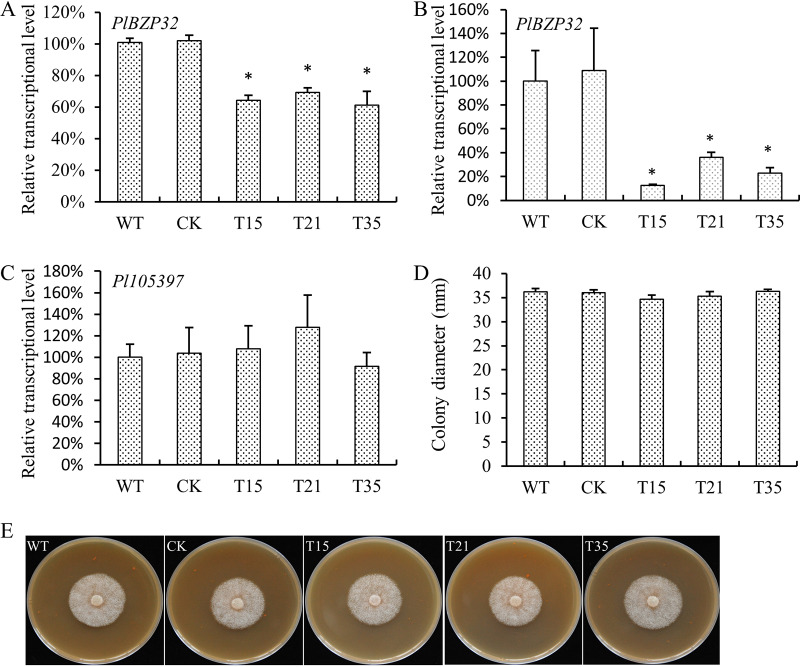

To generate the PlBZP32-silenced mutants, we used a polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated protoplast transformation with a pTORmRFP4 vector carrying an antisense full-length copy of PlBZP32. We obtained 182 transformants by antibiotic resistance screening. These transformants were confirmed by genomic PCR and subsequent quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR). Among them, three transformants (T15, T21, and T35) showed significant reduction in PlBZP32 transcriptional levels in mycelium and zoospore, compared with the wild-type strain SHS3 and the CK strain in which the backbone vector pTORmRFP4 was transformed (Fig. 3A and B). Considering that homology-based transcriptional silencing might cause off-target effects, especially those affecting the expression of neighboring gene(s) (32, 33), we searched the neighboring locus of PlBZP32 and found one gene (Pl105397; GenBank accession number MT396990) 875 nucleotides (nt) away from PlBZP32. Pl105397 encodes a structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) protein containing a Discs-large homologous regions (DHR) domain. The transcriptional level of Pl105397 in PlBZP32-silenced transformants was also examined, and no significant difference was achieved compared with wild-type and CK strains (Fig. 3C).

FIG 3.

PlBZP32 was not required for the mycelial growth of P. litchii. (A, B) Relative transcriptional levels of PlBZP32 in wild type (WT), CK (transformed with empty vector), and transformants. PlBZP32 transcription was normalized to that of the WT value (set as “1.0”). The P. litchii ACTIN gene served as an internal control. RNA used in qRT-PCR was extracted from mycelium (A) and zoospore (B). (C) Transcriptional level of Pl105397 in WT, CK, and PlBZP32-silenced transformants. (D) Colony diameter of WT, CK, and the three PlBZP32-silenced transformants. Bar charts A to D depict means ± SD derived from 3 independent repeats, each of which contained 3 replicates. Asterisks on the bars denote significant difference (P < 0.05) based on Duncan’s multiple range test method. (E) WT, CK, and the PlBZP32-silenced transformants were inoculated on CJA medium for 3 days at 28°C in darkness and then photographed. These experiments were repeated three times.

We checked the growth of these PlBZP32-silenced transformants in comparison with wild-type and CK strains. We measured the colony diameter of these strains at 3 days after inoculation and found that the silencing of the PlBZP32 gene did not affect the growth of P. litchii when cultured on carrot juice agar (CJA) medium (Fig. 3D and E).

PlBZP32-silenced mutants were more sensitive to oxidative stress.

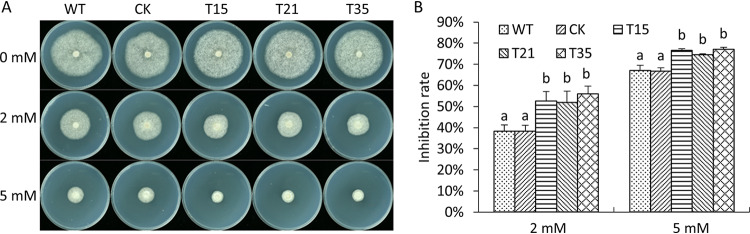

To investigate whether PlBZP32 is involved in the response to oxidative stress, the PlBZP32-silenced mutants and wild-type strain were exposed to H2O2 concentrations of 2 and 5 mM, respectively. The PlBZP32-silenced mutants displayed a greater growth inhibition rate than the wild-type and CK strains (Fig. 4). These results suggested that PlBZP32 is required for resistance to oxidative stress.

