Abstract

BACKGROUND

A watch-and-wait strategy is a nonoperative alternative to sphincter-preserving surgery for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who achieve a clinical complete response after neoadjuvant therapy. There are limited data about bowel function for patients undergoing this organ-preservation approach.

OBJECTIVE

To compare bowel function in patients with rectal cancer managed with a watch-and-wait approach to bowel function in patients who underwent sphincter-preserving surgery (total mesorectal excision).

DESIGN

Retrospective case-control study employing patient-reported outcomes.

SETTING

Comprehensive cancer center.

PATIENTS

Twenty-one patients underwent a watch-and-wait approach and were matched 1:1 with 21 patients from a pool of 190 patients who underwent sphincter-preserving surgery, based on age, gender, and tumor distance from the anal verge.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Bowel function using the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Bowel Function Instrument.

RESULTS

Patients in the watch-and-wait arm had better bowel function on the overall scale (median total score, 76 vs 55; p < 0.001) and on all subscales, with the greatest difference on the urgency/soilage subscale (median score, 20 vs 12; p < 0.001).

LIMITATIONS

Retrospective design, small sample size, and temporal variability between surgery and time of questionnaire completion.

CONCLUSIONS

A watch-and-wait strategy correlated with overall better bowel function when compared to sphincter-preserving surgery using a comprehensive validated bowel dysfunction tool. See Video Abstract.

Keywords: Colorectal surgery, Patient-reported outcomes, Rectal cancer, Watch-and wait strategy

INTRODUCTION

In patients with locally advanced rectal cancer, neoadjuvant therapy (NAT) and sphincter-preserving total mesorectal excision (SPTME) provide excellent local control and survival.1 However, the combination of the two treatments is associated with significant bowel dysfunction, which can potentially affect the patient’s quality of life permanently.2 Anorectal dysfunction after NAT and SPTME has been well documented,3,4 with multiple contributing factors, including malfunction of the internal anal sphincter,5 decrease in anal canal sensation,6 loss of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex,7 and reduction in rectal reservoir compliance and capacity.8

Based on favorable retrospective data relative to oncologic outcomes, watch-and-wait (WW) protocols aimed at organ preservation have been advocated for the 10% to 40% of patients with rectal cancer who have no clinically detectable tumor in the rectum after NAT, i.e., those who have achieved a clinical complete response.9–11 In addition to these promising oncological results, the interest in patient-reported outcomes for patients managed with a WW approach has grown. Rectal cancer patients are greatly concerned about functional outcomes and long-term quality of life after treatment. This is reflected in a recent publication by Wrenn et al12 that described that the most important priorities for patients after favorable oncologic outcomes included avoidance of a stoma and/or the development of any surgical complications. Organ-preservation alternatives may help avoid these issues.

Data on comparison of bowel function between WW patients and SPTME patients are lacking. A previous study13 found that up to one-third of patients managed with a WW strategy had impaired bowel function according to the validated LARS (low anterior resection syndrome) score and EORTC-CR38,14,15 with significantly higher Vaizey scores on fecal incontinence in SPTME patients.16 However, it should be noted that these scoring systems may be limited in the ability to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the multidimensional impact on bowel function.

Therefore, our case-control study was aimed at comparing patient-reported bowel function between these two groups using a more comprehensive questionnaire—the Memorial Sloan Kettering Bowel Function Instrument (MSK BFI).

METHODS

Patient Selection

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK), and a waiver of informed consent was obtained. We retrospectively identified patients with rectal cancer who were managed with WW or underwent SPTME at MSK between November 1, 2011, and August 31, 2017. We excluded patients with a history of fecal incontinence, inflammatory bowel disease, stage IV disease, or patients with missing data. Patients who underwent SPTME were excluded if they had an extended rectal resection (i.e. resection beyond the standard plane of TME, involving adjacent pelvic organs, pelvic exenteration, or lateral pelvic sidewall dissection), an anastomotic leak, and/or a pelvic abscess.

