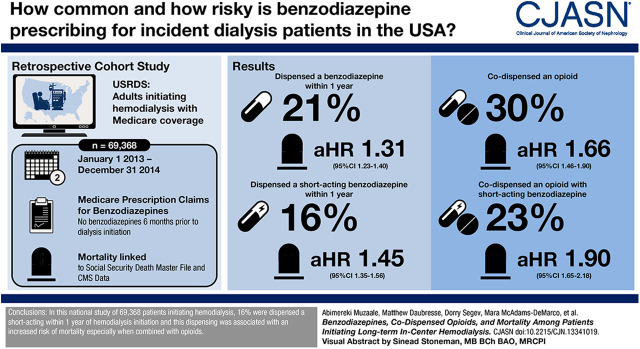

Visual Abstract

Keywords: Benzodiazepines, Analgesics, Opioid, Medicare, Proportional Hazards Models, Opioid Epidemic, Follow-Up Studies, renal dialysis, dialysis, Cohort Studies, Prescriptions, Records

Abstract

Background and objectives

Mortality from benzodiazepine/opioid interactions is a growing concern in light of the opioid epidemic. Patients on hemodialysis suffer from a high burden of physical/psychiatric conditions, which are treated with benzodiazepines, and they are three times more likely to be prescribed opioids than the general population. Therefore, we studied mortality risk associated with short- and long-acting benzodiazepines and their interaction with opioids among adults initiating hemodialysis.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

The cohort of 69,368 adults initiating hemodialysis (January 2013 to December 2014) was assembled by linking US Renal Data System records to Medicare claims. Medicare claims were used to identify dispensed benzodiazepines and opioids. Using adjusted Cox proportional hazards models, we estimated the mortality risk associated with benzodiazepines (time varying) and tested whether the benzodiazepine-related mortality risk differed by opioid codispensing.

Results

Within 1 year of hemodialysis initiation, 10,854 (16%) patients were dispensed a short-acting benzodiazepine, and 3262 (5%) patients were dispensed a long-acting benzodiazepine. Among those who were dispensed a benzodiazepine during follow-up, codispensing of opioids and short-acting benzodiazepines occurred among 3819 (26%) patients, and codispensing of opioids and long-acting benzodiazepines occurred among 1238 (8%) patients. Patients with an opioid prescription were more likely to be subsequently dispensed a short-acting benzodiazepine (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.66; 95% confidence interval, 1.59 to 1.74) or a long-acting benzodiazepine (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.11; 95% confidence interval, 1.03 to 1.20). Patients dispensed a short-acting benzodiazepine were at a 1.45-fold (95% confidence interval, 1.35 to 1.56) higher mortality risk compared with those without a short-acting benzodiazepine; among those with opioid codispensing, this risk was 1.90-fold (95% confidence interval, 1.65 to 2.18; Pinteraction<0.001). In contrast, long-acting benzodiazepine dispensing was inversely associated with mortality (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.72 to 0.99) compared with no dispensing of long-acting benzodiazepine; there was no differential risk by opioid dispensing (Pinteraction=0.72).

Conclusions

Codispensing of opioids and short-acting benzodiazepines is common among patients on dialysis, and it is associated with higher risk of death.

Introduction

Benzodiazepines are a commonly prescribed class of psychotropic medications (1,2), and use in the general population has increased considerably over time (3). In 2013, 5.6% of adults filled a benzodiazepines prescription (4), and white patients most commonly receive benzodiazepines (5). Patients on hemodialysis often suffer a high burden of physical and psychiatric conditions, including anxiety (6), insomnia/sleep disorders (7), alcohol dependence (8), and neuropathic pain (9,10), all of which are indications for benzodiazepines. Although it is likely that there is a high burden of benzodiazepine use in this population, it is unclear how many and which patients on hemodialysis receive benzodiazepines.

Benzodiazepine-related mortality has been identified as a growing concern, particularly among white adults (3,4,11,12). Although the mortality risk associated with benzodiazepine use in the general population is likely minimal (12), it is elevated when combined with opioids (3,11,13). Specifically, benzodiazepines interact with opioids and enhance the respiratory depressant effects of opioids; clinical recommendations as well as opioid labeling suggest avoiding this coprescribing (14). Two studies from over 15 years ago, one study of 7475 international patients on prevalent hemodialysis between 1999 and 2004 and one study of 3690 patients on incident dialysis between 1996 and 1997 (15,16), suggest that benzodiazepines may be associated with mortality; however, less is known about the risk associated with coprescribing. Patients on hemodialysis may be particularly at risk of coprescribing because they are three times as likely to be prescribed opioids than the general population (17). Therefore, patients on hemodialysis are likely at elevated mortality risk resulting from benzodiazepine/opioid interactions.

In this study of adult patients initiating hemodialysis, we sought to estimate the percentage of patients who were dispensed benzodiazepines and codispensed opioids, identify the risk factors for benzodiazepine dispensing, quantify the association between benzodiazepines and mortality, and test whether the mortality risk associated with benzodiazepines differs according to opioid codispensing. We hypothesized that these risks may differ by whether the benzodiazepines are short acting or long acting due to their differences in indications and pharmacokinetics.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

