Abstract

Objective

To determine whether women with multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosed according to current criteria are at an increased risk of postpartum relapses and to assess whether this risk is modified by breastfeeding or MS disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), we examined the electronic health records (EHRs) of 466 pregnancies among 375 women with MS and their infants.

Methods

We used prospectively collected information from the EHR at Kaiser Permanente Southern and Northern California between 2008 and 2016 of the mother and infant to identify treatment history, breastfeeding, and relapses. Multivariable models accounting for measures of disease severity were used.

Results

In the postpartum year, 26.4% relapsed, 87% breastfed, 36% breastfed exclusively for at least 2 months, and 58.8% did not use DMTs. At pregnancy onset, 67.2% had suboptimally controlled disease. Annualized relapse rates (ARRs) declined from 0.37 before pregnancy to 0.14–0.07 (p < 0.0001) during pregnancy, but in the postpartum period, we did not observe any rebound disease activity. The ARR was 0.27 in the first 3 months postpartum, returning to prepregnancy rates at 4–6 months (0.37). Exclusive breastfeeding reduced the risk of early postpartum relapses (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.37, p = 0.009), measures of disease severity increased the risk, and resuming modestly effective DMTs had no effect (time-dependent covariate, p = 0.62).

Conclusion

Most women diagnosed with MS today can have children without incurring an increased risk of relapses. Women with suboptimal disease control before pregnancy may benefit from highly effective DMTs that are compatible with pregnancy and lactation. Women with MS should be encouraged to breastfeed exclusively.

Women with multiple sclerosis (MS) are widely counseled that their risk of relapse will decline during pregnancy only to rebound in the early postpartum period before returning to their prepregnancy risk later in the postpartum year. These counseling recommendations are based on the findings from a study of women recruited from multiple referral centers over 24 years ago.1 Since then, MS diagnostic criteria have been revised to allow for earlier diagnosis and diagnosis of milder cases, calling into question the generalizability of these findings in contemporary MS populations.

The fear of postpartum relapses affects family planning, treatment, and breastfeeding choices. Women must choose whether to forego breastfeeding, forego MS disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), or accept the uncertain risks of breastfeeding while on a DMT. Although the infant and maternal health benefits of prolonged breastfeeding are well established, whether resuming DMTs reduces the risk of postpartum MS relapses has yet to be demonstrated.2–4

Previous studies that have attempted to address these controversies have significant methodological limitations including selection bias,2,4–8 referral center bias,2,4–8 small sample,6,7 and incomplete or poor measures1,5,7,8 of breastfeeding and yielded mixed results. For example, breastfeeding exclusively for at least 2 months has been associated with a reduced risk of postpartum relapses,4,6 some breastfeeding with no effect1,5,8 or marginal benefit,9 and more formula feedings among breastfeeding women with an increased risk of postpartum relapses.10 A meta-analysis of breastfeeding and postpartum MS relapse risk showed a potentially protective effect but raised questions about incompletely controlling for confounding by indication,11 particularly since resuming DMTs while breastfeeding were mutually exclusive events because women with more active disease before pregnancy were being counseled to forego breastfeeding to resume medications.7 Resuming DMTs within 2 weeks,3 24 or 3 months,2 or sometime during the postpartum year8 has failed to demonstrate benefit.

The objective of this study was to assess the risk of pregnancy-associated MS relapses in a contemporary, population-based cohort and to identify whether breastfeeding or treatment choices modify these risks.

Methods

Study population

Pregnant women with MS or its precursor, clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), were identified through the membership of Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) and Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC). We searched electronic databases to identify members with MS or CIS with live births between January 2008 and April 2016 using a combination of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision or Tenth Revision codes for MS or CIS and pregnancy.3 The complete electronic health records (cEHRs) were reviewed to determine eligibility by an MS expert (A.L.-G.). All KPSC and KPNC members who met the 2010 McDonald criteria for MS,12 regardless of subtype, or CIS13 during or at the onset of pregnancy were included.

KPSC and KPNC provide care to over 7 million members in California. Approximately 20% and 30% of the general population in the geographic areas served belong to the health plans in Southern and Northern California, respectively. The sociodemographic characteristics of KPSC and KPNC members are generally representative of the underlying population.14

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The study protocol was approved by the KPSC and KPNC institutional review board.

