Abstract

Background

Recently, a novel systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) based on peripheral lymphocytes, neutrophils, and platelets has been reported to be correlated with patient prognosis in several malignancies, including gastric cancer. However, the prognostic value of the SII for gastric cancer patients with a signet-ring cell (SRC) component has not yet been reported. In this study, we aimed to assess the prognostic value of the SII in gastric cancer patients with an SRC component after curative resection.

Methods

This study was a retrospective analysis of 512 GC patients with an SRC component who underwent curative resection. The prognostic value of the SII was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method and Cox proportional hazards regression model.

Results

In our study cohort, an optimal cut-off value for the SII of 527 was used to stratify patients with gastric cancer (GC) into low (<527) and high SII (≥527) groups. Our study indicated that a high SII (≥527) was significantly correlated with a large tumor size (p < 0.001), infiltration of serosa (p < 0.001), lymph node metastasis (p < 0.001), and advanced TNM stage (p < 0.001). Univariate and multivariate analyses further demonstrated that a low SII was correlated with better clinical outcome and was an independent prognostic predictor in GC patients with an SRC component. Furthermore, the SII retained prognostic value in the subgroup analysis, including subgroup of different TNM stages and pure or mixed signet-ring cell carcinomas (SRCCs).

Conclusion

The SII is a simple, promising, and practical prognostic biomarker for patients with surgically resected mixed SRCC and pure SRCC. The SII could complement current prognostic tools for better treatment planning and stratification of patients.

1. Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the third leading cause of death from malignancy and the fifth most common carcinoma worldwide [1]. In the past two decades, obvious progress has been made in diagnosing and treating this lethal carcinoma via biological targeted therapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. The 5-year survival rate for patients with GC remains approximately 30% [2, 3]. Curative resection (R0 resection) remains the best option for patients with GC [4].

In recent years, although the incidence of GC has been reported to be decreasing, the proportion of diffuse-type GC in gastric cancer has been increasing [5, 6]. Correspondingly, the subtypes of the diffuse type of GC have also seen increasing incidence, including pure signet-ring cell cancer (pSRCC) and mixed signet-ring cell cancer (mSRCC) [2, 7].

Signet-ring cell (SRC) gastric cancer is a special type of histopathology in gastric cancer that features intracytoplasmic mucin within tumor cells that pushes the nucleus to the periphery [8]. The classifications developed by Sugano, Ming, and Lauren designate SRCC as “undifferentiated type,” “infiltrative type,” and “diffuse type,” respectively [9–11]. Some studies have demonstrated that SRCC has unique biological behavior and poor prognosis compared to other subtypes [12]. Therefore, research on gastric cancer with an SRC component (pSRCC and mSRCC) has an important value.

Until now, the TNM stage has been a major determinant for treatment planning and prognosis evaluation [13]. However, an accurate TNM stage can be obtained after surgery, and the role of the TNM stage in predicting prognosis is not perfect. Although gene analyses and molecular profiling have shown tremendous potential in instructing patient curative strategies, these technologies are expensive and complex at present [14, 15]. Therefore, the convenient and simple biomarkers in clinical practice that have aided in guiding patient stratification, determining curative strategies, and predicting prognosis have an important value.

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have indicated that inflammation is related to cancer [16]. Noticeably, an increasing number of scholars are paying more attention to inflammatory indexes that can reflect the whole-body state, such as the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), lymphocyte to neutrophil ratio (NLR), and prognostic nutritional index (PNI) [17, 18]. Recent studies have shown that the SII based on platelets, lymphocytes, and neutrophils as a combination biomarker can be utilized to predict prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma [19–21]. This novel comprehensive prognostic parameter combining peripheral platelets, lymphocytes, and neutrophils is superior to individual cell type-based factors in prognostic prediction, perhaps due to its more comprehensive reflection of the balance of immune status and host inflammation. However, the prognostic value of the SII in gastric cancer with an SRC component remains unexplored thus far.

In our study, the primary purpose was to evaluate the prognostic value of the SII in gastric cancer patients with an SRC component who received curative resection (R0 resection).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

Between May 2001 and December 2013, a total of 512 patients who were diagnosed with pSRCC or mSRCC and underwent gastrectomy at Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital, Harbin, China, were retrospectively analyzed. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients were diagnosed with pSRCC or mSRCC through pathological examination after radical surgery for gastric cancer (R0 resection); (2) patients received radical surgery for gastric cancer (R0 resection); (3) patients did not receive preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy; (4) patients were not allowed to receive nutrition replacement therapy or any drugs that may affect serum makers before collection of blood samples; and (5) patients had complete clinicopathological and follow-up data. In our study, patients who had immune or hematological disease, died of non-tumor-related causes, or died within one month after the operation were excluded. All blood biochemistry samples were collected within one week before surgery and examined by the laboratory department of Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital. The results of biochemistry tests and routine blood tests included tests of leukocytes (109/L), neutrophils (109/L), platelets (109/L), lymphocytes (109/L), serum fibrinogen (g/L), serum hemoglobin (g/L), serum prealbumin (g/L), serum albumin (g/L), and serum globulin (g/L). Other clinicopathological factors included sex, age, receipt of total gastrectomy, depth of tumor infiltration, lymph node metastasis, TNM stage [22], pathologic differentiation type [8], tumor size, and tumor location.

In the present study, the SII and NLR were calculated as follows: SII = N × P/L and NLR = N/L, where L, N, and P represent lymphocytes, neutrophils, and platelets, respectively; prognostic nutritional index (PNI) = serum albumin (g/L) + lymphocyte count × 5 (109/L).