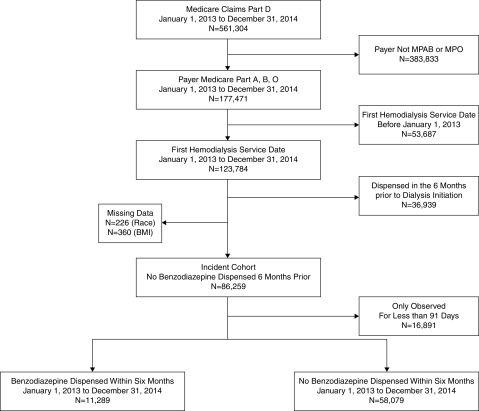

We identified 69,368 adult patients (≥18 years old) with Medicare coverage and no benzodiazepine dispensing in the 6 months prior to dialysis initiation in the US Renal Data System (USRDS), a national registry of all patients receiving treatment for kidney failure in the United States, who initiated hemodialysis (January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2014) (Figure 1). The study was limited to these years because benzodiazepines were only covered under Part D starting in 2013. The USRDS includes the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medical Evidence Report 2728 forms and is linked to Medicare claims data. During the first 90 days after dialysis initiation, patients entered the cohort (late entry) when they were enrolled in Medicare Parts A, B, and D. We ascertained patient characteristics, dialysis factors, and comorbid conditions from the Medical Evidence Report and the USRDS data as well from diagnosis codes in Medicare claims data during the time between Medicare enrollment and 90 days after enrollment. The only variables with missing data were body mass index (<1%) and race (<1%), and we performed a complete patient analysis (i.e., we dropped observations with missing information).

Figure 1.

Sixty-nine thousand, three hundred sixty-eight adults initiating hemodialysis between 2013 and 2014 were selected to be in the study sample. The dialysis initiation cohort was restricted to United States citizens aged 18 years old and older. MPAB, medicare part A and B; MPO, mediare primary, other.

As is standard with the USRDS data, mortality was augmented through linkage with the Social Security Death Master File and from the CMS data. This study was reviewed by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board, and it was determined to be exempt.

Benzodiazepine and Other Presciption Medications

We used Part D prescription claims data to ascertain if patients were dispensed a prescription for a benzodiazepine, abstracting the date that the prescriptions were filled and the days’ supply for each prescription (Supplemental Figure 1). We allowed for a 7-day gap between the end of one prescription (date that prescription was filled + days’ supply) and the fill date of the subsequent benzodiazepine prescription to account for the as needed consumption of benzodiazepines; this full episode of care was considered in the benzodiazepine exposure. There was no lag after the end of a prescription given the short-acting nature of benzodiazepines. As has been previously published (18), the short-acting benzodiazepines were defined as t1/2≤24 hours, and the long-acting benzodiazepines were defined as t1/2>24 hours (Supplemental Table 1). Furthermore, we estimated the dose of benzodiazepines by converting to lorazepam milligram equivalent (LME) by multiplying the dose for each benzodiazepine by the conversion factor. We used a similar approach for opioids, sedatives, and antipsychotics (Supplemental Table 1).

Statistical Analyses

Benzodiazepine and Opioid Codispensing.

We estimated the cumulative incidence of the first benzodiazepine dispensing using the Kaplan–Meier approach and plotted the cumulative incidences by race. Codispensing was defined as concurrent prescription fills, the most conservative approach; in other words, benzodiazepine and opioid prescriptions were filled on the same day.

We identified risk factors for the time to first dispensed benzodiazepine after hemodialysis initiation using a Cox proportional hazards models, and we censored for end of follow-up (September 1, 2015), end of Medicare coverage, change in dialysis modality, withdrawal from dialysis, kidney transplantation, or mortality; risk factors were selected on the basis of a priori hypotheses and findings from previous publications (15,16).

Benzodiazepines and Mortality.

We estimated the mortality risk associated with benzodiazepine dispensing using a Cox proportional regression model adjusting for age, sex, race, year of dialysis initiation, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, history of cancer, drug dependence, inability to ambulate, institutionalization, and smoking status. The model was censored for end of follow-up (September 1, 2015), end of Medicare coverage, change in dialysis modality, withdrawal from dialysis, kidney transplantation, or mortality. Benzodiazepine and opioids were treated as time-varying exposures. For all analyses, we compared patients with benzodiazepine/opioids with those without benzodiazepine/opioids to be consistent with previous research in patients undergoing dialysis (19). This was appropriate because the indications for benzodiazepines and opioids are broad and common in this population; furthermore, the indications are not necessarily captured through claims. However, we performed sensitivity analyses as described below. We tested whether the mortality risk associated with benzodiazepines differed by age, sex, race, and opioids (time varying) using Wald tests; we pulled the stratified associations from the Cox proportional hazards models and estimated them using the lincom command in Stata. We used separate models to quantify the association between any benzodiazepine, short-acting benzodiazepines, and long-acting benzodiazepines and mortality.

Sensitivity Analyses.

We performed a number of sensitivity analyses to test whether our results were robust to assumptions that we made. First, we tested whether changing the number of days (0, 14, and 28 days) allowed in a gap between prescriptions affected our findings. Second, we tested whether our results were robust when comparing person-time exposed to benzodiazepines (and opioids) with person-time not exposed to these medications among those who had at least one prescription for a benzodiazepine. Third, to test whether confounding by indication affected the strength of our associations, we used a propensity score matching approach on the basis of a previously published study of benzodiazepines (12). Specifically, we generated one propensity score for short-acting benzodiazepines and one for long-acting benzodiazepines among our study population of patients undergoing hemodialysis.

Statistical Methods.

We used a two-sided α of 0.05 to indicate a statistically significant difference. Proportional hazards models were confirmed visually by graphing the log-log plot of survival and statistically using Schoenfeld residuals. All analyses were performed using Stata 14.2/MP for Linux (College Station, TX).

Results

Study Characteristics

Among 69,368 patients initiating hemodialysis, the median age was 67 years old (interquartile range, 56–76), 46% were women, and 68% were white.

Benzodiazepines after Hemodialysis Initiation

Within 12 months of hemodialysis initiation, 21% (n=14,116) of patients were dispensed a benzodiazepine; 16% (n=10,854) were dispensed a prescription for a short-acting benzodiazepine by 12 months, and 5% (n=3262) were dispensed a prescription for a long-acting benzodiazepine by 12 months. Throughout follow-up, <1% of person-time (201 patients) included short- and long-acting benzodiazepine codispensing. Of all dispensed benzodiazepines, 82% were short acting, and the most frequent prescriptions were for alprazolam (36%), lorazepam (29%), clonazepam (14%), and temazepam (12%).

