Abstract

Context

The first case of the new coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2), was identified in Wuhan, China, in late 2019. Since then, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak was reclassified as a pandemic, and health systems around the world have faced an unprecedented challenge.

Objective

To summarize guidelines and recommendations on the urology standard of care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Evidence acquisition

Guidelines and recommendations published between November 2019 and April 17, 2020 were retrieved using MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL. This was supplemented by searching the web pages of international urology societies. Our inclusion criteria were guidelines, recommendations, or best practice statements by international urology organizations and reference centers about urological care in different phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement. Of 366 titles identified, 15 guidelines met our criteria.

Evidence synthesis

Of the 15 guidelines, 14 addressed emergency situations and 12 reported on assessment of elective uro-oncology procedures. There was consensus on postponing radical prostatectomy except for high-risk prostate cancer, and delaying treatment for low-grade bladder cancer, small renal masses up to T2, and stage I seminoma. According to nine guidelines that addressed endourology, obstructed or infected kidneys should be decompressed, whereas nonobstructing stones and stent removal should be rescheduled. Five guidelines/recommendations discussed laparoscopic and robotic surgery, while the remaining recommendations focused on outpatient procedures and consultations. All recommendations represented expert opinions, with three specifically endorsed by professional societies. Only the European Association of Urology guidelines provided evidence-based levels of evidence (mostly level 3 evidence).

Conclusions

To make informed decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic, there are multiple national and international guidelines and recommendations for urologists to prioritize the provision of care. Differences among the guidelines were minimal.

Patient summary

We performed a systematic review of published recommendations on urological practice during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which provide guidance on prioritizing the timing for different types of urological care.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Urogenital system, Urological surgical procedures, Urology, Guidelines, Clinical decision making

Take Home Message

We performed a systematic review of published recommendations on urological practice during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which provides guidance on prioritizing the timing for different types of urological care.

1. Introduction

During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, international efforts have been made to inform and prepare health care workers in order to optimize and redirect resources and personnel to manage this crisis. As of May 4, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported 239 604 deaths [1]. To date, there is no approved vaccine for COVID-19, and the number of cases has continued to rise as of the date of submission.

Several urology societies and reference centers have published recommendations to inform urology care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is essential for urologists to prioritize patient safety, and to balance potential delays in diagnosis and treatment of urological conditions against risks of COVID-19 exposure and additional stress on health care resources. These issues are of particular concern in epicenters or areas with the greatest number of cases.

The aim of this systematic review is to summarize published guidelines and recommendations on urological care during the COVID-19 pandemic from major professional urology societies and reference centers.

2. Evidence acquisition

2.1. Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed using a combination of keywords (MeSH terms and free text words) including (“COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “Coronavirus” OR “coronavirus infections”) AND (“Urology” OR “Urogenital system”). MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL were searched (Supplementary material). The search was supplemented to include references from the pertinent articles as well as hand searches of additional relevant records on COVID-19 resource websites from the European Association of Urology (EAU), American Urological Association (AUA), and British Journal of Urology International. Our search was up-to-dated to include publications through April 17, 2020.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Articles were eligible for inclusion if they contained original guidelines or recommendations on urology standards of care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.3. Information sources

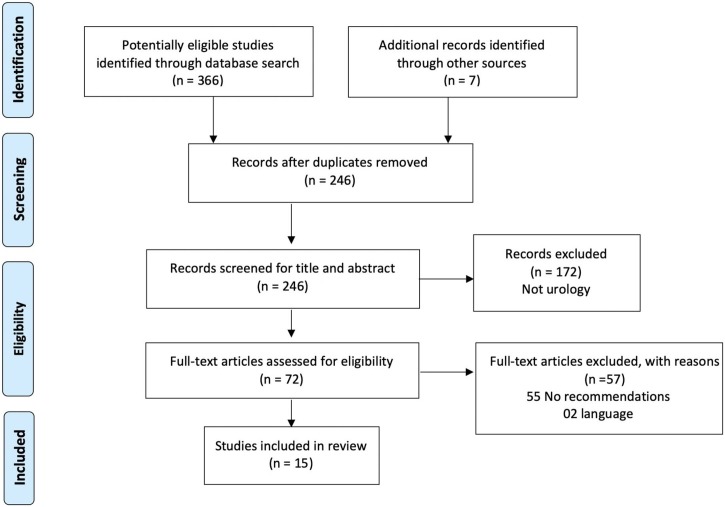

Our search strategy yielded 366 articles. All the articles were combined into EndNote reference management software, and 127 duplicates were removed. Two authors (M.L.W. and F.L.H.) independently identified and reviewed the titles and abstracts. For an article to be excluded, both reviewers had to agree that the study was not relevant. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) not focused on urology, (2) not containing recommendations involving urology practice during COVID-19, and (3) not written in English. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 72 papers were identified as potentially eligible for inclusion. After a full-text review, 15 were deemed eligible and were included. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart summarizing the results of the literature search. PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses.

2.4. Data extraction

Two independent reviewers (F.S.L. and F.L.H.) extracted all relevant recommendations from each guideline. Disagreements concerning data extraction were resolved by discussion and consensus. Thereafter, a recommendation matrix was constructed considering distinct conditions, such as urological oncology, endourology, outpatient procedures, other benign procedures, emergencies, and transplantation. The following variables were extracted from the articles: list of authors, title of the article, publication date, country, search strategy, purpose of the guideline, guideline type, subareas covered, and conclusions.

