Abstract

Background:

Little is known about the extent to which routine care management of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and intermittent claudication (IC) align with best practice recommendations on exercise therapy. We conducted a scoping review to examine the published literature on the availability and workings of exercise therapy in the routine management of patients with PAD and IC, and the attitude and practice of health professionals and patients.

Methods:

A systematic search was conducted in February 2018. The Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Ovid MEDLINE, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, ScienceDirect, Web of Science and the Directory of Open Access Repositories were searched. Hand searching of reference lists of identified studies was also performed. Inclusion criteria were based on study aim, and included studies that reported on the perceptions, practices, and workings of routine exercise programs for patients with IC, their availability, access, and perceived barriers.

Results:

Eight studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review. Studies conducted within Europe were included. Findings indicated that vascular surgeons in parts of Europe generally recognize supervised exercise therapy as a best practice treatment for IC, but do not often refer their patients for supervised exercise therapy due to the unavailability of, or lack of access to supervised exercise therapy programs. Available supervised exercise therapy programs do not implement best practice recommendations, and in the majority, patients only undergo one session per week. Some challenges were cited as the cause of the suboptimal program implementation. These included issues related to patients’ engagement and adherence as well as resource constraints.

Conclusion:

There is a dearth of published research on exercise therapy in the routine management of PAD and IC. Available data from a few countries within Europe indicated that supervised exercise is underutilized despite health professionals recognizing the benefits. Research is needed to understand how to improve the availability, access, uptake, and adherence to the best exercise recommendations in the routine management of people with PAD and IC.

Keywords: supervised exercise, intermittent claudication, peripheral arterial disease, scoping review

Introduction

The most common symptom of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is intermittent claudication (IC)1 defined as exertional pain in the lower limb(s), which is relieved by rest. IC limits individuals’ exercise capacity, decreases functional ability, and leads to a poorer quality of life.2–4 Individuals with PAD and IC have lower levels of physical activity compared with their age-matched healthy controls.5,6 Exercise therapy is the most effective conservative therapy for improving walking capacity in people with IC.7–11 Exercise therapy is an important area of research in PAD and IC care internationally, and is recommended by several professional guidelines.7,12–14 Although both supervised and unsupervised exercise programs improve pain-free and maximal walking distances in IC,15–17 best evidence recommendations support the use of supervised exercise programs (SEPs).18,19 A recent Cochrane review update provided high-quality evidence that SEPs are more beneficial compared with placebo or usual care in improving both pain-free and maximum walking distance in people with symptomatic IC.20

Despite the level of evidence for the use of exercise therapy for the management of PAD and IC, and the professional bodies’ guidelines and endorsements, there are concerns that this is yet to be given a priority in the management of IC.21,22 Access to, and uptake of healthcare is determined by factors within and outside the healthcare system.23,24 Some of the important stakeholders within this system are the patients, healthcare professionals, and the hospital management. To maximize patient outcomes related to exercise treatments for IC, the patients, healthcare professionals, and facilities involved in IC treatment should align their management with best evidence recommendations. However, little is known about the extent to which routine care treatments for IC align with best practice recommendations on exercise therapy.

There is a close association between individuals’ attitudes and beliefs and their practices.25 It has been suggested that healthcare professionals’ self-interest and wider health system factors, but not lack of evidence, are among the main challenges in adopting and implementing exercise recommendations for IC.21,26 This underscores the importance of understanding perceptions and practices related to routine provision of exercise for IC. No systematic review has examined the attitudes, beliefs, or practices of healthcare professionals, facilities, or patients regarding exercise provision in the routine care of IC.

Methods

Design and rationale

We performed a scoping review using the five stages of the Arksey and O’Malley scoping review methodology27 as revised by Levac et al.28 The completed review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews.29 A scoping review design was justified given that no prior systematic review evidence exists regarding the type and extent of available literature, and the need to summarize systematically primary research in an effective and timely manner. Findings will provide direction to reflect on ways of enhancing delivery of best practice exercise recommendations in the routine care of people with IC.

Step 1: identifying the research question

The aim of this scoping review was to scope the literature on perceptions, practices, and workings of routine exercise programs for patients with IC, their availability, access, and perceived barriers.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

Search strategy

The search strategy was deliberately narrow and intended to retrieve only peer-review published articles with a mention of exercise or exercise programs or walking or supervised exercise or home-based exercise or exercise therapy and PAD or IC (and their synonymous terms) in their title, keywords, or abstracts.

Identification of primary research studies

A search was implemented in five databases (CINAHL via EBSCO, MEDLINE via ProQuest, AMED via Ovid, ScienceDirect, Social citation index/Science citation index/Emerging sources citation index via Web of Science) and the Directory of Open Access Repositories website until February 2018 with no date parameters. The reference lists of included articles were checked for relevant studies. Search terms were identified by exploring the National Library of Medicine Subject Headings (MESH), in addition to exploring the keywords of relevant articles. The search strategy was developed by the primary author (UOA), with support of a co-author (ODA). The following keywords were used: provision OR availability OR attitude OR perceptions OR perspective OR access OR accessibility AND exercise OR physical activity OR exercise training OR supervised exercise OR supervised exercise programs OR walking exercise OR walking program OR walking OR home-based exercise OR unsupervised exercise AND peripheral arterial disease OR peripheral vascular disease OR intermittent claudication OR intermittent claudication treatment. Abstract searches were performed for those words using Boolean operators, searching related terms and limited only to English language literature. An example of a detailed search strategy is shown in Appendix 1.