NAT was either (i) chemoradiotherapy only, with a total dose of 5600 cGy in 28 fractions over a 5- to 6-week period and concomitant use of a sensitizing chemotherapeutic agent (fluorouracil or capecitabine) or (ii) total neoadjuvant therapy, consisting of 8 cycles of induction FOLFOX (leucovorin, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin) or 16 weeks of capecitabine-oxaliplatin followed by chemoradiotherapy, as previously described.17

All WW patients had a clinical complete response, defined as the absence of a clinically detectable primary tumor after NAT according to the MSK criteria18: (i) a flat white scar with telangiectasia and no ulcer or nodularity, (ii) a dark T2 signal with no visible lymph nodes on MRI, and (iii) no visible tumor on diffusion-weighted MRI. Controls were identified among 190 SPTME patients and were matched 1:1 using the variables age (<50, 51–65, and >65 years), sex (male and female), and distance of the tumor from the anal verge (±5 cm).

TME was performed using a standard open or minimally invasive approach (depending on the surgeon’s preference), usually 8 to 12 weeks after completion of NAT. A straight end-to-end colorectal or coloanal anastomosis was performed using either the hand-sewing or double-stapling technique depending on tumor location. A temporary diverting loop ileostomy was created depending on tumor location, patient characteristics, and the surgeon’s judgment.

MSK BFI

The MSK BFI questionnaire was specifically designed to assess bowel function after SPTME for rectal cancer19 and is the most comprehensive of such questionnaires currently in use.20 It consists of 18 questions recalling a 4-week time frame. Fourteen questions are grouped into three subscales—diet, urgency/soilage, and frequency—and four separate questions are added to obtain a total score ranging from 18 to 90, with a 90-point score corresponding to best possible bowel function. The MSK BFI total score is obtained using a linear scale and equal-weighting scoring system in which each question has five possible answer options ranging from “never” to “always”, except for one question which asks about the number of bowel movements per 24 hours. The instrument was designed on the basis of an extensive literature review, expert and patient input from semi-structured interviews, and factor analysis of clinically relevant variables, allowing a comprehensive and detailed evaluation of bowel function after SPTME. The main strength of this questionnaire is based on the meticulous design and comprehensive evaluation of bowel dysfunction after TME, as well as the correlation with clinically significant variables and quality of life instruments, all of these reflected in the scoring system.

Patients prospectively completed the MSK BFI questionnaire as part of standard clinical care, using a previously validated Web-based system.21 We compared the scores from the first questionnaire completed after the end of NAT in the WW patients with the scores from the first questionnaire completed after restoration of bowel continuity in the SPTME patients.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables, and medians and ranges were calculated for continuous variables. To compare the treatment groups, the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. Patients with missing data were excluded from analysis. The manuscript was prepared in accordance with STROBE guidelines.22

RESULTS

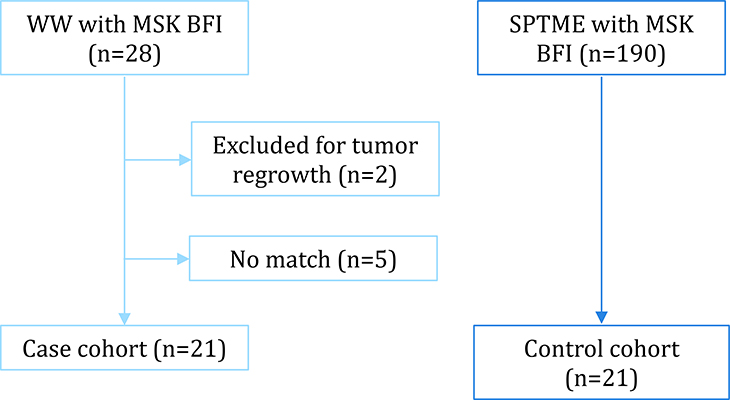

Of the 28 initially identified patients managed with a WW strategy with MSK BFI data available, 2 were excluded because of tumor regrowth and 5 because no proper matching control was found. The remaining 21 patients constituted the WW group (Figure 1). The WW patients did not differ significantly from the matched SPTME group in terms of demographic or clinical variables (Table 1). Patients in the WW group completed their first MSK BFI questionnaire at a median 5 months (range, 1 to 77 months) after NAT completion; patients in the SPTME group completed their first MSK BFI questionnaire at a median 5 months (range, 4 to 37 months) from restoration of bowel continuity (p = 0.62).

Figure 1.