2.2. pSRCC and mSRCC

In our study, signet-ring cell gastric carcinomas were classified based on the WHO diagnostic criteria. Cases with a relatively large amount of intracytoplasmic mucin (>50% of the tumor volume) within tumors were defined as pSRCCs; cases with a relatively small amount of intracytoplasmic mucin (10%-50% of the tumor volume) within tumors were defined as mSRCCs [7].

2.3. Follow-Up

The follow-up of patients was completed with the Gastric Tumor Information Management System V1.0 and the hospital follow-up group (follow-up was every 3 months in the first two years and every 6 months thereafter). The overall survival (OS) time was from the date of operation to the date of death or the date of last follow-up. Follow-up occurred from August 2001 to December 2018.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

SPSS 21.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for all statistical analyses. The optimal cut-off levels for prognostic factors were determined by ROC curve analysis. The correlation between the SII and characteristics was tested by a chi-square test. Survival differences were compared by the Kaplan-Meier method and a log-rank test. Multivariate prognosis analysis was performed using a Cox regression model with time-dependent covariates. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Result

3.1. Patient Characteristics

There were 512 patients in our study, with a median age of 55 years. The study included 332 males and 180 females and 68 cases of pSRCC and 444 cases of mSRCC. A total of 133 patients underwent total gastrectomy, and 399 patients underwent partial gastrectomy. A total of 292 patients were diagnosed with stage III disease, and 220 patients were diagnosed with stage I or II disease. There were 340 patients in the low SII (<527) group and 172 patients in the high SII (≥527) group (Table 1). A total of 244 (47.7%) patients received fluorouracil-based postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. Five years after surgery, 242 patients died.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 512 patients with gastric cancer with an SRC component.

| Variables | Value (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Men | 332 (64.8) |

| Women | 180 (35.2) |

| Age (years) | |

| <55 | 246 (48.0) |

| ≥55 | 266 (52.0) |

| SRCC | |

| pSRCC | 68 (13.3) |

| mSRCC | 444 (86.7) |

| Chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 244 (47.7) |

| No | 268 (52.3) |

| Tumor size(cm) | |

| <4.75 | 228 (44.5) |

| ≥4.75 | 284 (55.5) |

| pT | |

| T1 | 84 (16.4) |

| T2 | 64 (12.5) |

| T3 | 62 (12.1) |

| T4 | 302 (59.0) |

| pN | |

| N0 | 166 (32.4) |

| N1 | 86 (16.8) |

| N2 | 100 (19.5) |

| N3a | 102 (19.9) |

| N3b | 58 (11.4) |

| pTNM | |

| I+II | 220 (43.0) |

| III | 292 (57.0) |

| Tumor location | |

| Lower stomach | 328 (64.1) |

| Middle stomach | 75 (14.6) |

| Upper stomach | 35 (6.8) |

| LM stomach | 53 (10.3) |

| MU stomach | 7 (1.4) |

| LMU stomach | 14 (2.8) |

| Leukocyte | |

| <6.17 | 292 (57.0) |

| ≥6.17 | 220 (43.0) |

| Neutrophil | |

| <3.27 | 260 (50.8) |

| ≥3.27 | 252 (49.2) |

| Hemoglobin | |

| <121.2 | 140 (27.3) |

| ≥121.2 | 372 (72.7) |

| Fibrinogen | |

| <3.06 | 268 (52.3) |

| ≥3.06 | 244 (47.7) |

| Prealbumin | |

| <234.5 | 247 (48.2) |

| ≥234.5 | 265 (51.8) |

| Albumin | |

| <42.5 | 292 (57.0) |

| ≥42.5 | 220 (43.0) |

| Globulin | |

| <29.9 | 425 (83.0) |

| ≥29.9 | 87 (17.0) |

| SII | |

| <527 | 340 (66.4) |

| ≥527 | 172 (33.6) |

| PNI | |

| <48.73 | 176 (34.4) |

| ≥48.73 | 336 (65.6) |

| Total gastrectomy | |

| Yes | 113 (22.1) |

| No | 399 (77.9) |

| NLR | |

| <2.2 | 340 (66.4) |

| ≥2.2 | 172 (33.6) |

SRC: signet-ring cell; SRCC: signet-ring cell carcinoma; pSRCC: pure signet-ring cell cancer; mSRCC: mixed signet-ring cell cancer; LM: lower and middle; MU: middle and upper; LMU: lower, middle, and upper; SII: systemic immune-inflammation index; PNI: prognostic nutritional index; NLR: lymphocyte to neutrophil ratio.

