Abstract

Background:

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is associated with increased risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). Whether clinically meaningful PTSD improvement is associated with lowering CVD risk is unknown.

Methods:

Eligible patients (n=1,079), were 30–70 years old, diagnosed with PTSD and used Veterans Health Affairs PTSD specialty clinics. Patients had a PTSD Checklist score (PCL) ≥ 50 between Fiscal Year (FY) 2008 and FY2012 and a second PCL score within 12 months and at least 8 weeks after the first PCL≥ 50. Clinically meaningful PTSD improvement was defined by ≥ 20 point PCL decrease between the first and second PCL score. Patients were free of CVD diagnoses for 1 year prior to index. Index date was 12 months following the first PCL. Follow-up continued to FY2015. Cox proportional hazard models estimated the association between clinically meaningful PTSD improvement and incident CVD and incident ischemic heart disease (IHD). Sensitivity analysis stratified by age group (30–49 vs. 50–70 years) and depression. Confounding was controlled using propensity scores and inverse probability of exposure weighting.

Results:

Patients were 48.9±10.9 years of age on average, 83.3% male, 60.1% white, and 29.5% black. Before and after controlling for confounding, patients with vs. without PTSD improvement did not differ in CVD risk (HR=1.08; 95%CI: 0.72–1.63). Results did not change after stratifying by age group or depression status. Results were similar for incident IHD.

Conclusions:

Over a 2–7 year follow-up, we did not find an association between clinically meaningful PTSD improvement and incident CVD. Additional research is needed using longer follow-up.

Keywords: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Psychotherapy, Cardiovascular Disease, Epidemiology, Veterans

INTRODUCTION

A large literature supports an association between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and incident cardiovascular disease (CVD), with risk ranging from 1.39 to 3.28.1–10 Some evidence indicates this association is partly or completely explained by comorbid conditions and health risk behaviors that may be mechanisms through which PTSD could lead to poor health.11 Specifically, in some,5,10 but not all studies2,3, the association between PTSD and incident CVD is attenuated or no longer present after adjusting for CVD risk factors such as smoking, depression, cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension, etc.

PTSD treatment and symptom reduction is associated with improvements in depression,12–14 sleep,15 reduction in miscellaneous health complaints such as back pain and coughing,15 and a lower risk for hypertension.16 A PTSD Checklist score decrease of 20 points or more compared to no improvement or less than a 20 point decrease is associated with reduced risk for incident type 2 diabetes (T2D) (HR=0.51; 95%CI:0.26–0.98).17

To our knowledge, only one existing study has evaluated the association between PTSD remission and CVD risk. Gilsanz and colleagues estimated the association between duration of PTSD and PTSD remission and CVD risk over a 20-year follow-up of the Nurses’ Health Study II. After robust control for confounding, results revealed that compared to respondents with no trauma, severe PTSD was associated with a 69% increased odds of CVD and remitted, mild PTSD symptoms had a lower, albeit not statistically significant (OR=0.70; 95%CI:0.39–1.25), risk for CVD.18

While a growing literature suggests PTSD treatment and symptom reduction is followed by improvement in some health conditions, evidence for a link between PTSD remission and lower risk for CVD is based on a single study of female civilians. Therefore, we sought to determine if clinically meaningful PTSD symptom reduction was associated with a decreased risk for incident CVD in male and female Veterans. Our primary objective was to estimate the risk of incident CVD in patients with vs. without a clinically meaningful PTSD improvement. Second, we determined if results differed by depression status and age group. Last, we computed risk for the more specific diagnosis of incident ischemic heart disease.

METHODS

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from participating institutions with a waiver of consent because data did not include identifiers. Existing administrative medical record data was obtained from patients who used one of five Veterans Health Affairs (VHA) PTSD specialty clinics distributed throughout the United States. PTSD specialty clinic encounters were between fiscal years (FY) 2008 to FY2012 and the observation period ended in FY2015.

Eligibility

A total of 5,916 patients, age 18–70, met our criteria for PTSD diagnosis. Between FY2008-FY2012, 3,618 patients had one or more PTSD Checklist (PCL) scores ≥ 50 which is consistent with having current PTSD (see Figure 1).19 There were 2,252 patients for whom we could measure change in PCL scores over a 12 month period by selecting the first PCL≥ 50 and a second PCL within 12 months and at least 8 weeks after the first PCL. The index date was 12 months following the first PCL and could occur between FY2009 and FY2013. Thus, all patients had a possible 2–7 years follow-up time after index for the outcome to occur. We excluded patients with prevalent CVD in the 12 months prior to index. Patients less than 30 have a very low risk for CVD, therefore, we limited the sample to patients 30–70 years of age. This resulted in an analytic sample of 1,079 FY patients with PTSD and without CVD at index date.

Figure 1.

