INTRODUCTION

Abdominal pain and hypertransaminasemia are gastrointestinal symptoms reported in approximately 10% and in more than 20% of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, respectively (1,2). SARS-CoV-2 infection has also been associated with a prothrombotic profile accounting for a high risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (3,4). We present a case of acute portal vein thrombosis (PVT) in a SARS-CoV-2-positive patient.

CASE REPORT

A 72-year-old man with Parkinson disease, anxious-depressive syndrome, and mild vascular dementia was referred to our emergency department with fever, jaundice, and obnubilation. Table 1 shows the blood analyses and the main cardiorespiratory parameters at presentation. Chest x-ray excluded pulmonary consolidations, and ultrasound exploration was negative for cholelithiasis and dilatation of the biliary tract. He was diagnosed for Escherichia coli sepsis associated with hypotension, hypertransaminasemia, nonobstructive jaundice, and acute kidney injury. Antibiotic therapy, fluid challenge, and low flow oxygen therapy (2 L/min) allowed reaching prompt clinical amelioration except for fever. On day 2, he resulted positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Hence, he was admitted to our COVID-19 unit and enoxaparin at 4000 IU o.d. was added to the therapy.

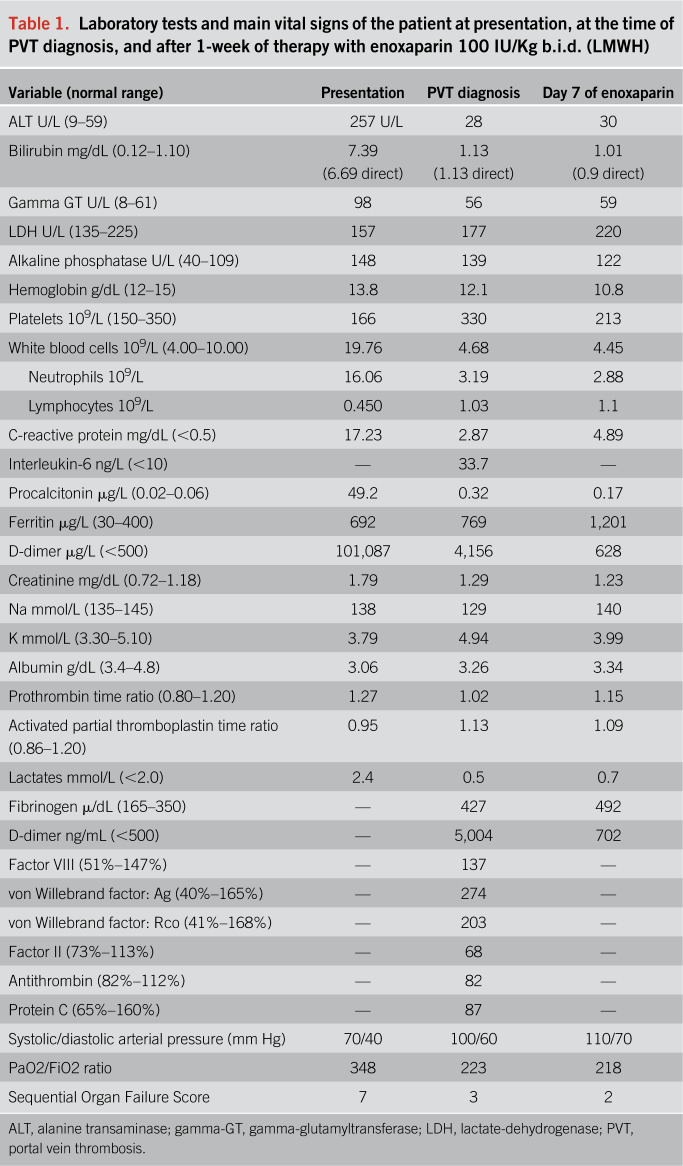

Table 1.

