Abstract

A vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) has been actively sought for over 60 years due to the health impacts of RSV disease in infants, but currently the only available preventive measure in Canada and elsewhere is limited to passive immunization for high-risk infants and children with a monoclonal antibody.

RSV vaccine development has faced many challenges, including vaccine-induced enhancement of RSV disease in infants. Several key developments in the last decade in the fields of cellular immunology and protein structure have led to new products entering late-stage clinical development. As of July 2019, RSV vaccine development is being pursued by 16 organizations in 121 clinical trials. Five technologies dominate the field of RSV vaccine development, four active immunizing agents (live-attenuated, particle-based, subunit-based and vector-based vaccines) and one new passive immunizing agent (monoclonal antibody). Phase 3 clinical trials of vaccine candidates for pregnant women, infants, children and older adults are under way. The next decade will see a dramatic transformation of the RSV prevention landscape.

Keywords: vaccine, National Advisory Committee on Immunization, NACI, immunization, RSV, respiratory syncytial virus

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection represents a large burden of disease in Canada and worldwide. The age distribution of RSV disease burden is bimodal, with the greatest impact felt in the first two years of life and in older adults. Annually, RSV disease is estimated to cause 3.4 million hospitalizations and 100,000 deaths globally (1). In Canada, the burden of RSV disease and hospitalizations are captured by various surveillance systems. Although preventive and supportive medical interventions exist to prevent or treat RSV, vaccination holds hope as a method to reduce the health and economic burden of RSV.

RSV is an orthopneumovirus in the Pneumoviridae family. It is a negative-sense, single-stranded RNA virus that has 11 proteins (2). The F protein on the surface of the viral membrane mediates fusion between the virus and the host cell. Two conformations of F have been defined, prefusion and postfusion. Some neutralizing epitopes are present on both conformations, notably site II targeted by palivizumab. Other neutralizing epitopes are present only on prefusion F, including the sites V (targeted by suptavumab) and ø (targeted by nirsevimab). Without specific stabilization or modification, the F protein will exist in a spectrum of conformations, which will have different antigenic and neutralization profiles. Without stabilization, this immunogen will settle into a postfusion conformation over time.

Two subtypes of RSV have been defined, RSV/A and RSV/B. Subtype A is more prevalent than subtype B (3). RSV infects cells in the human airway, including polarized, differentiated, ciliated epithelial cells, and causes infection of the upper and lower airways. Severe disease clinically manifests as influenza-like illnesses and lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI), with bronchiolitis the most common severe presentation in young children. Primary RSV infections can result in symptomatic LRTI, a minority of which require hospitalization. Canadian surveillance to capture the RSV burden in different populations is under way.

The only countermeasure currently available for RSV is palivizumab, a monoclonal antibody administered prophylactically to infants and children under two years of age at higher risk for severe infection.

A vaccine against RSV has been sought after for over 60 years for its potential impacts on the health outcomes for various age groups. A shadow was cast over vaccine development in the 1960s when a formalin-inactivated RSV (FI-RSV) vaccine was tested in seronegative children, that is, they were naive to RSV antigens. Instead of inducing protection, immunization resulted in enhanced respiratory disease (ERD) upon subsequent RSV infection, leading to two deaths (4–7).

Recently, RSV vaccine development has leveraged advances in understanding of T-cell biology and protein structure as well as a better delineation of different populations at risk for RSV. As of July 2019, 16 organizations were undertaking RSV vaccine development in 121 clinical trials. Vaccine candidates are in development for children, older adults and pregnant women. Phase 3 clinical trials that target pediatric, older adult and maternal populations are under way.

Five technologies dominate the field of RSV vaccine development: four active immunizing agents (live-attenuated, particle-based, subunit-based and vector-based vaccines) and one new passive immunizing agent (i.e. monoclonal antibody). Other trials are in late preclinical and early clinical stages.

The objective of this overview is to summarize the vaccine candidates in the five different vaccine technologies for three target populations and to identify current challenges to developing a vaccine for RSV.

