Summary

Bariatric/metabolic surgery was paused during the Covid-19 pandemic. The impact of social confinement and the interruption of this surgery on the population with obesity has been underestimated, with weight gain and worsened comorbidities. Some candidates for this surgery are exposed to a high risk of mortality linked to the pandemic. Obesity and diabetes are two major risk factors for severe forms of Covid-19. The only currently effective treatment for obesity is metabolic surgery, which confers prompt, lasting benefits. It is thus necessary to resume such surgery. To ensure that this resumption is both gradual and well-founded, we have devised a priority ranking plan. The flow charts we propose will help centres to identify priority patients according to a benefit/risk assessment. Diabetes holds a central place in the decision tree. Resumption patterns will vary from one centre to another according to human, physical and medical resources, and will need adjustment as the epidemic unfolds. Specific informed consent will be required. Screening of patients with obesity should be considered, based on available knowledge. If Covid-19 is suspected, surgery must be postponed. Emphasis must be placed on infection control measures to protect patients and healthcare professionals. Confinement is strongly advocated for patients for the first month post-operatively. Patient follow-up should preferably be by teleconsultation.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, Covid-19, Pandemic, Guidelines, Obesity

Introduction

Since March 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic has caused scheduled weight-loss surgery and related therapeutic education programmes (preparation and follow-up) to be paused. The expected duration of the pandemic is uncertain (vaccine unavailable in the short term), acquired immunity is unsure (short-lived antibodies), and obesity and comorbidity rates have been increasing. De-scheduling and confining have numerous adverse effects, including psychological harms, injudicious dietary behaviour, and lack of physical exercise [1]. These effects in turn cause weight gain or regain [2], worsened comorbidities, a risk of contracting a severe form of Covid-19, and increased morbidity/mortality risk in future candidates for weight-loss surgery.

To mitigate these harms arising from the epidemic and the resulting confinement, and to better prepare this vulnerable section of the population for an extension of the epidemic, there is an obvious real need to resume weight-loss surgery. It is therefore urgent to set guidelines for the gradual resumption of surgical care, especially as the conventional indications for this surgery based on BMI reflect neither the severity of the obesity nor the urgency or semi-urgency of some indications.

The SOFFCO-MM tasked an expert working group with addressing these questions in readiness for the resumption of surgery. The aim of these guidelines is to cogently rank the urgency of rescheduling surgery based on evidence-based criteria, benefit/risk ratios and clinical good sense.

Why resume weight-loss surgery?

Benefit of weight-loss surgery on overweight and comorbidities

Obesity increases the risk of illnesses such as diabetes, high blood pressure, hepatic steatosis and steatohepatitis, coronopathy, stroke, certain cancers, infertility, psychosocial disorders, arthropathy, nephropathy and many others. Epidemiological studies confirm that severe obesity reduces life expectancy by 5–20 years [3].

Among the complications linked to obesity, some are especially life-threatening or potentially disabling It is estimated that two thirds of persons with diabetes will die of a cardiovascular illness with a relative risk 1.8–2.6 times higher than the general population [4]. Similarly, the presence of an obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome is especially frequent in persons with obesity, and if untreated is associated with an excess mortality of 24% at 1.5–2 years [5].

It is currently proven that the only effective long-term treatment of obesity is surgery. Besides improving comorbidities, weight-loss surgery reduces the relative risk of death by 35–89% [6]. Weight-loss surgery has lengthened life expectancy, despite the peri-operative risks [7]. Peri-operative mortality has tended to diminish with time and accumulated experience, with rates in France now of 0.07% [8]. This is true metabolic surgery: its other benefits, especially on diabetes, are detailed in the other chapters.

Impact of obesity on disease severity in Covid+ patients

Persons with obesity are among those most vulnerable to the Covid-19 epidemic, obesity being an independent complications factor: a recent study found that more than 47% of infected patients admitted to IC had obesity. Obesity significantly increased the risk of being placed under invasive artificial ventilation. In the Lille study, Grade II and III obesity in patients admitted to IC for Covid-19 was an independent risk factor for a severe form of the infection [9].

Despite improved knowledge of Covid-19, there are still no data supporting a protective effect of bariatric surgery in patients who have undergone it, although the weight loss itself probably mitigates the consequences of infection. Nor are there any data by which to judge the impact of infection during the weight loss period. Special vigilance is thus called for.

Who is eligible for scheduled bariatric surgery? In what setting?