3. Evidence synthesis

For quality assessment, the team checked for the level of evidence and grade of recommendations.

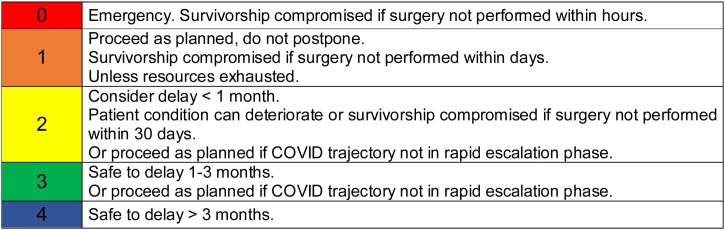

The authors summarized the recommendations using a triage grading system based on two factors: (1) possible impairment in patient condition or survivorship if surgery is not performed and (2) different regional health care resource settings (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Proposed emergency and elective procedures triage color codes to summarize collated evidence, integrating survival and healthcare resources.

Published data were used for this systematic review; hence, no ethical approval was sought.

4. Results

4.1. Study selection and characteristics of the included guidelines

All 15 included articles were accepted for publication between March 15 and April 17, 2020. The articles came from various institutions in Europe (Italy, UK, Belgium, and Switzerland), the Americas (USA, Canada, and Brazil), and Australia/New Zealand. All the 15 guidelines were based on expert opinion (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

List of included articles.

| Author(s)/title/journal | Date Month, day (2020) |

Situation reported |

Objective | Subareas | Methods | Topics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Total confirmed cases/total deaths |

Country Total confirmed cases Total deaths (new deaths in 24 h) |

||||||

| Ficarra et al [2]/Urology practice during COVID-19 pandemic/Minerva Urol Nefrol | March 23 | 332 930/14 509 | 59 138 cases 5476 (649) deaths Italy |

To summarize the procedures that should be performed in urgent, nonurgent, postponed conditions for the corresponding urological disorder | Uro-oncology, endourology, outpatients, benign conditions, emergencies | Expert opinion | Urgencies, bladder, prostate, testicular, penile, cystoscopy |

| Stensland et al [13]/Considerations in the triage of urologic surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic/Eur Urol | March 25 | 413 467/18 433 | 69 176 cases 6820 (743) deaths Italy 8081 cases 422 (87) deaths UK |

To recommend surgeries and rationality to delay or treat | Uro-oncology, endourology, outpatients, benign conditions, emergencies | Expert opinion | General |

| Mottrie et al [10]/ERUS (EAU Robotic Urology Section) guidelines during COVID-19 emergency/Eur Urol | March 25 | 413 467/18 433 | 220 516 cases 11 986 (1797) deaths Europe |

Recommendations, based on the most recent scientific pieces of evidence, to safeguard the health of health care workers and their patients, in the context of robotic surgery | Uro-oncology (robotics) | Guidelines | Urothelial cancer, prostate, renal mass, testicular, functional, reconstructive |

| USANZ [3]/Guidelines for urological prioritisation during COVID-19 | March 25 | 413 467/18 433 | 2252 Cases 8 (1) deaths Australia 189 cases 0 (0) death New Zealand |

Guidelines for surgical prioritization | Uro-oncology, endourology, outpatients, benign conditions, emergencies | Society guidelines | Uro-oncology, urgencies, endourology, outpatients |

| Katz et al [8]/Triaging office-based urology procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic/J Urol | March 25 | 413 467/18 433 | 51 914 cases 673 (202) deaths USA |

Representing a collection of urologists from several institutions across 45 countries, with expertise in different subspecialty fields of urology—seek to provide 46 frameworks to help triage office-based procedures | Uro-oncology, endourology, outpatients, benign conditions, emergencies | Expert opinion | Cystoscopy, prostate biopsies, ureteral stent removal, urodynamics, female urology |

| Kutikov et al [6] /A war on two fronts: cancer care in the time of COVID-19/Ann Intern Med |

March 27 | 509 164/23 335 | 68 334 cases 991 (107) deaths USA |

Guidance on decisions about immediate cancer treatment | Uro-oncology | Expert opinion | Urothelial cancer, prostate, renal mass, testicular |

| Goldman and Haber [4]/Recommendations for tiered stratification of urologic surgery urgency in the COVID-19 era/J Urol | March 30 | 693 282/33 106 | 122 653 cases 2112 (444) deaths USA |

Recommended surgical priority tiers | Uro-oncology, endourology, outpatients, benign conditions, emergencies | Expert opinion | Diagnostic cystoscopy, surveillance cystoscopy, intravesical instillations for bladder cancer, prostate biopsies and administration of androgen deprivation, cystoscopy with ureteral stent removal, Foley and suprapubic catheter exchanges, urodynamics |

| Ahmed et al [14]/Global challenges to urology practice during COVID-19 pandemic/BJU Int | April 3 | 972 303/50 321 | 38 700 cases 2910 (389) deaths UK |

Putting together a collection of the latest BJUI-published articles on the topic. Adapted from RCS Intercollegiate General Surgery Guidance |

Uro-oncology, endourology, outpatients, benign conditions, emergencies | Expert opinion | Outpatients, general safety |

| Lalani et al [15]/Prioritizing systemic therapies for genitourinary malignancies: Canadian recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic/Can Urol Assoc J | April 5 | 1 133 758/62 784 | 12 938 Cases 214 (62) deaths Canada |

