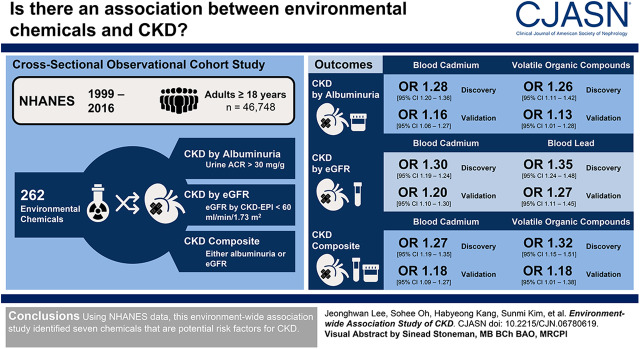

Visual Abstract

Keywords: environmental chemicals; chronic kidney disease; glomerular filtration rate; lead; cadmium; volatile organic compounds; perfluorooctanoic acid; albuminuria; phenylglyoxylic acid; Cotinine; Thiocyanates; Volatile Organic Compounds; creatinine; Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons; risk factors; Caprylates; Fluorocarbons; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic

Abstract

Background and objectives

Exposure to environmental chemicals has been recognized as one of the possible contributors to CKD. We aimed to identify environmental chemicals that are associated with CKD.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We analyzed the data obtained from a total of 46,748 adults who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1999–2016). Associations of chemicals measured in urine or blood (n=262) with albuminuria (urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g), reduced eGFR (<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), and a composite of albuminuria or reduced eGFR were tested and validated using the environment-wide association study approach.

Results

Among 262 environmental chemicals, seven (3%) chemicals showed significant associations with increased risk of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, or the composite outcome. These chemicals included metals and other chemicals that have not previously been associated with CKD. Serum and urine cotinines, blood 2,5-dimethylfuran (a volatile organic compound), and blood cadmium were associated with albuminuria. Blood lead and cadmium were associated with reduced eGFR. Blood cadmium and lead and three volatile compounds (blood 2,5-dimethylfuran, blood furan, and urinary phenylglyoxylic acid) were associated with the composite outcome. A total of 23 chemicals, including serum perfluorooctanoic acid, seven urinary metals, three urinary arsenics, urinary nitrate and thiocyanate, three urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and seven volatile organic compounds, were associated with lower risks of one or more manifestations of CKD.

Conclusions

A number of chemicals were identified as potential risk factors for CKD among the general population.

Introduction

CKD is a global public health problem (1–3). The high prevalence of CKD worldwide cannot solely be explained by well known causes such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and GN. Recently, environmental factors have been recognized as important risk factors for the development and progression process of CKD (4,5). Production and use of consumer chemicals have significantly increased in recent decades (6), and chemicals can cause adverse outcomes for human health (7,8). Epidemiologic studies have revealed that at the levels of current exposure, many chemicals are closely associated with human diseases, including neurologic, endocrinologic, and neoplastic diseases (9,10).

Various genetic and environmental factors are suggested as potential risk factors for developing CKD (11). Indeed, several environmental chemicals, including melamine and heavy metals like lead or cadmium, have long been known to be risk factors for kidney injury and CKD (12). Recently, consumer chemicals such as phthalates and bisphenol A have also been reported to be associated with CKD not only among adults, but also among children or adolescents (13). In some populations, other environmental chemicals, including perfluoroalkyl acids, dioxins, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and polychlorinated biphenyls, have been suggested as a new risk factors for CKD (14,15). However, the associations of these environmental chemicals with kidney disease parameters and CKD are not consistent according to the time points, populations, and clinical circumstances. In addition, our knowledge on the role of chemicals in the cause of CKD is quite limited, considering the growing number of chemicals being introduced in the market and used in daily lives.

In this study, the associations between various environmental chemicals measured in the general United States population and the prevalence of CKD were evaluated. For this purpose, a genome-wide association study methodology was applied for environmental chemicals instead of various genetic phenotypes, i.e., an environment-wide association study (EWAS) (16). By utilizing EWAS, hundreds of bio-monitored chemicals were tested simultaneously for their association with CKD. The results of this study will help to identify a list of potential chemicals with significant association with CKD, which can be further confirmed in follow-up epidemiologic studies and experimental mechanistic investigations.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants and Data Analyzed

We analyzed 46,748 adults (age ≥18 years) who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1999 to 2016. Among 92,062 eligible participants, 38,714 young individuals (age <18 years) were initially excluded. In addition, 6600 participants who did not have data for either urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) or eGFR were finally excluded. This cross-sectional, observational cohort study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center (approval number 07–2019–16). Information on the environmental chemicals as well as demographic and laboratory data were obtained from the NHANES database (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm; demographic, examination, questionnaire, and laboratory data set) in March 2019.

We defined hypertension as an average systolic BP of >140 mm Hg or diastolic BP of >90 mm Hg measured at least twice, history of hypertension, or currently taking antihypertensive medications. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting glucose level of >126 mg/dl, random glucose level of >200 mg/dl, or history of diabetes mellitus. Corrected serum creatinine levels were used in the survey of 1999–2000 and 2005–2006 (17,18). Serum and urine creatinine levels were measured using the Jaffe rate methods (kinetic alkaline picrate) with calibration to an isotope dilution mass spectrometry reference method. Urinary albumin levels were measured using solid-phase fluorescent immunoassay. We calculated eGFR using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration equations (19). Three CKD outcomes were assessed: albuminuria (urinary ACR ratio ≥30 mg/g), reduced eGFR (<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), and a composite outcome of albuminuria or reduced eGFR.

Measured Chemicals

In NHANES, environmental chemicals were measured in randomly selected subsamples within specific age groups. Measurements of chemicals in serum were made in samples from participants aged ≥12 years. Urine chemicals were measured in a representative one-third subsample. In the discovery set, a total of 262 environmental (minimal number of observations above 500) chemicals were included in the analysis. These chemicals could be grouped as follows: blood acrylamide and glycidamide (n=2), serum and urinary cotinines (n=2), serum dioxins (dioxins, furans, coplanar polychlorinated biphenyls; n=59), blood metals (n=4), urinary metals (n=13), urinary arsenics (n=8), urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (n=11), serum perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (n=12), urinary perchlorate/nitrate/thiocyanate (n=3), serum (n=9) and urinary pesticides (n=54), urinary phenols (n=8), urinary phytoestrogens (n=6), urinary phthalates (n=15), and blood (n=29) and urinary volatile organic compounds (n=27). Information on environmental chemicals and measurement methods is given in Supplemental Appendices 1–3.

