Abstract

Background

Survivors of childhood brain tumors or other acquired brain injury (ABI) are at risk of poor health-related quality of life (HRQoL); its valid and reliable assessment is essential to evaluate the effect of their illness on their lives. The aim of this review was to critically appraise psychometric properties of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) of HRQoL for these children, to be able to make informed decisions about the most suitable PROM for use in clinical practice.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO for studies evaluating measurement properties of HRQoL PROMs in children treated for brain tumors or other ABI. Methodological quality of relevant studies was evaluated using the consensus-based standards for the selection of health status measurement instruments checklist.

Results

Eight papers reported measurement properties of 4 questionnaires: Health Utilities Index (HUI), PedsQL Core and Brain Tumor Modules, and Child and Family Follow-up Survey (CFFS). Only the CFFS had evidence of content and structural validity. It also demonstrated good internal consistency, whereas both PedsQL modules had conflicting evidence regarding this. Conflicting evidence regarding test-retest reliability was reported for the HUI and PedsQL Core Module only. Evidence of measurement error/precision was favorable for HUI and CFFS and absent for both PedsQL modules. All 4 PROMs had some evidence of construct validity/hypothesis testing but no evidence of responsiveness to change.

Conclusions

Valid and reliable assessment is essential to evaluate impact of ABI on young lives. However, measurement properties of PROMs evaluating HRQoL appropriate for this population require further evaluation, specifically construct validity, internal consistency, and responsiveness to change.

Keywords: acquired brain injury, brain tumor, children, patient-reported outcomes, systematic review

One child in every 600 will develop some form of cancer by age 16 years,1 and approximately 20% to 27% of these children will have a brain tumor.2 Currently, 65.4% of children diagnosed with a brain tumor in Europe from 1999 to 2007 are reported to survive 5 or more years from diagnosis3 and the majority should have prolonged survival and become adults. They often have multiple impairments and reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL).4–8 Approximately 62% will be left with a life-altering long-term disability9 comparable to the life-changing sequelae of severe traumatic or other acquired childhood brain injuries (ABI). ABI is postnatal injury to the brain that is sudden in onset and may be the result of head trauma, or nontraumatic following meningitis, stroke, metabolic derangement, sickle cell disease, or a brain tumor.

In children younger than 16 years, the incidence of hospitalization for traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been reported to be between 280 and 500 per 100 000. This implies that the total number of children admitted to the hospital for TBI per annum in the United Kingdom is at least 35 000. Of these, about 2000 (5.7%) will have severe TBI, 3000 (8.6%) moderate TBI, and 30 000 (85.7%) mild TBI. In addition, the total number of children who sustain nontraumatic coma associated with severe or moderate encephalopathy is approximately 4000 per year.10 Also, the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States reported the incidence rate of newly diagnosed cases of brain tumor in children to be 5.54 per 100 000, equating to 4500 new cases annually,11 and the overall annual incidence of childhood stroke has been estimated to be around 1.2 to 13 cases per 100 000 children younger than 18 years.12

In the context of delivery of clinical care, doctors vary in their ability to explore, elicit, and respond to information about HRQoL,13 and discussion of the emotional, social, and cognitive issues affecting HRQoL after ABI or childhood cancer does not routinely take place in clinic consultations.14 In addition, children and parents are often reluctant to raise psychosocial issues at clinic appointments,15,16 which they perceive to be more focused on medical issues such as monitoring tumor status and its response to antitumor treatments or complications of other types of ABI.

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) evaluate a patient’s health status or HRQoL at a single point in time and are collected through short, self-completed questionnaires17 without any third party acting as an intermediary. In the context of clinical research, the use of PROMs, including those assessing HRQoL, has proved to be a practicable means of assessing quality of survival in multicenter treatment trials.18,19 Individualized use of PROMs in the routine care of children with a long-term illness has the potential to add valuable information about the impact of the disease, inform treatment planning, provide clinicians with timely information about a patient’s functional and emotional status and well-being,20 and enhance family-clinician communication.21 This helps clinical staff to deliver care focused on the needs and choices of each individual child and family.22 Such use of PROMs has been evaluated in large groups of typically developing children, adolescents, and adults, and in adult patients with cancer23 and children with other long-term conditions24–27 but not in child/adolescent survivors of brain tumor or other ABI.

When selecting PROMs for a specific purpose, it is necessary to examine how robust (valid and reliable) is the measurement of HRQoL produced by such questionnaires. A number of methodological approaches are available to determine aspects of reliability and validity.28 The aim of the present systematic review was to critically appraise the psychometric properties of PROMs of HRQoL for these children, to be able to make informed decisions about the most suitable PROM for use in clinical practice.