Resumption of surgical care must allow for a possible ‘second wave’ or medium-term extension of the epidemic after confinement measures are lifted. An extreme vigilance is necessary concerning the indicators that govern response to reduce the risk of peri-operative Covid-19 infection:

-

•

access to Intensive care (IC) after the crisis;

-

•

replication rate of the virus less than 1 outside epidemic peaks;

-

•

access to operating room: several factors hinder access to the operating room. Physical distancing measures in healthcare centres reduce the fluidity and availability of accommodation (which depends on policy decisions made by the centre) and there may also be shortages of medical drugs (independently of the centre and the healthcare professionals).

There are two contrasting strategies by which weight-loss surgery can be resumed. Each has its justifications, its advantages, and its drawbacks. Table 1 summarizes these two strategies.

-

•

strategy 1 (‘benefit outweighs risk’) is based on the severity scores for each pathology. Several studies propose prioritizing indications by considering the degree of severity of the associated comorbidities and the socioeconomic impact [10], [11], [12], [13]. In this strategy, and especially in the case of blood sugar imbalance, need for insulin therapy, or diabetes evolving for more than 5 years and the occurrence of macro- or microangiopathy are factors of poor outcome. However, these patients are also the most at risk in the event of surgical complications [13];

-

•

strategy 2 (‘safe and preventive’), conversely, consists in operating only on patients at low operative risk to achieve a longer-term benefit.

Table 1.

Strategies for resuming bariatric surgery.

| What patients? | Justification | Advantages | Risks | Needs for IC beds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy 1 ‘Benefit outweighs risk’ |

Operate on patients whose need is high | Deterioration in health very probable within 6 months | Very high benefit if post-operative effects are simple | Some of these patients have the highest risk of complications | High |

| Strategy 2 ‘Safe and preventive’ |

Operate on patients with the least possible comorbidities | Reduces the number of patients with obesity on waiting lists for weight-loss surgery, so reducing the number of vulnerable patients | Benefits high but less than in Strategy 1 | Patients are less at risk This strategy is not very realistic |

Rare |

| Strategy 3 ‘SOFFCO guidelines’ |

Operate on patients whose need is high provided the risk of morbidity is very low | 1/This metabolic surgery is the only effective treatement for obesity 2/Mitigates excess mortality linked to obesity |

1/Very favourable benefit/risk ratio at both individual and public health scales 2/Reduction of comorbidities linked to obesity with less operating risk |

Low | Rare |

To guide decision-making during this unprecedented health crisis, the SOFFCO-MM set objectives according to means:

-

•

make as little use of IC beds as possible by selecting patients whose expected surgical complication rates will be low;

-

•

perform bariatric surgery on those categories of patient whose state of health will deteriorate in the medium term without surgical care;

-

•

resume this surgical care equally in both public and private sectors;

-

•

do not operate on Covid+ patients or patients with known Covid+ history (given the current lack of evidence for effective immunization).