Sample selection process

Variables

All variables were created from VHA medical record data which includes diagnostic codes, medications dispensed, laboratory results, vital signs, type of clinic encounters (e.g. primary care, psychiatry, PTSD specialty clinic, etc.), Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and demographic measures.

PTSD was defined as two outpatient visits within a 12-month period or one inpatient stay with ICD-9 code 309.81. Two diagnoses in a 4 month period has a positive predictive value of 82% when compared to a gold standard PTSD Checklist (PCL) score ≥50,20 and two PTSD diagnoses has an 88.4% agreement with lifetime diagnosis obtained via the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.21

Exposure:

A PCL decrease of 20 points or greater is consistent with a large, clinically meaningful PTSD improvement.22 Based on the difference between the first PCL ≥ 50 and the last PCL within 12 months and at least 8 weeks after the first PCL, patients were assigned to those with a clinically meaningful improvement (i.e. ≥20 point PCL decrease) vs. those with <20 point PCL decrease or no PTSD symptom decrease.

Outcome:

Incident CVD was defined by an inpatient or outpatient ICD-9 codes for hypertensive heart disease, myocardial infarction (MI), ischemic heart disease or ‘other’ heart disease. A detailed list of ICD-9 codes used to measure CVD conditions is shown in Appendix-1. Sensitivity analysis limited the outcome to MI/ischemic heart disease. CPT codes for revascularization procedures counted toward a CVD diagnosis, however, all patients with a revascularization procedure also had a diagnostic code.

Covariates:

Age, race, gender, marital status and access to non-VHA health insurance were measured at the start of the observation period. All other covariates were measured up to the index date and included diagnoses for depression, other anxiety disorders, sleep disorder, substance use disorders, smoking status, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, minimally adequate duration of PTSD psychotherapy (i.e. ≥9 visits in any 15 week period) and receipt of acute phase antidepressant medication (i.e. 12 weeks). Detailed variable definitions are shown in Appendix-1.

Control for confounding:

We controlled for confounding by balancing the distribution of covariates between patients with and without a clinically meaningful PCL decrease using propensity scores (PS) and inverse probability of exposure weighting (IPEW). We chose this approach over PS matching because subjects are often lost when matching on the PS. When PS and IPEW balance covariates, analysis reduces bias in the estimation of the total average treatment effect of clinically meaningful PTSD improvement on incident CVD. The PS is computed from a logistic regression model that estimates the probability of patients experiencing vs. not experiencing clinically meaningful PTSD improvement given covariates.23 The PS is used to compute a stabilized weight,24,25 calculated as the marginal probability of experiencing clinically meaningful PCL decrease divided by the PS for having a clinically meaningful PCL decrease for those with decrease ≥20 and (1-marginal probability ≥20 decrease)/(1-PS of ≥ 20 decrease) for those with < 20 point decrease. A pseudo-population is created after applying IPEW and confounding is controlled when variables balance between patients with and without a clinically meaningful PCL decrease. Well-behaved weights have a maximum value <10 and a mean close to one.25–27 IPEW generates a pseudo-population in which confounding is controlled if standardized mean differences (SMD%) are all <10%.25–27 SMD<10% is consistent with balanced variables between groups with and without a clinically meaningful PCL decrease.

Analytic approach:

To measure the association between potential confounding variables and clinically meaningful PTSD improvement, we computed descriptive analysis and chi-square tests for categorical variables and independent samples t-tests for continuous variables. Prior to weighting data, we computed Poisson regression models to calculate CVD incidence rates per 1,000 person-years (PY). In unweighted data, we computed bivariate Cox proportional hazard models to estimate the association between each potential confounder with incident CVD.

In unweighted and weighted data, we computed Cox proportional hazard models to estimate the association between clinically meaningful PCL decrease and incident CVD. The unit of follow-up time was in days and measured from index date to either incident CVD or last available VHA encounter.

Results were expressed by hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Robust, sandwich-type variance estimators were used to calculate confidence intervals and p-values in weighted data. For all models, the proportional hazard assumption was tested and met. SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses and an alpha level of 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Sensitivity analyses:

Because the primary CVD outcome was a broad definition, separate Cox proportional hazard models were computed for incident ischemic heart disease, defined by myocardial infarction or ischemic heart disease. Depression occurs in about 50% of patients with PTSD28 and is associated with incident CVD.29 Therefore, we stratified analysis by depression diagnoses to assess whether effects differed in those with versus without depression. Last, based on evidence that PTSD may be associated with early onset CVD,6 we computed separate survival models in patients 30–49 years of age vs. ≥50 years of age.

RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, the sample as a whole was 48.9±10.9 years of age on average, 83.3% male, 60.1% white, 29.5% black and 49.9% were married. Nearly 23% (n=247) experienced a clinically meaningful PTSD improvement. Having only VHA health insurance was significantly more common in patients with vs. without a clinically meaningful PTSD improvement (62.8% vs. 55.5%; χ2(1)=4.1, p=0.044). The average first PCL was significantly greater in patients with vs. without meaningful PTSD improvement (66.4±8.5 vs. 64.8±9.2; t(1077)=2.5, p=0.013), though the absolute magnitude of mean differences was small. The mean of the second PCL was substantially and significantly less in those with vs. without meaningful PTSD improvement (35.7±9.9 vs. 62.2±11.9; t(1077)=−31.9, p<.0001). Receipt of minimally adequate duration of PTSD psychotherapy was significantly more prevalent among those with vs. without a clinically meaningful PTSD improvement (60.3% vs. 46.6%; χ2(1)=14.3, p=0.0002). Comorbid conditions, smoking and antidepressant treatment did not significantly differ by PTSD improvement.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics overall and by PCL decrease for Veterans Health Affairs (VHA) PTSD cases, veterans age 30–70 years and free of CVD (n=1,079)

| Variable, n(%) or mean (±sd) | Overall (n=1,079) | PCL dec < 20 (n=832) | PCL dec ≥ 20 (n=247) | t or χ2 (df) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (±sd) | 48.9 (±10.9) | 48.6 (±11.0) | 49.8 (±10.8) | 1.5 (1077) | .13 |

| Male gender, n(%) | 899 (83.3) | 700 (84.1) | 199 (80.6) | 1.7 (1) | .19 |

| Race, n(%) | |||||

| White | 648 (60.1) | 492 (59.1) | 156 (63.2) | ||

| Black | 318 (29.5) | 248 (29.8) | 70 (28.3) | 1.9 (3) | .60 |

| Other | 79 (7.3) | 64 (7.7) | 15 (6.1) | ||

| Missing | 34 (3.2) | 28 (3.4) | 6 (2.4) | ||

| Married, n(%) | 539 (49.9) | 415 (49.9) | 124 (50.2) | 0.08 (1) | .93 |

| VHA only insurance, n(%) | 617 (57.2) | 462 (55.5) | 155 (62.8) | 4.1 (1) | .044 |

| High primary HCU, n(%) | 271 (25.1) | 215 (25.8) | 56 (22.7) | 1.0 (1) | .31 |

| First PCL severe (≥70), n(%) | 365 (33.8) | 273 (32.8) | 92 (37.3) | 1.7 (1) | .20 |

| First PCL, mean (±sd) | 65.1 (±9.0) | 64.8 (±9.2) | 66.4 (±8.5) | 2.5 (1077) | .013 |

| Last PCL, mean (±sd) | 56.1 (±16.0) | 62.2 (±11.9) | 35.7 (±9.9) | −31.9 (1077) | <.0001 |

| Psychiatric comorbidities and treatmentsa | |||||

| Depression, n(%) | 813 (75.3) | 628 (75.5) | 185 (74.9) | 0.03 (1) | .85 |

| Other anxietyb, n(%) | 289 (26.8) | 221 (26.6) | 68 (27.5) | 0.09 (1) | .76 |

| Sleep disorder, n(%) | 546 (50.6) | 420 (50.5) | 126 (51.0) | 0.02 (1) | .88 |

| Substance abuse/dependence, n(%) | 452 (41.9) | 343 (41.2) | 109 (44.1) | 0.7 (1) | .42 |

| Smokingc, n(%) | |||||

| Never | 448 (41.5) | 348 (41.8) | 100 (40.5) | ||

| Former | 135 (12.5) | 105 (12.6) | 30 (12.2) | 0.3 (1) | .88 |

| Current | 496 (46.0) | 379 (45.6) | 117 (47.4) | ||

| Adequate PTSD psychotherapy, n(%)d | 537 (49.8) | 388 (46.6) | 149 (60.3) | 14.3 (1) | .0002 |

| Adequate ADM treatment, n(%)e | 815 (75.5) | 640 (76.9) | 175 (70.8) | 3.8 (1) | .05 |

| Physical comorbiditiesa | |||||

| Type 2 diabetes, n(%) | 127 (11.8) | 94 (11.3) | 33 (13.4) | 0.8 (1) | .38 |

| Hypertension, n(%) | 507 (47.0) | 392 (47.1) | 115 (46.6) | 0.02 (1) | .88 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n(%) | 497 (46.1) | 385 (46.3) | 112 (45.3) | 0.07 (1) | .80 |

| Obesityf, n(%) | 616 (57.1) | 466 (56.0) | 150 (60.7) | 1.7 (1) | .19 |

PTSD=posttraumatic stress disorder; PCL=PTSD checklist (range: 17–85); FY=fiscal year; DEC=decrease; HCU=healthcare utilization; ADM=antidepressant

Comorbidities occur from start of FY2008 to index date

Composite of panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, anxiety not otherwise specified.

