Identification of a previously overlooked spontaneous Hall effect mechanism creates opportunities in low-dissipation spintronics.

Abstract

Electrons, commonly moving along the applied electric field, acquire in certain magnets a dissipationless transverse velocity. This spontaneous Hall effect, found more than a century ago, has been understood in terms of the time-reversal symmetry breaking by the internal spin structure of a ferromagnetic, noncolinear antiferromagnetic, or skyrmionic form. Here, we identify previously overlooked robust Hall effect mechanism arising from collinear antiferromagnetism combined with nonmagnetic atoms at noncentrosymmetric positions. We predict a large magnitude of this crystal Hall effect in a room temperature collinear antiferromagnet RuO2 and catalog, based on symmetry rules, extensive families of material candidates. We show that the crystal Hall effect is accompanied by the possibility to control its sign by the crystal chirality. We illustrate that accounting for the full magnetization density distribution instead of the simplified spin structure sheds new light on symmetry breaking phenomena in magnets and opens an alternative avenue toward low-dissipation nanoelectronics.

INTRODUCTION

The spontaneous Hall voltage arises when the electrons gain transverse velocity due to certain internal magnetic structures. The associated Hall conductivity is the antisymmetric dissipationless part of the conductivity tensor, which corresponds to the Hall pseudovector σ that determines the Hall current (1–3)

| (1) |

Here, E is the applied electric field, σ = (σzy, σxz, σyx), σij are the antisymmetric Hall conductivity components, and jH is the Hall current transverse to E and σ. Apart from being odd under time reversal (T), Eq. 1 explicitly highlights that the Hall effect transforms like a pseudovector under spatial symmetry operations, i.e., it transforms like a magnetic dipole moment. This implies that the spontaneous Hall effect (in the absence of an external field) can occur only in materials with a magnetic space group (MSG) in which a net magnetic moment is allowed by symmetry (2, 4–7). Since the linear response σ is invariant under the spatial inversion (P), its components allowed by symmetry can be determined from the magnetic Laue group (MLG) (2, 4, 5). In this work, we go beyond the mere MLG symmetry requirements on the spontaneous Hall effect by focusing on its microscopic physical mechanisms and chemistry of favorable material candidates, on the magnitude and means to control and detect the effect, and on links to the electronic structure topology.

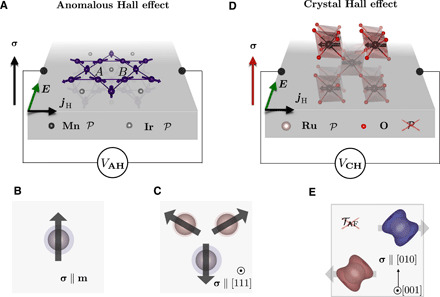

In the conventional microscopic mechanism of the spontaneous Hall effect in ferromagnets, the asymmetry of left-right deflected electrons is induced by the combined effect of ferromagnetic spin polarization and spin-orbit coupling (SOC) (2). This mechanism is commonly referred to as the anomalous Hall effect (AHE). Here, the ferromagnetic polarization breaks the T symmetry, while SOC adds breaking of the invariance under spin rotation, which, if the invariance was present, would make the AHE vanish as the invariance under T (6). This required symmetry breaking and associated emergent magnetic Berry curvature can arise also because of certain noncollinear antiferromagnetic structures instead of ferromagnetic moments, as predicted for Mn3Ir (8, 9), whose magnetic lattice is shown in Fig. 1A. Large AHE conductivities were experimentally reported in related coplanar noncollinear compensated antiferromagnets Mn3Sn (10), Mn3Ge (11), and Mn3Pt (12). The nonrelativistic AHE counterpart, the topological Hall effect, can occur when in the breaking of the spin-rotation invariance the SOC is replaced by a noncoplanar spin structure as shown in certain spin-liquid candidates (13), noncoplanar antiferromagnets (14), or skyrmions (15).

Fig. 1. Anomalous versus crystal Hall effect and corresponding magnetization isosurfaces.

(A) Anomalous Hall effect due to a Hall vector (σ) generated by the noncollinear antiferromagnetic order (purple arrows) in Mn3Ir (Mn. dark spheres; Ir, gray spheres). Mn and Ir atoms occupy centrosymmetric sites. The conventional symmetry breaking mechanism in anomalous Hall effect in ferromagnets (B) (m marks the magnetization vector) or noncollinear antiferromagnets (C) can be captured by the spin structure of the magnetic ions only (black arrows). (D) Crystal Hall effect generated by collinear antiferromagnetism (black arrows) and arrangement of nonmagnetic atoms (Ru, light brown spheres; O, red spheres). While the crystal has an inversion center at the magnetic Ru atom, the nonmagnetic O atoms are at noncentrosymmetric positions. (E) In the case of the crystal Hall antiferromagnet, the complete magnetization density shape is required to capture the spontaneous symmetry breaking. In (B), (C), and (E), we illustrate magnetization density isosurfaces with projection along the [100] direction.

The formal MLG symmetry analysis of the spontaneous Hall effect has not led, over the five decades since its original report (4), to the identification of a suitable material candidate with collinear antiferromagnetic order. Focusing on the spin vectors and spatial configurations of magnetic atoms (6), as illustrated in Fig. 1 (B and C), has even resulted in a general expectation of a vanishing spontaneous Hall effect in collinear antiferromagnets (6, 14, 16, 17). Antiferromagnets with T symmetry in the MLG (18) are excluded from having the spontaneous Hall effect. Examples encompass collinear antiferromagnets that have a symmetry termed here as , combining T and another symmetry operation, as for instance CuMnAs (19) () or GdPtBi (20) (, where is a half-unit cell translation).