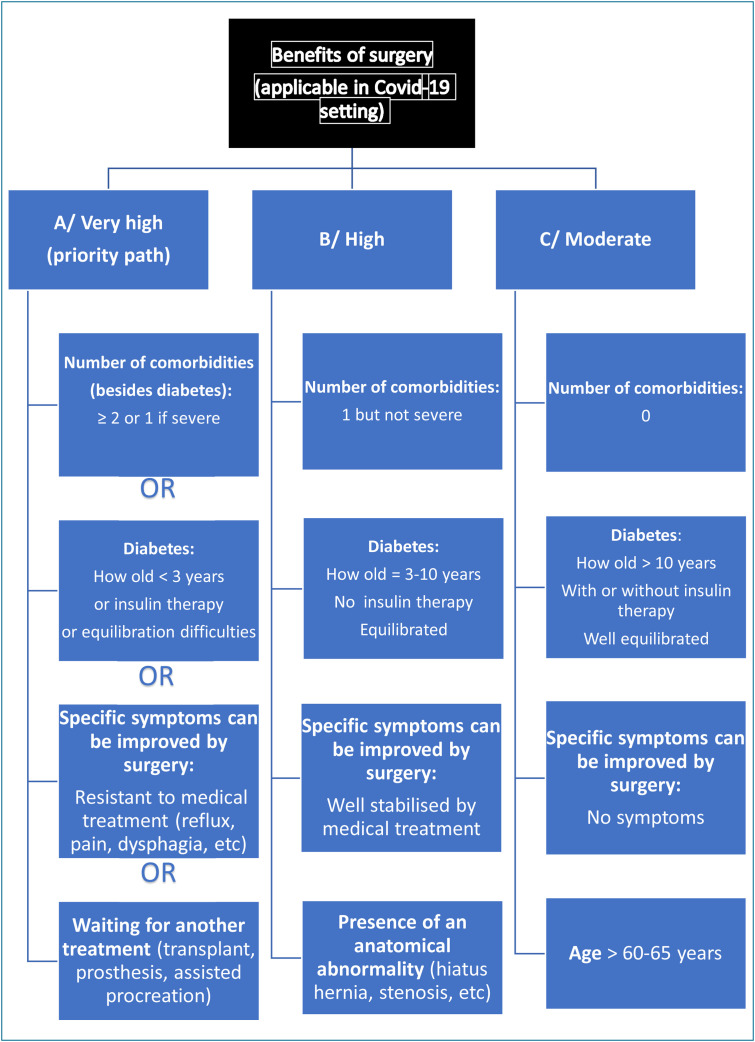

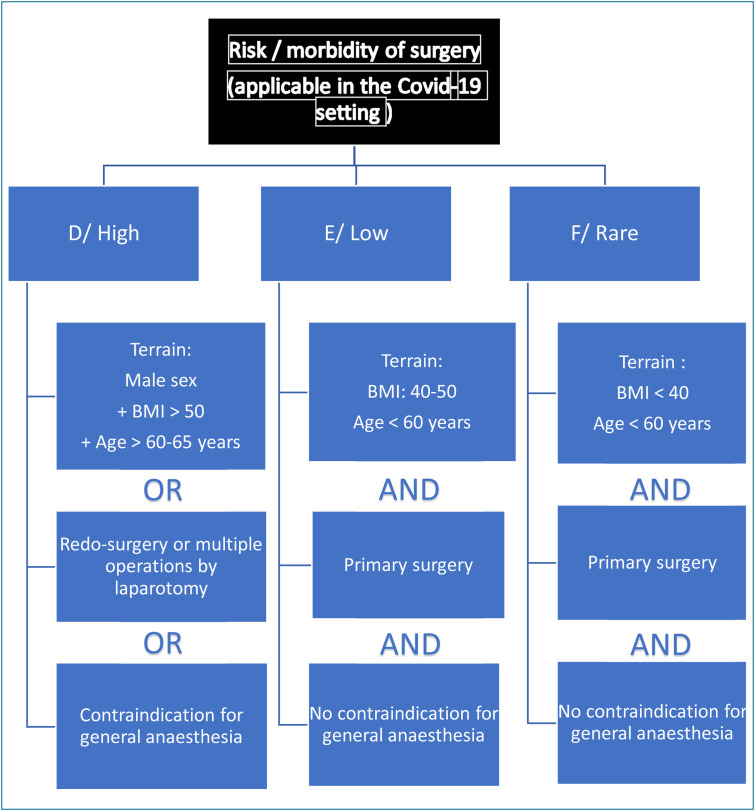

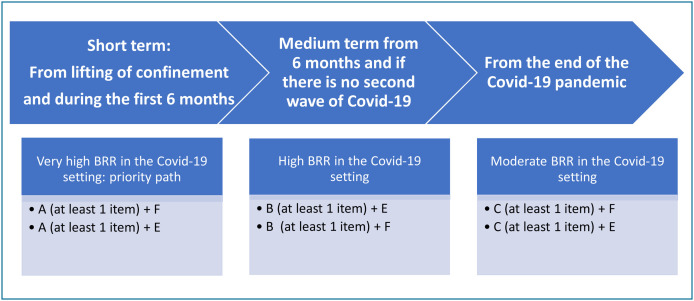

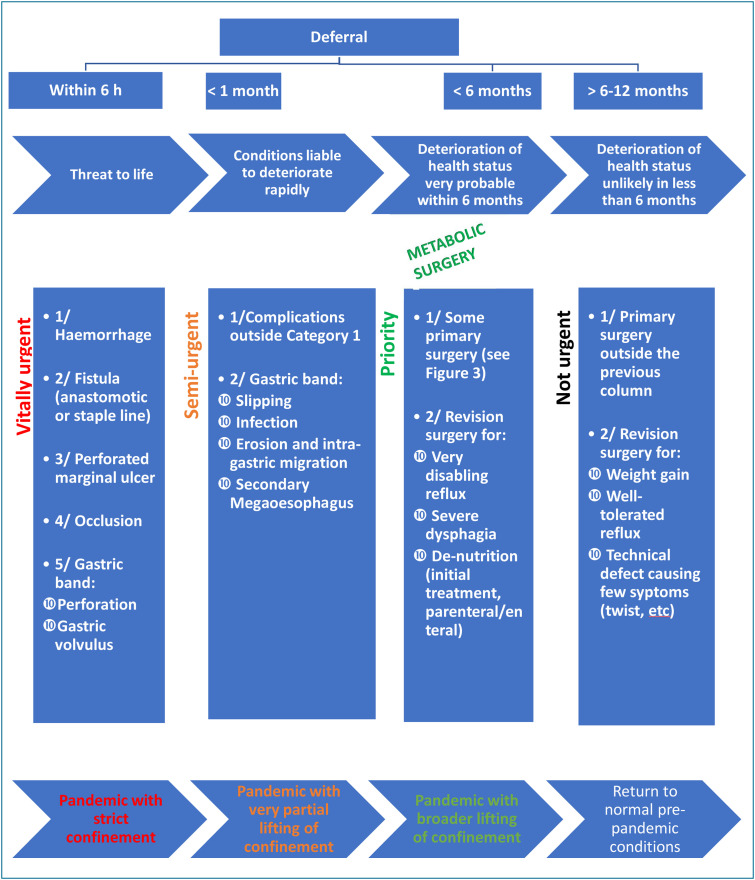

Strategy 3 advocated by the SOFFCO (Table 1) is a degraded intermediate strategy based on benefit/risk ratios. The flow charts for indications are summarized in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 . Fig. 4 shows the flow chart for all indications (vitally urgent, semi-urgent, priority and not urgent). In other words, priority patients (for surgery when confinement is lifted and in the subsequent 6 months) will have the following characteristics:

Figure 1.

Benefits of weight-loss surgery by category during the Covid-19 crisis.

Figure 2.

Risks of morbidity in weight-loss surgery by category during the Covid-19 crisis.

Figure 3.

Categories of patients undergoing primary weight-loss surgery in the current Covid-19 setting. BRR: benefit/risk ratio.

Figure 4.

Resumption of overall activity according to the evolution of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Decision of multidisciplinary concertation meeting:

-

•

already validated;

-

•

being validated.

Indication (further criterion to be added to the multidisciplinary concertation file to qualify for priority ranking):

-

•

diabetes:

-

∘

time since diagnosis < 3 years, or,

-

∘

needing insulin treatment, or,

-

∘

with equilibration difficulties, or;

-

•

comorbidities (other than diabetes):

-

∘

≥ 2 comorbidities, or,

-

∘

1 severe comorbidity, or;

-

•

waiting for other important treatment (organ transplant, joint prosthesis, medically assisted procreation), or;

-

•

with specific symptoms that can be improved by surgery because they are resistant to medical treatment (gastro-oesophageal reflux, pain, dysphagia, etc.).

The priority criteria proposed are established according to the severity of the comorbidities and the benefit/risk ratios for surgery. These criteria are tools to guide resumption of bariatric surgery. They are to be weighted according to the local status of the epidemic, the types of patients in each centre, and the procedures envisaged. There will be disparities between patients from one centre to another. Some centres will have small numbers of group A patients (Fig. 1). A group B patient scheduled for bariatric surgery in a centre barely affected by the epidemic may thus be operated on despite a lower priority, with a favourable benefit/risk ratio. In all cases, patents must be warned of the risks, and their informed written consent obtained systematically.