Key Findings

Immunization technologies and strategies

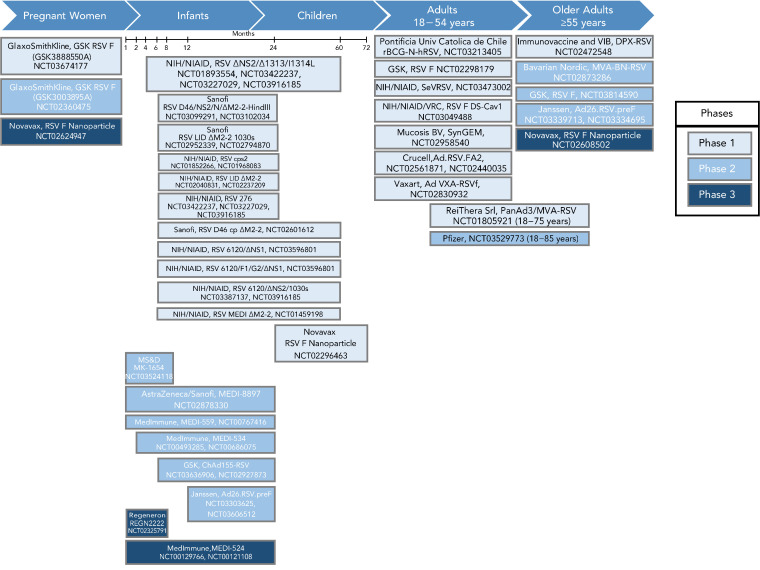

Clinical trials are under way for maternal, pediatric and older adult populations. Based on data collected through July 1, 2019, Figure 1 represents the RSV vaccine products in development for each target population at risk for RSV. Phase 3 clinical trials that target maternal, senior adult and pediatric populations are under way. Below we summarize the developments for each vaccine candidate type, with an emphasis on products in later stages of clinical development (Stage 2 or 3 clinical trials).

Figure 1.

Summary of RSV vaccine target populations

Abbreviations: BN, Bavarian Nordic; DPX, DepoVax; MVA, modified Vaccinia Ankara virus; NCT, National Clinical Trial; NIAD, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NIH, National Institutes of Health; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SeVRSV, Sendai virus vectored respiratory syncytial virus; VRC, Vaccine Research Center

Note: Each box (listing the developing organization and the NCT number) represents a vaccine candidate in a phase of clinical development. As the phase of development increases the colour of the box becomes darker. These boxes are organized by the target population that closely aligns with the populations at risk for severe disease. As with other vaccines in development, early Phase 1 clinical trials that assess safety are done in healthy adults and later stages of clinical trials (Phases 2 and 3) are done in the target population of interest to assess efficacy and effectiveness

Adapted from: Graham (2019) (8)

Live-attenuated vaccines

Live-attenuated vaccines are versions of RSV that are able to replicate but have been modified to discourage severe disease. They can be created by traditional techniques (i.e. temperature or chemical sensitivity) or by reverse genetics to create an attenuated-replication competent vaccine. The challenge of this technique is to decrease the pathogenicity of the virus but to maintain the replicative function to stimulate immune responses. One of the key downsides, however, is the possibility of partial reversion to wild-type virus (9).

This technique represents several advantages: possible needle-free delivery by intranasal administration; lack of enhanced disease (10); in the case of intranasal vaccines, replication in the presence of maternal antibodies (11); and stimulation of cellular and humoral immunity systemically and locally (12). No vaccine candidates of this type have progressed beyond Phase 2 clinical trials. The replicative nature of this vaccine and the reduced danger of ERD, makes it an attractive strategy for seronegative infants.

Vector-based vaccines

Vector-based vaccines are created from components of the RSV virus inserted into a carrier vector, to create a chimeric vector. This chimeric vector replicates according to the carrier vector properties and induces immune responses to both the insert and carrier sequences. The intent is for the carrier vector to enhance responses to the RSV components. This platform is attractive for both pediatric and older adult populations due to the reduced risk of ERD. Unlike live-attenuated vaccines, the chimeric nature of these vectors means there is no risk of reversion to wild-type RSV. In addition, replicating vectors are able to boost the immune responses to the inserted sequences. Several companies are using variations of this platform as RSV vaccine candidates. (See infographic for an overview of the products from each manufacturer).

Bavarian Nordic (BN) is developing a vector from modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) virus, based on the orthopox virus used as a vaccine against smallpox. This vector is used to express several RSV antigens, including wild-type F, G, N, M2-1, and potentially other proteins. This candidate is in the Phase 2 clinical trials of MVA-BN-RSV in older adults [National Clinical Trial (NCT)02873286] for either a one or two-dose strategy via intramuscular route of administration. This trial has demonstrated that this vaccine induces both B and T-cell responses and neutralizing antibodies.

