Abstract

The factors that affect the interval to ovulation, the type of ovulated dominant follicle (DF), and the cause of anovulation after prostaglandin (PG) treatment were investigated. Nine cows were assigned to six groups (54 cows in total) but the group size was later fixed at eight cows (48 in total). They received 25 mg tromethamine dinoprost as dinoprost on Day 6 (Group D6), Day 7 (Group D7), Day 8 (Group D8), Day 9 (Group D9), Day 10 (Group D10), or Day 11 (Group D11) after natural ovulation (Day 0). If the DF did not ovulate, then the cow was assigned to Group NO. In Group D6, the 1st DF ovulated in all cows 4 days after PG treatment, whereas in Groups D9, D10, and D11, the 2nd DF ovulated in all cows 4 to 7 days after PG treatment. In 10 cows, the DF did not ovulate, and late anovulation was significantly higher in Group D6 cows than in Group D11 cows. The progesterone (P4) levels decreased to less than 1 ng/ml in all groups on the day after PG treatment. The estradiol-17β (E2) levels began to increase after PG treatment and peaked at 2 days before ovulation in the cows that ovulated. In anovulated cows, E2 tended to be higher and there was no clear E2 peak in some cows. These results indicated that the number of days to ovulation, the type of ovulated DF, and anovulation were affected by factors that were associated with the DF when it was producing E2.

Keywords: cattle, dominant follicle, estradiol, progesterone, prostaglandin

The reproductive performance of lactating dairy cows is a major factor affecting herd profitability, which means that calving intervals should be kept within a targeted timespan. To attain this goal, accurate and high percentage estrus detection are critically important [25]. The expression of estrus can be influenced by many different factors, such as heredity, the number of days postpartum, lactation number, milk production, nutrition, season, housing, herd size, and health [37]. Milk production per cow is increasing year on year, and herd sizes are getting larger [37]. A negative association between high milk production and the expression of behavioral estrus has been observed [11,12,13, 23, 27], and the percentage of standing estrus and the duration of estrus have decreased over the past 50 years [14, 51]. For these reasons, it is becoming difficult to accurately detect estrus. Inadequate or inaccurate detection of estrus are critical factors that are responsible for poor reproductive performance in dairy cows [37, 52].

To deal with this problem, several methods for estrous or ovulation synchronization have been devised [8, 26, 34]. A well-established method for estrous synchronization was to regress the corps luteum (CL) using prostaglandin F2α or its analogue (PG) [26, 53]. However, a major problem with this method is the lack of a consistent time point to induce estrus [26], with the number of days from PG treatment to estrus varying from 2–9 days [30]. In addition, it has been reported that PG may fail to induce luteolysis or ovulation [47]. For these reasons, estrus synchronization cannot be used to predict when timed artificial insemination (TAI) needs to take place [2, 3, 53].

Subsequently, ovulation synchronization using PG and GnRH (Ovsynch) has been developed. The advantage of this method is that TAI can take place without estrous detection [8, 30, 34, 35, 52, 53]. However, Ovsynch needs to be initiated on Day 5 to 12 of the estrous cycle to be effective [31, 50, 52]. Otherwise, the conception rate after TAI is not high due to incomplete CL regression after PG treatment and poor ovulatory responses to GnRH [10, 28, 46, 49, 53]. Previous studies have reported using a pre-synchronization strategy to increase the conception rate by Ovsynch. In this method, cows receive two PG treatments 14 days apart and both are administered at least 14 days before the initiation of Ovsynch [8, 32, 46, 52]. The most important requirement for pre-synchronization is that the cows need to recover their ovarian activity after parturition [7, 16]. Ovsynch is known to induce cyclicity in a high percentage of anovular cows [16]. Therefore, Souza et al. replaced the pre-synchronization strategy used with Ovsynch and suggested a single method to increase fertility using TAI, which they called the Double-Ovsynch method [42]. However, Double-Ovsynch requires a long period of time from initiation to TAI, is expensive, and is labor intensive. This has indicated that no obvious economic benefit has been identified [43, 44].

Although estrous synchronization by luteolysis using PG is inconsistent, when PG treatment is followed by estrous detection, the conception rate tends to be higher [3, 4, 21]. The low conception rate in cows after TAI with PG is most likely related to the greater variation in the timing of ovulation following PG treatment [4]. If the time of ovulation can be predicted more correctly after PG treatment, estrous synchronization by PG will become more useful because it is simple and economical. In particular, it seems to be more suitable on farms where the herd size is not large. It has been suggested that the timing of PG treatment relative to stage that a follicular wave is in a major cause of variation in the subsequent onset of estrus or ovulation [40] and the type of ovulated follicle (1st, 2nd, or 3rd wave dominant follicle) [30]. Furthermore, ovulation does not occur in some cows, even when PG treatment induces apparently normal estrus [45]. In this study, we investigated the basic factors that affected the interval from PG treatment to ovulation and the type of ovulated follicle produced. We also attempted to clarify the reasons why PG treatment failed to induce ovulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Nine Holstein cows (Cow numbers 1–9) were used per group. Their ages were >4 years (5.8 ± 0.6; mean ± SD). The animals were housed in a tie-stall barn at Azabu University, Japan. None of these cows had been inseminated after their last parturition and had been milked because they were kept for educational purposes. The parities of the cows were unknown and ≥2 years had passed since their last parturition. Rectal examination of the cows confirmed that there were no clinical abnormalities of the uterus or any abnormal vulvar discharge. All experiments were carried out with approval from the Ethics Committee of Azabu University.