Statistical Analyses

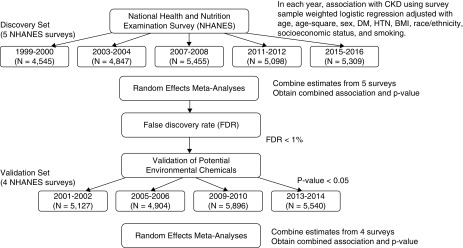

The associations between various environmental chemicals measured in the urine or blood, and CKD were assessed by the EWAS approach proposed by Patel et al. for type 2 diabetes mellitus (16,20). EWAS refers to the association study of various exposomes and disease outcomes similarly to a genome-wide association study of SNPs and disease. In general, an EWAS of environmental chemicals for specific disease requires a multiple-cycle population study such as NHANES. An EWAS integrates the multiple survey results between chemical and disease using meta-analysis methods, and validates the results using other populations. Figure 1 presents the outline of the analytic approach used in this study.

Figure 1.

Schematic flow chart for the association analysis of environmental chemicals with CKD. BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension.

We utilized the nine NHANES surveys (1999–2016) to analyze the association between environmental chemicals and CKD. The data sets from nine NHANES cycles (1999–2016) during the 18-year period were divided into the discovery and the validation sets. To reduce errors derived from chronological order, we assigned cycles in an alternate manner into the discovery set (1999–2000, 2003–2004, 2007–2008, 2011–2012, and 2015–2016) and validation set (2001–2002, 2005–2006, 2009–2010, and 2013–2014). In the discovery set, which is composed of data from the five NHANES cycles, the association between each environmental chemical and CKD was tested through survey weighted logistic regression with covariates of age, age-squared, sex, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, body mass index, race/ethnicity, smoking, and socioeconomic status. Family poverty-to-income ratio as a continuous variable was used for socioeconomic status adjustment. Considering the wide range of ages among NHANES participants, we added the age-squared term as a covariate to model the nonlinear effect of differing ages on disease outcomes. Imputation of missing values was not considered. The appropriate sample weights of the smallest subpopulation among variables were selected and adjusted among weights of mobile examination center or subsample weights of each chemicals (21). Then, the estimates from the five NHANES cycles in the discovery set were combined to obtain the meta-analytical results of the combined association and P values. Random-effects models were applied in the meta-analysis. To correct for multiple comparisons, we applied the false discovery rate in the meta-analysis. False discovery rate is one of the correction methods in multiple comparisons and is known to be less conservative compared with other correction approaches (22,23).

Heavy metal–induced nephropathy is known to share the common pathologic pathway of oxidative stress, and interaction and synergistic effects between heavy metals were recently reported (24,25). Interactions between significant heavy metal chemicals were tested with integration of interaction variable into each logistic regression from nine NHANES cycles. Pearson correlations between validated chemicals were summarized using correlation matrix (R library, corrplot). Environmental chemicals with false discovery rate <1% were considered as potential risk factors for CKD. Potential risk factors of environmental chemical for CKD identified in the discovery set were tested in the validation set, which is composed of the four NHANES cycles. P<0.05 was considered a significant cut-off value. We also performed a meta-analysis using random-effects models to combine the results of each replication of NHANES cycle in the validation set.

Continuous variables were expressed as the mean and SD (median and interquartile range, if a variable did not show normal distribution), and categorical variables were presented as frequencies with percentages. For chemicals measured in urine, creatinine-corrected concentrations were used to adjust the urinary dilution. For this purpose, all urinary chemical levels were divided by the urinary creatinine concentration. All variables were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Most environmental chemical concentrations showed right-skewed distributions; therefore, they were log-transformed. All chemical concentrations were standardized to a mean of 0 and SD of 1 to compare their effect size. R (version 3.5.2 for Windows) and SPSS software (version 21.0; IBM, Armonk, NY) were used for all analyses. A two-tailed P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 46,748 adult participants were included in this analysis. Participant demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The number of male participants was 25,709 (48%). Mean age of participants was 47±19 (range 18–85) years. Race/ethnicity of the included participants was 8979 (19%) Mexican American, 3771 (8%) Hispanic, 20,674 (44%) white, 9555 (20%) black, and 3769 (8%) other. Mean body mass index was 29±7 (range 12.0–130.2) kg/m2, mean serum creatinine level was 0.89±0.37 mg/dl, median value of urinary ACR was 6.9 (interquartile range, 4.4–13.6) mg/g, and mean eGFR was 94±24 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Hypertension and diabetes were prevalent in 39% and 13% of participants, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) participants included in an environment-wide association study

| Characteristic | All Participants (n=46,748) | Discovery Set (n=25,281) | Validation Set (n=21,467) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 47 (19) | 47 (19) | 47 (19) |

| Sex, male, % | 22,656 (48) | 12,295 (49) | 10,361 (48) |

| Body weight, kg | 80 (21) | 80 (21) | 80 (21) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29 (7) | 28 (7) | 29 (7) |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||

| Mexican American | 8979 (19) | 4867 (19) | 4112 (19) |

| Other Hispanic | 3771 (8) | 2307 (9) | 1464 (7) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 20,674 (44) | 10,544 (42) | 10,130 (47) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 9555 (20) | 5307 (21) | 4248 (20) |

| Other | 3769 (8) | 2256 (9) | 1513 (7) |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 6094 (13) | 3433 (14) | 2661 (12) |

| Hypertension, % | 18,122 (39) | 9985 (40) | 8137 (38) |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg (n=42,319) | 124 (20) | 125 (20) | 124 (19) |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg (n=42,319) | 70 (13) | 70 (13) | 70 (13) |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dl (n=22,723) | 107 (36) | 108 (38) | 105 (33) |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 4.2 (0.4) | 4.3 (0.4) | 4.2 (0.4) |

| Uric acid, mg/dl | 5.4 (1.5) | 5.4 (1.5) | 5.4 (1.5) |

| BUN, mg/dl | 13 (6) | 13 (6) | 13 (6) |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 0.89 (0.37) | 0.89 (0.37) | 0.90 (0.37) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 94 (24) | 94 (24) | 94 (24) |

| Urinary albumin-to-creatinine, mg/ga | 6.9 (4.4–13.6) | 7.0 (4.5–13.9) | 6.9 (4.4–13.2) |

| Cigarette smoking | |||

| Current smoker | 9225 (20) | 4894 (19) | 4331 (20) |

| Ex-smoker | 10,801 (23) | 5870 (23) | 4931 (23) |

| Never smoker | 23,875 (51) | 12,969 (51) | 10,906 (51) |

| Others (refused, do not know, missing) | 2847 (6) | 1548 (6) | 1299 (6) |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Family income-to-poverty ratio, family PIR (n=42,889) | 2.5 (1.6) | 2.5 (1.6) | 2.5 (1.6) |

| eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, % | 4315 (9) | 2338 (9) | 1977 (9) |

| eGFR<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, % | 1509 (3) | 816 (3) | 693 (3) |

| eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, % | 421 (1) | 230 (1) | 191 (1) |

| ACR>30 mg/g, % | 5642 (12) | 3177 (13) | 2465 (11) |

| ACR>300 mg/g, % | 958 (2) | 554 (2) | 404 (2) |

Data are shown as mean and SD or numbers and proportion (%). PIR, poverty-income ratio; ACR, albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

Median (interquartile range).