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) is developing a nonreplicating vector from Chimpanzee Adenovirus 155 (ChAd155), a simian adenovirus engineered by GSK to produce F, N and M2-1. The version of RSV F protein inserted into this vector lacked the transmembrane domain and the conformation of F is unknown. In adults, this intramuscular vaccine was safe and well-tolerated and induced cellular and humoral immune responses. This vaccine is currently in Phase 2 clinical trials in seropositive infants aged six months and older (NCT03636906). Phase 2 clinical trials in seronegative infants (aged 6–11 months) are in progress.

Janssen is developing a vector from Adenovirus 26 (Ad26), a human adenovirus, as a carrier vector for prefusion F protein antigens. This vector is being assessed in older adults and infants in Phase 2 clinical trials (NCT03606512; NCT03982199). In seniors, this vector is being assessed alone and in conjunction with a subunit protein (NCT03502707).

Subunit-based vaccines

Subunit-based vaccines are composed of purified viral proteins. They are administered alone or with adjuvant, often as an aqueous solution or emulsion, depending on the route of administration or the adjuvant to boost immune responses. This type of vaccine is expected to predominately induce humoral responses and CD4+ T-cell activation (13). The lack of CD8+ T-cell responses and the history of ERD necessitates caution in the use of this type of vaccine in seronegative infants. In seropositive populations, including older adults and pregnant women, these types of vaccines represent the opportunity to boost protective antibody responses. Fusion protein or prefusion protein-based vaccines may or may not be synonymous based on their antigenicity profiles and/or features of their high-resolution structures.

GSK is developing a stabilized prefusion protein vaccine candidate. It is in development for maternal populations and in Phase 2 for older adults (NCT03814590). In Phase 1 testing, the alum adjuvant had no effect on neutralizing antibody responses (NCT02298179). The unadjuvanted product was intended for Phase 2 clinical trial in pregnant women, but it was withdrawn due to issues with protein stability during manufacturing (NCT03191383).

Janssen is developing a subunit vaccine candidate that is being assessed with and without an adenovirus vaccine. This protein is reported to be in the prefusion conformation. A new candidate of the fusion protein stabilized in its prefusion conformation is now in Phase 2 trials for both the older adult and maternal populations. This program is currently in Phase 1/2 clinical trials (NCT03502707).

Particle-based vaccines

Particle-based vaccines are composed of synthesized nanoscopic particles that present multiple copies of a selected antigen to the immune system. The intent is to boost immunological responses to immunogens by the high copy number and the immune-boosting properties of the particle matrix.

Novavax developed a recombinant fusion protein particle vaccine with polysorbate 80, ResVax. The conformation of this immunogen was a singly cleaved prefusogenic form (14). In Phase 1 clinical trials in older populations and pregnant women, ResVax was safe and produced palivizumab-competing antibodies (15). However, in Phase 3 clinical trials in older populations, this candidate did not meet the primary outcome (preventing RSV-associated moderate–severe lower respiratory tract disease) or the secondary outcome (reduce all symptomatic respiratory disease due to RSV) (NCT02608502). Currently, a Phase 2 trial is planned to evaluate a reformulation. In Phase 3 clinical trials in pregnant women, this vaccine did not meet its primary objective (prevention of medically significant RSV-related LRTI in young infants) but still demonstrated 39% efficacy in reducing RSV-induced LRTI within the first 90 days of life and in reducing hospitalization by 44%, with the most protection seen if the vaccine was delivered before 33 weeks gestation (NCT02624947).

Monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies against RSV have been used as passive immunizing agents. Even once vaccine programs exist, monoclonal antibodies may continue to provide prophylaxis in populations where active immunization will not be effective, such as immunocompromised individuals, or to severely premature infants who receive little or no maternal antibodies. The downside to this technology is that passive antibodies are only protective for as long as they remain in circulation. The passive protection of the passive monoclonal antibody currently available, palivizumab, lasts about a month. New monoclonal antibodies are being developed that could have a higher potency and longer duration of activity.