Health factors or ICD-9-CM code

Measured in exposure year. Presence of at least 9 psychotherapy visits in any 15 week period.

At least 12 weeks of continuous ADM fills prior to index date

BMI≥30 or ICD-9-CM code

Bivariate associations between covariates and incident CVD are shown in Table 2. Each additional year of age was associated with a 6% increased risk for CVD (χ2(1)=50.2, p<0.0001), and males were 105% more likely to develop CVD (χ2(1)=6.1, p=0.014). Compared to never smokers, former smokers (χ2(1)=4.6, p=0.032) and current smokers (χ2(1)=5.0, p=0.026) were 73% and 52% significantly more likely, respectively, to develop CVD. Patients who received minimally adequate duration of PTSD psychotherapy were 56% more likely to have incident CVD (χ2(1)=6.8, p=0.009). Type 2 diabetes (HR=2.12; χ2(1)==13.4, p=0.0003), hypertension (HR=2.18; χ2(1)=20.1, p<0.0001) and hyperlipidemia (HR=2.05; χ2(1)==17.6, p<0.0001) were all associated with greater risk for incident CVD.

Table 2.

Crude hazard ratios – bivariate relationship of each individual covariate with CVD, veterans age 30–70 years and free of CVD (n=1,079) in the Veterans Health Affairs (VHA)

| Covariate | Crude HR (95% CI) | χ2 (df) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| First PCL severe (≥70) | 1.02 (0.72–1.43) | 0.01 (1) | .92 |

| Age | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | 50.2 (1) | <.0001 |

| Male gender | 2.05 (1.16–3.62) | 6.1 (1) | .014 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1.00 | ||

| Black | 0.73 (0.50–1.07) | 2.6 (1) | .11 |

| Other | 0.67 (0.34–1.32) | 1.3 (1) | .25 |

| Married | 1.04 (0.75–1.44) | 0.05 (1) | .82 |

| VHA only insurance | 0.80 (0.58–1.11) | 1.8 (1) | .17 |

| High primary HCU | 1.29 (0.91–1.84) | 2.0 (1) | .15 |

| Depression | 1.53 (1.00–2.36) | 3.8 (1) | .05 |

| Other anxiety | 1.20 (0.84–1.71) | 1.0 (1) | .32 |

| Sleep disorder | 1.10 (0.79–1.52) | 0.3 (1) | .59 |

| Substance abuse/dependence | 1.29 (0.92–1.78) | 2.2 (1) | .14 |

| Smoking | |||

| Never | 1.00 | ||

| Former | 1.73 (1.05–2.85) | 4.6 (1) | .032 |

| Current | 1.52 (1.05–2.18) | 5.0 (1) | .026 |

| Adequate PTSD psychotherapy | 1.56 (1.12–2.18) | 6.8 (1) | .009 |

| Adequate ADM treatment | 0.80 (0.56–1.15) | 1.4 (1) | .23 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 2.12 (1.42–3.17) | 13.4 (1) | .0003 |

| Hypertension | 2.18 (1.55–3.06) | 20.1 (1) | <.0001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 2.05 (1.46–2.87) | 17.6 (1) | <.0001 |

| Obesity | 1.25 (0.90–1.75) | 1.7 (1) | .19 |

HCU=healthcare utilization; PCL=PTSD checklist; PTSD=posttraumatic stress disorder; ADM=antidepressant

In the total cohort, 145 patients developed CVD during follow-up. Types of diagnosed incident CVD were not necessarily mutually exclusive. Of those with CVD, 55.2% had ‘other’ heart disease and 45.5% had ischemic heart disease. Less than 6 patients had hypertensive heart disease diagnoses. To protect confidentiality, we do not report the exact number of patients and percentage when there are 5 or fewer cases..

The age-adjusted cumulative CVD incidence was similar in patients with and without a clinically meaningful PTSD improvement (11.5% vs. 11.4%, χ2(1)=0.005, p=0.94). Similarly the age-adjusted incidence rate per 1000 Person Years (PY) was not significantly different between groups (χ2(1)=0.2, p=0.67). Among those with a clinically meaningful PTSD improvement, the age-adjusted CVD incidence rate was 35.0/1000PY compared to 32.2/1000PY in patients without a clinically meaningful improvement.

IPEW resulted in stabilized weights that ranged from 0.36 to 3.67 with a mean =1.00 (SD±0.26). There were no extreme weights > 10 and thus no weights were trimmed. As shown in Table 3, IPEW successfully balanced potential confounding variables between patients with and without a clinically meaningful PTSD improvement. This is evidenced by all SMDs<10% in the weighted data.

Table 3.

