A novel and highly contagious severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 causes Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) which is currently pandemic worldwide (1). Over 1 million cases have been diagnosed in the beginning of April, 2020 (2). COVID-19 patients and asymptomatic carriers are the sources of infection (3). Although common clinical presentations are fever and respiratory symptoms, about 26% have gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms according to a study of 254 COVID-19 cases from Wuhan (4). Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 RNA has also been found in patients' fecal samples (4). Potential aerosol and fecal-oral transmission arouse much concern among endoscopists because endoscopies are considered aerosol-generating procedures. Unfortunately, nosocomial infection has occurred in some hospitals. According to an analysis of 138 hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, 41% patients were highly suspicious of nosocomial infection (5). Up to February 11, there are 1,716 hospital staff who had been infected with COVID-19, accounting for 3.8% of national cases. Among them, 6 died. The aforementioned situations have made GI endoscopy “high-risk” procedures during this pandemic. To reduce the risk of nosocomial transmission, some hospitals in China have suspended all endoscopic procedures. However, this causes delay in treating life-threatening situations. Therefore, how to carry out necessary endoscopic procedures with both endoscopy staff and patients well protected is a question of high priority at the present.

During this pandemic, our center continued with necessary endoscopic procedures. Herein, we summarized our indications, work flow, precautions, and endoscopic reprocessing and staff protection during COVID-19 pandemic based on our institutional experience of 109 cases with reference to recent Chinese and international guidelines (6–11).

INDICATIONS FOR NECESSARY ENDOSCOPIC PROCEDURES DURING COVID-19 PANDEMIC

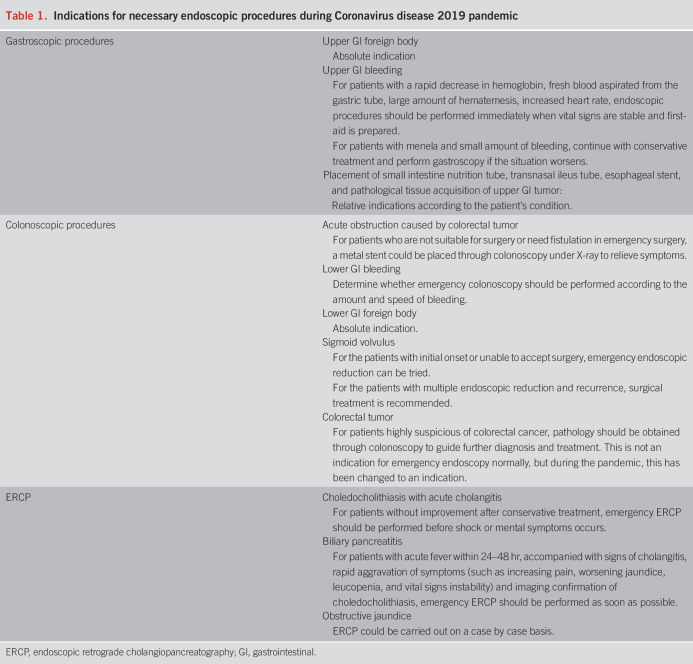

Please refer to Table 1 for indications of necessary endoscopy. Necessary endoscopy refers to situations when endoscopic procedures will alter life-threatening conditions or will change clinical management in 4–6 weeks. Elective endoscopy should be rescheduled.

Table 1.

Indications for necessary endoscopic procedures during Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic

SUMMARIZATION OF 109 ENDOSCOPIC CASES DURING COVID-19 PANDEMIC

We have performed 109 GI endoscopic procedures from January 23, 2020, to March 4, 2020. Among them, there were 59 gastroscopies (45 foreign body removal, 15 upper GI bleeding, 1 transnasal ileus tube placement, and 3 small intestine nutrition tube placement), 24 colonoscopies (15 lower GI bleeding, 8 lower GI stent placement, and 1 sigmoid volvulus reduction), and 26 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (18 choledocholithiasis with acute cholangitis, 3 biliary pancreatitis, 1 bleeding, and 4 obstructive jaundice). For upper GI bleeding, common reasons were esophageal variceal hemorrhage and peptic ulcer, whereas for lower GI bleeding, common reasons were diverticular bleeding and tumor. In most cases (104/109), endoscopy yielded a diagnosis. All endoscopic interventions were successful without complications. There was no suspected or confirmed case of COVID-19 among these patients, and no nosocomial infection occurred.