Materials and Methods

Systematic Review

We undertook a systematic review of published evidence relating to the measurement properties of PROMs in children with brain tumors and other ABI and the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement.29 A protocol was written that specified, a priori, the inclusion criteria and methods to be used. We also used methods recommended for appraising measurement properties and for assessing the methodological quality of papers that evaluate PROMs,30 including the consensus-based standards for the selection of health status measurement instruments (COSMIN) checklist for evaluation of publications.31

Search Strategy

The search strategy was designed by an experienced information specialist (see Acknowledgments) in discussion with topic experts (K.B., C.K., and C.M.) and an experienced systematic reviewer (J.S.). Blocks of search terms were combined, including variants of “brain tumor/acquired brain injury,” “child/adolescent,” “patient reported outcome measure,” and “psychometric” and the titles of generic PROMs suitable for use in all children or in all children with long-term health conditions, as listed in the most recent systematic review focusing on HRQoL in children with disabilities.32

MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO were searched for studies published from 1992 onward in peer-reviewed journals whose purpose was to evaluate measurement properties of PROMs. An example from MEDLINE of this search strategy is shown in Appendix 1. The electronic searches were completed February 7, 2017, and updated May 28, 2019. Publication details were uploaded into an Endnote reference management database and duplicates removed. Backward citation chasing (one generation) from the reference lists of included papers was conducted by C.M. Forward citation chasing for each included study using all databases in the Web of Science cited reference search resource was conducted by S.H.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We sought published papers reporting evaluations of the measurement properties of multidimensional child (ages 5 to 18 years) self-report and/or parent-proxy report PROMs assessing health and well-being in children receiving care either for a brain tumor or other ABI of any kind (rather than for specific types of brain tumors or ABI). Evaluation of an English-language version of the PROM was a requirement for inclusion. Studies in which only part of the sample was eligible for review were included only if psychometric analyses had been conducted on the eligible subgroups within the sample. Instruments administered by an interviewer and single domain-specific questionnaires (eg, to assess only depression, fatigue, or pain) were excluded.

Study Selection

An inclusion/exclusion criteria decision chart was used to aid the selection of articles likely to yield relevant results from their titles and abstracts. The use of this chart was piloted by S.H. and K.B., who screened the first 10 articles together to test agreement over inclusion of articles. All remaining titles and abstracts were screened in batches of 40 by S.H. and, independently, by K.B. The evaluations of each batch of 40 by the 2 reviewers were then compared and any disagreements discussed and resolved. Full texts were then retrieved from this list of potential studies by S.H. K.B. then checked the list of included and excluded studies to confirm agreement. Disagreements were discussed and resolved between the reviewers.

Data Extraction, Appraisal, and Synthesis of Included Studies

Descriptive characteristics of included studies and measurement properties of the PROMs were extracted by S.H. These extracted data were checked by K.B. and the final extracted data set was agreed on in discussion with C.M. The criteria of Fitzpatrick et al (1998)33 were adopted for evaluation of the patient-based outcome measures within the extracted data set.

The COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist was used to assess the methodological quality of the included studies. The checklist is composed of 12 boxes that together cover 3 domains: content validity, internal structure, and remaining measurement properties—namely reliability, measurement error, criterion validity, hypothesis testing for construct validity, and responsiveness to change.31 Ten of the 12 boxes can be used to assess whether a study meets standards for good methodological quality, and 9 of them contain standards for the included measurement properties. These are each scored on a 4-point rating scale of the way in which each measurement property was assessed.

All the above properties were assessed (Table 1) excepting cross-cultural validity, which was not relevant because our search included only English-language reports. Criterion validity was not applicable because in the case of HRQoL there is no criterion against which HRQoL measures can be judged (except for the purpose of comparing long versions of an instrument and shortened forms of the same instrument).

Table 1.

Appraisal of Measurement Properties and Indicative Criteria (COSMIN Checklist)

| Psychometric Property | Indicative Criteria |

|---|---|

| Content validity | • Clear conceptual framework consistent with stated purpose of measurement |

| • Qualitative research with potential respondents | |

| Internal structure | • Structural validity factor analysis and post hoc tests of unidimensionality by Rasch analysis |

| • Internal consistency: Cronbach alpha coefficient > 0.7 and < 0.9 | |

| • Differential item and scale functioning between different sexes, ages, and diagnoses | |

| Reliability/Reproducibility | • Test-retest reliability: ICC > 0.7 adequate, > 0.9 excellent |

| • Proxy-reliability: child and parent-reported reliability ICC > 0.7 | |

| Measurement error/Precision | • Assessment of measurement error; floor or ceiling effects < 15%; evidence provided by Rasch analysis and/or interval level scaling |

| Hypothesis testing/Construct validity | • Hypothesis testing, with a priori hypotheses about direction and magnitude of expected effect sizes |

| Criterion validity | • Comparison of a shortened PROM to the original long version |

| (Cross-cultural validity) | • (Not assessed in this systematic review of English-language PROMs) |

| Responsiveness | • Longitudinal data about change in scores with reference to hypotheses, measurement error, and minimal important difference |

Abbreviations: COSMIN, consensus-based standards for the selection of health status measurement instruments; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure.