SMD unweighted and weighted for potential confounders

| Variable | Unweighted | Weighted |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 11.1% | 1.9% |

| Male gender | −9.4% | 2.1% |

| Race | ||

| White | 8.3% | 1.6% |

| Black | −3.2% | −3.1% |

| Other | −6.4% | 4.9% |

| Missing | −5.6% | −4.3% |

| Married | 0.7% | −4.4% |

| VHA only insurance | 14.7% | −2.8% |

| High primary HCU | −7.4% | 1.1% |

| First PCL severe (≥70) | 9.3% | −2.6% |

| Psychiatric comorbidities and treatments | ||

| Depression | −1.4% | 1.2% |

| Other anxiety | 2.2% | −4.4% |

| Sleep disorder | 1.1% | −3.7% |

| Substance abuse/dependence | 5.9% | 2.4% |

| Smoking | ||

| Never | −2.7% | −5.2% |

| Former | −1.4% | 1.6% |

| Current | 3.6% | 4.1% |

| Adequate PTSD psychotherapy | 27.7% | −2.3% |

| Adequate ADM treatment | −13.9% | 1.2% |

| Physical comorbidities | ||

| Type 2 diabetes | 6.3% | 2.3% |

| Hypertension | −1.1% | 2.0% |

| Hyperlipidemia | −1.9% | 1.1% |

| Obesity | 9.6% | 6.2% |

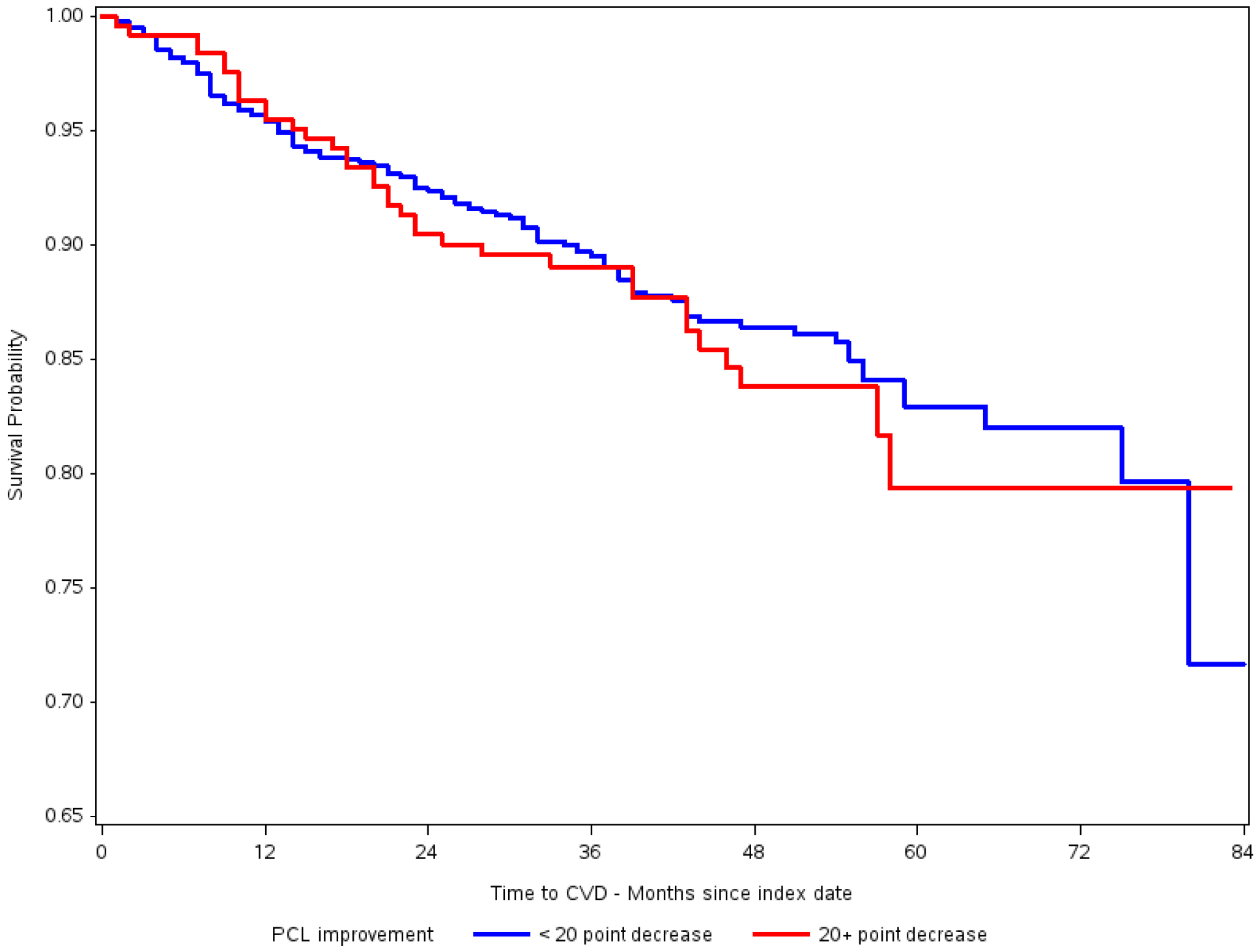

Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve for the relationship of clinically meaningful PTSD improvement and incident CVD. As shown in Table 4, both before and after controlling for confounding using weighted data, we found no association between clinically meaningful PTSD improvement and incident CVD. In weighted data (Model 3), patients with vs. without clinically meaningful PTSD improvement did not significantly differ in risk for CVD (HR=1.08; 95%CI:0.72–1.63). The lack of association remained in patients 30–49 years of age (HR=1.02; 95%CI:0.46–2.26) and those 50 to 70 years of age (HR=1.13; 95%CI:0.71–1.80). Results did not change after stratifying analysis by depression status, and when modeling the association between clinically meaningful PTSD improvement and IHD.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve for the relationship of PTSD symptom decrease and incident CVD

Table 4.

Results from Cox proportional hazards models estimating the association of PCL decrease and incident CVD among veterans with PTSD a age 30–70 years (n=1,079)

| Model 1 – Crude HR (95% CI) |

Model 2– Age-Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

Model 3 – Weighted HR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | |||

| PCL decrease ≥ 20 | 1.12 (0.77–1.65) | 1.08 (0.74–1.59) | 1.08 (0.72–1.63) |

| χ2 (df) | 0.4 (1) | 0.2 (1) | 0.2 (1) |

| p-value | .55 | .68 | .69 |

| Age groups | |||

| Age 30–49 | |||

| PCL decrease≥ 20 | - | - | 1.02 (0.46–2.26) |

| χ2 (df) | 0.003 (1) | ||

| p-value | .96 | ||

| Age 50–70 | |||

| PCL decrease ≥ 20 | - | - | 1.13 (0.71–1.80) |

| χ2 (df) | 0.3 (1) | ||

| p-value | .61 | ||

| Stratified on depression | |||

| No depression | |||

| PCL decrease ≥ 20 | - | - | 0.94 (0.34–2.59) |

| χ2 (df) | 0.02 (1) | ||

| p-value | .90 | ||

| Depression | |||

| PCL decrease ≥ 20 | - | - | 1.13 (0.72–1.75) |

| χ2 (df) | 0.3 (1) | ||

