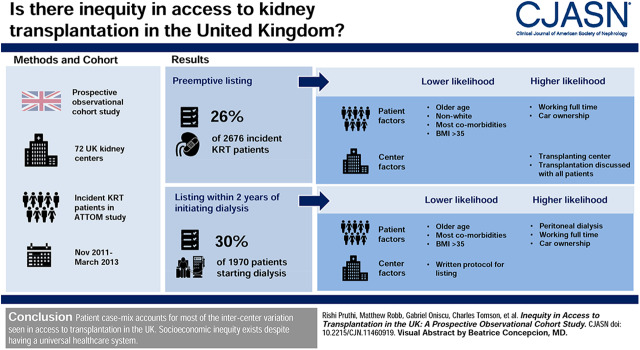

Visual Abstract

Keywords: clinical epidemiology, Epidemiology and outcomes, ethnicity, kidney transplantation, inequity, socio-economic deprivation, transplant waiting list, renal dialysis, Ethnic Groups, Minority Groups, Universal Health Care, Cohort Studies, Body Mass Index, Prospective Studies, Social Class, Renal Replacement Therapy, African Americans, Diagnosis-Related Groups, Outcome Assessment, Health Care

Abstract

Background and objectives

Despite the presence of a universal health care system, it is unclear if there is intercenter variation in access to kidney transplantation in the United Kingdom. This study aims to assess whether equity exists in access to kidney transplantation in the United Kingdom after adjustment for patient-specific factors and center practice patterns.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

In this prospective, observational cohort study including all 71 United Kingdom kidney centers, incident RRT patients recruited between November 2011 and March 2013 as part of the Access to Transplantation and Transplant Outcome Measures study were analyzed to assess preemptive listing (n=2676) and listing within 2 years of starting dialysis (n=1970) by center.

Results

Seven hundred and six participants (26%) were listed preemptively, whereas 585 (30%) were listed within 2 years of commencing dialysis. The interquartile range across centers was 6%–33% for preemptive listing and 25%–40% for listing after starting dialysis. Patient factors, including increasing age, most comorbidities, body mass index >35 kg/m2, and lower socioeconomic status, were associated with a lower likelihood of being listed and accounted for 89% and 97% of measured intercenter variation for preemptive listing and listing within 2 years of starting dialysis, respectively. Asian (odds ratio, 0.49; 95% confidence interval, 0.33 to 0.72) and Black (odds ratio, 0.43; 95% confidence interval, 0.26 to 0.71) participants were both associated with reduced access to preemptive listing; however Asian participants were associated with a higher likelihood of being listed after starting dialysis (odds ratio, 1.42; 95% confidence interval, 1.12 to 1.79). As for center factors, being registered at a transplanting center (odds ratio, 3.1; 95% confidence interval, 2.36 to 4.07) and a universal approach to discussing transplantation (odds ratio, 1.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.08 to 1.78) were associated with higher preemptive listing, whereas using a written protocol was associated negatively with listing within 2 years of starting dialysis (odds ratio, 0.7; 95% confidence interval, 0.58 to 0.9).

Conclusions

Patient case mix accounts for most of the intercenter variation seen in access to transplantation in the United Kingdom, with practice patterns also contributing some variation. Socioeconomic inequity exists despite having a universal health care system.

Introduction

In the United Kingdom, it is expected that 2.6 million adults are living with CKD stages 3–5 (1), with over 63,000 patients receiving RRT for ESKD (2). Rates of RRT have risen in most high-income countries in the last few decades (including the United Kingdom) (3,4) and are greater in lower socioeconomic groups (5,6) and in ethnic minorities (5,7). Although many undergo dialysis, it is recognized that for “suitable patients” with ESKD, kidney transplantation both confers better clinical outcomes compared with dialysis (8,9) and leads to improvements in self-reported health (10), and it is therefore the preferred RRT modality.

The United Kingdom National Health Service was founded on the principle of delivering equitable health care on the basis of need and not the ability to pay, and it was ranked first on equity in a recent international health care comparison (11). Equity is a key consideration for assessing the pathway to kidney transplantation for patients with ESKD. Achieving prompt assessment and timely activation on the transplant waiting list is crucial to accessing transplantation. Increasing length of time on dialysis adversely affects graft and patient survival (12), and deceased donor organ allocation algorithms in many countries (including the United Kingdom) give priority to those who have spent greater time on the waiting list.

Despite national clinical practice guidelines for transplant assessment, retrospective analyses of United Kingdom Renal and Transplant Registries data suggest there is variation in access to listing for transplantation between kidney centers (13−15) and that, although ethnic minorities and individuals from lower socioeconomic groups have a higher incidence of ESKD (5−7), they have reduced access to transplantation (14−17). It is not known whether this difference is due to a higher burden of comorbidity associated with ethnic minority status or lower socioeconomic status or due to differences in center practices that might disadvantage these groups (14). Studies to date have been limited in their ability to examine these factors due to their retrospective design and use of routine and limited registry data.

This study uses a prospective cohort of patients starting RRT recruited to the Access to Transplantation and Transplant Outcome Measures (ATTOM) study (18) to determine (1) if access to preemptive listing (being listed before starting dialysis) and to listing within 2 years of starting dialysis is equitable for socially deprived and ethnic minority populations in the United Kingdom after morbidity adjustment and (2) whether center-specific factors are associated with access to transplant listing.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

In the United Kingdom, there are 71 kidney centers (23 transplanting and 48 nontransplanting centers), which collectively provide RRT for all patients in the United Kingdom and manage all patients approaching ESKD. In each center, over a 12-month period between November 1, 2011 and March 31, 2013, all incident dialysis patients and incident kidney transplant recipients aged 18–75 years of age were recruited at the time of starting dialysis or transplantation as part of the ATTOM study. The ATTOM study is a national prospective cohort study investigating the factors that influence access, clinical and patient-reported outcomes, and cost-effectiveness of kidney transplantation in the United Kingdom. Dedicated research nurses collected clinical and demographic information from the case notes and local electronic databases and collected health status and well-being data from participants. The data were uploaded onto a secure website designed, developed, and maintained by the United Kingdom Renal Registry (UKRR). A full description of the ATTOM study methods and protocol has been reported previously (18).