An overall score for the methodological quality of a study was determined by C.M. for each measurement property separately as a single rating,34 arrived at by taking the lowest rating of any of the items in a box.35 The review team then considered the evidence for each PROM and summarized in a single rating for each measurement property following methods commonly used for presentation of findings against the COSMIN criteria (Table 2). From these ratings conclusions were drawn on the extent to which each PROM could be considered robust for measuring HRQoL in children treated for brain tumors or other ABI.

Table 2.

Indices for Appraising Psychometric Properties of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (COSMIN Checklist)

| Rating | Definition | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ? | Not clearly determined | Studies were rated poor methodological quality; results not considered robust |

| – | Evidence not in favor | Studies were rated good or excellent methodological quality; results did not meet standard criteria for this property |

| ± | Conflicting evidence | Studies were rated fair, good, or excellent methodological quality; results did not consistently meet standard criteria for this property, for example, not for all domain scales |

| + | Some evidence in favor | Studies were rated fair or good methodological quality; standard criteria were met for the property |

| ++ | Some good evidence in favor | Studies were rated good or excellent methodological quality; standard criteria were met or exceeded |

| +++ | Good evidence in favor | Studies were rated good or excellent methodological quality; standard criteria were exceeded; results have been replicated |

Abbreviation: COSMIN, consensus-based standards for the selection of health status measurement instruments.

Results

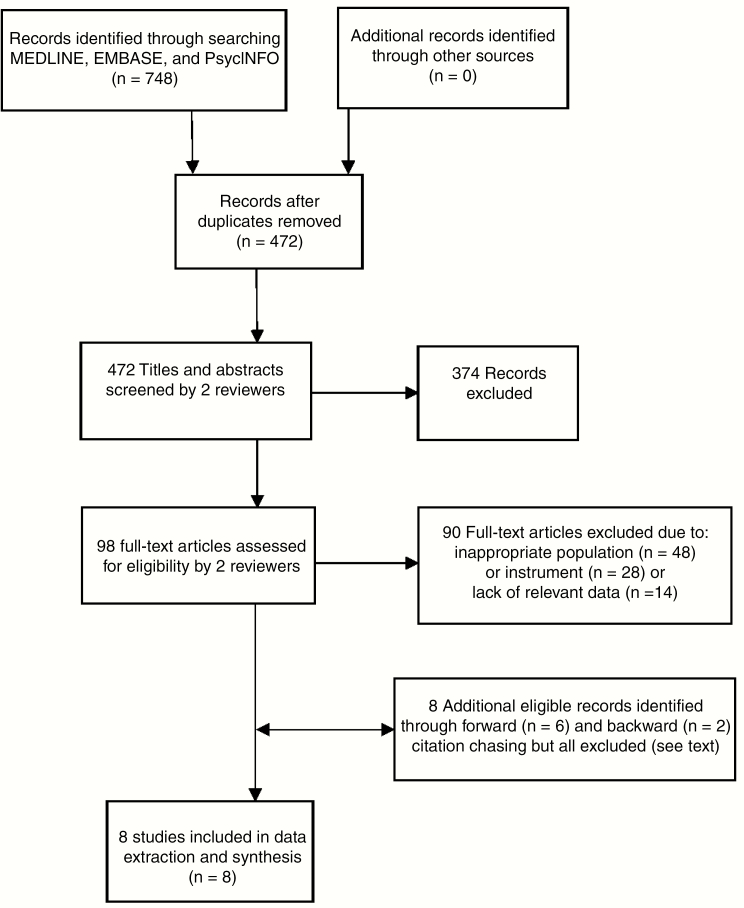

The electronic searches resulted in 472 articles after the removal of duplicates. Of these, 374 were excluded, leaving 98 potentially relevant studies whose full-text articles were retrieved. Screening of these led to the exclusion of a further 90 papers, leaving 8 studies remaining for evaluation (Fig. 1). Backward citation chasing identified 2 potentially relevant papers and forward citation chasing identified 6 potentially relevant papers, all of which were subsequently excluded because of inappropriate population (n = 4), inappropriate instrument (n = 3), or lack of relevant data (n = 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart for the identification and selection of studies evaluating psychometric properties of patient-reported outcome measures in children treated for brain tumors or acquired brain injury.

Four self-report and/or parent-proxy report PROMs—the Health Utilities Index (HUI), the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Core Module (PedsQL), the PedsQL Brain Tumor Module, and the Child and Family Follow-Up Survey (CFFS)—were evaluated and appraised in the 8 included studies (Tables 3 and 4) and these are briefly described here.

Table 3.