Ultrasound scanning

A real-time ultrasonograph (Model HS-2100V; Honda Electronics Co., Ltd., Toyohashi, Japan) equipped with a 10-MHz transrectal linear transducer was used to monitor the daily changes in follicles and the CL between 11:00 and 14:00. Natural ovulation (Day 0) was defined as being when the DF appeared in the ovary at estrus and was confirmed to have disappeared by transrectal palpation and real-time ultrasonography. The 1st wave DF (1st DF) was the follicle that grew the largest after natural ovulation, and the 2nd wave DF (2nd DF) was the follicle that grew the largest after the 1st DF had regressed. The size of the follicle was the mean of the long diameter and short diameter.

Treatment with PG

Nine cows were randomly assigned to six groups after natural ovulation until the number of cows in each group reached eight (or 48 cows in total actually tested). The cows in each group were administered PG (25 mg tromethamine dinoprost as dinoprost, Pronalgon F; Zoetis JP, Tokyo, Japan) intramuscularly on Day 6 (Group D6), Day 7 (Group D7), Day 8 (Group D8), Day 9 (Group D9), Day 10 (Group D10), or Day 11 (Group D11) after natural ovulation. After PG treatment, the ovaries were monitored from Day 1 to Day 18 and ovulation of the DF was confirmed. The cows were assigned into each group only one time. If both the 1st DF and the 2nd DF did not ovulate after PG treatment, then the cows were assigned into Group NO. We recorded the type of ovulated DF (1st DF or 2nd DF) and how many days it took to ovulate after PG treatment. The interval between each PG treatment was 47.9 ± 3.8 days (mean ± SEM, n=50), and the range was 27–163 days.

Blood sampling

A vacuum-type heparinized tube was used to collect each blood sample from the tail vein. The plasma was separated by centrifugation (3,500 × g for 10 min) and stored at −30°C until the progesterone (P4) and estradiol-17β (E2) concentrations in the plasma were determined.

Hormone analysis

The P4 concentrations in the plasma were determined using the enzyme immuno-assay (EIA) methods described previously [19]. The E2 levels in plasma were also measured using the EIA methods as described by Isobe [18], with some modifications. Briefly, 75 µl of extracted estradiol-17β standard or the sample and 25 µl of the 1:10,000 diluted estradiol-17β antibody (ab215528, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) were applied to the wells of plates that had been previously coated with goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Millipore; Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA). After 1 hr incubation, 25 µl of 1:2,500 diluted estradiol-6-CMO-HRP antigen (East Coast Bio, Inc., North Berwick, ME, USA) was added to the wells. The plate was incubated for another hour and then washed six times. The substrate solution was applied to the wells, and then, they were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 1 M H3PO4. The optical density was calculated at 450 nm. Sensitivity was 1.6 pg/ml for E2 and 0.5 ng/ml for P4. The intra-assay and inter-assay CVs were 11.4% and 6.7% for E2 and 8.6% and 3.2% for P4, respectively.

Data analysis

We compared the number of days from PG treatment to ovulation, P4 from 1 day before to 3 days after PG treatment, E2 after PG treatment, and the size of the 1st DF among the groups (ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test). Furthermore, the incidence rate of anovulation in Group NO was compared among the individual cows and among the days when PG was administered (χ2 test followed by Fisher’s exact test). The values are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean and were considered to be statistically significant at the P<0.05 level.

RESULTS

Ovulated DFs and the number of days from PG treatment to ovulation

Out of a total of 48 ovulated cases, 22 cases (45.8%), 16 cases (33.3%), 9 cases (18.8%), and 1 case (2.1%) ovulated 4 days, 5 days, 6 days, and 7 days after PG treatment, respectively.

The type of ovulated dominant follicle in each group is shown in Table 1. In Group D6, the 1st DF ovulated in all cows. In Group D7 and Group D8, the 1st DF ovulated in four or five cows, and the ovulated DF was the same in seven cows. The results showed that there were four cows in which the 1st DF ovulated in Group D7 and Group D8. Again, there were three cows in which the 2nd DF ovulated in Group D7 and Group D8. In Groups D9, D10, and D11, the 2nd DF ovulated in all cows.

Table 1. Number of days from prostaglandin treatment to ovulation.

The relationship between the number of days from PG treatment to ovulation and the ovulated follicle is also shown in Table 1. In cases when the 1st DF ovulated, all of them ovulated 4 days after PG treatment. In cases when the 2nd DF ovulated, ovulation occurred between 4–7 days after PG treatment. The number of days from PG treatment to the 2nd DF ovulation in Group D7 was the longest (6.0 ± 0.4; mean ± SEM). It decreased as the PG treatment day became later, and it was the shortest in Group D11 (4.9 ± 0.2). There were significant differences between the days when the 1st DF ovulated (P<0.05) in the cases where the 2nd DF ovulated in Group D7 and Group D9.