FIG 4.

The PlBZP32-silenced mutants were hypersensitive to H2O2. (A) The wild type (WT), CK, and PlBZP32-silenced mutants were inoculated on Plich medium with or without 2 or 5 mM H2O2 and cultured at 25°C for 7 days. (B) The colony diameters of the tested strains were measured. Wild-type and CK strains were used as controls. The growth inhibition rate was calculated using the following formula: (the diameter of control − the diameter of treated strain)/(the diameter of control) ×100%. The bar chart depicts means ± SD derived from 3 independent repeats, and different letters represent a significant difference (P < 0.05) based on Duncan’s multiple range test method.

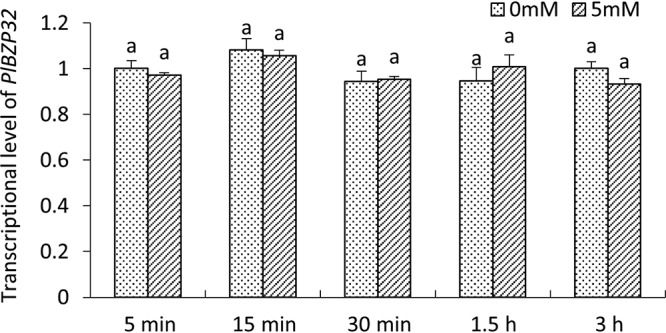

We also analyzed the transcription levels of PlBZP32 after treatment with 5 mM H2O2. We found no significant changes in the transcription level of PlBZP32 from 5 minutes to 3 h posttreatment, compared with the untreated control (Fig. 5). These results suggests that the involvement of PlBZP32 in oxidative stress management might be not associated with a transcription-level regulation of this gene.

FIG 5.

Transcription of PlBZP32 during H2O2 treatment. P. litchii mycelia were treated with 5 mM H2O2 for 5 min, 15 min, 30 min, 1.5 h, and 3 h, before collection for total RNA extraction and qRT-PCR analysis. Expression of the PlBZP32 gene in the untreated mycelia collected at 5 min was used as a reference and normalized to 1.0. The bar chart depicts means ± SD derived from 3 independent repeats. The same letter on the top of bars represents no significant difference (P > 0.05), based on Duncan’s multiple range test method.

Silencing of PlBZP32 impaired the pathogenicity of P. litchii.

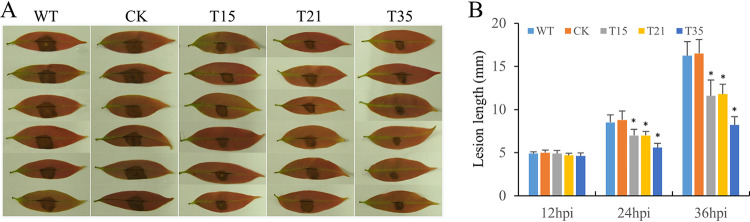

The production and accumulation of reactive oxygen species, the oxidative burst, has been shown to occur in plant-pathogen interactions, such as H2O2 and O2−, directly acting as antimicrobial agents (34, 35). Given that silencing of PlBZP32 decreased the resistance of P. litchii to H2O2, we next analyzed whether PlBZP32 is involved in the pathogenicity of this pathogen. PlBZP32-silenced mutants and the wild-type strain were inoculated on lychee leaves. At 12, 24, and 36 h after inoculation, we measured the diameter of lesions. The results showed that the lesions caused by PlBZP32-silenced mutants were significantly smaller than that caused by wild-type and CK strains (Fig. 6), indicating that PlBZP32 is required for the full pathogenicity of P. litchii.

FIG 6.

PlBZP32 was required for full virulence of P. litchii. (A) Wild type (WT), CK, and three PlBZP32-silenced mutants (T15, T21, and T35) were inoculated on lychee leaves and kept at 25°C in the dark. Photographs were taken 36 h postinoculation (hpi). Representative images for each instance were displayed. (B) Lesion length was measured at 12, 24, and 36 hpi. The values are means ± SD derived from three independent biological repeats (n = 12 leaves for each strain). Asterisks denote a significant difference (P < 0.05) based on Duncan’s multiple range test method.

