Abstract

Background

Scoliosis in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is usually progressive and is treated with surgery. However, it is unclear whether the existing evidence is sufficiently scientifically rigorous to support a recommendation for spinal surgery for most patients with DMD and scoliosis. This is an updated review, and an updated search was undertaken in which no new studies were found for inclusion.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of spinal surgery in patients with DMD with scoliosis. We intended to test whether spinal surgery is effective in increasing survival and improving respiratory function, quality of life, and overall functioning, and whether spinal surgery is associated with severe adverse effects.

Search methods

On 16 June 2015 we searched the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group Specialized Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL Plus. We also searched ProQuest Dissertation and Thesis database (January 1980 to June 2015), the National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials Database (6 January 2015), and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (17 June 2015), and checked references. We imposed no language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We planned to include controlled clinical trials using random or quasi‐random allocation of treatment evaluating all forms of spinal surgery for scoliosis in patients with DMD in the review. The control interventions would have been no treatment, non‐operative treatment, or a different form of spinal surgery.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by The Cochrane Collaboration. Two review authors independently examined the search results and evaluated the study characteristics against inclusion criteria in order to decide which studies to include in the review.

Main results

Of the 49 relevant studies we found, none met the inclusion criteria for the review because they were not clinical trials, but prospective or retrospective reviews of case series.

Authors' conclusions

Since no randomized controlled clinical trials were available to evaluate the effectiveness of scoliosis surgery in patients with DMD, we can make no good evidence‐based conclusion to guide clinical practice. Patients with scoliosis should be informed as to the uncertainty of benefits and potential risks of surgery for scoliosis. Randomized controlled trials are needed to investigate the effectiveness of scoliosis surgery, in terms of quality of life, functional status, respiratory function, and life expectancy.

Plain language summary

Surgery for curvature of the spine in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Review question

What is the effectiveness and safety of spinal surgery to treat scoliosis in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD)?

Background

Scoliosis, or curvature of the spine, is common in patients with DMD. It is usually progressive, and surgery is often performed to halt its progression, improve cosmetic appearance, facilitate care, preserve upper limb and respiratory function, and hopefully increase life expectancy. We wished to learn whether spinal surgery was better or worse than the alternatives.

Study characteristics

We found no randomized controlled trials.

Key results and quality of the evidence

We found 49 relevant studies, however they were not clinical trials but prospective or retrospective reviews of case series. The quality of evidence was very low because no clinical trial was available. This is an updated review, and an updated search was undertaken in which no new studies were found.

Conclusion

No randomized controlled clinical trials are available to evaluate the effectiveness of scoliosis surgery in patients with DMD. Randomized controlled clinical trials are needed in this group of patients to evaluate the benefits and risks of different surgical treatments.

The evidence is current to 5 January 2015.

Background

Description of the condition

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an inherited X‐linked muscular dystrophy caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene. It is characterized by progressive dystrophic changes in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Progressive weakness in affected children results in loss of ambulation at a mean age of 9.5 years (van Essen 1997). There is progressive cardiomyopathy, and respiratory failure occurs secondary to respiratory muscle weakness. The mean survival in the absence of ventilatory support is 19.5 years (van Essen 1997). In 90% of patients, death is the result of respiratory failure, and in 10% the result of cardiac involvement. There is currently no proven effective curative treatment for this debilitating disease. A systematic review found that glucocorticoid therapy improves muscle strength and function in the short term. However, adverse effects were common and long‐term benefits are uncertain (Manzur 2008).

Spinal deformity, especially scoliosis, is progressive in the majority of patients with DMD (Galasko 1995; Miller 1985). From the onset of spinal deformity, progression can be extremely rapid and impair unsupported sitting ability and further compromise respiratory and cardiac function (Hsu 1983). Kurz observed a 4% decrease in vital capacity for every 10% progression of the spinal curve in patients with DMD (Kurz 1983). Galasko found that on average, vital capacity decreases by 8% per year in patients with scoliosis secondary to DMD (Galasko 1992).

Description of the intervention

Spinal fusion surgery with instrumentation remains the mainstay of treatment for patients with DMD with scoliosis. Commonly used techniques are either based on sublaminar segmental wiring, such as Luque instrumentation, or the modern variants based on segmental pedicle screw and hook fixation such as Isola, Texas Scottish Rite Hospital (TSRH), or Universal Spine System. Two stainless steel or titanium rods are contoured to the desired spinal shape, and the spine reduced onto the rods, either with the sublaminar wires or segmental screws and hooks. Pelvic fixation is rarely required in DMD scoliosis, and the Galveston technique of rod insertion into the ileum, or more modern screw fixation can be used in some circumstances. Postoperative bracing is not required with modern fixation techniques.

Long‐term corticosteroid treatment may slow the progression of scoliosis in patients with DMD and may reduce the need for surgery (Dooley 2010), but adverse effects are frequent (Alman 2004). Non‐operative treatment such as bracing might not prevent the progression of this kind of spinal deformity because of the progressive nature of the underlying muscle disease (Cambridge 1987; Colbert 1987). Therefore, non‐operative treatment is usually considered only in exceptional cases when a person refuses surgery or when a person has a very advanced deformity with poor general health (Forst 1997; Heller 1997; McCarthy 1999).

How the intervention might work

The potential advantages of surgery described in the literature include increased comfort and sitting tolerance (Bridwell 1999; Cambridge 1987; Marchesi 1997; Matsumura 1997; Miller 1991; Miller 1992; Rice 1998; Rideau 1984; Shapiro 1992), cosmetic improvement (Bellen 1993; Bridwell 1999), no need for orthopedic braces (Bellen 1993; Colbert 1987; Miller 1985; Noble Jamieson 1986), easier nursing care by parents (Bellen 1993), and pain relief (Bellen 1993; Galasko 1977; Miller 1991).

Nevertheless, the effects of spinal surgery on respiratory function and life expectancy are still controversial. Some studies reported that spinal fusion had no effects on the natural deterioration of respiratory function of patients with DMD (Kinali 2006; Miller 1988; Miller 1992; Shapiro 1992), at short‐term and five‐year follow‐up (Miller 1991). In contrast, several studies reported stabilization of vital capacity in patients surgically treated for two to eight years (Galasko 1992; Galasko 1995; Rideau 1984; Velasco 2007). Regarding life expectancy, Galasko observed a lower mortality in patients surgically treated (Galasko 1992; Galasko 1995). However, other studies reported that spinal surgery did not improve life expectancy (Chataigner 1998; Gayet 1999; Kennedy 1995; Kinali 2006; Miller 1988). Adverse effects and complications during and after surgery are not uncommon, including ventilator‐associated pneumonia (iatrogenic, in the postoperative period), wound dehiscence, surgical wound infection, hemorrhage, loosening of fixation, pseudarthrosis, deteriorated respiratory function, and increased difficulty with hand‐to‐head motions.

Why it is important to do this review

A randomized trial has demonstrated that although tendon surgery in patients with DMD may correct deformities, it could also result in more rapid deterioration of function in some patients, and there were no beneficial effects on strength or function (Manzur 1992). With increasing use of non‐invasive ventilation in DMD patients with respiratory insufficiency, which may prolong the life expectancy, it is unclear to what extent increased survival is related to non‐invasive ventilation rather than to other interventions, including scoliosis surgery. It remains uncertain whether the existing evidence is sufficiently scientifically rigorous to recommend spinal surgery for most patients with DMD and scoliosis. In this systematic review, we evaluated the effectiveness of various forms of spinal surgery in prolonging life expectancy, retarding the natural deterioration of respiratory function, and improving quality of life in DMD patients. We wanted to evaluate whether the benefits of surgery outweigh the risks in general and determine which patient subgroups are most likely to benefit. The review has been updated, most recently in 2015.

Objectives

The objectives of this systematic review were to determine the effectiveness and safety of spinal surgery in DMD patients with scoliosis. We intended to address whether spinal surgery:

is effective in increasing survival;

can improve respiratory function in the short term and long term;

can improve quality of life and overall functioning;

is associated with severe adverse effects.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We planned to include controlled clinical trials using random or quasi‐random allocation of treatment in the review.

Types of participants

We would include patients with DMD (defined as progressive limb girdle weakness with at least one of: (1) dystrophic changes on muscle biopsy with reduced or absent dystrophin staining; (2) deletion, duplication, or point mutation of dystrophin gene) and all degrees of scoliosis documented by appropriate X‐rays.

It is possible that use of this definition might have resulted in the inclusion of some individuals with an intermediate or severe Becker phenotype. However, the inclusion of only biopsy‐proven dystrophin negative cases could potentially result in the loss of some important data.