Size of the 1st DF

The size of the 1st DF at PG treatment and 3 days after PG treatment in each group is shown in Table 2. Although the size of the 1st DF at PG treatment in Groups D9 and D10 tended to be large, there were no significant differences among the groups except for Group 11. The 1st DF in Group D11 was the smallest in size, and there were significant differences between Group D11 and Group D10. The sizes of the 1st DF at 3 days after PG treatment in the groups where the 1st DF ovulated and in Group NO were significantly larger than those in the groups where the 2nd DF ovulated. Furthermore, the size of the 1st DF in the groups where the 1st DF ovulated and in Group NO became larger 3 days later. However, the size of the 1st DF in the groups where the 2nd DF ovulated was smaller, and there were significant differences between the time of PG treatment and at 3 days later among Group D9, Group D10, and Group D11. The sizes of the 2nd DF at PG treatment and 1 day before ovulation in groups where the 2nd DF ovulated are also shown in Table 2. The 2nd DF was not observed at PG treatment in many cows (20/31; 64.5%). Although the size of the 2nd DF tended to be larger as the day of PG treatment became later, there was no clear size tendency among any of the groups. Furthermore, there were no significant differences among the groups for the size of the 2nd DF at 1 day before ovulation

Table 2. Size of 1st and 2nd dominant follicles (mm).

| Ovulated follicle | 1st DF at PGc) | 1st DF 3 days after PG | 2nd DF at PG (n) | 2nd DF before OVd) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group D6 | 12.2 ± 0.5i) | 15.5 ± 0.6g,j) | ― | ― | |

| 1st DFa) | Group D7 | 13.2 ± 1.0 | 15.8 ± 1.2g) | ― | ― |

| Group D8 | 12.9 ± 1.0 | 14.8 ± 1.9g) | ― | ― | |

| Group D7 | 12.0 ± 1.0 | 11.6 ± 0.4h) | (0) | 12.4 ± 0.2 | |

| Group D8 | 10.9 ± 0.8 | 10.6 ± 1.9h) | 6.0 (1) | 11.8 ± 1.1 | |

| 2nd DFb) | Group D9 | 14.0 ± 1.5k) | 10.0 ± 0.7h,l) | 8.3 ± 0.8 (3) | 13.2 ± 0.4 |

| Group D10 | 14.1 ± 0.9e,m) | 10.1 ± 0.9h,n) | 7.5 ± 0.8 (2)q) | 12.8 ± 0.5 | |

| Group D11 | 11.6 ± 0.5f,o) | 7.9 ± 0.8h,p) | 9.2 ± 0.6 (5)r) | 13.3 ± 0.4 | |

| Anovulation | Group NO | 12.5 ± 0.4 | 13.3 ± 0.9g) | ||

a) 1st wave dominant follicle. b) 2nd wave dominant follicle. c) Prostaglandin treatment. d) Ovulation. Data are expressed as means ± standard error. Groups with superscripts e and f; g and h; i and j; k and l; m and n; o and p; and q and r were significantly different from each other (P<0.05).

Incidence rates of anovulation

By the time all six groups had eight cows each, there were 10 cases in which neither the 1st DF nor the 2nd DF ovulated (10/58; 17.2%). The anovulation incidence rate was different among individuals. The highest rate was in Cow No. 2 (4/5; 80.0%), and it was significantly higher than in the other cows except for Cow No. 6 (P<0.05) (Table 3). Furthermore, the anovulation incidence rate was different among the days when PG was administered, and the earlier the day on which PG was administered, the higher the anovulation incidence rate. The highest rate was on Day 6 (4/12; 33.3%), and it was significantly higher than on Day 11 (P<0.05) (Table 3). Anovulated DFs maintained their size for a few days and then regressed, or they increased their size and became like cystic follicles. In those cases, a new DF did not develop very quickly.

Table 3. Anovulation incidence rates.

| Cow No. | % | PG daya) | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cow No. 1 | 14.3c) | (1/7) | Day 6 | 33.3d) | (4/12) |

| Cow No. 2 | 80.0b) | (4/5) | Day 7 | 20.0 | (2/10) |

| Cow No. 3 | 0c) | (0/6) | Day 8 | 20.0 | (2/10) |

| Cow No. 4 | 0c) | (0/6) | Day 9 | 11.1 | (1/9) |

| Cow No. 5 | 14.3c) | (1/7) | Day 10 | 11.1 | (1/9) |

| Cow No. 6 | 37.5 | (3/8) | Day 11 | 0e) | (0/8) |

| Cow No. 7 | 14.3c) | (1/7) | |||

| Cow No. 8 | 0c) | (0/6) | |||

| Cow No. 9 | 0c) | (0/6) | |||

| Total | 17.2 | (10/58) | Total | 17.2 | (10/58) |

a) Day when prostaglandin was administrated. The values in the same column with different letters as superscripts are significantly different (P<0.05). Groups with superscripts b and c; and d and e were significantly different from each other (P<0.05).