Stage 3: study selection

Data management, screening and extraction

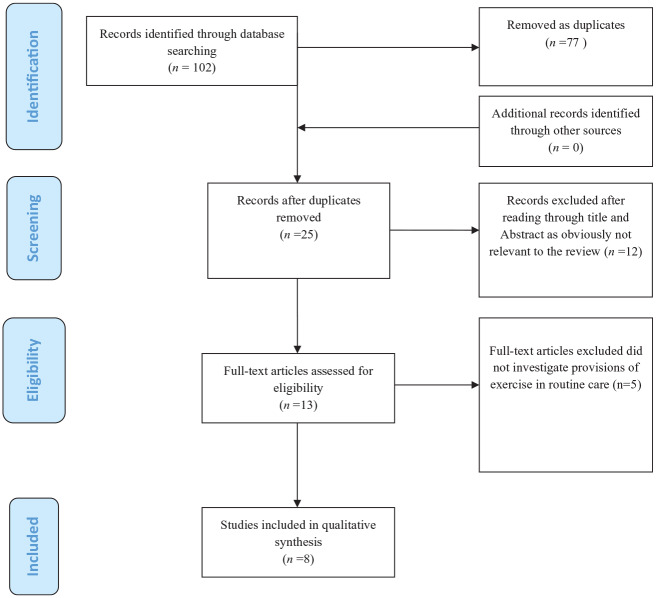

The identified studies were imported to Refworks™ and duplicates removed. Studies were then exported to Microsoft Excel 2010 where the screenings were undertaken. Specific eligibility criteria were developed through iteration and piloting, and included the removal of studies that did not investigate exercise in routine care. Initially, titles and abstracts of identified studies were independently screened by two authors (UOA, DD) and overtly irrelevant studies were excluded. Next, the full text of selected studies after abstract and title screening were read independently to determine studies’ inclusion in the review. Differences of opinion regarding inclusion or exclusion were resolved by discussion and reaching consensus between the two authors (UOA, DD), or in consultation with a third author (CAS) when consensus could not be reached. The process of identifying, screening, and inclusion of studies is summarized in Figure 1. All articles had sufficient information enabling a decision on eligibility and inclusion; no study author was contacted to request missing information.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram adapted for a scoping review of exercise programs for peripheral arterial disease and intermittent claudication in routine care.

Excluded papers – did not report on routine provision of exercise (Guidon and McGee)11.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles meeting the following criteria were included in the review: (a) studies that focused on the healthcare workforce directly or indirectly involved in exercise therapy for patients with IC (e.

g. GPs, surgeons, physiotherapists, nurses, exercise physiologists) or focused on the description of routine delivery of exercise for individuals with PAD and IC (description could be reported by either healthcare professionals or patients); (b) studies that reported on the provision, attitude, access, availability, or other factors regarding routine exercise for IC; (c) studies of any design published in English and reported primary data whether published as full length articles or only as abstracts. No restriction was placed regarding publication date.

Stage 4: charting the data

Critical appraisal

Given the review objective to scope the extent and type of literature, a quality appraisal was not implemented for this scoping review. This is consistent with current guidelines for conducting systematic scoping reviews.30

Data collection and synthesis

Study characteristics were recorded in a data extraction form specifically developed and piloted for this review (Table 1). Data elements included authors’ details (author, year, and country), study aim, participant characteristics, study design, findings, and authors’ main conclusions. Studies meeting inclusion criteria were summarized in a narrative synthesis, including the overall number of studies, geographical location, design, population, and summary of results (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies and data extraction table.

| Author details, country | Study aim(s) | Study design, data collection and

analysis methods Level of evidence |

Study participant demographics/settings/cultural context | Response rate | Outcomes | Results | Authors main conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harwood et al.31

UK |

To determine the current provision of supervised exercise for IC and the factors affecting provision | Cross-sectional online survey | Members of The Vascular Society of Great Britain and

Ireland UK NHS trusts |

(n = 89/361; 24.6%), representing (n = 59/97; 57%) of vascular units | Program type and detail of exercise

program Program uptake and compliance Plans of program introduction if not available |

Access to SEPs for NHS patient in a hub center:

surgeons (37/89; 41.6%), vascular units/trust

(22/57; 38.5%) Program types Hospital-based group SEP (n = 19), homebased SEP (n = 2), both (n = 1) program details in the trusts: hospital-based group SEP (n = 20) personnel: PT (n = 10) specialist nurse (n = 9) exercise professional (n = 1) duration: 12 weeks (n = 18), <12 weeks (n = 1), >12 weeks (n = 1) per session duration: 30–60 min session frequency: one/week (n = 16) two/week (n = 3) three/week (n = 1) components: aerobics only (n = 8), resistance training + aerobics (n = 12) Program uptake and compliance: mostly not formally documented. Best guess data: only 9/14 units had ⩾40% uptake rate; up to 13/16 units had ⩾50% completion rate. Home-based (n = 3) personnel: PT (n = 1) specialist nurse (n = 1) exercise professional (n = 1) duration: 12 weeks session frequency/per session duration/components: 1 h of resistance twice/week OR 1 h of aerobics once/week Program uptake and compliance: not formally documented. Best guess data: 2/3 units had ⩾40% uptake rate; all 3/3 units had ⩾50% of completion rate. Plan in place to introduce SEP: yes (13/57; 22.8%) no plan (18/57; 31.6%) |

