Abstract

A large number of preclinical studies have established that general anesthetics (GAs) may cause neurodevelopmental toxicity in rodents and nonhuman primates, which is followed by long-term cognitive deficits. The subiculum, the main output structure of hippocampal formation, is one of the brain regions most sensitive to exposure to GAs at the peak of synaptogenesis (i.e., postnatal day (PND) 7). We have previously shown that subicular neurons exposed to GAs produce excessive amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which is a known modulator of neuronal excitability. To further explore the association between GA-mediated increase in ROS levels and long-term functional changes within subicular neurons, we sought to investigate the effects of ROS on excitability of these neurons using patch-clamp electrophysiology in acute rat brain slices. We hypothesized that both acute application of H2O2 and an early exposure (at PND 7) to GA consisting of midazolam (9 mg/kg), 70% nitrous oxide, and 0.75% isoflurane can affect excitability of subicular neurons and that superoxide dismutase and catalase mimetic, EUK-134, may reverse GA-mediated hyperexcitability in the subiculum. Our results using whole-cell recordings demonstrate that acute application of H2O2 has bidirectional effects on neuronal excitability: lower concentrations (0.001%, 0.3 mM) cause an excitatory effect, whereas higher concentrations (0.01%, 3 mM) inhibited neuronal firing. Furthermore, 0.3 mM H2O2 increased the average action potential frequency of subicular neurons by almost twofold, as assessed using cell-attach configuration. Finally, we found that preemptive in vivo administration of EUK-134 reduced GA-induced long-lasting hyperexcitability of subicular neurons ex vivo when studied in neonatal and juvenile rats. This finding suggests that the increase in ROS after GA exposure may play an important role in regulating neuronal excitability, thus making it an attractive therapeutic target for GA-induced neurotoxicity in neonates.

Keywords: Free oxygen radicals, Lasting hyperexcitability, Rat subicular neurons

Introduction

The prevailing preclinical literature proves that commonly used general anesthetics (GAs) cause widespread neurodegeneration in the developing mammalian brain, especially in the thalamus and hippocampus [1, 2]. This is important since GA-induced neurodegeneration in the hippocampus during brain development appears to have a lasting role in impairing memory and cognitive processing later in life [1, 3]. The hippocampus is located within both medial temporal lobes of the brain and is primarily devoted to memory formation and storage [4]. The hippocampus may be anatomically divided into three regions: the dentate gyrus (DG), Ammon’s Horn or Cornu Ammonis fields 1–3 (CA1–3), and the subiculum. The subiculum is highly intertwined with the hippocampal CA1 region, anterior thalamic nuclei, entorhinal cortex (EC), and cingulate cortices, and serves as the main input from CA1 to cerebral cortex [5, 6]. Importantly, our previous studies have shown that the subiculum is exquisitely sensitive to GA-induced neurotoxic insults as evidenced by very prominent developmental apoptosis [1, 7]. Not only that we and others have been reporting histo-morphological damage caused by early exposure to clinically used GAs, but we have also documented that reticular thalamic neurons (nRT) remain chronically hyperexcitable following exposure to GAs at PND 7 [8]. However, the possible role of GAs in modifying the function of ion channels that control neuronal excitability in the subiculum during brain development has not been examined.

It has been suggested that excitability of hippocampal neurons may be regulated by the various products of oxidative metabolism [9]. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), the superoxide anion (O2−), and the hydroxyl radical (OH−) are generated as byproducts of oxidative metabolism in neurons and, importantly, could be produced when the neurons are exposed to certain inhaled GAs, such as nitrous oxide [10]. Most studies regarding early exposure to GA have sought to characterize ultrastructural changes at the level of the synapse [11], the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within the hippocampus [12], and peroxidative species that promote neuronal cell death [13]. Specifically, our group has shown that ROS levels in the hippocampus of rat pups are upregulated after the exposure to GAs during the crucial period of brain development, i.e., at PND 7 [13]. Furthermore, we found that GAs may modulate mitochondrial complexes responsible for maintaining normal physiological ROS levels [12]. In an effort to further understand how exposure to GAs-mediated increases in ROS levels may lead to long-term functional changes within subicular neurons, we sought to investigate the effects of ROS upon the function of these neurons using an acute slice preparation ex vivo. Our hypothesis was that acute application of H2O2, as well as exposure to GA, may have a direct effect on excitability of subicular neurons, and that superoxide dismutase and catalase mimetic, EUK-134, may reverse or diminish GA-mediated hyperexcitability in the subiculum.

We report that acute applications of H2O2 cause concentration-dependent opposing effects on neuronal excitability. Moreover, we found that the in vivo administration of EUK-134 prior to GAs exposure (at PND 7), an approach previously shown to ameliorate GA-induced neurodegeneration [13], attenuated GA-mediated long-lasting hyperexcitability of subicular neurons ex vivo when studied in neonatal and juvenile rats.

Material and Methods

Drugs

Stock solutions of H2O2 (Sigma Aldrich, 50% wt.% in H2O) were prepared daily using sterile water, and then freshly diluted to the final concentrations in the external solution at the time of electrophysiology experiments. EUK-134 (Carman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Michigan) was dissolved in 0.1% DMSO.

Animals

Neonatal and juvenile (PND 7–27) Sprague-Dawley rats (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN, USA) of both sexes were used in this study. Animals were housed within accredited animal facilities according to protocols approved by the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee. Treatments of rats adhered to guidelines set forth in the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and number of animals necessary to produce reliable scientific data.