Types of interventions

We planned to include trials evaluating all forms of spinal surgery for scoliosis. The control interventions were to be no treatment, non‐operative treatment, or a different form of spinal surgery.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Survival: to allow for studies using different follow‐up periods, we planned to use hazard ratios from survival data regression analysis.

Secondary outcomes

Respiratory function, as measured by pulmonary function tests such as forced vital capacity (FVC): medium term (3 to 12 months) and long term (more than 12 months). The results from studies with differing follow‐up lengths were to be weighted appropriately to allow for this.

Medium‐ and long‐term disability as measured by validated scales such as the Barthel index or Functional Independent Measure.

Medium‐ and long‐term quality of life as measured by validated scales such as the 36‐Item Short‐Form Health Status Survey (SF‐36).

Rate of progression of scoliosis, as measured by change of Cobb angle per year.

Frequency of severe adverse effects and complications, such as death related to surgery, deep surgical wound infection, wound dehiscence, loosening of fixation, pneumonia, pseudarthrosis, and the need for revision surgery.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group Specialized Register (16 June 2015), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2015, Issue 12 in the Cochrane Library), MEDLINE (January 1966 to 16 June 2015), EMBASE (January 1947 to June 2015), CINAHL Plus (January 1937 to June 2015), ProQuest Dissertation and Thesis database (January 1980 to June 2015).

We also searched the following clinical trial registries:

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Trials Database (www.ClinicalTrials.gov, accessed on 17 June 2015)

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/en/, accessed on 17 June 2015)

Electronic searches

The detailed search strategies are in the appendices: MEDLINE (Appendix 1), EMBASE (Appendix 2), CENTRAL (Appendix 3), CINAHL Plus (Appendix 4), ProQuest Dissertation and Thesis database (Appendix 5), and the clinical trial registry databases (Appendix 6).

We used no language restriction in the search and inclusion of studies. However, we excluded multiple publications reporting the same group of patients or its subsets.

Searching other resources

The review authors searched the reference lists of all relevant papers for further studies. The process of searching many different sources might have brought to light direct or indirect references to unpublished studies. We planned to seek to obtain copies of such unpublished material. In addition, we contacted colleagues and experts in the field to identify any unpublished or ongoing studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (DC and VW) independently reviewed titles and abstracts of references retrieved from the searches and selected all potentially relevant studies. We obtained copies of these articles, and the same review authors independently checked them against the inclusion criteria of the review. The review authors were not blinded to the names of the trial authors, institutions, or journal of publication. We planned that the same review authors (DC and VW) would independently extract data from included trials and assess trial quality. We would have resolved any disagreements by consensus.

Additional methods not applicable because of the lack of included studies are shown in Appendix 7.

Results

Description of studies

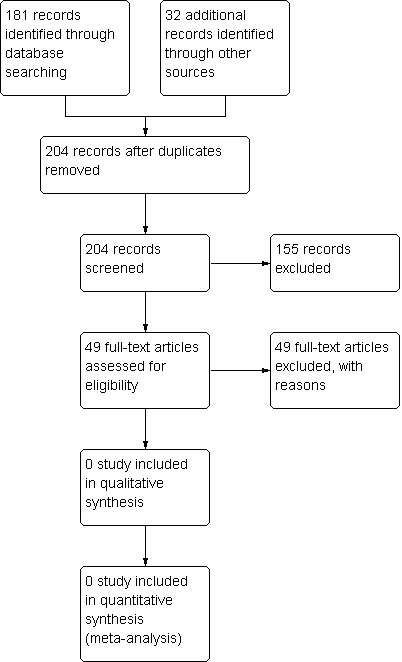

In January 2015, we found a total of 181 studies on electronic search of the databases (Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group Specialized Register: one study, CENTRAL: one study, MEDLINE: 22 studies, EMBASE: 15 studies, CINAHL Plus: 15 studies, ProQuest Dissertation and Thesis database: 126 studies, NIH Clinical Trials Database: one study, and WHO International Clinical Trial Registry: no studies). We identified an additional 32 studies on searching the reference lists of relevant studies. After removing duplicates, we screened a total of 204 studies, 155 of which we excluded as they did not focus on DMD or scoliosis surgery, or were narrative reviews. We examined the remaining 49 studies in detail but none of these satisfied the inclusion criteria. All of these studies were prospective or retrospective case series and were not clinical trials. Most of these studies also did not have a control group for comparison. Where a study did have a control group, the controls were patients who refused surgery or who were assigned a different treatment modality by the treating surgeons without randomization or quasi‐randomization. We therefore excluded these studies from further analyses because of a significant propensity for confounding and bias. The flow of studies is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Risk of bias in included studies

Not applicable.

Effects of interventions

No controlled trials met the inclusion criteria of the review for further analyses.

Discussion

Despite using a comprehensive search strategy for this review, we identified no randomized controlled trial of surgery for scoliosis in patients with DMD. Instead, we found many retrospective reviews or case series of patients with DMD and scoliosis treated with surgery. These studies showed varying results and had different conclusions. Although most agreed that surgery can improve patients' quality of life and functional status in terms of sitting posture, upper limb function, and ease of care, most failed to show a significant improvement in respiratory function or long‐term survival, and short‐ and long‐term postoperative complications were not uncommon.

However, a closer look at the relevant studies excluded may be helpful in guiding future clinical trials of scoliosis surgery for patients with DMD (Table 1). These 49 case series included 5 to 70 patients who had undergone scoliosis surgery. Eleven of these studies also included a comparison group of 21 to 115 patients without surgery (Alexander 2013; Eagle 2007; Galasko 1992; Galasko 1995; Kennedy 1995; Kinali 2006; Miller 1988; Miller 1991; Miller 1992; Sakai 1977; Suk 2014).

1. Characteristics of excluded studies.

| Study reference | Number of patients | Treatments | Outcome measures | Findings | Remarks |

| Alexander 2013 | 65 | Surgery (sublaminar wiring with Luque‐Galveston or supplemental pedicle screw fixation, or both) (28), no surgery (26) | Cobb angle, percentage of predicted FVC (%FVC), mortality | Mean correction of Cobb angle was 34.8º in the surgical group and mean deterioration was 16.1º in the non‐surgical group. There was no significant difference in the rate of decline in %FVC per year between surgical group (5.6% decline/year) and non‐surgical group (6.9% decline/year). There was no significant difference in the mean age of death between the 2 groups | |

| Alman 1999 | 48 | Spinal fusion to L5 (38) or spinal fusion to sacrum (10) using multiple‐level sublaminar wires with either a modified unit rod with Galveston extensions to the pelvis cut‐off, a modified rod with a cross‐link placed at the caudal end, or 2 Luque rods | Cobb angle, torso decompensation, sitting obliquity, spinal obliquity, need for revision surgery, mortality | Sitting obliquity and spinal obliquity increased in patients fused to L5. 2 patients had fracture of L5 lamina. 2 patients required revision surgery | |

| Arun 2010 | 43 | Sublaminar instrumentation (19) or hybrid sublaminar and pedicle screw (13) or pedical screw (11) | Cobb angle, flexibility index, blood loss, operating time, complications | Percentage correction of Cobb angle was 72.5 +/‐ 14.5% (Group A), 82 +/‐ 6% (Group B), and 82 +/‐ 8% (Group C). Flexibility indices were 60 +/‐ 6.33% (Group A), 70 +/‐ 4.65% (Group B), and 67 +/‐ 6.79% (Group C). Mean blood loss was 4.1 L (Group A), 3.2 L (Group B), and 2.5 L (Group C). Mean operating times were 300 min (Group A), 274 min (Group B), and 234 min (Group C). Complications: 3 wound infections and 2 implant failure (Group A), 1 implant failure (Group B), 1 wound infection and 1 partial screw pull‐out (Group C) | Concluded that pedicle screw system might be favored because of the lesser blood loss and surgical time |

| Bellen 1993 | 47 | Segmental spinal instrumentation according to Luque's technique | Mortality, complications | Many patients had general and pulmonary and mechanical complications | Concluded that a total spinal arthrodesis could probably be avoided in these patients, who often demonstrate a satisfying spontaneous fusion after instrumentation |

| Bentley 2001 | 101 (included 33 patients with SMA and 4 patients with congenital muscular dystrophy) | Modified Luque (87), Harrington‐Luque (14) | Cobb angle, pelvic obliquity, mortality, complications, patient satisfaction | Cobb angle decreased from 70º to 37º, pelvic obliquity decreased from 20º to 13º. Early severe complications in 10 patients, late complications in 24 patients. No perioperative mortality. Excellent satisfaction in 89.6% of patients | Incidence of minor or temporary complications was high, but occurred chiefly in patients with very severe curves and considerable pre‐existing immobility |