Each bariatric surgery centre will have a list of patients whose indications have been validated by multidisciplinary concertation after a preparation lasting more than 6 months. The ways in which care will be resumed will vary from one centre to another according to the human, physical, and medication resources of each entity. No guidelines are therefore given concerning care resumption thresholds. The priority is to avoid having to deny care. Patients on waiting lists are to be re-contacted by the multidisciplinary teams to keep in touch, continue follow-up and prepare them for surgery. The objectives are weight control with weight stability, stabilization of any comorbidities, particularly in patients with diabetes, and achievement of optimal blood sugar levels. Teleconsultation is to be preferred and can be replaced by telephone contact for persons without Internet access.

What surgical techniques and indications are to be preferred for scheduled bariatric surgery?

The surgical techniques that can be used during a pandemic are those validated by the public health regulatory authorities [14]. There is no reason to prefer, in first line surgery, one surgical technique over another as regards the two most frequent weight-loss operations performed in France, namely sleeve gastrectomy and the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, as the rate of complications [15], [8] and short-term weight loss are similar [16]. In a pandemic setting, it may be preferable to avoid malabsorptive surgery when the de-nutrition risk is higher, and the follow-up of patients may be more difficult.

The surgical indications to be preferred in the case of scheduled surgery are those designated as primary surgery. Morbidity rates are lower than for secondary surgery irrespective of the type of surgery [17], [18], hospital stay duration being generally shorter [19], and efficacy for weight loss probably greater [20].

Concerning secondary surgery, a distinction must be made between surgery for weight regain or insufficient weight loss, and surgery for complications and/or sequelae of earlier surgery.