Risk Factors for Benzodiazepines

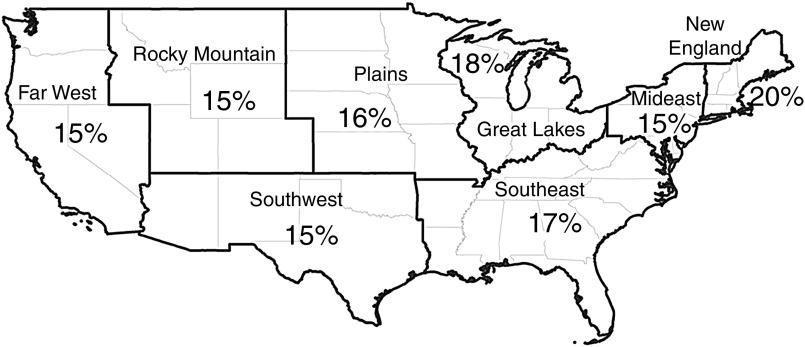

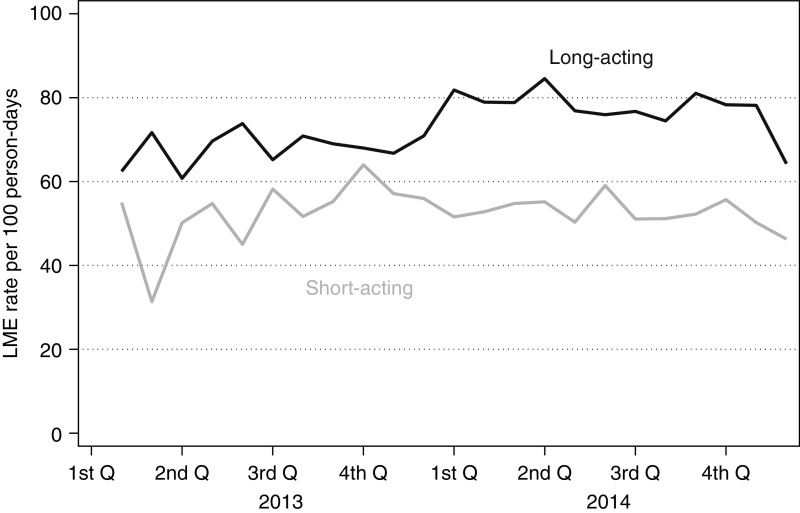

Patients who were older (median age 68 versus 67 years old), women (54% versus 44%), and white (80% versus 65%) were more likely to be dispensed a benzodiazepine within 6 months of hemodialysis initiation (Table 1). Furthermore, there were geographic differences in the percentages of patients who were dispensed benzodiazepines within 6 months of dialysis initiation, with New England having the highest burden (20%) of dispensing (Figure 2). There was little change over time in the dispensing of short- and long-acting benzodiazepines when examining the LME rate per 100 person-days (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients who initiated dialysis (n=69,368) between January 2013 and December 2014 by benzodiazepine dispensing within 6 months of initiation

| Characteristic | Benzodiazepine within 6 mo, n=11,289 | No Benzodiazepine within 6 mo, n=58,079 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr, median [IQR] | 68 [59–77] | 67 [56–76] |

| BMI, kg/m2, median [IQR] | 28 [24–34] | 28 [24–34] |

| Women, % | 54 | 44 |

| White, % | 80 | 65 |

| Dialysis initiation in 2013, % | 59 | 57 |

| Opioids, % | 76 | 56 |

| Neuropathic pain medication, % | ||

| Any | 68 | 49 |

| Gabapentin | 26 | 18 |

| Antidepressant, % | 56 | 29 |

| CNS depressant, % | 37 | 18 |

| Comorbidity, % | ||

| Diabetes | 58 | 60 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 57 | 52 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 14 | 11 |

| Hypertension | 88 | 89 |

| COPD | 16 | 10 |

| Tobacco use | 8 | 6 |

| Cancer | 8 | 7 |

| Drug use | 3 | 2 |

| Inability to ambulate | 20 | 16 |

| Institutionalized | 13 | 9 |

| No comorbidity | 1 | 2 |

| Cause of kidney failure, % | ||

| Diabetes | 47 | 49 |

| Hypertensive kidney disease | 31 | 32 |

| GN | 6 | 6 |

| Other | 16 | 13 |

| Dual eligible, % | 47 | 46 |

| Employment status, % | ||

| Unemployed | 19 | 26 |

| Full time | 1 | 2 |

| Part time | 1 | 2 |

| Retired | 46 | 42 |

| Disabled | 29 | 24 |

| Other | 3 | 4 |

Medications were ascertained at any point during follow-up. IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; CNS, central nervous system; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Figure 2.

Benzodiazepine dispensing differed by geographic region among patients inititiating hemodialysis (n=69,368) between 2013 and 2014.

Figure 3.

Benzodiazepine dispensing barely changed over time among patients inititiating hemodialysis (n=69,368) between 2013 and 2014. Rates by quarter (Q) are presented as lorazepam milligram equivalent (LME) per 100 person-days.