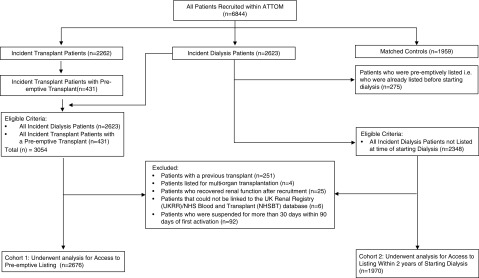

For the analysis of access to preemptive listing, all incident dialysis participants (n=2623) and all incident transplant participants with a preemptive transplant (n=431) recruited to the ATTOM study were considered for inclusion (Figure 1). Participants excluded were those with a previous transplant (n=251), those listed for multiorgan transplantation (n=4), those who recovered kidney function (n=25), and those who could not be linked to the UKRR/National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) database (n=6). Lastly, participants who were suspended from the waiting list for >30 days within 90 days of first activation (n=92) were also excluded to avoid any potential bias from centers that may activate patients on the transplant list and then immediately suspend them before more permanent activation at a later date after more formal medical assessment of the patient’s suitability.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the study recruitment of participants (with inclusion and exclusion criteria) for (1) access to preemptive listing and (2) listing after starting dialysis. ATTOM, Access to Transplantation and Transplant Outcome Measures; NHS, National Health Service.

For analysis of access to the transplant waiting list within 2 years of starting dialysis, all incident dialysis participants who were not preemptively listed (i.e., who were not listed before starting dialysis) were considered (n=2348) using the same exclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Data Collection

Patient Variables.

Demographic, socioeconomic, clinical, and comorbidity data were collected for each patient at the time of recruitment. Trained research nurses collected uniformly defined data items from patient interviews, case notes and local electronic patient information systems across the United Kingdom. Patient variables collected and analyzed included age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, and primary renal diagnosis. Several measures of socioeconomic status were also explored, including education status, employment status, accommodation, and car ownership. Civil status, number of children in household, number of adults in household, and total numbers in household were other measures. Other demographic data collected and explored included place of birth, whether English was the first language, whether any assistance was needed with reading, the length of time a patient was known to kidney services pre-RRT, and in the case of listing after starting dialysis, their dialysis modality. Full details of how these variables were categorized can be found in Supplemental Appendix 1.

Center Variables.

Thematic analysis of 45 semistructured qualitative interviews with key stakeholders and 53 patients conducted across nine kidney centers in the United Kingdom informed the development of an online survey, which was distributed to the clinical directors of all 71 United Kingdom kidney centers (19). This survey achieved a 100% response rate and was used to derive and quantify center variables for analysis in this study. Center variables examined were chosen by study investigators who examined the level of variance across center responses for each potential variable and took into account the ability to readily categorize them. A full list of center variables chosen for analysis can be found in Supplemental Appendix 1.

Outcomes.

Date of activation on the waiting list and where applicable, the date of transplantation were extracted from the United Kingdom Transplant Registry held by the Organ Donation and Transplantation Directorate of NHS Blood and Transplant. Date of death was retrieved from the UKRR database and the Scottish Renal Registry.

Statistical Methods

For access to preemptive listing, a multilevel logistic regression model was constructed to analyze the association of patient variables (level 1) and center factors (level 2). Individual participants (level 1) were nested within kidney centers (level 2) to allow for clustering of participants within centers. Analysis of each patient-level factor was adjusted for all other patient-level factors, and analysis of each center factor was adjusted for those patient-level factors found to be associated with preemptive listing. The difference in −2×log likelihood was used to compare model fit between nested models. The overall effect of center in the analysis was considered by including kidney center as a random effect. A significance level of <0.05 was taken as evidence of a significant association.

For access to the transplant waiting list within 2 years of starting dialysis, time to listing was analyzed using a multilevel Cox proportional hazards regression model. The time to listing was taken to be the time from start of dialysis to activation on the kidney transplant list. Participants were censored at 2 years or at patient death. Statistical significance was defined a priori as P=0.05. Proportional hazards assumptions were tested using Schoenfeld residuals. The presence of an overall kidney center effect was considered using a frailty term, whereas death was also considered as a competing risk using a Fine and Gray model in a separate competing risk analysis.

Multiple imputation was used to account for missing data in each analysis. For access to preemptive listing, data were missing for BMI (n=243), comorbidity (n=30), time since first seen by a nephrologist (n=24), and socioeconomic variables (n=146). For access to listing after starting dialysis, data were missing for BMI (n=220), comorbidity (n=22), and socioeconomic variables (n=104). No participants were lost to follow-up. Sensitivity analysis using complete patient analysis did not change conclusions.

All data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The baseline characteristics of participants analyzed for preemptive listing and listing within 2 years of starting dialysis are shown in Table 1. For preemptive listing, 2676 participants were analyzed following exclusion of 378 participants (12%) (see Materials and Methods). This study cohort had a median age of 57 years (interquartile range, 45–66), of which 64% were men, 81% reported their ethnicity as white, and diabetes was the most prevalent comorbidity (39%). Among sociodemographic factors, 54% of participants reported owning their own home, with 69% owning their own car.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in the Access to Transplantation and Transplant Outcome Measures study (United Kingdom) analyzed for access to preemptive kidney transplant listing and kidney transplant listing within 2 years of starting dialysis

| Variable | Access to Preemptive Listing, N (%) | Access to Listing within 2 yr of Starting Dialysis, N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | No. Preemptively Listed | Total | No. Listed within 2 yr of Starting Dialysis | |

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 55 (13.6) | 49 (12.9) | 57 (13) | 49 (14) |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 1706 (64) | 421 (60) | 1285 (65) | 406 (69) |

| Women | 970 (36) | 285 (40) | 685 (35) | 179 (31) |

| Ethnic group | ||||

| White | 2177 (81) | 611 (87) | 1566 (80) | 416 (71) |

| Asian | 293 (11) | 60 (8) | 233 (12) | 103 (18) |

| Black | 177 (7) | 31 (4) | 146 (7) | 54 (9) |

| Other | 29 (1) | 4 (1) | 25 (1) | 12 (2) |

| Primary renal disease | ||||

| Diabetes | 711 (28) | 112 (16) | 599 (30) | 119 (20) |

| GN | 428 (16) | 148 (21) | 280 (14) | 142 (24) |

| Hypertension | 171 (6) | 40 (6) | 131 (7) | 50 (9) |

| Missing | 30 (1) | 10 (1) | 20 (1) | 14 (2) |

| Other | 388 (15) | 88 (13) | 300 (15) | 75 (13) |

| Polycystic | 249 (9) | 135 (19) | 114 (6) | 56 (10) |

| Pyelonephritis | 221 (8) | 91 (13) | 130 (7) | 31 (5) |

| Renal vascular disease | 95 (4) | 12 (2) | 83 (4) | 9 (2) |

| Uncertain | 383 (14) | 70 (10) | 313 (16) | 89 (15) |

| BMI | ||||

| <20 | 165 (6) | 40 (6) | 125 (6) | 41 (7) |

| 20 to <25 | 729 (27) | 232 (33) | 497 (25) | 195 (33) |

| 25 to <30 | 771 (29) | 274 (39) | 497 (25) | 186 (32) |

| 30 to <35 | 435 (16) | 107 (15) | 328 (17) | 91 (16) |

| 35 to <40 | 202 (8) | 24 (3) | 178 (9) | 34 (6) |

| ≥40 | 131 (5) | 6 (1) | 125 (6) | 8 (1) |

| Missing | 243 (9) | 23 (3) | 220 (11) | 30 (5) |

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 1614 (60) | 552 (78) | 1065 (54) | 398 (68) |