Changes in P4 and E2

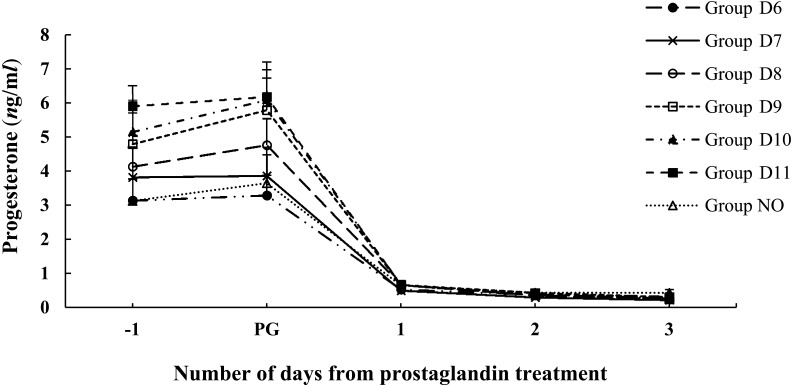

The changes to P4 in each group from 1 day before to 3 days after PG treatment are shown in Fig. 1. The P4 level was more than 1 ng/ml at 1 day before and on the day of PG treatment in all groups. Although the levels tended to be higher as the day when PG was administered got later, there were no significant differences among the groups. The P4 levels decreased to less than 1 ng/ml on the day after PG treatment in all groups.

Fig. 1.

Mean ± SEM P4 concentration between 1 day before and 3 days after PG treatment: Group D6 (●); Group D7 (×); Group D8 (○); Group D9 (□); Group D10 (▲); Group D11 (■); Group NO (Δ). PG, PG treatment. P4, progesterone.

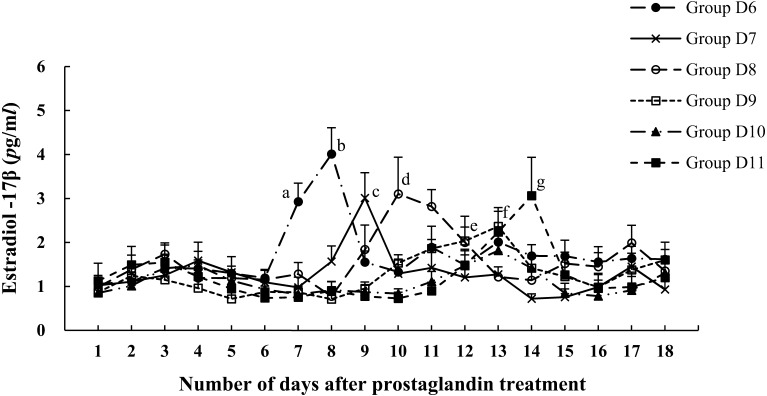

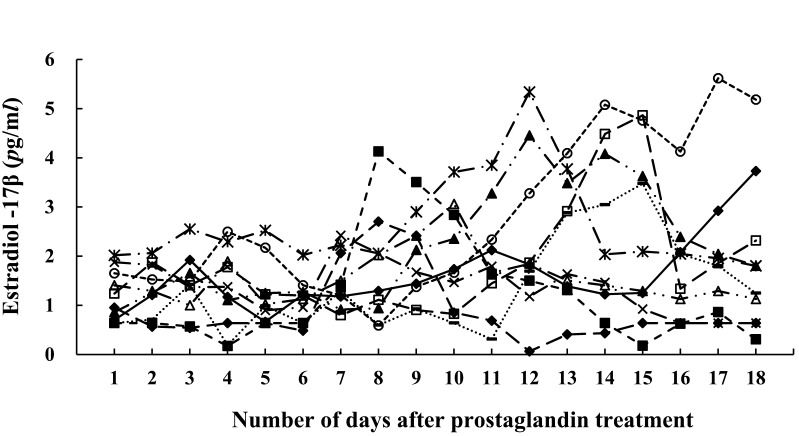

The changes to E2 in each group are shown in Fig. 2. The E2 levels fluctuated around 1 pg/ml, but then began to increase rapidly after PG treatment and peaked 2 days after PG treatment in Groups D6, D7, and D8. However, the peak occurred at 4 days after PG treatment in Group D9, and 3 days after PG treatment in Groups D10 and D11. The E2 peak occurred 2 days before ovulation in 40 out of 48 cows. Figure 3 shows the change in E2 after PG treatment in Group NO. Although E2 was around 1 to 2 pg/ml before PG treatment, it tended to increase and maintain a high value after PG treatment. Furthermore, there was no clear peak in some cows.

Fig. 2.

Mean ± SEM E2 concentration after PG treatment: Group D6 (●); Group D7 (×); Group D8 (○); Group D9 (□); Group D10 (▲); Group D11 (■). Significant differences between groups: a-The E2 concentration at this time point for Group D6 is significantly different from all other groups; b-The E2 concentration at this time point for Group D6 was significantly different from all other groups; c-The E2 concentration at this time point for Group D7 was significantly different from all other groups; d-The E2 concentration at this time point for Group D8 was significantly different from all other groups; e-The E2 concentration at this time point for Group D9 was significantly different from Groups D7, D10, and D11; f-The E2 concentration at this time point for Group D10 was significantly different from Groups D7 and D8; g-The E2 concentration at this time point for Group D11 was significantly different from all other groups (P<0.05).