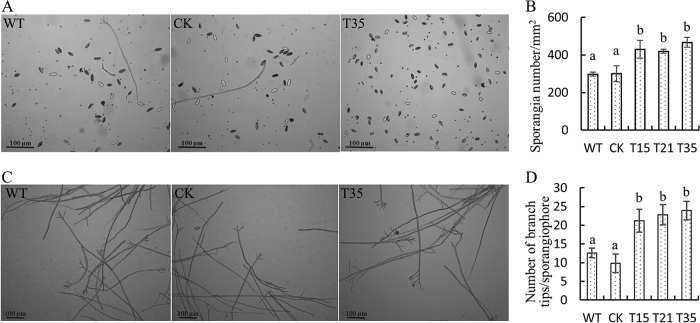

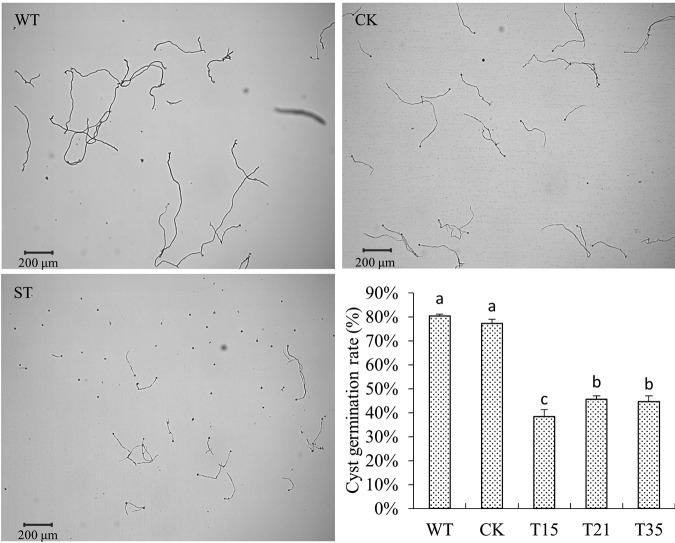

Silencing of PlBZP32 affected the production of sporangia and germination of cysts.

Transcriptional profiling analyses showed that the PlBZP32 gene was upregulated in asexual stages (zoospore and cyst) of P. litchii, so we also analyzed the production of sporangia and the germination rate of cysts. Our results showed that PlBZP32-silenced mutants produced approximately 40% to 50% more sporangia than wild-type and CK strains (Fig. 7A and B) and each sporangiophore of PlBZP32-silenced mutants produced more branch tips and sporangia (Fig. 7C and D). We tested the germination rate of cysts and found it was significantly decreased in the PlBZP32-silenced mutants. The germination rate of cysts is less than 50% in PlBZP32-silenced mutants, whereas it was approximately 80% in wild-type or nonsilenced strains (Fig. 8). However, the silencing of PlBZP32 did not significantly affect the length and germination of sporangia (see Fig. S2 and S3 in the supplemental material). Thus, PlBZP32 may negatively regulate the sporangium production and positively regulate the cyst germination.

FIG 7.

PlBZP32-silenced mutants produced more sporangia. (A, B) Sporangia were quantified at 5 days after inoculation. Bar chart represents mean ± SD (C, D). Branch tips of each sporangiophore were counted. These results are derived from three independent biological repeats, each of which contained 5 technical replicates. Different letters represent a significant difference (P < 0.05) based on Duncan’s multiple range test method.

FIG 8.

Silencing of PlBZP32 impaired cyst germination of P. litchii. Cyst germination was quantified at 2 h after cyst formation. In the bar graph, mean values present the cyst germination rates of PlBZP32-silenced mutants or control strains. Different letters represent a significant difference (P < 0.05) based on Duncan’s multiple range test method. This experiment was repeated three times. Scale bars, 200 μm.

Silencing of PlBZP32 did not affect the sporangia. The length of sporangia was measured; there is no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) using the Student’s t test. The bar chart represents mean ± SD derived from three independent biological repeats. Download FIG S2, TIF file, 0.1 MB (136.5KB, tif) .

Copyright © 2020 Kong et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

PlBZP32 is not required for sporangium germination of P. litchii. The sporangium germination was calculated 2 hours after sporangia were collected. Bar chart represents mean ± SD derived from three independent biological repeats. Download FIG S3, TIF file, 0.2 MB (161.2KB, tif) .