| Type 1 | 256 (10) | 80 (11) | 176 (9) | 60 (10) |

| Type 2 | 776 (29) | 67 (10) | 709 (36) | 115 (20) |

| Missing | 27 (1.0) | 7 (1) | 20 (1) | 12 (2) |

| Heart disease | ||||

| No | 2159 (81) | 650 (92) | 1509 (77) | 508 (87) |

| Yes | 488 (18) | 48 (7) | 440 (22) | 63 (11) |

| Missing | 29 (1) | 8 (1) | 21 (1) | 14 (2) |

| Heart failure | ||||

| No | 2467 (92) | 691 (98) | 1776 (90) | 551 (94) |

| Yes | 178 (7) | 7 (1) | 171 (9) | 18 (3) |

| Missing | 31 (1) | 8 (1) | 23 (1) | 16 (3) |

| Atrial fibrillation | ||||

| No | 2547 (95) | 687 (97) | 1860 (94) | 559 (96) |

| Yes | 97 (4) | 11 (2) | 86 (4) | 10 (2) |

| Missing | 32 (1) | 8 (1) | 24 (1) | 16 (3) |

| Cardiac valve replacement | ||||

| No | 2612 (98) | 689 (98) | 1923 (98) | 568 (97) |

| Yes | 31 (1) | 7 (1) | 24 (1) | 1 (0.2) |

| Missing | 33 (1) | 10 (1) | 23 (1) | 17 (3) |

| Pacemaker | ||||

| No | 2604 (97) | 694 (98) | 1910 (97) | 567 (97) |

| Yes | 41 (2) | 4 (0.6) | 37 (2) | 2 (0.3) |

| Missing | 31 (1) | 8 (1) | 23 (1) | 16 (3) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | ||||

| No | 2422 (91) | 674 (96) | 1748 (89) | 541 (93) |

| Yes | 222 (8) | 23 (3) | 199 (10) | 28 (5) |

| Missing | 32 (1) | 9 (1) | 23 (1) | 16 (3) |

| Vascular disease | ||||

| No | 2432 (91) | 686 (97) | 1746 (89) | 545 (93) |

| Yes | 212 (8) | 12 (2) | 200 (10) | 24 (4) |

| Missing | 32 (1) | 8 (1) | 24 (1) | 16 (4) |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | ||||

| No | 2597 (97) | 693 (98) | 1904 (97) | 569 (97) |

| Yes | 46 (2) | 4 (0.6) | 42 (2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Missing | 33 (1) | 9 (1) | 24 (1) | 15 (3) |

| Respiratory disease | ||||

| No | 2335 (87) | 643 (91) | 1692 (86) | 523 (89) |

| Yes | 310 (12) | 55 (8) | 255 (13) | 47 (8) |

| Missing | 31 (1) | 8 (1) | 23 (1) | 15 (3) |

| Liver disease | ||||

| No | 2582 (97) | 691 (98) | 1891 (96) | 563 (96) |

| Yes | 64 (2) | 7 (1) | 57 (3) | 7 (1) |

| Missing | 30 (1) | 8 (1) | 22 (1) | 15 (3) |

| Blood-borne viruses | ||||

| No | 2576 (96) | 688 (98) | 1888 (96) | 562 (96) |

| Yes | 70 (3) | 10 (1) | 60 (3) | 9 (2) |

| Missing | 30 (1) | 8 (1) | 22 (1) | 14 (2) |

| Malignancy | ||||

| No | 2328 (87) | 659 93) | 1669 (85) | 545 (93) |

| Yes | 321 (12) | 39 (6) | 282 (14) | 25 (4) |

| Missing | 27 (1) | 8 (1) | 19 (1) | 14 (2) |

| Mental illness | ||||

| No | 2422 (91) | 657 (93) | 1765 (90) | 532 (91) |

| Yes | 225 (8) | 41 (6) | 184 (9) | 39 (7) |

| Missing | 29 (1) | 8 (1) | 21 (1) | 14 (2) |

| Dementia | ||||

| No | 2637 (99) | 697 (99) | 1940 (99) | 568 (97) |

| Yes | 8 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 7 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Missing | 31 (1) | 8 (1) | 23 (1) | 16 (3) |

| Smoking | ||||

| No | 1145 (43) | 364 (52) | 781 (40) | 253 (43) |

| Current | 381 (14) | 66 (9) | 315 (16) | 73 (13) |

| Ex-smoker | 763 (29) | 185 (26) | 578 (29) | 158 (27) |

| Do not know | 370 (14) | 85 (12) | 285 (15) | 93 (16) |

| Missing | 17 (0.6) | 6 (1) | 11 (0.6) | 8 (1) |

| Born in the United Kingdom | ||||

| No | 485 (18) | 86 (12) | 399 (20) | 149 (26) |

| Yes | 2032 (76) | 578 (82) | 1454 (74) | 404 (69) |

| Missing | 159 (6) | 42 (6) | 117 (6) | 32 (6) |

| English first language | ||||

| No | 325 (12) | 58 (8) | 267 (14) | 110 (19) |

| Yes | 2192 (82) | 606 (86) | 1586 (81) | 443 (76) |

| Missing | 159 (6) | 42 (6) | 117 (6) | 32 (6) |

| Read help | ||||

| No | 2058 (77) | 597 (85) | 1461 (74) | 459 (78) |

| Yes | 457 (17) | 66 (9) | 391 (20) | 94 (16) |

| Missing | 161 (6) | 43 (6) | 118 (6) | 32 (6) |

| Accommodation | ||||

| Owned by you (outright or with a mortgage) | 1436 (54) | 468 (66) | 968 (49) | 281 (48) |

| Part rent, part owned (shared ownership) | 55 (2) | 11 (2) | 44 (2) | 17 (3) |

| Rented privately from council/housing association | 861 (32) | 145 (21) | 716 (36) | 203 (35) |