SEPs are not available to the majority of patients with PAD in the UK. This is largely due to inadequate funding, and lack of patients’ motivation and adherence to SEPs which is still poorly understood. |

| Bartelink et al.32

The Netherlands |

To investigate the role of GPs and physiotherapists in noninvasive therapy for patients with IC | Cross-sectional postal survey | Random sample of GPs and physiotherapists in two Dutch provinces | 57% (226/400) and 100% (209), respectively | GPs provision of walking service/follow up/referral

to a physiotherapist Physiotherapists management of patients with IC/number treated in a year/availability of treadmill |

GPs: 194/226 (86%) gave any form of advice to

patients with IC to walk 147/226 (65%) gave one-off advice to walk without specific advice or follow up to patient 22/226 (10%) only gave flyers of patient organizations Only 23/226 (15%) referred patients to a physiotherapist for walking. Physiotherapists: only 16/209 (8%) occasionally treated patients with IC 13/16 treated only 1–4 patients/year Only 6/209 (2.9%) had access to a treadmill |

Walking exercise provision for persons with IC in Dutch primary care is low and requires improvement. |

| Bartelink et al.

33

The Netherlands |

To evaluate the number of patients with IC accessing advice about walking/ number who started to walk | Mixed method | Dutch patients with IC from Dutch primary care

Sample size n = 216 Mean age:

66.9 years (range 42–97 years) Gender:

69% Focus group n = 9 |

Response rate: 58% | Persons from whom advice was received: GPs: in 93 patients specialists: 100 patients Patients who received advice versus patients who walked for exercise: 151/216, 70% mostly nonspecific walking advice versus 113/216; 52% Where patients were advised to go for walking versus where patients walked: local neighborhood 84/151 56% versus 96/113; 85% on the treadmill 12/151, 8%; 9/113, 8% Referred to a physiotherapist 17/151 (11%) Quantity of walking advised versus adherence: to pain onset 36, 24% versus 30, 27% to maximal pain 22, 15% versus 24, 21% steps beyond pain onset 52, 34% versus 50, 44% ⩾3×/day 34, 23% versus 28, 25% <3×/day 21, 14% versus 29, 26% >3×/ week 24, 16% versus 32, 28% <3×/week 6, 4% versus 6, 5.3% 15 min and 30 min 53, 35%versus 55, 49% Mostly >30 min 22, 15%versus 23, 20% Supervised walking exercise: Supervision: once every 3–6 months visits to GP or specialist Persons reporting to receive: 36/133, 36% Duration mostly reported: >6 months (52/67 persons) Patients’ reported benefit: symptoms improved 53/113, 47% no change 46/113, 41% symptoms worsened 9, 8% |

||

| Müller-Bühl et al.34

Germany |

To document data about the participation of patients with IC in walking exercise therapy | Prospective non-experimental study | n = 166; age: mean = 71 years Diabetes: 25%; ABI: mean = 0.58; hypertension: 79%; ICD: mean = 94.5; ACD; 162.3; patients attending routine diagnosis and treatment for PAD and IC in a German hospital | Patients eligibility for SEPs Patients’ willingness to participate in SEPs Patients attendance in SEPs |

Total patients screened: 462 Patients eligible for walking therapy: 166, 36% Patients who indicated willingness to attend: 110, 66% Patients who actually started the program: 52, 31% Patients who attended regularly: 36, 26% |

There is still low patient attendance rate in walking therapy programs for IC in Germany. | |

| Kruidenier et al. 200935

The Netherlands |

To report the functioning of community-based SEPs at 1 year of follow up | Prospective cohort study | 349 patients referred for community

SEPs. Age: 58.6–74 years; men: 63%. BMI: 23.6–29.0; ABI 0.70; current smokers: 49%; hypertension: 76%; diabetes mellitus: 34%; hypercholesterolemia: 77%; coronary heart disease: 27%; cerebrovascular disease:14%; COPD: 14%; arthrosis: 5%; previous vascular intervention: 32% |

Patients eligibility for SEPs Patient willingness to participate in SEPs Patients attendance in SEPs |

Total number of patients referred for SEPs:

n = 349 272 patients who began a SEP 52 patients began at lower level 25 patients never started the program At 1 year follow up: patients who completed SEP: 129/272 (47.4%) patients who dropped out: 143/272 Reasons for dropping out: satisfaction with gained walking distance (n = 19) unsatisfying results (n = 26) lack of motivation (n = 22) (non) vascular intercurrent disease (n = 48) other reasons (n = 28) |