The breaking of the T symmetry in the MLG by the spin structure of ferromagnets or the noncollinear magnetic systems has been at the heart of all the above Hall effect considerations. In this work, we introduce an alternative relativistic spontaneous Hall mechanism. Here, the simplified magnetic structure alone, represented by the spin vectors and spatial configurations of magnetic atoms, generates no spontaneous Hall conductivity. The required asymmetry is generated only when including additional atoms at noncentrosymmetric sites, which can be nonmagnetic. Our mechanism is demonstrated on the collinear antiferromagnet RuO2 shown in Fig. 1D. Here, the crystal arrangement of oxygen atoms results in the asymmetry of magnetization density on the opposite Ru spin sublattices, as illustrated in Fig. 1E, which breaks . This shows that while the symmetry breaking mechanism in ferromagnets or noncollinear antiferromagnets can be captured by drawing magnetic ordering as spin-projection vectors only, placed on the magnetic atom sites (Fig. 1, B and C), this common approach is incomplete in general. On the example of a collinear antiferromagnetic order, we illustrate that the detailed shape of the magnetization density needs to be considered; otherwise, important families of magnets are omitted.

A specific consequence of our crystal symmetry breaking mechanism in the context of the spontaneous Hall effect is flipping off the sign of the Hall coefficient when reversing the crystal chirality by the rearrangement of the nonmagnetic atoms while keeping the spin vectors and the positions of magnetic atoms fixed. The crystal chirality, thus, offers an additional tool, apart from reversing the magnetic moments, to control the sign of the Hall effect, which is not available in the earlier identified AHEs of ferromagnets or noncollinear antiferromagnets. To highlight the unique nature and consequences of our mechanism, we introduce the term crystal Hall effect (CHE). On the example of the collinear antiferromagnet RuO2, we also illustrate that the crystal symmetry breaking mechanism is robust, leading to large magnitudes of the CHE.

While RuO2 has oxygen atoms on locally noncentrosymmetric sites, it is globally centrosymmetric. We analyze also the CHE in the quasi–two-dimensional (2D) antiferromagnet (17) CoNb3S6, which is globally noncentrosymmetric. We catalog all possible magnetic symmetries hosting the CHE in collinear antiferromagnets and a number of material candidates. Last, we discuss the relevance of the CHE for earlier inconclusive interpretations of Hall measurements (17, 21) in the abovementioned CoNb3S6 and in the Ce-doped canted antiferromagnet CaMnO3.

RESULTS

Crystal symmetry breaking mechanism in a collinear antiferromagnet

We now describe the T symmetry breaking due to the complex asymmetric magnetization density in collinear antiferromagnets, emphasizing the distinct nature of the CHE from the usual AHE mechanism. The anomalous Hall conductivity in IrMn3 and similar materials is generated by the symmetry lowering due to the nontrivial noncollinear antiferromagnetic order (6). The magnetization densities are locally highly symmetric as illustrated in Fig. 1C, and the T symmetry is broken in the MLG by the mutual noncollinearity of the spin-projection vectors on the magnetic sites. The Fermi surfaces exhibit noncollinear spin textures in the crystal momentum space, and spin is not a good quantum number even without SOC. Ir Wyckoff positions are centrosymmetric, and the MSG does not depend on their presence or absence in the IrMn3 crystal. This justifies neglecting the nonmagnetic atoms in this class of crystals and analyzing only the magnetic spin structure (see fig. S1) (6). The SOC lifts the degeneracy between two magnetic states connected by spin reversals and translates the symmetry breaking into the orbital sector, similarly as in the ferromagnetic AHE (6).

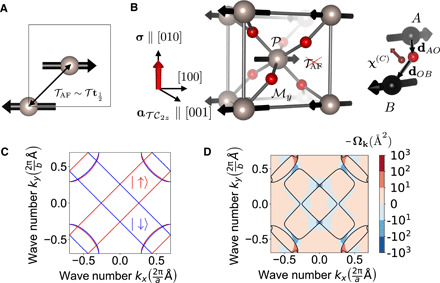

From this perspective, the two-site collinear antiferromagnet, as shown in Fig. 2A, is trivial since it cannot generate any Hall signal due to the symmetry. However, by interlacing the magnetic lattice by the nonmagnetic atoms distributed at noncentrosymmetric positions, we can break the symmetry, as we show in Fig. 1 (D and E) and in Fig. 2B on the rutile antiferromagnet RuO2. For the collinear antiferromagnetism with quantization axis along the [100] direction, the system acquires MSG Pn′n′m (type III), magnetic point group (MPG) m′m′m, and MLG 2′2′2. The symmetry generators are P glide mirror plane marked in Fig. 2B, and antiunitary rotation , and they do not change when we cant the perfectly antiparallel magnetic moments toward the [010] direction. This illustrates the ferromagnetic nature of the symmetry groups even in a fully compensated antiferromagnetic state with the Hall vector σ = (0, σxz,0).

Fig. 2. Crystal symmetry breaking, large spin-split Fermi surface, and Berry curvature in collinear antiferromagnet RuO2.

(A) Collinear antiferromagnet with effective time-reversal symmetry . (B) Left: The unit cell of antiferromagnetic RuO2 with the Néel vector along the [100] axis and marked crystal symmetries. Right: Detail of the generation of the local crystal chirality by noncentrosymmetric oxygen atoms . (C) Antiferromagnetic Fermi surface cut at wave vector kz = 0 calculated without spin-orbit coupling. The spin up and down projections are colored in red and blue. (D) Calculations with spin-orbit coupling of crystal momentum resolved Berry curvature Ωy(kx, ky,0) in atomic units.