Brain Slice Preparation for Patch-Clamp Experiments

Animals were anesthetized briefly with isoflurane and decapitated, and their brains rapidly removed. Horizontal or sagittal brain slices (250–300 μm) were sectioned at 4 °C in a prechilled solution containing (in mM): sucrose 260, d-glucose 10, NaHCO3 26, NaH2PO4 1.25, KCl 3, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2, using a tissue slicer (Leica VT 1200S). Brain slices were immediately incubated for 45 min at 37 °C in solution containing (in mM): NaCl 124, d-glucose 10, NaHCO3 26, NaH2PO4 1.25, KCl 4, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2 prior to use in electrophysiology experiments, which were done at room temperature. During incubation, slices were constantly per-fused with a gas mixture of 95 vol% O2 and 5 vol% CO2. Subicular neurons throughout the pyramidal and polymorphic layers between CA1 and presubiculum were selected randomly for electrophysiological recordings.

Electrophysiology Experiments

The external solution for all whole-cell electrophysiology experiments of neuronal excitability consisted of (in mM) NaCl 125, d-glucose 25, NaHCO3 25, NaH2PO4 1.25, KCl 2.5, MgCl2 1, and CaCl2 2. This solution was equilibrated with a mixture of 95 vol% O2 and 5 vol% CO2 for at least 30 min with a resulting pH of about 7.4. The internal solution for all current-clamp recordings and cell-attach experiment with the acute application of H2O2 consisted of (in mM) potassium-d-gluconate 130, EGTA 5, NaCl 4, CaCl2 0.5, HEPES 10, Mg ATP 2, Tris-GTP 0.5, and pH 7.3. The internal solution for cell-attach experiment in animals after exposure to general anesthesia consisted of (in mM) NaCl 150, glucose 10, HEPES 10, CaCl2 2.5, MgCl2 1.3, and KCl 5, whereas the external solution was NaCl 125, glucose 10, NaH2PO4 1.25, NaHCO3 26, KCl 5, MgCl 0.25, and CaCl2 0.25. For recording of evoked inhibitory post-synaptic currents (eIPSCs), we used an internal solution containing, in mM, 130 KCl, 4 NaCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 MgATP2, 0.5 Tris-GTP, and 5 lidocaine N-ethyl bromide. pH was adjusted with KOH to 7.25. For recordings of evoked excitatory post-synaptic currents (eEPSCs), this solution was modified by replacing KCl with equimolar K-gluconate. To eliminate glutamatergic excitatory currents, all recordings of eIPSCs were done in the presence of 5 μM NBQX (2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione) and 50 μM d-APV ((2R)-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid; AP5, (2R)-amino-5 phosphonopentanoate) in a bath solution. To eliminate inhibitory currents, all recordings of eEPSCs were done in the presence of 20 μM picrotoxin (a non-competitive GABAA antagonist) in bath solution.

Glass micropipettes (Sutter Instruments O.D. 1.5 mm) were pulled using a Sutter Instruments model P-1000 and fabricated to maintain an initial resistance of 3–5 MΩ. Neuronal membrane responses were recorded using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Foster City, CA). Voltage-current commands and digitization of the resulting voltages and currents were performed with Clampex 8.3 software (Molecular Devices, Foster City, CA) running on a compatible computer. Resulting current and voltage traces were analyzed using Clampfit 10.5.

Intrinsic excitability of subicular neurons after the perfusion with H2O2 was characterized by injecting a family of depolarizing (5–190 pA) current pulses of 500-ms duration in 10-pA incremental steps through the recording pipette. We also used a multi-step protocol which consisted of injecting a family of depolarizing (50–200 pA) current pulses of 400-ms duration followed by a series of hyperpolarizing currents in 50-pA increments stepping from − 200 to − 300 pA. All recordings were made in the presence of GABAA and ionotropic glutamate receptor blockers ((20 μM picrotoxin, 50 μM d-2-amino-5-phosphonovalerate (D-APV) and 5 μM 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione (NBQX)) in the external solution. Subsequent resting membrane potentials, tonic action potential frequencies, and input resistances were determined. Resting membrane potential was measured at the beginning of each recording and was not corrected for the liquid junction potential, which was around 10 mV in our experiments. The membrane input resistance was calculated by dividing the end of steady-state hyperpolarizing voltage deflection by the injected current.

To further elucidate lasting effects of H2O2, general anesthesia, and EUK-134 on neuronal excitability while minimally affecting the intrinsic properties, subicular neurons were subjected to a single-unit extracellular (loose) or cell-attach protocol at the holding membrane potential of 0 mV [14]. Spontaneous action potentials were recorded using this patch-clamp configuration and later analyzed offline with MiniAnalysis (Synaptosoft, Inc., Decatur, GA).

To examine acute effects of H2O2 on synaptic currents, we stimulated pyramidal subiculum neurons with a Constant Current Isolated Stimulator DS3 (Digitimer, Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire, England). Electrical field stimulation was achieved by placing a stimulating electrode within the hippocampal CA1 soma layer with simulation intervals of at least 20 s to allow recovery of synaptic responses. In all recordings, we first determined the current-output relationship, then used current intensities in the stimulating electrode corresponding to the maximal amplitudes of eIPSCs and eEPSCs. Recordings were made with the standard whole-cell voltage-clamp technique. Neurons were typically held at − 70 mV.

Anesthesia Delivery

At postnatal day (PND) 7, Sprague-Dawley rat pups of both sexes were randomly assigned to one of four treatment protocols, each 6 h in duration: (1) sham controls (21% O2+ vehicle, 0.1% DMSO); (2) general anesthesia (GA: midazolam, 9 mg/kg, i.p.; single injection given immediately before the administration of 0.75% isoflurane + 75% N2O + about 24% O2); (3) GA+EUK-134 (EUK-134 at 10 mg/kg, s.c.; total of two doses were administered—first, 24 h and second dose 30 min prior to GA); (4) EUK-134 alone (same dosing regimen). An agent-specific vaporizer was used to deliver a set percentage of isoflurane with a mixture of O2 and N2O gases. The temperature-controlled chambers were preset to maintain the ambient temperature at 33–34 °C. The composition of gases was analyzed using real-time feedback (Datex Capnomac Ultima) to assess the levels of isoflurane, N2O, CO2, and O2. Rat pups were separated from their mothers during the exposure and were reunited immediately thereafter.