| Bridwell 1999 | 33 (included 21 patients with SMA) | Posterior segmental spinal instrumentation applied from the upper thoracic spine (T2, T3, T4, T5) down to L5 or the sacrum and pelvis. Early in the series, patients with DMD with smaller curves (< 40º) were fixed to L5. All had bilateral segmental fixation with Wisconsin or sublaminar wires at each level and at times with hook supplementation. All patients fused to the sacrum had Galveston or Galveston‐like fixation | Questionnaires to evaluate function, self image, cosmesis, pain, pulmonary status, patient care, quality of life, satisfaction, radiographic data | All patients seemed to have benefited from the surgery. Cosmesis, quality of life, and overall satisfaction rated the highest | |

| Brook 1996 | 17 | L‐rod instrumentation (10), distal instrumentation with Galveston construct and rigid cross‐linking (7) | Cobb angle and pelvic obliquity, percentage of predicted FVC (%FVC), mortality, complications | Correction of Cobb angle better in the Galveston group (63% versus 51%). No pseudoarthroses or instrument failures in the Galveston group. In total 4 patients had FVC < 25%, 2 required ventilation postoperatively. No other respiratory complications. No perioperative mortality | The effect of surgery on respiratory function remains uncertain |

| Cambridge 1987 | 14 | Segmental spinal instrumentation (13), Harrington distraction rods (1) | Mortality, complications, sitting tolerance | No perioperative mortality, 1 patient required repeated re‐intubation. All patients achieved excellent long‐term sitting tolerance | Recommended posterior spinal fusion with segmental instrumentation when scoliosis > 30º. Spinal fusion did not increase life expectancy or pulmonary function |

| Cervellati 2004 | 20 | Modified Luque technique (19) or Cotrel‐Dubousset instrumentation (1) | Cobb angle, vital capacity, mortality | Mean correction of Cobb angle at follow‐up was 28º. Mean loss of correction was 6º. Vital capacity showed a slow progression, slightly inferior to its natural evolution in untreated patients. Death in 1 patient | |

| Chataigner 1998 | 27 | Sublaminar wiring with Luque rods (5) or Hartshill rectangle (22). Sacral fixation with ilio‐sacral screws linked to the rectangle by Cotrel‐Dubousset rods and dominos (15) | Cobb angle, pelvic obliquity, coronal imbalance, sagittal imbalance, vital capacity, mortality, complications | Scoliosis reduced to 10º after surgery and 13º after 30 months' follow‐up. Pelvic obliquity was reduced to 4º after surgery and 7º after 30 months. A good spinal balance was present in 20 patients after surgery. A coronal or sagittal imbalance averaging 40 mm was observed in 22 patients at follow‐up. Vital capacity had annual decrease of 6.4%. 17 patients were alive with a 50 months' follow‐up. No operative mortality. 1 patient required tracheostomy postoperatively | Concluded that surgery did not result in respiratory improvement or in life duration lengthening |

| Dubousset 1983 | 37 | Luque rods, Harrington rods, segmental instrumentation | Cobb angle, vital capacity, mortality | Scoliosis reduced from 80º to 24º. No effect on decline of vital capacity. No clear benefit in length of survival | |

| Eagle 2007 | 75 | Surgery and nocturnal ventilation (27), nocturnal ventilation only (13), no surgery or ventilation (35) | Survival, complications, FVC | No perioperative deaths. Complications: gastrointestinal bleeding (2), postoperative ileus (1), spinal infection requiring removal of surgical rods (1), pressure sores (1), chronic pain due to prominence of metal prosthesis (2). Mean FVC reduced significantly (mean 1.4 L to 1.13 L) after 1 year. Median survival longer in surgery with ventilation group compared to ventilation alone (30 versus 22.2 years). Survival at 24 years higher in surgery with ventilation group compared to ventilation or no intervention (84% versus 34.6% versus 10.7%) | Spinal surgery did not improve FVC. Combined surgery and nocturnal ventilation improved survival |

| Gaine 2004 | 74 | Luque rod (55), Isola pedicle screw (19) | Cobb angle, pelvic obliquity, mortality, complications | Fusion to S1 did not offer benefit over fusion to more proximal level. Isola system appears to maintain a slightly better Cobb angle. 1 perioperative mortality due to cardiorespiratory failure. Complications: failure of implants (3), wound infection (2), pseudarthrosis (2), metal implant prominence requiring removal (1) | |

| Galasko 1992 | 55 | Surgery (32), refused surgery (23) | Mortality, complications, FVC, PEFR, Cobb angle | In surgery group, FVC static for 3 years then slightly decreased. Improved PEFR maintained for up to 5 years. Cobb angle improved from 47º to 34º at 5 years. Slightly improved survival with surgery. Complications: respiratory failure requiring tracheostomy (1), pneumonia (1), heart block (1), superficial wound infection (1) | |

| Galasko 1995 | 76 | Surgery (48), refused surgery (28) | Mortality, complications, FVC, PEFR, Cobb angle | No pseudarthrosis or postoperative failures. Annual decrease of FVC lower in surgery group (0.07 versus 0.15). PEFR increased annually by 7.6 L/min in surgery group but decreased annually by 7.6 L/min in non‐surgery group. Cobb angle after 3 years better in surgery group (34º versus 93º). At 5 years, survival higher in surgery group (61% versus 23%). Complications: respiratory failure requiring tracheostomy (1) | Patients with surgery had better lung function and improved survival |

| Gayet 1999 | 37 | Pedicular screwing system in the lumbo‐sacral area and transversal attachments with steel threads at the thoracic level. A sublaminar fastening was placed at L1 | Vital capacity, mortality, complications, Cobb angle, pelvic obliquity | Cobb angle decreased from 19º to 5.2º, and 9.5% at the latest measurement. Pelvic balancing was corrected and results have held over time. Vital capacity was reduced by 3.6% per year. Complications: stem rupture (1), superficial infection (4) | Cardiorespiratory function and life expectancy were not improved, but most patients and families were very satisfied by the comfort brought about by the surgical operation |

| Granata 1996 | 30 | Segmental spinal instrumentation and fusion | Cobb angle, mortality, complications, vital capacity, quality of life, sitting position, esthetic improvement | 29 patients had a mean 59% correction of scoliosis. Very limited loss of correction over time. One died after cardiac arrest. Complications: pressure sore (1), metal prominence requiring trimming (1). Mean vital capacity decreased from 57 +/‐ 17% to 34 +/‐ 13% at 3.9 +/‐ 2 years after surgery. The majority of the patients and their parents evaluated sitting position, esthetic improvement, and quality of life positively | |

| Hahn 2008 | 20 | Spinal fixation with pedicle‐screw‐alone constructs | Percentage of predicted FVC (%FVC), Cobb angle, degree of pelvic tilt, lumbar lordosis and thoracic kyphosis, mortality, complications | Cobb angle improved from 44º to 10º, pelvic tilt improved from 14º to 3º. Lumbar lordosis improved from 20º to 49º, thoracic kyphosis remained unchanged. No problems related to iliac fixation, no pseudarthrosis or implant failures. No pulmonary complications. %FVC decreased from 55% preoperatively to 44% at the last follow‐up. 1 patient died intraoperatively due to a sudden cardiac arrest | The rigid primary stability with pedicle screws allowed for early mobilization of the patients,which helped in avoiding pulmonary complications |

| Harper 2004 | 45 | AO Universal Spinal System inserted through a posterior approach | Mortality, complications, hospital stay | No significant difference in operative and postoperative outcomes between patients with preoperative FVC > 30% and ≤ 30%. Complications in 9 patients: pneumonia, respiratory failure requiring tracheostomy, ARDS, pleural effusion, cardiac arrhythmia | Concluded that routine postoperative use of mask ventilation to facilitate early tracheal extubation was vital |

| Heller 2001 | 31 | Isola system | Cobb angle, pelvic obliquity, mortality, complications | Cobb angle decreased from 48.6º to 12.5º, pelvic obliquity decreased from 18.2º to 3.8º. 1 postoperative death due to cardiac failure. Complications: pneumonia (1), respiratory arrest (1), pneumothorax (1), respiratory failure requiring tracheostomy (1), dislocation of hook (2), infection requiring revision surgery (5), iliac vein thrombosis (1), massive bleeding (1) | |

| Hopf 1994 | 20 | Multi‐segmental instrumentation | Mortality, complications, Cobb angle | Mean Cobb angle decreased from 70.6º to 31.2º (mean correction 39.4º or 55.8%). Lordosis of the lumbar spine corrected from 4.1º to 17.8º. No perioperative mortality. Complication: bladder dysfunction in 1 patient | Recommended using multi‐segmental instrumentation methods to enable rapid mobilization and a postoperative care without brace or cast |