Patient cohorts. WW = watch and wait; SPTME = sphincter-preserving total mesorectal excision; MSK BFI = Memorial Sloan Kettering Bowel Function Instrument.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | WW (n=21) | SPTME (n=21) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 68 (45–92) | 66 (44–73) | 0.27 |

| Sex, n (%) | 1 | ||

| Men | 10 (48) | 11 (52) | |

| Women | 11 (52) | 10 (48) | |

| Median tumor distance from anal verge, cm (range) | 6.5 (3–12) | 8 (3–13) | 0.09 |

| AJCC clinical stage, n (%) | 0.54 | ||

| I | 1 (5) | 0 | |

| II | 7 (33) | 6 (29) | |

| III | 13 (62) | 15 (71) | |

| Neoadjuvant therapy, n (%) | 0.12 | ||

| Chemoradiotherapy | 6 (29) | 2 (10) | |

| Total neoadjuvant therapy | 15 (71) | 19 (90) | |

| Anastomosis, n (%) | |||

| Stapled | 19 (90) | ||

| Hand-sewn* | 2 (10) | ||

| Temporary loop ileostomy, n (%) | 19 (90) | ||

| AJCC pathological stage, n (%) | |||

| pCR | 8 (38) | ||

| I | 6 (29) | ||

| II | 2 (10) | ||

| III | 5 (24) |

WW, watch and wait; SPTME, sphincter-preserving total mesorectal excision; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; pCR, pathological complete response

Includes one partial intersphincteric resection.