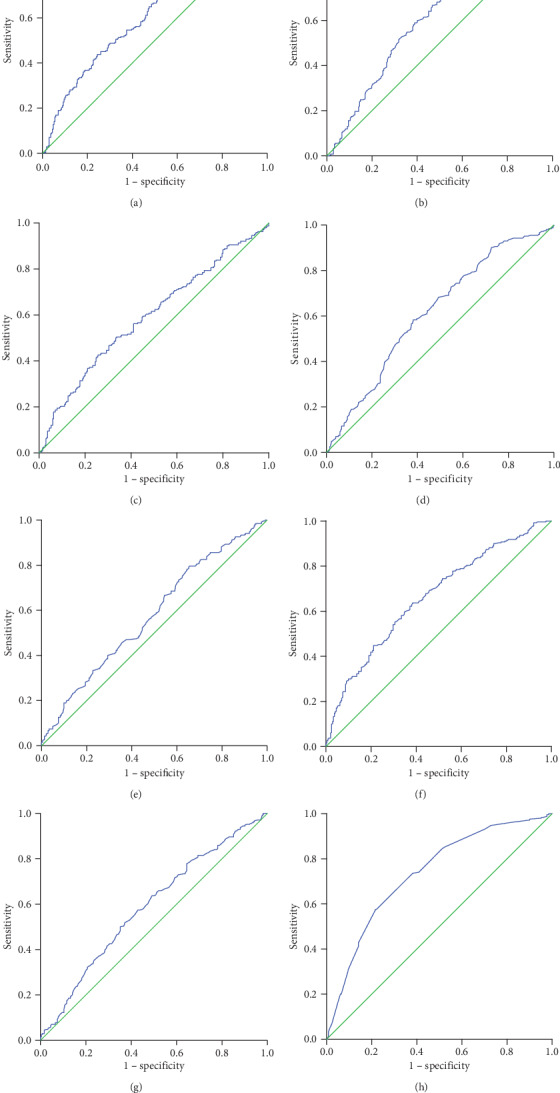

3.2. The Optimal Cut-off Values for Prognostic Factors

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, using 5-year OS rates as the end-point, for the SII, the PNI, the NLR, leukocyte count, neutrophil count, fibrinogen level, hemoglobin level, prealbumin level, albumin level, globulin level, and tumor size were generated. The area under curve (AUC) values for the SII, the PNI, the NLR, leukocyte count, neutrophil count, fibrinogen level, hemoglobin level, prealbumin level, albumin level, globulin level, and tumor size were 0.615 (p < 0.001), 0.615 (p < 0.001), 0.593 (p < 0.001), 0.502 (p = 0.941), 0.539 (p = 0.130), 0.617 (p = <0.001), 0.578 (p = 0.002), 0.662 (p < 0.001), 0.587 (p = 0.001), 0.505 (p = 0.855), and 0.735 (p < 0.001), respectively (Figure 1). The optimal cut-off level based on 5-year OS was determined to be 527 for the SII, 48.73 for the PNI, 2.2 for the NLR, 6.17 for leukocyte count, 3.27 for neutrophil count, 3.06 for fibrinogen level, 121.2 for hemoglobin level, 234.5 for prealbumin level, 42.5 for albumin level, 29.9 for globulin level, and 4.75 for tumor size (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of the (a) SII, (b) PNI, (c) NLR, (d) fibrinogen level, (e) hemoglobin level, (f) prealbumin level, (g) albumin level, and (h) tumor size.

Table 2.

The optimal cut-offs for prognostic factors according to ROC curves.

| Variables | Threshold | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC area (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size | 4.75 | 0.744 | 0.385 | 0.735 (0.692-0.778) | <0.001 |

| Leukocyte | 6.17 | 0.459 | 0.404 | 0.502 (0.452-0.552) | 0.941 |

| Neutrophil | 3.27 | 0.537 | 0.452 | 0.539 (0.489-0.589) | 0.130 |

| Hemoglobin | 121.2 | 0.793 | 0.653 | 0.578 (0.528-0.627) | 0.002 |

| Fibrinogen | 3.06 | 0.583 | 0.381 | 0.617 (0.569-0.665) | <0.001 |

| Prealbumin | 234.5 | 0.637 | 0.384 | 0.662 (0.616-0.709) | <0.001 |

| Albumin | 42.5 | 0.500 | 0.351 | 0.587 (0.538-0.637) | 0.001 |

| Globulin | 29.9 | 0.194 | 0.148 | 0.505 (0.454-0.555) | 0.855 |

| SII | 527 | 0.438 | 0.244 | 0.615 (0.566-0.664) | <0.001 |

| NLR | 2.2 | 0.426 | 0.256 | 0.593 (0.544-0.643) | <0.001 |

| PNI | 48.73 | 0.752 | 0.550 | 0.615 (0.566-0.663) | <0.001 |

ROC: receiver operating characteristic; AUC: area under curve; CI: confidence interval; SII: systemic immune-inflammation index; PNI: prognostic nutritional index; NLR: lymphocyte to neutrophil ratio.

3.3. Correlation between the SII and Patient Characteristics

There were 340 patients in the low SII (<527) group and 172 patients in the high SII (≥527) group. There was a significant difference between the low SII (<527) group and the high SII (≥527) group in terms of tumor size (p < 0.001), infiltration of serosa (p < 0.001), lymph node metastasis (p < 0.001), TNM stage (p < 0.001), leukocyte count (p < 0.001), neutrophil count (p < 0.001), serum hemoglobin level (p < 0.001), plasm fibrinogen level (p < 0.001), serum prealbumin level (p = 0.005), the PNI (p < 0.001), and the NLR (p < 0.001). We found that the patients in the high SII group seemed to have a larger tumor size, higher TNM stage, higher leukocyte count, higher neutrophil count, higher plasma fibrinogen level, and higher NLR than those in the low SII group. The high SII group seemed to have patients with higher serum hemoglobin levels, higher serum prealbumin levels, and higher PNI values than the low SII group (Table 3).

Table 3.