Concerning secondary surgery for weight loss, the best strategy would be to wait for the pandemic/epidemic to abate locally or regionally. As explained above, such surgery has an increased rate of complications and very wide-ranging weight loss results according to the technique and the indication. Continued nutritional and/or psychological follow-up by telemedicine offers a good alternative that can help optimise and/or maintain preparation for later surgery.

Concerning secondary surgery for complications or for secondary effects of earlier weight-loss surgery, there are several distinct cases. First, the indications when there is a short-term threat to life, e.g., the presence of a chronic post-operative digestive fistula resistant to endoscopic treatment. In this type of indication, the alternative with continued endoscopic treatment may be hazardous after a certain time lag, with the appearance of other even worse complications [21], [22]. In this type of case, surgery must be performed in a care centre where post-operative IC and/or continuous care with a Covid – circuit is possible. If not, transfer to a care centre that can offer these services is preferable. This type of strategy also holds for post-operative digestive stenosis if several endoscopic treatments have been necessary and have failed to relieve the patient's symptoms lastingly.

For indications where there is no short-term threat to life, it is preferable to have recourse to surgery at a time when the epidemic is at a lull, and if medical treatment has failed. For example:

-

•

in the case of disabling reflux after sleeve gastrectomy, medical treatment by continued hygiene and diet measures, continued treatment by a proton pump inhibitor associated or not with antacids;

-

•

in the case of severe de-nutrition when revision or reversal surgery is envisaged, it is preferable to defer the operation and continue with nutritional support of the enteral or parenteral nutrition type that can be given at home.

Concerning robot-assisted bariatric surgery, no literature data contraindicate this type of surgical approach. The choice of this support over a conventional laparoscopic approach will depend on the surgeon's experience in robot-assisted surgery.

Clinical pathway to bariatric surgery for a Covid-negative patient

Pre-operative stage

Patients must be called on the day before consultations to make sure they have no symptoms that point to a Covid-19 infection [23]. The consultations must be spaced with no waiting time. The patients must wear a mask. The patients must be warned that there is a risk of nosocomial Covid-19 infection. Patient education programmes must be delivered with a limited number of patients in one small group (at most 5 persons) or remotely. During patient education programmes for weight-loss surgery, if videoconferencing is impossible, the number of persons present must be kept to a strict minimum. Physical presence is thus not compulsory, and a go-ahead certificate in the patient's file will suffice. Any bariatric surgeon who displays symptoms suggesting Covid-19 infection should be tested. If the test is positive, then the surgery must be performed by another bariatric surgeon (in the same or a different centre) if that surgery is urgent or semi-urgent.

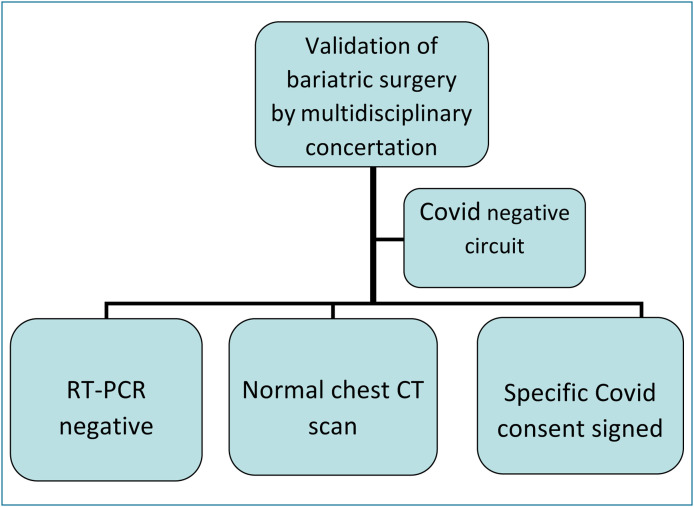

Peri-operative stage/COVID – circuit

An RT-PCR screening test (nasopharyngeal swab) must be carried out at surgery D–2. The patient goes to a reception service at the centre and undergoes the test as an outpatient. Ideally, patients, even if asymptomatic, should take a pre-operative PCR test or serological test. However, the SOFFCO-MM is aligned with the guidelines of other learned societies concerning infection status. The patient is told the results of the test by the surgeon before admission on the day before the surgery.

If the test is positive, then the surgery is cancelled, because the risks of respiratory complications or death are increased [24]. However, the obesity follow-up must be ensured by protocols specific to Covid+ patients. Care for persons with obesity and suspected Covid-19 infection is still the same as for the general population. A minimum time of one month before rescheduling seems reasonable, with in all cases a clinical and biological reassessment and a Covid-19 expert opinion.