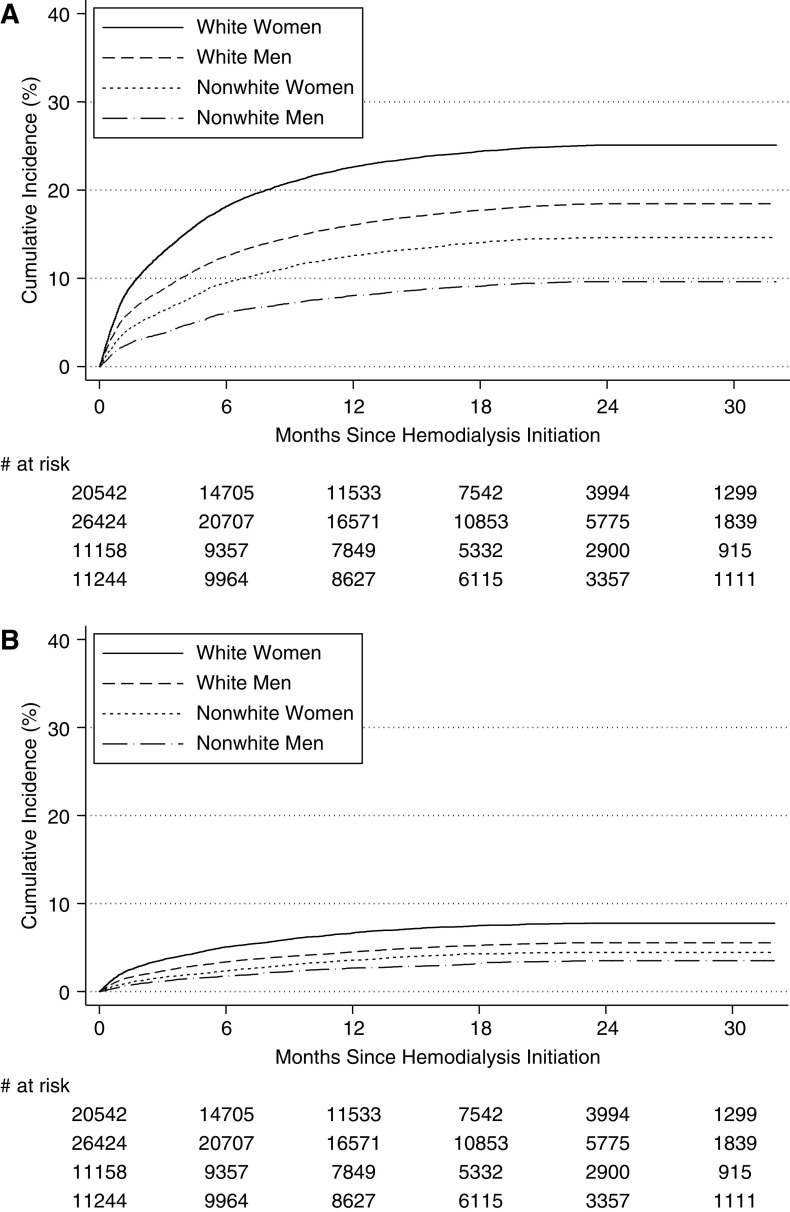

The cumulative incidence of short-acting benzodiazepines at 12 months was greater for older (age ≥65 years old) age (18% versus 14%) and women (19% versus 14%) (Supplemental Table 2); the cumulative incidence by age and sex was similar for long-acting benzodiazepine. White women were most likely to be dispensed short-acting benzodiazepines (Figure 4A) and long-acting benzodiazepines (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

The cumulative incidence of time to first short-acting benzodiazepine prescription dispensed among patients initiating hemodialysis (n=69,368) between 2013 and 2014 differed by race and sex. (A) Cumulative incidence of short-acting benzodiazepine. Approximately 18.1% of white women, 12.5% of white men, 9.5% of nonwhite women, and 6.1% of nonwhite men had used a short-acting benzodiazepine within 6 months of initiating dialysis. (B) Cumulative incidence of long-acting benzodiazepine. Approximately 5.1% of white women, 3.4% of white men, 2.3% of nonwhite women, and 1.8% of nonwhite men had used a long-acting benzodiazepine within 6 months of initiating dialysis.

After adjustment, white patients (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.73; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.66 to 1.82) and women (aHR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.27 to 1.37) were more likely to be dispensed short-acting benzodiazepines (Table 2); the risk also grew higher with age (aHR, 1.05 per 10-year older; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.07). An important difference in risk factors for long-acting benzodiazepines was that younger patients were more likely to be dispensed this medication (aHR, 0.90 per 10-year older; 95% CI, 0.87 to 0.93).

Table 2.

Factors associated with short-acting and long-acting benzodiazepines among adults initiating hemodialysis (n=69,368) between 2013 and 2014

| Factor | Benzodiazepine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short Acting | Long Acting | |||

| aHR (95% CI) | P Value | aHR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Age, per 10-yr older | 1.05 (1.03 to 1.07) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.87 to 0.93) | <0.001 |

| Women | 1.32 (1.27 to 1.37) | <0.001 | 1.35 (1.26 to 1.45) | <0.001 |

| White | 1.73 (1.65 to 1.82) | <0.001 | 1.74 (1.59 to 1.89) | <0.001 |

| Opioids | 1.66 (1.59 to 1.74) | <0.001 | 1.11 (1.03 to 1.20) | 0.01 |

| Antidepressant | 1.89 (1.81 to 1.96) | <0.001 | 1.59 (1.47 to 1.71) | <0.001 |

| CNS depressant | 1.73 (1.66 to 1.80) | <0.001 | 1.69 (1.56 to 1.82) | <0.001 |

| Year of dialysis initiation | ||||

| 2013 versus 2014 | 1.11 (1.07 to 1.16) | <0.001 | 1.30 (1.21 to 1.40) | <0.001 |

| BMI, per 10-kg/m2 higher | 0.95 (0.92 to 0.97) | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.02) | 0.24 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Diabetes | 0.92 (0.88 to 0.97) | 0.003 | 0.99 (0.90 to 1.08) | 0.76 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.10) | 0.009 | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) | 0.22 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.09) | 0.25 | 1.09 (0.98 to 1.21) | 0.13 |