Studies Identified in Systematic Review as Reporting Psychometric Properties of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Children With Brain Tumors or Acquired Brain Injury up to Age 18 Years

| Acronym of PROM | Author, y | Purpose | Study Population | N | Age Range, y | Mean Age (SD), y | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HUI2/HUI3 | Barr et al, 199936 | To assess interrater agreement/reliability and construct validity | Brain tumors | 44 families | 1.7-17.9 | 9.5 | Canada |

| HUI2/HUI3 | Glaser et al, 199737 | To assess test-retest reliability when HUI completed at home and within 2 weeks, in clinic, and compare agreement between patients and parents | CNS tumors | 33 families | 5-16 | 10.7 (3.3) | England |

| HUI2/HUI3 | Glaser et al, 199938 | To assess acceptability, interobserver reliability, and interpretability of HUI2 and HUI3 in UK survivors of childhood cancer | CNS tumors | 30 families | 6-16 | 10.5 | UK |

| PedsQL (Generic Core Scales) | Bhat et al, 200539 | To assess reliability and validity | Brain tumors | 108 families, 17 parents only, 9 children only | NR | 11.8 (5.4) | USA |

| PedsQL (Generic Core Scales) | Eiser et al, 200340 | To assess reliability and validity | CNS tumors Other cancers (not included in this review) | 23 families 45 families | NR NR | 13.7 (3.1) 13.5 (3.2) | England |

| PedsQL (Brain Tumor Module) | Palmer et al, 200741 | To assess validity and internal consistency reliability | Brain tumors | 99 families | 2-18 | 9.8 | USA |

| CFFS | Bedell, 200442 | To assess preliminary findings of reliability, internal consistency, and criterion validity | ABI | 60 parents | 3-27 | 13.2 (5.2) | USA |

| CASP (section of CFFS) | Bedell, 200943 (40) | To validate CASP for young people and children with ABI | ABI, developmental disability, no identified disability, and learning/attention/sensory disability | 313 parents ABI = 176 (56%) | 3-22 | 12.8 (4.6) | USA, Canada, Australia, Israel |

Abbreviations: ABI, acquired brain injury; CASP, Child and Adolescent Scale of Participation; CFFS, Childhood and Family Follow-Up Survey; HUI2/HUI3, Health Utilities Index 2/3; N, sample size; NR, not reported; PedsQL, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America.

Table 4.

Characteristics of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Described in Studies of Children With Brain Tumors or Acquired Brain Injury up to Age 18 Years Identified by Systematic Review

| Acronym of PROM | Original Publication, y | Description | No. of Items (Type) | Scoring | Domains/scales | Recall Period | Time to Complete, min | Responder | Age Range, y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HUI2 | Torrance et al, 199644 | Generic preference-based system for measuring health status and HRQoL | 15 (multiple choice) | –0.03 (most disabled) to 1.00 (perfect health) | Sensation, mobility, emotion (distress, anxiety), cognition (learning), self-care, pain (frequency and type of control), fertilitya | 1, 2, 4 wks; usual health status | 5-10 | Proxy | ≥ 5 |

| Self | ≥ 12 | ||||||||

| HUI3 | Feeny et al, 200245 | Generic preference-based system for measuring health status and HRQoL | 15 (multiple choice) | –0.36 (most disabled) to 1.00 (perfect health) | Vision, hearing, speech, ambulation, dexterity, emotion (happiness vs depression), cognition (ability to solve day-to-day problems), pain (severity) | 1, 2, 4 wks; usual health status | 5-10 | Proxy | ≥ 5 |

| Self | ≥ 12 | ||||||||

| PedsQL 4.0 (Generic Core Scales) | Varni et al, 200146 | Generic measure of HRQoL | 23 (Likert scale) | 0 to 100, higher scores, better functioning | Physical health, psychosocial health (comprising emotional, social, and school scales) | 1 mo | 5 | Child | 5-18 |

| Parent | 2-18 | ||||||||

| PedsQL 4.0 (Brain Tumor Module) | Palmer et al, 200741 | Brain tumor– specific measure of HRQoL | 24 (Likert scale) | 0 to 100, higher scores, better functioning | Cognitive problems, pain and hurt, movement and balance, procedural anxiety, nausea, worry | 7 d | 5 | Child | 5-18 |

| Parent | 2-18 | ||||||||

| CFFS (includes CASP, CAFI, and CASE) | Bedell, 200442 | To monitor needs and outcomes of children and adolescents with ABI and their families after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation | 5 sections: I. 6 (multiple choice) II. 20 in CASP (4-point scale) and 3 open-ended III. 15 in CAFI, 18 in CASE (both 3-point scales) and 1 open-ended IV. 6 (multiple choice) V. 2 (open-ended) Total: 71 | I. Categorical II. CASP 0 to 100, higher scores, greater age-expected participation III. CAFI 0 to 100, higher scores, greater extent of problem; CASE 0 to 100, higher scores indicate greater extent of environment problem | 5 sections: I. Physical and emotional health and well-being, primary way of moving around and communicating, and medical problems or hospitalizations II. CASP including equipment, modifications, or strategies to promote participation III. CAFI and CASE IV. Educational placement, rehabilitation and health services, satisfaction with services; family’s quality of life, services, and needs V. Suggestions to improve services and additional information not already addressed | Within last y or since leaving program | 30 | Parent | 5-18 |

Abbreviations: ABI, acquired brain injury; CAFI, Child and Adolescent Factors Inventory; CASE, Child and Adolescent Scale of Environment; CASP, Child and Adolescent Scale of Participation; CFFS, Childhood and Family Follow-Up Survey; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; HUI2/HUI3, Health Utilities Index 2/3; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure; PedsQL, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory.

aThe fertility question is not integral to the questionnaire but can be added if relevant to the population (Furlong et al, 2001).