18 academic genitourinary medical oncologists from 11 cancer centers across Canada participated in preparing this guidance document for managing patients during the current pandemic | Uro-oncology | Expert opinion | Urothelial cancer, prostate, renal mass, testicular |

| Carneiro et al [7]/Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the urologist’s clinical practice in Brazil: a management guideline proposal for low- and middle-income countries during the crisis period/Int Braz J Urol | April 9 | 1 436 198/85 521 | 13 717 cases 667 (114) deaths Brazil |

Providing suggestions and recommendations for the management of urological conditions in times of COVID-19 crisis in Brazil and other low- and middle-income countries | Uro-oncology, endourology, outpatients, benign conditions, emergencies | Expert opinion | Urolithiasis, BPH, hematuria, urgencies, urodynamic, prostate biopsy, intravesical instillations, urothelial cancer, prostate, renal mass, testicular |

| Quaedackers et al [16]/Clinical and surgical consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with pediatric urological problems: statement of the EAU Guidelines Panel for Paediatric Urology/J Pediatr Urol | April 9 | 1 436 198/85 521 | 759 661 cases 61 516 (3877) deaths Europe |

Statement with recommendations for pediatric urological cases based on published studies as well as expert opinion of the pediatric urology guidelines panel of the EAU | Pediatric urology | Society guidelines | Pediatric urology |

| Proietti et al [17]/Endourological stone management in the era of the COVID-19/Eur Urol | April 14 | 1 844 863/117 021 | 159 516 Cases 20 465 (564) deaths Italy |

Prioritization scheme for stone patients scheduled for surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic | Endourology | Expert opinion | Urolithiasis |

| Gillessen et al [18]/Advice regarding systemic therapy in patients with urological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic/Eur Urol | April 17 | 2 074 529/139 378 | 26 651 cases 1016 (43) deaths Switzerland 103 097 cases 13 729 (861) UK |

Providing treatment guidelines as a pragmatic perspective on the risk/benefit ratio | Uro-oncology | Expert opinion | Urothelial cancer, prostate, renal mass, testicular |

| Ribal et al [5]/EAU Guidelines Office-Rapid-Reaction-Group. An organization wide collaborative effort to adapt the EAU guidelines recommendations to the COVID-19 era | April 17 | 2 074 529/139 378 | 1 050 871 cases 93 480 (4163) deaths Europe |

Treatment guidelines with most levels of evidence using a 4-level priority | Uro-oncology, endourology, outpatients, benign conditions, emergencies | Society guidelines | Urothelial cancer, prostate, renal mass, testicular |

| Metzler et al [9]/Stone care triage during COVID-19 at the University of Washington/J Endourol | April 17 | 2 074 529/139 378 | 632 781 Cases 28 221 (2350) deaths USA |

Categorizing patients into five groups of priority | Endourology | Expert opinion | Urolithiasis |

BPH = benign prostatic hyperplasia; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; EAU = European Association of Urology; USANZ = Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand.

4.2. Uro-oncology

Postponing treatments for low- and intermediary-risk prostate cancer (PCa) was widely proposed as it is unlikely to result in clinical harm. Concerning high-risk PCa, some authors disagree upon postponement of surgery, while the others recommended proceeding with radical prostatectomy [2], [3]. Goldman and Haber [4] stated that surgery can be delayed beyond 3 mo, and Ribal et al [5] and Kutikov et al [6] recommended treatment before the end of 3 mo. Indeed, considering the EAU guideline, depending on the local situation of the pandemic, surgery for high-risk PCa can be postponed until after the pandemic [5]. Prescribing neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy in this situation is an option [5], [6], [7]. In the case of muscle-invasive bladder cancer, several authors stated that radical cystectomy is nondeferrable and neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be omitted [5,6,8,]. Carneiro et al [7] suggested that neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be delayed for up to 6–8 wk and cystectomy can be delayed for up to 10 wk. The authors agreed that a delay of <3 mo is acceptable for T1b-T2 renal tumors. Another concern is metastatic renal cell carcinoma. The EAU panel discussed that cytoreductive surgery is controversial irrespective of the pandemic [5]. Only two articles covered recommendations regarding adrenal masses, and both agreed that adrenal masses >4 cm or functional should be treated in <1 mo [4,8]. Orchiectomy for suspected testicular tumors is nondeferrable. While several authors suggested starting adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy for stage I seminomas, the EAU guidelines recommended active surveillance as the first choice of management for stage I seminoma [5]. Finally, concerning penile cancer, due to the lack of objective response and immunodeficiency from chemotherapy, palliative treatments and supportive care are recommended for metastatic penile cancer during the pandemic [5]. The synthesis of recommendations for uro-oncology is provided in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Summary of guidelines: urologic oncology during COVID-19 pandemic.

| Prostate cancer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/recommendation |

Surgery |

Radiation |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cancer risk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Low | Intermediate | High | High risk | Metastatic hormone sensitive | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ficarra et al [2] | Nondeferrable | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stensland et al [13] | Safe delay 12 mo | Safe delay 12 mo | If patient is ineligible for radiation | Consider radiation (for intermediary risk = safe delay 12 mo) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mottrie [10] | To postpone | High | Medium | Weak | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| USANZ [3] | Active surveillance | Initial ADT + deferred definitive treatment | As planned | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Katz et al [8] | Delay 6-8 weeks | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kutikov et al [6] | <50 yr | Safe delay >3 mo | Safe delay >3 mo | Proceed w/ immediate treatment. Delay <3 mo acceptable | Consider starting androgen deprivation if significant delay | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 50–70 yr | Balance risk and benefits of immediate treatment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| >70 yr | Consider starting androgen deprivation if significant delay | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Goldman and Haber [4] | Can be delayed beyond 12 wk | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ahmed et al [14] | As planned | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lalani et al [15] | Can be delayed up to 6 mo | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carneiro et al [7] | Postpone | Consider starting androgen deprivation | Consider starting androgen deprivation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gillessen et al [18] | Commence where possible | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ribal et al [5] | Postpone treatment for 6-12 mo Active surveillance defer by 6 mo |