A SEP based in the community is as effective as a hospital- delivered SEP in improving walking distance with outcomes likely to persist after 3 months in patients with IC. However, it tends to have high dropout rates. | |

| Makris et al.36

International |

To evaluate the current international availability and use of SEPs | Online questionnaire survey |

n = 378; vascular surgeons from 43

countries Responses: Europe: 95%; England: 34%; Greece: 16% |

Response rate: 378/1673 (23%) | SEP availability SEP delivery |

Availability of SEPs per country: The Netherlands: 100% France: 67% Germany: 47% Italy: 38% UK: 36% Switzerland: 36% Spain: 11% Greece: 10% Internationally to SEP: 115 (30%) Referral to SEP: only 21/115 (18%) would refer all their patients to SEPs 50/115 (43%) would refer less than 50% Implementation of SEP: per session duration <1 h duration for SEP: 37% between 1 h and 2 h: 53% >2 h:10% total duration <3 months:23% between 3 months and 6 months: 57% >6 months: 21% Personnel running SEP: physiotherapists: 48% doctors: 37% Follow-up appointment at the end of SEP: 70% yes |

SEPs remained underutilized despite the overwhelming evidence of their effectiveness. |

| Shalhoub et al.37

UK |

To determine vascular surgeons’ access to SEPs, practices related to SEPs for patients with IC | Cross-sectional survey | n = 84; UK resident vascular surgeons | Response rate: 84/186 (45%) | SEPs availability and referral

information Patients eligibility SEP compliance SEP delivery Alternative prescriptions |

Access to SEPs: 20 (24%) Proportion of eligible patients referred for SEPs <50% of their patients: 46% of surgeon at least 50% of their patients: 54% of surgeons Compliance to SEP: <50% compliance: 58% of programs >50% compliance: 42% of programs Contraindications to SEPs: cardiac: 27% rest pain/tissue loss: 8% musculoskeletal/arthritis: 8% geography/transport/distance to hospital: 8% COPD/reduced PFTs/respiratory disorder: 8% employment constraints: 4% mobility constraints: 4% hypertension: 4% poor compliance: 4% others: 23% Per session duration: <1 h: 15% 1 h: 85 Session frequency: <1×/week: 10% 1×/week: 65% 2×/week: 20% 3×/week: 5% Total duration of program: <3 months: 20% 3 months: 55% 6 months: 20% Continuous: 5% Program leader: physiotherapist: 41% nurse: 48% doctor: 3% non-healthcare professional: 7% If no service, advice given: verbal: 63% leaflet: 34% demonstration: 3% If no service, existing obstacle: resource: 72% patient compliance: 9% belief: 2% other: 17% |

SEPs remained largely under-utilized. |

| Lauret et al.38

The Netherlands |

To document current opinion on vascular surgeons and fellows and vascular surgery professors about SEPs for PAD | Online or paper-based questionnaire survey |

n = 91 (51% of Dutch vascular

surgeons); vascular surgeon: 91%; men: 86%; age: ⩽50 years; 69%; non-academic hospital: 84% |

Referral information Attitude towards SEP indications Definition of success of conservative therapy |

Number of surgeons in agreement regarding the

usefulness of SEP In general: SEP is more effective than a single advice to walk: 100% SEP is the primary therapy for IC, in addition cardiovascular risk management: 97% Community-based SEPs and hospital-based SEPs are equally effective: 93% Physiotherapists’ feedback is useful to patient management 86% It is useful to continue SEPs if the patient does not improve in the first 3 months. For patients with IC: with ACD <100: 84% older than 80 years 82% after undergoing : 81% as a result of a significant iliac stenosis 71% with not-decompensated chronic heart failure 70% with a chronic pulmonary condition (like COPD): 66% In CLI, as adjunct to: angioplasty: 72% peripheral bypass surgery: 65% When do surgeons consider that a conservative management is successful in IC? satisfaction by the patient 63% improvement in pain-free or maximal walking ability 27% improvement in quality of life 3% improvement in ABI 3% no further decline in pain-free or maximal walking ability 2% adjustment of patient’s lifestyle 1.8 (2/109) improvement in ADL 1% |

Dutch vascular surgeons consider SEPs to be important in the management of PAD. They also believe that most conditions thought to be contraindications for SEPs are indeed additional indications for exercise recommendations. |

ABI, ankle-brachial index; ACD, anemia of chronic disease; ADL, activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; CLI, critical limb ischemia; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IC, intermittent claudication; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; PFT, pulmonary function test; PT, physiotherapist; SEP, supervised exercise programme.

Stage 5: collating, summarizing and reporting the results

A total of 102 records were identified through the searches. Following the screening process, eight records met the study inclusion criteria. The screening process and reasons for excluding studies are presented in Figure 1. Included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

The included studies were published between 2004 and 2017. All studies were from European countries. The Netherlands contributed the largest volume of literature (n = 4), followed by the UK (n = 2), and one study was from Germany (n = 1). There was also 1 international study which surveyed respondents from 43 European countries (although it reported collected data from only 9 countries due to response variability).36

Populations

Some studies had more than one population of interest. However, populations included vascular surgeons/vascular residents (n = 4), patients and/or service user/delivery (n = 3), and GPs and physiotherapists (n = 1).

Study design

According to the Littlewood and May classification39 all studies were primary research and were mostly cross-sectional observational surveys (n = 5), followed by cohort studies (n = 2), and a mixed-method study.