AstraZeneca/Sanofi Pasteur is developing nirsevimab (MEDI8897), a recombinant human anti-RSV monoclonal antibody that has been engineered with a triple amino acid substitution in the constant domain to increase its serum half-life. This antibody targets neutralization-sensitive site ø at the apex of the prefusion F protein. One dose of this product could be effective for up to 5–6 months and provide protection for a whole RSV season due to increased potency and increased half-life (16). The increased period of effectiveness for this product could particularly serve to benefit rural and remote communities with reduced access to health care resources and where monthly travel is currently required to obtain palivizumab.

Regeneron was developing REGN2222 (suptavumab), a monoclonal antibody. This product was fast-tracked from Phase 1 to Phase 3 clinical trials by the Food and Drug Administration in October 2015, but did not meet its primary endpoint of preventing medically attended RSV infection within the first 150 days of life (NCT02325791).

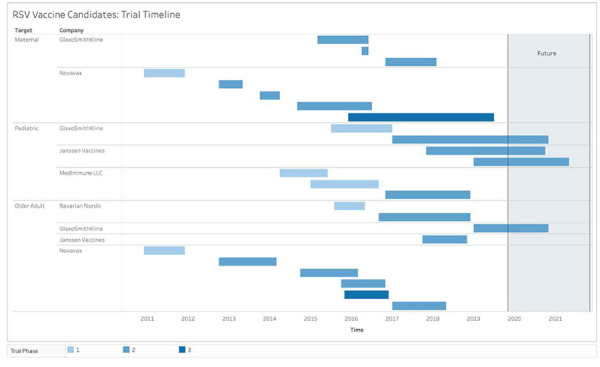

In summary, five different strategies are being pursued to address the challenges of vaccine development for RSV infection. Over 100 trials have been conducted on 38 candidates, and eight new trials were initiated last year alone. Based on data collected through July 1, 2019, Figure 2 describes the timeline of the clinical testing of products in late-stage clinical development. This RSV product development pipeline is becoming increasingly crowded, and it is possible that new vaccines for RSV may be introduced into the Canadian market in the next 2–5 years.

Figure 2.

Summary of RSV vaccine products timelinea

Abbreviation: RSV, respiratory syncytial virus

a Based on data collected through July 1, 2019, this figure describes the timeline of the clinical testing of products in late-stage clinical development. Each box represents a product in a phase of clinical development. As the phase of development increases the colour of the box becomes darker

Challenges to RSV vaccine development

Antigen diversity

A successful vaccine candidate will account for the diversity of antigens presented by RSV in the form of the structural variability of the proteins on the surface of the virus. The protective, neutralizing antibody response to RSV is dominated by antibodies targeting the prefusion F protein on the surface of RSV (17,18). Although the genetic sequence of F does not vary substantially between strains of RSV [89% of its sequence is identical in both A and B strains (19)], amino acids do vary in prefusion specific epitopes. As new products are authorized and make it into broad usage, it will be critical to understand the sero-epidemiological responses at a population level to understand whether prefusion or postfusion antibodies are dominant responses, and whether these demonstrate equivalent protection against both RSV type A and B.

RSV infection dampens the immune response

The second major challenge of RSV vaccine development implicates the cellular and humoral immune responses: RSV infection dampens immune responses. RSV surface and internal proteins can trigger cellular immune responses and antibody-dependant cellular cytotoxicity alongside humoral immune responses. However, several viral mechanisms act to diminish virus-specific proliferative and effector responses (20). Even when cellular responses are not dampened by viral mechanisms, they may or may not offer protection. The CD8 T-cell mediated response to RSV is complex and has been associated with both viral clearance and disease pathology, depending on the type and location of the cells (21,22). The response mediated by CD4+ T-cells is also not straightforward as helper T-cell subset 2 biased CD4 responses have been associated with adverse vaccine reactions, yet are needed to induce antibody-mediated responses and other cellular responses, including T-follicular helper cells and effector cells (23,24). The key for vaccine development is to bolster immune responses, despite the dampening effect of RSV, to achieve the aims of the vaccine program: humoral responses may be targeted to prevent infection and cellular responses may be augmented to prevent severe disease (25). Clear definitions of correlates of protection for each of these immune responses are needed to ensure that seroconversion during trials translates to vaccine efficacy.