The HUI and PedsQL are generic measures of HRQoL, whereas the PedsQL Brain Tumor Module and the CFFS are disease specific. The HUI is a rating scale used to measure general health status with one question relating to HRQoL. Health utility values are commonly produced using HUI as a component of the quality-adjusted life years calculation used in population health and economics. Answers to 15 questions about health state, scored at 3 to 6 health status levels, can be grouped in 2 different ways to produce either HUI2 or HUI3 scores across 7 or 8 “attributes” of health. HUI3, for example, groups health status levels to create attribute scores for Vision, Hearing, Speech, Ambulation, Dexterity, Emotion, Cognition, and Pain.

The PedsQL is a measure of HRQoL with 23 questions across 4 core scales: Physical, Emotional, Social, and School. The 24-item PedsQL Brain Tumor Module was designed to measure HRQoL in children undergoing treatment for a brain tumor. The questions are divided between 6 subscales: cognitive problems, pain and hurt, movement and balance, procedural anxiety, nausea, and worry.

The CFFS was developed as a parent-report measure to monitor needs and outcomes of children and youth with ABI and their families. It consists of 5 sections with a total of 71 closed or open-ended questions. Section 1 asks about the child’s physical and emotional health and well-being, primary way of moving around and communicating, and medical problems or hospitalizations within the last year or since leaving the rehabilitation program. Section 2 includes the Child and Adolescent Scale of Participation (CASP) and 3 subsequent open-ended questions about equipment, modifications, or strategies that are used to promote the child’s participation. Section 3 includes the Child and Adolescent Factors Inventory (CAFI) and Child and Adolescent Scale of Environment and a question about health or medical restrictions on the child’s daily activities. Section 4 inquires about the child’s current educational placement, rehabilitation and health services, satisfaction with services, the family’s QoL, and current services and needs. Finally, Section 5 seeks suggestions to improve services at the program from where the child was discharged to better address the needs of the child and family and additional information that was not addressed in the CFFS.

Completion time for the HUI and the PedsQL (Core or brain Tumor Module) is about 5 minutes and for the CFFS about 30 minutes. Child self-report is available from age 5 years for the PedsQL modules and from age 12 years for the HUI, whereas the CFFS is available as parent-report only (Table 4). None of the studies had assessed all psychometric properties of the PROM in question.

Content Validity

This had been assessed only for the CFFS, and in this case the evidence for its validity was good.

Internal Structure

Only the CFFS had been assessed for evidence of structural validity, and there was good evidence that it possessed this property. Internal consistency had been evaluated for the CFFS (good evidence) and for the PedsQL Core and PedsQL Brain Tumor Modules (equivocal evidence) but not for the HUI (Supplementary Table S1 and Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary Appraisal of Measurement Properties of Each Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Identified in Systematic Review

| Instrument Version | Content Validity | Structural Validity | Internal Consistency | Test-Retest Reliability/Reproducibility | Proxy Reliability/Reproducibility | Measurement Error/Precision | Hypothesis Testing/Construct Validity | Responsiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HUI | ± | ± | + | + | ||||

| PedsQL | ± | ± | ± | + | ||||

| PedsQL Brain Tumor Module | ± | + | ||||||

| CFFS (including CASP section) | + | ++ | ++ | + | + |

Abbreviations: +, some evidence in favor; ++, some good evidence in favor; ±, conflicting evidence; CASP, Child and Adolescent Scale of Participation; CFFS, Childhood and Family Follow-Up Survey; HUI, Health Utilities Index; PedsQL, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory.

Other Measurement Properties

Evidence for test-retest reliability and proxy reliability was available but conflicting for the HUI and PedsQL Core module and absent for the PedsQL Brain Tumor Module and the CFFS. Favorable evidence of precision was available for the HUI but absent for the PedsQL Core and Brain Tumor Modules or the CFFS. Favorable evidence of hypothesis testing/construct validity was available for all measures. There was no evidence of responsiveness to change over time for any of the PROMs.

The methodological quality of the included studies varied from adequate to very good (Supplementary Table S2). The CFFS had had the most measurement properties evaluated, and these studies were of high quality (Supplementary Table S2).

Discussion

This is the first systematic review of evaluations of the psychometric properties of PROMs in survivors of childhood brain tumors and other ABI of childhood. It identified only 8 papers describing 4 PROMs with relevant information about their measurement properties in children treated for brain tumors or ABI. Some evidence in favor of each instrument was found with respect to those properties that had been examined, but caution is needed with respect to those properties that have not been evaluated: notably, content and structural validity for the HUI and the PedsQL, test/retest reliability and precision/measurement error for the PedsQL, and responsiveness to change over time for all measures. In contrast to the HUI and the CFFS, the self-report versions of the 2 PedsQL modules had been specifically designed for the pediatric age group.