| Other | 154 (6) | 37 (5) | 117 (6) | 49 (8) |

| Missing | 170 (6) | 45 (6) | 125 (6) | 35 (6) |

| Employment | ||||

| Working PT/FT | 627 (23) | 316 (45) | 311 (16) | 185 (32) |

| Long-term sick/disabled | 700 (26) | 132 (19) | 568 (29) | 156 (27) |

| Retired from paid work | 889 (33) | 124 (18) | 765 (39) | 114 (20) |

| Unemployed | 173 (7) | 37 (5) | 136 (7) | 65 (11) |

| Other | 122 (5) | 52 (7) | 70 (4) | 33 (6) |

| Missing | 165 (6) | 45 (6) | 120 (6) | 32 (6) |

| Education | ||||

| Degree, higher or NVQ 4–5 | 446 (17) | 160 (23) | 286 (15) | 137 (23) |

| GCSE, A level or NVQ 1–3 | 1051 (39) | 346 (49) | 705 (36) | 241 (41) |

| No qualifications | 1023 (38) | 160 (23) | 863 (44) | 175 (30) |

| Missing | 156 (6) | 40 (6) | 116 (6) | 32 (6) |

| Car ownership | ||||

| No | 658 (25) | 76 (11) | 582 (30) | 153 (26) |

| Yes | 1852 (69) | 586 (83) | 1266 (64) | 399 (68) |

| Missing | 166 (6) | 44 (6) | 122 (6) | 33 (6) |

| Civil status | ||||

| Single (never married) | 480 (18) | 136 (19) | 344 (17) | 136 (23) |

| Married | 1386 (52) | 388 (55) | 998 (50) | 286 (49) |

| Living with partner | 173 (7) | 64 (9) | 109 (6) | 43 (8) |

| Divorced | 238 (9) | 49 (7) | 189 (10) | 49 (8) |

| Separated (but still legally married) | 81 (3) | 12 (2) | 69 (4) | 19 (3) |

| Widowed | 148 (6) | 14 (2) | 134 (7) | 17 (3) |

| Missing | 170 (6) | 43 (6) | 127 (6) | 35 (6) |

| Children in household | ||||

| None | 1978 (74) | 472 (67) | 1506 (76) | 387 (66) |

| 1 | 264 (10) | 97 (14) | 167 (9) | 76 (13) |

| 2 or more | 265 (10) | 92 (13) | 173 (9) | 88 (15) |

| Missing | 169 (6) | 45 (6) | 124 (6) | 34 (6) |

| Adults in household | ||||

| 0–1 | 699 (26) | 127 (18) | 572 (29) | 154 (26) |

| 2 | 1261 (47) | 378 (54) | 883 (45) | 263 (45) |

| 3 or more | 545 (20) | 156 (22) | 389 (20) | 134 (23) |

| Missing | 171 (6) | 45 (6) | 126 (6) | 34 (6) |

BMI, body mass index; PT, part time; FT, full time; NVQ, National Vocational Qualification; GCSE, General Certificate of Secondary Education.

As for listing within 2 years of starting dialysis, of 2348 eligible participants, 1970 participants were analyzed following exclusion of 378 patients (16%) (see Materials and Methods). The median age of this cohort was 58 years (interquartile range, 47–67 years), of which 65% were men, 80% reported their ethnicity as white, and 45% had diabetes listed as a comorbidity. Among sociodemographic factors, 49% of participants reported owning their own home, whereas 16% of participants reported being employed. Full details of these baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Access to Preemptive Listing

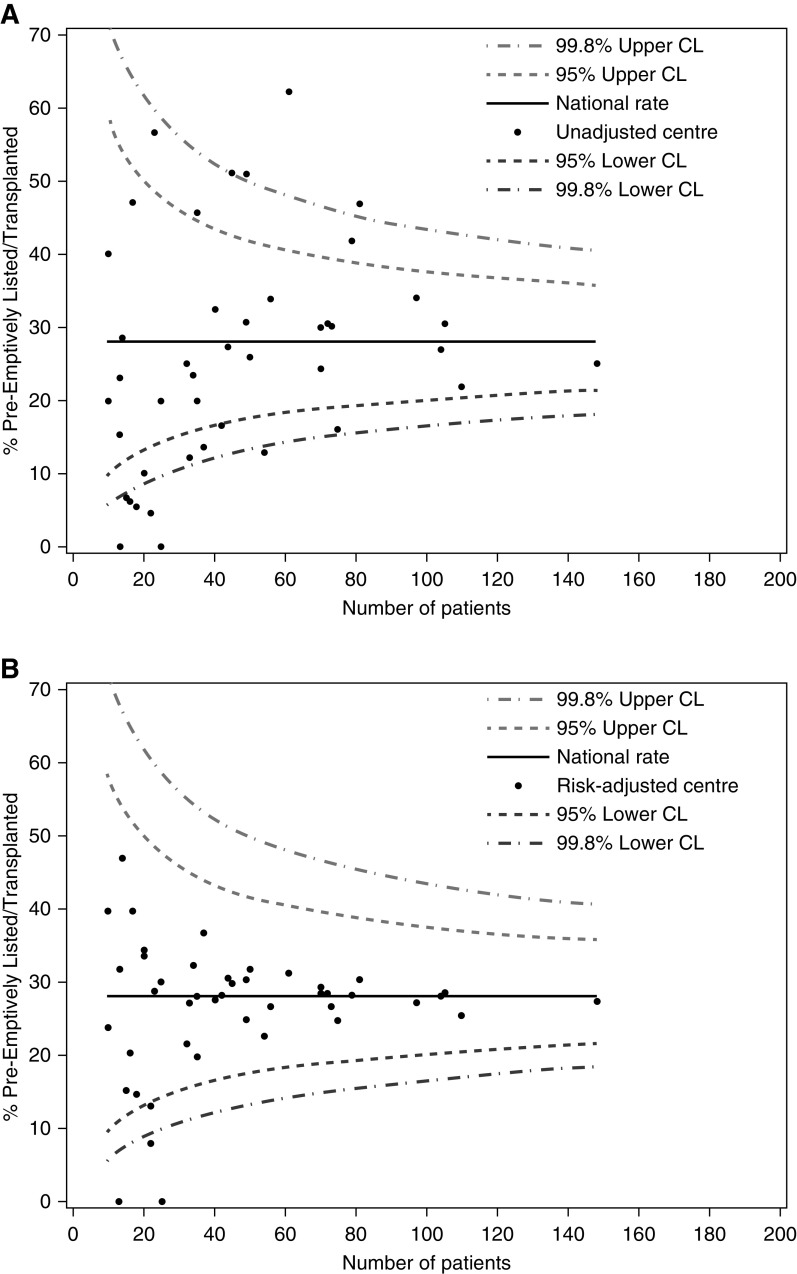

Of 2676 participants, 706 participants (26%) were preemptively listed with a mean age of 49 years. The interquartile range across centers was 6%–33%. An unadjusted funnel plot showing center variation in the percentage of participants preemptively listed is shown in Figure 2A. Associations between patient and center variables and the likelihood of being preemptively listed were characterized using univariable (Supplemental Appendices 2 and 3) and multivariable (Supplemental Appendix 4) logistic regression before proceeding to analyze them in a final multivariable logistic regression including imputed missing data (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Funnel plots showing variation in proportion of patients listed for preemptive kidney transplant by center, before, and after adjustment for patient and center factors. Centers with less than 10 observations are not shown. (A) Unadjusted center results. (B) Risk-adjusted for all patient and center factors using the mean of each adjustment variable across the cohort associated with preemptive listing as highlighted in Table 2. Number of patients denotes the number of participants from a given center who were analyzed (from the cohort of patients recruited at each center for the ATTOM study). CL, confidence limit.