Data collection

Symptom onset, relapses, and disability level were abstracted from the mother's cEHR by an MS expert (A.L.-G.) blinded to treatment history and breastfeeding. Relapses were defined as the occurrence, reappearance, or worsening of symptoms of neurologic dysfunction lasting for 48 hours or more and needed to be documented by a treating physician during a physical examination. Symptoms that occurred within 1 month of each other were part of the same relapse. No MS-related disability was defined as documentation of a normal/near-normal neurologic examination, no fatiguing limb weakness, or significant visual or bladder impairment. Treatment history was collected through electronic searches and verified via cEHR review conducted by a research professional.

Breastfeeding, formula feeding, and introduction of solid food were abstracted from the infant's medical record by a research professional blinded to the mother's clinical history. This information is routinely recorded via a standard questionnaire administered by nursing staff at the infant well-baby/immunization visits at 2 days, 2 weeks, and 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12 months of age. After the 2-month visit, if an infant was noted to be breastfeeding one visit but had stopped by the subsequent visit, the mother's cEHR was reviewed for mention of breastfeeding, and the last recorded date of breastfeeding was chosen as the stop date.

Statistical analyses

To describe the natural history of MS, we calculated annualized relapse rates (ARRs) for the 2 years before pregnancy, each trimester during pregnancy, and each 3-month interval during the postpartum year. The relapse rate was calculated in each period by using the annualized relapses (calculated by dividing the actual relapses in the period by time in years, 0.33 for most) divided by the total pregnancies in that period (or women at risk for the 2 years before pregnancy). The 95% confidence interval (CI) and values comparing pregnancy and postpartum trimesters to the prepregnancy period were calculated by Poisson regression. Generalized estimation equations were used to account for women with multiple pregnancies.

Breastfeeding was defined a priori as exclusive (no formula feedings for at least the first 2 months postpartum) as in previous studies,4,6 nonexclusive (breast and formula feedings within 2 months), or none (reference group). The 2-month mark was chosen in this and previous studies4,6 because it is when milk supply becomes well established (i.e., the hardest months to get through) and attainable. In accordance with intention to treat, women who stopped breastfeeding within 2 months postpartum after an MS relapse (n = 2) were classified as breastfeeding exclusively.

The association between breastfeeding and use of DMT in the postpartum period and the time to onset of the first postpartum relapse was determined by survival analysis. Adjusted and unadjusted hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated by using the Cox proportional hazards regression. Primary analyses assessed the associations with the time to onset within the first 6 months postpartum because this is when postpartum rebound disease activity has been reported and when exclusive breastfeeding ends naturally with introduction of solids.4 Exclusive breastfeeding was modeled as a fixed covariate, and DMT use was modeled as a time-dependent covariate in the data analysis. To allow for comparison, estimates of breastfeeding and postpartum DMT use were adjusted, both singly and in combination, for age and disease duration at the onset of pregnancy (in years), relapse frequency in the 2 years before conception (0–1 or ≥2), treatment with DMTs in the year before pregnancy (yes/no), MS-related disability (yes/no), and relapses during pregnancy (yes/no). The independent effects of these factors were also tested. The robust sandwich covariance matrix estimate was used in all models to account for women with multiple pregnancies. All models were hypothesis driven and defined based on a priori knowledge of potential measures of disease severity (age, relapse frequency, relapses during pregnancy, disability, and disease duration). Prepregnancy DMT use was included because it has been associated with decision to breastfeed or resume DMTs in previous studies.4

Because interferon-beta (IFN-beta) and glatiramer acetate (GLAT), the most commonly used postpartum DMTs, have a delayed onset of action as previously suggested,2 we conducted secondary analyses examining DMT use over the entire postpartum year and whether early postpartum DMT use (within 2 months postpartum and before a relapse) reduced the risk of subsequent postpartum relapses.

To determine whether the effect of breastfeeding or DMT use varies by disease severity, we conducted sensitivity analyses in women with suboptimally controlled disease at pregnancy onset defined as 1 or more relapses in the 2 years before pregnancy and/or neurologic disability. To explore whether the continued lack of rebound disease activity we observed was due to exclusive breastfeeding, we restricted ARR calculations to only those women who did not breastfeed exclusively and had suboptimally controlled disease at pregnancy onset.