There are no clear correlates of protection

The third major challenge is the lack of clear correlates of protection for at-risk populations. Natural infection does not induce protection, as evidenced by the fact that 100% of children are infected by age two years but RSV disease recurs across age demographics. Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that children can be naturally reinfected with the same strain of virus, but that the second and subsequent infections are less severe (26,27), and there have been similar findings in adults (28). Why this is unclear; it may be a combination of low viral immunogenicity or hampered immunological boosting by recurrent infections (29). Current biological markers of protection are humoral, as measured by assays that determine antibody specificity (including the palivizumab-competition assay) and function (neutralization assays). However, this may not be sufficient, as illustrated by the late-stage failure of a monoclonal antibody from Regeneron (suptavumab).

Different correlates of protection may be needed for the two populations at risk for severe RSV disease: infants and older adults. Infants pose a challenge for vaccination as they have underdeveloped immune capabilities. This population may be susceptible to vaccine-induced ERD, as observed in the formalin-inactivated RSV trials. ERD has been attributed to low antibody efficacy (30) and Th2-biased CD4 immune responses (31–33). The aims of direct and indirect immunization programs for infants includes protection of infection, severe disease and hospitalization (34). Discussions are underway in some jurisdictions to define the thresholds of protection in multiple humoral and cellular correlates of protection needed before advancing clinical trials into seronegative populations (35).

Older adults face a different challenge in that the immune responses they have developed are waning due to immunosenescence. Immunization in older adults may have different aims and different correlates of protection depending on the health priorities of the jurisdiction (34). To prevent infection, humoral correlates of protection may be monitored. To prevent severe disease, cellular correlates of protection may be monitored. These two aims are not mutually exclusive, but a vaccine candidate may be better suited at achieving one of the aims over the other. To create a vaccine that is both efficacious and effective, vaccine manufacturers need to consider the public health goals of the vaccine programs and use correlates of protection in preclinical and clinical phases of development that align with these goals.

Discussion

The key to vaccine development will be eliciting an age-appropriate immune response in each target population. Current vaccine strategies are mindful of the history of ERD and the unique immunological characteristics and vulnerability of seronegative children. Live-attenuated and virus-vectored vaccines are two vaccination strategies that are appealing for infants and children, as replicating vaccines do not prime vaccine-enhanced RSV disease (10,36,37). Neonates can also acquire immunity against RSV from their mothers. Active transplacental antibody transfer begins at 28–30 weeks gestation, and maternal vaccination to boost anti-RSV response is intended to confer increased infant protection postpartum (38). Maternal and infant immunization strategies are being pursued to indirectly and directly target the infant population.

Older adults face different challenges in that they are already seropositive but face immunosenescence. To boost the immunological repertoire of this at-risk population, direct and indirect immunization strategies, such as vaccination of children (as with Rotavirus) (39), may be pursued.

The field of vaccine development for respiratory viruses is rapidly expanding. Technologies tested and proved effective in one field elicit development across the board. Structure-based immunogen design, spurred from publication of the pre-F structure in 2013 (40), has bolstered the development of new RSV vaccines across multiple vaccine platforms (see Figure 2). Technologies to identify and isolate B cells with receptors of interest is enabling the identification of monoclonal antibodies with useful characteristics. Regulatory and production timelines for these products may be faster than for traditional vaccines, putting pressure on expert groups to create guidance within shorter timeframes. mRNA-based vaccines may shorten production timelines further.

Conclusion

Substantial progress has been made in the RSV vaccine development field. Federal, provincial and territorial public health departments in Canada and abroad need to be aware of new products as they are closer to market—how they have addressed the key challenges in RSV vaccine development and how they work to achieve the public health goals for RSV in each jurisdiction.

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to acknowledge the significant contribution of N Winters to creation of the figures.

Conflict of interest: None.