| Kennedy 1995 | 38 | Surgery (17), no surgery (21) | Cobb angle, FVC, mortality | Mean Cobb angle of the surgical group at 14.9 years was 57 +/‐ 16.4º, and of the non‐surgical group at 15 years was 45 +/‐ 9.9º. No difference in the rate of deterioration of %FVC, which was 3% to 5% per year. No difference in survival between groups | Spinal stabilization in DMD did not alter the decline in pulmonary function or improve survival |

| Kinali 2006 | 123 | Surgery (43), no surgery (80) | Survival, FVC, sitting comfort | No difference in survival, respiratory impairment, or sitting comfort between patients managed conservatively and those who had surgery | |

| Laprade 1992 | 9 | Sublaminar wiring (4), intraspinous segmental wiring (5) | Mortality, complications, operative time, blood loss, Cobb angle | Operative time and blood loss lower in sublaminar compared to intraspinous wiring. Allogeneic bone grafts to supplement the autogenous bone graft allowed for extensive fusion. Cobb angle decreased by a mean of 32º. Complications: dural leak (1), transient numbness of left foot (1), dislodgement of sacral alar hooks (2). | Recommended segmental fusion and allogeneic bone grafts |

| Marchesi 1997 | 25 | Modified Luque: sacral screws in each S‐1 pedicle and a device for transverse traction between the caudal right‐angle bends of the L‐rods | Cobb angle, pelvic obliquity, mortality, instrumental failure, sitting balance | Cobb angle decreased from 68º to 18º, pelvic obliquity decreased from 21º to < 15º with mean correction of 75%. No instrumentation failure or loss of correction > 3º. A good sitting balance could be restored in every patient. No perioperative mortality | |

| Marsh 2003 | 30 | Posterior spinal fusion | Cobb angle, mortality, complications, hospital stay | Mean correction of Cobb angle 36º. 2 subgroups of patients were compared: those with more than 30% preoperative FVC (17 patients) and those with less than 30% preoperative FVC (13 patients). There were 9 complications in total, with 1 patient in each group requiring a temporary tracheostomy. The postoperative stay for patients in each group was similar (24 days in the > 30% group, 20 days in the < 30% group), and the complication rate was comparable with other published series. No perioperative mortality | Concluded that spinal fusion could be offered to patients with DMD even in the presence of a low FVC |

| Matsumura 1997 | 8 | Luque rod (2), Cotrel‐Dubousset rod (6) | Cobb angle, FVC, quality of life, mortality, complications, sitting balance | Cobb angle corrected from 58.8º to 28.6º with a mean corrective rate of 51.3%. FVC increased in 3 patients with moderate scoliosis (Cobb angle: 50º to 80º). 2 cases with low %FVC (16.9% and 30.4%, respectively) had poor prognosis in respiratory status. 1 died of pneumonia at 17 months after surgery, and the other required mechanical ventilation. Sitting balance improved in all patients | Recommended spinal fusion for patients with Cobb angle more than 30º and with %FVC more than 35%. Although the impact of spinal fusion upon life expectancy remained unclear, favorable effects on respiratory function and quality of life could be expected for carefully selected patients with DMD |

| Mehdian 1989 | 17 | Luque rods secured by conventional sublaminar wires (9), Luque rods secured by sublaminar nylon straps (4), 2 L‐shaped rods connected by H‐bars secured by closed wire loops (3), Hartshill rectangle and sublaminar wires (1) | Cobb angle, respiratory function | Significant loss of correction in Luque rods secured by sublaminar nylon straps and Hartshill system Strong correlation between advance of scoliosis and respiratory function | |

| Miller 1988 | 67 | Surgery (21), no surgery (46) | FVC | No difference was found in the rate of deterioration of the percentage of normal FVC | |

| Miller 1991 | 39 | Surgery (17), no surgery (22) | Respiratory function, sitting comfort, sitting appearance | No significant differences in terms of declining respiratory function. All operated patients reported either improved sitting comfort, appearance, or both | Concluded distinct benefits from segmental spine fusion; however, no salutary effect upon respiratory function either in the short term or after up to 5 years' follow‐up |

| Miller 1992 | 183 (87 followed up to death) | Surgery (68), no surgery (115) | Survival, patient comfort, ease of care, respiratory function, quality of life | Patients with surgery were more comfortable in the later years of life and easier to care for, but spinal fusion did not affect deteriorating pulmonary function. Age at death for the 29 boys who underwent spinal fusion was 18.3 years, similar to that of the 58 boys without surgery. Factors that improved the patients' quality of life included segmental instrumentation, fusion from T2 to the pelvis, correcting or balancing scoliosis, creating normal sagittal plane alignment, and correcting pelvic obliquity | |

| Modi 2008a | 26 (including 7 cerebral palsy, 5 SMA, 4 others) | posterior pelvic screw fixation | Cobb angle, pelvic obliquity, complications | Mean Cobb angle: 78.53º (before surgery), 30.7º (after surgery), 33.06º (final follow‐up). There was no difference in the percentage correction between the group with > 90º and the group with < 90º. Complications: 1 transient loss of lower limb power, 1 deep wound infection | |

| Modi 2008b | 24 patients (including 6 cerebral palsy, 5 SMA, 4 others) and 12 controls (adolescent idiopathic scoliosis) | Posterior pedicle screw | Cobb angle, pelvic obliquity, apical rotation | Mean Cobb angle decreased from 74º to 32º. Mean pelvic obliquity decreased from 14º to 6º. Mean apical rotation decreased from 42º to 33º. There was no significant difference between different patient groups or between patients and controls | |

| Modi 2009 | 50 (including 18 patients with cerebral palsy, 8 with SMA, and 6 others) | Posterior spinal fusion with segmental spinal instrumentation using pedicle screw fixation | Mortality, complications, Cobb angle, pelvic obliquity | Cobb angle decreased from 79.3 +/‐ 30.3º to 31.3 +/‐ 21.6º. Pelvic obliquity decreased from 14.6 +/‐ 9.4º to 6.8 +/‐ 6.3º. 2 deaths (1 due to cardiac arrest, 1 due to hypovolemic shock. 34 patients had at least 1 perioperative complication (16 pulmonary, 14 abdominal, 3 wound related, 2 neurological, 1 cardiovascular). Postoperative complications: 7 coccygodynia, 3 screw head prominence, 2 bedsore, 1 implant loosening | DMD patients had higher risk of postoperative coccygodynia |

| Modi 2010 | 55 (including 28 patients with cerebral palsy and 10 with SMA) | Spinal fixation from T2/T3/T4 to L4/L5 with or without pelvic fixation. Group 1: pelvic obliquity > 15º with pelvic fixation; group 2: pelvic obliquity > 15º without pelvic fixation; group 3: pelvic obliquity < 15º without pelvic fixation | Cobb angle, pelvic obliquity, complications | Mean correction of Cobb angle after operation: group 1: 43.8º; group 2: 40º; group 3: 48.7º. Mean loss of correction of Cobb angle at last follow‐up: group 1: 0.6º; group 2: 2.3º; group 3: 3º. Mean correction of pelvic obliquity: group 1: 14.4º; group 2: 10.7º; group 3: 5º. Mean loss of correction of pelvic obliquity at last follow‐up: group 1: ‐0.6º; group 2: 6.5º; group 3: 0.8º. Group 2 showed significant loss of pelvic obliquity compared to group 1. Complications: 3 patients in group 1 had sacral sores | Patients who have pelvic obliquity > 15º require pelvic fixation to maintain correction |

| Mubarak 1993 | 22 | Luque segmental instrumentation and fusion instrumented to the sacropelvis (12), instrumented to L5 (10) | Cobb angle, pelvic obliquity | Outcomes similar between the 2 groups | Concluded that if treatment is initiated early, Luque instrumentation and fusion from high thoracic (T2 or T3) to the 5th lumbar vertebra should be sufficient |

| Nakazawa 2010 | 36 | Autogenous bone graft (20), allogeneic bone graft (16) | Cobb angle, operating time, blood loss | No difference in Cobb angle between the 2 groups. Mean operating time longer in autogenous group (253 min) compared to allogenous group (233 min). Mean blood loss higher in autogenous group (850 ml) compared to allogenous group (775 ml) | 90% and 50% of patients in autogenous group reported donor site pain after 1 week and 3 months, respectively. Concluded against autogenous bone graft for scoliosis surgery in DMD patients |

| Rice 1998 | 19 | Long spinal fusion to L5 and ongoing wheelchair seating attention | Sitting position | At long‐term follow‐up, 15 patients continued to sit in a well‐balanced position | Concluded that surgical fusion of the spine to L5 combined with ongoing attention to seating was associated with good long‐term functional results in these patients |

| Rideau 1984 | 5 | Luque segmental spinal stabilisation without bone fusion | Cobb angle, vital capacity, mortality, complications, hospital stay, pelvic obliquity, patient comfort | Cobb angle decreased from 27º to 11º. Pelvic obliquity partially reduced. Static vital capacity after 2 years. No perioperative mortality, 1 bronchopneumonia. All patients more comfortable during wheelchair activities | Concluded that surgical intervention should be undertaken prophylactically when there is high risk of a rapidly evolving curve with a severe restrictive lung syndrome |

| Sakai 1977 | 41 | Surgery (10), no surgery (31) | Sitting stability, mortality, complications | Pulmonary complications were minimized by performing preoperative tracheotomy on all patients who had vital capacities less than 40% or non‐functional coughs, or both. No perioperative mortality. Spinal fusion permitted long‐term sitting stability despite the progression of the disease | |

| Sengupta 2002 | 50 | Pelvic fixation: Galveston technique (9), L‐rod (22) Lumbar fixation: pedicle screw + sublaminar wires (19) |