Focus/theme of the studies

The included studies fell broadly into three categories: (a) determining access, availability, practice, provision, and opinion regarding exercise for IC; this included surveys among vascular surgeons, vascular residents, physiotherapists, or patients (n = 5); (b) investigating the role of GPs and physiotherapists in noninvasive therapy, including exercise therapy programs for people with IC (n = 1); (c) documenting the functioning of routine exercise therapy programs for IC and/or patients’ participation in the program (n = 2).

Outcomes in included studies

Availability, access, and practices related to SEPs

Three studies reported on the availability of SEPs and access to them, and scoped responses from vascular surgeons.31,36,37 Results showed that across Europe, less than one in three vascular surgeons reported having access to SEPs to which to refer patients.36 Country-specific data indicated that all vascular surgeons in the Netherlands, most (67%) of those in France, and about 10% in Spain and Greece have access to SEPs to which to refer their patients.36 Data from the UK suggested improvements in the access of vascular surgeons to SEPs over the past decade (24% in 2009, 36% in 2012, and 41.6% in 2017), however the majority still did not have access to a SEP.31,36,37 When examined in terms of facility access, just about one in three (38.9%) vascular units in the UK reported having access to SEPs for UK NHS patients.31

Between 2011 and 2012 about 45% of vascular surgeons in Europe with access to SEP would refer less than 50% of their eligible patients, with only 18% saying they would refer all their patients.36 Almost half (46%) of UK vascular surgeons in 2009 reported referring less than 50% of their eligible patients to SEPs, with only 14% referring 100% of their patients.37 In a 2004 survey, although most (86%) GPs in the Netherlands indicated that they advised their patients with IC to exercise, 38% said they did not provide supervision or follow up as part of exercise therapy.32 Only a minority (15%) referred their patients to a physiotherapist for supervised exercise.32 Expectedly in this survey, only 8% of physiotherapists occasionally treated patients with IC.32 In a survey among patients 1 year later (between 2005 and 2006), Dutch patients with IC reported that they received advice to walk mainly from their vascular surgeons and GPs, with only 11% reporting being referred to a physiotherapist for supervised exercise.33 A survey in 2012, however, showed that almost all (about 97%) of vascular surgeons in the Netherlands reported referring more than 75% of their eligible patients for SEPs.38

Only one study investigated if follow-up visits were scheduled for patients who undertook SEPs.36 In this survey, 70.4% of vascular surgeons said they will bring back patients for follow up. Similarly, one study reported that the majority of vascular surgeons would judge the success of SEPs based on patients’ satisfaction, while improvement in walking distance was used by only 27% of vascular surgeons.38

Attitude to SEPs therapy

A study in the Netherlands reported that all vascular surgeons surveyed agreed that SEPs should be part of rehabilitation for IC, and that they are more effective than one-off unsupervised advice to walk (usual care).38 Also, a large majority of them (about 97%) agreed that SEPs are the primary treatment for IC, believed that community-based and hospital-based SEPs are equally effective (about 93%), and 60% will consider continuing their patients in SEPs beyond 3 months if patients do not show improvement.38

Patient engagement and adherence to exercise therapy

A 2009–2010 investigation of routine exercise therapy for IC in a German outpatient clinic reported that 69% of the patients either declined the invitation or did not turn up for any of the training sessions.34 This study also indicated that only 22% of patients attended regularly.34 Similarly, a 2009 survey of vascular surgeons in the UK NHS showed that, where SEPs are available, the majority of patients do not comply with recommendations: only 39% of them reported up to 50% of their patients taking SEPs or adhering to their SEP recommendations.37 Although patients’ adherence to SEPs had risen in 2017 (five in six vascular units recorded >90% completion), patients engagement was still a great challenge (only one in six of vascular units had up to 80% of referred patients starting a SEP).31 These units did not generally document information related to commencement and completion rates for home-based exercise therapy.31

A survey of Dutch patients with IC indicated that only 32% undertook SEPs.33 The majority (52%) walked for exercise mostly in the neighborhood, not reaching optimum walking intensity (only 44% walked through pain) or frequency (only 25% walked 3×/week).33

Personnel who deliver exercise program

Vascular surgeons in the UK reported that exercise therapy for IC whether home or hospital based was run by physiotherapists and specialist nurses with a few run by exercise and non-healthcare professionals.31,37 Also vascular surgeons across Europe indicated that the majority (48%) of SEPs in their countries were run by physiotherapists while 37% were run by doctors.36

Program types (hospital versus home based) and features of exercise programs

Regarding the site of exercise, one of the studies indicated that the majority of SEPs in the UK were delivered in hospital facilities.31 In contrast, the majority (70%) of Dutch patients with IC reported they received advice to walk at home.33 Hospital-based SEPs in the UK generally consisted of either a combination of aerobic and resistance exercises or aerobic exercise alone.31,37 Whilst 55–90% of the programs lasted for 30–60 min per session for 3 months, 65–80% ran as one session per week (65–80%).31,37 Across Europe the majority of SEP programs were run as 1–2 h/session (53%), and lasted between 3 months and 6 months, but the number of sessions undertaken in a week was not investigated.36