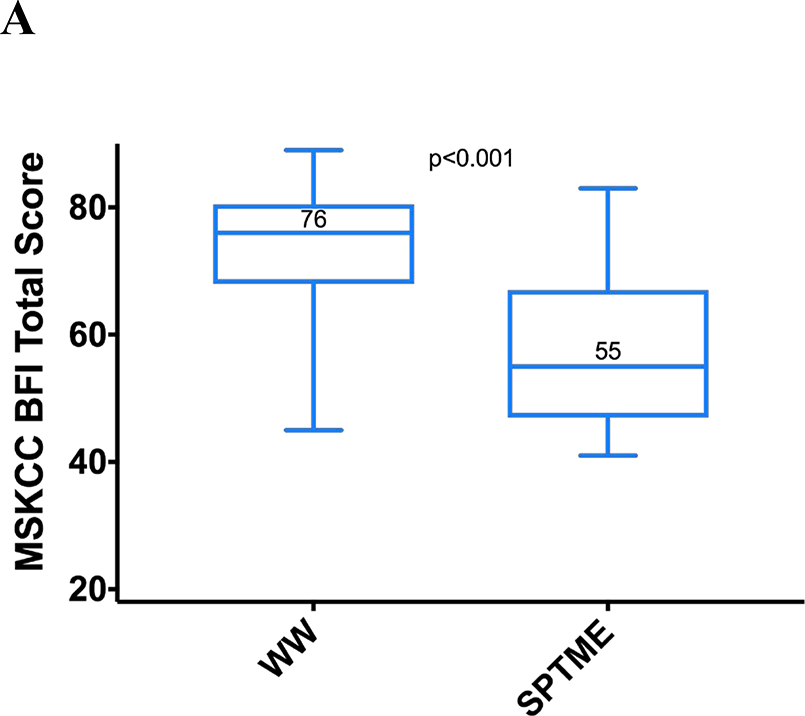

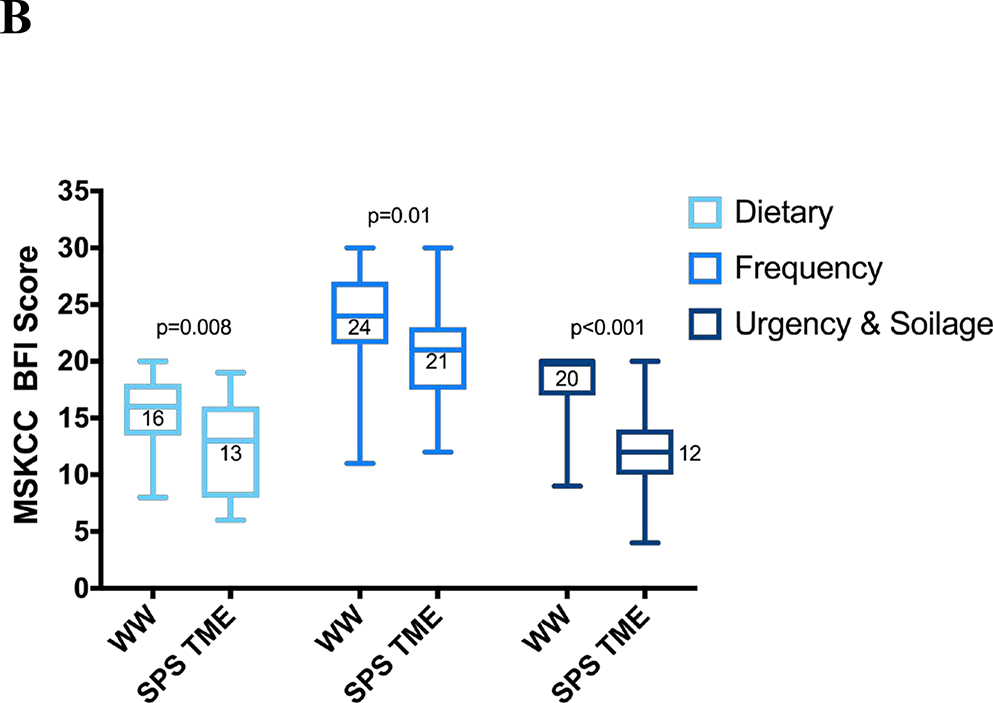

MSK BFI total scores were significantly higher in the WW group (median, 76 vs 55; p < 0.001), as were all the subscale scores (Figure 2). The greatest differences were on the urgency/soilage subscale (median score, 20 vs. 12; p < 0.001), with better scores in the WW group on each of the four subscale questions.

Figure 2.

MSK BFI scores with interquartile and full ranges (n = 21 for each group). (A) Total scores; (B) subscale scores. MSK BFI = Memorial Sloan Kettering Bowel Function Instrument; WW = watch and wait; SPTME = sphincter-preserving total mesorectal excision.

On the bowel frequency subscale, patients in the WW group had a median score of 24, compared with 21 for those in the SPTME group (p = 0.01), with patients in the former group reporting less frequent bowel movements (median bowel movements/24 hours, 2 vs 5, respectively; p = 0.002). On the diet subscale, patients in the WW group had a median score of 16, compared with 13 for those in the SPTME group (p = 0.008), mostly due to the dietary restrictions and reports of certain solid foods increasing the daily frequency of bowel movements in the SPTME group. The WW group also reported fewer episodes of incomplete evacuation, less clustering, and better control of flatus.

DISCUSSION

The findings of our study, which employed a comprehensive tool to assess patient-reported outcomes related to bowel function, indicate that after undergoing NAT, patients managed with a WW strategy have considerably better bowel function than those who undergo SPTME. Better bowel function was noted in both the overall and the specific dimensions of patient-reported bowel function as measured by the MSK BFI. In addition, our study found that patients in the WW group needed fewer modifications in their regular diet, were less likely to experience clustering, and had fewer episodes of incomplete evacuation than those in the SPTME group, suggesting better bowel function in the WW group.

Chemoradiotherapy in addition to total mesorectal excision is associated with worse bowel function in rectal cancer patients.2 However, there is no clarity about bowel function in patients who undergo a WW strategy after NAT.

Our results showed that the most marked differences between our study groups were on the urgency/soilage subscale, the dimension of bowel function most commonly affected after SPTME, as determined by other validated measures such as the LARS scoring system.14 Interestingly, the scores on the MSK BFI diet subscale—a dimension of bowel function not measured by other questionnaires such as the LARS score—were also better in the WW group.