In Fig. 2 (C and D), we illustrate the microscopic mechanism that generates a nonzero Berry curvature with collinear antiferromagnetism. In the nonmagnetic state, the bands are Kramers degenerate due to the P and T symmetries (19) of the rutile crystal. When we introduce the collinear antiferromagnetic order, the distribution of oxygen atoms deforms the magnetization densities around the Ru sublattices, as we show in Fig. 1E and in fig. S2. The magnetization density explicitly illustrates breaking of the symmetry for a generic crystal momentum k. However, the effective symmetry comprising rotating the magnetization densities (oxygen octahedra) by 90° around each Ru atom in combination with half-unit cell translation enforces the two Ru atoms to be in the antiferromagnetic spin state. In turn, the integrated even-in-magnetization quantities such as the density of states (DOS) when SOC is switched off remain perfectly compensated.

The energy bands are strongly spin split for a generic k, even when the relativistic SOC is switched off in the density functional theory (DFT) calculation (see red/blue-colored bands in Fig. 2C). In contrast to the noncollinear antiferromagnets, spin is a good quantum number here in the absence of SOC. When the relativistic corrections are switched on, the local noncetrosymmetricity also generates asymmetric SOC (ASOC) ∼ k × ∇ V · s, which additionally lowers the symmetry. The resulting band structure is locally spin polarized, spin mixed, and generates the required asymmetry between left and right moving electrons as can be seen on large Berry curvature hotspots around the additional spin splittings in Fermi surface bands shown in Fig. 2D. Note that the net moment generated by the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction (DMI) is known to be a relativistic effect of a small magnitude (22). In contrast, our calculations demonstrate that the spin-symmetry breaking is not a small correction but a strong effect reflected in large magnitudes of the CHE.

We calculate the intrinsic Hall conductivity (independent of disorder scattering) by integrating the Berry curvature, Ω(k) = − Im 〈∂ku(k) ∣ × ∣ ∂ku(k)〉, in the crystal momentum space (see Materials and Methods). In fig. S3, we show that the nonvanishing integral component ∫dkxΩy(k) is even in ky as we expect from the symmetry analysis, while the ℳy, P, and symmetries imply that ∫dkxΩx(k) = 0, and ℳy and yield ∫dkzΩz(k) = 0. We obtain σxz = 35.7 S cm−1, demonstrating a large crystal Hall conductivity in stoichiometric RuO2. The DFT calculations of the CHE are extensively discussed below.

Crystal chirality control of the Hall conductivity

We can illustrate the crystal chirality features on a simplified model of a collinear antiferromagnet with CHE. Inspired by the Haldane’s quantum AHE model (23), we have found a minimal Hamiltonian simultaneously hosting the staggered antiferromagnetic potential in combination with T symmetry breaking compatible with the existence of the Hall conductivity

| (2) |

Here, the first term describes electron hopping between nearest-neighbor magnetic sites i and j on a body center cubic lattice, and the second term describes on-site exchange field with an alternating direction on the neighboring sites, ui = − uj (s are spin Pauli matrices). These two terms represent a tight-binding model of a collinear antiferromagnet with the MLG T symmetry. We lower the symmetry of the Hamiltonian (Eq. 2) by a staggered ASOC term due to the local crystal chirality defined as

| (3) |

arising because of the nonmagnetic atoms at the noncentrosymmetric positions. Here, dAO and dOB are vectors connecting two nearest-neighbor Ru atoms with the common interlaced oxygen atom (cf. Fig. 2B), where in Eq. 2 marks the chirality unit vector.

While the exchange and ASOC in Eq. 2 separately do not break the T symmetry, their combination does break the MLG T symmetry. The model crystal momentum Hamiltonian can exhibit nodal-chain band topology (24) and a large Berry curvature along the [010] direction, which we discuss in detail in fig. S4. In contrast to the Haldane’s quantum anomalous Hall model, our model demonstrates the possibility of the spontaneous Hall conductivity without the necessity for ferromagnetism or complicated noncollinear and noncoplanar antiferromagnetism, even in a globally centrosymmetric system.

We now demonstrate the possibility to control the Hall conductivity sign by swapping the crystal chirality. In Fig. 3 (A and B), we show the RuO2 crystal with the two possible distributions of the oxygen atoms corresponding to the opposite crystal chiralities χ(C) = ± 1. While the MSG is the same in both cases, the local magnetization densities, obtained from the DFT calculations, are rotated by 90° (25). In Fig. 3C, we plot the energy bands corresponding to the crystal in Fig. 3A. The red and blue arrows mark spin up and down projection for the bands calculated without SOC. When we include the SOC, we obtain additional splittings of the bands and large Berry curvature, as we show in Figs. 2D and 3D. The red and blue colors correspond to the opposite local chirality crystals shown in Fig. 3 (A and B).

Fig. 3. Crystal chirality control of Hall conductivity sign.

(A and B) View along the tetragonal crystal axis on the RuO2 crystal with two possible configurations of nonmagnetic oxygen atoms. Redistribution of the oxygen atoms does not change the magnetic symmetry of the crystal; however, it changes the local crystal chirality orientation χ(C) and rotates, by 90∘, the shape of the magnetization density isosurfaces. (C) Calculated energy bands in the RuO2 antiferromagnet without spin-orbit coupling (red and blue bands correspond to the opposite spin projections) and with spin-orbit coupling (black bands). (D) The largest contribution to the Berry curvature Ω originates from the spin-split bands by the spin-orbit coupling. The red and blue color corresponds to the two opposite crystal chiralities χ(C) and demonstrates the expected Berry curvature sign change [compare to (A) and (B)].