Common indications, contraindications and obstacles to exercise

Vascular surgeons’ attitude towards indications and contraindications for people with IC for participation in SEPs was reported by two studies from the Netherlands. The following comorbidities were cited as contraindications: mobility problems, hypertension, angina/ischaemic heart disease/ACS/myocardiac infarction, rest pain/tissue loss/critical limb ischaemia, musculoskeletal/arthritis,37 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/respiratory compromise,37,38 and significant iliac stenosis,38 In contrast, maximal walking distance <100 m or age >80 years were not considered contraindications. Also the majority of vascular surgeons would consider SEPs as adjunct therapy pre- or post-surgery.38 Factors cited as obstacles to making SEPs available to patients included resource challenge and patient compliance.37 Similarly, reasons for not attending SEPs in a German clinic included deficient patient motivation, travel distance, and the perception that exercise is physically demanding.34

Alternative services in place when a SEP is not available or feasible

The majority (75%) of patients in one study reported that they had received nonspecific advice to walk.33 Other reported alternatives included receiving specific instruction on how much walking should be carried out (43%)36 and receiving verbal advice or leaflets (30%).36,37

Discussion

The key aims of this systematic scoping review were to identify and map the body of literature related to routine provision of exercise for the treatment of IC. Findings provide an essential contribution to reflections and research on access, utilization and stakeholders’ perspectives on the guideline-recommended, noninvasive therapy for this patient population. Only including studies that reported on exercise in routine care was deliberate, while the vast majority of studies were excluded because they reported on trials and/or experimental studies of exercise interventions. The inclusion of only eight eligible studies underscores the paucity of literature on this topic. The overall trend showed that literature related to provision of exercise in routine care for persons with PAD and IC is relatively new (<14 years old), and nonexistent in the majority of countries in Europe and around the world.

Similarly, the overall volume of literature remained small despite the overwhelming evidence of the benefits and effectiveness of exercise therapy in experimental literature. Furthermore, the geographical location of studies highlighted the fact that the larger area of global health systems is not yet represented. For instance, the majority of the publications were from the Netherlands and UK, and no data were found originating from outside Europe. This may indicate that despite the fact that much research evidence supporting exercise as a treatment for IC is relatively old, research into practices related to the routine provision of exercise in healthcare systems is yet to be made a research priority. Paucity of research into the provision of exercise in the management of IC may also reflect the absence of this service in most public health systems around the world. For instance the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in the USA only gave a national coverage decision of supervised exercise therapy for PAD and IC in mid-2017.40 Until this decision, there was no national coverage reimbursement for supervised exercise therapy treatment for patients with PAD and IC.

Although vascular surgeons in parts of Europe generally recognize SEPs to be beneficial to patients with PAD and IC, they do not often refer their patients for SEPs due to the unavailability of programs or lack of access. Where programs are available and accessible, challenges related to patients’ engagement and adherence were significant causes of suboptimal implementation, and may be some of the reasons why about 45% of surgeons within Europe refer less than 50% of their eligible patients to SEPs.36 Another important concern is that routine SEPs may not be complying with the best practice recommendations in terms of frequency. For instance, the frequency of the sessions for the greater majority of SEPs in the UK is once a week,31,37 and this arguably raises a question about the efficacy of the programs. The included studies in this review did not research why the hospitals are only putting on the sessions once per week. However, there is an opinion that the commissioners in the UK NHS are reluctant to fund SEPs and best medical therapy in the majority of patients with IC. Certainly, this highlights the need to adequately incentivize and reward hospitals to prioritize supervised exercise and best medical therapy as a first option prior to surgical intervention.21 Similarly, barriers to exercise in patients with PAD and IC are multidimensional, including individual level factors (e.g. poor health literacy and comorbid health concerns), disease-specific factors (e.g. claudication pain), and availability or otherwise of environmental and social enablers,41,42 and worth considering when planning exercise for patients.

Despite seeing no improvement in the walking distances of patients at 12 weeks, 60% of providers considered continuing SEPs. Some patient-specific factors may require a longer duration than 12 weeks for important benefits to be accrued. In addition, there is evidence of benefits to overall cardiovascular health and quality of life of exercise in patients with PAD and IC, separate from any improvement in walking ability measures.43 Indeed, it is the potential improvement in cardiovascular health and the overall potential secondary prevention benefits that is central to exercise therapy recommendations in patients with PAD and IC.43,44 Therefore, considering continuing SEPs in the absence of improvement in walking distances is recommended.40

Some limitations regarding the review findings need to be considered. First, although our search string aimed to include data from all regions of the world, it was limited to peer-review, published English language literature. Literature in other languages may not have been retrieved, and retrieved data were limited to a few countries within Europe. Second, poor response rates in the surveys of vascular surgeon in the UK (24.6%) and Europe (23%) meant that caution should be applied when generalizing findings to all the UK or Europe.