| p-value | .60 | ||

| MI/Ischemic heart disease | |||

| PCL decrease≥ 20 | 1.22 (0.71–2.10) | ||

| χ2 (df) | 0.5 (1) | ||

| p-value | .46 | ||

DISCUSSION

In a large sample of VHA patients with PTSD, we did not find evidence that improvement in PTSD symptoms was associated with lower risk for incident CVD or incident IHD. This result was consistent in patients with and without comorbid depression and in patients 30–49 years of age compared to those 50 to 70 years of age.

The lack of an association between PTSD improvement and incident CVD is, to some extent, not consistent with a 20 year follow-up of women in the Nurses’ Health Study II.18 In this prior study, compared to patients without trauma, those with persistent, severe PTSD symptoms had 2.28 times greater odds of CVD defined as incident MI and stroke. Although point estimates were not statistically significant, women with remitted mild PTSD were 30% less likely to develop CVD (OR=0.70; 95%CI:0.39–1.25), and remitted moderate to severe PTSD was not associated with incident CVD (OR=1.07; 95%CI:0.55–2.08).18 It is difficult to directly compare our results to this prior study, which used a non-trauma reference group and defined CVD as an MI or stroke; however, the present results in a sample of VHA patients with moderate to severe PTSD are consistent with evidence from the Nurses’ Health Study II that revealed there was no association between remitted moderate to severe PTSD and incident CVD.

In prior analysis using a similar design, we observed that clinically meaningful PTSD symptom decrease compared to less than a clinically meaningful decrease was associated with a 49% lower risk for T2D.17 As compared to VHA patients without PTSD, we previously observed a 29% increased risk for hypertension in patients who did not experience a clinically meaningful PTSD improvement. In the same study, compared to no PTSD, clinically meaningful PTSD improvement was not associated with incident hypertension.

Reductions in chronic stress likely occur in patients who experience decreases in PTSD symptoms. Reductions in chronic stress may have an immediate impact on T2D and hypertension risk given research showing some forms of stress reduction techniques are associated with large decreases in blood pressure,30 and stress management can lead to improved glycemic control.31 Glucose and blood pressure could be more sensitive to changes in chronic stress as compared to other mechanisms leading to CVD. Atherosclerotic plaque may not be reversed in a short time frame after large PTSD improvement. A landmark autopsy study of Vietnam Veteran causalities revealed the etiology of CVD begins in young adults, with 45% of causalities having some coronary atherosclerosis.32 We speculate that atherosclerosis may be present prior to Veterans seeking PTSD treatment, and it is possible that even substantial PTSD improvements may not completely reverse established atherosclerosis.