If the test is negative, a chest CT scan is recommended to look for any abnormality suggestive of a Covid-19 infection (frosted glass appearance, pleuro-pneumopathy, etc). This scan must be carried out at surgery D–1 to limit the risk of performing anaesthesia on an asymptomatic Covid-19 patient. These screening procedures (RT-PCR on naso-pharyngeal swab, chest CT scan), drawn up from knowledge available at the time they were issued, may evolve as new findings emerge. The patient's consent must be checked and signed. This consent must state the risk of nosocomial Covid-19 infection and commit the patient to post-operative home confinement (Fig. 5 ).

Figure 5.

Preoperative measures before scheduled surgery.

On admission and on the day of surgery, a complete examination, including temperature measurement, must be performed [25]. All healthcare professionals must wear a surgical mask whenever they come close to patients. Treatment by night ventilation for patients with a sleep apnoea syndrome must also be continued [26].

Post-operative stage and confinement

If the patient's condition permits, we recommend that the hospital stay be as short as possible. The patients should be included in bariatric protocols of the fast-track type (early mobilisation and feeding) to shorten hospital stay. During the pandemic, bariatric surgery can be performed on outpatients provided the surgery team were recognised experts in this field before the pandemic [27]. A hospital stay duration of two days is acceptable for simple cases.

It is strongly advised that the patient remain confined at home for the first month post-operatively. The initial weight loss may be rapid in the first month, which can increase the risk of contracting a severe form of Covid-19 [2]. Post-operative follow-up consultations must be by telemedicine. Follow-up remains multidisciplinary and adapted to the patient (individualised): primary care physician, nutritionist, surgeon, dietitian, nurse, and psychologist. The frequency of follow-up must be the same as that set by the centre in which the bariatric surgery was performed and comply with the HAS 2009 guidelines. A first teleconsultation or consultation by telephone should be carried out in the week following the patient's discharge from hospital (highest rate of complications) and then at one month. A dematerialised follow-up programme via smartphone is also suitable during this period. The SOFFCO-MM emphasises the utility of post-operative nutritional and psychological follow-up because the risk of de novo depression occurring increases after this surgery [28]. It is preferable to favour delivery of medication, including vitamin supplements, directly by the pharmacy or via nursing care at home, if medication prescribed at discharge could not be purchased beforehand.

In view of the unusual nature and uncertainty of the current period, bariatric surgery can be envisaged only with complete records for all the patients operated on, and medium-term follow-up at 6 months post-operatively. The aim of this follow-up and data collection is to check for the absence of excess mortality arising from the resumption of bariatric surgery, which will be regularly monitored. If there is no added mortality risk, the operating indications can be re-assessed to allow wider provision of surgery. In parallel to the existing register in place at the SOFFCO-MM, indicators specific to the current epidemic setting will be added. Procedures for collecting data specific to Covid-19 are the same as those for the current SOFFCO-MM register.

Urgent medical and surgical care for patients with obesity, and care for bariatric surgery complications

This section applies equally to patients operated on during and before the pandemic. Some 1% of French nationals have a weight-loss surgery history. Confinement causes psychological stress, fosters self-medication (e.g. NSAIDs), and favours the resumption of addictive behaviour such as tobacco use and other addiction disorders. Special attention must be paid to patients aged over 60 [29] and who have a history of weight-loss surgery. This is especially relevant if the patient has an associated comorbidity such as diabetes, HT or respiratory insufficiency [30]. All unnecessary or dispensable steps or procedures liable to impede care provision must be eliminated.

Initial stance to be taken when there is a medical or surgical problem in a patient with obesity in a Covid-negative stream

The organisation of elective surgery programmes and their follow-up permits an orderly, controlled patient flow. The advent of a complication and the emergency it may create can upset this regulation. It is essential to dissuade patients from coming to the hospital for no good reason, but also to ensure that any complication underestimated by a patient does not evolve threateningly. Teleconsultation and public health insurance cover currently allow a first selection of patients. It is therefore essential to set in place rapid access to teleconsultation to avoid excessive recourse to emergency services, especially at busy times. After this teleconsultation, it will be possible to direct the patient towards simple monitoring or, if a physical examination is necessary, towards a rapid physical consultation or emergency admission. This system seems reasonable in working hours. The patient must be encouraged to elicit the emergency services only when a teleconsultation is impossible outside working hours. To summarize: every medical or surgical problem in a patient with obesity must be dealt with in a consultation (ideally a teleconsultation) with the referring physician or with a specialist physician or surgeon. These last will decide whether the patient must come in person for care at the hospital.

Opinion of a bariatric surgeon in urgent cases

Even in a setting where Covid-19 infection must be suspected, any patient with or without a recent history of weight-loss surgery who presents signs such as a cough, high temperature, abdominal pains, tachycardia or other digestive signs (nausea, diarrhoea) requires a prompt opinion from a surgeon specialised in weight-loss surgery to prevent unwarranted delay in surgical care. This is particularly important as some clinical signs that point to Covid-19 infection can be post-operative effects (simple or complicated) of bariatric surgery.