Copyright © 2020 Kong et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

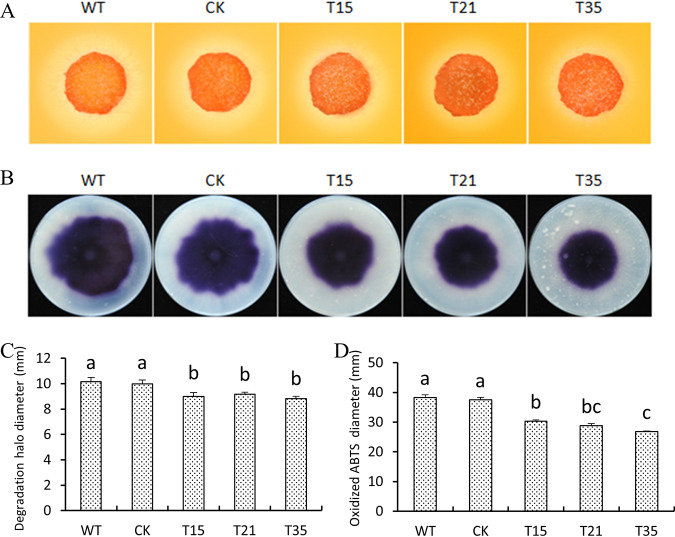

PlBZP32 disruption attenuates the activities of extracellular peroxidases and laccases.

Peroxidase and laccase have been reported to be involved in the resistance of ROS and, thus, critical for fungal pathogenicity (14, 36). Given that the PlBZP32-silenced mutants displayed reduced pathogenicity compared with the wild-type (WT) and nonsilenced strains, we further analyzed the peroxidase and laccase activities in these strains.

Extracellular peroxidase activity was assessed based on Congo red (CR) degradation (37). As shown in Fig. 9A and C, diameters of the degradation halos caused by the three PlBZP32-silenced mutants were reduced compared with the controls. On the other hand, the activities of the extracellular laccase were measured by an oxidation assay of ABTS [2,2′-azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazolinesulfonic acid)] (37). Three PlBZP32-silenced mutants showed a significantly decreased accumulation of ABTS, as visualized by dark purple staining around the mycelial mat, compared with the nonsilenced and wild-type strains (Fig. 9B and D).

FIG 9.

PlBZP32 regulated activities of extracellular peroxidases and laccases. (A) Peroxidase activity assay. Mycelial mats of WT, CK, and three PlBZP32-silenced transformants were inoculated onto solid Plich medium containing Congo red at a final concentration of 500 μg/ml, as an indicator. The discoloration of Congo red was observed after incubation for 1 day. (B) Laccase activity assay. Mycelial mats of the aforementioned strains were inoculated on lima bean agar (LBA) media containing 0.2 mM ABTS for 10 days. (C) The discoloration halo diameters were measured at 1 day postinoculation. (D) The diameters of oxidized ABTS (dark purple) were measured at 10 days postinoculation. Different letters in (C) and (D) bar charts represent a significant difference (P < 0.05) based on Duncan’s multiple range test method. These two experiments contains three independent biological repeats, each of which contained three replicas.

DISCUSSION

In oomycetes, bZIP transcription factors are a large protein family. Fifty bZIP transcription factors were identified in P. litchii; 71 bZIP transcription factors were predicted from P. sojae, of which 45 were confirmed by CDD (NCBI conserved domain database) or the SMART database (28); 22 bZIPs were identified in P. ramorum (27); and 38 bZIPs were identified in P. infestans (26). Based on transcriptional analysis, several P. sojae infection-associated bZIPs were regulated by H2O2 treatment (28). Several bZIP proteins from P. infestans were functionally characterized and only Pibzp1 was found essential for virulence (26, 29). In our study, we identified and analyzed a bZIP transcription factor, PlBZP32, which is an ortholog of P. sojae BZPc32 and possesses a bZIP-PAS structure.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene disruption in P. sojae was established in 2016 (38), and our group also succeeded in disrupting PlPAE4 and PlPAE5 genes using this technique (39). However, we failed to knock out PlBZP32 in P. litchii, suggesting that it might be an essential gene. Therefore, we investigated the function of PlBZP32 by a gene silencing strategy. We obtained only 3 PlBZP32-silenced transformants out of 182 transformants screened by antibiotic resistance. The silencing efficiency of this gene is much lower than that of PlMAPK10, as reported by our group previously (40). Out of all the G418-resistant transformants, only around 37% contain the empty vector, based on PCR verification. This gene was downregulated by 31% to 39% in the mycelia of the three PlBZP32-silenced transformants and 65% to 87% in the zoospores. The efficiency of downregulating this gene expression seems higher in zoospores than in mycelia, likely because the transcriptional level of PlBZP32 is highly expressed in zoospores compared to mycelia. The gene silencing strategy might affect other genes with high identity in the sequence. However, other P. litchii BZP-encoding genes showed less than 51% identity with PlBZP32; thus, we assumed that our targeted silencing of PlBZP32 may not affect the expression of other BZP-encoding genes. On the other hand, homology-based transcriptional silencing may also cause off-target effects on the neighboring gene(s) (32, 33), but we managed to confirm that it did not happen to the annotated gene Pl105397 that was proximal to the PlBZP32 locus.