Our results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Misclassification from the use of diagnostic codes to identify CVD could bias hazard ratios if CVD was over- or under-diagnosed. Residual confounding may influence our results. We did not have data on trauma type and we did not have measures of specific PTSD symptoms which may have varying magnitudes of association with CVD. Last, our follow-up time was relatively short. CVD develops over many years and future research is needed to determine if sustained PTSD improvement might be associated with a reduced risk for CVD over 10 to 20 years of follow-up. This may be possible if PTSD improvement slows or prevents worsening atherosclerosis.

Conclusions

We did not find that clinically meaningful PTSD symptom decrease was associated with incident CVD over a 2–7 year follow-up in VHA patients 30–70 years of age. Future research is warranted to determine if clinically meaningful PTSD improvement is associated with slower progression of CVD. Studies of patients with comorbid PTSD and CVD are needed to determine if large, clinically meaningful PTSD improvement is associated with a decreased risk for adverse CVD outcomes.

Highlights.

PTSD improvement has been linked to improvement in some health conditions

Determined if large PTSD improvement associated with incident cardiovascular disease (CVD)

Patients assigned to those with vs. without a ≥ 20 point PTSD Checklist (PCL) score decrease

No association between ≥ 20 point PTSD Checklist (PCL) score decrease and incident CVD

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of the Veterans Administration.

Funding: National Institute of Mental Health, PTSD Treatment: Effects on Health Behavior, Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disease, R01HL125424.

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans’ Hospital

Appendix 1.

Variable definitions table

Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) - ≥1 ICD9 diagnosis code or revascularization CPT/ICD9 procedure codes

|

|

PCL checklist score difference (range of scores for PCL is 17–85) First PCL and last PCL in exposure year must be at least 8 weeks apart. A significant PCL decrease is defined as ≥ 20 point decrease (yes or no) |

|

First PCL severity Severe - 70–85 Moderate - 50–69 |

| End of follow-up = CVD date or last visit date if no CVD |

| Baseline sociodemographics: Age, Gender, Race, marital status, VA only insurance |

| Primary healthcare utilization - number of unique primary care clinic stops per total months in entire VA system. Total months is calculated from first visit date to any VA facility in FY08 to FY15 to the index date. Stop codes from first VA visit to index date: 170, 172, 301, 322, 323, 348, 350 |

| Depression –Presence of a single inpatient code or ≥2 outpatient codes within a 12 month period. Measured prior to index date. (296.2x, 296.3x, 311) |

| Other anxiety – Presence of a single inpatient code or ≥2 outpatient codes within a 12 month period. Measured prior to index date. Composite of panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, anxiety nos (300.00, 300.01, 300.02, 300.23, 300.3) |

| Sleep disorder - At least a single code for 307.4x, 327.x, 780.5x, 333.94 before index date |

| Substance abuse/dependence –Presence in record of at least a single code for any alcohol or drug/abuse dependence before index date. Composite of alcohol (303.9x, 305.0x), sedative (304.1x, 305.4x), cocaine (304.2x, 305.6x), cannabis (304.3x, 305.2x), amphetamine (304.4x, 305.7x), hallucinogens (304.5x, 305.3x), ‘other’ (304.6x, 305.9x), opioid (304.0x, 305.5x), opioid with other SUD (304.7x), other SUD excluding opioid (304.8x), unspecified drug abuse/dependence (304.9x). |

Smoking/nicotine dependence – Never vs. Former vs. Current at index

|

| Adequate ADM treatment – any continuous period of ≥12 weeks ADM fills prior to index date. ADMs are: selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs: citalopram, escitalopram, fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and vilazodone); serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs: venlafaxine, duloxetine, milnacipran, and desvenlafaxine); tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs: amitriptyline, desipramine, doxepine, imipramine, nortriptyline, trimipramine, clomipramine, maprotiline, protriptyline, amoxapine); non-classified antidepressants (bupropion, nefazodone, trazodone, and mirtazapine); and monamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs: selegiline, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, and isocarboxazid). |

| PTSD Psychotherapy = from the first PCL date to index date. Clinic stop codes include 516, 540, 541, 561, 562 at ‘gold standard clinics’ (STA6A=534, 539, 662, 664, 664BY). Classified as adequate treatment (in any 15 week period, had 9+ visits) - yes vs. no |

| Type 2 Diabetes – Presence of ≥2 ICD9 codes in any 24-month period before index date (250.x0, 250.x2, 357.2, 362.0x, 366.41) |

| Hypertension – At least one code present before index date (401.x) |

| Hyperlipidemia - At least one code present before index date (272.0, 272.1, 272.2, 272.4) |

| Obese – Either a BMI ≥30 or ICD9 (278.00, 278.01) code for obesity before index date. |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: none