Table 2.

Associations of patient-level and center-level characteristics with listing for preemptive kidney transplantation

| Variablea | N | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient variablesb | |||

| Age, yr | <0.001 | ||

| 18–29 | 149 | 1 | |

| 30–39 | 235 | 0.9 (0.51 to 1.57) | |

| 40–49 | 455 | 0.79 (0.47 to 1.32) | |

| 50–59 | 657 | 0.57 (0.34 to 0.97) | |

| 60–64 | 372 | 0.47 (0.26 to 0.87) | |

| 65–75 | 808 | 0.19 (0.1 to 0.37) | |

| Ethnic group | <0.001 | ||

| White | 2177 | 1 | |

| Asian | 293 | 0.49 (0.33 to 0.72) | |

| Black | 177 | 0.43 (0.26 to 0.71) | |

| Other | 29 | 0.23 (0.07 to 0.8) | |

| BMI | <0.001 | ||

| <20 | 184 | 0.66 (0.4 to 1.09) | |

| 20 to <25 | 798 | 1 | |

| 25 to <30 | 845 | 1.31 (0.99 to 1.73) | |

| 30 to <35 | 482 | 0.97 (0.69 to 1.38) | |

| 35 to <40 | 223 | 0.31 (0.18 to 0.54) | |

| ≥40 | 144 | 0.12 (0.05 to 0.28) | |

| Time since first seen by nephrologist, yr | <0.001 | ||

| <1 | 701 | 1 | |

| 1–3 | 619 | 8.12 (5.44 to 12.1) | |

| >3 | 1355 | 11.55 (8.05 to 16.55) | |

| Diabetes | <0.001 | ||

| No | 1626 | 1 | |

| Type 1 | 266 | 1.12 (0.76 to 1.64) | |

| Type 2 | 784 | 0.37 (0.26 to 0.52) | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | |||

| No | 2456 | 1 | |

| Yes | 220 | 0.29 (0.13 to 0.61) | 0.001 |

| Heart disease | |||

| No | 2170 | 1 | |

| Yes | 506 | 0.55 (0.36 to 0.82) | 0.004 |

| Heart failure | |||

| No | 2490 | 1 | |

| Yes | 186 | 0.25 (0.08 to 0.77) | 0.02 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | |||

| No | 2448 | 1 | |

| Yes | 228 | 0.53 (0.3 to 0.92) | 0.03 |

| Malignancy | |||

| No | 2340 | 1 | |

| Yes | 336 | 0.33 (0.2 to 0.53) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | <0.001 | ||

| No | 1148 | 1 | |

| Current | 383 | 0.53 (0.36 to 0.78) | |

| Ex-smoker | 769 | 0.95 (0.72 to 1.25) | |

| Do not know | 377 | 0.75 (0.52 to 1.07) | |

| Socioeconomic variables | |||

| Employment | <0.001 | ||

| Working full time/part time | 667 | 1 | |

| Long-term sick/disabled | 746 | 0.42 (0.3 to 0.58) | |

| Retired from paid work | 948 | 0.55 (0.37 to 0.82) | |

| Unemployed | 185 | 0.51 (0.31 to 0.85) | |

| Other | 130 | 0.93 (0.54 to 1.6) | |

| Accommodation | <0.001 | ||

| Owned by you (outright or with a mortgage) | 1533 | 1 | |

| Other | 166 | 0.58 (0.34 to 1.0) | |

| Part rent, part owned (shared ownership) | 59 | 0.32 (0.13 to 0.74) | |

| Rented privately from council/housing association | 918 | 0.55 (0.41 to 0.75) | |

| Car ownership | |||

| No | 701 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1975 | 1.98 (1.41 to 2.76) | <0.001 |

| Education | 0.08 | ||

| GCSE, A level or NVQ 1–3 | 1115 | 1.26 (0.96 to 1.67) | |

| Degree, higher or NVQ 4–5 | 477 | 1.06 (0.74 to 1.51) | |

| No qualifications | 1084 | 1 | |

| Center-level variables | |||

| Transplanting center | |||

| No | 48 | 1 | |

| Yes | 23 | 3.1 (2.36 to 4.07) | <0.001 |

| No. of consultant nephrologists | |||

| ≤6 | 30 | 1 | |

| >6 | 41 | 2.16 (1.5 to 3.1) | <0.001 |

| Transplantation discussed with all patients | |||

| No | 20 | 1 | |

| Yes | 51 | 1.39 (1.08 to 1.78) | 0.009 |

BMI, body mass index; GCSE, General Certificate of Secondary Education; NVQ, National Vocational Qualification.

Derived using multivariable logistic regression and multiple imputation; 20 imputed datasets were modeled separately and then combined to produce final parameter estimates.

Missing data were imputed for BMI (n=243), comorbidity (n=30), time since first seen by a nephrologist (n=24), and socioeconomic variables (n=146).

Several patient factors were independently associated with reduced access to preemptive listing. These included increasing age, ethnicity (both Asian and black participants), most comorbidities, having a BMI of >35, and not being seen by a nephrologist for at least 12 months before starting RRT. Lower socioeconomic status as indicated by housing tenure and car ownership status was also associated with reduced access.

Three center-level factors were negatively associated with preemptive listing: being cared for primarily in a nontransplanting center, having fewer than six whole-time equivalent consultant nephrologists in the center, and not adopting an approach where transplantation is discussed with all patients. The effect on center variation of adjusting for these center factors, along with patient factors, is shown in Figure 2B. Although intercenter variation in preemptive listing significantly reduced following the addition of center as a random effect to the model, there was still evidence of variation/unaccounted confounding (P<0.001; 1 degrees of freedom [df]). Of the 1020.9 (2679.2–1658.3) difference in −2logL between the null model and the model with patient and center variables, 89% (907) of the difference was observed when including the patient factors only (Supplemental Appendix 5).