Typically, control (sham) animals were littermates exposed to 6 h of mock anesthesia consisting of separation from their mother in an air-filled chamber and i.p. injections of 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), vehicle used to dissolve midazolam. For control (sham) animals, 0.1% DMSO was used to substitute midazolam. The experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, and by the Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA. All experiments were done in accordance with the Public Health Service’s Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used. Only PND 7 rat pups underwent different treatment protocols as outlined above. Electrophysiological recordings from the PND 7-treated rats were obtained later at the age ranging PND 14–27. The data obtained from animals of both sexes were combined for the subsequent analysis.

Data Analysis

In all electrophysiology experiments, we attempted to obtain as many neurons as possible from each animal in order to minimize the number of animals used. Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed paired t test or two-way ANOVA; the continuous data sets were analyzed using repeated measures design. Significance was accepted as p < 0.05. In the case of significant interaction, Sidak’s or Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons was also used, depending on the data set analyzed, as recommended by GraphPad Prism 7.02 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Issues of normality and heterogeneity of variation were evaluated to determine the adequacy of the ANOVA models and whether additional manipulations were warranted. Statistical and graphical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7.02 software and Origin 2018 (OriginLab, Northhampton, MA). Results are presented as means ± SEM.

Results

The Effects of Hydrogen Peroxide on Intrinsic Excitability of Subicular Neurons

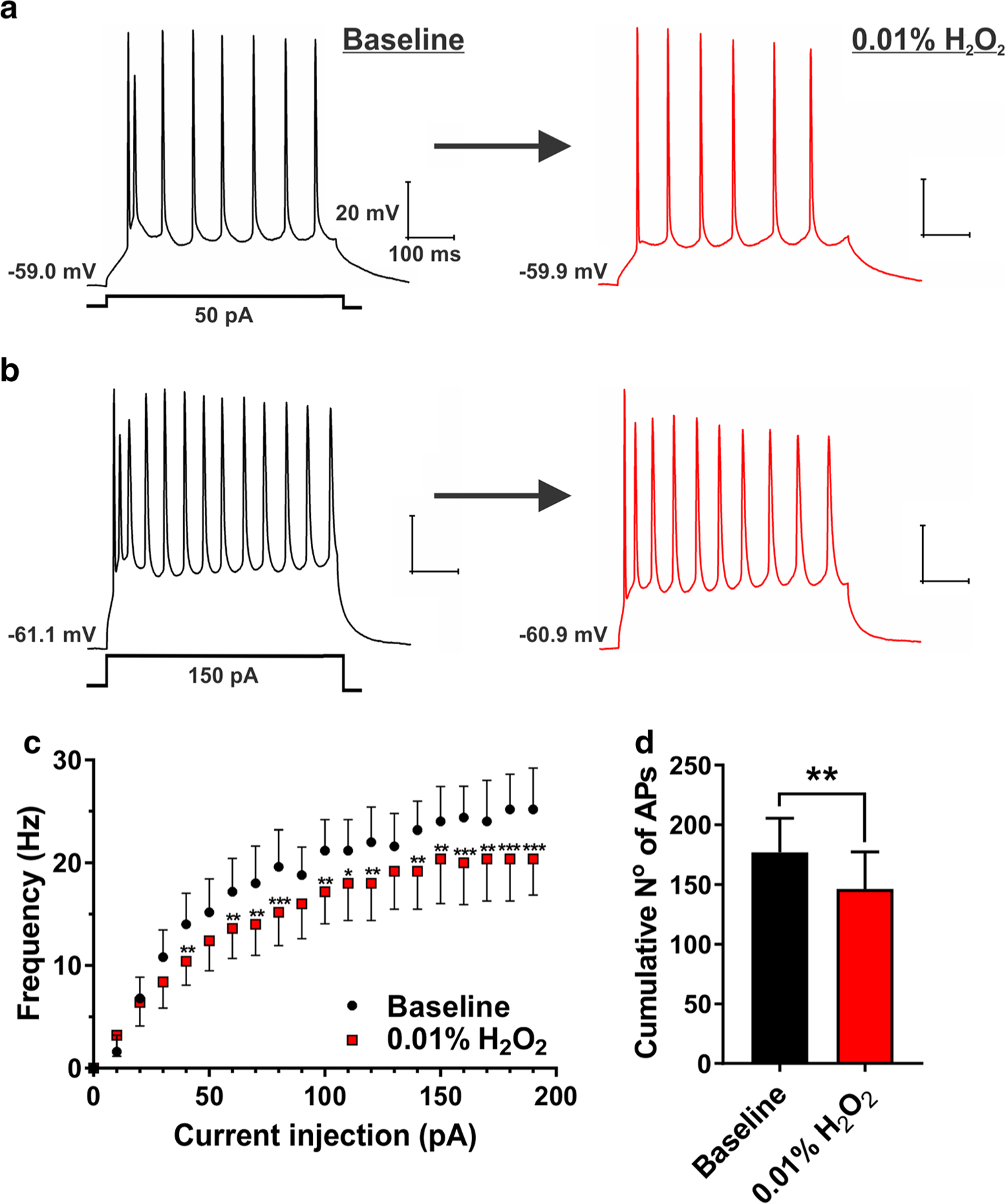

Previous studies showed that low millimolar concentrations of H2O2 may decrease excitability of ventral horn neurons [15] and CA1 hippocampal neurons [16], both from neonatal rats. Hence, we first explored the effects of 3 mM (0.01%) H2O2 on intrinsic neuronal excitability in the rat subiculum. Original traces depicted in Fig. 1 (panels a and b) show that this concentration of H2O2 decreased evoked action potential (AP) frequency in a representative subicular neuron. This effect was evident across a series of depolarizing current injections, ranging from 20 to 30% inhibition after the application of H2O2 (Fig. 1c), which consequently resulted in a significant decrease in the cumulative number of APs, as compared with the baseline (Fig. 1d). Importantly, the resting membrane potential was significantly hyperpolarized (baseline, − 60.3 ± 1.7 mV vs. H2O2, − 66.4 ± 2.1 mV, P = 0.001), whereas input resistance was significantly increased after 0.01% H2O2 (baseline, − 130.1 ± 5.7 MΩ vs. H2O2, − 166.6 ± 7.0 MΩ, P < 0.001). For more accurate comparisons to the baseline conditions, we held the membrane potential slightly depolarized after the application of H2O2 (− 62.2 ± 0.9 mV).

Fig. 1.

H2O2 (0.01%) decreased evoked neuronal excitability in the subiculum. a and b Original traces from a representative subicular neuron depicting active membrane responses to a 50- and 150-pA depolarizing stimulus in the absence (black trace) and presence of 0.01% H2O2 (red trace). c A family of escalating current injections revealed the lower firing frequency of subicular neurons after the application of 0.01% H2O2 (two-way RM ANOVA, interaction F19,76 = 3.22, P < 0.001; Sidak’s post hoc test *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 vs. baseline). d Bar graph shows a significant decrease in the cumulative number of action potentials (AP) after the application of 0.01% H2O2 (paired t test t4 = 7.94, **P = 0.001; n = 5 neurons, two PND 15–16 rats)