Cobb angle, pelvic obliquity, mortality, complications, hospital stay | In the pelvic fixation group, the mean Cobb angle and pelvic obliquity were 48º and 19.8º at the time of surgery, 16.7º and 7.2º immediately after surgery, and 22º and 11.6º at the final follow‐up (mean 4.6 years). The mean hospital stay was 17 days. 5 major complications: deep wound infection (1), revision of instrumentation prominence at the proximal end (2), loosening of pelvic fixation (2). In the lumbar fixation group, the mean Cobb angle and pelvic obliquity were 19.8º and 9º at the time of surgery, 3.2º and 2.2º immediately after surgery, and 5.2º and 2.9º at the final follow‐up (mean 3.5 years). The mean hospital stay (7.7 days) was much less compared with the pelvic fixation group. Pelvic obliquity was corrected and maintained below 10º in all but 2 cases, who had an initial pelvic obliquity exceeding 20º. 2 complications: instrumentation failure at the proximal end (1), deep wound infection (1). No perioperative mortality | |

| Shapiro 1992 | 27 | Harrington rod (2), Harrington rod with sublaminar wires (7), Harrington rod, Luque rod, and 2 double sublaminar wires at each level (17) | Cobb angle, FVC, mortality, complications | 1 sudden cardiac arrest and died intraoperatively. 3 intraoperative complications reversed without sequelae. Mean postoperative correction 13.1 +/‐ 11.9º, with mean loss of correction 5.1 +/‐ 3.1º at 2.4 +/‐ 1.8 years. Mean FVC preoperatively was 45.3 +/‐ 15.9% with continuing diminution to 28.7 +/‐ 14.9% at 3.3 +/‐ 2.2 years after surgery | Concluded that the main benefit of surgical stabilisation was the relative ease and comfort of wheelchair seating compared with those non‐operated patients who developed progressive deformity. No lasting improvement or stabilisation in FVC following surgery as decreasing function was related primarily to muscle weakness |

| Stricker 1996 | 46 (included other neuromuscular diseases) | Modified Luque technique | Cobb angle, complications | Cobb angle decreased from 63º to 24º (correction of about 62%). Failure of implants, pseudarthroses, and major losses of correction in purely neuromuscular scolioses could be avoided by using rigid segmental fixation and a dorsolateral fusion with a mixture of autologous and allogenous bone | Concluded that the best method of treatment in DMD is surgery performed as early as possible, i.e. at the time of loss of walking capacity in the case of a scoliosis exceeding 20º and with 2 consecutive X‐rays proving curve progression |

| Suk 2014 | 66 | Surgery (40), refused surgery (26) | Cobb angle, lordosis angle, pelvic obliquity, FVC, end‐tidal CO2, use of NIPPV, functional status (assessed by manual muscle test, modified Rancho Scale, and MDSQ) | Significantly better mean Cobb angle in the surgical group (36.2 +/‐ 16.1º) compared with the non‐surgical group (106.1 +/‐ 122.3º). Significantly worse mean lordosis angle in the surgical group (37.9 +/‐ 18.2º) compared with the non‐surgical group (18.4 +/‐ 34.3º). Significantly better mean pelvic obliquity in the surgical group (11.4 +/‐ 8.7º) compared with the non‐surgical group (29.0 +/‐ 15.5º). No significant difference in mean manual muscle test score between the surgical group (23.2 +/‐ 8.3) and the non‐surgical group (22.8 +/‐ 6.3). No significant difference in mean modified Rancho Scale between the surgical group (3.9 +/‐ 0.3) and the non‐surgical group (4.04 +/‐ 0.3). Significantly higher mean MDSQ score in the surgical group (35.1 +/‐ 14.7) compared with the non‐surgical group (26.9 +/‐ 9.9). Significantly lower mean deterioration in FVC after 2 years in the surgical group (268 +/‐ 361 ml) compared with the non‐surgical group (536 +/‐ 323 ml). No significant difference in mean pCO2 between the surgical group (38.4 +/‐ 5.5 mmHg) and the non‐surgical group (39.4 +/‐ 6.7 mmHg). No significant difference in the use of NIPPV between the surgical group (80%) and the non‐surgical group (88%) | |

| Sussman 1984 | 11 | Harrington instrumentation (group 1) (3), Luque instrumentation (group 2) (3), segmental spinal instrumentation with fusion (group 3) (5) | Complications, Cobb angle, hospital stay | Mean Cobb angle correction: group 1: 40%; group 2: 35%; group 3: 60%. When surgery to stabilize spinal deformity is done in younger patients in whom pulmonary function is better and curves are milder, complication rate and length of hospital stay are diminished, correction and balance are improved, and patients rapidly return to their normal lifestyle | Concluded that segmental spinal instrumentation had advantage of allowing rapid mobilization without need of a cast or body jacket. Recommended stabilization of the collapsing spine surgically with segmental instrumentation and fusion when scoliosis reached 30º to 40º |

| Takaso 2010 | 20 | Segmental pedicle screws instrumentation and fusion to L5 | Cobb angle, pelvic obliquity, operating time, blood loss, complications | Mean Cobb angle decreased from 70º to 15º. Mean pelvic obliquity decreased from 13º to 6º. Mean intraoperative blood loss was 890 ml (range: 660 to 1260 ml). Mean total blood loss was 2100 ml (range: 1250 to 2880 ml). No major complications | |

| Thacker 2002 | 24, of whom 5 had DMD | Not detailed in DMD patients | FEV1, FVC, mortality, complications | FVC and FEV1 maintained, pseudarthrosis in 1 patient, no perioperative mortality | Included 7 SMA, 6 spastic cerebral palsy, 3 congenital myopathy, 2 spina bifida, 1 paraspinal neuroblastoma in the series |

| Velasco 2007 | 56 | Posterior spinal fusion | Percent normal FVC | The rates of FVC decline were 4% per year presurgery, which decreased to 1.75% per year postsurgery | |

| Weimann 1983 | 24 | Long Harrington instrumentations and spinal fusions from S1 up to the upper thoracic spine (T4, 5, or 6) | Mortality, complications | 1 patient died 2 years after his operation from dystrophic cardiomyopathy | Concluded that prophylactic spinal fusion deserved consideration for these patients |

ARDS: adult respiratory distress syndrome; DMD: Duchenne muscular dystrophy; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC: forced vital capacity; MDSQ: Muscular Dystrophy Spine Questionnaire; NIPPV: non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation; PEFR: peak expiratory flow rate; SMA: spinal muscular atrophy