| Hypertension | 0.97 (0.91 to 1.03) | 0.27 | 0.99 (0.88 to 1.12) | 0.90 |

| COPD | 1.20 (1.13 to 1.27) | <0.001 | 1.28 (1.16 to 1.43) | <0.001 |

| Tobacco use | 1.09 (1.01 to 1.17) | 0.02 | 1.19 (1.05 to 1.35) | 0.01 |

| Cancer | 1.10 (1.02 to 1.18) | 0.01 | 1.02 (0.88 to 1.17) | 0.80 |

| Drug use | 1.10 (0.97 to 1.24) | 0.14 | 1.03 (0.83 to 1.28) | 0.75 |

| Inability to ambulate | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.15) | 0.002 | 1.11 (1.00 to 1.23) | 0.06 |

| Institutionalized | 1.08 (1.01 to 1.15) | 0.03 | 0.90 (0.79 to 1.02) | 0.11 |

| No comorbidity | 0.87 (0.73 to 1.04) | 0.13 | 0.91 (0.68 to 1.23) | 0.56 |

| Cause of kidney failure | ||||

| Diabetes | Reference | Reference | ||

| Hypertensive kidney disease | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.09) | 0.15 | 1.03 (0.93 to 1.14) | 0.53 |

| GN | 1.01 (0.93 to 1.10) | 0.78 | 1.22 (1.05 to 1.42) | 0.01 |

| Other | 1.06 (0.99 to 1.13) | 0.08 | 1.20 (1.06 to 1.35) | 0.005 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Full time | Reference | Reference | ||

| Part time | 0.95 (0.76 to 1.18) | 0.64 | 1.24 (0.84 to 1.84) | 0.28 |

| Unemployed | 0.98 (0.84 to 1.14) | 0.76 | 1.31 (0.98 to 1.75) | 0.07 |

| Retired | 1.05 (0.90 to 1.23) | 0.52 | 1.38 (1.02 to 1.85) | 0.04 |

| Disabled | 1.13 (0.97 to 1.32) | 0.13 | 1.67 (1.25 to 2.24) | 0.001 |

| Other | 0.90 (0.75 to 1.08) | 0.26 | 1.22 (0.88 to 1.71) | 0.24 |

| Bureau of economic analysis regions | ||||

| Midwest | 0.89 (0.80 to 0.99) | 0.03 | 0.73 (0.60 to 0.88) | 0.003 |

| Great Lakes | 0.96 (0.86 to 1.06) | 0.40 | 0.93 (0.77 to 1.11) | 0.41 |

| Plains | 0.78 (0.69 to 0.88) | <0.001 | 0.77 (0.62 to 0.96) | 0.02 |

| Southeast | 1.03 (0.93 to 1.13) | 0.59 | 0.93 (0.78 to 1.11) | 0.42 |

| Southwest | 0.93 (0.84 to 1.04) | 0.20 | 0.74 (0.61 to 0.89) | 0.004 |

| Rocky | 0.73 (0.61 to 0.88) | 0.002 | 0.76 (0.55 to 1.04) | 0.09 |

| Far West | 0.98 (0.88 to 1.09) | 0.69 | 0.70 (0.58 to 0.85) | 0.001 |

All factors were included in a single Cox proportional hazards model with time from hemodialysis initiation to the first dispensed prescription for a short-acting or long-acting benzodiazepines as the outcome. aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Opioid Codispensing with Benzodiazepine

Among patients who were dispensed opioids, the three most commonly dispensed opioids were hydrocodone (45%; n=31,215), oxycodone (26%; n=18,035), and tramadol (12%; n=9711). Among patients who were dispensed a benzodiazepine, 30% were codispensed an opioid; 26% (n=3829) of patients with a short-acting benzodiazepine and 8% (n=1238) of those with a long-acting benzodiazepine had opioid codispensing. After adjustment, those patients with opioids compared with those without opioids were more likely to have short-acting (aHR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.59 to 1.74) and long-acting (aHR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.20) benzodiazepines dispensed (Table 2).

Benzodiazepines and Mortality

During follow-up, 15,175 deaths occurred (30%) and 1245 (2%) received kidney transplantation during a median follow-up time of 16 months (interquartile range, 8–23; minimum =7 months and maximum =33 months). Patients with a benzodiazepine were at 1.31-fold (95% CI, 1.23 to 1.40) greater mortality risk (Table 3) after adjustment. After adjustment, patients with a short-acting benzodiazepine had a higher mortality risk (aHR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.35 to 1.56), and those with a long-acting benzodiazepine were associated with a lower mortality risk (aHR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.72 to 0.99).

Table 3.

Association between benzodiazepines and mortality in patients initiating hemodialysis (n=69,368) between 2013 and 2014

| Exposure | No. of Deaths | Any, aHR (95% CI) | Short Acting, aHR (95% CI) | Long Acting, aHR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepine | 16,981 | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.52 (1.41 to 1.64) | 1.73 (1.60 to 1.88) | 0.83 (0.67 to 1.02) | |

| Adjusted | 1.31 (1.23 to 1.40) | 1.45 (1.35 to 1.56) | 0.84 (0.72 to 0.99) | |

| LME per milligram higher | 1.05 (1.03 to 1.07) | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.05) | ||

| Alprazolam (0.5 LME) | 1.33 (1.17 to 1.51) | |||

| Lorazepam (1.0 LME) | 2.06 (1.82 to 2.34) | |||

| Temazepam (10 LME) | 1.48 (1.23 to 1.80) | |||

| Clonazepam (0.25 LME) | 0.73 (0.56 to 0.94) | |||

| Diazepam (5 LME) | 1.00 (0.69 to 1.44) |

Use of benzodiazepines was treated as time varying, and all models were adjusted. The results below are from three separate models; all models were adjusted for age, sex, race, prescription (antidepressants and CNS depressants), and comorbidities. CNS depressants included sedatives, muscle relaxants, and antipsychotics. Comorbidities included diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, COPD, smoking history, cancer, drug abuse, inability to ambulate, institutionalized, and obesity. In the short-acting benzodiazepine model, those taking long-acting benzodiazepines were treated as unexposed. Similarly, in the long-acting benzodiazepine model, those taking short-acting benzodiazepines were treated as unexposed. LME, lorazepam milligram equivalent.