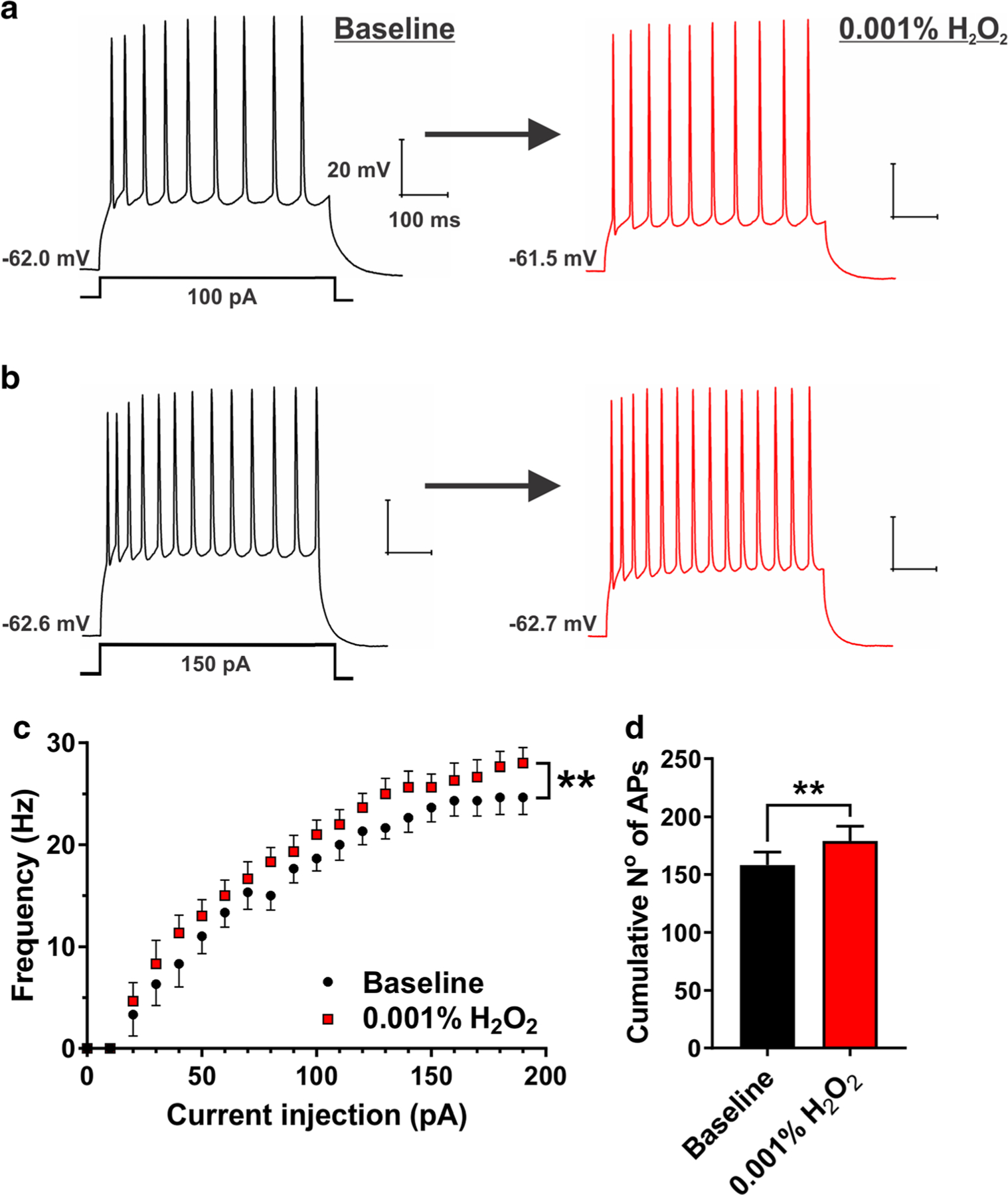

Next, we tested the effects of 0.3 mM H2O2 (0.001%) upon evoked neuronal excitability, which may be more relevant concentration in the context of accumulation of ROS after brain injury [17]. We found that this concentration caused an opposite effect on subicular excitability, as shown by the original traces in Fig. 2, panels a and b. Namely, 0.001% H2O2 induced relatively small (10 to 30%), but consistent increase in evoked AP firing frequency of subicular neurons (Fig. 2c), which was also evidenced by the cumulative number of APs (Fig. 2d). In this experiment, the resting membrane potential was not significantly affected by H2O2 (baseline, − 59.2 ± 1.4 mV vs. H2O2, − 60.4 ± 1.7 mV, P = 0.165); nonetheless, the membrane potential was held at a value almost identical to the baseline conditions (− 59.5 ± 1.2 mV). Interestingly, and similarly to our previous experiment with 0.01% H2O2 (as outlined earlier), we detected an increase in input resistance of subicular neurons (baseline, − 147.4 ± 17.2 MΩ vs. H2O2, − 170.2 ± 21.8 MΩ, P = 0.029). Taken together, our data on passive membrane properties (e.g., input resistance) after 0.01% or 0.001% H2O2 could not alone explain H2O2’s effects on neuronal excitability. Our results suggest that H2O2, depending on its concentration in the brain tissue, may bidirectionally modulate intrinsic neuronal excitability in the rat subiculum.

Fig. 2.

H2O2 (0.001%) increased evoked neuronal excitability in the subiculum. a and b Original traces from a representative subicular neuron depicting active membrane responses to a 100- and 150-pA depolarizing stimulus in the absence (black trace) and presence of 0.001% H2O2 (red trace). c A