The correlation between the SII and other clinicopathological parameters.

| Variables | SII < 527 (cases) | SII ≥ 527 (cases) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||

| Sex | 0.062 | ||

| Men | 230 | 102 | |

| Women | 110 | 70 | |

| Age (years) | 0.414 | ||

| <55 | 159 | 87 | |

| ≥55 | 181 | 85 | |

| SRCC | 0.384 | ||

| mSRCC | 298 | 146 | |

| pSRCC | 42 | 26 | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.352 | ||

| Yes | 167 | 77 | |

| No | 173 | 95 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | <0.001 | ||

| <4.75 | 175 | 53 | |

| ≥4.75 | 165 | 119 | |

| pT | <0.001 | ||

| T1 | 74 | 10 | |

| T2 | 45 | 19 | |

| T3 | 39 | 23 | |

| T4 | 182 | 120 | |

| pN | <0.001 | ||

| N0 | 127 | 39 | |

| N1 | 60 | 26 | |

| N2 | 67 | 33 | |

| N3a | 60 | 42 | |

| N3b | 26 | 32 | |

| pTNM | <0.001 | ||

| I+II | 173 | 47 | |

| III | 167 | 125 | |

| Tumor location | 0.079 | ||

| Lower stomach | 227 | 101 | |

| Middle stomach | 49 | 26 | |

| Upper stomach | 25 | 10 | |

| LM stomach | 29 | 24 | |

| MU stomach | 2 | 5 | |

| LMU stomach | 8 | 6 | |

| Leukocyte | <0.001 | ||

| <6.17 | 230 | 62 | |

| ≥6.17 | 110 | 110 | |

| Neutrophil | <0.001 | ||

| <3.27 | 231 | 29 | |

| ≥3.27 | 109 | 143 | |

| Hemoglobin | <0.001 | ||

| <121.2 | 60 | 80 | |

| ≥121.2 | 280 | 92 | |

| Fibrinogen | <0.001 | ||

| <3.06 | 204 | 64 | |

| ≥3.06 | 136 | 108 | |

| Prealbumin | 0.005 | ||

| <234.5 | 149 | 98 | |

| ≥234.5 | 191 | 74 | |

| Albumin | 0.117 | ||

| <42.5 | 187 | 82 | |

| ≥42.5 | 153 | 90 | |

| Globulin | 0.292 | ||

| <29.9 | 278 | 147 | |

| ≥29.9 | 62 | 25 | |

| PNI | <0.001 | ||

| <48.73 | 92 | 84 | |

| ≥48.73 | 248 | 88 | |

| Total gastrectomy | 0.112 | ||

| Yes | 68 | 45 | |

| No | 272 | 127 | |

| NLR | <0.001 | ||

| <2.2 | 303 | 37 | |

| ≥2.2 | 37 | 135 |

SII: systemic immune-inflammation index; SRCC: signet-ring cell carcinoma; pSRCC: pure signet-ring cell cancer; mSRCC: mixed signet-ring cell cancer; LM: lower and middle; MU: middle and upper; LMU: lower, middle, and upper; PNI: prognostic nutritional index; NLR: lymphocyte to neutrophil ratio.

3.4. Univariate and Multivariate Survival Analyses

In the univariate analysis, we concluded that patients with younger age (p = 0.007), smaller tumor diameter (p < 0.001), shallower depth of tumor invasion (p < 0.001), no lymph node metastasis (p < 0.001), less advanced TNM stage (p < 0.001), a primary site within the lower third of the stomach (p < 0.001), low neutrophil level (p = 0.046), high hemoglobin level (p < 0.001), low plasma fibrinogen level (p < 0.001), high prealbumin level, high serum albumin level (p < 0.001), low NLR (p = 0.006), high PNI (p < 0.001), low SII (p < 0.001), and no receipt of total gastrectomy (p < 0.001) had better prognosis (Table 4). In subsequent multivariate analysis, the results demonstrated that SII (HR (95% CI): 1.634 (1.121-2.382), p = 0.011), depth of tumor invasion (HR (95% CI): 1.995 (1.562-2.548), p < 0.001), lymph node metastasis (HR (95% CI): 1.481 (1.282-1.711), p < 0.001), and receipt of total gastrectomy (HR (95% CI): 0.447 (0.324-0.618), p < 0.001) were independent risk factors for gastric cancer patients with an SRC component (Table 5).

Table 4.

Analysis of prognostic factors in 512 patients with gastric cancer with an SRC component.

| Variables | Survival analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| 5-YSR (%) | p value | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 53.3 | 0.639 |

| Female | 51.7 | |

| Age (years) | ||

| <55 | 58.5 | 0.007 |

| ≥55 | 47.4 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||

| <4.75 | 72.8 | <0.001 |

| ≥4.75 | 36.6 | |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 56.6 | 0.059 |