EWAS Analysis for CKD

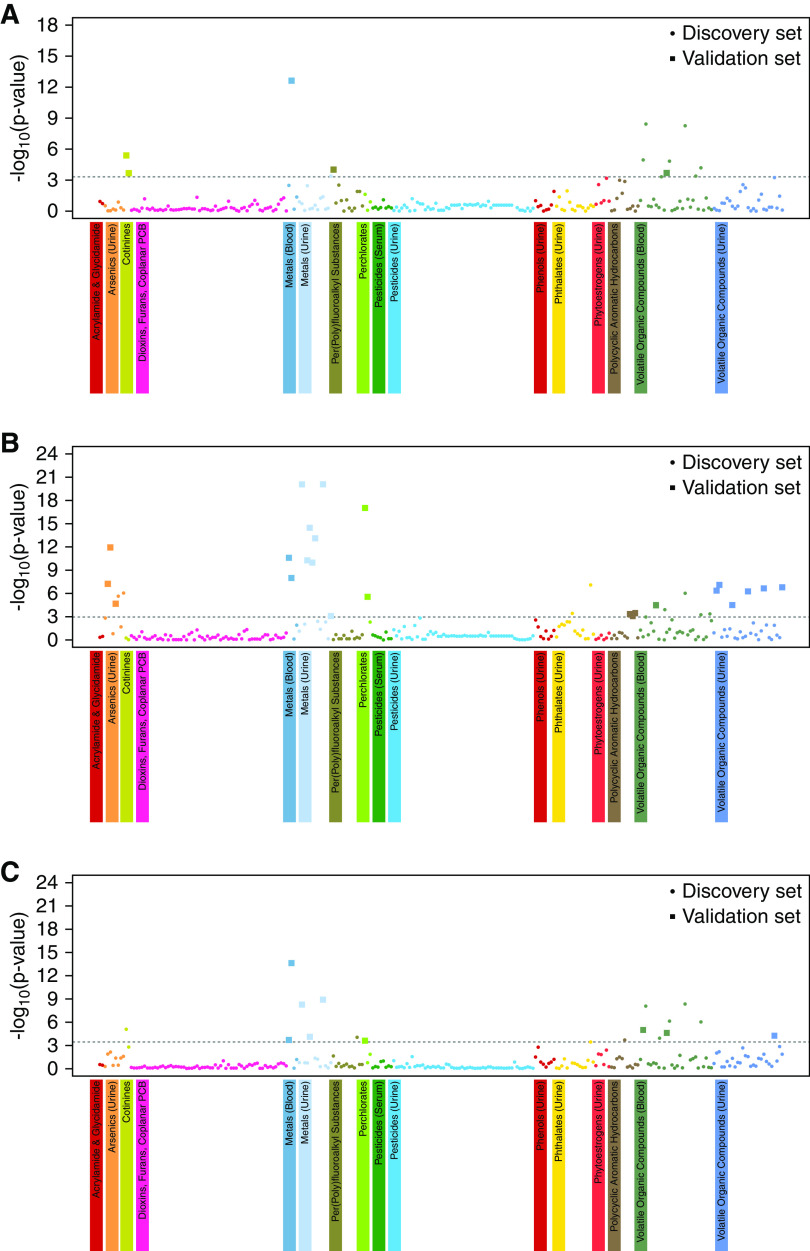

The Manhattan plots of EWAS for CKD defined by the different criteria developed in the discovery set are presented in Figure 2. Seven (3%) chemicals were associated with increased prevalence of any of the three CKD outcomes, and 23 (9%) chemicals were associated with decreased prevalence of CKD. For albuminuria, four and one chemicals were associated with increased and decreased risk of CKD, respectively. For reduced eGFR, two and 22 chemicals were associated with increased and decreased risk of CKD, respectively. For composite CKD outcome, five and four chemicals were associated with increased and decreased risk of CKD, respectively.

Figure 2.

Manhattan plot of EWAS of environmental chemicals for CKD. (A) Manhattan plot of EWAS for albuminuria. (B) Manhattan plot of EWAS for reduced eGFR. (C) Manhattan plot of EWAS for composite CKD outcome. The associations between environmental chemicals and CKD in the discovery set are presented with Manhattan plot of EWAS. y axis represent the −log10(P value) of the meta-analysis in the discovery set. x axis represents the categorized environmental chemicals. Dashed line represents the cut-off value of significance corresponding to FDR 1%. Different colors were assigned to different environmental chemical groups. Circle indicates environmental chemical tested in the discovery set. Large square indicates validated discovered (false discovery rate <1%) and validated chemicals (meta-analysis P<0.05) both in the discovery set and validation set. PCB, polychlorinated biphenyls.

Figure 2A shows the Manhattan plot of EWAS of albuminuria. Serum cotinine, urinary 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanonol, blood cadmium, urinary cadmium, serum perfluorooctanoic acid, and eight blood volatile organic compounds were discovered. Among them, blood cadmium, serum cotinine, urinary 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanonol, serum perfluorooctanoic acid, and blood 2,5-dimethylfuran were validated in the validation set. Those chemicals that showed significant associations with albuminuria are summarized in Table 2. Contrary to other discovered and validated chemicals, serum perfluorooctanoic acid was associated with a decreased risk of albuminuria.

Table 2.

Chemicals significantly associated with albuminuria in an environment-wide association study

| Environmental Chemicals | Meta-Analysis (Discovery Data Set) | Meta-Analysis (Validation Data Set) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | FDR | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Metal (blood) | ||||

| Cadmium | 1.28 (1.20 to 1.36) | 6.28×10−11 | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.27) | 9.03×10−4 |

| Cotinines | ||||

| Cotinine, serum | 1.17 (1.09 to 1.25) | 2.55×10−4 | 1.08 (1.00 to 1.15) | 3.73×10−2 |

| Nitrosamine metabolite 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL), urine | 1.21 (1.10 to 1.34) | 5.50×10−3 | 1.11 (1.01 to 1.22) | 2.93×10−2 |

| Per(poly)fluoroalkyl substances | ||||

| Perfluorooctanoic acid, serum | 0.69 (0.57 to 0.83) | 3.05×10−3 | 0.68 (0.58 to 0.80) | 1.86×10−2 |

| Volatile organic compounds (blood) | ||||

| Blood 2,5-dimethylfuran | 1.26 (1.11 to 1.42) | 5.50×10−3 | 1.13 (1.01 to 1.28) | 3.78×10−2 |

A total of 262 chemicals were evaluated, and only those that met an FDR<1% in the discovery cohort and P<0.05 in the validation cohort are included in the table. Albuminuria is defined as urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g. Each chemical is evaluated per SD increment in log-transformed blood concentration or log-transformed chemical-to-creatinine ratio. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; FDR, false discovery rate.