family of escalating current injections revealed an increase in AP firing frequency of subicular neurons after the application of 0.001% H2O2 (two-way RM ANOVA, interaction F19,95 = 1.65, P = 0.059; factor treatment F1,5 = 37.80, **P = 0.002; factor current injection F19,95 = 94.05, P < 0.001. d Bar graph shows a significant increase in the cumulative number of APs after the application of 0.001% H2O2 (paired t test t5 = 6.15, **P = 0.002; n = 6 neurons, four PND 16–23 rats)

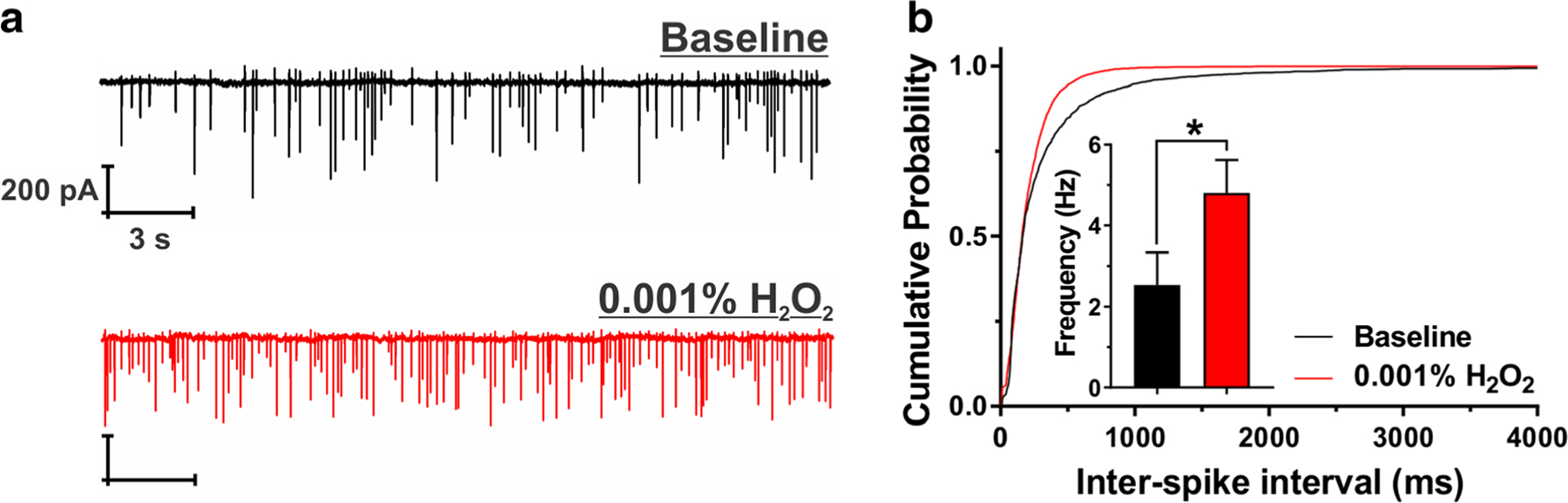

The Effects of Hydrogen Peroxide on Spontaneous AP Firing Frequency of Subicular Neurons

Cell-attach configuration allows recording of the electrical activity of neurons without influencing the properties of the cell membrane or the intracellular milieu [14]. Hence, to further explore our results on H2O2-induced hyperexcitability, we took advantage of this patch-clamp configuration and recorded spontaneous APs after acute application of 0.001% H2O2. Representative original traces obtained at baseline conditions (black) and after 0.001% H2O2 (red) are shown in Fig. 3a. Similar to the results on evoked neuronal excitability, our cell-attach recordings after 0.001% H2O2 revealed hyperexcitability as evident by a significant decrease in inter-spike intervals presented in cumulative probability plots in Fig. 3b. Consequently, we detected an almost twofold increase in the average AP frequency (baseline, 2.54 ± 0.79 Hz; H2O2, 4.81 ± 0.82 Hz, P < 0.05; inset of Fig. 3b). Thus, we confirmed that low concentrations of H2O2 may cause hyperexcitability of subicular neurons when recording both evoked and spontaneous AP firing properties, as assessed by whole-cell and cell-attach approaches, respectively.