The PedsQL Core Module has previously been reported, in the setting of orthopedic and rheumatology clinics, to be sensitive to increasing disease severity, responsive to clinical change over time, and to demonstrate effect on clinical decision making resulting in increases in HRQoL.47 The developer of the PedsQL has recommended it as a screening instrument to use in conjunction with disease-specific modules to target symptoms for interventions.48

Our strict selection criteria did not reveal any longitudinal/follow-up studies in which responsiveness to change may have been assessed incidentally, but the present study does not rule out their existence. Assessing the size of meaningful change above measurement error of the scores from PROMs is desperately needed from further research. It therefore behooves the user to design validation steps when adopting one of the questionnaires for clinical or research use to plug this evidence gap, for example, when interpreting studies that have used these questionnaires to measure change.

The validity of the use of a PROM to communicate with families and better focus their care to improve their HRQoL depends on the method by which it was developed. This method of development of a PROM is to an extent separate from its measurement properties although may be reflected in measures of content validity. These methods have been highly variable and are often not clearly specified. Thus, there would be merit in discussing further with survivors of brain tumor or other ABI and their caregivers the salience and relevance of the individual questions within questionnaires and relying on responses to individual questions rather than questionnaire scores as a means to enhance communication between care providers and service users about HRQoL. Such discussion with survivors of brain tumors or other ABI in childhood would also help to identify whether there is a need to develop a condition-specific PROM for use in child and adult survivors of brain tumor or other ABI in childhood.

Two systematic reviews of HRQoL measures in children with long-term conditions other than ABI seem to have particular relevance to selection for use in child survivors of brain tumors or other ABI. The first conducted was a systematic review of the psychometric properties of measures for use in children with neurodisability.32,49 It found evidence relating to measurement properties of 7 generic PROMs (the Child Health and Illness Profile, the Child Health Questionnaire, the Child Quality of Life questionnaire, KIDSCREEN, the PedsQL, the Student Life Satisfaction Scales, and the Youth Quality of Life Instrument), 2 chronic-generic PROMs (the DISABKIDS and the Neurology Quality of Life Measurement System), and 3 preference-based measures (HUI, the EQ-5D-Y, and the Comprehensive Health Status Classification system–Preschool). In the instance of preference-based measures, they noted a dearth of evidence of face, content, and construct validity, or test-retest reliability, and for all measures a lack of evidence for responsiveness and measurement error.

The second systematic review was of PROMs of “cancer-specific” HRQoL measures for use in children with cancer and identified 9 measures for proxy completion, of which 6 had parallel measures for self-completion by children.50 This review did not consider generic scales that had been applied in children with cancer (eg, the PedsQL Core Module) but did note that the Minneapolis-Manchester Quality of Life Instrument (MMQL-UK) child and parent versions have been validated as generic measures of QoL that can be used with healthy children and those with chronic conditions other than cancer. Adequate detail about how questionnaire items were generated from qualitative interviews was provided for only 4 questionnaires, and most did not combine this with literature review or expert opinion. Some questionnaires required further psychometric evaluation before they could be recommended, leaving just 5 recommendable measures: the Miami Pediatric Quality of Life Questionnaire (MPQS), the MMQL, the PedsQL Cancer Module, the Pediatric Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Childhood: Brain Tumor Survivor (PFACT-BT), and the Pediatric Oncology Quality of Life Scale. These questionnaires may be suitable for clinical use in children receiving care for a brain tumor or other ABI but, with the exception of the PFACT-BT, their measurement properties and performance have not been evaluated in either of these groups. The PFACT-BT is administered by an interviewer. This was an exclusion criterion for the present review and unfortunately also greatly limits the applicability of this measure.

Advantages of self-administered questionnaires include the reduction in burden associated with respondents of being able to answer at their own convenience and in their own time, the obviation of any need for a trained administrator, and, when completed online, the avoidance of transcription errors and greater efficiency and of data being entered at the moment that it is self-administered. However, the development of the questionnaires needs to be robust because measurement error may be made more likely by the absence of a trained administrator if questions are poorly worded or formatted.

However, other considerations relating to the constraints of health-care systems, including time and resources, need to be taken into account. Not all the PROMs we identified are suitable for systematic use in an outpatient clinical health-care setting. PROMs with costly licensing fees are not feasible to use in public health-care systems. where funds are limited. Also, PROMs that are lengthy to discuss will not be adopted because of clinical time constraints. PROMs also need to be relevant and suitable for follow-up consultations after treatment has ended. The CFFS appears to be the most thoroughly developed and comprehensive measure in this population but it is lengthy, at 71 questions, and the absence of any self-report version is a limitation of its use as a measure of QoL. For these reasons, the PedsQL Core Module, which is being widely used in childhood cancer research, may be the most suitable PROM for use in a clinical setting, notwithstanding the gaps in evidence regarding some of its psychometric properties.

