Abstract

Active and inactive chromatin are spatially separated in the nucleus. In Hi-C data, this is reflected by the formation of compartments, whose interactions form a characteristic checkerboard pattern in chromatin interaction maps. Only recently have the mechanisms that drive this separation come into view. We discuss new insights into these mechanisms and possible functions in genome regulation. Compartmentalization can be understood as a microphase segregated block co-polymer. Microphase separation can be facilitated by chromatin factors that associate with compartment domains, and that can engage in liquid-liquid phase separation to form subnuclear bodies, as well as by acting as bridging factors between polymer sections. We then discuss how a spatially segregated state of the genome can contribute to gene regulation, and highlight experimental challenges for testing these structure function relationships.

Keywords: Compartment, Euchromatin, Heterochromatin, HP1, microphase separation

Chromatin compartmentalization is an organizing principle of the nucleus

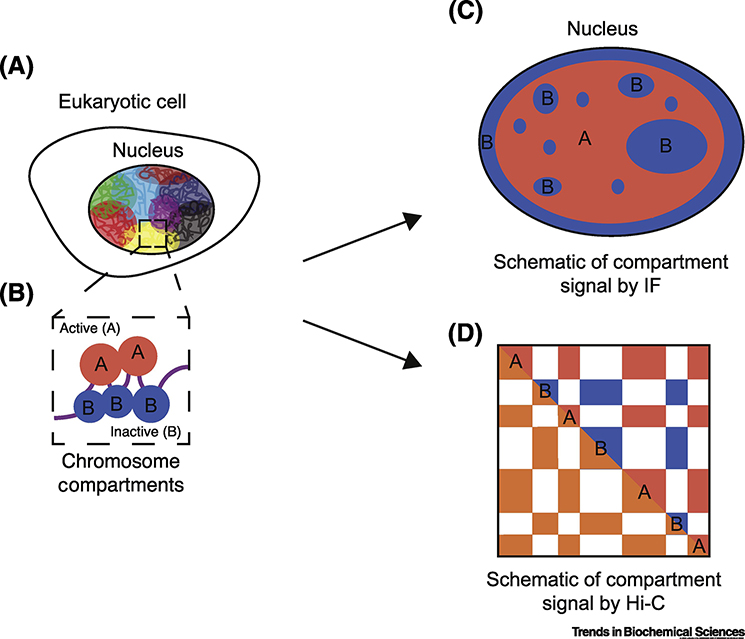

Within each eukaryotic nucleus, DNA is intricately folded. Chromosome organization is important both for resolving the physical problem of how to fit very long DNA molecules into a nucleus with a much smaller diameter, and to ensure that the DNA within the nucleus is correctly regulated [1–3]. There are two major types of chromatin which are spatially separated within the nucleus, euchromatin (see Glossary) and heterochromatin [1–3] (Figure 1). The different types of chromatin were first described by differential DNA staining in early microscopy experiments, and have since been extensively studied [2, 4]. Euchromatin is characterized by the presence of active genes, wider spacing between nucleosomes, higher accessibility, and histone marks such as H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H4K8ac, and H4K16ac, as well as histone variants H2A.Z and H3.3 [5, 6]. In contrast, heterochromatin is transcriptionally inactive, less accessible, and is decorated with H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 histone marks [5, 6]. Microscopy studies have also revealed that heterochromatin and euchromatin are spatially segregated, with heterochromatin mainly localized at the nuclear periphery and the region surrounding the nucleoli, while euchromatin is positioned in the interior of the nucleus [2] (Figure 1C).

Figure 1:

Active and inactive genomic regions form microphase separated compartments in the eukaryotic nucleus.

A. Schematic of a eukaryotic cell nucleus showing different chromosomes in different colors to illustrate chromosome territories.

B. Each chromosome is made up of both euchromatin or active (A, red) and heterochromatin or inactive (B, blue) chromatin which spatially cluster to form separate compartments within the nucleus.

C. Schematic of subnuclear localization of A and B compartments. B compartments (blue) are spatially localized to the nuclear periphery and surrounding the nucleoli, while A compartments (red) are more interior.

D. A and B compartments are visible in Hi-C matrices by a characteristic ‘checkerboard’ pattern (bottom left triangle), which, when subject to eigenvector decomposition, consist of alternating A and B compartments (top right triangle).

Genome-wide analysis of epigenetic marks using a wide range of methods including ChIP-Seq, CUT&RUN, ATAC-seq, DNAse-seq, and others have revealed that regions of euchromatin and heterochromatin alternate along the length of chromosomes [7–10]. Analysis of chromosome conformation using methods such as Hi-C, SPRITE, TSA-Seq, HiChIP, and GAM show that these domains are spatially segregated [11–16]. In a Hi-C pair-wise interaction heatmap, active and inactive regions of the genome exhibit a ‘plaid’ or ‘checkerboard’ pattern (Figure 1D), showing that not only do individual active and inactive regions remain spatially separated, but, in addition, each type of chromatin interacts with distal regions of the same type [11]. Eigenvector deconvolution analysis of Hi-C data can be used to identify regions that correspond to each type of chromatin, which are termed the ‘A’ (active) and ‘B’ (inactive) compartments, and which correspond to euchromatin and heterochromatin, respectively [11]. In addition, these nuclear compartments are correlated with replication timing, with A compartments replicating earlier than B compartments [17]. Further studies have shown that within A and B compartments, there are also sub-compartments corresponding to specific combinations of epigenetic marks [18].

While the presence of active and inactive nuclear compartments is now well established, the mechanisms that drive this organization and the functional relevance of spatial clustering of chromatin domains, e.g. for gene regulation, have been open questions in the field, and are currently the focus of intense study. In the past 2.5 years, the field has shifted dramatically due to publications showing that phase separation may be the mechanism that separates heterochromatin from euchromatin, and follow-up studies have shown that this mechanism may be more broadly applicable to other types of chromatin [19–21]. However, in the past year, new publications and a recent review on the topic argue that phase separation may not be the only explanation for clustering of genomic loci in vivo, and that other mechanisms may also be important [22, 23]. It is also clear that while compartments are correlated with gene regulation, the specific function of long-range compartment interactions is still not completely understood. This review will cover these recent advances on the topics of the mechanisms of chromosome compartmentalization, what is known about the function of long-range compartment clustering and how this may be tested in future studies, and the interplay between compartments and other levels of chromatin organization.

Compartments are proposed to be formed by microphase separation

The biophysical processes establishing and maintaining the long-range A to A and B to B interactions that define the active and inactive nuclear compartments are starting to be explored in molecular detail [4, 19, 20, 24–27]. Recent observations and analyses strongly suggest that one process contributing to compartmentalization is phase separation. The physical principles by which long polymers that are composed of alternating blocks of monomers of different type (such as A and Bcompartments along chromosomes) can phase separate are well known [28–30]. This type of polymer is termed a block copolymer, and can fold so that blocks of each type cluster together while displaying few interactions with blocks of the other type (Figure 2A). Importantly, such copolymers display microphase separation, and not macrophase separation. This means that the spatial clusters are relatively small and that the two types of blocks do not entirely separate in just two large domains. This is due to the covalent linkages between blocks of different types that prevent their complete macroscopic segregation. The ability to microphase separate is dependent on the length of the blocks (size of chromatin domains) and the strength of the preference of domains to interact with other domains of the same type [28–30].

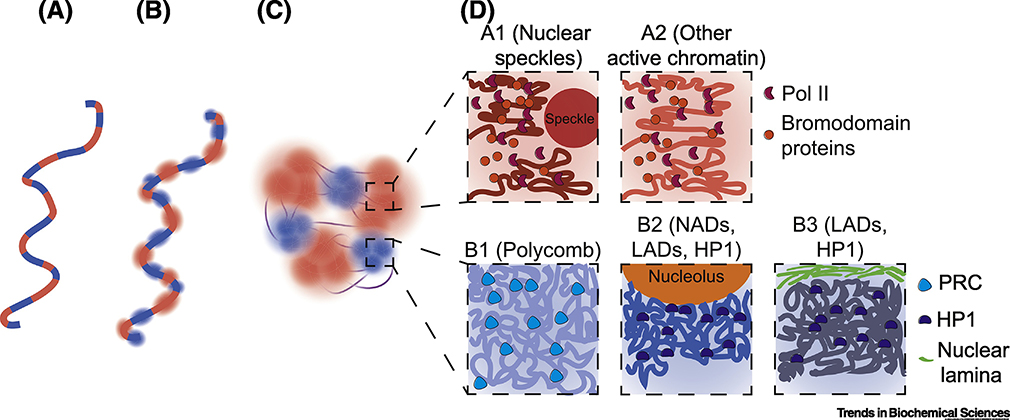

Figure 2:

Mechanisms of compartmentalization.

A. The chromatin fiber is a block co-polymer consisting of alternating active (A, red) and inactive (B, blue) blocks (domains).

B. Each type of domain recruits separate multivalent binding factors, as depicted by fuzzy interactions.

C. Chromatin domains with similar marks and binding proteins localize together; this is proposed to be through a microphase separation mechanism. The binding factors may act as bridging factors mediating PPPS or participate in LLPS, depending on the context.

D. Euchromatic regions consist of the A1 (dark red) and A2 (lighter red) sub-compartments [18], have low chromatin density, and are bound by Pol II (red major sectors) and binding factors such as Bromodomain containing proteins (orange circles). A1 domains differ from A2 domains in that A1 domains are in close proximity to Nuclear Speckles (large red circle), while A2 is active chromatin more distant from Nuclear Speckles. Heterochromatin is split into the B1 (light blue), B2 (medium blue), and B3 (dark blue) sub-compartments, and has a higher DNA density than the A compartment. The B1 sub-compartment is bound by the Polycomb complex (light blue rounded triangle) while the B2 and B3 sub-compartments contain HP1 (dark blue bean shape). B2 is often near the nucleoli (orange semicircle), consisting of nucleolar associating domains (NADs), while B3 is frequently close to the nuclear lamina (green lines), and consists of lamina associating domains (LADs).

Microphase separation of DNA in the nucleus has been proposed to occur through two related mechanisms that differ in the properties of the factors that mediate interactions between chromatin fibers: polymer-polymer phase separation (PPPS) and liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) (reviewed in [21]). Briefly, PPPS occurs when bridging factors bind to a polymer, i.e. the chromatin fiber, such that each bridging factor crosslinks two polymer blocks in the same state, i.e. A to A, but does not necessarily interact with other bridging factors [21, 31]. In LLPS, multivalent interactions between factors such as proteins or nucleic acids form macro-molecular structures with liquid-like properties [21]. LLPS can occur in any part of the cell, and does not necessarily require the involvement of a polymer; however, in the context of chromosomes, the interactions can occur between the DNA polymer and binding factors, as well as between the binding factors themselves, mediating long-range genomic interactions [21]. A key distinction between these models is that in LLPS, the binding factors can form droplets even in the absence of the polymer, which is not the case for bridging factors involved in PPPS [21]. However, in the context of the chromatin polymer, it can be difficult to distinguish between these two mechanisms; some binding factors may act as either PPPS bridging factors or LLPS mediating factors depending on circumstances, such as local concentration or post-translational modifications of the binding factor. In addition, the chromatin polymer itself may contribute to long-range interactions due to different types of histone modifications that can self-associate [31, 32]. A third mechanism that could lead to microphase separation in the nucleus is liquid-solid phase separation (LSPS), where, in the context of a chromosome, the factors decorating one chromatin state would cause it to behave like a liquid, while those bound to the other would have the properties of a solid, thereby causing spatial separation [33, 34]. In vivo, it is likely that some combination of all three of these mechanisms is occurring, leading to the compartmentalized cell nucleus.

Recent chromosome compartment studies have focused mainly on LLPS as a mechanism of chromatin compartment formation, due to the discovery that some chromatin binding proteins can participate in LLPS or formation of condensates in vitro [19, 20, 26, 27]. This presents an attractive model for segregation of active and inactive chromatin within the nucleus, as self-association of these proteins and local concentration gradients may be able to drive separation of A and B compartments (Figure 2B–C). Nucleolar assembly is also proposed to occur through LLPS, and may represent a possible third compartment of highly repetitive DNA that forms a distinct nuclear body from the A and B compartments, but is difficult to study by high-throughput sequencing due to the repetitive nature of the rDNA sequence [35, 36].

LLPS occurs when both phases have liquid-like properties, such as high mobility of the individual molecules and can occur through low affinity, high valency interactions between disordered regions of proteins, such as a domain of a chromatin binding factor [19, 20, 26, 27]. When the local concentration of the protein with an intrinsically disordered region (IDR) is above a certain threshold, such as when bound to a region of chromatin with a particular epigenetic mark, this can lead to spontaneous aggregation of both the IDR and the binding partners [19, 20, 26, 27]. The resulting condensates can have different physical properties, depending on the components. It should be noted, however, that while there is increasing evidence for LLPS in chromosome compartmentalization, concerns have also been raised that other mechanisms may explain some of the observations attributed to LLPS, and that it will be important to establish robust tests for LLPS in vivo to rule out alternative mechanisms [22, 23]. For instance, it is possible that factors that by themselves can form liquid condensates, actually mediate chromatin compartmentalization through acting as bridging factors (see below).

Evidence for LLPS in the A and B compartments

LLPS in the B compartment is proposed to happen in two different ways. In one part of this model, LLPS on H3K9me3 marked chromatin is mediated through the heterochromatin protein HP1 (Figure 2D). The a/alpha isoform of HP1 has been shown to form condensates alone and with polynucleosomes in vitro, and in Drosophila melanogaster embryos in vivo [19, 20]. It has also been shown that binding of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe HP1 protein Swi6 deforms the nucleosome core octamer in vitro, resulting in increased solvent accessibility, but also increased nucleosome concentration within the condensates [37]. Phase separated compartments formed with a different HP1 isoform, HP1 beta, its binding partner SUV39H1, and H3K9me3 modified nucleosomes exclude active chromatin proteins in vitro [38]. In addition, ectopic targeting of HP1 alpha to the lac operator results in an increased density and condensation of the targeted chromatin [39]. However, while HP1 alpha is capable of forming liquid droplets, it is possible that in vivo HP1 alpha can also act directly as a bridging factor to establish and/or maintain heterochromatic microphases. Similarly, on H3K27me3 marked chromatin, LLPS is proposed to be mediated by the Polycomb complex, which can form droplets in vitro [40] (Figure 2D). Mutations in CBX2, a subunit of the Polycomb complex, can disrupt Polycomb puncta in cells [40–42]. Recently, short stretches of chromatin alone have also been shown to be able to form droplets via a nucleosome intrinsic mechanism using an in vitro system of polynucleosome arrays. It was shown that formation of these phase separated bodies in vitro required unacetylated histone tails [32]. In these experiments, droplet formation requires the linker histone H1 when linkers between nucleosomes are long [32].

While LLPS has been more extensively studied in the context of heterochromatin, it is important to recognize that the A compartment is not just a region that is excluded from the heterochromatic microphase. In fact, A compartments likely form their own euchromatic microphase separated bodies mediated by unstructured regions on certain transcriptional regulators such as BRD4, TAF15, and FUS, as well as RNAs and RNA binding proteins [27, 32, 43]. For example, in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), mutations in FUS can lead to aggregation, which may represent a LSPS transition [34]. On in vitro polynucleosome templates, acetylation disrupts the chromatin intrinsic LLPS, but microphase separation can be rescued on acetylated nucleosomes with the addition of multibromodomain containing proteins which can bind to the acetylated histone tails [32]. Interestingly, when added to the same reaction, both the unmodified and acetylated chromatin with bromodomain proteins formed droplets, but each droplet only contained one of the types of chromatin and did not mix with the other type [32]. RNA Polymerase II may also contribute to phase separation in active regions such as super-enhancers via the intrinsically disordered Pol II C-terminal domain (CTD) [44]. The phosphorylation state of the CTD determines the type of condensate, with hypo-phosphorylated Pol II CTD included in Mediator containing condensates that function in transcription initiation and hyper-phosphorylated Pol II CTD interacting instead with splicing factors in separate condensates [44, 45].

Nuclear speckles are regions of the nucleus characterized by the presence of splicing factors and other mRNA processing proteins, that tend to form a cluster of active genes [46]. Depletion of the nuclear speckle structural protein Srrm2 resulted in decreased A compartment strength and increased B compartment strength by Hi-C [47] (Figure 2D). Artificial LLPS droplets made using the CasDrop system with transcriptional regulators TAF15 and FUS exclude heterochromatin and HP1 alpha, and have lower histone density than surrounding chromatin regions [27]. These measurements of chromatin density at nuclear regions impacted by different types of LLPS are consistent with measurements of chromatin density and compaction within A and B compartments by super-resolution microscopy [48–50]. Overall, the trend is that B compartments or HP1 alpha LLPS droplets have increased chromatin density compared to A compartments or transcription factor mediated LLPS droplets [39, 48–50] (Figure 2D).

Sub-compartments suggest multiple types of microphase separation

Recent work using high-resolution Hi-C datasets, as well as liquid-chromatin Hi-C (LC-Hi-C), has shown that there are multiple sub-compartments within both active and inactive chromatin [18, 51]. The general principle appears to be that chromatin with similar types of histone modifications and chromatin binding proteins tends to self-interact, but that within heterochromatin or euchromatin, there are distinct types of each kind of chromatin that are distinguishable by the stability of the interactions and by long-range clustering [18, 51]. These sub-compartments are proposed to correlate with nuclear regions observed by microscopy such as nuclear speckles/transcription factories, lamin associating domains (LADs), or nucleolus associating domains (NADs) [51]. An argument can be made that the 6 sub-compartments identified by Hi-C or the 9–25 chromatin states identified by ChromHMM or similar tools may actually correspond to loci associating with distinct demixed liquid or solid phases within the nucleus [18, 33, 52–56] (Figure 2D). LLPS has been discussed above, but LSPS is also implicated in processes such as nucleolar stress response aggresome formation [33]. In addition, some types of sub-compartments may occur due to PPPS rather than LLPS if the binding factors do not form droplets on their own [31]. These phase separated bodies and the chromatin associated with them display different physical properties such as the dynamics of factor exchange and the stability of chromatin interactions. The biochemical composition of these phase separated bodies is now being explored, but which factors are key for driving the separation in each type of chromatin is in most cases not known [53, 54].

Computational models of chromosome folding

Computational polymer models have been useful for understanding the forces determining compartmentalization, and provide a theoretical framework to explore mechanisms and properties of spatial segregation of domains on long polymers such as chromosomes [11, 21, 57–64]. It is important to note that the models discussed here model physical microphase separation of a block copolymer regardless of the precise molecular mechanism, which in vivo could be occurring by multiple mechanisms, such as bridging factors and PPPS, condensate formation and LLPS or LSPS, or intrinsic attractive forces between specific types of chromatin due to specific histone marks or variants [32]. Modeling chromosomes as block copolymers that microphase separate through interactions between blocks of the same type recapitulates the characteristic checkerboard pattern of long-range interactions observed in Hi-C maps. [60, 65]. Further, by comparing coarse grained polymer models of microphase separation to experimental results, the relative strengths of the attractive forces between different compartments can be estimated.

A recent study used comparisons between a polymer model and in vivo experiments using both immunofluorescence and Hi-C analysis in mouse rod cells that display an inverted nucleus architecture [66]. In these cells, all heterochromatin is located at the center of the nucleus, unlike in conventional nuclei where heterochromatin lines the periphery and the nucleolus. In both inverted and conventional nuclei, Hi-C shows similar checkerboard patterns, indicating spatial separation of active and inactive chromatin. Modeling shows that an inverted nucleus organization can only be formed when interactions between centromeric chromatin are the strongest, while interactions between inactive loci along chromosome arms are somewhat weaker, and interactions between active chromatin are very weak. In order for a conventional nucleus to position heterochromatin at the periphery, relatively stable tethers between heterochromatin and the nuclear lamina had to be included in the model. These models start to explore quantitatively the relative forces mediating subnuclear compartment formation, which, in the future, can be compared to forces that can be exerted through the different microphase separation mechanisms [66]. In addition, the models are also useful for investigating chromatin positioning with respect to other nuclear structures such as the lamina [66].

What is the functional relevance of chromosome compartmentalization?

One important question that has been difficult to address is whether the spatial segregation of euchromatin and heterochromatin is important for nuclear function. To test whether compartmentalization per se contributes to silencing or activating genes, one would need to disrupt long-range clustering of loci while maintaining their histone modifications and local chromatin structure. And vice versa, such functional studies would require perturbation of local chromatin modifications while maintaining compartmentalized clustering to determine if gene activity is changed. Such experiments have proven to be very difficult given that local chromatin features appear to be directly involved in compartmentalization. Further, an additional reason that it has been difficult to test the importance of higher-order structure on nuclear function is that, in many cases, there are feedback mechanisms between the histone modifications and their binding proteins, so perturbing the binding protein can then affect the level of the histone modification itself. For example, in the case of HP1 alpha and H3K9me3, HP1 alpha binding recruits histone methyl transferases, leading to further H3K9 methylation [39]. However, this also points to the possible importance of the formation of segregated microphases and higher-order chromatin structure in spreading or maintaining chromatin marks as a positive feedback mechanism could then lead to enhanced repression or activation of the targeted regions if higher levels of the binding protein was recruited to a cluster of A or B regions within the nucleus.

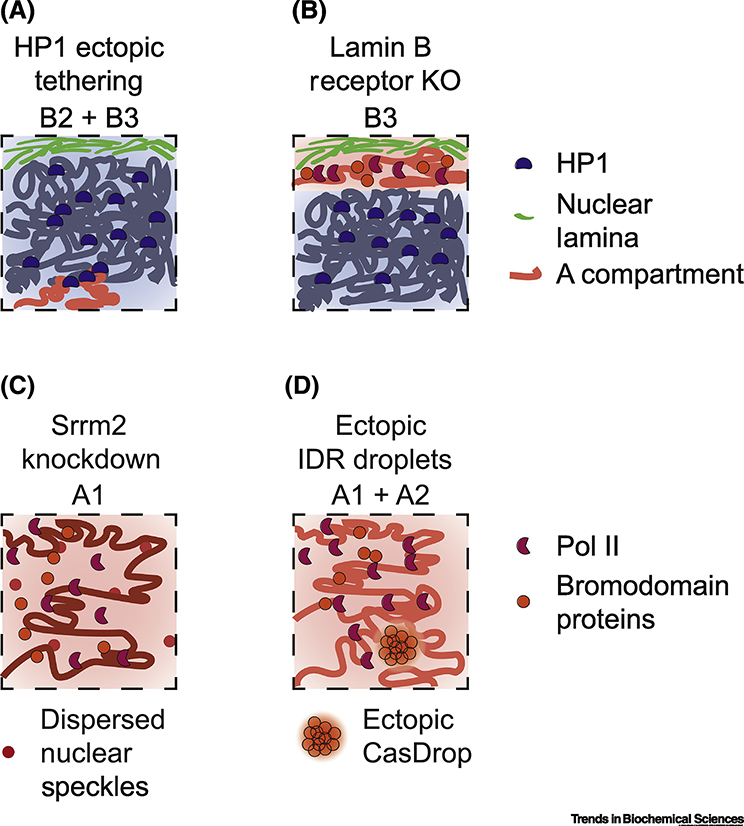

Despite these intricate interrelationships between local chromatin state and compartmentalization, some recent perturbation studies have started to shed some light on the role of factors on chromosome compartmentalization. Focusing first on the heterochromatic B compartment, it has been shown that tethering of HP1a to ectopic sites in Drosophila using the LacI system leads to transcriptional silencing of most sites, except active promoters, and the establishment of physical connections between the ectopic HP1a site and other HP1a bound sites [67] (Figure 3A). In addition, HP1a RNA interference (RNAi) disrupts localization of HP4, a different heterochromatin protein [20]. However, it is not yet known whether large scale changes in the chromatin interactions that form A and B compartments will also occur in the context of HP1a tethering or depletion. In budding yeast, which lack H3K9 trimethylation and the HP1 protein, the Sir complex is the main heterochromatin silencing system. Using chromosome conformation capture on genetic mutants of the Sir complex, it was found that silencing of specific loci in this system can occur even without long-range clustering, although stability of the silent state is reduced in this genetic background [68].

Figure 3:

Experimental perturbations to compartmentalization to elucidate function

A. Tethering of HP1 (dark blue bean) to an A compartment (light red line) using LacO/LacI results in gene silencing and new interactions forming between the ectopic HP1 site and heterochromatic regions (dark blue lines), this forms an ectopic B2 or B3 sub-compartment [67].

B. Knockout of the Lamin B receptor in mouse thymocytes results in loss of heterochromatin tethering to the nuclear periphery; however, compartmentalization per se is preserved [66]. The B3 sub-compartment is disrupted in its nuclear localization, but not in its long-range interactions. By microscopy, the A compartment (red) is now observed to be closest to the nuclear periphery, while the B compartment (blue) is within the nuclear interior.