Conclusion

A number of conclusions can be drawn. SEPs are not always utilized by referring healthcare providers. Although health professionals recognize that SEPs are useful and should be available and accessible to patients with IC, available evidence indicates that SEPs are not always available or accessible to patients. When available, the sustainability of continual provision of SEPs in the continuum of chronic disease pathway of IC may not be feasible due to the resource and time cost to both the patient and the health system. Key areas of focus for integrating and implementing exercise recommendations to routine clinical practice in people with IC are needed. It may be important to understand factors such as barriers and enablers to exercise in individuals with PAD and IC. Although some may be similar across health systems, many may be specific to each health system and need to be investigated individually. It will be beneficial to understand why health systems do not fund SEPs for PAD and IC despite the overwhelming evidence for the clinical and cost effectiveness. This may be important to further understanding of patient, environmental, and behavioral constructs worth considering in developing relevant and patient-focused intervention to increase the availability of, and access to exercise programs, as well as to encourage the uptake and adherence to exercise in people with PAD and IC.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Exercise_provision_-_PRISMA_2009_checklist for Exercise therapy in routine management of peripheral arterial disease and intermittent claudication: a scoping review by Ukachukwu O. Abaraogu, Onyinyechukwu D. Abaraogu, Philippa M. Dall, Garry Tew, Wesley Stuart, Julie Brittenden and Chris A. Seenan in Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease

Supplemental material, Search_Strategy_-_Routine_Exercise_provision for Exercise therapy in routine management of peripheral arterial disease and intermittent claudication: a scoping review by Ukachukwu O. Abaraogu, Onyinyechukwu D. Abaraogu, Philippa M. Dall, Garry Tew, Wesley Stuart, Julie Brittenden and Chris A. Seenan in Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease

Footnotes

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: UOA received funding from the University of Nigeria through the TETFund for a PhD at Glasgow Caledonian University. This scoping review is part of a work towards the award of his PhD. The University of Nigeria has no input on the interpretation or publication of study results. Glasgow Caledonian University provided material support in the conduct and management of this scoping review but had no input on the interpretation or publication of results.

Authors’ Note: Onyinyechukwu D. Abaraogu is also affiliated to Physiotherapy Department Drum Chapel Health Centre NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Glasgow United Kingdom.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ORCID iD: Ukachukwu O. Abaraogu  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1967-1459

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1967-1459

Author contributions: Conception and initial drafting of the manuscript (UOA); design, data collection, studies eligibility assessment, data extraction, and analysis (UOA and ODA); data visualization and validation (PMD, GT, WS and JB, CAS); supervision (PMD, CAS); critical revision of the results for important intellectual content (UOA, PMD, GT, WS, JB, CAS). All authors read, provided feedback and approved the final version of the manuscript. UOA is the guarantor.

Ethics: This research made use of already published papers and did not require ethics approval.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Ukachukwu O. Abaraogu, Department of Physiotherapy and Paramedicine, School of Health and Life Sciences, Glasgow Caledonian University, Room 226 Govan Mbeki Building, Cowcaddens Road, Glasgow, Scotland G4 0BA, UK.

Onyinyechukwu D. Abaraogu, Department of Medical Rehabilitation, University of Nigeria, Enugu, Nigeria

Philippa M. Dall, Department of Physiotherapy and Paramedicine, Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, UK

Garry Tew, Department of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation, Northumbria University, Newcastle, UK.

Wesley Stuart, Vascular Surgery, Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, Glasgow, UK.

Julie Brittenden, Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK.

Chris A. Seenan, Department of Physiotherapy and Paramedicine, Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, UK