| No | 49.3 | |

| SRCC | ||

| mSRCC | 53.6 | 0.432 |

| pSRCC | 47.1 | |

| T-stage | ||

| T1 | 97.6 | <0.001 |

| T2 | 82.8 | |

| T3 | 50.0 | |

| T4 | 34.4 | |

| N-stage | ||

| N0 | 83.1 | <0.001 |

| N1 | 55.8 | |

| N2 | 47.0 | |

| N3a | 30.4 | |

| N3b | 10.3 | |

| TNM | ||

| I+II | 80.9 | <0.001 |

| III | 31.5 | |

| Tumor location | ||

| L | 59.5 | <0.001 |

| M | 49.3 | |

| U | 37.1 | |

| LM | 37.7 | |

| MU | 28.6 | |

| LMU | 21.4 | |

| Leukocyte | ||

| <6.17 | 55.1 | 0.229 |

| ≥6.17 | 49.5 | |

| Neutrophil | ||

| <3.27 | 56.9 | 0.046 |

| ≥3.27 | 48.4 | |

| Hemoglobin | ||

| <121.2 | 40.0 | <0.001 |

| ≥121.2 | 57.5 | |

| Fibrinogen | ||

| <3.06 | 62.3 | <0.001 |

| ≥3.06 | 42.2 | |

| Prealbumin | ||

| <234.5 | 39.7 | <0.001 |

| ≥234.5 | 64.9 | |

| Albumin | ||

| <42.5 | 46.2 | <0.001 |

| ≥42.5 | 61.4 | |

| Globulin | ||

| <29.9 | 54.1 | 0.170 |

| ≥29.9 | 46.0 | |

| NLR | ||

| <2.2 | 59.1 | 0.006 |

| ≥2.2 | 40.1 | |

| PNI | ||

| <48.73 | 38.1 | <0.001 |

| ≥48.73 | 60.4 | |

| SII | ||

| <527 | 60.0 | <0.001 |

| ≥527 | 38.4 | |

| Total gastrectomy | ||

| Yes | 22.1 | <0.001 |

| No | 61.4 | |

SII: systemic immune-inflammation index; SRCC: signet-ring cell carcinoma; pSRCC: pure signet-ring cell cancer; mSRCC: mixed signet-ring cell cancer; LM: lower and middle; MU: middle and upper; LMU: lower, middle, and upper; PNI: prognostic nutritional index; NLR: lymphocyte to neutrophil ratio.

Table 5.

Analysis of prognostic factors in 512 patients with gastric cancer with an SRC component by multivariate analysis.

| B | SE | Sig | Exp(B) | 95% CI for Exp(B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| T_COV_ | -0.003 | 0.006 | 0.652 | 0.997 | 0.986 | 1.009 |

| T_COV_1 | -0.008 | 0.006 | 0.167 | 0.992 | 0.981 | 1.003 |

| T-stage | 0.688 | 0.126 | <0.001 | 1.989 | 1.554 | 2.546 |

| N-stage | 0.413 | 0.075 | <0.001 | 1.512 | 1.305 | 1.751 |

| TNM stage | -0.241 | 0.269 | 0.370 | 0.786 | 0.464 | 1.331 |

| Tumor size | 0.134 | 0.163 | 0.410 | 1.143 | 0.831 | 1.573 |

| Age | 0.200 | 0.139 | 0.151 | 1.221 | 0.930 | 1.603 |

| Neutrophil | -0.221 | 0.176 | 0.209 | 0.802 | 0.568 | 1.132 |

| NLR | 0.000 | 0.186 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.695 | 1.438 |

| Hemoglobin | -0.001 | 0.151 | 0.996 | 0.999 | 0.744 | 1.342 |

| SII | 0.523 | 0.197 | 0.008 | 1.686 | 1.146 | 2.481 |

| PNI | 0.020 | 0.192 | 0.916 | 1.020 | 0.701 | 1.486 |

| Albumin | -0.128 | 0.188 | 0.498 | 0.880 | 0.609 | 1.273 |

| Total gastrectomy | -0.809 | 0.180 | <0.001 | 0.446 | 0.313 | 0.633 |

| Tumor location LMU | 0.436 | |||||

| Tumor location L | 0.431 | 0.352 | 0.222 | 1.538 | 0.771 | 3.068 |

| Tumor location M | 0.276 | 0.360 | 0.444 | 1.317 | 0.651 | 2.665 |

| Tumor location U | 0.650 | 0.384 | 0.091 | 1.915 | 0.901 | 4.068 |

| Tumor location LM | 0.136 | 0.361 | 0.707 | 1.145 | 0.565 | 2.323 |

| Tumor location MU | 0.384 | 0.561 | 0.494 | 1.468 | 0.489 | 4.405 |

SII: systemic immune-inflammation index; LM: lower and middle; MU: middle and upper; LMU: lower, middle, and upper; PNI: prognostic nutritional index; NLR: lymphocyte to neutrophil ratio; T_COV_: fibrinogen time-dependent variable; T_COV_1: prealbumin time-dependent variable.