A 1-mg higher LME for short-acting benzodiazepines was associated with a 1.05-fold (95% CI, 1.03 to 1.07) higher mortality risk (Table 3). There was no association between dose (continuous) and mortality among long-acting benzodiazepines. When doses were converted to the relative potency of lorazepam, all doses of short-acting benzodiazepines were associated with mortality compared with no benzodiazepine. Among long-acting benzodiazepines, only 0.25 LME (clonazepam) was associated with a lower mortality risk.

The mortality risk associated with short-acting benzodiazepines differed between men and women (Pinteraction=0.006) (Supplemental Table 2). Among men, short-acting benzodiazepines were associated with a 1.62-fold (95% CI, 1.47 to 1.79) higher mortality risk. However, among women, short-acting benzodiazepines were associated with a 1.31-fold (95% CI, 1.18 to 1.44) higher risk after adjustment. This differential mortality risk by sex was not observed for long-acting benzodiazepines (Pinteraction=0.06).

Mortality and Codispensing of Benzodiazepines Opioids

Furthermore, this mortality risk differed by opioids (Pinteraction=0.001): among those with an opioid, benzodiazepines were associated with a 1.66-fold (95% CI, 1.46 to 1.90) higher mortality risk compared with those without benzodiazepines. However, among those without an opioid, benzodiazepines were associated with a 1.22-fold (95% CI, 1.13 to 1.32) higher mortality risk after adjustment compared with those without benzodiazepines (Table 4). This differential risk was limited to those with short-acting benzodiazepines (Pinteraction<0.001). Among those with opioids, short-acting benzodiazepines were associated with a 1.90-fold (95% CI, 1.65 to 2.18) higher mortality risk compared with those without short-acting benzodiazepines, whereas among those without opioids, short-acting benzodiazepines were associated with a 1.34-fold (95% CI, 1.23 to 1.45) higher risk compared with those without short-acting benzodiazepines (Pinteraction<0.001). Among long-acting benzodiazepines, the mortality risk associated with long-acting benzodiazepines did not differ by whether patients were dispensed opioids (Pinteraction=0.72).

Table 4.

Association between benzodiazepines and mortality in patients initiating hemodialysis (n=69,368) between 2013 and 2014 stratified by age, sex, race, and opioid codispensing

| Exposure | No. of Deaths | Follow-Up Time, person-yr | Unadjusted aHR (95% CI) | Adjusted aHR (95% CI) | P Value for Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any benzodiazepine | 0.001 | ||||

| No opioid/no benzodiazepine | 2556 | 182,800 | Reference | Reference | |

| No opioid/benzodiazepine | 485 | 41,273 | 1.32 (1.20 to 1.44) | 1.22 (1.13 to 1.32) | |

| Opioid/no benzodiazepine | 2071 | 141,526 | Reference | Reference | |

| Opioid/benzodiazepine | 190 | 8105 | 2.35 (2.04 to 2.71) | 1.66 (1.46 to 1.90) | |

| Short-acting benzodiazepine | <0.001 | ||||

| No opioid/no benzodiazepine | 2514 | 174,636 | Reference | Reference | |

| No opioid/benzodiazepine | 420 | 31,186 | 1.50 (1.36 to 1.65) | 1.34 (1.23 to 1.45) | |

| Opioid/no benzodiazepine | 2094 | 143,450 | Reference | Reference | |

| Opioid/benzodiazepine | 167 | 6181 | 2.74 (2.35 to 3.19) | 1.90 (1.65 to 2.18) | |

| Long-acting benzodiazepine | 0.72 | ||||

| No opioid/no benzodiazepine | 2305 | 157,870 | Reference | Reference | |

| No opioid/benzodiazepine | 67 | 10,280 | 0.74 (0.58 to 0.94) | 0.83 (0.69 to 1.00) | |

| Opioid/no benzodiazepine | 2238 | 147,590 | Reference | Reference | |

| Opioid/benzodiazepine | 23 | 2041 | 1.11 (0.74 to 1.67) | 0.89 (0.64 to 1.24) |

Use of benzodiazepines and other medications was treated as time varying, and all models were adjusted. The results below are from three separate models; all models were adjusted for age, sex, race, prescription (antidepressants and CNS depressants), and comorbidities. CNS depressants included sedatives, muscle relaxants, and antipsychotics. Comorbidities included diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, COPD, smoking history, cancer, drug abuse, inability to ambulate, institutionalized, and obesity.

Sensitivity Analyses

Similar inferences were reached when we allowed for 0-, 14-, and 28-day gaps between the end of one prescription and the fill date of a subsequent fill. For example, when there was a 0-day gap, any benzodiazepine use was associated with a 1.33-fold (95% CI, 1.23 to 1.44) higher mortality risk; the associations remained for short-acting benzodiazepine (aHR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.38 to 1.63) and long-acting benzodiazepine (aHR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62 to 0.94). Additionally, results were consistent when we (1) limited the population (n=15,238) to patients with at least one dispensed benzodiazepine prescription (short-acting benzodiazepine: aHR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.31 to 1.56; long-acting benzodiazepine: aHR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.56 to 0.85) and (2) used a propensity score matched model (short-acting benzodiazepine: aHR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.17; long-acting benzodiazepine: aHR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.86 to 0.98). Interactions between benzodiazepine and opioids were also identified (Pinteraction<0.001) in these sensitivity analyses.

Discussion

In this national study of 69,368 patients initiating hemodialysis, 16% were dispensed a short-acting acting benzodiazepine within 1 year of hemodialysis initiation, and this dispensing was more common in older patients, white patients, and women. Among patients with a short-acting benzodiazepine, 26% were also codispensed an opioid. Short-acting benzodiazepines were independently associated with a 1.9-fold higher risk of mortality among patients codispensed an opioid. In contrast, long-acting benzodiazepines were less commonly dispensed (5% within 1 year), which was associated with a lower mortality risk, and there were no differences when codispensed with opioids. Our findings of a synergistic effect of short-acting benzodiazepines and opioids are of great concern in light of the opioid epidemic.

