Highlights

-

•

What is the primary question addressed by this study? As a medical student interest group, can we alleviate social isolation suffered by nursing home residents during the COVID-19 pandemic through weekly phone calls?

-

•

What is the main finding of this study? The Yale Geriatrics Student Interest Group implemented the Telephone Outreach in the COVID-19 Outbreak Program at three nursing homes with initial success. Nursing home residents report looking forward to their weekly phone calls and gratitude for social connectedness.

-

•

What is the meaning of this finding? Social isolation and loneliness in nursing home seniors—a common concern now exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic—is partly relieved by our replicable telephone outreach program.

KEY WORDS: Social Isolation, loneliness, elderly, COVID-19

Abstract

Objective

Social isolation and loneliness—common concerns in older adults—are exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. To address social isolation in nursing home residents, the Yale School of Medicine Geriatrics Student Interest Group initiated a Telephone Outreach in the COVID-19 Outbreak (TOCO) Program that implements weekly phone calls with student volunteers.

Methods

Local nursing homes were contacted; recreation directors identified appropriate and interested elderly residents. Student volunteers were paired with elderly residents and provided phone call instructions.

Results

Three nursing homes opted to participate in the program. Thirty elderly residents were paired with student volunteers. Initial reports from recreation directors and student volunteers were positive: elderly residents look forward to weekly phone calls and express gratitude for social connectedness.

Conclusions

The TOCO program achieved initial success and promotes the social wellbeing of nursing home residents. We hope to continue this program beyond the COVID-19 pandemic in order to address this persistent need in a notably vulnerable patient population.

OBJECTIVE

Social isolation and loneliness are common concerns in older adults. While social isolation is often conceptualized as the objective state of minimal social contact and integration, loneliness is the negative feeling accompanying perceived social isolation.1 Studies estimate that a range of 33%–72% older adults report feelings of loneliness and that a larger proportion of these individuals live in a residential home.2, 3, 4, 5 Loneliness is associated with negative health outcomes, including increased morbidity and mortality.6 Moreover, there are significant mental health consequences of loneliness, including cognitive decline3 , 7 and symptoms of depression and anxiety.8 , 9 To date, activities offered in nursing home settings to address social isolation (e.g., games, outings) appear to have limited benefit.10 Although controversial and in its infancy, some data suggests the utility of socially assistive robotics to address social isolation in nursing home settings where the availability of healthcare providers may be less than optimal.11

As a result of restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the social isolation experienced by older adults has intensified.12 In nursing homes, residents are secluded in their rooms and no longer partake in communal meals or activities. They have extremely limited contact with support staff and are no longer able to receive visits from family members and friends. This exaggerated isolation—in addition to the threat of infection and the loss of contact with loved ones—is likely to contribute to feelings of loneliness and subsequent negative outcomes in the elderly.

In order to address concerns related to social isolation in nursing home residents, the Yale School of Medicine Geriatrics Student Interest Group created and implemented a Telephone Outreach in the COVID-19 Outbreak (TOCO) Program. This service aims to alleviate the social isolation suffered by older adults through weekly friendly phone calls with student volunteers.

METHODS

In order to promote the TOCO Program and to identify nursing home residents appropriate for phone contact, it was first necessary to establish partnerships with local nursing homes. Given the current heightened clinical responsibilities of healthcare workers in these facilities, initial outreach to facilities and their nursing staff was unsuccessful. Subsequently, nursing home recreation directors were contacted. Recreation directors identified eligible seniors interested in participation. In general, older individuals were approached if they were English-speaking and able to participate meaningfully in a telephone program.

Student volunteers were recruited through the Geriatrics Student Interest Group and through a volunteer forum publicized by the Yale School of Medicine Office of Student Affairs. If volunteers were available for regular weekly phone calls, they were paired with a nursing home resident.

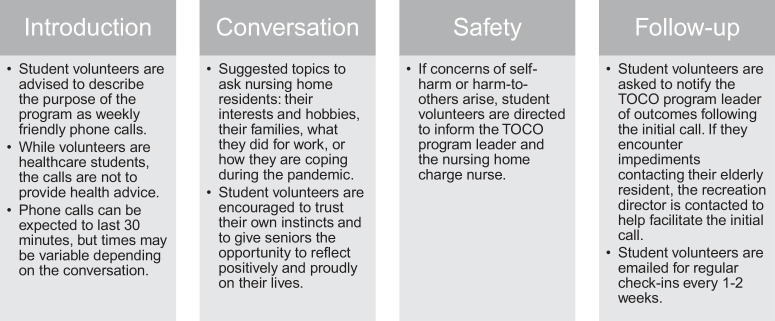

Volunteers were provided with general instructions and expectations for their phone calls (Fig. 1 ). They were given first names and landline telephone numbers for their senior companion. For the majority of residents, only landline telephone numbers were available given the technological limitations in this population (e.g., a lack of cell phones and hearing impairments). The duration of phone calls—while flexible—was expected to last approximately 30 minutes. While unlikely to occur given the friendly nature of the phone calls, students were instructed to break confidentiality with the charge nurse if concerns of self-harm or harm-to-others arose. Finally, volunteers were encouraged to set a regular schedule in order to foster predictability for their nursing home residents.

FIGURE 1.

The template of instructions and expectations communicated to student volunteers once assigned a nursing home resident.

RESULTS

To date, ten nursing homes in New Haven and the surrounding communities were contacted. The TOCO Program was implemented in three nursing homes. Thirty nursing home residents expressed interest in participating and were subsequently paired with student volunteers for weekly phone calls.