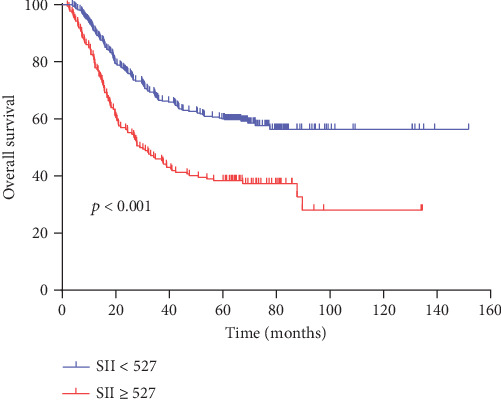

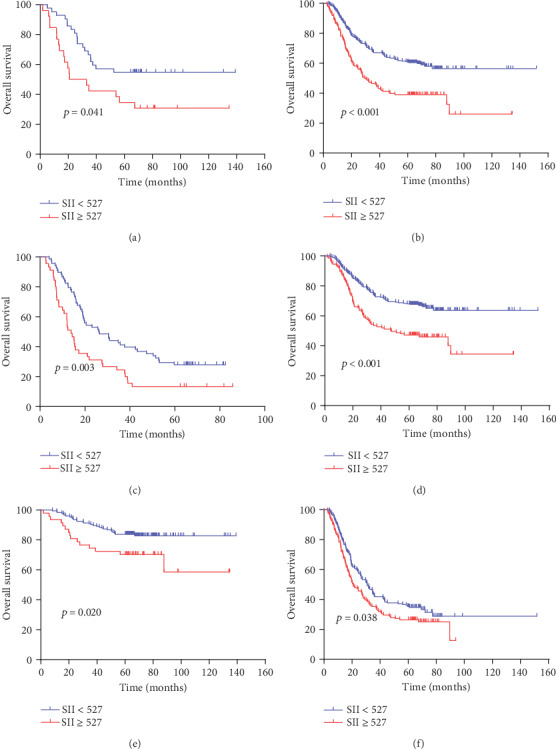

3.5. The SII and OS in Subgroup Analysis

The 5-year OS rates between the low SII group and the high SII group were significantly different (60.0% vs. 38.4%, respectively, p < 0.001, Figure 2). We further investigated the prognostic value of the SII in pure and mixed SRCC, patients with and without receipt of total gastrectomy, and patients with different TNM stages. A strong relationship between the SII and OS was found in both pure and mixed SRCC (p = 0.041 for pSRCC, p < 0.001 for mSRCC, Figures 3(a) and 3(b)), in both patients who did and patients who did not receive total gastrectomy (p = 0.003 for receipt of total gastrectomy, p < 0.001 for no receipt of total gastrectomy, Figures 3(c) and 3(d)), and patients with different TNM stages (p = 0.020 for stage I+II, p = 0.038 for stage III, Figures 3(e) and 3(f)).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (OS) for the SII in all patients with gastric cancer.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of OS for the SII in patients with gastric cancer. (a) Kaplan-Meier analysis of OS for the SII in patients with gastric cancer in the pSRCC group; (b) Kaplan-Meier analysis of OS for the SII in patients with gastric cancer in the mSRCC group; (c) Kaplan-Meier analysis of OS for the SII in patients with gastric cancer in the total gastrectomy resection group; (d) Kaplan-Meier analysis of OS for the SII in patients with gastric cancer in the nontotal gastrectomy resection group; (e) Kaplan-Meier analysis of OS for the SII in patients with gastric cancer in stages I+II; (f) Kaplan-Meier analysis of OS for the SII in patients with gastric cancer in stage III.

4. Discussion

In our study, we determined the prognostic value of the SII in patients with an SRC component who received radical surgery. The results showed that the SII was a prognostic indicator in gastric cancer patients with an SRC component.

Currently, evaluating prognosis in gastric cancer patients is mainly based on TNM staging, which considers characteristics such as histological type, nodal involvement, depth of invasion, distant metastasis, and tumor size, among others [23]. Nevertheless, gastric cancer patients with equivalent clinical and pathological staging may experience different outcomes. The results suggested that other pathological characteristics are related to cancer progression.

In recent years, a few biomarkers were found to be related to poor outcomes in patients with cancer, and they are therefore used to monitor recurrence and to predict prognosis. Increasing studies have shown that the tumor-associated inflammatory response plays a principal role in the progression and development of diverse organ cancers. Therefore, an increasing number of scholars are paying more attention to systemic inflammatory indicators [24, 25]. The SII, which is based on lymphocytes, platelets, and neutrophils, appears to be a powerful prognostic index in a variety of malignancies, including gastric cancer [26–28].

In recent years, a meta-analysis including 7,657 patients from 22 articles showed that a high SII was related to poor survival in patients with a variety of cancers regardless of cut-off value, ethnicity, and sample size [29]. Currently, a meta-analysis of 24 studies (involving a total of 9626 patients) found that a high SII was greatly associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with gastrointestinal cancers [30]. A study from China showed that preoperative SII was not only an independent prognostic factor for survival in patients with gastric cancer but also significantly associated with OS in different stages [31]. These results strongly support the prognostic value of the SII in gastric cancer.

The mechanism by which the SII affects the occurrence and progression of gastric cancer may include the following aspects. First, neutrophils can promote distant metastasis by triggering both parenchymal and endothelial cells to intensify circulating tumor cell adhesion [32]. In addition, neutrophils can secrete both molecules that lead to DNA damage and substances that promote angiogenesis, such as vascular endothelial growth factor [33]. Second, platelets can promote distant metastasis by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition; on the other hand, platelets can serve as a protective “cloak” to defend circulating tumor cells from immune destruction [34]. In cancer cells, the NF-κB and TGFβ/Smad pathways are activated by direct platelet-tumor cell interactions and platelet-derived TGFβ effectors, which induce mesenchymal-like transition and cooperate to promote metastasis. Therefore, platelets play a main role in cancer cell metastasis and survival [35]. Third, lymphocytes can induce cytotoxic cell death and cytokine secretion, as well as suppress tumor cell migration and proliferation, to control tumor growth [36]. In addition, a low lymphocyte level was associated with poor survival in cancer, possibly because the host's anticancer immunity is weakened as lymphocyte levels decrease [37].

We found that a higher SII may represent higher neutrophil levels, higher platelet levels, and lower lymphocyte levels. According to the above existing mechanisms, the results suggested that a higher SII fundamentally means weaker immune defense and a stronger inflammatory response in patients with cancer, which leads to poor survival.