Figure 2B shows the Manhattan plot of EWAS of reduced eGFR. Five urinary arsenics, two blood metals, seven urinary metals, two perchlorates, two urinary phthalates (mono-benzyl and mono-carboxynonyl phthalates), three urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and six blood and six urinary volatile organic compounds were identified as significant factors in the discovery set. Among these, many chemicals were also identified as significant in the validation set, which included two blood metals (lead and cadmium), seven urinary metals (barium, cadmium, cobalt, cesium, molybdenum, lead, and thallium), three urinary arsenics (arsenocholine, arsenous acid, and arsenic acid), two urinary perchlorates (nitrate and thiocyanate), three urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (1-phenanthrene, 2-phenanthrene, and 1-pyrene), and one blood and six urinary volatile organic compounds. Environmental chemicals with a potential association with reduced eGFR are listed in Table 3. Blood lead and cadmium showed an association of increased risk of reduced eGFR. Seven urinary metals (urinary barium, cadmium, cobalt, cesium, molybdenum, lead, and thallium), three urinary arsenics (arsenocholine, arsenous acid, and arsenic acid), two urinary nitrates (nitrate and thiocyanate), three urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (1-phenanthrene, 2-phenanthrene, and 1-pyrene), and one blood and six urinary volatile organic compounds showed associations of decreased prevalence of reduced eGFR.

Table 3.

Chemicals significantly associated with reduced eGFR in an environment-wide association study

| Environmental Chemicals | Meta-Analysis (Discovery Data Set) | Meta-Analysis (Validation Data Set) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | FDR | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Metals (blood) | ||||

| Lead | 1.35 (1.24 to 1.48) | 9.45×10−10 | 1.27 (1.11 to 1.45) | 4.08×10−4 |

| Cadmium | 1.30 (1.19 to 1.42) | 2.65×10−7 | 1.20 (1.10 to 1.30) | 1.17×10−5 |

| Metals (urine) | ||||

| Barium, urine | 0.54 (0.48 to 0.62) | 1.16×10−18 | 0.51 (0.46 to 0.58) | 1.40×10−31 |

| Cadmium, urine | 0.72 (0.59 to 0.87) | 7.04×10−3 | 0.67 (0.56 to 0.81) | 1.55×10−5 |

| Cobalt, urine | 0.61 (0.53 to 0.71) | 1.81×10−9 | 0.69 (0.50 to 0.94) | 1.87×10−2 |

| Cesium, urine | 0.51 (0.43 to 0.60) | 2.27×10−13 | 0.54 (0.45 to 0.65) | 1.54×10−10 |

| Molybdenum, urine | 0.65 (0.57 to 0.74) | 3.18×10−9 | 0.77 (0.69 to 0.86) | 2.94×10−6 |

| Lead, urine | 0.53 (0.45 to 0.63) | 4.11×10−12 | 0.57 (0.49 to 0.65) | 2.71×10−15 |

| Thallium, urine | 0.53 (0.46 to 0.61) | 1.16×10−18 | 0.65 (0.53 to 0.80) | 3.91×10−5 |

| Arsenics (urine) | ||||

| Arsenocholine | 0.76 (0.68 to 0.87) | 2.60×10−4 | 0.77 (0.62 to 0.96) | 1.98×10−2 |

| Arsenous acid | 0.71 (0.63 to 0.80) | 1.37×10−6 | 0.70 (0.55 to 0.90) | 4.87×10−3 |

| Arsenic acid | 0.67 (0.60 to 0.75) | 5.13×10−11 | 0.80 (0.64 to 0.99) | 3.68×10−2 |

| Nitrates, thiocyanate, perchlorates | ||||

| Urinary nitrate | 0.55 (0.48 to 0.63) | 8.72×10−16 | 0.64 (0.55 to 0.75) | 1.81×10−8 |

| Urinary thiocyanate | 0.72 (0.62 to 0.82) | 3.39×10−5 | 0.70 (0.60 to 0.83) | 2.12×10−5 |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons | ||||

| 1-Phenanthrene, urine | 0.70 (0.57 to 0.85) | 3.95×10−3 | 0.71 (0.61 to 0.83) | 2.79×10−5 |

| 2-Phenanthrene, urine | 0.76 (0.65 to 0.89) | 7.04×10−3 | 0.72 (0.61 to 0.85) | 6.24×10−5 |

| 1-Pyrene, urine | 0.67 (0.54 to 0.83) | 3.36×10−3 | 0.59 (0.49 to 0.71) | 2.11×10−8 |

| Volatile organic compounds (blood) | ||||

| 1,2-Dichlorobenzene | 0.59 (0.47 to 0.76) | 3.18×10−4 | 0.81 (0.76 to 0.86) | 2.63×10−3 |

| Volatile organic compounds (urine) | ||||

| N-acel-S-(1,2-dichlorovinl)-L-cys | 0.63 (0.53 to 0.76) | 7.10×10−6 | 0.76 (0.65 to 0.89) | 7.89×10−4 |

| N-acel-S-(2,2-dichlorvinyl)-L-cys | 0.63 (0.53 to 0.75) | 1.66×10−6 | 0.83 (0.70 to 0.98) | 2.69×10−2 |

| 2-Amnothiazolne-4-carbxylic acid | 0.60 (0.47 to 0.76) | 3.42×10−4 | 0.68 (0.57 to 0.82) | 3.85×10−5 |

| N-ace-S-(dimethylphenyl)-L-cys | 0.67 (0.58 to 0.79) | 8.69×10−6 | 0.82 (0.69 to 0.98) | 2.82×10−2 |

| N-a-s-(1-hydrxMet)-2-prpn)-L-cys | 0.64 (0.54 to 0.76) | 4.06×10−6 | 0.82 (0.69 to 0.97) | 2.02×10−2 |

| N-acetyl-s-(trichlorovinyl)-L-cys | 0.64 (0.54 to 0.76) | 3.02×10−6 | 0.81 (0.68 to 0.97) | 1.84×10−2 |

A total of 262 chemicals were evaluated, and only those that met an FDR<1% in the discovery cohort and P<0.05 in the validation cohort are included in the table. Reduced eGFR is defined as <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Each chemical is evaluated per SD increment in log-transformed blood concentration or log-transformed chemical-to-creatinine ratio. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; FDR, false discovery rate.