Fig. 3.

E2 concentration after PG treatment in Group NO. E2, estradiol-17β.

DISCUSSION

The type of follicle that ovulated and the number of days from PG treatment to ovulation were affected by the day when PG was administered. Ovulation did not occur in 10 cases. The factors that affected these results may be due to the CL, the follicle, or both. Furthermore, due to PG being administrated after natural ovulation following natural CL regression, and because the mean interval between each PG treatment was 47.9 days, it does not seem that repeated PG treatment affected the development of follicles or ovulation.

The range for the time to estrus is due in part to the difference in the regression rate of the CL among the cows after the PG treatment had been administered [4, 22, 52]. At natural ovulation, P4 decreases to below 1 mg/ml, and after 2–3 days, the CL begins to regress in parous cows [39]. However, because regression of the CL was induced by PG treatment in this study, P4 decreased to around 1 ng/ml or less in all groups the day after PG treatment, which was consistent with the findings in previous studies [17, 47, 48]. Furthermore, there were no differences between the P4 values before and after PG treatment among the groups, including Group NO. These results suggested that the CL factors could be eliminated.

The interval from PG treatment to ovulation is also related to the time required to develop an ovulatory follicle [4, 22]. When the P4 concentration in the blood decreases as a result of CL regression, the increased pulsatile secretion of gonadotropins causes the DF to mature and secrete E2 [4]. This resulting E2 elevation in the blood triggers a preovulatory LH surge within 12–20 hr [5, 9]. Ovulation occurs 30 hr after the LH surge [20], which means that ovulation will occur about 2 days after the elevation in E2. In this study, most ovulated cows had a clear E2 peak at 2 days before ovulation. The E2 peak in Groups D6, D7, and D8 occurred 2 days after PG treatment. The results showed that when a follicle that can immediately secret E2 exists, P4 decreases and E2 begins to rise on the day after PG treatment, E2 reaches a peak 2 days after PG treatment, and the follicle ovulates 4 days after PG treatment. This explains why all 1st DFs ovulated 4 days after PG treatment in this study. The results suggest that the interval from PG treatment to ovulation is related to the ability of the follicle to produce E2. The reason that the E2 peak occurred 3 or 4 days after PG treatment in Groups D9, D10, and D11 may be that the 1st DF lost its dominance and could not produce E2, but the 2nd DF may have taken some time to develop to the point where it could produce E2.

In Group D6, the 1st DF ovulated 4 days after PG treatment in all cows. However, the 1st DF did not ovulate in half of the cows in Groups D7 and D8, and in any cow in Group D9. This means that the 1st DF could not secrete enough E2 to induce the LH surge in half of the cows in Groups D7 and D8 or in any cow in Group D9, and that the 1st DF loss of dominance had occurred on Day 8 or Day 9. Although there were no differences in the sizes of the 1st DF at the time of PG treatment among any group other than Group D11, at 3 days after PG treatment, the 1st DF size had become larger in cows in which the 1st DF ovulated, but it had become smaller in cows in which the 2nd DF ovulated. This means that the 1st DF in cows in which the 2nd DF ovulated became atretic. Mihm et al. reported that the 1st DF loses its dominance between Day 6 and Day 8 [29], and Adams et al. reported that atresia of the 1st DF occurred between Day 8 and Day 9 [1]. When PG is administered to cows that have an atretic DF, then that particular DF cannot ovulate, and another follicle will develop and ovulate [17].

In Groups D7 and D8, the ovulated DF was the same in seven out of eight cows. This suggested that the time that atresia of the 1st DF begins was determined by the individual cow. Kastelic et al. reported that all heifers (6/6) in which the 1st DF ovulated when PG was administered on Day 8 had two wave estrous cycles [22]. In this study, the cows in which the 1st DF ovulated might have had two wave estrous cycles, and the cows in which the 2nd DF ovulated might have had three wave estrous cycles.

In cases where the 2nd DF ovulated, the ovulation occurred over 4–7 days after PG treatment, and the E2 peak occurred 2 days before ovulation. Furthermore, the number of days between PG treatment and ovulation decreased as the PG treatment day got later. This indicated that the time needed for the 2nd DF to acquire the ability to generate the peak E2 levels in order to induce the LH surge is affected by the day of PG treatment. The interval from PG treatment to estrus or the LH surge is related to the time required to develop an ovulatory follicle [4, 22], and the number of days from PG treatment to ovulation is affected by the degree of maturation of the 2nd DF at the time of PG treatment [20]. If the PG treatment was delayed until after Day 12, then the maturation stage of the 2nd DF at the time of PG treatment was more advanced and the number of days to ovulation of the 2nd DF after PG treatment approached 4 days, which was the same as for the 1st DF ovulation. However, the 2nd DF was not observed at PG treatment in many cows in this study. Previous studies have shown that the emergence of the 2nd DF does not occur until Day 8 to Day 10 [1]. Therefore, the number of days to ovulation of the 2nd DF after PG treatment cannot be predicted from the size of the 2nd DF when PG treatment is administered.