The flipping of the sign of CHE σxz with the Néel vector reversal is consistent with the Onsager relations. The two crystals in Fig. 3 (A and B) can be mapped on each other by the T operation combined with a half-unit cell translation, and this symmetry ensures the same magnitude, while opposite sign, of σxz for the two crystal chiralities. We can see this also from our minimal model analysis, where σ changes sign when the chirality in the spin-orbit term is reversed. From this, we can draw a comparison to the AHE in ferromagnets and noncollinear antiferromagnets, where the sign reversal of the Hall conductivity is governed by the reversal of magnetic moments. The sign of the CHE in the simple collinear antiferromagnets such as RuO2 is, instead, determined by the sign of the dot product underlining the crystal mechanism of the symmetry breaking in this collinear antiferromagnet.

Crystal Hall phenomenology in RuO2

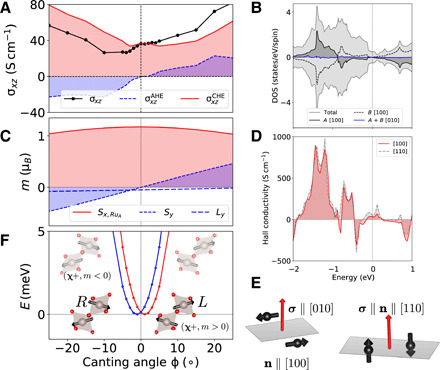

In Fig. 4A, we identify a sizable CHE conductivity in the room temperature collinear antiferromagnet RuO2 by our first-principle calculations. Note that among the rutile antiferromagnets (18), a metallic phase is rare, which makes the recently found (26, 27) itinerant antiferromagnetism in RuO2 exceptional within this family of simple collinear antiferromagnets. Our DFT calculations (see fig. S5) show that for a medium-strength Hubbard parameter (U ∼ 1 to 3 eV), antiferromagnetism and metallic DOS coexist, consistent with previous reports (26, 27). We set in all plots in the main text U∼ 2 eV, which reproduces best the experimental antiferromagnetic moments.

Fig. 4. First-principle calculation of sizeable and anisotropic crystal Hall effect in RuO2.

(A) First-principle calculation of the dependence on the canting angle of the Hall conductivity and its separation into the anomalous (ferromagnetic) and crystal (antiferromagnetic) parts. (B) Ru sublattice A (solid) and B (dashed) projected DOSs for the Néel vector along the [100] axis. Black solid and dotted lines show calculations with spin-orbit coupling of the DOS component for moments projected along the [100] axis. Blue line shows the sum of sublattice DOSs for the moment projection along the [010] axis, which corresponds to the small canting of the antiparallel moments due to the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. (C) The dependence on the canting angle of the spin component Sx (projected on single Ru sublattice A), Sy (total net spin moment), and orbital magnetization Ly. (D) Energy dependence of the calculated crystal Hall conductivity for n ∥ [100] (red solid line) and n ∥ [110] (gray dashed line). (E) The mutual orientation of the Néel vector n and Hall vector σ. (F) Two magnetic domains with opposite Néel vector induced by opposite field H and the corresponding energy costs for canting. H∥ [010] corresponds to canting angles ϕ > 0 and prefers n ∥ [100] (red) over (blue). In the inset, we depict four combinations of the local crystal chirality and Néel vector orientations. The two combinations marked L and R have the lowest energy.

When turning the sizable SOC off in our DFT calculation, we observe a perfect antiferromagnetic compensation in the Ru-projected DOS. With the large atomic SOC turned on, only minute corrections to the DOS occur, as shown in Fig. 4B. They result in a small net magnetic moment, m = mA + mB, of a magnitude ∼0.05 μB due to the DMI (22). Here, mA/B are magnetizations of the antiferromagnetic A and B sublattices. In comparison, the Néel vector n = (mA − mB)/2 has a magnitude ∼1.17 μB.

To gain further insight, we calculate the dependence of the CHE for n ∥ [100] on the canting angle between magnetizations of sublattices A and B (see Fig. 4A). Furthermore, we separate in Fig. 4A σxz into a contribution even in m

| (4) |

and odd in m

| (5) |

Here, corresponds to a contribution induced by the small net moment, analogous to the AHE in ferromagnets. We see that this term is roughly linear in m (see Fig. 4, A and C), at least for ∣ϕ∣<10∘, while is almost constant at small ϕ and dominates the contribution to σxz. Hence, the small net magnetic moment has a negligible effect on σxz. This is in notable contrast to the recently studied antiferromagnets GdPtBi (20) and EuTiO3 (28), which order in a T-invariant MLG and whose observed AHE is entirely due to the canting induced by an applied external magnetic field.

In Fig. 4D, we plot the intrinsic crystal Hall conductivity for the Néel vector orientation along [100] and [110] crystal axes as a function of the Fermi level position, which simulates, e.g., off-stoichiometry or alloying with other elements. For artificially constrained, perfectly antiparallel spin moments along the [100] axis, σ ∥ [010], and we obtain σxz = 36.4 S cm−1 for stoichiometric RuO2. For a canting angle ≈1∘ obtained from the DFT calculation, m ∥ [010] and σxz = 35.7 S cm−1. For the Néel vector along the [110] axis, σH = 54.6 S cm−1. These crystal Hall conductivities are comparable to the large anomalous Hall conductivities in noncollinear antiferromagnets Mn3Sn [100 S cm−1 in experiment (10) and 133 S cm−1 in theory (29)] or Mn3Pt [74 S cm−1 in experiment and 57 S cm−1 in theory (12)], and are much larger than the topological Hall conductivities in antiferromagnetic spin liquid candidates [<5 S cm−1 (13)]. For Fermi level shifts of ≈ − 0.5 eV, corresponding to a reduced filling by one electron in off-stoichiometric Ru1 + xO2 − x (see fig. S5F), the CHE conductivity can be as large as ∼300 S cm−1. At larger energy shifts (≈ − 1 eV), even ∼1000 S cm−1 is reached. This is similar to the record magnitudes reported for the AHE in ferromagnets or noncollinear antiferromagnets (see table S1) (2, 11).