Figure 2C shows the Manhattan plot of EWAS of composite CKD outcome. Serum cotinine, two blood metals (lead and cadmium), four urinary metals (barium, cesium, molybdenum, and thallium), serum perfluorooctane sulfonamide, urinary nitrate, one phthalate (mono-carboxynonyl phthalate), one urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (2-fluorene), and seven blood and one urinary volatile organic compounds were discovered in the discovery set. Of these, validated environmental chemicals were two blood metals (lead and cadmium), three urinary metals (barium, cesium, and thallium), urinary nitrate, and two blood (2,5-dimethylfuran and furan) and one urinary volatile organic compound (phenylglyoxylic acid). Environmental chemicals that were significantly associated with composite CKD outcomes are shown in Table 4. Blood lead and cadmium and two blood (2,5-dimethylfuran and furan) and one urinary volatile organic compound (phenylglyoxylic acid) were associated with an increased risk of composite CKD outcome. Three urinary metals (barium, cesium, and thallium) and urinary nitrate were associated with decreased risk of composite CKD outcomes.

Table 4.

Chemicals significantly associated with a composite CKD outcome of albuminuria or reduced eGFR in an environment-wide association study

| Environmental Chemicals | Meta-Analysis (Discovery Data Set) | Meta-Analysis (Validation Data Set) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | FDR | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Metals (blood) | ||||

| Cadmium | 1.27 (1.19 to 1.35) | 6.51×10−12 | 1.18 (1.09 to 1.27) | 2.77×10−5 |

| Lead | 1.27 (1.12 to 1.45) | 3.53×10−3 | 1.12 (1.00 to 1.24) | 4.24×10−2 |

| Metals (urine) | ||||

| Barium, urine | 0.77 (0.71 to 0.84) | 3.80×10−7 | 0.76 (0.69 to 0.84) | 1.87×10−7 |

| Cesium urine | 0.76 (0.66 to 0.87) | 1.76×10−3 | 0.73 (0.65 to 0.81) | 5.98×10−9 |

| Thallium, urine | 0.73 (0.66 to 0.81) | 1.72×10−7 | 0.75 (0.67 to 0.83) | 2.66×10−8 |

| Nitrates, thiocyanates, perchlorates | ||||

| Urinary nitrate | 0.74 (0.62 to 0.87) | 4.16×10−3 | 0.79 (0.68 to 0.93) | 4.70×10−3 |

| Volatile organic compounds (blood) | ||||

| Blood 2,5-dimethylfuran | 1.24 (1.12 to 1.36) | 6.73×10−4 | 1.12 (1.02 to 1.22) | 1.67×10−2 |

| Blood furan | 1.21 (1.11 to 1.32) | 3.23×10−4 | 1.12 (1.02 to 1.23) | 2.03×10−2 |

| Volatile organic compounds (urine) | ||||

| Phenylglyoxylic acid | 1.32 (1.15 to 1.51) | 1.38×10−3 | 1.18 (1.01 to 1.38) | 3.26×10−2 |

A total of 262 chemicals were evaluated, and only those that met an FDR<1% in the discovery cohort and P<0.05 in the validation cohort are included in the table. Albuminuria is defined as urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g and reduced eGFR is defined as <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Each chemical is evaluated per SD increment in log-transformed blood concentration or log-transformed chemical-to-creatinine ratio. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; FDR, false discovery rate.

Blood cadmium consistently shows significant association with increased prevalence of CKD in all CKD definition criteria. Blood lead showed a significant association with increased prevalence of CKD in high degrees of albuminuria (Table 5). Moreover, the odds ratios increased gradually with the increase of albuminuria and decrease of eGFR. A combined effect of blood lead and cadmium was also shown in various CKD categories defined by albuminuria (Supplemental Table 1). Blood (2,5-dimethylfuran and furan) and urinary (phenylglyoxylic acid) volatile organic compounds were associated with an increased risk of CKD defined by albuminuria or eGFR (Table 4). Increased blood 2,5-dimethylfuran levels were significantly associated with increased risk of CKD defined by low levels of albuminuria (urinary ACR of 20 and 30 mg/g) and CKD composite outcome (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 5.

Associations of blood lead and cadmium with albuminuria and reduced eGFR

| Outcome | Exposure | Meta-Analysis (Discovery Data Set) | Meta-Analysis (Validation Data Set) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | FDR | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | ||

| Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, mg/g | |||||

| ≥30 | Lead | 1.23 (1.07 to 1.42) | 3.99×10−2 | 1.08 (0.97 to 1.20) | 1.51×10−1 |

| Cadmium | 1.28 (1.20 to 1.36) | 6.28×10−11 | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.27) | 9.03×10−4 | |

| ≥300 | Lead | 1.39 (1.22 to 1.59) | 3.41×10−5 | 1.38 (1.16 to 1.63) | 2.10×10−4 |

| Cadmium | 1.42 (1.27 to 1.58) | 6.02×10−8 | 1.27 (1.00 to 1.61) | 5.41×10−2 | |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | |||||

| <60 | Lead | 1.35 (1.24 to 1.48) | 9.45×10−10 | 1.27 (1.11 to 1.45) | 4.08×10−4 |

| Cadmium | 1.30 (1.19 to 1.42) | 2.65×10−7 | 1.20 (1.10 to 1.30) | 1.17×10−5 | |

| <45 | Lead | 1.60 (1.39 to 1.85) | 5.45×10−9 | 1.63 (1.42 to 1.88) | 4.12×10−12 |

| Cadmium | 1.81 (1.58 to 2.09) | 1.80×10−14 | 1.64 (1.42 to 1.89) | 1.65×10−11 | |

| <30 | Lead | 1.98 (1.50 to 2.62) | 7.40×10−5 | 2.25 (1.75 to 2.90) | 3.67×10−10 |

| Cadmium | 2.43 (1.99 to 2.96) | 2.59×10−16 | 1.91 (1.54 to 2.37) | 3.54×10−9 | |

| Composite CKD outcomes | |||||

| Composite 1 | Lead | 1.27 (1.12 to 1.45) | 3.53×10−3 | 1.12 (1.00 to 1.24) | 4.24×10−2 |

| Cadmium | 1.27 (1.19 to 1.35) | 6.51×10−12 | 1.18 (1.09 to 1.27) | 2.77×10−5 | |

| Composite 2 | Lead | 1.43 (1.29 to 1.58) | 7.15×10−10 | 1.45 (1.29 to 1.63) | 4.91×10−10 |

| Cadmium | 1.48 (1.35 to 1.63) | 2.38×10−14 | 1.42 (1.28 to 1.57) | 2.48×10−11 | |

| Composite 3 | Lead | 1.73 (1.54 to 1.95) | 1.52×10−18 | 1.90 (1.59 to 2.28) | 3.60×10−12 |

| Cadmium | 2.01 (1.76 to 2.30) | 2.49×10−22 | 1.61 (1.35 to 1.90) | 4.51×10−8 | |

Albuminuria is defined as urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g and reduced eGFR is defined as <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Each chemical is evaluated per SD increment in log-transformed blood concentration or log-transformed chemical-to-creatinine ratio. CKD composite 1 is defined as urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (uACR) ≥30 mg/g or eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. CKD composite 2 is defined as uACR≥300 mg/g, uACR≥30 mg/g and eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, or eGFR<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2. CKD composite 3 is defined as uACR≥300 mg/g and eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, uACR≥30 mg/g and eGFR<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, or eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; FDR, false discovery rate.