In this study, ovulation did not occur in 10 cases after PG treatment, and the next DF took some time to develop, which confirmed the results of previous studies [47]. In the cows in which ovulation did not occur, P4 decreased immediately, which was similar to the ovulated cows after PG treatment. However, some cows did not show the E2 peak that was seen in the ovulated cows after PG treatment. Increasing E2 and decreasing P4 after luteolysis stimulates the LH pulse frequency, which results in a large preovulatory LH surge [1]. This suggests that the LH surge might not have been induced in anovulated cows. Furthermore, E2 levels remained high in some anovulated cows compared to ovulated cows after PG treatment. Although the cause of this phenomenon is not known, it may be due to follicular E2 secretion problems. Cases where the DF did not ovulate occurred frequently in particular cows or when PG was administered on Day 6 or Day 7. Furthermore, when cows were injected with PG between Day 5 and Day 9, the response was worse than when the PG treatment was administered later in the cycle [52]. This suggested the existence of cows that cannot secrete E2 normally after PG treatment, or the existence of endocrine disturbance around the time when the dominance shifts from the 1st DF to the 2nd DF.

There are several methods that can be used to make TAI with PG a practical proposition. One way is to control the E2 concentration in the blood [15]. The potential and timing of ovulation by an existing DF after PG treatment depend on the E2 concentration in the blood. Therefore, if the E2 concentration in the blood can be controlled, TAI with PG effectiveness should improve. It is known that exogenous estrogens in cows can induce a preovulatory-like LH surge and ovulation [24]. The injection of estradiol benzoate (ODB) induces a peak concentration of serum estradiol, the magnitude of which is similar to natural estrus [33] and reproduces the LH surge [5, 9, 38, 41]. In this study, the anovulation rate was high, even though all ovulations occurred 4 days after PG treatment in Group D6. If a clear E2 peak could be created in anovulation cows, it might be possible to induce ovulation. The optimum timing of treatment with ODB is 20 to 24 hr after PG treatment when the CL is absent and endogenous P4 is less than 1 ng/ml [5, 38, 41]. Evans et al. reported that PG treatment on Day 10 to Day 13 and ODB administration 24 hr later shortens the time from PG treatment to peak E2 levels or the LH surge. Furthermore, all 2nd DFs ovulated 4 days after PG treatment [15].

Another practical way to improve TAI using PG is to administer PG to cows that have a CL in their ovaries [6], give artificial insemination (AI) 3 days after PG treatment, and then confirm ovulation on the day after AI. If the DFs have not ovulated, AI can be given again at this point. This method might cover the ovulation that occurs between 4–6 days after PG treatment, and in this study, ovulation occurred 4–6 days after PG treatment in 97.9% of ovulated cows. Otherwise, AI can be given 3 days after PG treatment. Then ovulation can be confirmed 2 days after AI. If the DFs have still not ovulated, AI can be given again at this point. This method might cover ovulations that occur between 4 to 7 days after AI.