Propensity score (PS)-adjusted Cox regression models were also examined. Predicted probability of exclusive breastfeeding or resuming DMTs within 2 months postpartum was modeled using the logistic regression model. This included the same covariates as in the standard multivariable models for DMT use. Because the decision to breastfeed precedes postpartum DMT use, this variable was not included in the propensity to breastfeed exclusively. The Cox regression models were then adjusted for the PS quintiles derived from the logistic regression model.

The 5 cases in which MS onset occurred during pregnancy were classified as no relapses before pregnancy but did not contribute to ARRs before symptom onset. One woman who did not breastfeed was excluded from early resumption of DMT analyses because she left Kaiser Permanente within 2 months postpartum.

The mean values and SDs of normally distributed variables were compared using 2-sample t tests; for variables with nonnormal distributions, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used; and for binary or categorical variables, the χ2 with the Fisher exact test was used. Statistical significance was set at p = 0.05. No adjustment for multiple comparisons was made. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Data availability

Due to review boards' policies, data would be available upon reasonable request.

Results

Patient characteristics and disease course during pregnancy and postpartum period

Four hundred sixty-six pregnancies occurred among 375 women during the study period. General characteristics of the women at the onset of each pregnancy are presented in table 1. Most women had relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS, 83.5%), 54.7% had at least 1 relapse within 2 years before pregnancy, 39.9% had MS-related disability, and 67.2% had suboptimally controlled disease at pregnancy onset. The majority (70.1%) had been treated with a DMT at some point since diagnosis, but 48.4% had discontinued treatment at least 1 year before pregnancy. Of those pregnancies exposed to DMT in the year before pregnancy, the majority (93.7%) used IFN-beta or GLAT. Only 13 women were treated with highly effective DMTs before pregnancy. Of the 51.6% of women who used DMTs in the year before pregnancy, half (n = 119, 25.8%) conceived while on treatment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women with MS at the onset of pregnancy

The average ARR declined during pregnancy compared with the 2 years before conception and returned to prepregnancy rates 4–6 months postpartum (table 2 and figure). There was no increase in the rate of relapse in the first 3 months postpartum in the entire cohort (figure) or in women with suboptimally controlled disease before pregnancy (figure). Even when women who breastfed exclusively were excluded from the suboptimally controlled disease analysis, no rebound increase in the ARR was observed in the first 3 months postpartum (0.56 and 0.47, p = 0.33, 2 years before pregnancy and 0–3 months postpartum, respectively). Most pregnancies (n = 343, 73.6%) were followed by a relapse-free postpartum year. However, 103 women experienced 1 relapse (22.1%), and 20 women (4.3%) experienced multiple relapses in the 12 months postpartum (table 3). Only 40 relapses occurred during pregnancy (table 3), 15 (37.5%) of which occurred in women who had stopped their DMT in the first/early second trimester or within 3 months before conception.

Table 2.

Pregnancy-related multiple sclerosis relapses

Figure. Average annualized relapse rate before, during, and after pregnancy.

Depicted is the average annualized relapse rate and 95% confidence intervals in the 2 years before pregnancy and each 3-month interval during (first, second, and third trimesters) and after pregnancy (PP = postpartum) in the entire cohort (A) and in the subgroup of women with suboptimally controlled disease at pregnancy onset (B). Relapse rates were higher in the suboptimally controlled group before and after pregnancy (B) compared with the entire cohort (A) but show a similar pattern of decline during pregnancy (p < 0.0001 for both groups) and return to prepregnancy rates between 4 and 6 months postpartum as in the entire cohort. No increased relapse rate is seen in the postpartum year compared with prepartum in either group.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of women with MS during pregnancy and the postpartum period