Fig. 3.

H2O2 (0.001%) increased spontaneous AP frequency of subicular neurons. a Original traces from a representative subicular neuron depicting cell-attach recordings of APs in the absence (black trace) and presence of 0.001% H2O2 (red trace). b Cumulative probability plots for baseline (black; 2680 spikes) and H2O2 (red; 6646 spikes) demonstrate shorter inter-spike intervals after the application of 0.001% H2O2. This finding is confirmed by the higher average AP frequency presented in the inset (paired t test t5 = 3.06, *P = 0.028; n = 6 neurons, three PND 16–23 rats)

In the present study, we also investigated the effects of acutely applied H2O2 at a concentration of 0.001% (0.3 mM) on evoked inhibitory post-synaptic currents (eIPSC) and evoked excitatory (eEPSC) in the rat subiculum. We found that both eIPSCs and eEPSCs were not significantly affected by this concentration of H2O2 (− 12.7 ± 14.7%, P = 0.450 and 4.8 ± 10.9%, P = 0.650, compared with baseline, respectively; data not shown).

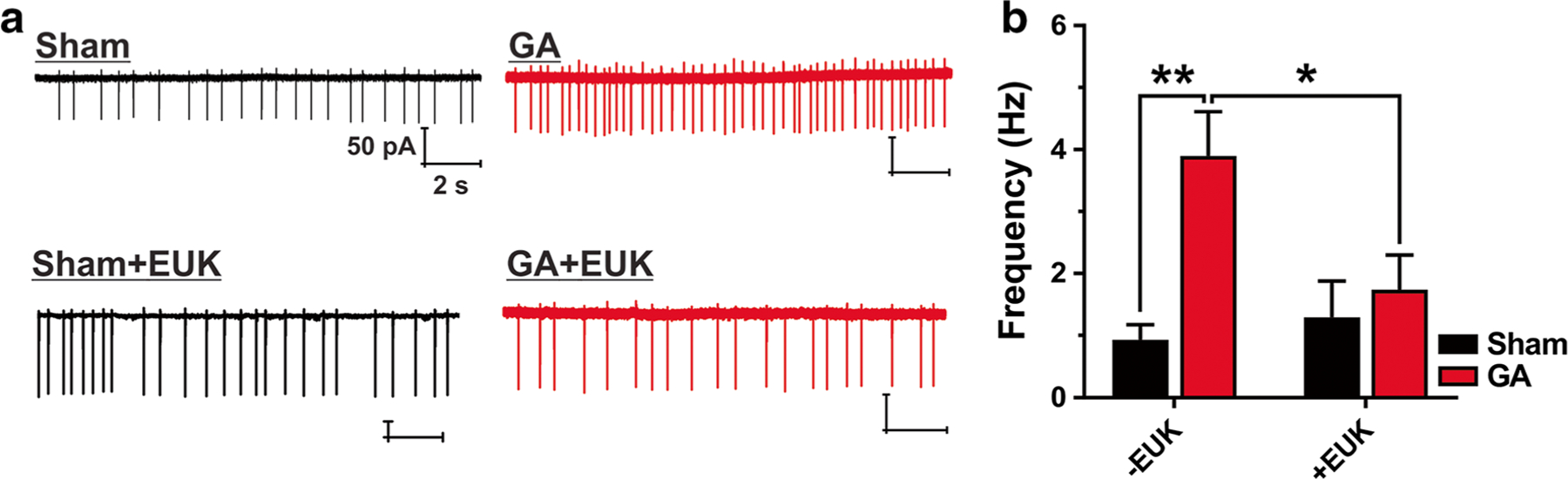

The Effects of GA Exposure at PND 7 on Long-Term Excitability of Subicular Neurons

Our group showed that early exposure to GAs may cause lasting change in excitability of neurons within nucleus reticularis thalami (nRT), which in turn causes hyperexcitability of thalamocortical circuitry [8]. To investigate whether GAs exposure at PND 7 may also cause lasting changes in the excitability of rat hippocampal formation, subicular neurons were subjected to a single-unit extracellular (loose) or cell-attach patch-clamp protocol at the age of PND 14–27. Indeed, we observed a profound increase in spontaneous AP firing frequency in the GA-treated group of about 4-fold (3.9 ± 1.0 Hz), when compared with the sham (0.9 ± 0.2 Hz) controls (Fig. 4). When we treated PND 7 animals with EUK-134 at the time of GA exposure, we observed almost complete reversal in AP firing frequency. Namely, the co-administration of EUK-134 reduced the hyperexcitability when compared with GA-exposed animals (GAs, 3.9 ± 1.0 Hz; GA+EUK, 1.7 ± 0.6 Hz, and sham+EUK, 1.3 ± 0.6 Hz). We conclude that ROS may have an important role in mediating lasting hyperexcitability of subicular neurons after exposure to GAs during brain development.

Fig. 4.

Pretreatment with EUK-134 rescues subicular pyramidal neurons from GA-mediated increased spontaneous AP firing frequency. a Original traces from representative subicular neurons depicting cell-attach recordings from sham-, general anesthesia- (GA), Sham+EUK-134- and GA+EUK-134-treated rats. b Subicular neurons in the GA group showed significantly higher AP frequency than the ones in the sham group (two-way RM ANOVA, interaction F1,37 = 4.91, P = 0.019; Tukey’s post hoc test **P = 0.002 vs. sham). This effect was rescued when EUK-134, a synthetic reactive oxygen species scavenger, was co-injected with GA (*P = 0.042 vs. GA and P = 0.926 vs. sham+EUK). There was very little difference in AP firing frequency between the sham group and sham+EUK group (P = 0.95). Sham, n = 13 neurons, six rats; GA, n = 8 neurons, three rats; sham+EUK, n = 11 neurons, three rats; GA+EUK, n = 10 neurons, three rats. All data were obtained in recordings from PND 14–27 rats

Discussion

Modern pediatric medicine relies on safe and dependable general anesthesia. Over 4 million children are being anesthetized annually in the USA alone. We believed until about two decades ago that this practice was innocuous and without long-term sequelae. Unfortunately, rapidly emerging animal and clinical evidence suggests that early exposure to anesthesia disturbs normal brain development leading to permanent cognitive and behavioral impairments, not only in rodents and monkeys but possibly in humans as well. This led to a recently issued FDA warning that “Health care professionals should balance the benefits of appropriate anesthesia in young children and pregnant women against the potential risks” [18].