The CHE can also show a large anisotropy in the Hall conductivity, which can be understood in terms of the symmetry imposed dependence of the hybridization of linear band crossings and of the gapping of nodal-line features (30) on the Néel vector orientation (see fig. S6) (19). For example, the MSG changes from Pnn′m′ for n ∥ [100] to Cnn′m′ for n ∥ [110].

In fig. S7 (C and D), we observe that DMI generates a small magnetization that is perpendicular to the Néel vector when n ∥ [100], while for n ∥ [110], it generates a small parallel magnetization. While in the former case the Hall vector is perpendicular to the Néel vector, in the latter case, the two vectors are parallel as we schematically illustrate in Fig. 4E. Also, from Fig. 4 (A and C) and fig. S7, we see that the crystal Hall conductivity is proportional to neither spin nor orbital magnetization, and for a generic angle of the Néel vector, the mutual orientation of the Néel and Hall vectors is arbitrary and depends on microscopic details.

Proposals for the experimental observation of the CHE

To measure the CHE in RuO2, we need to ensure one dominating crystal chirality (e.g., by growing single-domain samples) and the correct orientation of the Néel vector. Preferably, we suggest to orient the crystal growth direction along the Hall vector; two possibilities are marked in Fig. 4E. We note that the easy axis in RuO2 can point along the [001] direction [as experimentally observed in bulk (26) and consistent with our calculations for stoichiometric RuO2 shown in fig. S5] or slightly tilted from the [001] axis as reported for thin films (27).

Furthermore, the external magnetic field applied along the [001] axis can be used to help the moments tilt toward the (001) plane. We remark that the magnetic field magnitude can be substantially smaller than a spin-flop field that would switch the Néel vector fully into the (001) plane. This is because the crystal Hall conductivity is nonzero already for a small tilt of the Néel vector from the [001] direction. Alternatively, our DFT calculations show (see fig. S5) that by a few percent off-stoichiometry or alloying, e.g., in Ru1+xO2−x or Ru1−xIrxO2, the easy axis can be constrained to the (001) plane. With the Néel vector in the (001) plane, an in-plane magnetic field can be applied to select one of the two domains with opposite in-plane Néel vectors and corresponding opposite signs of the Hall effect, consistent with domain energies in Fig. 4F. This also demonstrates the possibility to turn the CHE on and off by reorienting the Néel vector. In contrast, the AHE in ferromagnets is allowed by symmetry for any direction of the magnetization. Note, however, that in general, the direction and magnitude of the Hall vector are also not proportional to the magnetic order parameter vector in ferromagnets (31).

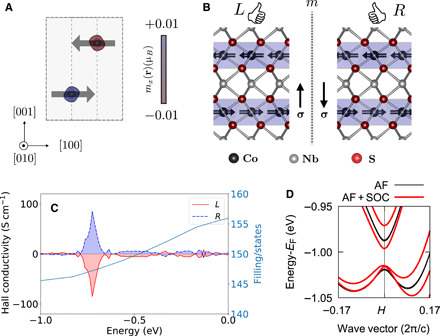

The sign of the Hall conductivity can be controlled also by the global crystal chirality. We explain this on the CoNb3S6 crystal (its low-symmetry magnetization isosurfaces are shown in Fig. 5A), a quasi-2D hexagonal collinear antiferromagnet derived from the Van der Waals crystal of transition metal dichalcogenide NbS2 (17). The opposite sign of crystal Hall conductivity, shown in Fig. 5 (B and C), corresponds to the two crystals with the opposite sense of the spatial inversion symmetry breaking, marked L and R in Fig. 5B.

Fig. 5. Crystal Hall conductivity in the chiral crystal of CoNb3S6 antiferromagnet.

(A) Calculated magnetization isosurfaces in the CoNb3S6 antiferromagnet exhibit low symmetry and illustrate the global chiral symmetry breaking. (B) The crystal of the CoNb3S6 antiferromagnet ("L, " with a left-handed chirality) and its mirror m image ("R, " with a right-handed chirality). Note that the mirror m maps the two chiralities onto each other by redistributing the nonmagnetic S atoms while preserving the magnetic atom positions and orientations of the collinear antiferromagnetic moments. (C) The calculated crystal Hall conductivity (left axis) changes sign when the crystal chirality is reversed from left- to right-handed. The right axis corresponds to the calculated dependence of the electron filling on energy. (D) Band structure detail of antiferromagnetic CoNb3S6 without (black line) and with (red line) spin-orbit coupling. We show fraction of the LHA path in Brillouin zone.

CoNb3S6, with collinear antiferromagnetic moments (32), has the C2′2′21 MSG and the same MLG as RuO2 (2′2′2), where the unprimed rotational axis C2 is perpendicular to the hexagonal layers and σ ∥ aC2 (according to our classification in Table 1). However, the global P symmetry breaking promotes the role of ASOC, as we show in Fig. 5D, where the bands are split along the high-symmetry axes, not only at high-symmetry points (see details of the energy bands in fig. S8). The energy bands, e.g., around the H point, are substantially split by the ASOC, and in combination with collinear antiferromagnetism, a large Berry curvature Ωz is generated as we illustrate in fig. S8 on the Berry curvature summed up to the lowest energy band shown in Fig. 5D. The Berry curvature appears to be concentrated around these antiferromagnetic generalizations of Kramers-Weyl–like dispersions (33).