C. Knockdown of Srrm2, a structural component of nuclear speckles (NS), results in loss of NS foci (see Figure 2D), and dispersion of the NS components (small dark red circles) throughout the nucleus. A compartment strength is decreased, while B compartment strength is increased [47]. This is specifically affecting the A1 subcompartment that is usually close to NS foci.

D. Ectopic induction of phase separated droplets using Intrinsically Disordered Region (IDR) containing proteins related to active transcription such as TAF15, FUS, or BRD4 using the CasDrop system results in droplets (fuzzy cluster of orange circles) that exclude heterochromatin, form in regions of the nucleus with low chromatin density, and can function to pull two distal active regions together by fusion of separate CasDrops, forming an ectopic A1 or A2 compartment [27].

Another feature of the B compartment is localization to the nuclear periphery by association with the nuclear lamina, which serve as nuclear envelope anchors for heterochromatin [69]. There is a large body of literature on the effects of perturbing interactions between the nuclear lamina and chromatin; however, recent results suggest that while nuclear lamins are important for proper location of heterochromatin by tethering it to the nuclear periphery, this peripheral localization is not actually required for formation of microphase separated heterochromatin [66, 70, 71]. Indeed, multiple studies have shown that while lamin depletions can lead to local changes in gene expression, these changes do not always correspond to large scale compartment changes. One of these studies tested the importance of Lamin A/C nuclear envelope anchors to B compartment strength using a model of cardiac laminopathy, where Lamin A/C was depleted in human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) that were then differentiated into cardiomyocytes [70]. Some changes in compartmentalization were observed by Hi-C in the differentiated cells, however, the majority of gene expression changes observed in the Lamin A/C depleted cells were not correlated with changes in compartments by Hi-C [70]. In addition, Hi-C and microscopy experiments in combination with equilibrium modeling in conventional (B compartment more peripheral) and inverted (B compartment more central) nuclei, derived from cells with or without Lamin B receptor respectively showed that chromosomes can compartmentalize to similar extents as measured by Hi-C with or without nuclear envelope tethering of B compartments [66] (Figure 3B). This result supports the model that compartment formation is an intrinsic property of chromatin that does not rely on tethering to the nuclear envelope [66]. Tethering of B compartments to the Lamina leads to specific subnuclear localization of these domains, but is not required for their clustering per se.

A separate study which used live-cell microscopy and modeled chromatin interactions using previously published single-cell Hi-C data showed that as cells exit mitosis, B domains that will become LADs self-associate before nuclear lamina assembly, and then move as a group to the nuclear periphery [71, 72]. In contrast, in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) fibroblast cell lines, large changes in compartmentalization and H3K27me3 are observed in late passages, near premature cellular senescence in these cells [73]. Interestingly, changes in H3K27me3 levels and Lamin A/C association preceded changes in compartmentalization of the chromosomes in this experimental system [73]. Overall, these studies suggest that while tethering of heterochromatin to the nuclear periphery is required for setting up the spatial organization of a conventional nucleus, other factors are usually sufficient for microphase separation of active and inactive chromatin. However, there may be circumstances such as cell senescence which require Lamin association to maintain compartment identity, and in these cases loss of peripheral localization of heterochromatin can lead to large scale changes in compartmentalization.

Much less is known about the role of A compartment clustering. Nuclear bodies such as speckles appear to be related to compartmentalization, as deletion of Srrm2 in mouse hepatocytes, which disrupts nuclear speckles, reduces the strength of A-A clustering [47] (Figure 3C). In Drosophila, inhibition of transcription elongation has been shown to reduce A-A interactions, but seems to have little effect on shorter range interactions along the diagonal of a Hi-C map during development [74, 75]. However, it is difficult to determine if the changes in long-range interactions are important for function, as transcription is already inhibited in these experiments. An interesting study using the CasDrop system showed that transcriptional regulators that contain IDRs can form droplets in vivo, and that these droplets exclude HP1 and heterochromatin, and are surrounded by active chromatin [27] (Figure 3D). Additionally, this study showed that fusion of two droplets could bring distal active regions together, which may contribute to long-range clustering of similar compartments. However, it has not yet been shown whether this clustering causes changes in gene activity. Further studies have shown that acetylated nucleosomes can also form phase separated droplets in vitro in the presence of bromodomain containing proteins, and these droplets exclude unacetylated nucleosomes [32]. Future work building on these tools will determine if loss or ectopic localization of bromodomain containing proteins which can induce phase separation of acetylated histones also changes A compartment interactions, and how this affects transcriptional activity.

Another approach to study the mechanism and function of nuclear compartments is to analyze this phenomenon across different cellular stages, tissue types, or organisms. One example of how this can be useful is considering the case of mitotic versus interphase cells, as mitotic cells have been shown by proteomics to retain many epigenetic marks though long-range compartment interactions are not present [76, 77]. In this case, many of the protein-protein interactions required for phase separation are likely disrupted by transient cell-cycle regulated phosphorylation and other post-translational modifications that occur during mitosis, such as H3S10 phosphorylation [76]. H3S10 phosphorylation disrupts HP1 binding to H3K9me3 marked histones [78]. By identifying events that regulate compartmentalization in different cell cycle states, we may be able to use these processes to perturb compartments in other contexts to gain greater understanding of the function of long-range interactions. In addition, cells derived from different tissues have been shown to have very different compartment strengths, providing a natural set of conditions to analyze the quantitative effects of compartment formation on gene activity [46, 66].

The antagonistic relationship between compartments and TADs

Within each nucleus, compartments exist in the same space and can overlap on the same polymers with topologically associating domains (TADs), but appear to be formed by different mechanisms. The balance between compartment and TAD formation may be important for correct regulation of chromosome function [61, 79, 80]. TADs are thought to be formed by cohesin mediated loop extrusion, are highly dynamic, and while they can form nested TAD structures, they do not generally have long range interactions beyond 1 Mb [61, 79, 80]. In contrast, compartments are thought to be formed by phase separation, and it is unknown if they are dynamic or stable structures. Compartment domains can associate over very large genomic distances (100s of Mb), and also with domains located on other chromosomes [11].

Cohesin loading and unloading proteins can be manipulated to modulate the level of loop extrusion experimentally. In experiments with decreased loop length, such as cohesin subunit depletions (Rad21-AID; Nipbl KO, Scc4 KO), compartment strength is increased, and small compartments become apparent within what is a TAD in the WT background, suggesting that loop extrusion usually prevents these small compartments from being formed [81–85]. In contrast, in cell lines lacking the cohesin unloader, Wapl, loop size increases, and the strength of compartmentalization is reduced [81, 86]. One hypothesis is that loop extrusion can pull sections of chromatin into a compartment that is inconsistent with their chromatin state. In effect, when loop extrusion is sufficiently strong, each TAD becomes a unit of phase separation. When loop extrusion is then inactivated, the intrinsic compartmentalization driven only by local chromatin state emerges, consistent with formation of new small compartment domains in the Nipbl mutant [85]. Modulating compartment strength separately from changing loop extrusion will be an important next line of experimentation, to determine if compartmentalization affects TAD formation as well.

This interplay between TADs and compartments has also been modeled, and these modeling experiments suggest that the balance between the strengths of these two processes is important to allow both to occur simultaneously on the DNA polymer [61]. Examples of cell types or organisms with extremely strong compartments or TADs would be interesting to study in this context to determine the effects of imbalance in the relationship between TADs and compartments on genomic function. For instance, studies in Drosophila suggest that in this species, the genome may be organized only by compartments, and not by the loop extrusion mechanism that is thought to contribute to TAD structure in mammalian nuclei. Therefore, Drosophila will be an interesting model system for further study of compartment function [74, 75].

Concluding remarks

Chromosome compartmentalization separates active and inactive regions of the genome, and is proposed to occur via a microphase separation mechanism. Both the A and B compartments contain putative LLPS factors, and polymer models of microphase separation recapitulate Hi-C compartment data. However, it is important to note that it is not yet known whether all of the protein-protein interactions mediating compartment interactions are actually engaged in LLPS or PPPS in vivo, or if some other mechanism is occurring such as the formation of hubs of specific activity based on concentration of protein binding sites. As has been recently discussed, such hubs do not always have to form by the process of LLPS [22, 23]. This is still a topic of active debate in the field. Another interesting avenue of future work is to look beyond eukaryotic genome organization. Although compartments have generally been studied in eukaryotes, very recent work suggests that compartmentalization occurs in some Archaea as well, but whether the mechanism is similar or different from that in eukaryotes is as yet unknown [87].

Future research should also focus on the relationship between long-range compartment clustering and chromatin function (see Outstanding Questions). These are difficult questions to answer, as many of the perturbations that would be predicted to globally affect compartmentalization will also have an effect on gene expression directly, so it will be useful to identify new ways of inducing or disrupting phase separation or long-range chromatin interactions independent of gene expression or replication timing. The optical tools developed by the Brangwynne lab could provide new ways to address this question [27]. Finally, little is known about the kinetics and dynamics of establishment and maintenance of chromosome compartmentalization, e.g. during the cell cycle or development, and how compartments vary from cell to cell, and we expect these topics to be the focus of intense studies in the coming years.

Outstanding Questions.

Is clustering of distal A or B compartments important for chromatin function?

Is gene expression or DNA replication more efficiently regulated when regions of similar activity are clustered in space?

Is clustering of different types of chromatin a consequence or a cause of chromatin regulation?

What are the phase separation factors for each of the sub-compartments?

Does any mixing occur between different sub-compartments within either heterochromatin or euchromatin?

What are the dynamics of establishment of compartmentalization, e.g. during the cell cycle and differentiation?

How much cell to cell variation is there to compartmentalization, and how does this effect chromosome activity at the single cell level?

What are the mechanistic interplays between compartmentalization and other chromosome folding processes such as loop extrusion?

Highlights.

Recent studies have shown that chromosome and nuclear compartmentalization may be driven by a process of phase separation

Subnuclear positioning of compartments can be achieved by tethering to the lamina, the nucleoli, and other subnuclear bodies

Compartmentalization can be counteracted by loop extrusion

Phase separated compartments may function in transcriptional control by in- and ex-cluding specific co-factors required for gene regulation

Recently developed tools will allow researchers to interrogate the function of long-range compartment interactions and phase separated regions of the nucleus

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by R01 HG003143 to JD, and F32 CA224689 to EH. Job Dekker is an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Glossary

- Block copolymer

polymer that is composed of alternating blocks of monomers of different types

- Bridging Factor

a factor that binds to two regions of the same type in a block copolymer to form a crosslink, resulting in polymer-polymer phase separation (PPPS). In the case of chromatin, a bridging factor would be a protein or protein complex and/or RNA that binds to two genomic regions of the same compartment, but that do not necessarily bind to other bridging factors to form multivalent interactions

- CasDrop System

CRISPR-Cas9 based optogenetic technology developed by the Brangwynne lab that can induce localized condensation of liquid droplets at specific genomic loci

- Chromosome Territory

region of the nucleus that is occupied by chromatin from just one chromosome. By Hi-C, chromosomes tend to have more intra-chromosomal interactions than intra-chromosomal interactions even for loci separated by very large genomic distances, which reflects this organization that was first observed by microscopy

- Euchromatin

type of chromatin characterized by the presence of active genes, low chromatin density, and active histone marks and variants. Corresponds to the A compartment

- Heterochromatin

type of chromatin characterized by being transcriptionally silent, with a higher chromatin density, and inactive histone marks. Corresponds to the B compartment

- Intrinsically Disordered Region

region of a protein that does not have any defined secondary or tertiary structure due to the amino-acid sequence

- Macrophase

type of phase separation where the phases become completely separated into one large region per phase. Usually applied to large scale ‘macroscopic’ processes, but can also apply to microscopic processes where the phase separation leads to complete segregation of the materials

- Microphase

type of phase separation where the spatial clusters are relatively small and the two types of material do not entirely separate in just two large domains, but into many small domains for each type

- Phase Separation

separation of two substances in a mixture based on their physical properties. Eg. Oil and water

- Polymer

large macromolecule that is made up of a string of smaller repeating subunits called monomers

- Super-Enhancer

cluster of enhancers with very high levels of transcription activating factors, often regulate genes important for cell identity