Surgery can be postponed until after pandemic | Treat before end of 3 mo or can be postponed until after pandemic If patient anxious or N1, consider ADT + EBRT as alternative |

Treat before end of 3 mo (use immediate neoadjuvant ADT up to 6 mo followed by EBRT) | Offer immediate systemic treatment to M1 If low volume and planned ADT + EBRT, postpone EBRT until pandemic is no longer a major threat |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Age/recommendation | Bladder cancer | Upper tract U cancer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Low grade | Refractory CIS | Suspected > cT1 | High-grade non–muscle invasive | Muscle invasive | Multimodality bladder sparing | Metastatic first-line treatment | Presume low-risk (ureteroscopy or surgery) | High-grade nephroureterectomy | Metastatic first-line treatment | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Ficarra et al [2] | Nondeferrable | Nondeferrable | Nondeferrable | Nondeferrable | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stensland et al [13] | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | Proceed w/ immediate treatment regardless of the receipt of neoadjuvant chemo | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mottrie [10] | To postpone | Medium | Weak | Weak | Weak | Medium | Weak | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| USANZ [3] | As planned | As planned | As planned | As planned | Consider neoadjuvant chemo | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kutikov et al [6] | <70 yr | Safe delay >3 mo | Proceed w/ treatment. Delay <3 mo acceptable | Proceed w/ treatment. Delay <3 mo acceptable | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| >70 yr | Safe delay >3 mo | Balance risk and benefits of immediate treatment | Balance risk and benefits of immediate treatment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Goldman and Haber [4] | Delayed 4–12 wk | Schedule | Schedule | Delayed beyond 4-12 wk | Schedule | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ahmed et al [14] | Priority | Priority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lalani et al [15] | As planned | Adjuvant delay | Adjuvant delay whenever possible | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carneiro et al [7] | Delay | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | Neoadjuvant chemo can be delayed for up to 6–8 wk, cystectomy delay for up 10 wk | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gillessen et al [18] | Commenced where possible | Commenced where possible | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ribal et al [5] | Defer by 6 mo | Treat before end of 3 mo | Treat within <6 wk | Treat within <6 wk | Treat before end of 3 mo (consider omitting neoadjuvant chemo in T2/T3) | Treat before end of 3 mo If palliative (consider only radio + chemo) |

Treat within <6 wk Chemo adjuvant for N+ |

Not recommended to postpone >3 mo | Treat within <6 wk | Treat before end of 3 mo | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Age/ recommendation |

Kidney cancer | Adrenal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SRM <4 cm | T1b-T2 | T3 | Metastatic intermediate and poor risk | CA suspected/symptomatic | CA not suspected | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ficarra et al [2] | Nondeferrable in selective cases | Nondeferrable | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stensland et al [13] | Delay <3 mo acceptable or other forms of ablative approaches | Delay <3 mo acceptable | Proceed w/ treatment | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gillessen et al [18] | Commenced where possible | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mottrie [10] | To postpone | Medium | Medium | Weak | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| USANZ [3] | >7 cm = as planned | As planned | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kutikov et al [6] | <50 yr | Safe delay >3 mo | Proceed w/ immediate treatment. Delay <3 mo acceptable | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 50–70 yr | Safe delay >3 mo | proceed w/ immediate treatment. Delay <3 mo acceptable | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| >70 yr | Safe delay >3 mo | Balance risk and benefits of immediate treatment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Goldman and Haber [4] | Can be delayed beyond 12 wk | Can be delayed 4–12 wk | Scheduled | Can be delayed up to 4 wk | Can be delayed beyond 12 wk | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ahmed et al [14] | Priority | Priority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lalani et al [15] | Recommended | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carneiro et al [7] | Delay | Avoid delay | Proceed w/ treatment | Proceed w/ treatment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ribal et al [5] | Defer by 6 mo | Treat before end of 3 mo | Treat within <6 wk | Treat within <6 wk Consider starting on VEGFR TKI rather than immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy Cytoreductive for asymptomatic is controversial irrespective of the pandemic |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Testicular cancer | Penile cancer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orchiectomy | Postchemo RPLND | Metastatic | Local | Metastatic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stage 1 seminoma | Stage ≥ IIB seminoma or NSGCT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ficarra et al [2] | Nondeferrable | Nondeferrable | Nondeferrable | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stensland et al [13] | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | Favor chemotherapy or radiation | Chemotherapy use should be balanced by concern for immunosuppression | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| USANZ [3] | As planned | Consider deferral if suggestive of slowly growing mature teratoma | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kutikov et al [6] | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Goldman and Haber [4] | Schedule | Can be delayed up to 4 wk | Schedule | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lalani et al [15] | Minimum delay if possible | Not to initiate adjuvant chemotherapy | (Stage II seminoma or good-risk GCT with COVID-19 diagnosis) discuss chemotherapy delay whenever possible | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carneiro et al [7] | As soon as possible | Radiotherapy whenever possible (stage 2 low-volume seminoma) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gillessen et al [18] | Curative intent commenced where possible | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ribal et al [5] | May be postponed 2–3 d | Treat within <6 wk | Active surveillance is the first choice of management | Treat within <24 h | Treat within <6 wk | Consider palliation instead | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; CA = cancer; chemo = chemotherapy; CIS = carcinoma in situ; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; EBRT = external beam radiation therapy; GCT = germ cell tumor; NSGCT = nonseminomatous GCT; RPLND = retroperitoneal lymph node dissection; SRM = small renal mass; TKI = tyrosine kinase inhibitor; U = urothelial, USANZ = Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand; VEGFR = vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; w/ = with.