Outcome measures and comparisons

The studies had different objectives and focused on different outcomes. Most studies aimed to investigate whether spinal surgery improves the degree of scoliosis in the short term (immediate postoperative period) and in the long term (years later). Most studies used Cobb angle and degree of pelvic obliquity as outcome measures and described early and late complications of surgery. Some studies also reported degree of lumbar lordosis (Suk 2014), duration of hospitalization (Harper 2004; Rideau 1984; Sengupta 2002; Sussman 1984), perioperative mortality (Alman 1999; Bentley 2001; Brook 1996; Cambridge 1987; Cervellati 2004; Chataigner 1998; Dubousset 1983; Eagle 2007; Gaine 2004; Galasko 1992; Galasko 1995; Gayet 1999; Granata 1996; Hahn 2008; Harper 2004; Heller 2001; Hopf 1994; Kennedy 1995; LaPrade 1992; Marchesi 1997; Marsh 2003; Matsumura 1997; Modi 2009; Rideau 1984; Sakai 1977; Sengupta 2002; Shapiro 1992; Thacker 2002; Weimann 1983), and length of survival (Alexander 2013; Eagle 2007; Kinali 2006; Miller 1992). Many studies reported the change in respiratory function after operation (Alexander 2013; Brook 1996; Cervellati 2004; Chataigner 1998; Dubousset 1983; Eagle 2007; Galasko 1992; Galasko 1995; Gayet 1999; Granata 1996; Kennedy 1995; Kinali 2006; Matsumura 1997; Mehdian 1989; Miller 1988; Miller 1991; Miller 1992; Rideau 1984; Shapiro 1992; Suk 2014; Thacker 2002; Velasco 2007). The parameters used included vital capacity or forced vital capacity, peak expiratory flow rate, and forced expiratory volume in one second. A few studies also reported patient oriented subjective outcomes such as quality of life, functional status, self image, cosmetic appearance, pain, and patient satisfaction (Bentley 2001; Bridwell 1999; Granata 1996; Matsumura 1997; Miller 1991; Miller 1992; Rideau 1984; Suk 2014). While most studies evaluated the outcomes of spinal surgery in general, some studies attempted to compare different surgical techniques, such as Luque instrumentation versus Isola pedicle screw (Gaine 2004), sublaminar wiring versus intraspinous segmental wiring (LaPrade 1992), Luque instrumentation versus distal instrumentation with Galveston construct and rigid cross‐linking (Brook 1996), Harrington‐Luque instrumentation versus modified Luque instrumentation (Bentley 2001), Harrington instrumentation versus Luque instrumentation versus segmental spinal instrumentation with fusion (Sussman 1984), sublaminar instrumentation versus pedicle screw versus a hybrid system (Arun 2010), or autogenous versus allogenous bone graft (Nakazawa 2010). Some studies also compared the outcomes of spinal fusion to different extents (Alman 1999; Bridwell 1999; Gaine 2004; Mubarak 1993; Sengupta 2002; Modi 2010), such as fusion to L5 versus fusion to sacrum. Some studies compared surgical outcomes in patients with different preoperative respiratory function (Harper 2004; Marsh 2003; Matsumura 1997; Sussman 1984).

Outcomes on survival

Most studies did not demonstrate obvious benefits of scoliosis surgery in terms of prolonging survival (Alexander 2013; Brook 1996; Cervellati 2004; Chataigner 1998; Gayet 1999; Granata 1996; Hahn 2008; Kennedy 1995; Kinali 2006; Mehdian 1989; Miller 1988; Miller 1991; Miller 1992; Shapiro 1992; Thacker 2002). One study showed that when spinal surgery was combined with nocturnal ventilation, patients had a longer median survival (30 years) compared with patients on nocturnal ventilation alone (22.2 years) (Eagle 2007). Another study showed that survival rate was higher at five years after surgery (61%) compared to those who refused surgery (23%) (Galasko 1995). In general, the age of death in patients with or without surgery was highly variable in the case series. Although most deaths could be attributed to respiratory infection, respiratory failure, progressive cardiomyopathy, and sudden cardiac death, in many cases the cause of death could not be ascertained. However, the age and causes of death did not seem to differ between patients with or without surgery. Perioperative mortality is generally uncommon. Most studies reported no perioperative mortality (Alman 1999; Bellen 1993; Bentley 2001; Bridwell 1999; Brook 1996; Cambridge 1987; Chataigner 1998; Dubousset 1983; Eagle 2007; Galasko 1992; Galasko 1995; Gayet 1999; Hopf 1994; Kennedy 1995; Kinali 2006; LaPrade 1992; Marchesi 1997; Marsh 2003; Matsumura 1997; Mehdian 1989; Miller 1992; Mubarak 1993; Nakazawa 2010; Rice 1998; Rideau 1984; Sakai 1977; Sengupta 2002; Stricker 1996; Sussman 1984; Takaso 2010; Thacker 2002; Weimann 1983), while some studies reported perioperative mortality ranging from 1.4% to 5% (Modi 2009; Gaine 2004; Cervellati 2004; Granata 1996; Hahn 2008; Harper 2004; Heller 2001; Shapiro 1992).

Outcomes on respiratory function

Galasko found that forced vital capacity could be stabilized for three years and peak expiratory flow rate maintained for up to five years after spinal fusion (Galasko 1992; Galasko 1995). Rideau also found that vital capacity could be maintained static for two years (Rideau 1984), and three patients in Matsumura's study had increased forced vital capacity after operation (Matsumura 1997). Velasco found that the average rate of decline of forced vital capacity dropped from 4% per year to 1.75% per year after surgery (Velasco 2007). Suk found that deterioration in forced vital capacity was better in patients who had received spinal surgery compared with those who had not, but there was no significant difference in end‐tidal CO2 or use of non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation (Suk 2014). On the other hand, most studies did not demonstrate obvious benefits of scoliosis surgery in terms of respiratory function (Alexander 2013; Brook 1996; Chataigner 1998; Cervellati 2004; Eagle 2007; Gayet 1999; Granata 1996; Hahn 2008; Kennedy 1995; Kinali 2006; Mehdian 1989; Miller 1988; Miller 1991; Miller 1992; Shapiro 1992; Thacker 2002). While some studies found that patients with poor preoperative respiratory function fared similarly to those with better respiratory function (Marsh 2003; Harper 2004), other studies suggested that the prognosis was worse in patients with poorer preoperative respiratory function (Matsumura 1997; Sussman 1984).

Functional outcome and quality of life

In general, previous descriptive studies suggested that surgical correction of scoliosis resulted in better sitting position, functional status, quality of life, and patient satisfaction (Bentley 2001; Bridwell 1999; Cambridge 1987; Granata 1996; Marchesi 1997; Matsumura 1997; Miller 1991; Miller 1992; Rice 1998; Rideau 1984; Sakai 1977; Shapiro 1992; Suk 2014).

Complications of spinal surgery

Severe complications after spinal surgery are not infrequent and occur in up to 68% of patients (Modi 2009). These include cardiac arrest (Bentley 2001), cardiac arrhythmia (Harper 2004), heart block (Galasko 1992), respiratory failure requiring tracheostomy (Chataigner 1998; Galasko 1992; Galasko 1995; Harper 2004; Heller 2001; Marsh 2003) or mechanical ventilation postoperatively (Bentley 2001; Brook 1996; Heller 2001; Modi 2009), massive bleeding (Heller 2001; Modi 2008a), pneumonia (Bentley 2001; Galasko 1992; Harper 2004; Heller 2001; Modi 2009; Rideau 1984), pleural effusion (Harper 2004; Modi 2009), hemothorax or pneumothorax (Bentley 2001; Heller 2001; Modi 2009), spinal cord injury (Modi 2009), colonic perforation (Bentley 2001), bladder dysfunction (Bentley 2001; Hopf 1994), urinary tract infection (Modi 2009), deep wound infection (Arun 2010; Modi 2008a; Modi 2009; Sengupta 2002), infection necessitating removal or revision of surgical implants (Eagle 2007; Heller 2001), failure of implants (Arun 2010; Bentley 2001; Gaine 2004; Stricker 1996), dislodgement or dislocation of implants (Heller 2001; LaPrade 1992; Matsumura 1997), loosening of implants (Arun 2010; Modi 2009; Sengupta 2002), mechanical problems requiring revision surgery (Bentley 2001; Gaine 2004; Gayet 1999; Granata 1996; Sengupta 2002), pseudarthrosis (Gaine 2004; Thacker 2002), bone fracture (Alman 1999), pressure sores (Granata 1996; Modi 2009; Modi 2010), dural leak (LaPrade 1992), and deep vein thrombosis (Heller 2001). Several studies reported that postoperative complications were more frequent in patients with greater severity of scoliosis (Bentley 2001; Sakai 1977; Sussman 1984).

Comparisons of different operative methods

In general, fusion to sacrum does not offer benefits over fusion to a more proximal level (Gaine 2004; Mubarak 1993; Rice 1998; Sengupta 2002), unless scoliosis is severe and pelvic obliquity is significant (Alman 1999; LaPrade 1992; Modi 2010). Although none of the surgical methods was uniformly better than others, Isola system, in Gaine 2004, or segmental spinal fusion, in Miller 1991 and Miller 1992, might achieve better correction of deformity, and intraspinous wiring might result in shorter operative time and less blood loss compared to sublaminar wiring (LaPrade 1992). Pedicle screw system might also result in shorter operative time and less blood loss compared to sublaminar instrumentation system (Arun 2010).