Our findings on fecal incontinence are consistent with those of Habr-Gama et al,23 who reported better scores on the Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Index24 for patients managed with a WW strategy compared with those who underwent a transanal local excision. However, this study focused on anal incontinence only, which limits its ability to evaluate the full spectrum of symptoms of LARS. There was also no comparison group of patients who had undergone SPTME. In a recent cross-match study evaluating multiple areas of quality of life in patients managed with a WW approach, Hupkens et al13 found that one-third of the patients had major LARS, as determined with the LARS scoring system. The authors stated that the higher rate of major LARS may be attributable to the long-term morbidity associated with pelvic radiotherapy administered as part of NAT. We believe that several other factors may have influenced their findings. In comparison with the MSK BFI, the LARS scoring system does not provide a comprehensive assessment of LARS,20 showing that it may serve better as a screening tool rather than a focused evaluation of multiple dimensions that are altered after SPTME. Additionally, a recent study by Juul et al25 found that in a healthy population of people between the ages of 50 and 79 years, 9% of men and 19% of women had major LARS syndrome, which should be taken into consideration when discussing the effects of therapies on bowel function in rectal cancer patients. Nonetheless, neoadjuvant radiotherapy seems to exert a detrimental effect on bowel function in patients who undergo rectal preservation, according to previous literature.26

There is controversy about which patients are the optimal control group for WW patients. Since patients with an incomplete clinical response to NAT may never be offered nonoperative management,27 the clinical relevance of post-treatment bowel function in WW patients to patients who have an incomplete response may be limited. Nevertheless, we believe that the risk of bowel dysfunction is associated more with the distance of the rectal remnant (i.e. distance of the colorectal anastomosis) and radiation therapy than with tumor response to neoadjuvant therapy. Although our sample size was small, it is interesting to note that 38% of the SPTME control group in our study achieved a pathological complete response, and we did not observe significant differences between their MSK BFI total scores and the scores of patients with incomplete pathological response.

The limitations of our study include its small sample size and observational design. WW patients were selected from a retrospective database for clinical care of rectal cancer patients and not from a protocol-based WW data registry. This may have led to the possibility of selection bias, as the total potential number of patients who responded to the questionnaire is unknown. For the same reason, we cannot determine the true impact of potential selection bias in the control group. To reduce the limitations associated with selection bias, we cross-matched patients on variables most associated with poor bowel function after SPTME.28 This methodology led to the exclusion of 5 potentially eligible WW patients, for whom we were not able to find matching controls of similar age with similar tumor distance from the anal verge who received similar neoadjuvant treatment. Selection bias could have been introduced in this manner, considering that WW patients in retrospective series tend to be older and to have tumors closer to the sphincter29—variables that may be related to worse bowel function. It should be noted that only two patients in the SPSTME group underwent a hand-sewn anastomosis; one of the two patients underwent a partial intersphincteric resection. Analyses excluding these two patients produced similar results. Finally, because the MSK BFI questionnaire was not administered in a protocolized timeframe for all patients, the time intervals of the data make it difficult to externally validate our findings. An exploratory subgroup analysis of the effect of the time interval was performed, but due to the small sample size, a formal analysis was not feasible. Of note, similar results were obtained for patients who completed the questionnaire within 1 year of treatment and patients who completed the questionnaire more than 1 year after treatment.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our study is the first comprehensive evaluation of patient-reported bowel function in patients managed with a WW strategy using a validated instrument whose design is particularly well suited to assess the potential impact of an organ-preservation strategy.