The production of sporangia and germination of cysts are very important for the asexual reproduction, dissemination, and infection of P. litchii. In this study, the PlBZP32-silencing mutants produced more sporangia but with reduced germination rate of cysts, and the sporangial germination rate was not affected by silencing of PlBZP32. These results suggested that PlBZP32 might be a negative regulator in the production of sporangia and a positive regulator in the germination of cysts.

We further found that PlBZP32 is required for the full virulence of P. litchii and its resistance to oxidative stress caused by H2O2. This may indicate that PlBZP32 regulates P. litchii virulence via resistance to oxidative stress. In supporting this hypothesis, we found that the enzymatic activities of ROS scavenger peroxidases and laccases were both decreased in the PlBZP32-silencing mutants. This finding is consistent with the report of M. oryzae MoAP1 (14). However, the direct target genes of the PlBZP32 transcription factor in regulating oxidative resistance and/or pathogenicity of P. litchii are unclear.

PAS domain-containing proteins detect a wide range of physical and chemical stimuli and associate with a series of signal transduction systems (41). PlBZP32 contains a PAS domain immediately following the bZIP domain, suggesting that it might interact with some small ligand through a different pathway than other bZIP transcription factors. Further study is needed for characterizing the function of the PAS domain in bZIP transcription factors.

Overall, our study identified a bZIP transcription factor responsible for P. litchii development, oxidative stress response, and pathogenicity. At present, we do not fully understand its regulatory mechanism, particularly the function of its PAS domain (and the corresponding ligands/signal molecules) and its downstream target genes. It is also worth further investigating the function diversity (if any) among oomycete species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bioinformatics analysis.

The P. litchii BZP32 (GenBank accession number MT396989) sequence was obtained by a BLAST search using PsBZPc32 as a bait in NCBI (BioProject ID PRJNA290406) (30). Sequences of BZPc32 orthologs in P. sojae (v1.1), P. ramorum (v1.1), P. capsici (v11.0), P. infestans, and T. pseudonana (v3.0) genomes were obtained from the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI) database (genome.jgi.doe.gov), and the BZP32 ortholog in Pythium ultimum was obtained from the Pythium Genome Database (pythium.plantbiology.msu.edu). Orthologs of PlBZP32 in P. parasitica and Albugo candida were obtained from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). All of these sequences were listed in Table S2. The sequence alignment (Muscle algorithm) and phylogenetic tree (neighbor-joining algorithm with 1,000 bootstrap replications) were constructed using the MEGA7 program (http://megasoftware.net).

Sequences of orthologs of PlBZP32 used in this study. Download Table S2, XLSX file, 0.01 MB (12.9KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2020 Kong et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

P. litchii strain and culture conditions.

P. litchii strain SHS3 (wild type) was isolated from Guangdong Province, China, and cultured on carrot juice agar (CJA) medium (juice from 200 g carrot for 1 liter medium, 15 g agar/liter for solid media) at 25°C in the dark. The PlBZP32-silenced transformants were maintained on CJA medium containing 50 μg/ml G418.

Analysis of transcriptional profile of PlBZP32.

Total RNA was extracted using the total RNA kit (catalog [cat.] number R6834-01; Omega,). Samples included mycelia, sporangia, zoospores, cysts, germinating cysts, oospores, and mycelial mats inoculated on expanded tender lychee leaves of 8 to 10 days old for 1.5, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h (40, 42). The first-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA by oligo(dT) priming using a Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase kit (number S28025-014; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The transcription profile of PlBZP32 was analyzed with qRT-PCR, with ACTIN (GenBank accession number MT396988) as an internal control. The primers pairs PlBZPRTF (CCTCTGCGGTGTTCCTTTTC) and PlBZPRTR (CGTGTTGAGCTTCGTGAACA); and PlActF (TCACGCTATTGTTCGTCTGG) and PlActR (TCATCTCCTGGTCGAAGTCC) were used to amplify PlBZP32 and ACTIN, respectively. The relative fold change was calculated using the threshold cycle (2−ΔΔCT) method (43).

Sporangia were harvested by flooding the mycelia, which had been cultured on CJA media for 5 days, with sterile water, then filtering the subsequent suspension through a 100-μm strainer (44). The suspension was incubated with sterile distilled water at 16°C for 2 h for releasing zoospores. For oospore collection, P. litchii strains were inoculated on CJA medium which was covered by an Amersham Hybond membrane. After 10 days, the aerial mycelia were separated from the medium by removing the Amersham Hybond membrane. Then, oospores were scraped from the medium surface and collected.

Transformation of P. litchii.

The full-length open reading frame of PlBZP32 was amplified with primers PlBZP32-BsiwI-F (AAACGTACGATGGACTTCACGTCGCCTAATG) and PlBZP32-ClaI-R (AAAATCGATAATGTCGCGGTCCACAC), using the cDNA from P. litchii strain SHS3 as the template. The amplified PlBZP32 fragment was ligated into the pTORmRFP4 vector digested with ClaI and BsiWI in antisense orientation (45, 46).