We performed no meta‐analysis of these available data because the retrospective, non‐randomized, uncontrolled studies were observational in nature and were prone to bias and confounding. Currently there is an absence of high‐level evidence supporting the use of scoliosis surgery in patients with DMD. There is also a lack of evidence for or against a particular modality of surgical approach. Controlled clinical trials with random allocation into treatment and control groups are needed before firm conclusions on the benefits and risks of scoliosis surgery in a patient with DMD can be made.

In the absence of evidence, it is our view that clinicians may need to consider anecdotal evidence and their personal experience as well as expert opinions as guidance for their decision on the best care for an individual patient. Potential benefits to quality of life and functional status as well as risks of morbidity and mortality should be fully discussed with patients before surgery for scoliosis is embarked upon. Patients should also be informed about the uncertainty of benefits on long‐term survival and respiratory function after scoliosis surgery.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Since no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were available to evaluate the effectiveness of scoliosis surgery in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, we can make no good evidence‐based conclusion to inform clinical practice.

Implications for research.

RCTs are needed to investigate the effectiveness of scoliosis surgery, in terms of patient satisfaction, quality of life, functional status, respiratory function (forced vital capacity, forced expiratory volume in one second, peak expiratory flow), and survival. It should be feasible to randomize patients into surgery versus non‐surgical management. Although placebo control treatment might not be feasible, random allocation of patients into different treatment groups is essential to avoid selection bias and ensure baseline comparability of different groups. Although blinding of patients and clinicians is almost impossible, blinding of outcome assessors is important and probably feasible. Quality of life and functional status should be assessed by validated questionnaires and instruments. RCTs should also investigate the relative benefits and risks of different surgical treatment modalities and different extents of spinal fusion. Stratifications by potentially important prognostic factors such as age, baseline respiratory function, and severity of scoliosis should be considered.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 February 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Searches updated and results incorporated. |

| 5 January 2015 | New search has been performed | Review updated with search update to 16 June 2015. Two excluded studies added. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2005 Review first published: Issue 1, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 January 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Review updated with search update to July 31 2012 but no new studies found. Two of the original authors withdrawn. |

| 7 November 2012 | New search has been performed | Two studies added to excluded studies tables. Minor editorial revisions. |

| 22 August 2010 | New search has been performed | Review updated with search update but no new studies found. |

| 13 May 2009 | Amended | Acknowledgement added. |

| 2 October 2008 | New search has been performed | Updated review. |

| 23 October 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment. |

Notes

New evidence on this topic is slow to emerge. The next update is planned in 2019, although an earlier update will be considered if studies eligible for inclusion are performed in the interim.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Sarah Massey and the Illingworth Library at the Sheffield Children's Hospital for their help and support in locating and retrieving studies. We also thank Angela Gunn for updating search strategies and searching various electronic databases. Editorial support from the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group for an earlier update was funded by the TREAT NMD Network European Union Grant 036825.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, National Institute for Health Research, National Health Service, or the Department of Health. The Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group is also supported by the MRC Centre for Neuromuscular Disease.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE strategy

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to June Week 1 2015> Search Strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 randomized controlled trial.pt. (396862) 2 controlled clinical trial.pt. (89648) 3 randomized.ab. (293733) 4 placebo.ab. (152857) 5 drug therapy.fs. (1782093) 6 randomly.ab. (207091) 7 trial.ab. (303153) 8 groups.ab. (1318490) 9 or/1‐8 (3363492) 10 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (4057817) 11 9 not 10 (2863375) 12 surg$.mp. or surgery/ (1563766) 13 spine$.mp. (98598) 14 spinal.mp. (299674) 15 vertebra$.mp. (190697) 16 or/13‐15 (465197) 17 12 and 16 (67662) 18 spinal fusion/ or spinal fusion.mp. (18917) 19 17 or 18 (74660) 20 scolio$.mp. or Scoliosis/ (17344) 21 duchenne.mp. or Muscular Dystrophy, Duchenne/ (8935) 22 11 and 19 and 20 and 21 (23) 23 remove duplicates from 22 (22)

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

Database: Embase <1980 to 2015 Week 24> Search Strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 crossover‐procedure.sh. (43171) 2 double‐blind procedure.sh. (121038) 3 single‐blind procedure.sh. (20388) 4 randomized controlled trial.sh. (373903) 5 (random$ or crossover$ or cross over$ or placebo$ or (doubl$ adj blind$) or allocat$).tw,ot. (1149602) 6 trial.ti. (178538) 7 clinical trial/ (845836) 8 or/1‐7 (1754858) 9 (animal/ or nonhuman/ or animal experiment/) and human/ (1373553) 10 animal/ or nonanimal/ or animal experiment/ (3397550) 11 10 not 9 (2826709) 12 8 not 11 (1647123) 13 limit 12 to embase (1348090) 14 Surgery/ or surg$.mp. (2399654) 15 (spine or spinal or vertebra$).mp. (561465) 16 14 and 15 (111605) 17 exp Spine Fusion/ (19893) 18 (spinal fusion or spine fusion).mp. (20513) 19 16 or 17 or 18 (117843) 20 exp Scoliosis/ or scoliosis.mp. (24702) 21 Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy/ or duchenne.mp. (13075) 22 13 and 19 and 20 and 21 (15)

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor General Surgery explode all trees #2 surgery #3 (#1 OR #2) #4 (spine or spinal or vertebra*) #5 (#3 AND #4) #6 MeSH descriptor Spinal Fusion, this term only #7 spinal fusion or spine fusion #8 (( #5 AND #6 ) OR #7) #9 scoliosis #10 duchenne #11(#8 AND #9 AND #10)

Appendix 4. CINAHL Plus search strategy

Tuesday, June 16, 2015 8:26:22 AM S31 S29 AND S30 0 S30 EM 20141107‐ 203,432 S29 S18 and S28 15 S28 S25 and S26 and S27 43 S27 ("scoliosis") or (MH "Scoliosis") 5,070 S26 ("duchenne") or (MH "Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy") 1,105 S25 S22 or S24 19,231 S24 S23 or spinal fusion or spine fusion 5,799 S23 (MH "Spinal Fusion") 5,389 S22 S20 and S21 18,557 S21 spine or spinal or vertebra* 70,805 S20 S19 or surgery 302,370 S19 (MH "Surgery, Operative") 18,029 S18 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 752,583 S17 ABAB design* 93 S16 TI random* or AB random* 151,010 S15 ( TI (cross?over or placebo* or control* or factorial or sham? or dummy) ) or ( AB (cross?over or placebo* or control* or factorial or sham? or dummy) ) 301,434 S14 ( TI (clin* or intervention* or compar* or experiment* or preventive or therapeutic) or AB (clin* or intervention* or compar* or experiment* or preventive or therapeutic) ) and ( TI (trial*) or AB (trial*) ) 105,987 S13 ( TI (meta?analys* or systematic review*) ) or ( AB (meta?analys* or systematic review*) ) 36,870 S12 ( TI (single* or doubl* or tripl* or trebl*) or AB (single* or doubl* or tripl* or trebl*) ) and ( TI (blind* or mask*) or AB (blind* or mask*) ) 23,445 S11 PT ("clinical trial" or "systematic review") 127,929 S10 (MH "Factorial Design") 945 S9 (MH "Concurrent Prospective Studies") or (MH "Prospective Studies") 264,883 S8 (MH "Meta Analysis") 22,461 S7 (MH "Solomon Four‐Group Design") or (MH "Static Group Comparison") 48 S6 (MH "Quasi‐Experimental Studies") 7,381 S5 (MH "Placebos") 9,272 S4 (MH "Double‐Blind Studies") or (MH "Triple‐Blind Studies") 31,799 S3 (MH "Clinical Trials+") 188,614 S2 (MH "Crossover Design") 13,034 S1 (MH "Random Assignment") or (MH "Random Sample") or (MH "Simple Random Sample") or (MH "Stratified Random Sample") or (MH "Systematic Random Sample") 69,594

Appendix 5. ProQuest Dissertation & Thesis database search strategy

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global

Your search for all(("spine fusion" OR "spinal fusion" OR (surgery NEAR/5 (spine OR vertebra*))) AND duchenne AND scoliosis AND (random* OR "double blind")) found 0 results.

Appendix 6. Clinical trial registry databases

Duchenne and surgery and scoliosis

Appendix 7. Additional methods

The following methods have been prespecified for use if studies eligible for inclusion are identified (Cheuk 2013).