Predictors of postpartum relapses

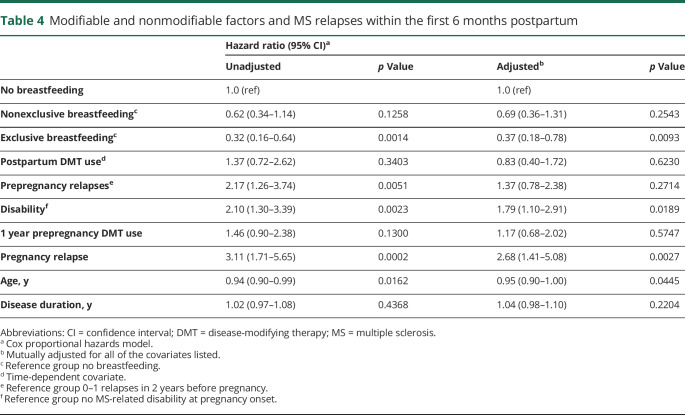

Table 4 shows the crude and adjusted HRs of predictors of relapses within the first 6 months postpartum. MS-related disability on neurologic examination before pregnancy and younger age was associated with an increased risk of relapses in the first 6 months postpartum and throughout the postpartum year (adjusted HR = 1.79, 95% CI = 1.22–2.60, p = 0.0026 for disability). Relapsing during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of early postpartum relapses, but the effect was not statistically significant through 12 months postpartum (adjusted HR = 1.68, 95% CI = 0.90–3.14, p = 0.1023 for pregnancy relapse). A high relapse frequency preceding pregnancy was associated with relapse throughout the postpartum year (adjusted HR = 1.64, 95% CI = 1.07–2.51, p = 0.0227) but not within the first 6 months (table 4).

Table 4.

Modifiable and nonmodifiable factors and MS relapses within the first 6 months postpartum

Breastfeeding

Most (87.3%) women breastfed their infants, and 35.8% breastfed exclusively for at least 2 months. The total duration of breastfeeding was significantly shorter in women who introduced supplemental feedings within the first 2 months postpartum compared with those who breastfed exclusively (median 2.3 months, interquartile range [IQR] = 0.7–6.1 vs 9.2 months, IQR = 6.0–12.4 months; p < 0.0001, respectively). The introduction of supplemental feedings occurred very early in this group compared with those who breastfed exclusively (median 0.0 months, IQR = 0.0–0.5 vs 6.0 months, IQR = 4.0–6.2 months; p < 0.0001, respectively).

Women who breastfed exclusively had fewer relapses (n = 15, 8.98%) in the first 6 months postpartum compared with those who breastfed nonexclusively (n = 41, 17.1%) or not at all (n = 15, 25.4%, p = 0.0054). Exclusive breastfeeding significantly reduced the risk of postpartum relapses (table 4, PS-adjusted HR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.15–0.69, p = 0.0032) but not nonexclusive breastfeeding (PS-adjusted HR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.34–1.14; p = 0.1243) compared with no breastfeeding (reference group). Exclusive breastfeeding was similarly protective in women with suboptimally controlled disease activity at pregnancy onset (adjusted HR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.18–0.83, p = 0.0154; p trend = 0.0424), and breastfeeding nonexclusively was not (adjusted HR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.35–1.40, p = 0.3115) compared with no breastfeeding (reference group).

During the second half of the postpartum year, the proportion of women who had their first postpartum relapse was very similar among women who breastfed exclusively for at least the first 2 months postpartum (n = 17, 10.2%), those who breastfed nonexclusively (n = 29, 12.1%), and those who did not breastfeed (n = 6, 10.2%).

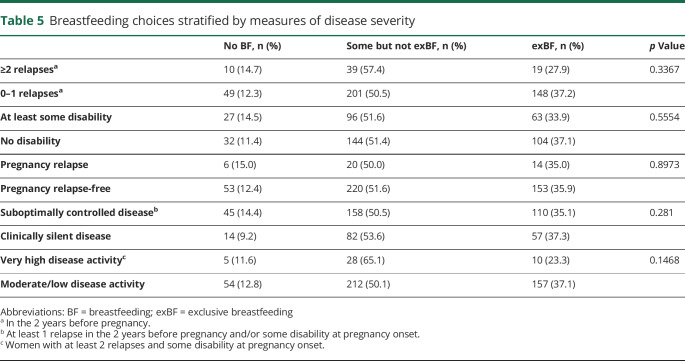

The only significant predictor of breastfeeding choices was use of DMT in the year before pregnancy. These women were less likely to breastfeed exclusively (crude odds ratio [OR] = 0.61, 95% CI = 0.41–0.89, p = 0.0105; adjusted OR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.43 to 0.94, p = 0.0242) but not less likely to have postpartum relapses (table 4) compared with those not using DMTs. Age, disease duration, disability, prepregnancy relapse frequency, and relapses during pregnancy were not associated with breastfeeding choices (table 5).

Table 5.