Access to the Transplant Waiting List after Starting Dialysis

Of 1970 participants included in this analysis, 585 (30%) were listed within 2 years of starting dialysis with a mean age of 49 years. The interquartile range across centers was 25%–40%. Associations between patient and center variables and the likelihood of being listed after starting dialysis were characterized using univariable (Supplemental Appendices 6 and 7) and multivariable (Supplemental Appendix 8) Cox regression before proceeding to analyze them in a final multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model including imputed missing data (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations of patient-level and center-level characteristics with listing for kidney transplantation within 2 years of starting dialysis

| Variablea | N | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient variablesb | |||

| Age, yr | <0.001 | ||

| 18–29 | 86 | 1 | |

| 30–39 | 137 | 0.8 (0.56 to 1.12) | |

| 40–49 | 280 | 0.64 (0.46 to 0.89) | |

| 50–59 | 462 | 0.35 (0.25 to 0.49) | |

| 60–64 | 290 | 0.27 (0.18 to 0.41) | |

| 65–75 | 715 | 0.15 (0.1 to 0.23) | |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 1285 | 1 | |

| Women | 685 | 0.82 (0.68 to 0.99) | 0.04 |

| Ethnic group | 0.002 | ||

| White | 1566 | 1 | |

| Asian | 233 | 1.42 (1.12 to 1.79) | |

| Black | 146 | 1.04 (0.76 to 1.43) | |

| Other | 25 | 1.56 (0.85 to 2.87) | |

| BMI | <0.001 | ||

| <20 | 143 | 0.85 (0.6 to 1.21) | |

| 20–<25 | 561 | 1 | |

| 25–<30 | 558 | 1.15 (0.93 to 1.42) | |

| 30–<35 | 369 | 0.88 (0.67 to 1.14) | |

| 35–<40 | 200 | 0.48 (0.33 to 0.7) | |

| ≥40 | 141 | 0.15 (0.08 to 0.3) | |

| Dialysis modality | |||

| Hemodialysis | 1603 | 1 | |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 367 | 1.34 (1.1 to 1.64) | 0.004 |

| Diabetes | <0.001 | ||

| No | 1085 | 1 | |

| Type 1 | 176 | 0.76 (0.57 to 1.02) | |

| Type 2 | 709 | 0.62 (0.49 to 0.79) | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | |||

| No | 1764 | 1 | |

| Yes | 206 | 0.6 (0.37 to 0.96) | 0.04 |

| Heart disease | |||

| No | 1520 | 1 | |

| Yes | 451 | 0.8 (0.59 to 1.09) | 0.16 |

| Heart failure | |||

| No | 1797 | 1 | |

| Yes | 173 | 0.58 (0.36 to 0.93) | 0.03 |

| Blood-borne viruses | |||

| No | 1906 | 1 | |

| Yes | 64 | 0.36 (0.18 to 0.71) | 0.004 |

| Malignancy | |||

| No | 1677 | 1 | |

| Yes | 293 | 0.33 (0.2 to 0.53) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 0.05 | ||

| No | 784 | 1 | |

| Current | 316 | 0.76 (0.58 to 1.0) | |

| Ex-smoker | 582 | 1.17 (0.95 to 1.45) | |

| Do not know | 289 | 1.06 (0.82 to 1.36) | |

| Socioeconomic variables | |||

| Employment | <0.001 | ||

| Working full time/part time | 331 | 1 | |

| Long-term sick/disabled | 606 | 0.54 (0.43 to 0.68) | |

| Retired from paid work | 814 | 0.58 (0.42 to 0.8) | |

| Unemployed | 144 | 0.77 (0.56 to 1.06) | |

| Other | 75 | 0.74 (0.5 to 1.1) | |

| Accommodation | 0.009 | ||

| Owned by you (outright or with a mortgage) | 1035 | 1 | |

| Other | 126 | 0.81 (0.58 to 1.13) | |

| Part rent, part owned (shared ownership) | 47 | 1.07 (0.64 to 1.8) | |

| Rented privately from council/housing association | 762 | 0.76 (0.61 to 0.94) | |

| Car ownership | |||

| No | 619 | 0.73 (0.6 to 0.9) | 0.003 |

| Yes | 1351 | 1 | |

| Education | 0.01 | ||

| GCSE, A level or NVQ 1–3 | 749 | 1.05 (0.85 to 1.3) | |

| Degree, higher or NVQ 4–5 | 305 | 1.38 (1.07 to 1.79) | |

| No qualifications | 916 | 1 | |

| Center-level variables | |||

| Consultant nephrologists | |||

| ≤6 | 30 | 1 | |

| >6 | 41 | 1.26 (1.0 to 1.59) | 0.05 |

| MDT | |||

| No | 17 | 1 | |

| Yes | 54 | 1.23 (0.99 to 1.52) | 0.06 |

| Written protocol for listing | |||

| No | 21 | 1 | |

| Yes | 50 | 0.72 (0.58 to 0.9) | 0.003 |

BMI, body mass index; GCSE, General Certificate of Secondary Education; NVQ, National Vocational Qualification; MDT, multidisciplinary team.

Derived using multivariable Cox regression and multiple imputation; 20 imputed datasets were modeled separately and then combined to produce final parameter estimates.

Missing data were imputed for BMI (n=220), comorbidity (n=22), and socioeconomic variables (n=104).

Several patient factors were independently associated with reduced access to listing after starting dialysis. These included increasing age, women, having vascular disease, heart failure, type 2 diabetes, the presence of blood-borne viruses, a previous history of malignancy, being a current smoker, and having a BMI>35.

As with preemptive listing, lower socioeconomic status was associated with reduced access to listing after starting dialysis. Living in rented/housing association accommodation, lack of car ownership, and being long-term sick/disabled or retired from paid work compared with being in full-time/part-time employment were all negatively associated with being listed within 2 years of starting dialysis. In contrast, having a university degree, being on peritoneal dialysis as opposed to hemodialysis, and Asian ethnicity were all associated with a higher likelihood of being listed.

Among center practice patterns, having more than six consultant nephrologists in the center (odds ratio [OR], 1.3; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.00 to 1.59) was associated positively with being listed within 2 years of starting dialysis as was having a multidisciplinary team approach to listing all patients for transplantation (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.99 to 1.52). A multidisciplinary team approach was defined as having a multidisciplinary team of physicians, surgeons, and other allied health care professionals who regularly convened to discuss patients under consideration for transplant listing before activation.

Utilization of a written protocol for listing patients for transplantation (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.58 to 0.90) was negatively associated with being listed within 2 years of starting dialysis. Of the (7166.2–6566.8) 599.4 difference in −2logL between the null model and the model with patient and center variables, 97% (583.8) of the difference was observed when including the patient factors only (Supplemental Appendix 9). After adjusting center factors along with patient factors, although much of the observed intercenter variation from unadjusted analyses was again reduced, there was still evidence of a difference between the centers (P=0.04; 1 df).