Correlation between environmental chemicals are summarized with a correlation matrix (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2). Serum cotinine, urinary 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanonol, and two volatile organic compounds (blood furan and 2,5-dimethylfuran) are highly correlated with each other among chemicals associated with increased risk of CKD. Urine arsenics and urine volatile organic compounds are highly correlated among chemicals associated with decreased CKD risk.

Discussion

Our results, using the largest data set accumulated on the general United States population, clearly show that several chemicals exposed during daily lives are significantly associated with CKD. Among the 262 environmental chemicals, 30 (11%) chemicals were associated with any of the three CKD outcomes. Five (2%) chemicals were associated with albuminuria, 24 (9%) chemicals were associated with reduced eGFR, and nine (3%) chemicals were associated with composite CKD outcomes, respectively. Blood lead and cadmium, serum cotinine, urinary 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanonol, blood volatile organic compounds including 2,5-dimethylfuran and furan, and urinary phenylglyoxylic acid are associated with increased prevalence of CKD. In particular, blood lead and cadmium showed significant associations with both CKD criteria defined by albuminuria and eGFR, and the discovered volatile organic compounds showed significant associations with CKD defined by albuminuria. These chemical risk factors were identified among hundreds of chemicals measured in the general adult population using the EWAS approach. This EWAS approach provides a powerful and effective tool to identify potential risk factors for adverse outcomes of concern, from multiple candidate chemicals. In addition, visualization of the results using Manhattan plots is helpful to present the association between various environmental chemicals and a specific disease. To date, the EWAS approach has been applied to several diseases, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and semen quality (16,20,26–28).

In this study, we found that blood cadmium was consistently associated with CKD in all definition categories, and in almost all ranges of albuminuria and eGFR. Our observation also supports that coexposure to blood lead and cadmium additionally increases the risk of CKD, especially CKD defined by albuminuria. In fact, lead and cadmium exposed through environmental or occupational sources have been linked to adverse kidney effects (29), through glomerular and tubular damage and interstitial fibrosis (30–36).

Volatile organic compounds are a group of chemicals that have been used as solvents, degreasers, and cleaning agents in the industry and consumer products. Although several methods, such as detection in exhaled breath, have been suggested for assessing exposure to exposure to volatile organic compounds, their parents or metabolites in blood and urine levels have been widely used as proxy values of external exposure amount (37,38). It has been reported that some volatile organic compounds, such as furans, are typically elevated in patients with CKD with or without dialysis (39,40). Chang et al. (41) reported that occupational exposure to volatile organic compounds was associated with increased risk of CKD up to 3.84-fold. Neghab et al. (42) investigated whether occupational volatile organic compound exposure at a petrol station was significantly associated with elevated serum creatinine levels. In our investigation, two blood volatile organic compounds (furan and 2,5-dimethylfuran) and one urinary volatile organic compound (phenylglyoxylic acid) were associated with CKD as defined by albuminuria or eGFR.

Several chemicals, including perfluorooctanoic acid, were found to be associated with decreased CKD prevalence in our study. Perfluorooctanoic acid is consistently associated with the decreased prevalence of CKD defined by various range of albuminuria and lowest eGFR criteria (Supplemental Table 3). To date, no study has reported significant association between perfluorooctanoic acid levels and albuminuria in humans. This is an interesting observation because, in earlier NHANES, elevated serum perfluorooctanoic acid levels were associated with CKD on the basis of eGFR (43). Indeed, several epidemiologic studies have reported its association with decreased eGFR (44), although U-shaped association between polyfluoroalkyl substances and eGFR has also been reported (45). However, studies suggesting potential reverse causation, possibly owing to reduced kidney function, are accumulating. Polyfluoroalkyl substance concentrations were associated with decreased eGFR in people without CKD; however, these were associated with increased eGFR among patients with CKD (46). In addition, menopausal status can affect serum polyfluoroalkyl substance concentration, as menstruation is a well known excretion route of polyfluoroalkyl substance among women (47). Among adult women, it was reported that earlier menopause and reduced kidney function were the causes rather than the results of increased measured serum perfluorooctanoic acid (48). Seafood consumption may increase serum perfluorooctanoic acid levels (49,50) and should also be carefully controlled as a confounder of the causal relationship, because fish provides polyunsaturated fatty acids that are beneficial for preventing chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease (51–53). Therefore, the association between perfluorooctanoic acid and decreased CKD prevalence observed in the present population warrants further investigation with a more refined analytical design, e.g., inclusion of perfluorooctanoic acid–specific confounders in the model.

Previous studies reported associations between urinary excretion of heavy metals and increased eGFR (54–60). Jin et al. (61) observed similar findings among the 11 metals (cadmium, lead, mercury, total arsenic, dimethylarsonic acid, barium, cobalt, cesium, molybdenum, thallium, and tungsten), and urinary excretion rates of lead and cadmium decreased according to the decrease of eGFR at a similar blood lead or cadmium concentration status. These associations between urinary concentrations of heavy metals and eGFR might result from the decreased urinary excretion of chemicals in CKD patients with decreased eGFR (62,63).

Although this study used the largest number of participants, with hundreds of chemicals in consideration, as a cross-sectional association study, it has several limitations, and the observation should be interpreted with caution. First, single measurements of environmental chemicals may not represent true exposure profiles that can be compared with health outcomes. Second, we included one chemical in each logistic regression model, thus, potential interactions among the chemicals, in terms of toxicological modes of action and commonality of the exposure sources, could not be reflected and may lead to false negative or positive associations.

Our findings suggest that increased exposure to heavy metal lead, cadmium, or volatile organic compounds can be associated with increased prevalence of CKD. For each chemical that showed significant associations with CKD, further studies that investigate the pathophysiologic mechanisms of nephrotoxicity of these environmental chemicals, using in vitro or in vivo experimental models, and that validate the association of exposure to the environmental chemicals and CKD in other populations are warranted. Prospective, longitudinal, cohort studies with multiple repetitive sampling could help to support the causality of the observed relationship.

Disclosures

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the Seoul Metropolitan Government Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center (clinical research grant-in-aid 03-2019-25) and the Korean Society of Nephrology grant in 2018 (BAXTER).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the study participants.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Environmental Risks to Kidney Health,” on pages 745–746.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.06780619/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Interaction of blood lead and cadmium with the risk of CKD in whole data set according to the degree of albuminuria, eGFR, and composite categories.

Supplemental Table 2. Blood 2,5-dimethylfuran and CKD: meta-analysis results from discovery data set and validation data set according to the degree of albuminuria, eGFR, and composite categories.