Initial reports from nursing home recreation directors and student volunteers were positive. In general, recreation directors convey their seniors deeply appreciated the program and benefited from meaningful conversations with their volunteer companions. Phone calls are generally interactive, in which both the nursing home residents and student volunteers share stories of their lives and their families. In addition, several volunteers identified unique and actionable needs of their senior companions. For example, one volunteer contacted the recreation director to obtain books for a resident.

Volunteers recognized common challenges experienced by many of these older adults, including feelings of restlessness and anxiety as isolation continues, and fearfulness as COVID-19 enters nursing home facilities. In addition, many nursing home residents experienced social isolation before the COVID-19 pandemic. These challenges are exacerbated by a lack of technology (e.g., limited computer and internet access to communicate with loved ones), as well as visual and hearing impairments. These factors similarly complicated phone calls with student volunteers: For example, hearing impairments and invalid landline telephone numbers impeded completion of initial phone calls. However, facilitation by recreation directors helped resolve these technical issues, allowing volunteers to effectively connect with the nursing home residents.

Finally, this program has positively—though inadvertently—impacted our student volunteers. Multiple volunteers voiced they have personally benefited from their weekly conversations with their nursing home companions. Not only have they reported a greater sense of purpose, but student volunteers also emphasize the impact older adults have on their own wellbeing, particularly their own feelings of social connectedness.

CONCLUSIONS

This novel program aims to alleviate exacerbated social isolation experienced by nursing home residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the feedback from nursing home administration and student volunteers, the TOCO Program has achieved initial success. Participating seniors look forward to their weekly phone calls and feel gratitude for new companionship during this period of loneliness. Furthermore, while the program intended to focus on the needs of nursing home residents, weekly friendly phone calls have benefited the social wellbeing of student volunteers as well.

The TOCO Program revealed the current social isolation experienced by nursing home residents existed prior to COVID-19 outbreak. Loneliness is an ongoing concern in older adults. In light of this realization, we hope to continue this program beyond the COVID-19 pandemic in order to address this persistent need in a notably vulnerable, and often neglected patient population.

Given the widespread and growing demand for social connectedness during the COVID-19 pandemic, our TOCO Program has significant potential for replication. Therefore, we recognize the importance of emphasizing the challenges met by the program. First, when establishing partnerships with nursing homes, it was evident their front-line healthcare workers were overwhelmed by COVID-19 and unable to participate in the identification of residents appropriate for the program. However, our program overcame this barrier by connecting with motivated recreation administrators. Their typical responsibility, the provision of communal activity support, is currently unavailable. Therefore, they are able to shift efforts to assist in the identification of appropriate residents.

The initial success of the program is encouraging. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, we plan to expand the TOCO Program to include more nursing home residents. Furthermore, given the ongoing social isolation expected after the outbreak, we hope to continue the program as a permanent Geriatrics Student Interest Group volunteer opportunity. Finally, in the near future, we aim to collect qualitative data from student volunteers to determine the personal and professional impact of the TOCO program, to assess their ability to sustain the regularity of weekly phone calls, and to identify ongoing actionable needs students can advocate for on behalf of nursing home residents. We also plan to host a ``debriefing” webinar with our faculty leadership and the TOCO student participants to encourage feedback and provide a discussion forum for the provision of ongoing supportive phone engagement.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Laura van Dyck and Drs. Kirsten Wilkins, Jennifer Ouellet, Gregory Ouellet, and Michelle Conroy made substantive intellectual contributions to the published study.

DISCLOSURE

A special thank you to Terry Duda and Greta Perrin of the Willows in Woodbridge, CT, Anna Becker of Evergreen Woods in North Branford, CT, and Stephanie Zilinski of Whitney Center in Hamden, CT. Without their hard work and dedication, this program would not have been possible.

The authors report no conflicts with any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Wenger GC, Davies R, Shahtahmasebi S. Social isolation and loneliness in old age: review and model refinement. Ageing Soc. 1996;16:333–358. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holmén K, Ericsson K, Winblad B. Social and emotional loneliness among non-demented and demented elderly people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2000;31:177–192. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(00)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tilvis R, Pitkälä K, Jolkkonen J. Feelings of loneliness and 10-year cognitive decline in the aged population. Lancet. 2000;356:77–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savikko N, Routasalo P, Tilvis RS. Predictors and subjective causes of loneliness in an aged population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2005;41:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prieto-Flores ME, Forjaz MJ, Fernandez-Mayoralas G. Factors associated with loneliness of noninstitutionalized and institutionalized older adults. J Aging Health. 2011;23:177–194. doi: 10.1177/0898264310382658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40:218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE. Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:234–240. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drageset J, Espehaug B, Kirkevold M. The impact of depression and sense of coherence on emotional and social loneliness among nursing home residents without cognitive impairment–a questionnaire survey. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:965–974. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santini ZI, Jose PE, Cornwell EY. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e62–e70. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Theurer K, Mortenson WB, Stone R. The need for a social revolution in residential care. J Aging Stud. 2015;35:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bemelmans R, Gelderblom GJ, Jonker P. Socially assistive robots in elderly care: a systematic review into effects and effectiveness. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.David E: The unspoken COVID-19 toll on the elderly: Loneliness [ABC news website]. April 14, 2020. Available at: https://abcnews.go.com/Health/unspoken-covid-19-toll-elderly-loneliness/story?id=69958717. Accessed April 20, 2020