Funding: This work is supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

References

- 1.Shi T, McAllister DA, O’Brien KL, Simoes EA, Madhi SA, Gessner BD, Polack FP, Balsells E, Acacio S, Aguayo C, Alassani I, Ali A, Antonio M, Awasthi S, Awori JO, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Baggett HC, Baillie VL, Balmaseda A, Barahona A, Basnet S, Bassat Q, Basualdo W, Bigogo G, Bont L, Breiman RF, Brooks WA, Broor S, Bruce N, Bruden D, Buchy P, Campbell S, Carosone-Link P, Chadha M, Chipeta J, Chou M, Clara W, Cohen C, de Cuellar E, Dang DA, Dash-Yandag B, Deloria-Knoll M, Dherani M, Eap T, Ebruke BE, Echavarria M, de Freitas Lázaro Emediato CC, Fasce RA, Feikin DR, Feng L, Gentile A, Gordon A, Goswami D, Goyet S, Groome M, Halasa N, Hirve S, Homaira N, Howie SR, Jara J, Jroundi I, Kartasasmita CB, Khuri-Bulos N, Kotloff KL, Krishnan A, Libster R, Lopez O, Lucero MG, Lucion F, Lupisan SP, Marcone DN, McCracken JP, Mejia M, Moisi JC, Montgomery JM, Moore DP, Moraleda C, Moyes J, Munywoki P, Mutyara K, Nicol MP, Nokes DJ, Nymadawa P, da Costa Oliveira MT, Oshitani H, Pandey N, Paranhos-Baccalà G, Phillips LN, Picot VS, Rahman M, Rakoto-Andrianarivelo M, Rasmussen ZA, Rath BA, Robinson A, Romero C, Russomando G, Salimi V, Sawatwong P, Scheltema N, Schweiger B, Scott JA, Seidenberg P, Shen K, Singleton R, Sotomayor V, Strand TA, Sutanto A, Sylla M, Tapia MD, Thamthitiwat S, Thomas ED, Tokarz R, Turner C, Venter M, Waicharoen S, Wang J, Watthanaworawit W, Yoshida LM, Yu H, Zar HJ, Campbell H, Nair H; RSV Global Epidemiology Network. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children in 2015: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet 2017. Sep;390(10098):946–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30938-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins PL, Fearns R, Graham BS. Respiratory syncytial virus: virology, reverse genetics, and pathogenesis of disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2013;372:3–38. 10.1007/978-3-642-38919-1_1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mufson MA, Orvell C, Rafnar B, Norrby E. Two distinct subtypes of human respiratory syncytial virus. J Gen Virol 1985;66 (Pt 10)(Pt 10):2111-24. 10.1099/0022-1317-66-10-2111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chin J, Magoffin RL, Shearer LA, Schieble JH, Lennette EH. Field evaluation of a respiratory syncytial virus vaccine and a trivalent parainfluenza virus vaccine in a pediatric population. Am J Epidemiol 1969. Apr;89(4):449–63. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fulginiti VA, Eller JJ, Sieber OF, Joyner JW, Minamitani M, Meiklejohn G. Respiratory virus immunization. I. A field trial of two inactivated respiratory virus vaccines; an aqueous trivalent parainfluenza virus vaccine and an alum-precipitated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine. Am J Epidemiol 1969. Apr;89(4):435–48. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kapikian AZ, Mitchell RH, Chanock RM, Shvedoff RA, Stewart CE. An epidemiologic study of altered clinical reactivity to respiratory syncytial (RS) virus infection in children previously vaccinated with an inactivated RS virus vaccine. Am J Epidemiol 1969. Apr;89(4):405–21. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HW, Canchola JG, Brandt CD, Pyles G, Chanock RM, Jensen K, Parrott RH. Respiratory syncytial virus disease in infants despite prior administration of antigenic inactivated vaccine. Am J Epidemiol 1969. Apr;89(4):422–34. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham BS. Immunological goals for respiratory syncytial virus vaccine development. Curr Opin Immunol 2019. Aug;59:57–64. 10.1016/j.coi.2019.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HW, Arrobio JO, Brandt CD, Wright P, Hodes D, Chanock RM, Parrott RH. Safety and antigenicity of temperature sensitive (TS) mutant respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in infants and children. Pediatrics 1973. Jul;52(1):56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright PF, Karron RA, Belshe RB, Shi JR, Randolph VB, Collins PL, O’Shea AF, Gruber WC, Murphy BR. The absence of enhanced disease with wild type respiratory syncytial virus infection occurring after receipt of live, attenuated, respiratory syncytial virus vaccines. Vaccine 2007. Oct;25(42):7372–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright PF, Karron RA, Belshe RB, Thompson J, Crowe JE Jr, Boyce TG, Halburnt LL, Reed GW, Whitehead SS, Anderson EL, Wittek AE, Casey R, Eichelberger M, Thumar B, Randolph VB, Udem SA, Chanock RM, Murphy BR. Evaluation of a live, cold-passaged, temperature-sensitive, respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate in infancy. J Infect Dis 2000. Nov;182(5):1331–42. 