Interactions and Competing Risk Analyses

When considering age as a linear factor, an interaction with type 2 diabetes was found to be important in the model (P=0.002; 1 df). The association between increasing age and time to listing was stronger in participants with type 2 diabetes (data not shown). As for the competing risk analysis, subhazard ratios derived did not highlight any significant differences.

Discussion

This national prospective cohort study of patients aged <75 years starting RRT in the United Kingdom found significant variation between kidney centers in access to preemptive listing for kidney transplantation and listing after starting dialysis. This was largely explained by patient case mix factors, although some center-level effects were also found to be important. There was evidence of socioeconomic inequity in both measures of listing, despite extensive comorbidity adjustment; ethnic minority associations were inconsistent, and inequity was only seen for preemptive listing.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strengths of this study are its prospective cohort design, national representativeness, and high levels of data completeness (especially for socioeconomic status and comorbidity), which meant that it was not subject to the inherent weaknesses of retrospective studies that have affected studies exploring access to transplantation to date. As for limitations, this study was observational, and therefore, causal relationships cannot be determined. There was also no adjustment for comorbidity severity or for pretransplant workup. In the case of access to preemptive listing, analyses could not take into account all those patients who had CKD 5 or who were approaching the need for dialysis and were being worked up for listing because these patients were not recruited as part of the ATTOM study. There may also be residual confounding factors not accounted for as suggested by the persistence of a center effect in the final models.

Comparison with Other Studies and Implications on Health Policy

Lower socioeconomic status was independently associated with both lower preemptive transplant listing and a lower likelihood of being listed after starting dialysis, even after extensive adjustment for demographic factors and comorbidity. Although this observation could arise in part from residual confounding by comorbidity due to lack of data on disease severity, this inequity is consistent with multiple studies in the United States and the United Kingdom, which have highlighted reduced access to the transplant waiting list in socially deprived patients (14,20). Similarly, several studies around the world have also shown that socioeconomically deprived individuals are less likely to undergo preemptive transplantation (21,22), although this has never been reported in the United Kingdom to date. As for potential explanations, studies, primarily in the United States, have suggested that socially deprived patients may not appreciate the advantages of kidney transplantation and may be less likely to complete the pretransplant workup (20). Additionally, clinicians may consciously or subconsciously manage patients in ways that make it less likely for socially deprived patients to be listed for transplantation (23). Another possible reason may be lower levels of health literacy among patients of lower socioeconomic status. This hypothesis is supported by studies from the United States and the United Kingdom (24,25) and may represent an area for targeted interventions to reduce inequity caused by social deprivation.

As for the association of ethnicity and the transplant pathway, this was seen to vary by measure, with both Asian and black participants being less likely to be preemptively listed compared with white participants; however, Asian ethnicity was associated with a higher likelihood of being listed after starting dialysis. Other studies have also found conflicting associations in terms of ethnicity. Many studies in the United States (16,17,20,23) and the United Kingdom (14,15) have reported that ethnic minorities have decreased access to the transplant waiting list, whereas other studies have reported equal access (26). One explanation for differing historical outcomes may be that previous studies reporting that ethnic minorities have reduced access to listing may have been confounded by combining and analyzing preemptive listing and listing after starting dialysis together, whereas in this study, they were treated independently. It is also possible that the lower likelihood of preemptive listing in ethnic minorities is partly a reflection of their lower rates of live donor transplantation found in both the United States and in the United Kingdom (27). Institutional prejudice, distrust and reluctance to engage with the medical system, cultural and religious beliefs, and lack of suitable donors or concern over a higher risk for living donors from minority ethnic backgrounds have all been cited as possible reasons for these disparities (28–31). Further research is clearly needed to understand potential reasons.

In contrast, the reasons for the observation that Asian participants had a higher likelihood of being listed after starting dialysis are unclear. Likewise, the reasons for the observation that women were negatively associated with listing after starting dialysis but not preemptive listing are uncertain; it is revealed by analyzing these cohorts separately rather than combining them as in studies to date and may be due to chance.

Although patient case mix was seen to account for the majority of intercenter variation, some center practice patterns were also seen to be associated with being listed. Being registered at a transplanting center was associated with an increase in preemptive listing but not postdialysis listing. This has been described in previous retrospective studies (24,25), and it may reflect more efficient listing processes in transplanting centers as a consequence of having access to onsite specialist clinicians to assist in assessing suitability and to onsite live donor coordinators to aid earlier identification of potential living donors.

The observation that a critical mass of consultant nephrologist availability (more than six consultant nephrologists) was independently associated with a higher likelihood of listing also suggests a direct link between improved quality of patient care (i.e., early wait-listing) and senior workforce capacity. Although we are not able to clarify why this may be the case, a possible explanation is the ability to embed subspecialist interest in transplantation and/or CKD pathway progress, which may be more likely in larger units.

The findings that discussing transplantation with all patients and not using a written protocol both improve listing are intriguing and have not been reported before. An inclusive approach to discussion about transplantation is likely to help eliminate personal bias and assist in a more patient-centered approach that may result in more open conversation as well as aid in the early identification of potential live donors. Likewise, clinicians at centers not using a written protocol (i.e., centers that do not list patients using defined criteria as part of an in-house center protocol) might benefit from listing more patients due to the ability to exercise more flexibility and their own personal clinical judgment, which would otherwise be hampered by restrictions imposed by local guidelines.

This study has shown that patient case mix and to a lesser extent, center practice patterns account for the majority of observed intercenter variation in access to preemptive listing and listing after starting dialysis in the United Kingdom. However, socioeconomic inequity exists in access to kidney transplantation in the United Kingdom despite the existence of a universal health care system. Further research is needed to understand the causal pathways between socioeconomic status and listing for transplantation including the role of health literacy in influencing access to transplantation to reduce inequity.

Disclosures

Dr. Draper was a member of United Kingdom Donation Ethics Committee 2010–2016. Dr. Fogarty reports other from Vifor Pharmaceuticals (anemia products), personal fees from ACI Clinical, other from Amicus Pharmaceuticals (treatment for Fabry disease), and personal fees from Pharmacosmos Pharmaceuticals (anemia products) outside the submitted work. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by National Institute for Health Research, Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme RP-PG-0109-10116.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the National Health Service/Health and Social Care Research Ethics Committee via Cambridgeshire Central Research Ethics Committee (Ref:11/EE/0120), and all data were collected and stored in keeping with the requirements of the United Kingdom Data Protection Act 1998.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Will Universal Access to Health Care Mean Equitable Access to Kidney Transplantation?,” on pages 752–754.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.11460919/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Appendix 1. Patient variables.

Supplemental Appendix 2. Univariate logistic regression for patient-level effects on preemptive listing.

Supplemental Appendix 3. Univariate logistic regression for center-level effects on preemptive listing/transplant, adjusting for patient-level factors.

Supplemental Appendix 4. Multivariable logistic regression model for the probability of being preemptively listed, adjusting for both patient and center factors.

Supplemental Appendix 5. Showing −2log likelihood results for statistical models analyzed for association of patient and center factors with preemptive listing.

Supplemental Appendix 6. Univariate Cox proportional hazard model for patient-level effects on time to listing within 2 years of starting dialysis.

Supplemental Appendix 7. Univariate Cox proportional hazard models for center-level effects on listing within 2 years of starting dialysis, adjusting for patient-level factors.

Supplemental Appendix 8. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards model for the probability of being listed within 2 years of starting dialysis, adjusting for both patient and center factors.

Supplemental Appendix 9. Showing −2log likelihood results for statistical models analyzed for association of patient and center factors with listing within 2 years of starting dialysis.

References

- 1.Public Health England : Chronic kidney disease prevalence model, 2014. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/612303/ChronickidneydiseaseCKDprevalencemodelbriefing.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2019

- 2.MacNeill SJ, Ford D, Evans K, Medcalf JF: Chapter 2 UK renal replacement therapy adult prevalence in 2016: National and centre-specific analyses. Nephron 139[Suppl 1]: 47–74, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilg J, Methven S, Casula A, Castledine C: UK renal registry 19th annual report: Chapter 1 UK RRT adult incidence in 2015: National and centre-specific analyses. Nephron 137[Suppl 1]: 11–44, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United States Renal Data System : 2017 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volkova N, McClellan W, Klein M, Flanders D, Kleinbaum D, Soucie JM, Presley R: Neighborhood poverty and racial differences in ESRD incidence. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 356–364, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward MM: Socioeconomic status and the incidence of ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 563–572, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roderick PJ, Raleigh VS, Hallam L, Mallick NP: The need and demand for renal replacement therapy in ethnic minorities in England. J Epidemiol Community Health 50: 334–339, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK: Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med 341: 1725–1730, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oniscu GC, Brown H, Forsythe JL: Impact of cadaveric renal transplantation on survival in patients listed for transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1859–1865, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neipp M, Karavul B, Jackobs S, Meyer zu Vilsendorf A, Richter N, Becker T, Schwarz A, Klempnauer J: Quality of life in adult transplant recipients more than 15 years after kidney transplantation. Transplantation 81: 1640–1644, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider EC, Sarnak DO, Squires D, Shah A, Doty MM: Mirror, mirror 2017: International comparison reflects flaws and opportunities for better U.S. health care, 2017. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2017/jul/mirror-mirror-2017-international-comparison-reflects-flaws-and. Accessed September 15, 2019

- 12.Meier-Kriesche HU, Kaplan B: Waiting time on dialysis as the strongest modifiable risk factor for renal transplant outcomes: A paired donor kidney analysis. Transplantation 74: 1377–1381, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor D, Robb M, Casula A, Caskey F: UK renal registry 19th annual report: Chapter 11 centre variation in access to kidney transplantation (2010-2015). Nephron 137[Suppl 1]: 259–268, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oniscu GC, Schalkwijk AA, Johnson RJ, Brown H, Forsythe JL: Equity of access to renal transplant waiting list and renal transplantation in Scotland: Cohort study. BMJ 327: 1261, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravanan R, Udayaraj U, Ansell D, Collett D, Johnson R, O’Neill J, Tomson CR, Dudley CR: Variation between centres in access to renal transplantation in UK: Longitudinal cohort study. BMJ 341: c3451, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasiske BL, London W, Ellison MD: Race and socioeconomic factors influencing early placement on the kidney transplant waiting list. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2142–2147, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeates KE, Schaubel DE, Cass A, Sequist TD, Ayanian JZ: Access to renal transplantation for minority patients with ESRD in Canada. Am J Kidney Dis 44: 1083–1089, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oniscu GC, Ravanan R, Wu D, Gibbons A, Li B, Tomson C, Forsythe JL, Bradley C, Cairns J, Dudley C, Watson CJ, Bolton EM, Draper H, Robb M, Bradbury L, Pruthi R, Metcalfe W, Fogarty D, Roderick P, Bradley JA; ATTOM Investigators : Access to transplantation and transplant outcome measures (ATTOM): Study protocol of a UK wide, in-depth, prospective cohort analysis. BMJ Open 6: e010377, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pruthi R, Tonkin-Crine S, Calestani M, Leydon G, Eyles C, Oniscu GC, Tomson C, Bradley A, Forsythe JL, Bradley C, Cairns J, Dudley C, Watson C, Draper H, Johnson R, Metcalfe W, Fogarty D, Ravanan R, Roderick PJ; ATTOM Investigators : Variation in practice patterns for listing patients for renal transplantation in the United Kingdom: A national survey. Transplantation 102: 961–968, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR: Barriers to cadaveric renal transplantation among blacks, women, and the poor. JAMA 280: 1148–1152, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grams ME, Chen BP, Coresh J, Segev DL: Preemptive deceased donor kidney transplantation: Considerations of equity and utility. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 575–582, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riffaut N, Lobbedez T, Hazzan M, Bertrand D, Westeel PF, Launoy G, Danneville I, Bouvier N, Hurault de Ligny B: Access to preemptive registration on the waiting list for renal transplantation: A hierarchical modeling approach. Transpl Int 28: 1066–1073, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navaneethan SD, Singh S: A systematic review of barriers in access to renal transplantation among African Americans in the United States. Clin Transplant 20: 769–775, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor DM, Bradley JA, Bradley C, Draper H, Johnson R, Metcalfe W, Oniscu G, Robb M, Tomson C, Watson C, Ravanan R, Roderick P; ATTOM Investigators : Limited health literacy in advanced kidney disease. Kidney Int 90: 685–695, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grubbs V, Gregorich SE, Perez-Stable EJ, Hsu CY: Health literacy and access to kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 195–200, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeffrey RF, Woodrow G, Mahler J, Johnson R, Newstead CG: Indo-Asian experience of renal transplantation in Yorkshire: Results of a 10-year survey. Transplantation 73: 1652–1657, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Udayaraj U, Ben-Shlomo Y, Roderick P, Casula A, Dudley C, Collett D, Ansell D, Tomson C, Caskey F: Social deprivation, ethnicity, and uptake of living kidney donor transplantation in the United Kingdom. Transplantation 93: 610–616, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norris KC, Agodoa LY: Unraveling the racial disparities associated with kidney disease. Kidney Int 68: 914–924, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR: Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep 118: 358–365, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bratton C, Chavin K, Baliga P: Racial disparities in organ donation and why. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 16: 243–249, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doshi M, Garg AX, Gibney E, Parikh C: Race and renal function early after live kidney donation: An analysis of the United States organ procurement and transplantation network database. Clin Transplant 24: E153–E157, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.