References

- 1. Criqui MH, Aboyans V. Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease. Circ Res 2015; 116: 1509–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McDermott MM, Liu K, Greenland P, et al. Functional decline in peripheral arterial disease: associations with the ankle brachial index and leg symptoms. JAMA 2004; 292: 453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McDermott MM, Ferrucci L, Liu K, et al. Leg symptom categories and rates of mobility decline in peripheral arterial disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58: 1256–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Inglis SC, Lewsey JD, Lowe GDO, et al. Angina and intermittent claudication in 7403 participants of the 2003 Scottish Health Survey: Impact on general and mental health, quality of life and five-year mortality. Int J Cardiol 2013; 167: 2149–2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sieminski DJ, Gardner AW. The relationship between free-living daily physical activity and the severity of peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Vasc Med 1997; 2: 286–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. dos Anjos Souza, Barbosa JP, Henriques PM, de Barros MVG, et al. Physical activity level in individuals with peripheral arterial disease: a systematic review. J Vasc Bras 2012; 11: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016. AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American college of cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2017; 135: e726–e779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McDermott MMG, Kibbe MR. Improving lower extremity functioning in peripheral artery disease: exercise, endovascular revascularization, or both? JAMA 2017; 317: 689–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aherne T, McHugh S, Kheirelseid EA, et al. Comparing supervised exercise therapy to invasive measures in the management of symptomatic peripheral arterial disease. Surg Res Pract 2015; 2015: 960402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fokkenrood H, Bendermacher B, Lauret G, et al. Supervised exercise therapy versus non-supervised exercise therapy for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 8: CD005263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guidon M, McGee H. One-year effect of a supervised exercise programme on functional capacity and quality of life in peripheral arterial disease. Disabil Rehabil 2013; 35: 397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016. AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: executive summary. Circulation 2016; 63: CIR.0000000000000470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fowkes F, Armitage M, Belch J, et al. Diagnosis and management of Peripheral Arterial Disease. A National Clinical Guideline. SIGNScottish Intercoll Guidel Netw 2006; 89: 41. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tendera M, Aboyans V, Bartelink M-L, et al. ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral artery diseases. Eur Heart J 2011; 32: 2851–2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fokkenrood HJP, Bendermacher BLW, Lauret GJ, et al. Supervised exercise therapy versus non-supervised exercise therapy for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 8: CD005263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gardner AW, Parker DE, Montgomery PS, et al. Step-monitored home exercise improves ambulation, vascular function, and inflammation in symptomatic patients with peripheral artery disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Heart Assoc 2014; 3: e001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McDermott MM, Liu K, Guralnik JM, et al. Home-based walking exercise intervention in peripheral artery disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 310: 57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Askew CD, Parmenter B, Leicht AS, et al. Exercise & Sports Science Australia (ESSA) position statement on exercise prescription for patients with peripheral arterial disease and intermittent claudication. J Sci Med Sport 2014; 17: 623–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Layden J, Michaels J, Bermingham S, et al. Diagnosis and management of lower limb peripheral arterial disease: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2012; 345: e4947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lane R, Harwood A, Watson L, et al. Exercise for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 12: CD000990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Popplewell MA, Bradbury AW. Why do health systems not fund supervised exercise programmes for intermittent claudication? Eur J Vas Endovasc Surg 2014; 48: 608–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jivegård L, Nordanstig J. Re: “Why do health systems not fund supervised exercise programmes for intermittent claudication.” Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2015; 50: 262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee S. Evaluating serviceability of healthcare servicescapes: service design perspective. Int J Des 2011; 5: 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mosadeghrad AM. Factors influencing healthcare service quality. Int J Heal Policy Manag 2014; 3: 77–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bandura A. A social cognitive theory of personality. In: Pervin L, John O. (ed.) Handbook of personality. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Publications, 1999, pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gommans L, Teijink J. Attitudes to supervised exercise therapy. Br J Surg 2015; 105: 1153–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005; 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010; 5: 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169: 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015; 13: 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harwood AE, Smith G, Broadbent E, et al. Access to supervised exercise services for peripheral vascular disease patients: which factors determine the current provision of supervised exercise in the UK? R Coll Surgen Bull 2017; 99: 207–211. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bartelink M-LEL, Wullink M, Stoffers HEJH, et al. Walking exercise in patients with intermittent claudication not well implemented in Dutch primary care. Eur J Gen Pract 2005; 11: 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bartelink M-L, Stoffers HEJH, Biesheuvel CJ, et al. Walking exercise in patients with intermittent claudication. Experience in routine clinical practice. Br J Gen Pract 2004; 54: 196–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Müller-Bühl U, Engeser P, Leutgeb R, et al. Low attendance of patients with intermittent claudication in a German community-based walking exercise program. Int Angiol 2012; 31: 271–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kruidenier LM, Nicolaï SP, Hendriks EJ, et al. Supervised exercise therapy for intermittent claudication in daily practice. J Vasc Surg 2009; 49: 363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Makris GC, Lattimer CR, Lavida A, et al. Availability of supervised exercise programs and the role of structured home-based exercise in peripheral arterial disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2012; 44: 569–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shalhoub J, Hamish M, Davies AH. Supervised exercise for intermittent claudication - an under-utilised tool. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2009; 91: 473–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lauret GJ, van Dalen HC, Hendriks HJ, et al. When is supervised exercise therapy considered useful in peripheral arterial occlusive disease? A nationwide survey among vascular surgeons. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2012; 43: 308–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Littlewood C, May S. Understanding physiotherapy research. Newcastle upon Tyne: Canbridge Scholars Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jensen TS, Joseph C, Ashby L, et al. Decision memo for supervised exercise therapy (SET) for symptomatic peripheral artery disease (PAD). CAG-00449N. Baltimore: US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abaraogu U, Ezenwankwo E, Dall P, et al. Barriers and enablers to walking in individuals with intermittent claudication: a systematic review to conceptualize a relevant and patient-centered program. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0201095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Abaraogu UO, Ezenwankwo EF, Dall PM, et al. Living a burdensome and demanding life: a qualitative systematic review of the patients experiences of peripheral arterial disease. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0207456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Novakovic M, Jug B, Lenasi H. Clinical impact of exercise in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Vascular 2017; 25: 412–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Conte MS, Pomposelli FB, Clair DG, et al. Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines for atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the lower extremities: management of asymptomatic disease and claudication. J Vasc Surg 2015; 61(3 Suppl.): 2S–41S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Exercise_provision_-_PRISMA_2009_checklist for Exercise therapy in routine management of peripheral arterial disease and intermittent claudication: a scoping review by Ukachukwu O. Abaraogu, Onyinyechukwu D. Abaraogu, Philippa M. Dall, Garry Tew, Wesley Stuart, Julie Brittenden and Chris A. Seenan in Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease

Supplemental material, Search_Strategy_-_Routine_Exercise_provision for Exercise therapy in routine management of peripheral arterial disease and intermittent claudication: a scoping review by Ukachukwu O. Abaraogu, Onyinyechukwu D. Abaraogu, Philippa M. Dall, Garry Tew, Wesley Stuart, Julie Brittenden and Chris A. Seenan in Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease