Abstract

Differential transcriptome analysis is an effective method for gene selection of triterpene saponin biosynthetic pathways. MeJA-induced differential transcriptome of Panax notoginseng has not been analyzed yet. In this study, comparative transcriptome analysis of P. notoginseng roots and methyl jasmonate (MeJA)-induced roots revealed 83,532 assembled unigenes and 21,947 differentially expressed unigenes. Sixteen AP2/ERF transcription factors, which were significantly induced by MeJA treatment in the root of P. notoginseng, were selected for further analysis. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and co-expression network analysis of the 16 AP2/ERF transcription factors showed that PnERF2 and PnERF3 had significant correlation with dammarenediol II synthase gene (DS) and squalene epoxidase gene (SE), which are key genes in notoginsenoside biosynthesis, in different tissues and MeJA-induced roots. A phylogenetic tree was conducted to analyze the 16 candidate AP2/ERF transcription factors and other 38 transcription factors. The phylogenetic tree analysis showed PnERF2, AtERF3, AtERF7, TcERF12 and other seven transcriptional factors are in same branch, while PnERF3 had close evolutionary relationships with AtDREB1A, GhERF38 and TcAP2. The results of comparative transcriptomes and AP2/ERF transcriptional factors analysis laid a solid foundation for further investigations of disease resistance and notoginsenoside biosynthesis in P. notoginseng.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-020-02246-w) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: AP2/ERF transcription factors, Transcriptome, Panax notoginseng, Methyl jasmonate, Real-time quantitative PCR, Co-expression analysis

Introduction

Panax notoginseng (P. notoginseng), a well-known and highly valued Chinese medicinal herb, has been used for medicinal herb more than 600 years in China (Wang et al. 2006). The root of P. notoginseng, which is the main medicinal part, is normally harvested in autumn after three years’ growth (Fig. S1). As a species of the Ginseng genus, the main active constituents of P. notoginseng are notoginsenosides, which are triterpene saponins (Qiao et al. 2018). A wide range of pharmacological activities by notoginsenosides have been reported including hemostatic, anti-oxidant, hepatoprotective and anti-cancer functions (Nag et al. 2012; Leung and Wong 2010; Jovanovski et al. 2010; Karmazyn and Gan 2017; Liu et al. 2018). As a perennial herbaceous plant, the roots of P. notoginseng are harvested as a crude drug. However, the roots of P. notoginseng are easily infected by pests and diseases, which limit the commercialization of P. notoginseng greatly (Zhang et al. 2010).

Jasmonates (JAs) [jasmonic acid (JA) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA)] are important signal molecules that globally regulate the production of multiple primary and secondary metabolites in plants (Fits and Van der Memelink 2000; Qi et al. 2018; Gu et al. 2012). Compared with other elicitors, JAs are effective at stimulating the biosynthesis of notoginsenosides in P. notoginseng (Niu et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2015). The AP2/ERF transcription factors, one of the most important families involved in plant, response to biotic and abiotic stresses, as well as the regulation of metabolic and developmental processes in various plant species (Du et al. 2016; Yu et al. 2012). The overexpression of the jasmonate-responsive AP2/ERF transcriptional regulator AaORA and AaERF1 could significantly enhance disease resistance and the accumulation of artemisinin in A. annua (Yu et al. 2012; Lu et al. 2013a, b).

In this study, transcriptome databases of roots and MeJA-induced roots from 3-year-old P. notoginseng were established using next generation sequencing technology. A comparative transcriptome analysis revealed differentially expressed genes between roots and MeJA-induced roots in P. notoginseng. Among the 166 AP2/ERF transcription factors obtained from comparative transcriptome analysis, 16 AP2/ERF transcription factors, which were significantly induced by MeJA treatment, were selected to further analysis. This study provided valuable information for the screening of key regulators to enhance disease resistance and notoginsenoside biosynthesis in P. notoginseng.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and MeJA treatment

Three-year-old P. notoginseng plants were taken from Wenshan Prefecture, Yunnan Province, China. To study the changes in gene expression levels after MeJA treatment, plants were treated with 1 mM MeJA. The leaves and stems were sprayed with 100 ml MeJA (1 mM), while the roots were irrigated with another 100 ml MeJA (1 mM). The fibrous roots were collected before MeJA treatment (0 h) and at different time points (3 h and 6 h) after MeJA treatment. The fibrous roots from three plants were pooled for each sample, respectively. After cleaning with distilled water, all fibrous roots were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C until used.

RNA isolation, cDNA library construction and sequencing

The Plant RNA Isolation Kit (BioTeke, Beijing, China) was used for RNA isolation from the fibrous roots of P. notoginseng. The quantity and quality of total RNA were analyzed using a Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). High-quality (RNA integrity number ≥ 6.5) RNA was used. Illumina sequencing was performed at the Beijing Genomic Institute (Shenzhen, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, total RNA from the roots of P. notoginseng were prepared using poly(A) enrichment by poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads (Illumina). Poly(A) RNA was purified and converted into small fragments using a fragmentation buffer. Single-strand cDNAs were synthesized and sequenced using Illumina HiSeq™ 4000 sequencing technology (Illumina, USA). Sample sequencing and basic analytical processing such as base calling were performed according to manufacturer's protocol.

De novo assembly and annotation

Raw data in the FASTQ format were filtered to obtain high quality de novo transcriptome data (clean data). In this step, clean data were obtained by removing adapter sequence or low-quality reads from raw data. The transcriptome sequences were assembled using the short-read assembly program Trinity (Grabherr et al. 2011). Annotating transcripts were performed using the BLAST blastn algorithm against GenBank Nt (non-redundant nucleotide database, NCBI). The assembled unigenes were translated into amino acids and aligned with BLASTX (E value ≤ 10−5) to protein databases including Nr (non-redundant protein database, NCBI), Swiss-Prot, GO (gene ontology, https://www.geneontology.org/) and COG (clusters of orthologous groups). Each unigene was annotated with the highest similarity protein. Pathway assignments were determined using the KAAS-KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (https://www.genome.jp/tools/kaas/) (Moriya et al. 2007).

Screening and significance test for differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

Differential expression analysis was used to identify the DEGs between the transcriptome libraries of untreated (Root) and MeJA-treated P. notoginseng roots (Root-MJ-3 and Root-MJ-6). Using the method of digital gene expression profiling published by Audic and Claverie (Audic and Claverie 1997) and DESeq2 software, the DEGs among the libraries in response to the MeJA treatment were screened in accordance with strict algorithms. A random sampling model for hypothesis testing was then used to analyze the significance of differential expression genes. FDR ≤ 0.001 and fold change ≥ 2 of the DEGs were used as the thresholds to claim the statistical significance of differential gene expression. Fragments mapped per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped (FPKM) cutoff of 1 was used to calculate assigned unigene expression levels. A heat map of the FPKMs of 166 AP2/ERF transcription factors in untreated (Root) and MeJA-treated P. notoginseng roots was constructed with the software Multiple Experiment Viewer 4.9.0.

Phylogenetic analysis of significant differentially expressed AP2/ERF transcription factors

A subset of 16 full-length AP2/ERF transcription factors in P. notoginseng whose expression levels showed at least tenfold difference between roots and MeJA-induced roots were used for phylogenetic analysis (Table 2). A phylogenetic analysis of the 16 PnERFs, AtERFs from Arabidopsis and other species ERFs was carried out by alignment with Clustal W using default parameters. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 (Kumar et al. 2016) and decorated in Evolview (https://120.202.110.254:8280/evolview) (He et al. 2016). The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) is shown next to the branches. The evolutionary distances were computed using the p-distance method.

Table 2.

Significant differentially expressed AP2/ERF transcription factors in P. notoginseng

| Unigene | MJ-0-FPKM | MJ-3-FPKM | MJ-6-FPKM |

|---|---|---|---|

| PnERF1 | 6.46 | 77.58 | 114.07 |

| PnERF2 | 0.25 | 38.56 | 21.49 |

| PnERF3 | 0.55 | 65.56 | 33.9 |

| PnERF22 | 25.7 | 304.52 | 261.68 |

| PnERF36 | 0 | 65.31 | 53.82 |

| PnERF40 | 32.11 | 307.45 | 268.11 |

| PnERF76 | 4.24 | 20.61 | 211.49 |

| PnERF83 | 5.55 | 51.51 | 104.38 |

| PnERF92 | 5.57 | 110.35 | 184.02 |

| PnERF102 | 2.94 | 27.57 | 57.88 |

| PnERF117 | 14.5 | 253.06 | 230.83 |

| PnERF120 | 1.08 | 27.09 | 231.53 |

| PnERF130 | 3.84 | 35.37 | 56.42 |

| PnERF135 | 18.18 | 153.71 | 179.64 |

| PnERF148 | 0.11 | 10.2 | 33.07 |

| PnERF159 | 3.35 | 66.53 | 138.75 |

Sixteen significant differentially expressed AP2/ERF transcription factors were chosen from the in 166 AP2/ERF transcription factors in untreated roots and MeJA-induced roots of P. notoginseng based on the the expression levels. Sixteen AP2/ERF transcription factors were significantly induced by MeJA treatment

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis

The notoginsenoside biosynthesis key genes DS, SE and the 16 full-length PnERFs whose expression levels were significantly different between roots and MeJA-induced roots were analyzed using RT-qPCR method. All RNA samples were digested with DNase I (RNase-free) prior to use. Aliquots of 0.4 μg total RNA were employed in the reverse transcriptase reaction using random hexamer primers for the synthesis of first-strand cDNA. RT-qPCR amplification reactions were performed on a LightCycler® 96 Real-Time PCR System (Roche) with gene-specific primers, and the SYBR ExScript RT-qPCR kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan) protocol to confirm changes in gene expression. The thermal cycle conditions were 5 min at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of amplification (15 s at 95 °C, 15 s at 60 °C and 30 s at 72 °C). A melting curve analysis following each RT-qPCR was performed to assess product specificity. Expression patterns of these genes were analyzed in three biological replicates. Quantification of the target gene expression was carried out with comparative CT method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). All the primers used in RT-qPCR are listed in Table S1. The experiment of RT-qPCR follows MIQE precis and the RT-qPCR checklist listing the minimum technical information (Grabherr et al. 2011).

Results

Sequencing and de novo assembly

Complementary DNA (cDNA) libraries were constructed using total RNA extracted from roots and MeJA-treated roots of P. notoginseng. To generate transcriptome sequences, these prepared cDNA libraries were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeqTM 4000 platform. The results showed that after removing adapter sequence or low-quality reads from raw data, a total 13.8 Gb high quality nucleotide bases of roots and MeJA-treated roots of P. notoginseng were retained for further assembly. Velvet assembler was used to assemble the filtered reads into contigs, which generated 97,653, 94,821 and 95,335 contigs for P. notoginseng roots (Root), Root-MJ-3 and Root-MJ-6 samples, respectively. Oases-0.2.08 was used to generate unigenes, which resulted in 63,011, 61,464 and 62,994 unigenes for P. notoginseng root (Root), Root-MJ-3 and Root-MJ-6 samples, respectively. The mean lengths of unigenes were 988 bp, 970 bp and 966 bp, respectively. In total, 83,532 unigenes were assembled from all three transcriptomes together. A summary of sequencing and assembly results is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Statistics of de novo assembly

| Sample | Total number | Total length | Mean length | N50 | N70 | N90 | GC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root | 63,011 | 62,266,565 | 988 | 1620 | 1014 | 402 | 40.67 |

| Root-MJ-3 | 61,464 | 59,674,857 | 970 | 1578 | 991 | 399 | 40.73 |

| Root-MJ-6 | 62,994 | 60,896,542 | 966 | 1589 | 983 | 394 | 40.66 |

| All-unigene | 83,532 | 95,702,924 | 1145 | 1825 | 1216 | 510 | 40.38 |

Assembly results include total number, total length and mean length of unigenes in P. notoginseng root (Root), Root-MJ-3 and Root-MJ-6 samples was shown. Total number means the number of all unigenes which was de novo assembly from samples. The N50 is a statistic of a set of contigs’ length. N50, N70 or N90 is defined as the contig length such that equal or longer contigs produce 50%, 70% or 90% of all contigs’ length. The larger of the numbers, the better of the assemble effect

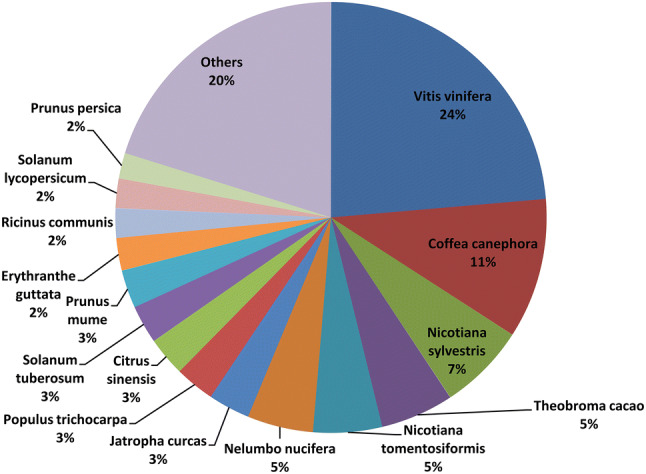

Functional annotation by searching against public databases

For functional annotation, the assembled unigenes were searched against the Nr database, the Swiss-Prot protein database, the Eukaryotic Orthologous Groups of proteins (COG) database, and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database with an E value threshold of 10–5. In total, 83,532 unigenes were annotated with 57,789 unique proteins. Out of those unigenes, 56,970 (68.20%), 54,508 (65.25%), 39,977 (47.86%), 22,429 (26.85%), 35,034 (41.94%), 26,160 (GO: 31.32%) and 40,727 (48.76%) unigenes showed significant similarity to known proteins in Nr, Nt, Swissprot, COG, KEGG, GO and Interpro databases, respectively. Most proteins (56,970 of 57,789) were annotated by the NR database. Of these, 13,414 BLASTX hits were matched to the proteins of Vitis vinifera. Only 5972, 3722, 3110 and 2839 BLASTX hits were aligned to NR proteins of Coffea canephora, Nicotiana sylvestris, Theobroma cacao and Nicotiana tomentosiformis, respectively (Fig. 1). Thus, P. notoginseng had a closer evolutionary relationship with V. vinifera.

Fig. 1.

Hit species distribution of BLASTx matches of P. notoginseng unigenes against NCBI Nr database

Overview of unigene classification

To obtain more information from the predicted P. notoginseng unigenes, GO, Eukaryotic Orthologous Groups of proteins (KOG) and KEGG databases were used to perform functional classification analysis. With NR annotation, Blast2GO program (Conesa et al. 2005) was used to obtain GO annotation of the predicted unigenes. Then, WEGO software (Ye et al. 2006) was used to perform GO functional classification for all unigenes. In total, 26,160 unigenes of P. notoginseng with BLAST matches to known proteins were assigned to 3 main GO categories. These GO terms were further subdivided into 56 sub-categories (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Histogram showing gene ontology (GO) functional classification analysis of P. notoginseng unigenes. All unigenes of P. notoginseng were assigned to three main GO categories. These GO terms were further subdivided into 56 sub-categories. Left Y axis shows GO functions and the right Y axis shows the three main GO categories: biological process, cellular components and molecular function. The X axis shows the number of genes which have the GO function

Within the P. notoginseng unigene set, 22,429 unigenes were categorized (E value ≤ 10–5) in 25 functional COG clusters (Fig. 3). Thus, only a small proportion of the unigenes (26.9%) had protein domains with annotations for COG categories. The five largest categories were: (1) general function predictions only (7119, 31.7%); (2) transcription (3957, 17.6%); (3) replication, recombination and repair (3797, 16.9%); (4) posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones (2978, 13.3%); and (5) signal transduction mechanisms (2944, 13.1%). To further analyze the transcriptome of P. notoginseng, all unigenes were analyzed in the KEGG pathway database. Based on a comparison against the KEGG database using BLASTX with an E value threshold of 10–5, 35,034 (41.7%) sequences of 83,532 unigenes were found to have significant matches in the database and were assigned to 25 functional KEGG clusters including 126 KEGG pathways (Fig. S2). The KEGG pathways contain all the process of the plant’s life such as primary metabolism, secondary metabolism and signal transduction. Besides, metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides pathways have 639 genes, while biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites pathways have 825 genes among the KEGG pathways.

Fig. 3.

Histogram showing clusters of orthologous groups (COG) functional analysis of P. notoginseng unigenes. The unigenes were categorized in 5 largest categories and 25 functional COG clusters. COG functions are showed in Y axis. The X axis are the corresponding number of genes which have the GO function

DEGs after MeJA treatment

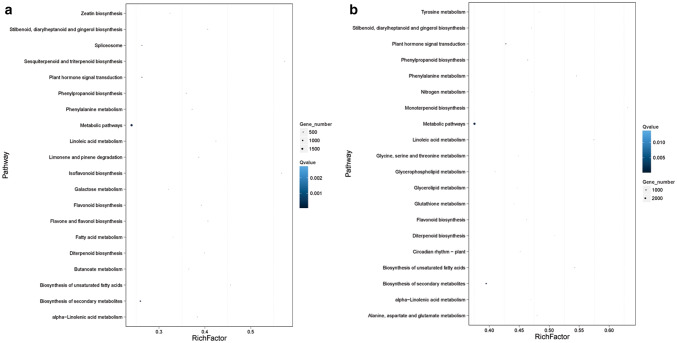

The significantly DEGs at each time point after MeJA treatment were considered as regulated genes of MeJA (Fig. 4 and Fig. S3). The differential expressions after the treatment of MeJA between Root and Root-MJ-3 identified a total of 13,699 DEGs. Among these significant DEGs, 6769 (49.4%) DEGs showed upregulated expression levels, whereas the other 6930 (50.6%) showed downregulated expression levels. The differential expression due to MeJA treatment between Root and Root-MJ-6 identified a total of 21,947 DEGs. Among those significant DEGs, 9936 (49.3%) showed upregulated expression levels, whereas the other 12,011 (50.7%) showed downregulated expression levels. Pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs showed that the pathways which are significantly enriched in response to MeJA treatment (Fig. 5). In the 20 significant pathways, metabolic pathways had the most DEGs after MeJA treatment, followed by the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites and plant hormone signal transduction.

Fig. 4.

Scatter plots and histogram of differentially expressed genes significantly different between roots and MeJA-induced roots. a Volcano-plot map of DEGs. The genes were classified into three classes. Red genes are upregulated, blue genes are downregulated and black genes are not differentially expressed genes. The X axis is the significant index with a − log10 conversion, and the Y axis shows the difference multiple value with a log2 conversion. b Histogram of the DEGs amount. The X axis is the name of compared samples, and the Y axis shows the corresponding number of DEGs. The red bar is upregulated genes, and the blue bar is downregulated genes

Fig. 5.

Pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs between a untreated roots and MeJA-3 roots, b untreated roots and MeJA-6 roots. The X axis is the q value of the enrichment factor and the Y axis are the pathway names. The color represents the q value of the enrichment factor. The size of the point shows DEG numbers

By screening the putative 57,789 proteins with the AP2/ERF family domain model (AP2, PF00847), 166 AP2/ERF transcription factors were identified by Hmmer 3.0 with AP2/ERF family domain model (AP2, PF00847). With analyzing of the expression levels of all the 166 AP2/ERF transcription factors in RNA-seq (Fig. 6), we found that 16 AP2/ERF transcription factors were significantly induced by MeJA treatment, which were selected to further analysis (Table 2). The significant differential AP2/ERF transcription factors should satisfy the following two conditions. First, after MeJA induction, the FPKM value of gene expression was more than 10 at two time points of Root-MJ-3 and Root-MJ-6. Second, the difference expression genes were at least five times at two time points of Root-MJ-3 and Root-MJ-6. Sixteen significant differential AP2/ERF transcription factors were chosen for further RT-PCR experiment.

Fig. 6.

Heatmap of the expression levels of 166 AP2/ERF transcription factors in untreated roots and MeJA-induced roots of P. notoginseng. The expression patterns heatmap of 166 AP2/ERF transcription factors were generated by MEV with green-black-red scheme

Identification and expression analysis of AP2/ERF transcription factors related to notoginsenoside biosynthesis

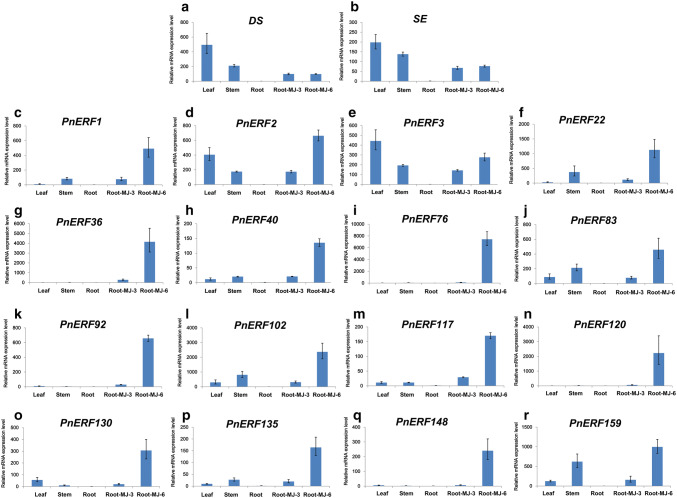

To identify potential AP2/ERF transcription factor candidates involved in notoginsenoside biosynthesis, the expression levels of key genes in notoginsenoside biosynthesis, DS, SE and 16 AP2/ERF transcription factors of P. notoginseng were measured in the leaves, stems, roots of untreated and MeJA-induced plants by RT-qPCR. The Key genes in notoginsenoside biosynthesis, DS and SE, were highly expressed in the leaves (Leaf), lower in the stems (Stem) and poorly expressed in the roots (Root). In responding to the MeJA treatment, the transcript levels of DS and SE were increased rapidly within 3 h (h), whereas the transcripts were similar and not rapidly decreased within 6 h after MeJA treatment (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Expression patterns of 16 P. notoginseng ethylene-response factors (PnERFs), DS and SE in P. notoginseng. Error bars are standard error (n = 3). PnActin was used as a control for normalization. The data of the histogram came from RT-qPCR performed on a LightCycler® 96 Real-Time PCR System

Among these 16 AP2/ERF transcription factors, the expression patterns of PnERF2 and PnERF3 were similar to those of DS and SE. Other AP2/ERF transcription factors had much greater different expression patterns (Fig. 7). PnERF76, PnERF92, PnERF148, PnERF120 and PnERF36 were poorly expressed in the leaves and stems. The expression levels of PnERF102, PnERF159, PnERF83, PnERF22, PnERF40, PnERF117, PnERF135 and PnERF131 in the stems were much higher than the expression levels in the leaves, which had much different expression patterns than those of DS and SE (Fig. 7).

To provide evidence to show these transcription factors participate in the notoginsenosides biosynthesis, gene co-expression network analysis were performed between 16 PnERFs, DS and SE (showed in Fig. 8). After a Pearson correlation coefficients analysis of 16 PnERFs, DS and SE in SPSS Statistic 22, the result indicated that PnERF2 and PnERF3 show a significant correlation with DS and SE genes. It provides a further evidence to show these two transcription factor could participate in the notoginsenosides biosynthesis. The results of the Pearson correlation coefficients analysis showed at Table S2 in Supplementary Materials. And a visual result showed their correlation by cytoscape 3.6.1 (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Gene co-expression network analysis between 16 PnERFs, DS and SE. Expression patterns of 16 P. notoginseng ethylene-response factors (PnERFs), DS and SE in P. notoginseng were employed to reflect their relationship in Co-express network. The gene co-expression network analysis generate by SPSS Statistic 22 and cytoscape 3.6.1. The red lines show positive correlation, blue lines show negative correlation, and white lines have not a significant correlation

Phylogenetic analysis of AP2/ERF transcription factors in P. notoginseng

The proteins of 16 AP2/ERF transcription factors in P. notoginseng, 18 AP2/ERF transcription factors in Arabidopsis and 20 AP2/ERF transcription factors in other species were used to construct a phylogenetic tree. The constructed phylogenetic trees showed that these AP2/ERF transcription factors formed several evolutionary branches (Fig. 9). PnERF1, PnERF2, PnERF3 and PnERF135 are separated into different twig of the phylogenetic tree. PnERF1, a transcription factor of P. notoginseng, was cloned and been characterized to be a positive regulator related to triterpenoid saponin biosynthesis in P. notoginseng (Deng et al. 2017). In addition, PnERF2, AtERF3, AtERF7, TcERF12 and other seven transcription factors are in same branch. PnERF3 had close evolutionary relationships with AtDREB1A, GhERF38 and TcAP2. PnERF102, PnERF159, PnERF83, PnERF130 and AtRAV formed a close evolutionary branch. Phylogenetic analysis further revealed that PnERF22, PnERF117 and PnERF40 has close evolutionary relationships to GbEREB1, GhERF5, AtERF2, AaERF1 and NtERF32, and may play key roles in disease resistance in P. notoginseng.

Fig. 9.

Phylogenetic analysis of 16 PnERFs from P. notoginseng transcriptome with 38 previously published AP2/ERF transcription factors from various species. Evolutionary analysis was conducted in MEGA7 and decorated in Evolview (https://120.202.110.254:8280/evolview). The phylogenetic tree was generated by the neighbor-joining method, and the numbers on the branches represent bootstrap supported for 1000 replicates. The AP2/ERF transcription factors used in the phylogenetic tree analysis were from P. notoginseng PnERF1 (CL2335.Contig1, KY817607), PnERF36 (CL5499.Contig1, KY817608), PnERF102 (CL5734.Contig1, KY817609), PnERF159 (CL5734.Contig2, KY817610), PnERF83 (CL5734.Contig3, KY817611), PnERF22 (CL8518.Contig1, KY817612), PnERF40 (CL8518.Contig3, KY362759), PnERF76 (Unigene3088, KY817613), PnERF92 (Unigene4336, KY362757), PnERF148 (Unigene7002, KY817614), PnERF2 (Unigene9505, KY362754), PnERF120 (Unigene10626, KY817615), PnERF117 (Unigene11285, KY362756), PnERF135 (Unigene20308, KY817616), PnERF2 (Unigene20902, KY362758), PnERF130 (Unigene22697, KY817617); Arabidopsis thaliana AtERF1 (NM113225), AtERF2 (NM124093), AtERF3 (NM103946), AtERF4 (NM112384), AtERF5 (NM124094), AtERF6 (AB013301), AtERF7 (AB032201), AtERF8 (AB036884), AtERF9 (AB047648), AtERF10 (AB047649) and ORA59 (NM100497), AaERF1 (AEQ93554.1), AaERF2 (AEQ93555.1), AaORA (AGB07586.1), AtDREB1A (NP_567720.1), AtERF104 (Q9FKG1.1), AtERF14 (AEE27689.1), AtERF96 (Q9LSX0.1), AtERF98 (Q9LTC5.1), AtRAV1 (BAA34250.1), AtWIND1 (NP_177931.1), ORCA1 (CAB93939.1), ORCA2 (CAB93940.1), ORCA3 (ABW77571.1), GbEREB1 (ABN50365.2), GhDBP2 (AAT39542.1), GhERF1 (AAO59439.1), GhERF38 (ARB50223.1), GhERF4 (AAX07461.1), GhERF5 (AAX07459.1), HbERF1 (AFX83939.1), NtERF32 (BAN58170.1), NtTSI1 (AAC14323.1), SmERF128 (QBA30207.1), TcAP2 (ACB30551.1), TcDREB (ACB30552.1), TcERF12 (ALJ11035.1), and TcERF15 (ALJ11036.1)

Discussion

Several studies of P. notoginseng transcriptome have already been carried out. Luo et al. analyzed the transcriptome of 4-year-old P. notoginseng roots by 454 GS FLX Titanium platform and presented a large-scale EST dataset (Luo et al. 2011). The transcriptome differences among the leaves, roots and flowers of 3-year-old P. notoginseng were analyzed using the Illumina HiSeq™ 2000 platform (Liu et al. 2015). JA treatment was found to significantly enhance the expression levels of notoginsenoside biosynthesis key genes in P. notoginseng and increase the biosynthesis of notoginsenosides in P. notoginseng (Niu et al. 2014). However, until now, there have been no related transcriptome analyses in P. notoginseng following JAs treatment.

Here, the transcriptomes of P. notoginseng roots were analyzed after MeJA treatment. After MeJA treatment, the differentially expressed genes between Root-MJ-0 and Root-MJ-6 identified a total of 21,947 DEGs, which had the most DEGs in metabolic pathways. Among those DEGs, 49.3% of DEGs showed upregulated expression levels, whereas the other 50.7% of DEGs showed downregulated expression levels. AP2/ERF transcription factors have been reported to play diverse functions in controlling pathways such as secondary metabolism, signal transduction, and disease resistance in plants (Van der Fits and Memelink 2000). Therefore, these significant differently AP2/ERF transcription factors may regulate the notoginsenosides metabolic pathways.

Expression profiling analysis is an effective method to screen key transcription factors in the biosynthesis of metabolites. For example, AaORA, a positive AP2/ERF transcription regulator of artemisinin in A. annua, was screened by the method of expression profiling analysis (Lu et al. 2013a, b). Based on transcriptome data in P. notoginseng roots after MeJA treatment, the expression levels of 166 AP2/ERF transcription factors were analyzed. Sixteen AP2/ERF transcription factors, which were significantly induced by MeJA treatment, were chosen for further analysis. Then, RT-qPCR was used to detect the expression levels of DS, SE, and PnERFs in the leaf, stem, root and MeJA-induced roots. Besides, genes co-expression network analysis between 16 PnERFs, DS and SE was also conducted to confirm the result. Two AP2/ERF transcription factors, PnERF2 and PnERF3, which showed similar expression patterns, have significant correlation with those notoginsenoside biosynthesis key genes DS and SE in P. notoginseng.

Phylogenetic analysis showed that PnERF2 has a close evolutionary relationship with AtERF3, AtERF7, and TcERF12. As AtERF3 and AtERF7 play important roles in abscisic acid (ABA) and drought stress responses in A. thaliana (Song et al. 2005; Fujimoto et al. 2000), PnERF2 may have similar functions in abiotic stress responses in P. notoginseng. PnERF3 has a close evolutionary relationship with AtDREB1, GhERF38, TcAP2, AtWND1, GhDBP2, ORCA1 and TcDREB. In Gossypium hirsutum L, GhERF38 and GhDBP2 as regulators that are involved in response to salt/drought stress and ABA signaling during plant development (Huang et al. 2008; Ma et al. 2017). In A. thaliana, AtDREB1 and AtWND1 are essential integrators of the JAs and ethylene signal transduction pathways. PnERF3 might have key function in plant hormone signal transduction in P. notoginseng.

Several similar jasmonate-responsive AP2/ERF transcriptional factors in different plants have important functions to regulate terpenoid biosynthesis (Theologis et al. 2000; Mayer et al. 1999). Overexpressing ORCA3 resulted in enhanced expression levels of several metabolite biosynthetic genes and significantly increased accumulation of terpenoid indole alkaloids in C. roseus (Van der Fits and Memelink 2000). Jasmonate-responsive AP2/ERF transcriptional factors AaORA, AaERF1 and AaERF2 in A. annua also showed positive regulatory function in artemisinin biosynthesis (Yu et al. 2012; Lu et al. 2013a, b). AtERF5 and AtERF6 are positive regulators of JA-mediated defense in A. thaliana (Moffat et al. 2012). In light of all the aforementioned results, PnERF3, which has similar expression pattern with DS and SE and shows close evolutionary relationships to AtDREB1A, GhERF38 and TcAP2, should be an important target in the notoginsenoside biosynthesis and disease resistance related gene of P. notoginseng.

In summary, using a high-throughput transcriptome sequencing platform, comprehensive analysis of untreated and MeJA-treated P. notoginseng roots was performed. Ultimately, 166 AP2/ERF transcription factors were identified. 16 AP2/ERF transcription factors, which were differentially expressed unigenes, were filtered in response to MeJA treatment. Then, those 16 AP2/ERF transcription factors were further analyzed by RT-qPCR. The results indicated that two AP2/ERF transcription factors, PnERF2 and PnERF3, have similar expression patterns with notoginsenoside biosynthesis key genes DS and SE. In addition, phylogenetic tree were performed to analysis relationships between PnERFs candidates and AP2/ERF transcription factors in other species. This study contributes to the sequencing data of P. notoginseng after MeJA treatment and will facilitate further investigations of the molecular biological mechanisms of this species. In addition, it provides an important target of disease resistance and notoginsenoside biosynthesis in P. notoginseng.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Beijing Genomics Institute at Shenzhen for its assistance in original data processing and related bioinformatics analysis. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFC1711000), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 81973414), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2632019ZD15), "Double First-Class" University project (CPU2018GY09), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant no. BK20140663 and BK20191319) and Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX19_0650).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: PL and XL; investigation: TL, JD and XZ; project administration PZ; writing—original draft preparation, TL; writing—review and editing, XL.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Tingwen Lin, Email: alintingwen@163.com.

Jinfa Du, Email: djf371526@163.com.

Xiaoyan Zheng, Email: iszxy@foxmail.com.

Ping Zhou, Email: apple0366@163.com.

Ping Li, Email: liping2004@126.com.

Xu Lu, Email: luxu666@163.com.

References

- Audic S, Claverie JM. The significance of digital gene expression profiles. Genome Res. 1997;7:986–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A, Gotz S, Garcia-Gomez JM, Terol J, Talon M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng B, Huang Z, Ge F, Liu D, Lu R, Chen C. An AP2/ERF family transcription factor PnERF1 raised the biosynthesis of saponins in Panax notoginseng. J Plant Growth Regul. 2017;36(3):691–701. [Google Scholar]

- Du CF, Hu KN, Xian SS, Liu CQ, Fan JC, Tu JX, Fu T. Dynamic transcriptome analysis reveals AP2/ERF transcription factors responsible for cold stress in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) Mol Genet Genom. 2016;291:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-1161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto SY, Ohta M, Usui A, Shinshi H, Ohme-Takagi M. Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive element binding factors act as transcriptional activators or repressors of GCC box-mediated gene expression. Plant Cell. 2000;12:393–404. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu XC, Chen JF, Xiao Y, et al. Overexpression of allene oxide cyclase promoted tanshinone phenolic acid production in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Plant Cell Rep. 2012;31:2247–2259. doi: 10.1007/s00299-012-1334-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z, Zhang H, Gao S, Lercher MJ, Chen WH, Hu S. Evolview v2: an online visualization and management tool for customized and annotated phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W236–W241. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Jin L, Liu JY. Identification and characterization of the novel gene GhDBP2 encoding a DRE-binding protein from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) J Plant Physiol. 2008;165(2):214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovski E, Jenkins A, Dias AG, et al. Effects of Korean red ginseng (Panax ginseng CA Mayer) and its isolated ginsenosides and polysaccharides on arterial stiffness in healthy individuals. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:469–472. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmazyn M, Gan XT. Treatment of the cardiac hypertrophic response and heart failure with ginseng, ginsenosides, and ginseng-related products. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2017;95(10):1170–1176. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2017-0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Zhang DB, Yang DC. Biosynthesis and biotechnological production of ginsenosides. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33:717–735. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung KW, Wong AST. Pharmacology of ginsenosides: a literature review. Chin Med. 2010;5:20. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu MH, Yang BR, Cheung WF, et al. Transcriptome analysis of leaves, roots and flowers of Panax notoginseng identifies genes involved in ginsenoside and alkaloid biosynthesis. BMC Genom. 2015;16:265. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1477-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Pan J, Yang Y, Cui X, Qu Y. Production of minor ginenosides from Panax notoginseng by microwave processing method and evaluation of their blood-enriching and hemostatic activity. Molecules. 2018;23(6):1243. doi: 10.3390/molecules23061243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the –ΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Jiang WM, Zhang L, et al. AaERF1 positively regulates the resistance to Botrytis cinerea in Artemisia annua. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e57657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Zhang L, Zhang F, et al. AaORA, a trichome-specific AP2/ERF transcription factor of Artemisia annua, is a positive regulator in the artemisinin biosynthetic pathway and in disease resistance to Botrytis cinerea. New Phytol. 2013;198:1191–1202. doi: 10.1111/nph.12207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Sun C, Sun Y, et al. Analysis of the transcriptome of Panax notoginseng root uncovers putative triterpene saponin-biosynthetic genes and genetic markers. BMC Genom. 2011;12(Suppl 5):S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-S5-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Hu L, Fan J, Amombo E, Khaldun ABM, Zheng Y, Chen L. Cotton GhERF38 gene is involved in plant response to salt/drought and ABA. Ecotoxicology. 2017;26(6):841–854. doi: 10.1007/s10646-017-1815-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer K, Schüller C, Wambutt R, et al. Sequence and analysis of chromosome 4 of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 1999;402(6763):769. doi: 10.1038/47134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat CS, Ingle RA, Wathugala DL, Saunders NJ, Knight H, Knight MR. ERF5 and ERF6 play redundant roles as positive regulators of JA/Et-mediated defense against Botrytis cinerea in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e35995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:182–185. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag SA, Qin JJ, Wang W, Wang MH, Wang H, Zhang R. Ginsenosides as anticancer agents: in vitro and in vivo activities, structure–activity relationships, and molecular mechanisms of action. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:25. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y, Luo H, Sun C, Yang TJ, Dong LL, Huang LF, Chen S. Expression profiling of the triterpene saponin biosynthesis genes FPS, SS, SE, and DS in the medicinal plant Panax notoginseng. Gene. 2014;533:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X, Fang H, Yu X, et al. Transcriptome analysis of JA signal transduction, transcription factors, and monoterpene biosynthesis pathway in response to methyl jasmonate elicitation in Mentha canadensis L. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(8):2364. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao YJ, Shang JH, Wang D, Zhu H, Yang CR, Zhang YJ. Research of Panax spp. in Kunming Institute of Botany, CAS. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2018;8(4):245–263. doi: 10.1007/s13659-018-0176-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song CP, Agarwal M, Ohta M, Guo Y, Halfter U, Wang PC, Zhu JK. Role of an Arabidopsis AP2/EREBP-type transcriptional repressor in abscisic acid and drought stress responses. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2384–2396. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.033043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theologis A, Ecker JR, Palm CJ, et al. Sequence and analysis of chromosome 1 of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2000;408(6814):816. doi: 10.1038/35048500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Fits L, Memelink J. ORCA3, a jasmonate-responsive transcriptional regulator of plant primary and secondary metabolism. Science. 2000;289:295–297. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CZ, McEntee E, Wicks S, Wu JA, Yuan CS. Phytochemical and analytical studies of Panax notoginseng (Burk.) FH Chen. J Nat Med. 2006;60:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, Fang L, Zheng H, et al. WEGO: a web tool for plotting GO annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:293–297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu ZX, Li JX, Yang CQ, Hu WL, Wang LJ, Chen XY. The jasmonate-responsive AP2/ERF transcription factors AaERF1 and AaERF2 positively regulate artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua L. Mol Plant. 2012;5:353–365. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZL, Wang WQ, Wang Y, Yang JZ, Cui XM. Influence of Panax notoginseng continuous cropping on seed germination and seedling growth of the plant. Chin J Ecol. 2010;29:1493–1497. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.