10.1086/315859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karron RA, Wright PF, Belshe RB, Thumar B, Casey R, Newman F, Polack FP, Randolph VB, Deatly A, Hackell J, Gruber W, Murphy BR, Collins PL. Identification of a recombinant live attenuated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate that is highly attenuated in infants. J Infect Dis 2005. Apr;191(7):1093–104. 10.1086/427813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossey I, Saelens X. Vaccines against human respiratory syncytial virus in clinical trials, where are we now? Expert Rev Vaccines 2019. Oct;18(10):1053–67. 10.1080/14760584.2019.1675520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith G, Raghunandan R, Wu Y, Liu Y, Massare M, Nathan M, Zhou B, Lu H, Boddapati S, Li J, Flyer D, Glenn G. Respiratory syncytial virus fusion glycoprotein expressed in insect cells form protein nanoparticles that induce protective immunity in cotton rats. PLoS One 2012;7(11):e50852. 10.1371/journal.pone.0050852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fries L, Shinde V, Stoddard JJ, Thomas DN, Kpamegan E, Lu H, Smith G, Hickman SP, Piedra P, Glenn GM. Immunogenicity and safety of a respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein (RSV F) nanoparticle vaccine in older adults. Immun Ageing 2017;14:8-017-0090-7. https://10.1186/s12979-017-0090-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu Q, McLellan JS, Kallewaard NL, Ulbrandt ND, Palaszynski S, Zhang J, Moldt B, Khan A, Svabek C, McAuliffe JM, Wrapp D, Patel NK, Cook KE, Richter BWM, Ryan PC, Yuan AQ, Suzich JA. A highly potent extended half-life antibody as a potential RSV vaccine surrogate for all infants. Sci Transl Med 2017;9(388): eaaj1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilman MS, Castellanos CA, Chen M, Ngwuta JO, Goodwin E, Moin SM, Mas V, Melero JA, Wright PF, Graham BS, McLellan JS, Walker LM. Rapid profiling of RSV antibody repertoires from the memory B cells of naturally infected adult donors. Sci Immunol 2016;1(6):eaaj1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ngwuta JO, Chen M, Modjarrad K, Joyce MG, Kanekiyo M, Kumar A, Yassine HM, Moin SM, Killikelly AM, Chuang GY, Druz A, Georgiev IS, Rundlet EJ, Sastry M, Stewart-Jones GB, Yang Y, Zhang B, Nason MC, Capella C, Peeples ME, Ledgerwood JE, McLellan JS, Kwong PD, Graham BS. Prefusion F-specific antibodies determine the magnitude of RSV neutralizing activity in human sera. Sci Transl Med 2015. Oct;7(309):309ra162. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullender WM. Respiratory syncytial virus genetic and antigenic diversity. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000. Jan;13(1):1–15. 10.1128/CMR.13.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyoglu-Barnum S, Chirkova T, Anderson LJ. Biology of infection and disease pathogenesis to guide RSV vaccine development. Front Immunol 2019. Jul;10(1675):1–28. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J, Haddad EK, Marceau J, Morabito KM, Rao SS, Filali-Mouhim A, Sekaly RP, Graham BS. A numerically subdominant CD8 T cell response to matrix protein of respiratory syncytial virus controls infection with limited immunopathology. PLoS Pathog 2016. Mar;12(3):e1005486. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt ME, Knudson CJ, Hartwig SM, Pewe LL, Meyerholz DK, Langlois RA, Harty JT, Varga SM. Memory CD8 T cells mediate severe immunopathology following respiratory syncytial virus infection. PLoS Pathog 2018. Jan;14(1):e1006810. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruckwardt TJ, Bonaparte KL, Nason MC, Graham BS. Regulatory T cells promote early influx of CD8+ T cells in the lungs of respiratory syncytial virus-infected mice and diminish immunodominance disparities. J Virol 2009. Apr;83(7):3019–28. 10.1128/JVI.00036-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu J, Cao S, Peppers G, Kim SH, Graham BS. Clonotype-specific avidity influences the dynamics and hierarchy of virus-specific regulatory and effector CD4(+) T-cell responses. Eur J Immunol 2014. Apr;44(4):1058–68. 10.1002/eji.201343766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Domachowske JB, Rosenberg HF. Respiratory syncytial virus infection: immune response, immunopathogenesis, and treatment. Clin Microbiol Rev 1999. Apr;12(2):298–309. 