4.3. Endourology

Nine of the included guidelines (60%) contained recommendations related to endourology procedures. Obstructed or infected renal and ureteral stones should be considered emergencies, and decompression should be performed. However, there is a consensus that treatment of nonobstructed renal stones can be delayed for months. Nevertheless, it is important to note that patients with symptomatic ureteral/renal stone and those with pre-existing stent should be considered priorities. However, authors disagreed on the maximum waiting time ranging from 6–8 to 12 wk [4], [5], [9]. A comparison of endourology recommendations between guidelines is displayed in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Summary of guidelines: endourology (urolithiasis) procedures during COVID-19 pandemic.

| Nonobstructing renal stone | Nonobstructing ureteral stone | Renal colic | Stent removal | Stone with stent/nephrostomy tube or symptomatic | Obstructed kidney/infection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ficarra et al [2] | Postpone up to 6 mo | Emergency | ||||

| Stensland et al [13] | up to 6–12 mo | Emergency | Emergency | |||

| USANZ [3] | Delay | Delay | As planned | As planned | As planned | |

| Katz et al [8] | Without delay | Consider no delay | ||||

| Goldman and Haber [4] | Can be delayed beyond 12 wk | Schedule | Can be delayed up to 4 wk | Can be delayed 4–12 wk | Emergency | |

| Ahmed et al [14] | Urgent | |||||

| Carneiro et al [7] | Managed clinically | Delay | Not to delay | Emergency | ||

| Proietti et al [17] | Delay | Delay | Managed conservatively | Delay | Delay but consider priorities | Not to delay = only decompression |

| Metzler et al [9] | Postpone | <2–4 wk | <2–4 w (if recurrent ED visits) | <4–8 wk | Emergency | |

| Ribal et al [5] | Clinical harm very unlikely if postponed >6 mo | Clinical harm possible if postponed 3–4 mo, but unlikely | Pain relief Avoid NSAIDs (ibuprofen) when possible |

Clinical harm very unlikely if postponed >6 mo (as soon situation allows) | Clinical harm very likely if postponed >6 wk | Urgent decompression of the collecting system (PCN or stent) |

| Summary | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

ED = emergency department; NSAID = nonsteriodal anti-inflammatory drug; PCN = percutaneous nephrostomy; USANZ = Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand.

4.4. Laparoscopy and robotics

Five of the 15 guidelines (30%) included recommendations for laparoscopic/robotic surgeries (Table 4 ). Some recommendations were made about the surgical technique and surgical team, such as lower electrocautery power settings to generate less smoke that could potentially transport the virus. Moreover, urologists can consider using lower pressure on insufflation system with integrated active smoke evacuation mode. In addition, presence in the operating room should be restricted to essential staff and the operating room team must wear full personal protective equipment.

Table 4.

Summary of guidelines: robotic procedures during COVID-19 pandemic.

| Operation technique | Pneumoperitoneum disinflation | Surgical technique | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mottrie [10] | Lower electrocautery power setting | Use of system with integrated active smoke evacuation mode | Minimum number of OR staff members Fellows temporarily suspended Adopt adequate PPE |

| Ahmed et al [14] | Safety undetermined | Positive pressurization off | |

| Quaedackers et al [16] | Use suction devices as much as possible | Keep intraperitoneal pressure as low as possible and aspirate the inflated CO2 | |

| Carneiro et al [7] | Pressure as low as possible + use filter | Positive pressurization off Adopt adequate PPE |

|

| Ribal et al [5] | Electrosurgery units to the lowest settings Avoid or reduce use of monopolar electrosurgery, ultrasonic dissectors, and advanced bipolar |

Keep intraperitoneal pressure as low as possible and aspirate the inflated CO2 as much as possible before removing the trocars | All nonessential staff should stay outside Surfaces should be decontamination with chlorine (5000–10 000 mg/l; note that chlorhexidine is ineffective against COVID-19 and is not appropriate) |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; OR = operating room; PPE = personal protective equipment.

4.5. Outpatient procedures (urological oncology, neurourology, female urology, and pediatric urology)

Recommendations for ambulatory procedures are presented in Table 5 . Not all experts recommended cystoscopy for immediate investigation of macroscopic hematuria, and a delay of 1–2 mo was recommended [5]. Postponing prostate biopsy was not a consensus, and a case-by-case consideration should guide these decisions. Indeed, the Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand (USANZ) stated that Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PIRADS) 4/5 should be managed as planned; EAU suggested that there should not be a delay of >6 wk for symptomatic patients [3], [5]. Stage 2 neuromodulation should be carried on due to the possibility of infection. Authors disagreed on the timing of treating mesh complications and fistula repair. Most pediatric urology surgeries can be postponed, except for some oncological conditions or those that may lead to loss of renal function.

Table 5.