Breastfeeding choices stratified by measures of disease severity

MS DMT use

MS DMTs were resumed during the postpartum year in 41.2% of pregnancies (table 3). Of the women with postpartum relapses, 45 (36.6%) waited until after their first postpartum relapse to resume DMTs. DMT use and breastfeeding were not mutually exclusive. Sixty women resumed DMTs while breastfeeding, 11 within the first 2 months postpartum while breastfeeding exclusively, and an additional 35 women who breastfed exclusively resumed DMTs later in the postpartum year.

DMT use during the postpartum year, modeled as a time-dependent covariate, had no effect on the risk of postpartum relapses during the first 6 months (table 4) or the entire postpartum year (adjusted HR = 0.89, 95% CI = 0.56–1.43, p = 0.63).

Seventy-eight (16.7%) women resumed DMTs within 2 months postpartum, but 2 did not until after their first postpartum relapse. Twelve women (15.8%) who resumed DMTs within 2 months relapsed within 6 months and 25 (32.9%) within 12 months postpartum compared with 15.2% and 25.1%, respectively, among those who did not.

Most women who resumed a DMT within 2 months postpartum were on a DMT in the year before pregnancy (n = 74, 94.9%) and many at the time of conception (n = 43, 55.1%). Other factors that predicted early DMT use were relapses during pregnancy and disability at pregnancy onset, whereas intent to breastfeed reduced the likelihood of early DMT use (data not shown). DMT use within 2 months postpartum was not associated with a reduced risk of postpartum relapses during the 12 months postpartum even after taking into account these factors (PS-adjusted HR = 1.07, 95% CI = 0.65–1.76, p = 0.81, data not shown).

Discussion

For the past 20 years, women with MS have been counseled that the risk of relapse declines during pregnancy yet increases during the first few months postpartum before returning to prepregnancy rates later in the postpartum year. How to minimize this risk of postpartum relapses has been the subject of much debate. Until recently, all MS DMTs were considered incompatible with pregnancy and breastfeeding, and women with MS often chose to forego breastfeeding and resume DMTs or breastfeed and remain untreated. This clinical dilemma intensified as the evidence has mounted that prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding has significant infant and maternal health benefits, including studies suggesting that exclusive breastfeeding may reduce the risk of postpartum MS relapses.4,6

In our large contemporary, population-based cohort, we found a decreased relapse rate during pregnancy but no increased rate during the postpartum year compared with the prepregnancy period. Most women were relapse-free during the postpartum year, although most breastfed and less than half used DMTs. The increase in breastfeeding rates, including women with more severe MS disease activity before pregnancy, coincides with system-wide efforts to encourage all women to breastfeed their babies exclusively. Breastfeeding exclusively was associated with a reduced risk of postpartum relapses in the first 6 months postpartum even in women with suboptimally controlled disease before pregnancy. Breastfeeding choices were not significantly influenced by prepregnancy disease severity or pregnancy relapses. In contrast, postpartum use of the modestly effective DMTs, IFN-beta or GLAT, had no effect on risk of relapse in the postpartum year, even if treatment was started within 2 months. The finding from our study indicates that the fear of an increased risk of postpartum relapse no longer applies to most women with MS today, particularly in women who breastfeed exclusively.

Despite this absence of rebound disease activity postpartum, we were surprised to see that 67% of women had suboptimally controlled disease entering pregnancy and concerned that very few had been treated with highly effective DMTs. This is particularly troubling because this and previous studies1,2,15,16 have shown that measures of disease severity including prepregnancy relapse rate, MS-related disability, and relapses during pregnancy are independent predictors of postpartum relapses. In addition, MS-related disability is a measure of incomplete relapse recovery in this population, a predictor of poor long-term prognosis.17 Thus, although exclusive breastfeeding reduced the risk of postpartum relapses in these women with active MS before pregnancy and should be encouraged for multiple reasons, optimizing disease control before and after pregnancy is also essential. These findings led to the development and implementation of a pregnancy-specific MS treatment algorithm in KPSC described in detail elsewhere.18 Briefly, we now treat women with active disease and/or neurologic disability with a highly effective DMT with a prolonged duration of action (rituximab) before pregnancy, hold infusions during pregnancy, and resume infusions typically 6–12 months postpartum or sooner if indicated or desired by the mother. We consider rituximab and other monoclonal antibody DMTs, along with IFN-beta and GLAT, to be compatible with lactation18 and encourage women to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months and continue breastfeeding thereafter per their preferences.