Table 1. Catalog of Hall vector admissible magnetic point groups in collinear antiferromagnets and selected material candidates.

First two rows list type I, and last two rows type III magnetic point groups (MPGs), respectively. We list more material candidates and all magnetic symmetries allowing any Hall signal in table S2. If not referenced otherwise, the material candidate was obtained from the MAGNDATA database (34). MLG marks the magnetic Laue group.

We note that the spontaneous Hall effect recently detected in CoNb3S6 (17) could not be reconciled with a collinear antiferromagnetic order inferred from neutron scattering (32). Our first-principles calculations shown in Fig. 5C give a magnitude of the CHE in hole-doped (Fermi energy ∼ − 0.7 eV) CoNb3S6, which is consistent with the experimental value for this doping level [27 S cm−1; (17)].

DISCUSSION

While the symmetry allowed direction of the Hall vector σ depends only on the MLG, the possibility to control the sign of the CHE by the local or global crystal chirality depends on the full MPG. To enumerate all possible symmetries allowing for the CHE in collinear antiferromagnets, we start by excluding antiferromagnetic symmetries incompatible with the existence of a Hall vector. Among those are all MSG type IV antiferromagnets with symmetry ( is half-unit cell translation as, e.g., in GdPtBi), and MSG type III antiferromagnets symmetry (e.g., CuMnAs, or Mn2Au), which have the T symmetry in the MLG. In total, 275 MSGs, 31 MPGs, and 10 MLGs of types I and III remain as candidates for spontaneous Hall effects. However, simple collinear antiferromagnetism is not compatible with three-, four-, and sixfold rotational symmetries. We summarize in Table 1 the remaining 12 MPGs and 4 MLGs that may host the CHE in collinear antiferromagnets.

We can formulate simple rules allowing for a fast determination of the orientation of the Hall vector σ based on the existence of these only four MLGs. (i) In MLG 1, the orientation of σ is arbitrary and depends on microscopic details of the electronic structure. (ii) In systems with 2′ rotational axis, the Hall vector is perpendicular to the axis, and the orientation within this plane is set microscopically. (iii) The twofold rotational axis constrains the Hall vector to be parallel to this axis (see Figs. 1A and 5B), and the orientation of the Hall vector is determined uniquely by the symmetry. All the remaining possibilities can be derived from these three cases (for instance, in 2′2′2, the Hall vector is perpendicular to both 2′ and parallel to 2).

We point out that as many as ∼10% of the total of ∼700 magnetic structures reported in the Bilbao MAGNDATA database (34) belong to the class of collinear antiferromagnets in which the CHE is allowed by symmetry. We point out that our CHE mechanism will materialize in these candidates possibly also in its optical or thermal variants (35). In Table 1, we list some additional material candidate examples such as orthoferrites, perovskites, or corundum structure materials. In addition, we provide in the Supplementary Materials a classification table (table S2) of all 31 MPGs allowing for Hall effects also in noncollinear spin structures.

The CHE might also contribute to Hall signals, which were earlier taken as a signature of nontrivial and topological magnetization textures. This applies, e.g., to the measured spontaneous Hall signal in a Ce-doped canted antiferromagnet CaMnO3 (MPG 2′/m′) (21). Apart from the AHE contribution due to the net magnetic moment, our symmetry analysis shows that the CHE associated with the Néel vector, rather than the canting moment (cf. Fig. 4, A and C), is allowed in this material due to the oxygen noncentrosymmetric positions. The spikes arising in the Hall signal by applying a magnetic field can be alternatively explained as a convolution of two spontaneous Hall signals from material regions with the opposite Hall sign (36). These two regions might correspond to the two crystallites with the opposite sign of the CHE. Furthermore, methods for growing single-crystal chirality systems (37) can be used to enhance the Hall signal.

Last, we remark that existing mechanisms of the quantum spontaneous Hall effect rely either on rare ferromagnetic insulators or on fragile diluted magnetic topological insulators with low critical temperatures and small magnetic band gaps (38). Our crystal spontaneous symmetry breaking represents a long-sought mechanism marrying strong Hall response with a robust room temperature intrinsic collinear antiferromagnetism (35).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Model Hamiltonian

The Hamiltonian of our model (2) in the crystal momentum space reads

| (6) |

where τ are site Pauli matrices and .

Magnetic symmetry groups of studied antiferromagnets

The MSG of rutile antiferromagnets for the Néel vector along the [100] and [110] axes, respectively, are

where the nonsymmorphic symmetries are the unitary glide plane , screw rotation , and antiunitary and , and in the case of Cmm′m′, there are also operations coupled by t = (1/2,1/2,0).

The MSG (and the corresponding MPG 4′/mm′m) of rutile antiferromagnets for the Néel vector along the [001] prohibits the existence of the Hall vector.

The MSG of CoNb3S6 for the Néel vector along the [100] axis is C2′2′21 and includes symmetry operations , and , where t = (0,0,1/2) and all the symmetries coupled by t = (1/2,1/2,0). The MLG (MPG stripped off inversions) is the same, 2′2′2, for both RuO2 and CoNb3S6 crystals, and thus, also the shape of the conductivity tensor is the same.

Berry curvature

The time reversal operation acts on the Berry curvature as TΩ(k) = − Ω( − k), and the following symmetries operate as

We calculated the Hall conductivity in our model and in DFT as

| (7) |

where the Berry curvature, Ωy(n, k), is defined as in the main text for each individual band with the quantum number n and corresponding Bloch functions un(k), and f(k) is the Fermi-Dirac distribution.

The presented Hall conductivities were calculated at zero temperature. In fig. S7, we show that introducing a spectral broadening of up to 10 meV (corresponding approximately to the experimental conductivity at room temperature) has negligible influence on the calculated CHE.