Summary of guidelines: outpatient procedures during COVID-19 pandemic (urologic oncology, neurourology, female urology, and pediatric urology).

| Uro-oncology |

Neurourology |

Female urology |

Pediatric urology |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder CA |

Prostate biopsy | Neurogenic cysto/Botox | Urodynamics | Stage 2 sacral neuromodulation | Urethral diverticula/mesh removal/sling incision/fistula | Slings, pelvic organ prolapse, sacral, pessary cleaning/exchange neuromodulation stage 1, artificial urethral sphincter | Pediatric: pyeloplasty with severe symptoms, posterior urethral valves. obstructed megaureter with loss of function, urolithiasis with recurring febrile infections | Reimplant, penile and benign testicular cases and buried penis, living donor renal tx | ||||||

| Surveillance cystoscopy |

Intravesical BCG/chemotherapy induction or postoperative |

Intravesical BCG/chemotherapy maintenance |

||||||||||||

| Low or intermediate risk | High risk | Low or intermediate risk | High risk | Low or intermediate risk | High risk | |||||||||

| Ficarra et al [2] | Postpone | Do not postpone | Postpone | |||||||||||

| Stensland et al [13] | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | Delay | Delay | |||||||||||

| Mottrie [10] | ||||||||||||||

| USANZ [3] | PIRADS 4/5 = as planned | |||||||||||||

| Katz et al [8] | Safe delay 3–6 mo | Proceed w/ immediate investigation | Patients should be prioritized for treatment | Delay indefinitely | Stop and re-evaluate in 3 mo | Safe delay 3 mo, suggest transperineal Safe delay 3–6 mo (if low or intermediate PCa suspected) |

Delay for 3–6 mo GU tract dysfunction | Without delay | Delay 3–6 mo | |||||

| Goldman and Haber [4] | PSA >15 = can be delayed 4–12 wk | Neurogenic = can be delayed up to 4 wk | Can be delayed 4–12 wk | Schedule | Can be delayed 4–12 wk | Can be delayed beyond 12 wk | Can be delayed beyond 12 wk | |||||||

| Carneiro et al [7] | Postpone | Treat as planned | Treat as planned | Postpone, suggestion under local | Delay | |||||||||

| Quaedackers et al [16] | As planned | Postpone | ||||||||||||

| Ribal et al [5] | Defer by 6 mo | Follow-up before end of 3 mo | May be abandoned | Treat within <6 wk | May be abandoned | Treat within <6 wk | Postponed until the end of the pandemic (at least as long as the confinement is ongoing) Diagnose within <6 wk (biopsy without MRI if locally advanced or highly symptomatic) |

Deferred | Clinical harm very likely if postponed >6 wk | Clinical harm very unlikely if postponed 6 mo | Clinical harm very likely if postponed >6 wk | Defer by 6 mo Reimplant (<3 mo) |

||

| Summary | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

BCG = bacillus Calmette-Guerin; CA = cancer; cysto = cystoscopy; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; PCa = prostate cancer; PIRADS = Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; tx = transplant, USANZ = Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand; w/ = with.

4.6. Kidney transplantation, infections, trauma, low urinary tract obstruction, and andrology

All but one guideline provided recommendations for managing emergencies, which were grouped into infections, trauma/hemorrhage, benign prostatic hyperplasia and urethral stricture, transplantation, and andrology (Table 6 ). With respect to renal transplantation the EAU proposed that this be postponed for >3 mo [5].

Table 6.

Summary of guidelines: procedures of other subdisciplines during COVID-19 pandemic (transplantation, infections, trauma, low urinary tract obstruction, and andrology).

| Transplantation |

Infection | Trauma | Hemorrhage |

BPH |

Urethra | Andrology |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadaveric renal tx | Living donor renal tx | Urological abscess/wound washout | surgical bleeding/trauma | Hematuria—macro (cystoscopy for) | Clot retention | Urinary retention unable to place catheter | BPH on self-catheterization or safe voiding | Urethral stricture with imminent obstruction | Penile fracture | Priapism | Infected prosthesis/devices (include artificial sphincter and penile implants) | Acute torsion | Penile prosthesis, infertility/non--CA scrotal surgery, vasectomy/circumcision, buried penis, Peyronies | |

| Ficarra et al [2] | Emergency | Emergency | Emergency | Emergency | Emergency | Emergency | Emergency | |||||||

| Stensland et al [13] | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | Delay | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | Emergency | Emergency | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | Delay | Proceed w/ suprapubic tube | Emergency | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | Proceed w/ immediate treatment | Delay | ||

| Mottrie [10] | Urgency | Urgency | ||||||||||||

| USANZ [3] | As planned | Delay of 1–2 mo | TURP only if not suitable for self-catheterization or indwelling catheter | As planned | ||||||||||

| Katz et al [8] | Without delay | |||||||||||||

| Goldman and Haber [4] | Emergency | Can be delayed beyond 12 wk | Emergency | Emergency | Emergency | Emergency | Emergency | Can be delayed beyond 12 wk | Schedule | Emergency | Emergency | Emergency | Emergency | Can be delayed beyond 12 wk |

| Ahmed et al [14] | Urgent | As planned | Urgent | |||||||||||

| Carneiro et al [7] | Emergency | Emergency | Emergency | Emergency | Emergency | Postpone | Postpone | Emergency | ||||||

| Ribal et al [5] | Clinical harm possible if postponed 3–4 mo but unlikely (case-by-case discussion) | Clinical harm very unlikely if postponed 6 mo | Life-threatening situation | Life-threatening situation | Diagnose within <6 wk | Diagnose within <24 h | Clinical harm very unlikely if postponed 6 mo | Clinical harm very likely if postponed >6 wk | Treat within <24 h | Clinical harm possible if postponed 3–4 mo but unlikely | ||||

| Summary | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

BPH = benign prostatic hyperplasia; CA = cancer; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; TURP = transurethral resection of the prostate; tx = transplant; USANZ = Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand; w/ = with.