Our recommendation that women with MS breastfeed exclusively extends beyond the potential beneficial effects of reducing postpartum MS relapse risk. There is extensive evidence pointing to a plethora of infant and maternal health benefits with breastfeeding, particularly prolonged or exclusive breastfeeding. These benefits include a decreased risk of infections, lower infectious mortality, and improved intelligence in the offspring compared with infants with short duration of breastfeeding or those who are not breastfed at all.19 These effects create inequalities that persist into adulthood. Maternal health benefits include a decreased risk of breast and ovarian cancers, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.20,21 It is these benefits and others not listed here that have led the World Health Organization and American Academy of Pediatrics to recommend exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months. A recent meta-analysis19 concluded that “the scaling up of breastfeeding to a near universal level could prevent 823,000 annual deaths in children younger than 5 years and 20,000 annual deaths from breast cancer.”

We contrast these striking benefits of breastfeeding with the common practice of telling women with MS to forego exclusive/prolonged breastfeeding to resume DMTs, although there is no evidence that breastfeeding harms them, even in previous studies in which breastfeeding, particularly exclusively, meant foregoing DMTs.4–6 Our study provides additional evidence that exclusive breastfeeding may even reduce the risk of postpartum MS relapses (with or without resuming DMTs). Thus, we reason that continuing to recommend that women with MS forego exclusive breastfeeding to resume MS DMTs that are incompatible with lactation is overly conservative and likely harmful to the infant's and mother's health.

The findings from this study are consistent with our previously reported findings that exclusive breastfeeding seems to reduce the risk of postpartum relapse4,6 in the first but not second half of the postpartum year, acting like a treatment with a natural end date when the infant begins regular supplemental feedings,4 typically between 4 and 8 months of age. Our findings are also consistent with previous studies that examined some but not necessarily exclusive breastfeeding and found no association with postpartum relapse risk1,5 or marginal benefit9 when considering the entire postpartum year.

We found no evidence that confounding by indication (women with higher disease activity are less likely to breastfeed exclusively and have a higher risk of postpartum relapses) is a better explanation of our findings. There was no significant association between breastfeeding choices and measures of disease severity. We found consistent protective associations using multiple statistical methods and found that exclusive breastfeeding was also highly protective in women with suboptimally controlled disease at pregnancy onset, whose prepregnancy ARR approached that of the historical cohort (ARR 95% CI = 0.60–0.801). In addition, the magnitude of effect is large enough that it is unlikely to be explained by residual or unmeasured confounding.22 Only the behavioral choice of using DMTs in the year before pregnancy, which had no impact on the risk of postpartum relapses, was associated with a decreased likelihood of breastfeeding exclusively and an increased likelihood of resuming DMTs. PS-adjusted models taking this nonconfounding association into account continued to show a benefit of exclusive breastfeeding. Like other studies, we found no increased risk of postpartum relapses in women who breastfed even in lieu of resuming DMTs.

In contrast, we found no evidence that starting modestly effective DMTs during the postpartum year, even within 2 months after delivery, reduces the risk of postpartum relapses. Previous studies of postpartum DMT use and relapses found either no effect when resumed within 2 weeks3 or 1 month4 or a nonsignificant reduction later in the postpartum years when resumed within 3 months.2 These studies were limited by selection2,4 and referral center bias2,4 and did not include patients with CIS,2–4 resulting in participants with more active disease before, during, and after pregnancy than seen in our population. All studies, including this one, are limited by relatively few women resuming DMTs early in the postpartum year.

Our population was more mildly affected when compared with historical studies.1,23 The women in our study had significantly lower ARRs before and after pregnancy (0.37) compared with the historical MS and pregnancy cohort (0.71) from which the counseling recommendations stem. Women in our study also had fewer relapses during pregnancy and in the postpartum period compared with more recent referral center2,7,8 and registry4 studies. These differences are most likely due to changes in MS diagnostic criteria and lack of referral center bias in our population.