Laboratory tests and main vital signs of the patient at presentation, at the time of PVT diagnosis, and after 1-week of therapy with enoxaparin 100 IU/Kg b.i.d. (LMWH)

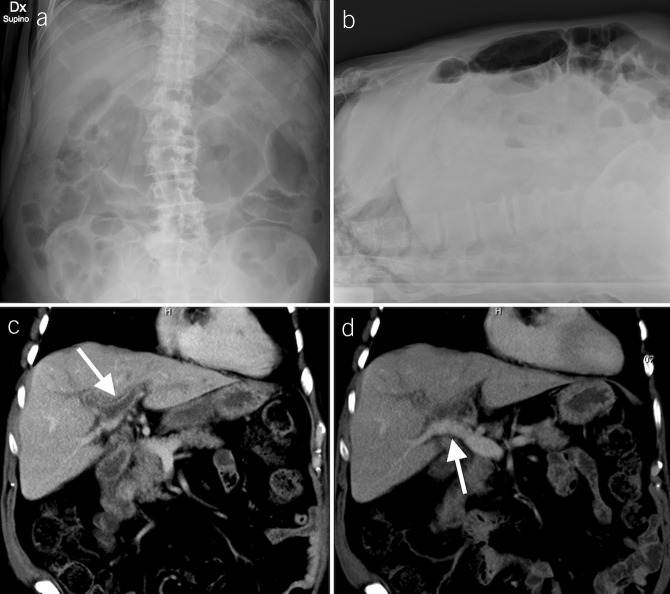

On day 6, mild abdominal pain with bloating and constipation complicated the clinical course. The patient presented with periumbilical tenderness with no rebound reaction nor ascites. Abdominal x-ray showed signs of adynamic ileus (Figure 1, panel A–B). An abdominal computed tomography scan revealed PVT described as the total occlusion of the left portal venous system and the secondary branches of the right portal vein (Figure 1, panel C–D). Contrast enhancement of the wall was an expression of thrombophlebitis. A large area of transient hepatic attenuation differences in the liver segments supplied by thrombosed branches was also detected.

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior (A) and laterolateral (B) abdominal x-rays show gas distension of the small bowel with some air-fluid levels (B) and signs of paralytic ileus (A and B). Coronal reformatted CT images show thrombosis of the left portal vein and the right portal vein with its branches for VIII and V segments (C, arrow). The right posterior portal vein, the main portal vein, the splenic vein, and the superior mesenteric vein were patent, without CT signs of portal hypertension (D, arrow). CT, computed tomography.

For the acute presentation of thrombosis, the dose of enoxaparin was increased to 100 IU/Kg b.i.d. Active causes of chronic liver disease were excluded (e.g., alcohol, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus infection). The imaging ruled out advanced signs of cirrhosis. The temporary hypertransaminasemia and hyperbilirubinemia detected at presentation were likely a manifestation of an acute ischemic hepatitis because both arterial and venous hepatic blood flow were impaired due to sepsis-related hypotension and PVT. Inherited and acquired thrombophilia was also excluded, considering the systemic inflammation as the main risk factor for thrombosis.

Pain relief was rapidly achieved, and bloating abdomen resolved 48 hours after anticoagulation. The Sequential Organ Failure Score from presentation, which had already lowered from 7 to 3 at the time of PVT detection, was 2 after 7 days of full dose of enoxaparin. Among coagulation tests, von Willebrand factor, D-dimer, and fibrinogen were abnormal, as described in patients with COVID-19 (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Our observation is consistent with previous reports of high thrombotic risk in COVID-19. We emphasize, however, that although screening for pulmonary embolisms and deep vein thrombosis has been recommended in this clinical setting, little attention has been paid for venous thrombosis at the splanchnic venous system.

Detecting PVT in patients with COVID-19 with acute abdominal pain would have important therapeutic and prognostic implications because a prompt anticoagulation would reduce the risk of early complications such as intestinal infarction and would contrast the chronic evolution toward portal cavernoma (5).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Flora Peyvandi, MD, PhD.

Specific author contributions: All authors equally contributed to the manuscript.

Financial support: This work was in part granted by the Bando Ricerca Corrente (Italian Minister of Health).

Potential competing interests: None to report.

Informed consent: Informed patient consent was obtained for this case report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cheung KS, Hung IF, Chan PP, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection and virus load in fecal samples from the Hong Kong cohort and systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2020. (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.065) [Epub ahead of print April 3, 2020.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang C, Shi L, Wang FS. Liver injury in COVID-19: Management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5(5):428–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost 2020;18(4):844–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llitjos JF, Leclerc M, Chochois C, et al. High incidence of venous thromboembolic events in anticoagulated severe COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Haemost 2020. (doi: 10.1111/jth.14869) [Epub ahead of print April 22, 2020.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonetto DA, Singal AK, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. ACG clinical guideline: Disorders of the hepatic and mesenteric circulation. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115(1):18–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]