Avoid general anaesthesia as much as possible

Whenever possible, general anaesthesia must be avoided because of the heightened risk of respiratory complications needing IC monitoring, or of finding and worsening an occult Covid-19 pneumopathy [9]. Local anaesthesia (e.g. drainage of cutaneous abscesses on scars), or locoregional anaesthesia must be favoured as much as possible.

The least invasive, shortest, and most effective treatment

Even though this rule already holds outside pandemics, it is preferable to use all the therapeutic means available, starting with the least invasive. For example, in the case of a post-sleeve fistula without serious signs, a conservative treatment (radiological drainage and endoscopic treatment) must be tried. In the case of resumed bariatric surgery, laparoscopy should if possible be the preferred approach rather than laparotomy owing to its shorter hospital stay time and lower risk of post-operative respiratory complications.

This resumed surgery must be effective and fast at the outset. Possible Covid-19 infection that would require the opinion of the local Covid-19 crisis unit must be constantly watched for.

Think of medical complications after weight-loss surgery

Certain signs pointing to Covid-19 infection (ageusia, dizziness, etc.) can also be neurological signs of post-operative complications after weight-loss surgery. Among these complications, we note de-nutrition, which must be treated urgently, because it is on the list of risk factors for severe forms of Covid-19. Vitamin deficiencies may also be responsible for unsteady balance or confusion (vitamin B1 deficiency). These symptoms are rare in Covid-19. Such deficiency must be corrected urgently with thiamine by the parenteral route, avoiding glucose-rich serum, which causes lysis of nerve cells. Sensitivity disorders, tingling and diplopia point to possible vitamin B12 deficiency and are not recognised signs of Covid-19 [31].

Conclusions

These SOFFCO-MM guidelines are designed to allow resumption of bariatric surgery through appropriately adapted pre-, peri- and post-operative procedures to ensure the safe care of persons with obesity after confinement is lifted.

Highlights.

-

•

Obesity is a risk factor for severe forms of Covid-19.

-

•

Weight-loss surgery is the only effective treatment for obesity, offering prompt, lasting benefit.

-

•

Weight-loss surgery is a metabolic surgery that improves metabolic syndrome (diabetes, HT, etc.).

-

•

Resumption must be gradual and adapted to the current health risk. It will vary regionally.

-

•

Weight-loss surgery must be deferred in the case of Covid-19 infection or recent history of Covid-19 (immunisation uncertain).

-

•

No single surgical technique is to be preferred among those validated by the public health regulating authorities.

-

•

A Covid-negative circuit must be put in place.

-

•

Any medical or surgical problem in a patient with obesity must be dealt with in a consultation (ideally a teleconsultation) with the referring physician or the specialist physician or surgeon. The latter will decide whether the patient must come for care to the hospital.

-

•

The possibility of Covid-19 infection must be entertained at all stages of care.

-

•

Resumption of surgery can be envisaged only with complete records of patients operated that include data specific to Covid-19.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Contributor Information

S. Msika, Email: simon.msika@aphp.fr.

Remerciement comité de lecture:

R. Abittan, A. Abou-Mrad, L. Arnalsteen, R. Arnoux, T. Auguste, S. Benchetrit, B. Berthet, J.-C. Bertrand, L.-C. Blanchard, J.-L. Bouillot, R. Caiazzo, J.-M. Catheline, J.-M. Chevallier, J. Dargent, P. Fournier, V. Frering, J. Gugenheim, H. Johanet, D. Lechaux, P. Leyre, A. Liagre, J. Mouiel, D. Nocca, G. Pourcher, F. Reche, M. Robert, H. Sebbag, M. Sodji, G. Tuyeras, and J.-M. Zimmermann

References

- 1.Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation de l’environnement et du travail . ANSES; Paris: 2020. Avis relatif à l’évaluation des risques liés à la réduction du niveau d’activité physique et à l’augmentation du niveau de sédentarité en situation de confinement. https://www.anses.fr/fr/system/files/NUT2020SA0048.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.HAS. Réponses rapides dans le cadre du COVID-19 – Pathologies chroniques et risques nutritionnels en ambulatoire. Validée par le Collège le 16 avril 2020.

- 3.Fontaine K.R., Redden D.T., Wang C., Westfall A.O., Allison D.B. Years of life lost due to obesity. JAMA. 2003;289:187–193. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf.