PlBZP32-silenced mutants were generated using an established protocol (44). Preliminary transformants were screened on CJA media containing 50 μg/ml G418. PCR screening for PlBZP32-silencing transformants was performed with primers pHAM34-F (GCTTTTGCGTCCTACCATCCG) and PlBZP32-BsiWI-F. The gene silencing efficiency was evaluated with real-time RT-PCR, using the primers, PlBZPRTF/PlBZPRTR and PlActF/PlActR, as listed above.

Pathogenicity assays on lychee leaves.

The 8- to 10-day-old soft expanded lychee leaves were collected from the same plant in an orchard in South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China. The 5-mm hyphal plugs of the PlBZP32-silenced mutants were inoculated on the abaxial side of lychee leaves in a dark box and then were placed in climate room under 80% humidity in the dark at 25°C for 36 h (44). The virulence of each transformant was tested with the wild-type strain (SHS3) and CK strain as positive controls. Lesion length (the longest diameter of the lesion) was measured at 36 h postinoculation. At least three independent repeats were performed for each instance with 12 leaves/repeats.

Extracellular enzyme activity assays.

The detection of peroxidase secretion and laccase activity was performed following the reported procedure (37). The experiments were repeated three times independently, with three technical replicates each time.

Data availability.

Sequences of P. litchii ACTIN, PlBZP32, and Pl105397 were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers MT396988, MT396989, and MT396990, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants to G.K. from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31701771) and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (2017A030310310); grants to P.X. from the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (2019A1515010977 and 2017A020208039); and an earmarked fund to Z.J. from the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-32-11).