WORK FLOW, PRECAUTIONS, REPROCESSING, AND STAFF PROTECTION DURING COVID-19 PANDEMIC

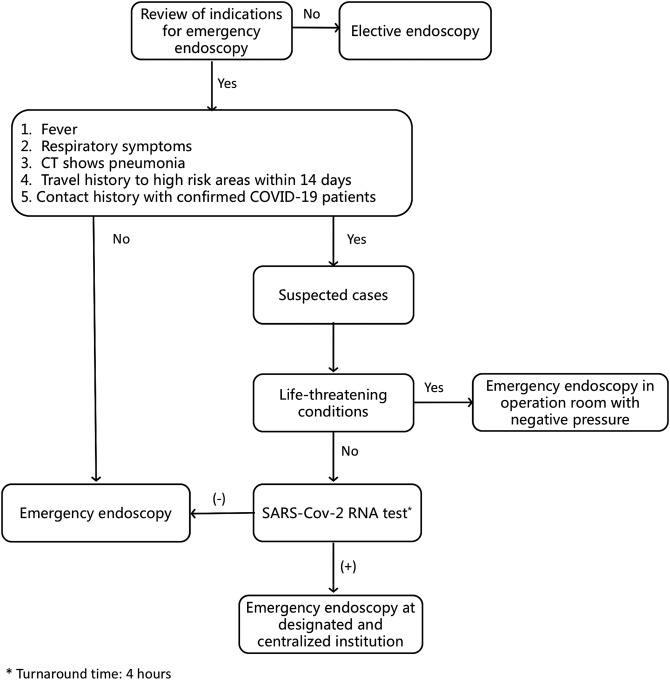

Figure 1 shows our work flow. Careful review of indications is crucial to save life-threatening conditions without unnecessary increased nosocomial infection risk. It is also necessary to differentiate COVID-19 fever from fever induced by underlying GI conditions, such as cholangitis, inflammation, and perforation secondary to embedded foreign bodies.

Figure 1.

Work flow of endoscopic procedures during COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; CT, computed tomography; SARS-Cov-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

At reception, the patients and their companions should be reconfirmed with potential COVID-19 symptoms and contact history. An epidemiological survey should be filled out with complete contact information for potential contact tracing in case nosocomial infection develops. In preprocedure and postprocedure areas, staffs are equipped with surgical masks, cap, and gowns. Patients are seated separately (at least 1 m distance from each other) and given surgical masks to be worn at all times.

Single-use bed sheets and endoscopic devices are used. Only 1 doctor and 1 nurse were allowed in the procedure room. When contacting afebrile and patients unsuspected with COVID-19, medical staff should wear a surgical mask or N95 mask (according to local availability), cap, disposable water-proof gown, gloves, shoe covers, and goggles/face shield. During ERCP, enteral stenting, or contacting febrile patients, isolation screens could be used to provide further protection against splashing (Figure 2). Procedures for suspected COVID-19 cases should be performed in endoscopy rooms with negative pressure. In institutions without necessary criteria, avoid performing endoscopy in suspected patients and transfer patients to other institutions, except for inevitable situations. Procedures for confirmed COVID-19 cases should be performed in designated institutions with centralized treatment of COVID-19. During this pandemic, we avoid unnecessary anesthesia to decrease exposure of anesthesiologists. If intravenous anesthesia is needed, the anesthesiologists should wear proper personal protective equipment with goggles or face shield. If intubation is needed, anesthesiologists should wear N95 masks, and only the anesthesiologist stays in the room during intubation, whereas the rest of the team remains outside until intubation is finished. In institutions performing physician-based sedated endoscopy, physicians should be protected accordingly.

Figure 2.

An isolation screen for protection against splashing.

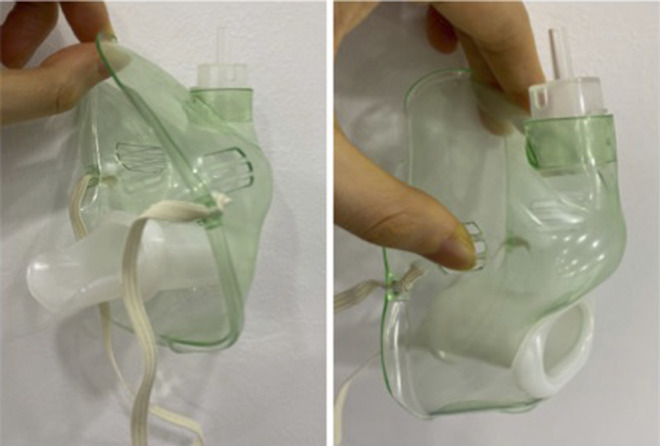

Patients should also be well protected. For patients receiving colonoscopy, surgical masks should be worn at all times. During anesthesia, oxygen mask should be put outside the surgical mask. For patients receiving gastroscopy or ERCP, a special disposable device combing the bite block and oxygen mask (Figure 3) is provided to prevent respiratory droplets from spreading.

Figure 3.

A special disposable device combing the bite block and oxygen mask for gastroscopy.

During the procedure, verbal communication should be minimized. Caution should be taken to avoid the biopsy channel facing the operator's face. During this pandemic, endoscopic treatment aims to solve the critical and life-threatening conditions and to minimize cross-infection to the largest extent. For example, when ERCP is performed for choledocholithiasis with acute cholangitis, only biliary drainage with plastic stent or nasobiliary tube should be recommended instead of aiming for complete stone removal.

After the procedure, all surfaces (beds, trolleys, floors, counters, etc.) contacted with patients or staff shall be wiped with chlorine (500 mg/L) containing disinfectant, and ultraviolet disinfection shall last for at least 30 minutes in the operation room. Mobile air sterilization station shall be used for 15–25 minutes.

After standard bedside cleaning, the contaminated endoscope is put into a biohazardous medical waste bag and sent to the reprocessing room by an airtight transfer trolly. The cleaning tank should be equipped with antiaerosol isolation screen device. High-level sterilization is routinely performed. Different from performing leakage test before washing, during the pandemic, leakage test should be performed after washing. Although potential leakage may cause severe damage to the scopes, this change minimizes staffs' contact with body fluid.

In conclusion, although GI endoscopy is a “high-risk” procedure during COVID-19 pandemic, it is irrational to stop all endoscopic procedures. Instead, for a careful trade-off between potential risk of nosocomial infection and saving life-threatening conditions, selection of indications for necessary endoscopy cannot be overemphasized. During the pandemic, strict epidemiological survey and differential diagnosis of fever is crucial. With appropriate protection, necessary endoscopic procedures are safe and effective. A clear work flow will be helpful for the performance of safe and effective endoscopy.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Pinghong Zhou, MD, PhD, FASGE.

Specific author contributions: Xinyang Liu, MD, MPH, Mingyan Cai, MD, PhD, and Qiang Shi, MD, PhD, share co-first authorship. Study concept and design: P.W. and P.Z. Acquisition of data: X.L. and Q.S. Drafting of the manuscript: X.L. and Q.S. Critical revision of the manuscript: M.C. and P.Z. Study supervision: P.Z.

Financial support: None to report.

Potential competing interests: None to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, et al. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020;395(10223):470–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/685d0ace521648f8a5beeeee1b9125cd). Acessed April 3, 2020.

- 3.Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature 2020. 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang H, Kang Z, Gong H, et al. The digestive system is a potential route of 2019-nCov infection: A bioinformatics analysis based on single-cell transcriptomes. BioRxiv 2020, In Press. doi: 10.1101/2020.01.30.927806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020;323(11):1061–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-02/19/content_5480948.htm). Acessed February 18, 2020.

- 7.(http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-02/05/content_5474791.htm). Acessed February 2, 2020.

- 8.(http://www.csde.org.cn/news/detail.aspx?article_id=2883). Acessed February 4, 2020.

- 9.Lui R, Wong S, Sánchez‐Luna S, et al. Overview of guidance for endoscopy during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, in press. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiu PWY, Ng SC, Inoue H, et al. Practice of endoscopy during COVID-19 pandemic: Position statements of the Asian Pacific Society for Digestive Endoscopy (APSDE-COVID statements). Gut 2020, epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Repici A, Maselli R, Colombo M, et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: What the Department of Endoscopy should know. Gastrointest Endosc 2020, epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]