The historical cohort1 was recruited from referral centers at a time when MS diagnostic criteria required 2 clinical relapses and breastfeeding rates were low. Since then, MS diagnostic criteria have been revised to require only 1 clinical relapse and rely heavily on MRI findings. The 2017 criteria classify many patients previously designated as CIS, including all of those included in this study, as MS. These changes have led to earlier MS diagnosis and diagnosis of milder cases. This is reflected nicely in the marked decline in ARRs observed in the placebo arms of randomized controlled trials from 0.8423 to 0.3624 when using the revised diagnostic criteria. Thus, it is not surprising that our patients had fewer prepregnancy relapses than the historical cohort1 or other cohorts that excluded patients with CIS.2,4

Another change is the now common use of MS DMTs and availability of highly effective DMTs. However, we believe that DMT use alone is an unsatisfactory explanation for our more mildly affected population, as the prepregnancy relapse rates we observed are very similar to the placebo arms of contemporary RRMS RCTs.24 In addition, very few women were treated with highly effective DMTs, and many women were untreated before pregnancy.

The lack of an increased relapse rate and even slight suppression in the first 3 months postpartum we observed is most likely due to the high rates of breastfeeding, particularly exclusive breastfeeding. This is supported by the multiple sensitivity analyses we conducted that continue to demonstrate a lack of postpartum rebound relapses and a beneficial effect of breastfeeding exclusively even in women with more active disease before pregnancy. However, even when we focused on the women with suboptimally controlled disease at pregnancy onset and excluded those who breastfed exclusively for 2 months or more, we still did not observe any early postpartum rebound disease activity. This could be due to a time-dependent beneficial effect of breastfeeding or differences in capturing postpartum relapses. The historical cohort study1 collected prepregnancy relapses from routine medical records like we did, but prospectively collected postpartum relapses, while we relied on routine medical records, a method that is likely to underreport mild relapses. These limitations are currently under investigation in a prospective cohort study.

Our findings also differ from a recently published database study16 and a referral center study,8 which reported rebound disease activity in the postpartum period. The database study reported prepregnancy relapse rates similar to ours,16 but the results of both studies are difficult to interpret because of large amounts of missing data,16 selection and referral center bias,8,16 inability to account for breastfeeding choices,16 and pregnancies spanning 1967–201016 or 1993–2015.8 Other recent MS and pregnancy studies did not report relapse rates,2,4 making it unclear whether rebound postpartum disease activity was observed.

Few women in our study were treated with natalizumab or fingolimod before pregnancy; therefore, this study does not address the potential harms of drug cessation or benefits of breastfeeding on postpartum MS relapses, if any, in these patients. Future studies to address this subgroup of women are needed as severe drug cessation relapses during pregnancy have been reported.25,26 Other limitations of this study include reliance on routinely collected medical records to assess relapses and disease activity. This undercounting of mild relapses before, during, and after pregnancy and misclassifying patients as optimally controlled because MRIs were rarely ordered postpartum and usually only when relapses occurred. In addition, we could not examine exclusive breastfeeding as a time-dependent covariate, as precise breastfeeding stop dates after 2 months postpartum are rarely recorded. We cannot exclude a small, delayed benefit of IFN-beta or GLAT treatment, particularly in women who concomitantly breastfeed. These limitations should be addressed in future studies.

Strengths of this study are a large, population-based sample, representative of women diagnosed with MS now and comprehensive medical records of the mother and infant, allowing unbiased assessment of clinical variables, breast and formula feeding. Unlike previous studies,4–6 breastfeeding and DMT use were not mutually exclusive, allowing us to examine these factors simultaneously.

Taken together, our findings indicate that most women diagnosed with MS today can have children and breastfeed without incurring an increased risk of relapses during the postpartum period. Women with MS should be encouraged to breastfeed exclusively, and those with active disease before pregnancy and/or incomplete recovery from previous relapses should optimize their MS DMT before conception. Women who are considering foregoing breastfeeding to resume modestly effective DMTs should be informed that there is no evidence that these DMTs will reduce the risk of postpartum relapses and counseled about the general health benefits of breastfeeding.