5. Discussion

This systematic review aimed to synthesize available recommendations on risk/benefit ratio of delaying versus proceeding with the most commonly performed diagnostics and surgeries in urology during the COVID-19 crisis.

Redirection of resources and the prioritization of medical care aims to allow continuity of appropriate and timely assessment and management for patients with high-risk conditions, while minimizing undue risk and strain from conditions for which care can be delayed safely. In this regard, feasibility of the health care infrastructure should be determined according to the availability of health system resources, such as intensive care unit (ICU) beds, ventilators, personal protective equipment, COVID-19 tests, and health care professionals. The use of good surgical judgment can reduce the burden on health care systems across the globe. Nonoperative management should be considered whenever it is clinically appropriate for the patient. These decisions can also help limit team staffing and optimize local health care capacity to respond to the crisis.

Our systematic review of 15 clinical practice guidelines and recommendations across major urology subareas, and most routine conditions identified 761 separate recommendations for best urological practice during the COVID-19 crisis. The lack of standardization and differences among guidelines may result in skepticism about how to match resources with patient need. Some of this variation may be due to the date of publication amid the rapidly evolving case numbers and different available resources across different geographic areas.

Three of 15 (20%) guidelines have been endorsed by a specific panel or society: EAU, EAU Robotic Urology Section (ERUS), and USANZ [3], [5], [10].

In this review, we noted a paucity of recommendations on management of urological conditions with a more prolonged crisis. Only one guideline stated that recommendations should be revised if the crisis had a duration of ≥3 mo [7]. The American College of Surgeons (ACS) was referenced by the AUA web page. The ACS organized decision making into three different scenarios [11]. Phase 1 is the preparation phase for institutions and localities where COVID-19 cases are not in the rapid escalation phase, in which only a few patients are hospitalized, and beds and ICU ventilators not exhausted. In this setting, the regional leadership and surgical teams must plan to treat diseases as indicated, given that a delay in treatment could reduce the chance of being cured. Phase 2 and phase 3 are urgent settings where hospital resources are all routed to COVID-19. Pragmatically, four of the 15 papers provided the possibility of individualization of their recommendations according to different communities and hospital resources realities, using a tier system [2], [4], [5], [7]. A number of variables should be considered, such as availability of resources, whether a particular local institution is assessed as a COVID-free hospital, capacity of ICU beds and ventilators, and whether the curve has flattened.

Most of the articles reviewed are recommendations and not guidelines, primarily based on expert opinion. An exception is the EAU guidelines, which were a monumental effort proposed by a task force of 250 experts and provide evidence correlating the delay of treatment and clinical harm to survival or progression. In addition, the EAU clarifies that its guidelines are endorsed by national societies in 72 countries, providing a supporting document that urologists can use in teamwork and collaboration in their hospitals.

According to Lei et al [12], seven of 34 (20.5%) patients died after elective surgeries in Wuhan. At presentation, these patients were asymptomatic carriers and probably were in incubation phase or were infected at the hospital.

In many parts of the world, people have been asked to stay at home, and public health authorities made it mandatory to postpone elective surgery. Public health orders such as social distancing and lockdown appear to be effective at reducing the local spread of COVID-19. As the situation continues to evolve, including attempts at returning to the new normal and the threat of additional waves of infection being presented, these recommendations will require updating.

Considering uro-oncology, the pandemic has reinforced the concept of active surveillance for low-risk genitourinary tumors. Conversely, there is evidence that a delay of >3 mo has a negative impact on the survival of patients with urothelial tumors, particularly those at high risk, and such tumors should be managed with priority. While the majority of the articles included recommendations to postpone treatment for low- and intermediary-risk PCa, the scope of recommendations regarding high-risk PCa varied. For example, Kutikov et al [6] recommended that high-risk PCa should be treated immediately, Stensland et al [13] recommended that these patients should not be operated and they should be referred to radiotherapy, and Ribal et al [5] recommended that surgery can be postponed up to 3 mo or even after the COVID-19 situation has settled.

It is important to note that patients with obstructing and infected stones should be managed, preferably by immediate decompression. In patients who have risk factors, such as pre-existing indwelling ureteral stent, symptomatic, recurrent emergency visits, solitary kidney, and bilateral ureteral calculi, close monitoring for clinical progression is warranted by telehealth, with a low threshold for additional evaluation.

Most articles point toward taking precautions to avoid contamination in the operating room. The safety of the resterilization process of endourological materials is a concern. It is highly recommended to clean surfaces with appropriate disinfectants with proven activity against enveloped viruses (hypochlorite), as 0.02% chlorhexidine digluconate can be less effective [5]. Numerous uncertainties remain in laparoscopic/robotic surgeries. It is a general recommendation to avoid generating aerosols through manipulation of the trocars and pneumoperitoneum. Concerns have also been raised about the use of electrocautery and positive pressurization rooms.

In normal times, to proceed as planned to perform a cadaveric kidney transplantation is the rule. However, special attention is needed in emergency situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Proponents of postponement argue that renal transplantation is highly complex and may require intensive support from a multidisciplinary team, and resources directed to combat COVID-19 might be compromised.