- 5.Hartemink N., Boshuizen H.C., Nagelkerke N.J., Jacobs M.A., van Houwelingen H.C. Combining risk estimates from observational studies with different exposure cutpoints: a meta-analysis on body mass index and diabetes type 2. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1042–1052. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sjöström L., Narbro K., Sjöström C.D. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–752. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sjöström L. Bariatric surgery and reduction in morbidity and mortality: experiences from the SOS study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(Suppl 7):S93–S97. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazzati A., Audureau E., Hemery F. Reduction in early mortality outcomes after bariatric surgery in France between 2007 and 2012: a nationwide study of 133,000 obese patients. Surgery. 2016;159:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simonnet A., Chetboun M., Poissy J. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020 doi: 10.1002/oby.22831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casimiro Pérez J.A., Fernández Quesada C., Del Val Groba Marco M. Obesity Surgery Score (OSS) for Prioritization in the Bariatric Surgery Waiting List: a Need of Public Health Systems and a Literature Review. Obes Surg. 2018;28:1175–1184. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-3107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padwal R.S., Pajewski N.M., Allison D.B., Sharma A.M. Using the Edmonton obesity staging system to predict mortality in a population-representative cohort of people with overweight and obesity. CMAJ. 2011;183:E1059–E1066. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Maria E.J., Portenier D., Wolfz L. Obesity surgery mortality risk score: proposal for a clinically useful score to predict mortality risk in patients undergoing gastric bypass. Sure Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuk J.L., Ardern C.I., Church T.S. Edmonton Obesity Staging System: association with weight history and mortality risk. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36:570–576. doi: 10.1139/h11-058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_765529/fr/obesite-prise-en-charge-chirurgicale-chez-l-adulte

- 15.Zellmer J.D., Mathiason M.A., Kallies K.J., Kothari S.N. Is laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy a lower risk bariatric procedure compared with laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass? A meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2014;208:903–910. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.08.002. [discussion 909-10] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterli R., Wölnerhanssen B.K., Vetter D. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-Y-Gastric bypass for morbid obesity-3-year outcomes of the prospective randomized Swiss Multicenter Bypass Or Sleeve Study (SM-BOSS) Ann Surg. 2017;265:466–473. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Chaar M., Stoltzfus J., Melitics M., Claros L., Zeido A. 30-day outcomes of revisional bariatric stapling procedures: first Report Based on MBSAQIP Data Registry. Obes Surg. 2018;28:2233–2240. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu J., Lundberg P.W., Javier Birriel T., Claros L., Stoltzfus J., El Chaar M. Revisional bariatric surgery for weight regain and refractory complications in a single MBSAQIP Accredited Center: what are we dealing with? Obes Surg. 2018;28:2789–2795. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keren D., Romano-Zelekha O., Rainis T., Sakran N. Revisional bariatric surgery in Israel: findings from the Israeli bariatric surgery registry. Obes Surg. 2019;29:3514–3522. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-04018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahawar K.K., Graham Y., Carr W.R. Revisional Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review of comparative outcomes with respective primary procedures. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1271–1280. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1670-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rebibo L., Bartoli E., Dhahri A. Persistent gastric fistula after sleeve gastrectomy: an analysis of the time between discovery and reoperation. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva L.B., Moon R.C., Teixeira A.F. Gastrobronchial fistula in sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass--a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1959–1965. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1822-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Available from: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/covid-19_fiche_medecin_v16032020finalise.pdf.

- 24.Lei S., Jiang F., Su W. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;21:100331. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeo D., Yeo C., Kaushal S., Tan G. COVID-19 & the general surgical department – measures to reduce spread of SARS-COV-2 among surgeons. Ann Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epidémie COVID-19 Conseils aux personnes en situation d’obésité ou opérées d’une chirurgie bariatrique pendant la période de confinement, 10 avril 2020. Available from: http://sf-nutrition.org/covid-19-confinement-et-obesite-conseils-a-destination-des-patients/.

- 27.Rebibo L., Dhahri A., Badaoui R., Dupont H., Regimbeau J.M. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as day-case surgery (without overnight hospitalization) Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jakobsen G.S., Småstuen M.C., Sandbu R. Association of bariatric surgery vs. medical obesity treatment with long-term medical complications and obesity-related comorbidities. JAMA. 2018;319:291–301. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lighter J., Phillips M., Hochman S. Obesity in patients younger than 60 years is a risk factor for Covid-19 hospital admission. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa415c. ciaa415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang B., Li R., Lu Z., Huang Y. Does comorbidity increase the risk of patients with COVID-19: evidence from meta-analysis. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:6049–6057. doi: 10.18632/aging.103000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Y., Xu X., Chen Z. Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.031. [S0889-1591(20)30357-3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]