Supplemental Table 3. Serum perfluorooctanoic acid and CKD: meta-analysis results from discovery data set and validation data set according to the degree of albuminuria, eGFR, and composite categories.

Supplemental Figure 1. Correlation matrix between environmental chemicals associated with increased risk of CKD.

Supplemental Figure 2. Correlation matrix between environmental chemicals associated with decreased risk of CKD.

Supplemental Appendix 1. Measurement of chemicals.

Supplemental Appendix 2. Sample weights.

Supplemental Appendix 3. List of chemicals.

References

- 1.Hill NR, Fatoba ST, Oke JL, Hirst JA, O’Callaghan CA, Lasserson DS, Hobbs FD: Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease - a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 11: e0158765, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim KM, Oh HJ, Choi HY, Lee H, Ryu DR: Impact of chronic kidney disease on mortality: A nationwide cohort study. Kidney Res Clin Pract 38: 382–390, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung HY, Choi H, Choi JY, Cho JH, Park SH, Kim CD, Ryu DR, Kim YL; ESRD Registry Committee of the Korean Society of Nephrology: Dialysis modality-related disparities in sudden cardiac death: Hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Res Clin Pract 38: 490–498, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obrador GT, Schultheiss UT, Kretzler M, Langham RG, Nangaku M, Pecoits-Filho R, Pollock C, Rossert J, Correa-Rotter R, Stenvinkel P, Walker R, Yang CW, Fox CS, Köttgen A: Genetic and environmental risk factors for chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 7: 88–106, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mrozikiewicz-Rakowska B, Maroszek P, Nehring P, Sobczyk-Kopciol A, Krzyzewska M, Kaszuba AM, Lukawska M, Chojnowska N, Kozka M, Bujalska-Zadrozny M, Ploski R, Krzymien J, Czupryniak L: Genetic and environmental predictors of chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic foot ulcer: A pilot study. J Physiol Pharmacol 66: 751–761, 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crinnion WJ: The CDC fourth national report on human exposure to environmental chemicals: What it tells us about our toxic burden and how it assist environmental medicine physicians. Altern Med Rev 15: 101–109, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bijlsma N, Cohen MM: Environmental chemical assessment in clinical practice: Unveiling the elephant in the room. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13: 181, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang RY, Needham LL: Environmental chemicals: From the environment to food, to breast milk, to the infant. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 10: 597–609, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Street ME, Angelini S, Bernasconi S, Burgio E, Cassio A, Catellani C, Cirillo F, Deodati A, Fabbrizi E, Fanos V, Gargano G, Grossi E, Iughetti L, Lazzeroni P, Mantovani A, Migliore L, Palanza P, Panzica G, Papini AM, Parmigiani S, Predieri B, Sartori C, Tridenti G, Amarri S: Current knowledge on endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) from animal biology to humans, from pregnancy to adulthood: Highlights from a National Italian meeting. Int J Mol Sci 19: E1647, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mascarelli A: Environment: Toxic effects. Nature 483: 363–365, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murea M, Ma L, Freedman BI: Genetic and environmental factors associated with type 2 diabetes and diabetic vascular complications. Rev Diabet Stud 9: 6–22, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vervaet BA, D’Haese PC, Verhulst A: Environmental toxin-induced acute kidney injury. Clin Kidney J 10: 747–758, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kataria A, Trasande L, Trachtman H: The effects of environmental chemicals on renal function. Nat Rev Nephrol 11: 610–625, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everett CJ, Thompson OM: Dioxins, furans and dioxin-like PCBs in human blood: Causes or consequences of diabetic nephropathy? Environ Res 132: 126–131, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang JW, Ou HY, Chen HL, Su HJ, Lee CC: Hyperuricemia after exposure to polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans near a highly contaminated area. Epidemiology 24: 582–589, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel CJ, Bhattacharya J, Butte AJ: An Environment-Wide Association Study (EWAS) on type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One 5: e10746, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoerger TJ, Simpson SA, Yarnoff BO, Pavkov ME, Ríos Burrows N, Saydah SH, Williams DE, Zhuo X: The future burden of CKD in the United States: A simulation model for the CDC CKD initiative. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 403–411, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selvin E, Manzi J, Stevens LA, Van Lente F, Lacher DA, Levey AS, Coresh J: Calibration of serum creatinine in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 1988-1994, 1999-2004. Am J Kidney Dis 50: 918–926, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration): A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGinnis DP, Brownstein JS, Patel CJ: Environment-wide association study of blood pressure in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1999-2012). Sci Rep 6: 30373, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Overview of NHANES survey design and weights, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/dietary/SurveyOrientation/SurveyDesign/intro.htm. Accessed June 4, 2019