Conflict of interest: none

REFERENCES

- 1.Edmondson D, Cohen BE. Posttraumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2013;55(6):548–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kubzansky LD, Koenen KC, Spiro A 3rd, Vokonas PS, Sparrow D. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and coronary heart disease in the Normative Aging Study. Archives of general psychiatry. 2007;64(1):109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubzansky LD, Koenen KC, Jones C, Eaton WW. A Prospective Study of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms and Coronary Heart Disease in Women. Health Psychol. 2009;28(1):125–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koenen KC, Sumner JA, Gilsanz P, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiometabolic disease: improving causal inference to inform practice. Psychol Med. 2017;47(2):209–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sumner JA, Kubzansky LD, Elkind MSV, et al. Trauma Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms Predict Onset of Cardiovascular Events in Women. Circulation. 2015;132(4):251–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boscarino JA. A prospective study of PTSD and early-age heart disease mortality among Vietnam veterans: implications for surveillance and prevention. Psychosomatic medicine. 2008;70(6):668–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boscarino JA. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease link: time to identify specific pathways and interventions. The American Journal Of Cardiology. 2011;108(7):1052–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, Grant BF. Medical comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in US adults: results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychosomatic medicine. 2011;73(8):697–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaccarino V, Goldberg J, Rooks C, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and incidence of coronary heart disease: a twin study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(11):970–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scherrer JF, Salas J, Cohen BE, et al. Comorbid Conditions Explain the Association Between Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Incident Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(4):e011133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnurr PP, Green BL. Understanding relationships among trauma, PTSD, and health outcomes In: Green PPSBL, ed. Trauma and health: Physical health consequences of exposure to extreme stress Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004:247–275. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rauch SA, Grunfeld TE, Yadin E, Cahill SP, Hembree E, Foa EB. Changes in reported physical health symptoms and social function with prolonged exposure therapy for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and anxiety. 2009;26(8):732–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Resick PA, Williams LF, Suvak MK, Monson CM, Gradus JL. Long-term outcomes of cognitive-behavioral treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder among female rape survivors. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2012;80(2):201–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resick PA, Wachen JS, Dondanville KA, et al. Effect of Group vs Individual Cognitive Processing Therapy in Active-Duty Military Seeking Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA psychiatry. 2017;74(1):28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galovski TE, Monson C, Bruce SE, Resick PA. Does cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD improve perceived health and sleep impairment? Journal of traumatic stress. 2009;22(3):197–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burg MM, Brandt C, Buta E, et al. Risk for Incident Hypertension Associated With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Military Veterans and the Effect of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Treatment. Psychosomatic medicine. 2017;79(2):181–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scherrer JF, Salas J, Norman SB, et al. Association Between Clinically Meaningful Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Improvement and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA psychiatry. 2019. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilsanz P, Winning A, Koenen KC, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptom duration and remission in relation to cardiovascular disease risk among a large cohort of women. Psychol Med. 2017;47(8):1370–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behaviour research and therapy. 1996;34(8):669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gravely AA, Cutting A, Nugent S, Grill J, Carlson K, Spoont M. Validity of PTSD diagnoses in VA administrative data: comparison of VA administrative PTSD diagnoses to self-reported PTSD Checklist scores. Journal of rehabilitation research and development. 2011;48(1):21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holowka DW, Marx BP, Gates MA, et al. PTSD diagnostic validity in Veterans Affairs electronic records of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2014;82(4):569–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monson CM, Gradus JL, Young-Xu Y, Schnurr PP, Price JL, Schumm JA. Change in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: do clinicians and patients agree? Psychological assessment. 2008;20(2):131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika Trust. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis LH, Hammill BG, Eisenstein EL, Kramer JM, Anstrom KJ. Using inverse probability-weighted estimators in comparative effectiveness analysis with observational databases. . Med Care. 2007;45:S103–S107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Statistics in medicine. 2015;34(28):3661–3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole SR, Hernan MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. American journal of epidemiology. 2008;168(6):656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sturmer T, Wyss R, Glynn RJ, Brookhart MA. Propensity scores for confounder adjustment when assessing the effects of medical interventions using nonexperimental study designs. Journal of internal medicine. 2014;275(6):570–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brady KT, Killeen TK, Brewerton T, Lucerini S. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2000;61 Suppl 7:22–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whooley MA, Wong JM. Depression and cardiovascular disorders. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2013;9:327–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spruill TM. Chronic psychosocial stress and hypertension. Current Hypertension Reports. 2010;12:10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lloyd C, Smith J, Weinger K. Stress and diabetes: a review of the links. Diabetes Spectrum. 2005;18:121–127. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McNamara JJ, Molot MA, Stremple JF, Cutting RT. Coronary artery disease in combat casualties in Vietnam. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1971;216(7):1185–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]