CONCLUSIONS

A WW strategy is associated with overall better patient-reported bowel function compared to sphincter-preserving surgery, as determined with the MSK BFI questionnaire, which is the most comprehensive, validated bowel dysfunction measurement tool available. Our finding that WW patients may have better bowel function than SPTME patients should be interpreted with caution, due to the fact that no surgical complication was taken in consideration and most of the patients had a low risk of sphincter damage by radiation and/or surgery. Short- and long-term bowel dysfunction in WW patients needs to be further investigated in prospective trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was funded in part by the NCI grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Garcia-Aguilar has received support from Medtronic, Johnson and Johnson, and Intuitive Surgical. Dr. Pappou and Smith have received travel support for fellowship education from Intuitive Surgical. Dr. Smith has served as a clinical advisor for Guardant Health, Inc. The other authors have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Monson JRT, Weiser MR, Buie WD, et al. ; Standards Practice Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Practice parameters for the management of rectal cancer (revised). Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:535–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bregendahl S, Emmertsen KJ, Lous J, Laurberg S. Bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection with and without neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer: a population-based cross-sectional study. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pedersen IK, Christiansen J, Hint K, Jensen P, Olsen J, Mortensen PE. Anorectal function after low anterior resection for carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1986;204:133–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasmussen OO, Petersen IK, Christiansen J. Anorectal function following low anterior resection. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farouk R, Duthie GS, Lee PW, Monson JR. Endosonographic evidence of injury to the internal anal sphincter after low anterior resection: long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:888–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karanjia ND, Schache DJ, Heald RJ. Function of the distal rectum after low anterior resection for carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1992;79:114–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Efthimiadis C, Basdanis G, Zatagias A, et al. Manometric and clinical evaluation of patients after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8(suppl 1):s205–s207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heppell J, Kelly KA, Phillips SF, Beart RW Jr, Telander RL, Perrault J. Physiologic aspects of continence after colectomy, mucosal proctectomy, and endorectal ileo-anal anastomosis. Ann Surg. 1982;195:435–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Nadalin W, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for stage 0 distal rectal cancer following chemoradiation therapy: long-term results. Ann Surg. 2004;240:711–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maas M, Beets-Tan RGH, Lambregts DMJ, et al. Wait-and-see policy for clinical complete responders after chemoradiation for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4633–4640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Habr-Gama A, Gama-Rodrigues J, São Julião GP, et al. Local recurrence after complete clinical response and watch and wait in rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation: impact of salvage therapy on local disease control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:822–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wrenn SM, Cepeda-Benito A, Ramos-Valadez DI, Cataldo PA. Patient perceptions and quality of life after colon and rectal surgery: what do patients really want? Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hupkens BJP, Martens MH, Stoot JH, et al. Quality of life in rectal cancer patients after chemoradiation: watch-and-wait policy versus standard resection - a matched-controlled study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:1032–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Low anterior resection syndrome score: development and validation of a symptom-based scoring system for bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2012;255:922–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sprangers MA, te Velde A, Aaronson NK; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Study Group on Quality of Life. The construction and testing of the EORTC colorectal cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire module (QLQ-CR38). Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:238–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, Kamm MA. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut. 1999;44:77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cercek A, Roxburgh CSD, Strombom P, et al. Adoption of total neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:e180071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith JJ, Chow OS, Gollub MJ, et al. ; Rectal Cancer Consortium. Organ Preservation in Rectal Adenocarcinoma: a phase II randomized controlled trial evaluating 3-year disease-free survival in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated with chemoradiation plus induction or consolidation chemotherapy, and total mesorectal excision or nonoperative management. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Temple LK, Bacik J, Savatta SG, et al. The development of a validated instrument to evaluate bowel function after sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1353–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen TY-T, Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. What are the best questionnaires to capture anorectal function after surgery in rectal cancer? Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2015;11:37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett AV, Keenoy K, Shouery M, Basch E, Temple LK. Evaluation of mode equivalence of the MSKCC Bowel Function Instrument, LASA Quality of Life, and Subjective Significance Questionnaire items administered by Web, interactive voice response system (IVRS), and paper. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:1123–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Habr-Gama A, Lynn PB, Jorge JMN, et al. Impact of organ-preserving strategies on anorectal function in patients with distal rectal cancer following neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:77–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juul T, Elfeki H, Christensen P, Laurberg S, Emmertsen KJ, Bager P. Normative data for the low anterior resection syndrome score (LARS score). Ann Surg. 2019;269:1124–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olopade FA, Norman A, Blake P, et al. A modified Inflammatory Bowel Disease questionnaire and the Vaizey Incontinence questionnaire are simple ways to identify patients with significant gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1663–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vailati BB, Habr-Gama A, Mattacheo AE, São Julião GP, Perez RO. Quality of life in patients with rectal cancer after chemoradiation: watch-and-wait policy versus standard resection-are we comparing apples to oranges? Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Battersby NJ, Bouliotis G, Emmertsen KJ, et al. ; UK and Danish LARS Study Groups. Development and external validation of a nomogram and online tool to predict bowel dysfunction following restorative rectal cancer resection: the POLARS score. Gut. 2018;67:688–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith JJ, Strombom P, Chow OS, et al. Assessment of a watch-and-wait strategy for rectal cancer in patients with a complete response after neoadjuvant therapy. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:e185896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.