Previous findings from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (1999–2004) suggest that 15%–19% of patients undergoing hemodialysis are treated with a benzodiazepine for depression (15). Furthermore, in a study of 3690 patients initiating hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis between 1996 and 1997 who participated in the Dialysis Morbidity and Mortality Study Wave 2, 14% were taking a benzodiazepine at 60 days after initiation on the basis of chart abstractions (16). We built on these previous findings by estimating the cumulative incidence of short-acting and long-acting benzodiazepines after hemodialysis initiation. Similar to this cohort, we found that patients who were white or women were all more likely to have a short-acting benzodiazepine prescription.

Our study was conducted among patients who initiated hemodialysis between 2013 and 2014 rather than in earlier eras (16) prior to the opioid epidemic; this allowed us to evaluate the extent of codispensing with opioids. Among patients who were dispensed a short-acting benzodiazepine, 23% filled a prescription for an opioid on the same day. To our knowledge, this is the first national study of United States patients initiating hemodialysis that estimated the extent of codispensing. Although we used the most stringent definition of codispensing (filling both an opioid prescription and a benzodiazepine prescription on the same day), we still found a staggering burden of coprescribing. It is likely that the true burden of concomitant use of these two medications is even higher.

Similar to the previous studies (15,16), our findings suggest that benzodiazepines (specifically short-acting benzodiazepines) are associated with greater mortality. Leveraging this incident hemodialysis cohort design and treating exposure as time varying, we found a stronger association (aHR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.23 to 1.40) between benzodiazepines and mortality than either of the prior studies (adjusted relative risk, 1.27 [15]; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.59, and aHR, 1.15 [16]; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.31). Furthermore, whereas the Dialysis Morbidity and Mortality Study Wave 2 studies found no association between long-acting benzodiazepines and mortality, in our study we found a lowered mortality risk even after accounting for confounders. These findings extend the previous research on psychoactive mediations and adverse outcomes in older patients on hemodialysis, which did not include benzodiazepines (20). Although we observed a higher mortality risk associated with short-acting benzodiazepines, we must interpret these findings with caution because these findings may also reflect channeling bias, residual confounding, or selection bias.

Our findings of a lower mortality risk with long-acting benzodiazepines replicate a previous finding in the general United States population (hazard ratio, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.55 to 0.65) (12). The benzodiazepine-related mortality risk may be limited to short-acting benzodiazepines due to their pharmacokinetic properties. Unlike long-acting benzodiazepines, those that are short-acting have a rapid onset, which is associated with physical dependence, symptomatic withdrawal, and subsequent misuse and addiction; this is particularly a concern with diazepam (21,22). Also, they are often typically prescribed in higher doses for treatment of insomnia. In contrast, long-acting benzodiazepines have a slower absorption and onset of action, and thy are most commonly used to treat chronic generalized anxiety disorder when a patient has minimal depressive symptoms and no substance use disorder. They are also used to treat alcohol withdrawal because they provide a steady level of symptom control owing to their t1/2 and active metabolites. Low-dose, long-acting benzodiazepines may have a more favorable risk-benefit profile because they are associated with more delayed and attenuated withdrawal symptoms; in particular, clonazepam has been found to produce less interdose anxiety (23). However, these results should be interpreted with caution because there is always the potential for channeling bias, unmeasured/unmeasurable confounders, or other forms of bias that would lead to a noncausal association.

The main strength of this study was the large sample size with real-world dispensing of short- and long-acting benzodiazepines and opioids (treated as time varying); this allowed us to identify high-risk subgroups, like those patients who were codispensed opioids. Furthermore, we leveraged a cohort of patients initiating hemodialysis to mitigate any survival bias introduced by studying prevalent patients on hemodialysis with a history of use of a benzodiazepine. The main limitations of this study, like all claims-based pharmacoepidemiology studies, are (1) that exposures were limited to dispensed prescriptions rather than a measure of actual consumption of medications, (2) that illicit use of benzodiazepines was not captured, (3) that all potential sources of medications among those with Medicare coverage may not be represented, (4) that we were unable to separate the medication effects on mortality from the effects of the underlying conditions, and (5) that there was no cause of death. Furthermore, we cannot be certain that these participants were new users of benzodiazepines even after excluding patients with dispensing within 6 months prior to dialysis initiation; however, the US Food and Drug Administration labeling and clinical guidelines suggest benzodiazepine use no longer than 8–10 weeks (24–26). For these reasons, we cannot draw causal inferences from the observed associations between benzodiazepines, opioids, and mortality.

In summary, patients initiating hemodialysis have a high burden of short-acting benzodiazepines, and 23% of these patients were codispensed opioids. Codispensing is associated with a 1.9-fold higher mortality risk. In light of the opioid epidemic, physicians caring for patients undergoing hemodialysis should check their state’s prescription drug monitoring programs to see whether their patient has been dispensed opioids before prescribing a short-acting benzodiazepine. The potential risks associated with short-acting benzodiazepines should always be weighed against their therapeutic benefit, and patients undergoing hemodialysis who are currently undergoing treatment with short-acting benzodiazepines should consider other treatments when clinically appropriate. Furthermore, providers caring for patients undergoing hemodialysis should be given the tools needed to implement a collaborative, team-based approach for deprescribing short-acting benzodiazepines, particularly for patients who are likely to use opioids. In conclusion, high-risk codispensing of short-acting benzodiazepines and opioids should be recognized and reduced by physicians caring for this vulnerable population.