The recent focus has been on understanding the pertinent mechanisms of anesthesia-induced developmental neurotoxicity so that protective strategies can be devised. Although focus of many studies in this field has been on understanding the mechanisms leading to GA-induced neuroapoptosis [12], very little is known about the function of the neurons that survive neuroapoptotic insult. Our data strongly suggest that GA exposure during brain development promotes hyperexcitability in pyramidal subicular neurons shown as a lasting increase in the frequency of AP firing when recorded from acute brain slices up to 3 weeks post-GA exposure. It solidified our previous findings suggesting that the GA-induced excessive ROS production in the subiculum of PND 7 rat pups known to result in increased lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial membrane injury [13] may at least in part be responsible for long-lasting modulation of the firing patterns in subicular pyramidal neurons. Further confirmation that GA-induced excessive ROS production may be the cause of observed neuronal hyperexcitability comes from the fact that in vivo co-administration of GAs with EUK-134 also provides a complete reversal of GA-induced chronic hyperexcitable state in subicular neurons. Towards this end, we have previously shown that EUK-314 significantly downregulates GA-induced lipid peroxidation, preserves mitochondrial integrity, and completely prevents GA-induced cognitive impairment in young adult rats (PND 45–73) [13]. We conclude that ROS overproduction may be responsible for many deleterious effects of GAs on the developing hippocampal circuitry and suggests that agents like EUK-314 may be protective adjuvants.

The primary goal of our study was to investigate possible role of ROS in the alteration of neuronal excitability following GAs exposure during brain development. To our knowledge, actual concentrations of H2O2 in the brain tissue of rat pups during administration of GAs are not known. However, it is interesting to comment on our findings that acute applications of H2O2 induce opposing effects on subicular excitability with lower concentrations (0.3 mM) having an excitatory effect, and higher concentrations (3 mM) having an inhibitory effect. Bidirectional responses to acute applications of similar concentrations of H2O2 in acute slice preparations were reported in other brain regions, such as brainstem or CA1 hippocampal area [16]. For example, acute application of H2O2 at 0.5 mM concentration induced initial reduction in spike firing, followed by lasting hyperexcitability in nucleus tractus solitarii (nTS) neurons that persisted even after the washout of H2O2 [19]. Interestingly, in the same study, authors found that the excitatory synaptic currents in nTS were insensitive to acute applications of H2O2, similar to our findings in the subiculum. In another study conducted in ex vivo guinea pig brain slices, authors have shown that 1.5 mM H2O2 can inhibit activity of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta by targeting ATP-sensitive potassium channels, while increasing the activity of GABAergic neurons in the dorsal striatum and substantia nigra pars reticulata via non-selective TRPM2 (transient receptor potential melastatin 2) cation channel [9]. Finally, it was reported that H2O2, at 2.2 mM, evoked transient depression followed by increased neuronal activity in the ventral respiratory column of brain stem of neonatal mice, while in the same preparation, H2O2 inhibited the activity of only hippocampal CA1 neurons [16]. This strongly suggests that H2O2 is an important signaling molecule; however, its effects on neuronal excitability may be region- and neuronal circuitry-dependent. Precise molecular mechanisms of biphasic effects of H2O2 on neuronal excitability and a variety of ion channels located in the subiculum remain an important area of future investigations.

In humans, MRI studies have shown that the subiculum is implicated in learning and memory [20]. In rodents, the consensus is that the subiculum-specific lesions produce impairments in the learning of visual-spatial tasks; however, these impairments are not as severe as compared with those resulting from an injury in CA1 [21]. It is noteworthy that GAs-mediated alterations in hippocampal neuronal structure and function are not subiculum selective and that the modulations in spatial learning acquisition are most likely due to the sum of the alterations changes within CA1 and other hippocampal regions as well [1, 2]. Towards this end, post-mortem studies of the subiculum pyramidal neurons from subjects with schizophrenia have detected smaller pyramidal cell bodies and structurally altered dendrites [22]. The subiculum also has an important role in the initiation and maintenance of epileptic discharges in temporal lobe epilepsy [23]. Furthermore, it is well documented that hippocampal neuron hyperexcitability may underlie certain cognitive impairments in both animals and humans [24, 25]. We hypothesized that the hyperexcitability of subicular neurons may initially be a homeostatic adaptive compensatory mechanism in response to apoptotic neuronal loss induced by GAs. However, this eventually may become a maladaptive process and induces lasting plasticity of subicular neurons that may in turn contribute to cognitive deficits seen in rodents after exposure to GAs.

In conclusion, drugs that are catalase and superoxide dismutase mimetics, such as EUK-134, may in part lower anesthetic-induced free radical production, thereby blunting the toxic effects GA exposure while preserving the normal course of neuronal circuitries formation. Our findings regarding the function of subicular pyramidal neurons suggest that GA exposure also leads to the hyperexcitability and that the administration of EUK-134 prior to GAs administration may spare subicular neuron function. However, careful interpretation and classification of the free radical signaling pathways involved must be taken into consideration in order to avoid unwanted effects caused by co-administered drug, for the introduction of a drug that lowers free radical concentration may inadvertently alter brain development as well. Further preclinical studies are needed to address this issue.