Glossary

- ARR

annualized relapse rate

- cEHR

complete electronic health record

- CI

confidence interval

- CIS

clinically isolated syndrome

- DMT

disease-modifying therapy

- EHR

electronic health record

- GLAT

glatiramer acetate

- HR

hazard ratio

- IFN-beta

interferon-beta

- IQR

interquartile range

- KPNC

Kaiser Permanente Northern California

- KPSC

Kaiser Permanente Southern California

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- OR

odds ratio

- PS

propensity score

- RRMS

relapsing-remitting MS

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Editorial, page 769

Study funding

This study was supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (RG4809-A, PI: Langer-Gould). The funding sponsor had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Disclosure

A. Langer-Gould has received grant support and awards from the NIH, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and the National MS Society. She currently serves as a voting member on the California Technology Assessment Forum, a core program of the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). She has received sponsored and reimbursed travel from the ICER. J. Smith, K. Albers, A. Xiang, J. Wu, E. Kerezsi, K. McClearnen, E. Gonzales, A. Leimpeter, and S. Van Den Eeden report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Confavreux C, Hutchinson M, Hours MM, Cortinovis-Tourniaire P, Moreau T. Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis Group. N Engl J Med 1998;339:285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Portaccio E, Ghezzi A, Hakiki B, et al. Postpartum relapses increase the risk of disability progression in multiple sclerosis: the role of disease modifying drugs. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:845–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaber BE, Chi MD, Brara SM, Zhang JL, Langer-Gould AM. Immunomodulatory agents and risk of postpartum multiple sclerosis relapses. Perm J 2014;18:9–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hellwig K, Rockhoff M, Herbstritt S, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding and the effect on postpartum multiple sclerosis relapses. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:1132–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Portaccio E, Ghezzi A, Hakiki B, et al. Breastfeeding is not related to postpartum relapses in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2011;77:145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langer-Gould A, Huang SM, Gupta R, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding and the risk of postpartum relapses in women with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2009;66:958–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Airas L, Jalkanen A, Alanen A, Pirttila T, Marttila RJ. Breast-feeding, postpartum and prepregnancy disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2010;75:474–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jesus-Ribeiro J, Correia I, Martins AI, et al. Pregnancy in multiple sclerosis: a Portuguese cohort study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2017;17:63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson LM, Franklin GM, Jones MC. Risk of multiple sclerosis exacerbation during pregnancy and breast-feeding. JAMA 1988;259:3441–3443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulick EE, Halper J. Influence of infant feeding method on postpartum relapse of mothers with MS. Int J MS Care 2002;4:183–191. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pakpoor J, Disanto G, Lacey MV, Hellwig K, Giovannoni G, Ramagopalan SV. Breastfeeding and multiple sclerosis relapses: a meta-analysis. J Neurol 2012;259:2246–2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langer-Gould A, Brara SM, Beaber BE, Zhang JL. The incidence of clinically isolated syndrome in a multi-ethnic cohort. J Neurol 2014;261:1349–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koebnick C, Langer-Gould AM, Gould MK, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: comparison with US Census Bureau data. Perm J 2012;16:37–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vukusic S, Hutchinson M, Hours M, et al. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): clinical predictors of post-partum relapse. Brain 2004;127:1353–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes SE, Spelman T, Gray OM, et al. Predictors and dynamics of postpartum relapses in women with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2014;20:739–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langer-Gould A, Popat RA, Huang SM, et al. Clinical and demographic predictors of long-term disability in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Arch Neurol 2006;63:1686–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langer-Gould AM. Pregnancy and family planning in multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2019;25:773–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016;387:475–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunderson EP, Jacobs DR Jr, Chiang V, et al. Duration of lactation and incidence of the metabolic syndrome in women of reproductive age according to gestational diabetes mellitus status: a 20-year prospective study in CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults). Diabetes 2010;59:495–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuebe AM, Rich-Edwards JW, Willett WC, Manson JE, Michels KB. Duration of lactation and incidence of type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2005;294:2601–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Psaty BM, Koepsell TD, Lin D, et al. Assessment and control for confounding by indication in observational studies. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:749–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson KP, Brooks BR, Cohen JA, et al. Copolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a phase III multicenter, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. The Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Neurology 1995;45:1268–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1098–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haghikia A, Langer-Gould A, Rellensmann G, et al. Natalizumab use during the third trimester of pregnancy. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:891–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hemat S, Houtchens M, Vidal-Jordana A, et al. . Disease activity during pregnancy after fingolimod withdrawal due to planning a pregnancy in women with multiple sclerosis. Poster presented at 70th American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting; April 21–27, 2018; Los Angeles, CA. ECTRIMS Online Library.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to review boards' policies, data would be available upon reasonable request.