We thank Steve Whisson for providing the plasmid pTORmRFP4. We thank Ziqing Zhu for technical assistance and Wenwu Ye for sequence analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jiang YM, Wang Y, Song L, Liu H, Lichter A, Kerdchoechuen O, Joyce DC, Shi J. 2006. Postharvest characteristics and handling of litchi fruit—an overview. Aust J Exp Agric 46:1541–1556. doi: 10.1071/EA05108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qi W, Chen H, Luo T, Song F. 2019. Development status, trend and suggestion of litchi industry in mainland China. Guangdong Nong Ye Ke Xue 46:132–139. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kao C, Leu L. 1980. Sporangium germination of Peronophythora litchii, the causal organism of litchi downy blight. Mycologia 72:737–748. doi: 10.1080/00275514.1980.12021242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu L, Xue J, Wu P, Wang D, Lin L, Jiang Y, Duan X, Wei X. 2013. Antifungal activity of hypothemycin against Peronophythora litchii in vitro and in vivo. J Agric Food Chem 61:10091–10095. doi: 10.1021/jf4030882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apostol I, Heinstein PF, Low PS. 1989. Rapid stimulation of an oxidative burst during elicitation of cultured plant cells: role in defense and signal transduction. Plant Physiol 90:109–116. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doke N, Miura Y, Sanchez LM, Park HJ, Noritake T, Yoshioka H, Kawakita K. 1996. The oxidative burst protects plants against pathogen attack: mechanism and role as an emergency signal for plant bio-defence—a review. Gene 179:45–51. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00423-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamb C, Dixon RA. 1997. The oxidative burst in plant disease resistance. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 48:251–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mellersh DG, Foulds IV, Higgins VJ, Heath MC. 2002. H2O2 plays different roles in determining penetration failure in three diverse plant-fungal interactions. Plant J 29:257–268. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7412.2001.01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torres MA, Dangl JL. 2005. Functions of the respiratory burst oxidase in biotic interactions, abiotic stress and development. Curr Opin Plant Biol 8:397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nurnberger T, Brunner F, Kemmerling B, Piater L. 2004. Innate immunity in plants and animals: striking similarities and obvious differences. Immunol Rev 198:249–266. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang H, Fang Q, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Zheng X. 2009. The role of respiratory burst oxidase homologues in elicitor-induced stomatal closure and hypersensitive response in Nicotiana benthamiana. J Exp Bot 60:3109–3122. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gan Y, Zhang L, Zhang Z, Dong S, Li J, Wang Y, Zheng X. 2009. The LCB2 subunit of the sphingolip biosynthesis enzyme serine palmitoyltransferase can function as an attenuator of the hypersensitive response and Bax-induced cell death. New Phytol 181:127–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo M, Guo W, Chen Y, Dong S, Zhang X, Zhang H, Song W, Wang W, Wang Q, Lv R, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Zheng X. 2010. The basic leucine zipper transcription factor Moatf1 mediates oxidative stress responses and is necessary for full virulence of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 23:1053–1068. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-23-8-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo M, Chen Y, Du Y, Dong Y, Guo W, Zhai S, Zhang H, Dong S, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Wang P, Zheng X. 2011. The bZIP transcription factor MoAP1 mediates the oxidative stress response and is critical for pathogenicity of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS Pathog 7:e1001302. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.López-Berges MS, Capilla J, Turrà D, Schafferer L, Matthijs S, Jöchl C, Cornelis P, Guarro J, Haas H, Pietro AD. 2012. HapX-mediated iron homeostasis is essential for rhizosphere competence and virulence of the soilborne pathogen Fusarium oxysporum. Plant Cell 24:3805–3822. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.098624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheon SA, Thak EJ, Bahn Y, Kang HA. 2017. A novel bZIP protein, Gsb1, is required for oxidative stress response, mating, and virulence in the human pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Sci Rep 7:4044. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04290-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molina L, Kahmann R. 2007. An Ustilago maydis gene involved in H2O2 detoxification is required for virulence. Plant Cell 19:2293–2309. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enjalbert B, MacCallum DM, Odds FC, Brown A. 2007. Niche-specific activation of the oxidative stress response by the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Infect Immun 75:2143–2151. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01680-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin CH, Yang SL, Chung KR. 2009. The YAP1 homolog-mediated oxidative stress tolerance is crucial for pathogenicity of the necrotrophic fungus Alternaria alternata in citrus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 22:942–952. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-8-0942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Deng C, Tian L, Xiong D, Tian C, Klosterman SJ. 2018. The transcription factor VdHapX controls iron homeostasis and is crucial for virulence in the vascular pathogen Verticillium dahliae. mSphere 3:e00400-18. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00400-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wee J, Hong S, Roze LV, Day DM, Chanda A, Linz JE. 2017. The fungal bZIP transcription factor AtfB controls virulence-associated processes in Aspergillus parasiticus. Toxins 9:287. doi: 10.3390/toxins9090287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Wu Y, Liu Z, Zhang C. 2017. The function and transcriptome analysis of a bZIP transcription factor CgAP1 in Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Microbiol Res 197:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lev S, Hadar R, Amedeo P, Baker SE, Yoder OC, Horwitz BA. 2005. Activation of an AP1-like transcription factor of the maize pathogen Cochliobolus heterostrophus in response to oxidative stress and plant signals. Eukaryot Cell 4:443–454. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.2.443-454.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lessing F, Kniemeyer O, Wozniok I, Loeffler J, Kurzai O, Haertl A, Brakhage AA. 2007. The Aspergillus fumigatus transcriptional regulator AfYap1 represents the major regulator for defense against reactive oxygen intermediates but is dispensable for pathogenicity in an intranasal mouse infection model. Eukaryot Cell 6:2290–2302. doi: 10.1128/EC.00267-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavalier-Smith T, Chao EE, Lewis R. 2018. Multigene phylogeny and cell evolution of chromist infrakingdom Rhizaria: contrasting cell organisation of sister phyla Cercozoa and Retaria. Protoplasma 255:1517–1574. doi: 10.1007/s00709-018-1241-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gamboa-Meléndez H, Huerta AI, Judelson HS. 2013. bZIP transcription factors in the oomycete Phytophthora infestans with novel DNA-binding domains are involved in defense against oxidative stress. Eukaryot Cell 12:1403–1412. doi: 10.1128/EC.00141-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rayko E, Maumus F, Maheswari U, Jabbari K, Bowler C. 2010. Transcription factor families inferred from genome sequences of photosynthetic stramenopiles. New Phytol 188:52–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye W, Wang Y, Dong S, Tyler BM, Wang Y. 2013. Phylogenetic and transcriptional analysis of an expanded bZIP transcription factor family in Phytophthora sojae. BMC Genomics 14:839. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blanco FA, Judelson HS. 2005. A bZIP transcription factor from Phytophthora interacts with a protein kinase and is required for zoospore motility and plant infection. Mol Microbiol 56:638–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye W, Wang Y, Shen D, Li D, Pu T, Jiang Z, Zhang Z, Zheng X, Tyler BM, Wang Y. 2016. Sequencing of the litchi downy blight pathogen reveals it is a Phytophthora species with downy mildew-like characteristics. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 29:573–583. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-03-16-0056-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marchler-Bauer A, Bo Y, Han L, He J, Lanczycki CJ, Lu S, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, Lu F, Marchler GH, Song JS, Thanki N, Wang Z, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Zheng C, Geer LY, Bryant SH. 2017. CDD/SPARCLE: functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D200–D203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abrahamian M, Ah-Fong AM, Davis C, Andreeva K, Judelson HS. 2016. Gene expression and silencing studies in Phytophthora infestans reveal infection-specific nutrient transporters and a role for the nitrate reductase pathway in plant pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog 12:e1006097. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vu AL, Leesutthiphonchai W, Ah-Fong AMV, Judelson HS. 2019. Defining transgene insertion sites and off-target effects of homology-based gene silencing informs the application of functional genomics tools in Phytophthora infestans. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 32:915–927. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-09-18-0265-TA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Low PS, Merida JR. 1996. The oxidative burst in plant defense: function and signal transduction. Physiol Plant 96:533–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1996.tb00469.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen X, Wang X, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Zheng X. 2008. Differences in the induction of the oxidative burst in compatible and incompatible interactions of soybean and Phytophthora sojae. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 73:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2008.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mayer AM, Staples RC. 2002. Laccase: new functions for an old enzyme. Phytochemistry 60:551–565. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheng Y, Wang Y, Meijer HJ, Yang X, Hua C, Ye W, Tao K, Liu X, Govers F, Wang Y. 2015. The heat shock transcription factor PsHSF1 of Phytophthora sojae is required for oxidative stress tolerance and detoxifying the plant oxidative burst. Environ Microbiol 17:1351–1364. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fang Y, Tyler BM. 2016. Efficient disruption and replacement of an effector gene in the oomycete Phytophthora sojae using CRISPR/Cas9. Mol Plant Pathol 17:127–139. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong G, Wan L, Deng YZ, Yang W, Li W, Jiang L, Situ J, Xi P, Li M, Jiang Z. 2019. Pectin acetylesterase PAE5 is associated with the virulence of plant pathogenic oomycete Peronophythora litchii. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 106:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2018.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang L, Situ J, Deng YZ, Wan L, Xu D, Chen Y, Xi P, Jiang Z. 2018. PlMAPK10, a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) in Peronophythora litchii, is required for mycelial growth, sporulation, laccase activity, and plant infection. Front Microbiol 9:426. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Möglich A, Ayers RA, Moffat K. 2009. Structure and signaling mechanism of Per-ARNT-Sim domains. Structure 17:1282–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ye W, Wang X, Tao K, Lu Y, Dai T, Dong S, Dou D, Gijzen M, Wang Y. 2011. Digital gene expression profiling of the Phytophthora sojae transcriptome. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 24:1530–1539. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-05-11-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang L, Ye W, Situ J, Chen Y, Yang X, Kong G, Liu Y, Tinashe RJ, Xi P, Wang Y, Jiang Z. 2017. A Puf RNA-binding protein encoding gene PlM90 regulates the sexual and asexual life stages of the litchi downy blight pathogen Peronophythora litchii. Fungal Genet Biol 98:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whisson SC, Boevink PC, Moleleki L, Avrova AO, Morales JG, Gilroy EM, Armstrong MR, Grouffaud S, van West P, Chapman S, Hein I, Toth IK, Pritchard L, Birch PR. 2007. A translocation signal for delivery of oomycete effector proteins into host plant cells. Nature 450:115–118. doi: 10.1038/nature06203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hua C, Meijer HJG, de Keijzer J, Zhao W, Wang Y, Govers F. 2013. GK4, a G-protein-coupled receptor with a phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase domain in Phytophthora infestans, is involved in sporangia development and virulence. Mol Microbiol 88:352–370. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saitou N, Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. 2016. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sequences of P. litchii bZIP transcription factors. Download Table S1, XLSX file, 0.05 MB (53.4KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2020 Kong et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Amino acid sequence alignment of PlBZP32 and its orthologs from P. sojae, P. parasitica, P. ramorum, P. infestans, Pythium ultimum, Albugo candida, Saprolegnia parasitica, and Thalassiosira pseudonana. The dark red and blue boxes represent bZIP domains and PAS domains, respectively. Download FIG S1, JPG file, 1.0 MB (987.9KB, jpg) .

Copyright © 2020 Kong et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Silencing of PlBZP32 did not affect the sporangia. The length of sporangia was measured; there is no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) using the Student’s t test. The bar chart represents mean ± SD derived from three independent biological repeats. Download FIG S2, TIF file, 0.1 MB (136.5KB, tif) .

Copyright © 2020 Kong et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

PlBZP32 is not required for sporangium germination of P. litchii. The sporangium germination was calculated 2 hours after sporangia were collected. Bar chart represents mean ± SD derived from three independent biological repeats. Download FIG S3, TIF file, 0.2 MB (161.2KB, tif) .

Copyright © 2020 Kong et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Sequences of orthologs of PlBZP32 used in this study. Download Table S2, XLSX file, 0.01 MB (12.9KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2020 Kong et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Data Availability Statement

Sequences of P. litchii ACTIN, PlBZP32, and Pl105397 were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers MT396988, MT396989, and MT396990, respectively.