Funding Information

This study was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. R01GM102525 to S.M.T. and Grant No. R01GM118197 to V.J-T.).

Footnotes

The experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, and by the Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA. All experiments were done in accordance with the Public Health Service’s Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Hartman RE, Izumi Y, et al. (2003) Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. 23:876–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yon J-H, Daniel-Johnson J, Carter LB, Jevtovic-Todorovic V (2005) Anesthesia induces neuronal cell death in the developing rat brain via the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways. Neuroscience 135:815–827. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.03.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loepke AW, Istaphanous GK, McAuliffe JJ et al. (2009) The effects of neonatal isoflurane exposure in mice on brain cell viability, adult behavior, learning, and memory. Anesth Analg 108:90–104. 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818cdb29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Squire LR, Zola-Morgan S (1991) The medial temporal lobe memory system. Science 253:1380–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witter MP, Ostendorf RH, Groenewegen HJ (1990) Heterogeneity in the dorsal subiculum of the rat. Distinct neuronal zones project to different cortical and subcortical targets. Eur J Neurosci 2:718–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witter M (2006) Connections of the subiculum of the rat: topography in relation to columnar and laminar organization. Behav Brain Res 174:251–264. 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atluri N, Joksimovic SM, Oklopcic A, Milanovic D, Klawitter J, Eggan P, Krishnan K, Covey DF et al. (2018) A neurosteroid analogue with T-type calcium channel blocking properties is an effective hypnotic, but is not harmful to neonatal rat brain. Br J Anaesth 120:768–778. 10.1016/j.bja.2017.12.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiGruccio MR, Joksimovic S, Joksovic PM et al. (2015) Hyperexcitability of rat thalamocortical networks after exposure to general anesthesia during brain development. J Neurosci 35: 1481–1492. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4883-13.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee CR, Patel JC, O’Neill B, Rice ME (2015) Inhibitory and excitatory neuromodulation by hydrogen peroxide: translating energetics to information. J Physiol 593:3431–3446. 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.273839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orestes P, Bojadzic D, Lee J, Leach E, Salajegheh R, DiGruccio MR, Nelson MT, Todorovic SM (2011) Free radical signalling underlies inhibition of CaV3.2 T-type calcium channels by nitrous oxide in the pain pathway. J Physiol 589:135–148. 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.196220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lunardi N, Ori C, Erisir A, Jevtovic-Todorovic V (2010) General anesthesia causes long-lasting disturbances in the ultrastructural properties of developing synapses in young rats. Neurotox Res 17:179–188. 10.1007/s12640-009-9088-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez V, Feinstein SD, Lunardi N, Joksovic PM, Boscolo A, Todorovic SM, Jevtovic-Todorovic V (2011) General anesthesia causes long-term impairment of mitochondrial morphogenesis and synaptic transmission in developing rat brain. Anesthesiology 115: 992–1002. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182303a63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boscolo A, Starr J, Sanchez et al. (2012) The abolishment of anesthesia-induced cognitive impairment by timely protection of mitochondria in the developing rat brain: the importance of free oxygen radicals and mitochondrial integrity. Neurobiol Dis 45: 1031 10.1016/J.NBD.2011.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nunemaker CS, DeFazio RA, Moenter SM (2003) A targeted extracellular approach for recording long-term firing patterns of excitable cells: a practical guide. Biol Proced Online 5:53–62. 10.1251/bpo46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohashi M, Hirano T, Watanabe K, Shoji H, Ohashi N, Baba H, Endo N, Kohno T (2016) Hydrogen peroxide modulates neuronal excitability and membrane properties in ventral horn neurons of the rat spinal cord. Neuroscience 331:206–220. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia AJ, Khan SA, Kumar GK et al. (2011) Hydrogen peroxide differentially affects activity in the pre-Bötzinger complex and hippocampus. J Neurophysiol 106:3045–3055. 10.1152/jn.00550.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyslop PA, Zhang Z, Pearson DV, Phebus LA (1995) Measurement of striatal H202 by microdialysis following global forebrain ischemia and reperfusion in the rat: correlation with the cytotoxic potential of H202 in vitro [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.FDA Drug Safety Communication. FDA review results in new warnings about using general anesthetics and sedation drugs in young children and pregnant women. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-review-results-new-warnings-about-using-general-anesthetics-and. Accessed 15 May 2019

- 19.Ostrowski TD, Hasser EM, Heesch CM, Kline DD (2014) H2O2 induces delayed hyperexcitability in nucleus tractus solitarii neurons. Neuroscience 262:53–69. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabrielli JDE, Brewer JB, Desmond JE, Glover GH (1997) Separate neural bases of two fundamental memory processes in the human medial temporal lobe. Science (80- ) 276:264–266. 10.1126/science.276.5310.264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris RGM, Schenk F, Tweedie F, Jarrard LE (1990) Ibotenate lesions of hippocampus and/or subiculum: dissociating components of allocentric spatial learning. Eur J Neurosci 2:1016–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosoklija G, Toomayan G, Ellis SP, Keilp J, Mann JJ, Latov N, Hays AP, Dwork AJ (2000) Structural abnormalities of subicular dendrites in subjects with schizophrenia and mood disorders: preliminary findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57:349–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stafstrom CE (2005) The role of the subiculum in epilepsy and epileptogenesis. Epilepsy Curr 5:121–129. 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2005.00049.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palop JJ, Mucke L (2009) Epilepsy and cognitive impairments in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 66:435 10.1001/archneurol.2009.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noebels J (2011) A perfect storm: converging paths of epilepsy and Alzheimer’s dementia intersect in the hippocampal formation. Epilepsia 52:39–46. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02909.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]