- 22.Storey JD, Tibshirani R: Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 9440–9445, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benjamini Y, Cohen R: Weighted false discovery rate controlling procedures for clinical trials. Biostatistics 18: 91–104, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai TL, Kuo CC, Pan WH, Chung YT, Chen CY, Wu TN, Wang SL: The decline in kidney function with chromium exposure is exacerbated with co-exposure to lead and cadmium. Kidney Int 92: 710–720, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lunyera J, Smith SR: Heavy metal nephropathy: Considerations for exposure analysis. Kidney Int 92: 548–550, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung MK, Buck Louis GM, Kannan K, Patel CJ: Exposome-wide association study of semen quality: Systematic discovery of endocrine disrupting chemical biomarkers in fertility require large sample sizes. Environ Int 125: 505–514, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall MA, Dudek SM, Goodloe R, Crawford DC, Pendergrass SA, Peissig P, Brilliant M, McCarty CA, Ritchie MD: Environment-wide association study (EWAS) for type 2 diabetes in the marshfield personalized medicine research project biobank. Pac Symp Biocomput (2013): 200–211, 2014 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lind PM, Risérus U, Salihovic S, Bavel B, Lind L: An environmental wide association study (EWAS) approach to the metabolic syndrome. Environ Int 55: 1–8, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rastogi SK: Renal effects of environmental and occupational lead exposure. Indian J Occup Environ Med 12: 103–106, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orr SE, Bridges CC: Chronic kidney disease and exposure to nephrotoxic metals. Int J Mol Sci 18: E1039, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alissa EM, Ferns GA: Heavy metal poisoning and cardiovascular disease. J Toxicol 2011: 870125, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hara A, Yang WY, Petit T, Zhang ZY, Gu YM, Wei FF, Jacobs L, Odili AN, Thijs L, Nawrot TS, Staessen JA: Incidence of nephrolithiasis in relation to environmental exposure to lead and cadmium in a population study. Environ Res 145: 1–8, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.García-Esquinas E, Navas-Acien A, Pérez-Gómez B, Artalejo FR: Association of lead and cadmium exposure with frailty in US older adults. Environ Res 137: 424–431, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim NH, Hyun YY, Lee KB, Chang Y, Ryu S, Oh KH, Ahn C: Environmental heavy metal exposure and chronic kidney disease in the general population. J Korean Med Sci 30: 272–277, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fadrowski JJ, Navas-Acien A, Tellez-Plaza M, Guallar E, Weaver VM, Furth SL: Blood lead level and kidney function in US adolescents: The third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med 170: 75–82, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Navas-Acien A, Tellez-Plaza M, Guallar E, Muntner P, Silbergeld E, Jaar B, Weaver V: Blood cadmium and lead and chronic kidney disease in US adults: A joint analysis. Am J Epidemiol 170: 1156–1164, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashley DL, Bonin MA, Cardinali FL, McCraw JM, Wooten JV: Measurement of volatile organic compounds in human blood. Environ Health Perspect 104[Suppl 5]: 871–877, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding YS, Blount BC, Valentin-Blasini L, Applewhite HS, Xia Y, Watson CH, Ashley DL: Simultaneous determination of six mercapturic acid metabolites of volatile organic compounds in human urine. Chem Res Toxicol 22: 1018–1025, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mochalski P, King J, Haas M, Unterkofler K, Amann A, Mayer G: Blood and breath profiles of volatile organic compounds in patients with end-stage renal disease. BMC Nephrol 15: 43, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pagonas N, Vautz W, Seifert L, Slodzinski R, Jankowski J, Zidek W, Westhoff TH: Volatile organic compounds in uremia. PLoS One 7: e46258, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang TY, Huang KH, Liu CS, Shie RH, Chao KP, Hsu WH, Bao BY: Exposure to volatile organic compounds and kidney dysfunction in thin film transistor liquid crystal display (TFT-LCD) workers. J Hazard Mater 178: 934–940, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neghab M, Hosseinzadeh K, Hassanzadeh J: Early liver and kidney dysfunction associated with occupational exposure to sub-threshold limit value levels of benzene, toluene, and xylenes in unleaded petrol. Saf Health Work 6: 312–316, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shankar A, Xiao J, Ducatman A: Perfluoroalkyl chemicals and chronic kidney disease in US adults. Am J Epidemiol 174: 893–900, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stanifer JW, Stapleton HM, Souma T, Wittmer A, Zhao X, Boulware LE: Perfluorinated chemicals as emerging environmental threats to kidney health: A scoping review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1479–1492, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jain RB, Ducatman A: Perfluoroalkyl substances follow inverted U-shaped distributions across various stages of glomerular function: Implications for future research. Environ Res 169: 476–482, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Conway BN, Badders AN, Costacou T, Arthur JM, Innes KE: Perfluoroalkyl substances and kidney function in chronic kidney disease, anemia, and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 11: 707–716, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lorber M, Eaglesham GE, Hobson P, Toms LM, Mueller JF, Thompson JS: The effect of ongoing blood loss on human serum concentrations of perfluorinated acids. Chemosphere 118: 170–177, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dhingra R, Winquist A, Darrow LA, Klein M, Steenland K: A study of reverse causation: Examining the associations of perfluorooctanoic acid serum levels with two outcomes. Environ Health Perspect 125: 416–421, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haug LS, Thomsen C, Brantsaeter AL, Kvalem HE, Haugen M, Becher G, Alexander J, Meltzer HM, Knutsen HK: Diet and particularly seafood are major sources of perfluorinated compounds in humans. Environ Int 36: 772–778, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fromme H, Tittlemier SA, Völkel W, Wilhelm M, Twardella D: Perfluorinated compounds--exposure assessment for the general population in Western countries. Int J Hyg Environ Health 212: 239–270, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dallaire R, Dewailly É, Ayotte P, Forget-Dubois N, Jacobson SW, Jacobson JL, Muckle G: Exposure to organochlorines and mercury through fish and marine mammal consumption: Associations with growth and duration of gestation among inuit newborns. Environ Int 54: 85–91, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choi AL, Cordier S, Weihe P, Grandjean P: Negative confounding in the evaluation of toxicity: The case of methylmercury in fish and seafood. Crit Rev Toxicol 38: 877–893, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guallar E, Sanz-Gallardo MI, van’t Veer P, Bode P, Aro A, Gómez-Aracena J, Kark JD, Riemersma RA, Martín-Moreno JM, Kok FJ; Heavy Metals and Myocardial Infarction Study Group: Mercury, fish oils, and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 347: 1747–1754, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao Y, Zhu X, Shrubsole MJ, Fan L, Xia Z, Harris RC, Hou L, Dai Q: The modifying effect of kidney function on the association of cadmium exposure with blood pressure and cardiovascular mortality: NHANES 1999-2010. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 353: 15–22, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buser MC, Ingber SZ, Raines N, Fowler DA, Scinicariello F: Urinary and blood cadmium and lead and kidney function: NHANES 2007-2012. Int J Hyg Environ Health 219: 261–267, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zheng LY, Umans JG, Yeh F, Francesconi KA, Goessler W, Silbergeld EK, Bandeen-Roche K, Guallar E, Howard BV, Weaver VM, Navas-Acien A: The association of urine arsenic with prevalent and incident chronic kidney disease: Evidence from the Strong Heart Study. Epidemiology 26: 601–612, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shelley R, Kim NS, Parsons P, Lee BK, Jaar B, Fadrowski J, Agnew J, Matanoski GM, Schwartz BS, Steuerwald A, Todd A, Simon D, Weaver VM: Associations of multiple metals with kidney outcomes in lead workers. Occup Environ Med 69: 727–735, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weaver VM, Kim NS, Lee BK, Parsons PJ, Spector J, Fadrowski J, Jaar BG, Steuerwald AJ, Todd AC, Simon D, Schwartz BS: Differences in urine cadmium associations with kidney outcomes based on serum creatinine and cystatin C. Environ Res 111: 1236–1242, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weaver VM, Kim NS, Jaar BG, Schwartz BS, Parsons PJ, Steuerwald AJ, Todd AC, Simon D, Lee BK: Associations of low-level urine cadmium with kidney function in lead workers. Occup Environ Med 68: 250–256, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferraro PM, Costanzi S, Naticchia A, Sturniolo A, Gambaro G: Low level exposure to cadmium increases the risk of chronic kidney disease: Analysis of the NHANES 1999-2006. BMC Public Health 10: 304, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jin R, Zhu X, Shrubsole MJ, Yu C, Xia Z, Dai Q: Associations of renal function with urinary excretion of metals: Evidence from NHANES 2003-2012. Environ Int 121: 1355–1362, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lea-Henry TN, Carland JE, Stocker SL, Sevastos J, Roberts DM: Clinical pharmacokinetics in kidney disease: Fundamental principles. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1085–1095, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Suchy-Dicey AM, Laha T, Hoofnagle A, Newitt R, Sirich TL, Meyer TW, Thummel KE, Yanez ND, Himmelfarb J, Weiss NS, Kestenbaum BR: Tubular secretion in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 2148–2155, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.