The timing of ambulatory cystoscopy for the diagnosis of macroscopic hematuria was an area of disagreement. Although most authors recommend proceeding with investigation of macrohematuria, two guidelines (USANZ and EAU) suggest a delay between 1 and 2 mo.

Management of emergencies (eg, ischemic testicular torsion, low-flow priapism, clot retention, and trauma) should not be delayed.

There are several limitations in our systematic review. Although these guidelines reflect an impressive effort to quickly provide guidance to urologists during a rapidly evolving emergency, the methodological quality of most guidelines was considered to be low to moderate. The level of evidence did not differ much between guidelines, and all of them were based on expert opinions. No grading of recommendations was reported. Indeed, this review highlights the need for high-quality guidelines that could be referenced in the case of future pandemics or other major emergencies. In this review, we attempted to classify recommendations in a similar fashion to Goldman and Haber’s [4] priority tiers.

6. Conclusions

Multiple published recommendations exist to guide urology teams during the COVID-19 crisis. Recommendations support the use of active surveillance in lower-risk tumors (low-risk PCa, low-grade bladder cancer, and small renal masses), as well as considering omission of systemic therapies (neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatments) or cytoreductive nephrectomy in some advanced cases. Moreover, there was consensus to propose medical expulsive therapy for uncomplicated ureteral stones, but that infection and/or obstruction of the kidneys with a real risk of urosepsis or functional sequelae must be treated accordingly. Intravesical clots in active hematuria, infected implants, or postoperative hemorrhagic and ischemic complications are considered urological emergencies and must be treated immediately even at a time of pressure to the local health system.

Author contributions: Flavio Lobo Heldwein had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Heldwein, Lima, Carneiro, Wroclawski.

Acquisition of data: Heldwein, Wroclawski.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Heldwein, Loeb.

Drafting of the manuscript: Heldwein, Loeb.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Sridhar, Loeb, Teoh.

Statistical analysis: Heldwein.

Obtaining funding: None.

Administrative, technical, or material support: None.

Supervision: Wroclawski, Heldwein.

Other: None.

Financial disclosures: Flavio Lobo Heldwein certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: Flavio Lobo Heldwein received honorarium from Janssen. Stacy Loeb reports reimbursed travel from Sanofi and equity in Gilead. Fabio Sepulveda Lima reports reimbursed travel from Boston Scientific. Jeremy Yuen-Chun Teoh received honorarium from Olympus and Boston Scientific, travel grants from Olympus and Boston Scientific, and research grants from Olympus and Storz.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: Stacy Loeb is supported by the Edward Blank and Sharon Cosloy-Blank Family Foundation.

Associate Editor: Richard Lee

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2020.05.020.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/.

- 2.Ficarra V., Novara G., Abrate A., et al. Urology practice during COVID-19 pandemic. Minerva Urol Nefrol. In press. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0393-2249.20.03846-1.

- 3.USANZ. Guidelines for urological prioritisation during COVID-19. https://www.usanz.org.au/news-updates/our-announcements/usanz-announces-guidelines-urological-prioritisation-covid-19.

- 4.Goldman HB, Haber GP. Recommendations for tiered stratification of urologic surgery urgency in the COVID-19 era. J Urol. In press. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000001067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Ribal M.J., Cornford P., Briganti A. 2020. EAU Guidelines Office Rapid Reaction Group: An organization-wide collaborative effort to adapt the EAU guidelines recommendations to the COVID-19 era. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kutikov A., Weinberg D.S., Edelman M.J., Horwitz E.M., Uzzo R.G., Fisher R.I. A war on two fronts: cancer care in the time of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. In press. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Carneiro A., Wroclawski M.L., Nahar B. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the urologist’s clinical practice in Brazil: a management guideline proposal for low- and middle-income countries during the crisis period. Int Braz J Urol. 2020;46:501–510. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2020.04.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz E.G., Stensland K.S., Mandeville J.A., et al. Triaging office-based urology procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Urol. In press. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000001034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Metzler I.S., Sorensen M.D., Sweet R.M., Harper J.D. Stone care triage during COVID-19 at the University of Washington. J Endourol. 2020;34:539–540. doi: 10.1089/end.2020.29080.ism. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mottrie A. ERUS (EAU Robotic Urology Section) guidelines during COVID-19 emergency. https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/ERUS-guidelines-for-COVID-def.pdf.

- 11.American College of Surgeons. COVID-19 and surgery. https://www.facs.org/covid-19.

- 12.Lei S., Jiang F., Su W., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. EClinicalMedicine. In press. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Stensland K.D., Morgan T.M., Moinzadeh A. Considerations in the triage of urologic surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol. 2020;77:663–666. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed K., Hayat S., Dasgupta P. Global challenges to urology practice during COVID-19 pandemic. BJU Int. In press. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.15082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Lalani A.A., Chi K.N., Heng D.Y.C. Prioritizing systemic therapies for genitourinary malignancies: canadian recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can Urol Assoc J. 2020;14:E154–8. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.6595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quaedackers JSLT, Stein R, Bhatt N., et al. Clinical and surgical consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with pediatric urological problems: statement of the EAU Guidelines Panel for Paediatric Urology, March 30 2020. J Pediatr Urol. In press. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Proietti S., Gaboardi F., Giusti G. Endourological stone management in the era of the COVID-19. Eur Urol. In press. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Gillessen S., Powles T. Advice regarding systemic therapy in patients with urological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol. 2020;77:667–668. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.