In conclusion, the type of ovulatory follicle induced by PG treatment and the number of days from PG treatment to ovulation depend on the E2 secretion ability of the DF present at the time of PG treatment. When a DF can secrete enough E2 to induce the GnRH surge immediately after PG treatment, then that DF will ovulate 4 days after PG treatment. However, if the DF has already lost the ability to secrete E2, a new DF develops and ovulates 5 to 7 days after PG treatment. In addition, a possible cause of anovulation, despite regression of the CL after PG treatment, may be abnormal follicular E2 secretion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams G. P., Jaiswal R., Singh J., Malhi P.2008. Progress in understanding ovarian follicular dynamics in cattle. Theriogenology 69: 72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2007.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archbald L. F., Tran T., Massey R., Klapstein E.1992. Conception rates in dairy cows after timed-insemination and simultaneous treatment with gonadotrophin releasing hormone and/or prostaglandin F2 alpha. Theriogenology 37: 723–731. doi: 10.1016/0093-691X(92)90151-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball P. J. H., Jackson P. S.1984. The use of milk progesterone profiles for assessing the response to cloprostenol treatment of non-detected oestrus in dairy cattle. Br. Vet. J. 140: 543–549. doi: 10.1016/0007-1935(84)90005-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beal W. E.1998. Current estrus synchronization and artificial insemination programs for cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 76: 30–38. doi: 10.2527/1998.76suppl_330x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolt D. J., Scott V., Kiracofe G. H.1990. Plasma LH and FSH after estradiol, norgestomet and Gn-RH treatment in ovariectomized beef heifers. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 23: 263–271. doi: 10.1016/0378-4320(90)90040-M [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun N. S., Heath E., Chenault J. R., Shanks R. D., Hixon J. E.1988. Effects of prostaglandin F2 alpha on degranulation of bovine luteal cells on days 4 and 12 of the estrous cycle. Am. J. Vet. Res. 49: 516–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chebel R. C., Santos J. E. P., Cerri R. L. A., Rutigliano H. M., Bruno R. G. S.2006. Reproduction in dairy cows following progesterone insert presynchronization and resynchronization protocols. J. Dairy Sci. 89: 4205–4219. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72466-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colazo M. G., Mapletoft R. J.2014. A review of current timed-AI (TAI) programs for beef and dairy cattle. Can. Vet. J. 55: 772–780. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Convey E. M., Kesner J. S., Padmanabhan V., Carruthers T. D., Beck T. W.1981. Luteinizing hormone releasing hormone-induced release of luteinizing hormone from pituitary explants of cows killed before or after oestradiol treatment. J. Endocrinol. 88: 17–25. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0880017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cordoba M. C., Fricke P. M.2002. Initiation of the breeding season in a grazing-based dairy by synchronization of ovulation. J. Dairy Sci. 85: 1752–1763. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(02)74249-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crowe M. A., Williams E. J.2012. Triennial lactation symposium: effects of stress on postpartum reproduction in dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. 90: 1722–1727. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cutullic E., Delaby L., Gallard Y., Disenhaus C.2012. Towards a better understanding of the respective effects of milk yield and body condition dynamics on reproduction in Holstein dairy cows. Animal 6: 476–487. doi: 10.1017/S175173111100173X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutullic E., Delaby L., Causeur D., Michel G., Disenhaus C.2009. Hierarchy of factors affecting behavioural signs used for oestrus detection of Holstein and Normande dairy cows in a seasonal calving system. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 113: 22–37. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobson H., Smith R., Royal M., Knight C., Sheldon I.2007. The high-producing dairy cow and its reproductive performance. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 42 Suppl 2: 17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2007.00906.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans A. C. O., O’Keeffe P., Mihm M., Roche J. F., Macmillan K. L., Boland M. P.2003. Effect of oestradiol benzoate given after prostaglandin at two stages of follicle wave development on oestrus synchronisation, the LH surge and ovulation in heifers. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 76: 13–23. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4320(02)00238-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gümen A., Guenther J. N., Wiltbank M. C.2003. Follicular size and response to Ovsynch versus detection of estrus in anovular and ovular lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 86: 3184–3194. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73921-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ireland J. J., Roche J. F.1982. Development of antral follicles in cattle after prostaglandin-induced luteolysis: changes in serum hormones, steroids in follicular fluid, and gonadotropin receptors. Endocrinology 111: 2077–2086. doi: 10.1210/endo-111-6-2077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isobe N., Nakao T.2002. Direct enzyme immunoassay of estrone sulfate in the plasma of cattle. J. Reprod. Dev. 48: 75–78. doi: 10.1262/jrd.48.75 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isobe N., Nakao T.2003. Direct enzyme immunoassay of progesterone in bovine plasma. Anim. Sci. J. 74: 369–373. doi: 10.1046/j.1344-3941.2003.00128.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson P. S., Johnson C. T., Furr B. J., Beattie J. F.1979. Influence of stage of oestrous cycle on time of oestrus following cloprostenol treatment in the bovine. Theriogenology 12: 153–167. doi: 10.1016/0093-691X(79)90081-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaim M., Rosenberg M., Folman Y.1990. Management of reproduction in dairy heifers based on the synchronization of estrous cycles. Theriogenology 34: 537–547. doi: 10.1016/0093-691X(90)90010-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kastelic J. P., Knopf L., Ginther O. J.1990. Effect of day of prostaglandin F2α treatment on selection and development of the ovulatory follicle in heifers. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 23: 169–180. doi: 10.1016/0378-4320(90)90001-V [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerbrat S., Disenhaus C. A.2004. proposition for an updated behavioral characterization of the oestrus period in dairy cows. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 87: 223–238. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2003.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lammoglia M. A., Short R. E., Bellows S. E., Bellows R. A., MacNeil M. D., Hafs H. D.1998. Induced and synchronized estrus in cattle: dose titration of estradiol benzoate in peripubertal heifers and postpartum cows after treatment with an intravaginal progesterone-releasing insert and prostaglandin F2α. J. Anim. Sci. 76: 1662–1670. doi: 10.2527/1998.7661662x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lane E. A., Crowe M. A., Beltman M. E., More S. J.2013. The influence of cow and management factors on reproductive performance of Irish seasonal calving dairy cows. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 141: 34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2013.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larson L. L., Ball P. J. H.1992. Regulation of estrous cycles in dairy cattle: A review. Theriogenology 38: 255–267. doi: 10.1016/0093-691X(92)90234-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez H., Satter L. D., Wiltbank M. C.2004. Relationship between level of milk production and estrous behavior of lactating dairy cows. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 81: 209–223. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2003.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melendez P., Gonzalez G., Aguilar E., Loera O., Risco C., Archbald L. F.2006. Comparison of two estrus-synchronization protocols and timed artificial insemination in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 89: 4567–4572. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72506-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mihm M., Crowe M. A., Knight P. G., Austin E. J.2002. Follicle wave growth in cattle. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 37: 191–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0531.2002.00371.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore K., Thatcher W. W.2006. Major advances associated with reproduction in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 89: 1254–1266. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72194-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreira F., de la Sota R. L., Diaz T., Thatcher W. W.2000. Effect of day of the estrous cycle at the initiation of a timed artificial insemination protocol on reproductive responses in dairy heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 78: 1568–1576. doi: 10.2527/2000.7861568x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navanukraw C., Redmer D. A., Reynolds L. P., Kirsch J. D., Grazul-Bilska A. T., Fricke P. M.2004. A modified presynchronization protocol improves fertility to timed artificial insemination in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 87: 1551–1557. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73307-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Rourke M., Diskin M. G., Sreenan J. M., Roche J. F.2000. The effect of dose and route of oestradiol benzoate administration on plasma concentrations of oestradiol and FSH in long-term ovariectomised heifers. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 59: 1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4320(99)00094-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pursley J. R., Mee M. O., Wiltbank M. C.1995. Synchronization of ovulation in dairy cows using PGF2α and GnRH. Theriogenology 44: 915–923. doi: 10.1016/0093-691X(95)00279-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pursley J. R., Kosorok M. R., Wiltbank M. C.1997. Reproductive management of lactating dairy cows using synchronization of ovulation. J. Dairy Sci. 80: 301–306. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(97)75938-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rafsal K. R., Jarrin-Maldonado J. H., Nachreiner R. F.1987. Endocrine profiles in cows with ovarian cysts experimentally induced by treatment with exogenous estradiol or adrenocorticotropic hormone. Theriogenology 28: 871–889. doi: 10.1016/0093-691X(87)90038-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roelofs J., López-Gatius F., Hunter R. H. F., van Eerdenburg F. J. C. M., Hanzen C.2010. When is a cow in estrus? Clinical and practical aspects. Theriogenology 74: 327–344. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2010.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan D. P., Snijders S., Aarts A., O’Farrell K. J.1995. Effect of estradiol subsequent to induced luteolysis on development of the ovulatory follicle and interval to estrus and ovulation. Theriogenology 43: 310. doi: 10.1016/0093-691X(95)92464-K [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sartori R., Haughian J. M., Shaver R. D., Rosa G. J., Wiltbank M. C.2004. Comparison of ovarian function and circulating steroids in estrous cycles of Holstein heifers and lactating cows. J. Dairy Sci. 87: 905–920. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73235-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scaramuzzi R. J., Turnbull K. E., Nancarrow C. D.1980. Growth of Graafian follicles in cows following luteolysis induced by the prostaglandin F2 alpha analogue, cloprostenol. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 33: 63–69. doi: 10.1071/BI9800063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Short R. E., Randel R. D., Staigmiller R. B., Bellows R. A.1979. Factors affecting estrogen-induced LH release in the cow. Biol. Reprod. 21: 683–689. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod21.3.683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Souza A. H., Ayres H., Ferreira R. M., Wiltbank M. C.2008. A new presynchronization system (Double-Ovsynch) increases fertility at first postpartum timed AI in lactating dairy cows. Theriogenology 70: 208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2008.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stangaferro M. L., Wijma R. W., Giordano J. O.2019. Profitability of dairy cows submitted to the first service with the Presynch-Ovsynch or Double-Ovsynch protocol and different duration of the voluntary waiting period. J. Dairy Sci. 102: 4546–4562. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-15567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stangaferro M. L., Wijma R., Masello M., Thomas M. J., Giordano J. O.2018. Economic performance of lactating dairy cows submitted for first service timed artificial insemination after a voluntary waiting period of 60 or 88 days. J. Dairy Sci. 101: 7500–7516. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-14484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stevens R. D., Seguin B. E., Momont H. W.1995. Evaluation of the effects of route of administration of cloprostenol on synchronization of estrus in diestrous dairy cattle. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 207: 214–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stevenson J. S., Phatak A. P.2005. Inseminations at estrus induced by presynchronization before application of synchronized estrus and ovulation. J. Dairy Sci. 88: 399–405. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72700-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stevenson J. S., Lucy M. C., Call E. P.1987. Failure of timed insemination and associated luteal function in dairy cattle after two injections of prostaglandin F2- alpha. Theriogenology 28: 937–946. doi: 10.1016/0093-691X(87)90044-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stevens R. D., Momont H. W., Seguin B. E.1993. Simultaneous injection of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and the prostaglandin F2α analog cloprostenol (PGF) disrupts follicular activity in diestrous dairy cows. Theriogenology 39: 381–387. doi: 10.1016/0093-691X(93)90381-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stevenson J. S., Pursley J. R., Garverick H. A., Fricke P. M., Kesler D. J., Ottobre J. S., Wiltbank M. C.2006. Treatment of cycling and noncycling lactating dairy cows with progesterone during Ovsynch. J. Dairy Sci. 89: 2567–2578. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72333-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vasconcelos J. L., Silcox R. W., Rosa G. J., Pursley J. R., Wiltbank M. C.1999. Synchronization rate, size of the ovulatory follicle, and pregnancy rate after synchronization of ovulation beginning on different days of the estrous cycle in lactating dairy cows. Theriogenology 52: 1067–1078. doi: 10.1016/S0093-691X(99)00195-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walsh S. W., Williams E. J., Evans A. C. O.2011. A review of the causes of poor fertility in high milk producing dairy cows. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 123: 127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2010.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wiltbank M. C., Pursley J. R.2014. The cow as an induced ovulator: timed AI after synchronization of ovulation. Theriogenology 81: 170–185. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2013.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yániz J. L., Murugavel K., López-Gatius F.2004. Recent developments in oestrous synchronization of postpartum dairy cows with and without ovarian disorders. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 39: 86–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2004.00483.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]