In our study, we found that a high SII was related to advanced tumor invasion, lymph node metastasis, advanced TNM stage, and large tumor size in gastric cancer patients with an SRC component. In one study of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, Feng et al. showed that a high SII is related to advanced TNM stage and large tumor size [38]. Similarly, the study results of Huang et al. were also consistent with the results of our study [39]. These results strongly support the close relationship between inflammation and cancer and demonstrate that the inflammatory response parallels tumor progression to a certain degree. By analyzing patients with an SRC component, we found that the 5-year survival rate in the low SII group was significantly higher than that in the high SII group (60.0% vs. 38.4%, p < 0.001), and more significantly, the SII was still statistically significant in the multivariate analysis of SRCC patient overall survival. Therefore, the SII is an independent risk factor affecting the prognosis of GC patients with an SRC component. Nie et al. suggested that the SII is an independent prognostic factor for epithelial ovarian cancer [40]. Tao et al. found that compared with a low SII, a high SII was significantly correlated with a lower overall survival rate 5 years after surgery [41]. These results strongly support the conclusions of our study.

Clinical and pathological staging obtained by surgical and postoperative histological examination is still the main index to evaluate the prognosis and survival of patients. However, compared to such staging, the SII is simpler and more convenient to calculate. In addition, the SII is repeatable and generalizable. Therefore, the SII is very applicable in clinical practice.

Significantly, we found in the subgroup analysis that the SII was significantly associated with OS regardless of the type of SRCC (pSRCC or mSRCC), receipt of total gastrectomy (total gastrectomy or no total gastrectomy), and TNM stage (I+II stage or III stage). These results reinforce the value of the SII in the prognostic assessment of GC patients with an SRC component and suggest that it is a complementary method to clinical and pathological TNM staging.

The SII is a comprehensive indicator composed of three elements (neutrophils, platelets, and lymphocytes), which can comprehensively reflect the changes in human physiology, so it has an important clinical value for early detection, determination of treatment, and evaluation of prognosis in GC patients with an SRC component. Although there have been previous studies on the SII and GC, they included patients with all types of gastric cancer, while our study included only GC patients with an SRC component, which enabled a more detailed and accurate identification of more representative prognostic factors for patients with this specific subset of GC. Therefore, our study on whether the SII can be used as a clinical feature to evaluate the prognosis of GC patients with an SRC component is of great significance and value.

Currently, most studies have looked at the SII in patients from different countries and regions. In addition, the SII has been evaluated by different methods, such as analyses of ROC curves, medians, and averages, in previous studies. Therefore, we cannot determine the ideal SII cut-off value. In addition, the mechanisms by which neutrophils, lymphocytes, and platelets affect cancer are also controversial. Whether a preoperative increase in SII suggests promotion or inhibition of peripheral blood neutrophils, lymphocytes, and platelets in the human body is not known. This is also a limitation of this study. Although we searched for the mechanism behind a preoperative SII increase through cell experiments, immunohistochemistry, and animal experiments, we were unable to find it, and prospective, multicenter, and large-sample studies are needed to define and clarify the optimal cut-off value for the SII.

In summary, we believe that gastric cancer patients should be more carefully stratified and that SRCC should be regarded as a disease with its own unique clinical and pathological characteristics. In addition, the SII should be regarded as an important reference and evaluation tool for both early cancer screening in unaffected populations and prognostication of patients with cancer.

In conclusion, we found that a high SII was associated with poor OS in gastric cancer patients with an SRC component. This biomarker may help clinicians to predict patient prognosis.

Contributor Information

Chunfeng Li, Email: lichunfeng007@163.com.

Yingwei Xue, Email: xueyingwei@hrbmu.edu.cn.

Data Availability

No data were used to support this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Ziyu Zhu and Xiliang Cong contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.de Aguiar V. G., Segatelli V., Macedo A. L. V., et al. Signet ring cell component, not the Lauren subtype, predicts poor survival: an analysis of 198 cases of gastric cancer. Future Oncology. 2019;15(4):401–408. doi: 10.2217/fon-2018-0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu M., Yang Z., Feng Q., et al. The characteristics and prognostic value of signet ring cell histology in gastric cancer: a retrospective cohort study of 2199 consecutive patients. Medicine. 2016;95(27, article e4052) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun X., Liu X., Liu J., et al. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio plus platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in predicting survival for patients with stage I–II gastric cancer. Chinese Journal of Cancer. 2016;35(1):p. 57. doi: 10.1186/s40880-016-0122-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li P., Huang C. M., Zheng C. H., et al. Comparison of gastric cancer survival after R0 resection in the US and China. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2018;118(6):975–982. doi: 10.1002/jso.25220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;69(1):7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henson D. E., Dittus C., Younes M. D., et al. Differential trends in the intestinal diffuse types of gastric carcinoma in the United States, 1973-2000: increase in the signet ring cell type. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 2005;129(3):p. 290. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-765-DTITIA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu Q., Dekusaah R., Cao S., et al. Risk factors of lymph node metastasis in patients with early pure and mixed signet ring cell gastric carcinomas. Journal of Cancer. 2019;10(5):1124–1131. doi: 10.7150/jca.29245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fléjou J. F. Classification OMS 2010 des tumeurs digestives : la quatrième édition. Ann Pathol. 2011;31(5):S27–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.annpat.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugano H., Nakamura K., Kato Y. Pathological studies of human gastric cancer. Acta Pathologica Japonica. 1982;32(Supplement 2):329–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ming S. C. Gastric carcinoma. A pathobiological classification. Cancer. 1977;39(6):2475–2485. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197706)39:6<2475::AID-CNCR2820390626>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type CARCINOMA. Acta Pathologica et Microbiologica Scandinavica. 1965;64(1):31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon K. J., Shim K. N., Song E. M., et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17(1):43–53. doi: 10.1007/s10120-013-0234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bando E., Makuuchi R., Irino T., Tanizawa Y., Kawamura T., Terashima M. Validation of the prognostic impact of the new tumor-node-metastasis clinical staging in patients with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22(1):123–129. doi: 10.1007/s10120-018-0799-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H. S., Cho S. B., Lee H. E., et al. Protein expression profiling and molecular classification of gastric cancer by the tissue array method. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13(14):4154–4163. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higaki E., Kuwata T., Nagatsuma A. K., et al. Gene copy number gain of EGFR, is a poor prognostic biomarker in gastric cancer: evaluation of 855 patients with bright-field dual in situ hybridization (DISH) method. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19(1):63–73. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shigdar S., Li Y., Bhattacharya S., et al. Inflammation and cancer stem cells. Cancer Letters. 2014;345(2):271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong S., Zhou T., Fang W., et al. The prognostic nutritional index (PNI) predicts overall survival of small-cell lung cancer patients. Tumor Biology. 2015;36(5):3389–3397. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2973-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo W., Cai S. H., Zhang F., et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) is useful to predict survival outcomes in patients with surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer. Thoracic Cancer. 2019;10(4):761–768. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang P., Yue W. S., Li W. Y., et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index and ultrasonographic classification of breast imaging-reporting and data system predict outcomes of triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Management and Research. 2019;11:813–819. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S185890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu B., Yang X. R., Xu Y., et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2014;20(23):6212–6222. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aziz M. H., Sideras K., Aziz N. A., et al. The systemic-immune-inflammation index independently predicts survival and recurrence in resectable pancreatic cancer and its prognostic value depends on bilirubin levels: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Annals of Surgery. 2019;270(1):139–146. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiu M. Z., Wang Z. X., Zhou Y. X., Yang D. J., Wang F. H., Xu R. H. Proposal for a new TNM stage based on the 7thand 8thAmerican Joint Committee on Cancer pTNM staging classification for gastric cancer. Journal of Cancer. 2018;9(19):3570–3576. doi: 10.7150/jca.26351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao B. C., Zhang J. T., Zhang J. L., et al. Assessment of the 8th edition of TNM staging system for gastric cancer: the results from the SEER and a single-institution database. Future Oncology. 2018;14(29):3023–3035. doi: 10.2217/fon-2018-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beal E. W., Wei L., Ethun C. G., et al. Elevated NLR in gallbladder cancer and cholangiocarcinoma – making bad cancers even worse: results from the US Extrahepatic Biliary Malignancy Consortium. HPB. 2016;18(11):950–957. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinato D. J., North B. V., Sharma R. A novel, externally validated inflammation-based prognostic algorithm in hepatocellular carcinoma: the prognostic nutritional index (PNI) British Journal of Cancer. 2012;106(8):1439–1445. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li C., Tian W., Zhao F., et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index, SII, for prognosis of elderly patients with newly diagnosed tumors. Oncotarget. 2018;9(82):35293–35299. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chovanec M., Cierna Z., Miskovska V., et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index in germ-cell tumours. British Journal of Cancer. 2018;118(6):831–838. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi H. T., Jiang Y. Q., Cao H. G., Zhu H., Chen B., Ji W. Nomogram based on systemic immune-inflammation index to predict overall survival in gastric cancer patients. Disease Markers. 2018;2018:11. doi: 10.1155/2018/1787424.1787424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang R. N., Chang Q., Meng X. C., Gao N., Wang W. Prognostic value of systemic immune-inflammation index in cancer: a meta-analysis. Journal of Cancer. 2018;9(18):3295–3302. doi: 10.7150/jca.25691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y., Lin S. B., Yang X. J., Wang R., Luo L. Prognostic value of pretreatment systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with gastrointestinal cancers. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2019;234(5):5555–5563. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang K., Diao F., Ye Z., et al. Prognostic value of systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with gastric cancer. Chinese Journal of Cancer. 2017;36(1):p. 75. doi: 10.1186/s40880-017-0243-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Larco J. E., Wuertz B. R., Furcht L. T. The potential role of neutrophils in promoting the metastatic phenotype of tumors releasing interleukin-8. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(15):4895–4900. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang W., Ferrara N. The complex role of neutrophils in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Cancer Immunology Research. 2016;4(2):83–91. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stanger B. Z., Kahn M. L. Platelets and tumor cells: a new form of border control. Cancer Cell. 2013;24(1):9–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Labelle M., Begum S., Hynes R. O. Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial- mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(5):576–590. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferrone C., Dranoff G. Dual roles for immunity in gastrointestinal cancers. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(26):4045–4051. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.27.9992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mlecnik B., Tosolini M., Kirilovsky A., et al. Histopathologic-based prognostic factors of colorectal cancers are associated with the state of the local immune reaction. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(6):610–618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng J. F., Chen S., Yang X. Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) is a useful prognostic indicator for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Medicine. 2017;96(4, article e5886) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang H. P., Liu Q., Zhu L. X., et al. Prognostic value of preoperative systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with cervical cancer. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1, article 3284) doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39150-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nie D., Gong H., Mao X. G., Li Z. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer: a retrospective study. Gynecologic Oncology. 2019;152(2):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tao M. Y., Wang Z. H., Zhang M. H., et al. Prognostic value of the systematic immune-inflammation index among patients with operable colon cancer: a retrospective study. Medicine. 2018;97(45, article e13156) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data were used to support this study.