Data extraction and management

We planned that two review authors (DC and VW) would independently extract data from included trials and enter data into a data collection form. We would have resolved all disagreements by consensus. We planned to contact authors of included studies to provide essential information missing from study reports. We would have extracted the following data:

Study methods

Design (e.g. randomized or quasi‐randomized)

Randomization method (including list generation)

Method of allocation concealment

Blinding method

Stratification factors

Participants

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Number (total/per group)

Age distribution

Severity of scoliosis

Level of scoliosis

Baseline respiratory function

Associated morbidities, e.g. cardiomyopathy

Previous treatments, including corticosteroids

Pretreatment quality of life and functional status, as measured by validated scales

Intervention and control

Type of spinal surgery

Type of control

Details of control treatment including duration of non‐operative treatment

Details of co‐interventions

Follow‐up data

Duration of follow‐up

Loss to follow‐up

Outcome data as described above

Analysis data

Methods of analysis (intention‐to‐treat/per‐protocol analysis)

Comparability of groups at baseline (yes/no)

Statistical techniques

Other

Funding

Conflicts of interest among main investigators

The data were entered into Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan) (RevMan 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We planned to have two review authors (DC and VW) independently assess the risk of bias of each included study. We would resolve any disagreements by consensus. We planned to evaluate the risk of bias of included trials using the following criteria in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011):

Selection bias

Was allocation of participants to treatment and control groups randomized?

Was allocation concealed?

Performance bias

Were participants in the comparison groups treated differently apart from the study treatments?

Was there blinding of participants and personnel?

Attrition bias

Were there systematic differences between the comparison groups in the loss of participants from the study?

Were analyses by intention‐to‐treat?

Detection bias

Were those assessing outcomes of the intervention blinded to the assigned intervention?

Reporting bias

Were there systematic differences between reported and unreported findings (incomplete outcome data)?

Other bias

Were there other issues that raise the possibility of bias, e.g. design‐specific risks?

We planned to summarize the quality of a trial into one of three categories:

Low risk of bias: all the validity criteria met.

Moderate risk of bias: one or more validity criteria partly met, but none are not met.

High risk of bias: one or more criteria not met.

Measures of treatment effect

We planned to use risk ratio estimations with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for binary outcomes. We planned to use mean difference estimations with 95% CIs for continuous outcomes. We planned to use hazard ratio estimations with 95% CIs for time‐to‐event (survival) outcomes. All analyses would have included all participants in the treatment groups to which they were allocated.

Dealing with missing data

We planned to contact authors of included studies to supply missing data. We would have assessed missing data and dropouts (attrition) for each included study, and assessed and discussed the extent to which the results and conclusions of the review could be altered by the missing data. If, at the end of the trial, data for a particular outcome were available for less than 70% of participants allocated to the treatments, we would not have used those data, as we would have considered them to be too prone to bias.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to assess clinical heterogeneity by comparing the distribution of important participant factors between trials (age, respiratory function, severity and level of scoliosis, associated diseases) and trial factors (allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, losses to follow‐up, treatment type, co‐interventions). We would have assessed statistical heterogeneity by examining I2, a quantity that describes approximately the proportion of variation in point estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2002). In addition, we would have used a Chi2 test for homogeneity to determine the strength of evidence that heterogeneity was genuine.

Assessment of reporting biases

We would have drawn funnel plots (estimated differences in treatment effects against their standard error) if we had found sufficient studies. Asymmetry can be due to publication bias, but can also be due to a relationship between trial size and effect size. In the event of a relationship being found, we would have examined clinical diversity of the studies (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

Where the interventions were the same or similar enough, we planned to synthesize results in a meta‐analysis if there was no important clinical heterogeneity. If no significant statistical heterogeneity was present, we planned to synthesize the data using a fixed‐effect model. Otherwise, we would have used a random‐effects model for the meta‐analysis.

Adverse events

Since numbers are small and follow‐up is too short in randomized studies for comprehensive adverse events reporting, we planned to discuss adverse events taking into account the non‐randomized literature.

Cost‐benefit analyses

Where relevant data were available, we planned to consider the cost‐effectiveness of interventions.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If data permitted, we planned to conduct subgroup analyses for:

different age groups (younger than 12 years, 12 to 18 years, older than 18 years);

different degrees of pre‐existing respiratory impairment (mild, severe);

different severity of scoliosis (moderate, severe);

previous corticosteroid treatments (yes, no).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to undertake sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of study quality. We would have undertaken these including:

all studies;

only those with low risk of selection bias;

only those with low risk of performance bias;

only those with low risk of attrition bias;

only those with low risk of detection bias.

We would also have performed sensitivity analysis including and excluding participants who might have Becker muscular dystrophy or an intermediate phenotype to see whether this would alter any of the results.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Alexander 2013 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Alman 1999 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Arun 2010 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Bellen 1993 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Bentley 2001 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Bridwell 1999 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Brook 1996 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Cambridge 1987 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Cervellati 2004 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Chataigner 1998 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Dubousset 1983 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Eagle 2007 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Gaine 2004 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Galasko 1992 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Galasko 1995 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Gayet 1999 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Granata 1996 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Hahn 2008 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Harper 2004 | Prospective case series, not clinical trial. |

| Heller 2001 | Prospective case series, not clinical trial. |

| Hopf 1994 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Kennedy 1995 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Kinali 2006 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| LaPrade 1992 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Marchesi 1997 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Marsh 2003 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Matsumura 1997 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Mehdian 1989 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Miller 1988 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Miller 1991 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Miller 1992 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Modi 2008a | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Modi 2008b | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Modi 2009 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Modi 2010 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Mubarak 1993 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Nakazawa 2010 | Prospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Rice 1998 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Rideau 1984 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Sakai 1977 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Sengupta 2002 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Shapiro 1992 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Stricker 1996 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Suk 2014 | Prospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Sussman 1984 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Takaso 2010 | Prospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Thacker 2002 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Velasco 2007 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

| Weimann 1983 | Retrospective case series, not clinical trial |

Differences between protocol and review

Risk of bias methodology updated in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Change in authorship: Tracy N'Diaye and Varaidzo Mayowe ceased authorship at an earlier update.

In the January 2015 update the electronic searches included the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform.

Contributions of authors

Daniel KL Cheuk: protocol development, searching for trials, quality assessment of trials, data extraction, data input, data analyses, development of final review, corresponding author.

Virginia Wong: protocol development, searching for trials, quality assessment of trials, data extraction, data analyses, development of final review.

Elizabeth Wraige: protocol development, searching for trials, quality assessment of trials, data extraction, data analyses, development of final review.

Peter Baxter: protocol development, searching for trials, quality assessment of trials, data extraction, data analyses, development of final review.

Ashley Cole: protocol development, searching for trials, quality assessment of trials, data extraction, data analyses, development of final review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

None, Other.

External sources

None, Other.

Declarations of interest

Daniel KL Cheuk: none known.

Virginia Wong: none known.

Elizabeth Wraige: none known.

Peter Baxter: no competing interests.

Ashley Cole:none known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies excluded from this review

Alexander 2013 {published data only}

- Alexander WM, Smith M, Freeman BJ, Sutherland LM, Kennedy JD, Cundy PJ. The effect of posterior spinal fusion on respiratory function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. European Spine Journal 2013;22(2):411‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Alman 1999 {published data only}

- Alman BA, Kim HK. Pelvic obliquity after fusion of the spine in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume 1999;81(5):821‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arun 2010 {published data only}

- Arun R, Srinivas S, Mehdian SMH. Scoliosis in Duchennes muscular dystrophy: A changing trend in surgical management: A historical outcome study comparing sublaminar, hybrid and pedical screw instrumentation systems. European Spine Journal 2010;19(3):376‐83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bellen 1993 {published data only}

- Bellen P, Hody JL, Clairbois J, Denis N, Soudon P. The surgical treatment of spinal deformities in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery (Hong Kong) 1993;7:48‐57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bentley 2001 {published data only}

- Bentley G, Haddad F, Bull TM, Seingry D. The treatment of scoliosis in muscular dystrophy using modified Luque and Harrington‐Luque instrumentation. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery ‐ Series B 2001;83(1):22‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bridwell 1999 {published data only}

- Bridwell KH, Baldus C, Iffrig TM, Lenke LG, Blanke K. Process measures and patient/parent evaluation of surgical management of spinal deformities in patients with progressive flaccid neuromuscular scoliosis (Duchenne's muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy). Spine 1999;24(13):1300‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brook 1996 {published data only}

- Brook PD, Kennedy JD, Stern LM, Sutherland AD, Foster BK. Spinal fusion in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics 1996;16(3):324‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cambridge 1987 {published data only}

- Cambridge W, Drennan JC. Scoliosis associated with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics 1987;7(4):436‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cervellati 2004 {published data only}