Disclosures

Dr. Segev reports personal fees from Sanofi-Aventis and Novartis outside the submitted work. Dr. Bae, Dr. Chu, Dr. Daubresse, Dr. Lentine, Dr. McAdams-DeMarco, and Dr. Muzaale have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided in part by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants R01DK120518 (principal investigator [PI]: Dr. McAdams-DeMarco) and K24DK101828 (PI: Dr. Segev), and National Institute on Aging grant R01AG055781 (PI: Dr. McAdams-DeMarco).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The data reported here have been supplied by the US Renal Data System. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US Government. All data can be publicly obtained.

Dr. McAdams-DeMarco, Dr. Muzaale, and Dr. Segev designed the study; Dr. Muzaale analyzed the data; Dr. Bae, Dr. Chu, Dr. Daubresse, Dr. Lentine, Dr. McAdams-DeMarco, Dr. Muzaale, and Dr. Segev drafted and revised the manuscript; and Dr. Bae, Dr. Chu, Dr. Daubresse, Dr. Lentine, Dr. McAdams-DeMarco, Dr. Muzaale, and Dr. Segev (1) made substantial contribution to conception and design of the work, to data acquisition, to data analysis, or to data interpretation; (2) drafted or revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; (3) approved the final version of the manuscript; and (4) agree to be personally accountable for the individual’s own contributions and to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work, even one in which the author was not directly involved, are appropriately investigated and resolved, including with documentation in the literature if appropriate.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related Patient Voice, “A Patient’s Perspective on Benzodiazepines, Co-Dispensed Opioids, and Mortality among Patients Initiating Long-Term In-Center Hemodialysis,” on pages 743–744.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.13341019/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Figure 1. Illustration of time-varying exposure to benzodiazepine or opioid claims for one person.

Supplemental Table 1. List of classes and medications.

Supplemental Table 2. Association between benzodiazepines and mortality in patients initiating hemodialysis (n=69,368) between 2013 and 2014 stratified by age, sex, race, and opioid codispensing.

References

- 1.Cunningham CM, Hanley GE, Morgan S: Patterns in the use of benzodiazepines in British Columbia: Examining the impact of increasing research and guideline cautions against long-term use. Health Policy 97: 122–129, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M: Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 72: 136–142, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones CM, McAninch JK: Emergency department visits and overdose deaths from combined use of opioids and benzodiazepines. Am J Prev Med 49: 493–501, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachhuber MA, Hennessy S, Cunningham CO, Starrels JL: Increasing benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality in the United States, 1996-2013. Am J Public Health 106: 686–688, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall SA, Chiu GR, Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Link CL, Kupelian V, McKinlay JB: General exposures to prescription medications by race/ethnicity in a population-based sample: Results from the Boston Area Community Health Survey. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 19: 384–392, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen SD, Cukor D, Kimmel PL: Anxiety in patients treated with hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 2250–2255, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scherer JS, Combs SA, Brennan F: Sleep disorders, restless legs syndrome, and uremic pruritus: Diagnosis and treatment of common symptoms in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 69: 117–128, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hegde A, Veis JH, Seidman A, Khan S, Moore J Jr.: High prevalence of alcoholism in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 35: 1039–1043, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davison SN, Koncicki H, Brennan F: Pain in chronic kidney disease: A scoping review. Semin Dial 27: 188–204, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall J, Higginson IJ: The prevalence of symptoms in end-stage renal disease: A systematic review. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 14: 82–99, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kandel DB, Hu MC, Griesler P, Wall M: Increases from 2002 to 2015 in prescription opioid overdose deaths in combination with other substances. Drug Alcohol Depend 178: 501–511, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patorno E, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Lee MP, Huybrechts KF: Benzodiazepines and risk of all cause mortality in adults: Cohort study. BMJ 358: j2941, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park TW, Saitz R, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS: Benzodiazepine prescribing patterns and deaths from drug overdose among US veterans receiving opioid analgesics: Case-cohort study. BMJ 350: h2698, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R: CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA 315: 1624–1645, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuhara S, Green J, Albert J, Mihara H, Pisoni R, Yamazaki S, Akiba T, Akizawa T, Asano Y, Saito A, Port F, Held P, Kurokawa K: Symptoms of depression, prescription of benzodiazepines, and the risk of death in hemodialysis patients in Japan. Kidney Int 70: 1866–1872, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winkelmayer WC, Mehta J, Wang PS: Benzodiazepine use and mortality of incident dialysis patients in the United States. Kidney Int 72: 1388–1393, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daubresse M, Alexander GC, Crews DC, Segev DL, McAdams-DeMarco MA: Trends in opioid prescribing among hemodialysis patients, 2007-2014. Am J Nephrol 49: 20–31, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agarwal SD, Landon BE: Patterns in outpatient benzodiazepine prescribing in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2: e187399, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimmel PL, Fwu CW, Abbott KC, Eggers AW, Kline PP, Eggers PW: Opioid prescription, morbidity, and mortality in United States dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 3658–3670, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishida JH, McCulloch CE, Steinman MA, Grimes BA, Johansen KL: Psychoactive medications and adverse outcomes among older adults receiving hemodialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 67: 449–454, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffiths RR, Johnson MW: Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: A conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds. J Clin Psychiatry 66[Suppl 9]: 31–41, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffiths RR, Weerts EM: Benzodiazepine self-administration in humans and laboratory animals—implications for problems of long-term use and abuse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 134: 1–37, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herman JB, Rosenbaum JF, Brotman AW: The alprazolam to clonazepam switch for the treatment of panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 7: 175–178, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel G, Fancher TL: In the clinic. Generalized anxiety disorder. Ann Intern Med 159: ITC6-1–ITC6-11, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davidson JR: Major depressive disorder treatment guidelines in America and Europe. J Clin Psychiatry 71[Suppl E1]: e04, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein MB, Craske MG: Treating anxiety in 2017: Optimizing care to improve outcomes. JAMA 318: 235–236, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.