10.1128/CMR.12.2.298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agoti CN, Mwihuri AG, Sande CJ, Onyango CO, Medley GF, Cane PA, Nokes DJ. Genetic relatedness of infecting and reinfecting respiratory syncytial virus strains identified in a birth cohort from rural Kenya. J Infect Dis 2012. Nov;206(10):1532–41. 10.1093/infdis/jis570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohuma EO, Okiro EA, Ochola R, Sande CJ, Cane PA, Medley GF, Bottomley C, Nokes DJ. The natural history of respiratory syncytial virus in a birth cohort: the influence of age and previous infection on reinfection and disease. Am J Epidemiol 2012. Nov;176(9):794–802. 10.1093/aje/kws257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall CB, Walsh EE, Long CE, Schnabel KC. Immunity to and frequency of reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis 1991. Apr;163(4):693–8. 10.1093/infdis/163.4.693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munir S, Hillyer P, Le Nouën C, Buchholz UJ, Rabin RL, Collins PL, Bukreyev A. Respiratory syncytial virus interferon antagonist NS1 protein suppresses and skews the human T lymphocyte response. PLoS Pathog 2011. Apr;7(4):e1001336. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy BR, Walsh EE. Formalin-inactivated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine induces antibodies to the fusion glycoprotein that are deficient in fusion-inhibiting activity. J Clin Microbiol 1988. Aug;26(8):1595–7. 10.1128/JCM.26.8.1595-1597.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graham BS, Henderson GS, Tang YW, Lu X, Neuzil KM, Colley DG. Priming immunization determines T helper cytokine mRNA expression patterns in lungs of mice challenged with respiratory syncytial virus. J Immunol 1993. Aug;151(4):2032–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor G. Bovine model of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2013;372:327–45. 10.1007/978-3-642-38919-1_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polack FP, Teng MN, Collins PL, Prince GA, Exner M, Regele H, Lirman DD, Rabold R, Hoffman SJ, Karp CL, Kleeberger SR, Wills-Karp M, Karron RA. A role for immune complexes in enhanced respiratory syncytial virus disease. J Exp Med 2002. Sep;196(6):859–65. 10.1084/jem.20020781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Killikelly A, Shane A, Yeung MW, Tunis M, Bancej C, House A, Vaudry W, Moore D, Quach C. Gap analyses to assess Canadian readiness for respiratory syncytial virus vaccines: report from an expert retreat. Can Commun Dis Rep 2020;46(4):62–8. 10.14745/ccdr.v46i04a02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Browne SK, Beeler JA, Roberts JN. Summary of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee meeting held to consider evaluation of vaccine candidates for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus disease in RSV-naïve infants. Vaccine 2020. Jan;38(2):101–6. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karron RA, Buchholz UJ, Collins PL. Live-attenuated respiratory syncytial virus vaccines. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2013;372:259–84. 10.1007/978-3-642-38919-1_13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waris ME, Tsou C, Erdman DD, Day DB, Anderson LJ. Priming with live respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) prevents the enhanced pulmonary inflammatory response seen after RSV challenge in BALB/c mice immunized with formalin-inactivated RSV. J Virol 1997. Sep;71(9):6935–9. 10.1128/JVI.71.9.6935-6939.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogilvie MM, Vathenen AS, Radford M, Codd J, Key S. Maternal antibody and respiratory syncytial virus infection in infancy. J Med Virol 1981;7(4):263–71. 10.1002/jmv.1890070403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamin D, Jones FK, DeVincenzo JP, Gertler S, Kobiler O, Townsend JP, Galvani AP. Vaccination strategies against respiratory syncytial virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016. Nov;113(46):13239–44. 10.1073/pnas.1522597113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLellan JS, Chen M, Leung S, Graepel KW, Du X, Yang Y, Zhou T, Baxa U, Yasuda E, Beaumont T, Kumar A, Modjarrad K, Zheng Z, Zhao M, Xia N, Kwong PD, Graham BS. Structure of RSV fusion glycoprotein trimer bound to a prefusion-specific neutralizing antibody. Science 2013. May;340(6136):1113–7. 10.1126/science.1234914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]