Strengths of the present review include a comprehensive and systematic search strategy, use of standard criteria for the evaluation of the measurement properties of each PROM, and use of defined criteria to measure the quality of the studies that had been undertaken to assess these properties in participants with brain tumors or ABI in childhood. Synthesis of the findings of this review with the findings of previous reviews relating to children with other long-term conditions is also a strength. The restriction of the systematic review to evaluations of questionnaires in the English language is both a limitation of this study, in that it restricts its relevance to English-speaking service users, and a strength in that issues of cross-cultural validity apply to a much smaller extent than would be the case for an evaluation of instruments in more than one language.51

In summary, both the present systematic review of measurement properties of PROMs when used in child survivors of brain tumors or other ABI and the preceding systematic reviews of PROMs when used in survivors of childhood cancer and in children with neurodisability indicate a lack of evidence regarding measurement error or responsiveness to change and, in the case of preference-based measures, a lack of evidence of content or construct validity, or test-retest reliability. Factors contributing to this lack of evidence may include the assumption by investigators that psychometric properties shown in healthy populations also apply to survivors of brain tumors, difficulty of accessing study populations of sufficient size to reach reliable conclusions about the validity of measures used, and/or limited awareness of investigators about the importance of validating psychometric properties of those measures.

To conclude, the 4 PROMs that were identified in our systematic review and a handful of other PROMs identified in previous systematic reviews of child survivors of non-CNS cancers and of children with neurodisability had some evidence of favorable measurement properties, but this was limited and insufficient to enable selection of PROMs suitable for use in survivors of childhood brain tumors or other ABI, particularly for the measurement of change. For communication about HRQoL, the paucity of evidence of content validity in these groups suggests the need for further discussion with these patient groups to inform selection of questions that address their concerns, and we are to that end currently engaged in a qualitative study of the expressed views of brain tumor survivors. In the meantime there is clearly a need for studies that evaluate the measurement properties of those generic PROMs of HRQoL when used with these patients, whether the purpose is to inform the care of individuals or to describe the HRQoL of groups of patients.