DFT calculations

We have calculated the electronic structure of RuO2 in the pseudopotential DFT code Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) (39), within Perdew–Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) + U + SOC (a spherically invariant version of DFT + U) on a 12 × 12 × 16 k-point grid, and we used an energy cutoff of 500 eV. In the case of the RuO2 crystal, we performed our magnetocrystalline anisotropy calculations on a 16 × 16 × 24 k-point grid. We obtained Wannier functions on a 12 × 12 × 16 grid using the Wannier90 code (40), and we calculated the Hall conductivity by using Eq. 7 evaluated on the Monkhorst-Pack grid with a 3213 crystal momentum integration mesh in Wannier tools (41). In the case of CoNb3S6, we evaluate Wannier functions on a 12 × 12 × 6 grid, and we use 2412 × 201 crystal momentum points for the Hall conductivity calculation. We tested our first-principles calculation methodology on the experimentally and theoretically investigated anomalous Hall conductivity in ferromagnets and noncollinear antiferromagnets, and we obtained an agreement with the previous reports [e.g., 234 S cm−1 in IrMn3; cf. (8)].

The distortion of the tetragonal unit cell (used in calculations with the Néel vector along the [100] axis), with lattice parameters a = 4.528, b = 4.536, c = 3.124Å, due to the magnetoelastic coupling does not change magnetic symmetries, and we use in the main text a tetragonal unit cell. For n ∥ [110] and [001] we obtained from our DFT calculations after relaxation: a = b = 4.5337, c = 3.124Å, and a = b = 4.5331, c = 3.1241Å, respectively, consistent with a previous report (26).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge discussions with M. Kläui, M. Jourdan, G. Jakob, J. Železný, Y. Mokrousov, and S. Stemmer. Funding: We acknowledge the use of the supercomputer MOGON at JGU (http://hpc.uni-mainz.de), the computing and storage facilities owned by parties and projects contributing to the National Grid Infrastructure MetaCentrum provided under the programme “Projects of Projects of Large Research, Development, and Innovations Infrastructures” (CESNET LM2015042) and support from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, the Transregional Collaborative Research Center (SFB/TRR) 173 SPIN+X, the Ministry of Education of the Czech Republic Grants LM2015087 and LNSM-LNSpin, EU FET Open RIA grant no. 766566, the Grant Agency of the Charles University grant no. 280815, and the Czech Science Foundation grant no. 19-28375X. Author contributions: L.S. conceived the work. L.S. and R.G.-H. performed calculations. L.S., R.G.-H., T.J., and J.S. analyzed the results. L.S., T.J., and J.S. cowrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/23/eaaz8809/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Hall E. H., On a new action of the magnet on electric currents. Am. J. Math. 2, 287–292 (1879). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagaosa N., Sinova J., Onoda S., MacDonald A. H., Ong N. P., Anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1539–1592 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shtrikman S., Thomas H., Remarks on linear magneto-resistance and magneto-heat-conductivity. Solid State Commun. 3, 147–150 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleiner W. H., Space-time symmetry of transport coefficients. Phys. Rev. 142, 318–326 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seemann M., Ködderitzsch D., Wimmer S., Ebert H., Symmetry-imposed shape of linear response tensors. Phys. Rev. B 92, 155138 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki M.-T., Koretsune T., Ochi M., Arita R., Cluster multipole theory for anomalous Hall effect in antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 95, 094406 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grimmer H., General relations for transport properties in magnetically ordered crystals. Acta Crystallogr. A 49, 763–771 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H., Niu Q., Macdonald A. H., Anomalous Hall effect arising from noncollinear antiferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 017205 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kübler J., Felser C., Non-collinear antiferromagnets and the anomalous Hall effect. Europhys. Lett. 108, 67001 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakatsuji S., Kiyohara N., Higo T., Large anomalous Hall effect in a non-collinear antiferromagnet at room temperature. Nature 527, 212–215 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nayak A. K., Fischer J. E., Sun Y., Yan B., Karel J., Komarek A. C., Shekhar C., Kumar N., Schnelle W., Kübler J., Felser C., Parkin S. S. P., Large anomalous Hall effect driven by a nonvanishing Berry curvature in the noncolinear antiferromagnet Mn3Ge. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501870 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z. Q., Chen H., Wang J. M., Liu J. H., Wang K., Feng Z. X., Yan H., Wang X. R., Jiang C. B., Coey J. M. D., MacDonald A. H., Electrical switching of the topological anomalous Hall effect in a non-collinear antiferromagnet above room temperature. Nat. Electron. 1, 172–177 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacHida Y., Nakatsuji S., Onoda S., Tayama T., Sakakibara T., Time-reversal symmetry breaking and spontaneous Hall effect without magnetic dipole order. Nature 463, 210–213 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shindou R., Nagaosa N., Orbital ferromagnetism and anomalous Hall effect in antiferromagnets on the distorted fcc lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 116801 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagaosa N., Tokura Y., Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 899–911 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sürgers C., Fischer G., Winkel P., Löhneysen H. V., Large topological Hall effect in the non-collinear phase of an antiferromagnet. Nat. Commun. 5, 3400 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghimire N. J., Botana A. S., Jiang J. S., Zhang J., Chen Y.-S., Mitchell J. F., Large anomalous Hall effect in the chiral-lattice antiferromagnet CoNb3S6. Nat. Commun. 9, 3280 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.C. Bradley, A. Cracknell, The Mathematical Theory of Symmetry in Solids: Representation Theory for Point Groups and Space Groups (Clarendon Press, 1972). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Šmejkal L., Železný J., Sinova J., Jungwirth T., Electric control of Dirac quasiparticles by spin-orbit torque in an antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 106402 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki T., Chisnell R., Devarakonda A., Liu Y.-T., Feng W., Xiao D., Lynn J. W., Checkelsky J. G., Large anomalous Hall effect in a half-Heusler antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 12, 1119–1123 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vistoli L., Wang W., Sander A., Zhu Q., Casals B., Cichelero R., Barthélémy A., Fusil S., Herranz G., Valencia S., Abrudan R., Weschke E., Nakazawa K., Kohno H., Santamaria J., Wu W., Garcia V., Bibes M., Giant topological Hall effect in correlated oxide thin films. Nat. Phys. 15, 67–72 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kzyaloshinskii I. E., The magnetic structure of fluorides of the transition metals. Sov. Phys. JETP 6, 1120–1122 (1958). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haldane F. D. M., Model for a quantum hall effect without landau levels: Condensed-matter realization of the “parity anomaly”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2015 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bzdušek T., Wu Q., Rüegg A., Sigrist M., Soluyanov A. A., Nodal-chain metals. Nature 538, 75–78 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gopalan V., Litvin D. B., Rotation-reversal symmetries in crystals and handed structures. Nat. Mater. 10, 376–381 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berlijn T., Snijders P. C., Delaire O., Zhou H.-D., Maier T. A., Cao H.-B., Chi S.-X., Matsuda M., Wang Y., Koehler M. R., Kent P. R. C., Weitering H. H., Itinerant antiferromagnetism in RuO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 077201 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu Z. H., Strempfer J., Rao R. R., Occhialini C. A., Pelliciari J., Choi Y., Kawaguchi T., You H., Shao-Horn Y., Comin R., Anomalous antiferromagnetism in metallic RuO2 determined by resonant x-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 017202 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi K. S., Ishizuka H., Murata T., Wang Q. Y., Tokura Y., Nagaosa N., Kawasaki M., Anomalous Hall effect derived from multiple Weyl nodes in high-mobility EuTiO3 films. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar7880 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y., Sun Y., Yang H., Železný J., Parkin S. P. P., Felser C., Yan B., Strong anisotropic anomalous Hall effect and spin Hall effect in the chiral antiferromagnetic compounds Mn3X (X = Ge, Sn, Ga, Ir, Rh, and Pt). Phys. Rev. B 95, 075128 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim K., Seo J., Lee E., Ko K.-T., Kim B. S., Jang B. G., Ok J. M., Lee J., Jo Y. J., Kang W., Shim J. H., Kim C., Yeom H. W., Il Min B., Yang B.-J., Kim J. S., Large anomalous Hall current induced by topological nodal lines in a ferromagnetic van der Waals semimetal. Nat. Mater. 17, 794–799 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roman E., Mokrousov Y., Souza I., Orientation dependence of the intrinsic anomalous hall effect in hcp cobalt. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 097203 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parkin S. S. P., Marseglia E. A., Brown P. J., Magnetic structure of Co1/3 NbS2 and Co1/3 TaS2. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 16, 2765–2778 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang G., Wieder B. J., Schindler F., Sanchez D. S., Belopolski I., Huang S.-M., Singh B., Wu D., Chang T.-R., Neupert T., Xu S.-Y., Lin H., Hasan M. Z., Topological quantum properties of chiral crystals. Nat. Mater. 17, 978–985 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallego S. V., Perez-Mato J. M., Elcoro L., Tasci E. S., Hanson R. M., Aroyo M. I., Madariaga G., MAGNDATA: Towards a database of magnetic structures. II. The incommensurate case. J. Appl. Cryst. 49, 1941–1956 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Šmejkal L., Mokrousov Y., Yan B., MacDonald A. H., Topological antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Phys. 14, 242–251 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerber A., Interpretation of experimental evidence of the topological hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 98, 214440 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Banerjee-Ghosh K., Ben Dor O., Tassinari F., Capua E., Yochelis S., Capua A., Yang S.-H., Parkin S. S. P., Sarkar S., Kronik L., Baczewski L. T., Naaman R., Paltiel Y., Separation of enantiomers by their enantiospecific interaction with achiral magnetic substrates. Science 360, 1331–1334 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tokura Y., Yasuda K., Tsukazaki A., Magnetic topological insulators. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 126–143 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kresse G., Furthmüller J., Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mostofi A. A., Yates J. R., Pizzi G., Lee Y.-S., Souza I., Vanderbilt D., Marzari N., An updated version of wannier90: A tool for obtaining maximally-localised Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 2309–2310 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu Q., Zhang S., Song H.-F., Troyer M., Soluyanov A. A., Wanniertools : An open-source software package for novel topological materials. Comput. Phys. Commun. 224, 405–416 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao Y., Kleinman L., MacDonald A. H., Sinova J., Jungwirth T., Wang D.-s., Wang E., Niu Q., First principles calculation of anomalous Hall conductivity in ferromagnetic bcc Fe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 037204 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu E., Sun Y., Kumar N., Muechler L., Sun A., Jiao L., Yang S.-Y., Liu D., Liang A., Xu Q., Kroder J., Süß V., Borrmann H., Shekhar C., Wang Z., Xi C., Wang W., Schnelle W., Wirth S., Chen Y., Goennenwein S. T. B., Felser C., Giant anomalous Hall effect in a ferromagnetic kagomé-lattice semimetal. Nat. Phys. 14, 1125–1131 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Železný J., Zhang Y., Felser C., Yan B., Spin-polarized current in noncollinear antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 187204 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryden W. D., Lawson A. W., Sartain C. C., Electrical transport properties of IrO2 and RuO2. Phys. Rev. B 1, 1494–1500 (1970). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/23/eaaz8809/DC1