Funding

This work was supported by The Brain Tumour Charity Quality of Life Award [GN-000366].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the help of Karen Welch, who conducted the systematic search on our behalf. Also, thanks goes to Sasja Schepers, who commented on a draft of the systematic review protocol on which the methods used were based.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1. Stiller CA. Childhood Cancer in Britain: Incidence, Survival, Mortality. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baade PD, Youlden DR, Valery PC, et al. Trends in incidence of childhood cancer in Australia, 1983-2006. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(3):620–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gatta G, Botta L, Rossi S, et al. ; EUROCARE Working Group Childhood cancer survival in Europe 1999-2007: results of EUROCARE-5—a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(1):35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Packer RJ, Gurney JG, Punyko JA, et al. Long-term neurologic and neurosensory sequelae in adult survivors of a childhood brain tumor: childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(17):3255–3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boman KK, Hovén E, Anclair M, Lannering B, Gustafsson G.. Health and persistent functional late effects in adult survivors of childhood CNS tumours: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(14):2552–2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cardarelli C, Cereda C, Masiero L, et al. Evaluation of health status and health-related quality of life in a cohort of Italian children following treatment for a primary brain tumor. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46(5):637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boman KK, Lindblad F, Hjern A. Long-term outcomes of childhood cancer survivors in Sweden: a population-based study of education, employment, and income. Cancer. 2010;116(5):1385–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bull KS, Liossi C, Culliford D, Peacock JL, Kennedy CR; Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group (CCLG) Child-related characteristics predicting subsequent health-related quality of life in 8- to 14-year-old children with and without cerebellar tumors: a prospective longitudinal study. Neurooncol Pract. 2014;1(3):114–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Macedoni-Luksic M, Jereb B, Todorovski L. Long-term sequelae in children treated for brain tumors: impairments, disability, and handicap. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;20(2):89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. NHS England. 2013/14 NHS standard contract for paediatric neurorehabilitation. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Paediatric-Neurorehabilitation.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2010-2014. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(suppl 5):v1–v88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tsze DS, Valente JH. Pediatric stroke: a review. Emerg Med Int. 2011;2011:734506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Lane MM.. Health-related quality of life measurement in pediatric clinical practice: an appraisal and precept for future research and application. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Engelen V, van Zwieten M, Koopman H, et al. The influence of patient reported outcomes on the discussion of psychosocial issues in children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(1):161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sibelli A. Quality of Life Following Treatment for a Brain Tumour: Child and Parent Perspectives. MSc. Southampton, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16. King T. A Qualitative Exploration of Longitudinal Quality of Life and Illness Experience in Childhood LGCA Brain Tumour Survivors: From a Child’s Perspective. MSc. Southampton, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.NHS England. Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/proms/. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- 18. Bull KS, Spoudeas HA, Yadegarfar G, Kennedy CR; CCLG Reduction of health status 7 years after addition of chemotherapy to craniospinal irradiation for medulloblastoma: a follow-up study in PNET 3 trial survivors on behalf of the CCLG (formerly UKCCSG). J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(27):4239–4245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Limond JA, Bull KS, Calaminus G, et al. ; Brain Tumour Quality of Survival Group, International Society of Paediatric Oncology (Europe) (SIOP-E) Quality of survival assessment in European childhood brain tumour trials, for children aged 5 years and over. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2015;19(2):202–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Santana MJ, Feeny D. Framework to assess the effects of using patient-reported outcome measures in chronic care management. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(5):1505–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ireland P, Horridge KA. The Health, Functioning and Wellbeing Summary Traffic Light Communication Tool: a survey of families’ views. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(6):661–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. NHS England. Putting Patients First: The NHS business plan for 2013/2014–2015/2016 http://www.england.nhs.uk/pp-1314-1516/. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- 23. Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, et al. Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(4):714–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tavernor L, Barron E, Rodgers J, McConachie H.. Finding out what matters: validity of quality of life measurement in young people with ASD. Child Care Health Dev. 2013;39(4):592–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haverman L, van Rossum MA, van Veenendaal M, et al. Effectiveness of a web-based application to monitor health-related quality of life. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):e533–e543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Haverman L, Engelen V, van Rossum MA, Heymans HS, Grootenhuis MA.. Monitoring health-related quality of life in paediatric practice: development of an innovative web-based application. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Snyder CF. Using patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a promising approach? J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(11):1099–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):737–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. 3rd ed. York, UK: York Publishing Services Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mokkink LB, de Vet HCW, Prinsen CAC, et al. COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1171–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Janssens A, Rogers M, Gumm R, et al. Measurement properties of multidimensional patient-reported outcome measures in neurodisability: a systematic review of evaluation studies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(5):437–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fitzpatrick R, Davey C, Buxton MJ, Jones DR.. Evaluating patient-based outcome measures for use in clinical trials. Health Technol Assess 1998;2(14):i–iv,1–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Uijen AA, Heinst CW, Schellevis FG, et al. Measurement properties of questionnaires measuring continuity of care: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e42256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, Ostelo RW, Bouter LM, de Vet HC.. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(4):651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barr RD, Simpson T, Whitton A, Rush B, Furlong W, Feeny DH.. Health-related quality of life in survivors of tumours of the central nervous system in childhood—a preference-based approach to measurement in a cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(2):248–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Glaser AW, Davies K, Walker D, Brazier D.. Influence of proxy respondents and mode of administration on health status assessment following central nervous system tumours in childhood. Qual Life Res. 1997;6(1):43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Glaser AW, Furlong W, Walker DA, et al. Applicability of the Health Utilities Index to a population of childhood survivors of central nervous system tumours in the U.K. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(2):256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bhat SR, Goodwin TL, Burwinkle TM, et al. Profile of daily life in children with brain tumors: an assessment of health-related quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5493–5500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eiser C, Vance YH, Horne B, Glaser A, Galvin H.. The value of the PedsQLTM in assessing quality of life in survivors of childhood cancer. Child Care Health Dev. 2003;29(2):95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Palmer SN, Meeske KA, Katz ER, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW.. The PedsQL Brain Tumor Module: initial reliability and validity. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(3):287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bedell GM. Developing a follow-up survey focused on participation of children and youth with acquired brain injuries after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. NeuroRehabilitation. 2004;19(3):191–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bedell G. Further validation of the Child and Adolescent Scale of Participation (CASP). Dev Neurorehabil. 2009;12(5):342–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Torrance GW, Feeny DH, Furlong WJ, Barr RD, Zhang Y, Wang Q.. Multiattribute utility function for a comprehensive health status classification system. Health Utilities Index Mark 2. Med Care. 1996;34(7):702–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Feeny D, Furlong W, Torrance GW, et al. Multiattribute and single-attribute utility functions for the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 system. Med Care. 2002;40(2):113–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39(8):800–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Varni JW, Seid M, Knight TS, Uzark K, Szer IS.. The PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales: sensitivity, responsiveness, and impact on clinical decision-making. J Behav Med. 2002;25(2):175–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M. The PedsQL as a pediatric patient-reported outcome: reliability and validity of the PedsQL Measurement Model in 25,000 children. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2005;5(6):705–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Janssens A, Rogers M, Thompson Coon J, et al. A systematic review of generic multidimensional patient-reported outcome measures for children, part II: evaluation of psychometric performance of English-language versions in a general population. Value Health. 2015;18(2):334–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Klassen AF, Strohm SJ, Maurice-Stam H, Grootenhuis MA.. Quality of life questionnaires for children with cancer and childhood cancer survivors: a review of the development of available measures. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(9):1207–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, et al. ; ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8(2):94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Furlong WJ, Feeny DH, Torrance GW, Barr RD. The Health Utilities Index (HUI®) system for assessing health-related quality of life in clinical studies. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.