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.de Wit E and de Laat W 2012. A decade of 3C technologies: insights into nuclear organization. Genes Dev 26 (1): 11–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bickmore WA and van Steensel B 2013. Genome architecture: domain organization of interphase chromosomes. Cell 152 (6): 1270–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dekker J and Mirny L 2016. The 3D Genome as Moderator of Chromosomal Communication. Cell 164 (6): 1110–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Passarge E 1979. Emil Heitz and the concept of heterochromatin: longitudinal chromosome differentiation was recognized fifty years ago. Am J Hum Genet 31 (2): 106–15 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrence M, Daujat S, and Schneider R 2016. Lateral Thinking: How Histone Modifications Regulate Gene Expression. Trends Genet 32 (1): 42–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talbert PB and Henikoff S 2017. Histone variants on the move: substrates for chromatin dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18 (2): 115–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albert I, Mavrich TN, Tomsho LP, Qi J, Zanton SJ, Schuster SC, and Pugh BF 2007. Translational and rotational settings of H2A.Z nucleosomes across the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 446 (7135): 572–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skene PJ and Henikoff S 2017. An efficient targeted nuclease strategy for high-resolution mapping of DNA binding sites. Elife 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, and Greenleaf WJ 2013. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods 10 (12): 1213–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyle AP, Davis S, Shulha HP, Meltzer P, Margulies EH, Weng Z, Furey TS, and Crawford GE 2008. High-resolution mapping and characterization of open chromatin across the genome. Cell 132 (2): 311–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lieberman-Aiden E, van Berkum NL, Williams L, Imakaev M, Ragoczy T, Telling A, Amit I, Lajoie BR, Sabo PJ, Dorschner MO, Sandstrom R, Bernstein B, Bender MA, Groudine M, Gnirke A, Stamatoyannopoulos J, Mirny LA, Lander ES, and Dekker J 2009. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 326 (5950): 289–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quinodoz SA, Ollikainen N, Tabak B, Palla A, Schmidt JM, Detmar E, Lai MM, Shishkin AA, Bhat P, Takei Y, Trinh V, Aznauryan E, Russell P, Cheng C, Jovanovic M, Chow A, Cai L, McDonel P, Garber M, and Guttman M 2018. Higher-Order Inter-chromosomal Hubs Shape 3D Genome Organization in the Nucleus. Cell 174 (3): 744–57 e24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Zhang L, Brinkman EK, Adam SA, Goldman R, van Steensel B, Ma J, and Belmont AS 2018. Mapping 3D genome organization relative to nuclear compartments using TSA-Seq as a cytological ruler. J Cell Biol 217 (11): 4025–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fullwood MJ and Ruan Y 2009. ChIP-based methods for the identification of long-range chromatin interactions. J Cell Biochem 107 (1): 30–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mumbach MR, Rubin AJ, Flynn RA, Dai C, Khavari PA, Greenleaf WJ, and Chang HY 2016. HiChIP: efficient and sensitive analysis of protein-directed genome architecture. Nat Methods 13 (11): 919–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beagrie RA, Scialdone A, Schueler M, Kraemer DC, Chotalia M, Xie SQ, Barbieri M, de Santiago I, Lavitas LM, Branco MR, Fraser J, Dostie J, Game L, Dillon N, Edwards PA, Nicodemi M, and Pombo A 2017. Complex multi-enhancer contacts captured by genome architecture mapping. Nature 543 (7646): 519–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dileep V and Gilbert DM 2018. Single-cell replication profiling to measure stochastic variation in mammalian replication timing. Nat Commun 9 (1): 427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao SS, Huntley MH, Durand NC, Stamenova EK, Bochkov ID, Robinson JT, Sanborn AL, Machol I, Omer AD, Lander ES, and Aiden EL 2014. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell 159 (7): 1665–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larson AG, Elnatan D, Keenen MM, Trnka MJ, Johnston JB, Burlingame AL, Agard DA, Redding S, and Narlikar GJ 2017. Liquid droplet formation by HP1alpha suggests a role for phase separation in heterochromatin. Nature 547 (7662): 236–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strom AR, Emelyanov AV, Mir M, Fyodorov DV, Darzacq X, and Karpen GH 2017. Phase separation drives heterochromatin domain formation. Nature 547 (7662): 241–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erdel F and Rippe K 2018. Formation of Chromatin Subcompartments by Phase Separation. Biophys J 114 (10): 2262–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McSwiggen DT, Hansen AS, Teves SS, Marie-Nelly H, Hao Y, Heckert AB, Umemoto KK, Dugast-Darzacq C, Tjian R, and Darzacq X 2019. Evidence for DNA-mediated nuclear compartmentalization distinct from phase separation. Elife 8 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McSwiggen DT, Mir M, Darzacq X, and Tjian R 2019. Evaluating phase separation in live cells: diagnosis, caveats, and functional consequences. Genes Dev [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ditlev JA, Case LB, and Rosen MK 2018. Who’s In and Who’s OutCompositional Control of Biomolecular Condensates. J Mol Biol 430 (23): 4666–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banani SF, Lee HO, Hyman AA, and Rosen MK 2017. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18 (5): 285–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin Y, Protter DS, Rosen MK, and Parker R 2015. Formation and Maturation of Phase-Separated Liquid Droplets by RNA-Binding Proteins. Mol Cell 60 (2): 208–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin Y, Chang YC, Lee DSW, Berry J, Sanders DW, Ronceray P, Wingreen NS, Haataja M, and Brangwynne CP 2018. Liquid Nuclear Condensates Mechanically Sense and Restructure the Genome. Cell 175 (6): 1481–91 e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Gennes P-G, 1979, Scaling concepts in polymer physics. (Cornell University Press, 1979). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liebler L 1980. Theory of microphase separation in block copolymers. Macromolecules 13 1602–17 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsen MW, Schick M 1994. Stable and unstable phases of a linear multiblock copolymer melt. Macromolecules 27 7157–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh PB and Newman AG 2019. On the relation of phase separation and Hi-C maps to epigenetics. bioRxiv 814566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibson BA, Doolittle LK, Schneider MWG, Jensen LE, Gamarra N, Henry L, Gerlich DW, Redding S, and Rosen MK 2019. Organization of Chromatin by Intrinsic and Regulated Phase Separation. Cell 179 (2): 470–84 e21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Latonen L 2019. Phase-to-Phase With Nucleoli - Stress Responses, Protein Aggregation and Novel Roles of RNA. Front Cell Neurosci 13 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel A, Lee HO, Jawerth L, Maharana S, Jahnel M, Hein MY, Stoynov S, Mahamid J, Saha S, Franzmann TM, Pozniakovski A, Poser I, Maghelli N, Royer LA, Weigert M, Myers EW, Grill S, Drechsel D, Hyman AA, and Alberti S 2015. A Liquid-to-Solid Phase Transition of the ALS Protein FUS Accelerated by Disease Mutation. Cell 162 (5): 1066–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feric M, Vaidya N, Harmon TS, Mitrea DM, Zhu L, Richardson TM, Kriwacki RW, Pappu RV, and Brangwynne CP 2016. Coexisting Liquid Phases Underlie Nucleolar Subcompartments. Cell 165 (7): 1686–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brangwynne CP, Mitchison TJ, and Hyman AA 2011. Active liquid-like behavior of nucleoli determines their size and shape in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 (11): 4334–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanulli S, Trnka MJ, Dharmarajan V, Tibble RW, Pascal BD, Burlingame AL, Griffin PR, Gross JD, and Narlikar GJ 2019. HP1 reshapes nucleosome core to promote phase separation of heterochromatin. Nature 575 (7782): 390–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang L, Gao Y, Zheng X, Liu C, Dong S, Li R, Zhang G, Wei Y, Qu H, Li Y, Allis CD, Li G, Li H, and Li P 2019. Histone Modifications Regulate Chromatin Compartmentalization by Contributing to a Phase Separation Mechanism. Mol Cell [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verschure PJ, van der Kraan I, de Leeuw W, van der Vlag J, Carpenter AE, Belmont AS, and van Driel R 2005. In vivo HP1 targeting causes large-scale chromatin condensation and enhanced histone lysine methylation. Mol Cell Biol 25 (11): 4552–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plys AJ, Davis CP, Kim J, Rizki G, Keenen MM, Marr SK, and Kingston RE 2019. Phase separation of Polycomb-repressive complex 1 is governed by a charged disordered region of CBX2. Genes Dev 33 (13–14): 799–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogiyama Y, Schuettengruber B, Papadopoulos GL, Chang JM, and Cavalli G 2018. Polycomb-Dependent Chromatin Looping Contributes to Gene Silencing during Drosophila Development. Mol Cell 71 (1): 73–88 e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tatavosian R, Kent S, Brown K, Yao T, Duc HN, Huynh TN, Zhen CY, Ma B, Wang H, and Ren X 2019. Nuclear condensates of the Polycomb protein chromobox 2 (CBX2) assemble through phase separation. J Biol Chem 294 (5): 1451–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hilbert L, Sato Y, Kimura H, Jülicher F, Honigmann A, Zaburdaev V, and Vastenhouw NL 2018. Transcription organizes euchromatin similar to an active microemulsion. bioRxiv 234112 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo YE, Manteiga JC, Henninger JE, Sabari BR, Dall’Agnese A, Hannett NM, Spille JH, Afeyan LK, Zamudio AV, Shrinivas K, Abraham BJ, Boija A, Decker TM, Rimel JK, Fant CB, Lee TI, Cisse II, Sharp PA, Taatjes DJ, and Young RA 2019. Pol II phosphorylation regulates a switch between transcriptional and splicing condensates. Nature 572 (7770): 543–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zamudio AV, Dall’Agnese A, Henninger JE, Manteiga JC, Afeyan LK, Hannett NM, Coffey EL, Li CH, Oksuz O, Sabari BR, Boija A, Klein IA, Hawken SW, Spille JH, Decker TM, Cisse II, Abraham BJ, Lee TI, Taatjes DJ, Schuijers J, and Young RA 2019. Mediator Condensates Localize Signaling Factors to Key Cell Identity Genes. Mol Cell [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonev B, Mendelson Cohen N, Szabo Q, Fritsch L, Papadopoulos GL, Lubling Y, Xu X, Lv X, Hugnot JP, Tanay A, and Cavalli G 2017. Multiscale 3D Genome Rewiring during Mouse Neural Development. Cell 171 (3): 557–72 e24 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu S, Lv P, Yan Z, and Wen B 2019. Disruption of nuclear speckles reduces chromatin interactions in active compartments. Epigenetics Chromatin 12 (1): 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miron E, Oldenkamp R, Pinto DMS, Brown JM, Faria AR, Shaban HA, Rhodes JDP, Innocent C, de Ornellas S, Buckle V, and Schermelleh L 2019. Chromatin arranges in filaments of blobs with nanoscale functional zonation. bioRxiv 566638 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boettiger AN, Bintu B, Moffitt JR, Wang S, Beliveau BJ, Fudenberg G, Imakaev M, Mirny LA, Wu CT, and Zhuang X 2016. Super-resolution imaging reveals distinct chromatin folding for different epigenetic states. Nature 529 (7586): 418–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu J, Ma H, Jin J, Uttam S, Fu R, Huang Y, and Liu Y 2018. Super-Resolution Imaging of Higher-Order Chromatin Structures at Different Epigenomic States in Single Mammalian Cells. Cell Rep 24 (4): 873–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Belaghzal H, Borrman T, Stephens AD, Lafontaine DL, Venev SV, Weng Z, Marko JF, and Dekker J 2019. Compartment-dependent chromatin interaction dynamics revealed by liquid chromatin Hi-C. bioRxiv 704957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ernst J and Kellis M 2017. Chromatin-state discovery and genome annotation with ChromHMM. Nat Protoc 12 (12): 2478–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sawyer IA, Sturgill D, and Dundr M 2019. Membraneless nuclear organelles and the search for phases within phases. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 10 (2): e1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sawyer IA, Bartek J, and Dundr M 2019. Phase separated microenvironments inside the cell nucleus are linked to disease and regulate epigenetic state, transcription and RNA processing. Semin Cell Dev Biol 90 94–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watson M and Stott K 2019. Disordered domains in chromatin-binding proteins. Essays Biochem 63 (1): 147–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kind J, Pagie L, Ortabozkoyun H, Boyle S, de Vries SS, Janssen H, Amendola M, Nolen LD, Bickmore WA, and van Steensel B 2013. Single-cell dynamics of genome-nuclear lamina interactions. Cell 153 (1): 178–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Di Pierro M, Zhang B, Aiden EL, Wolynes PG, and Onuchic JN 2016. Transferable model for chromosome architecture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113 (43): 12168–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.MacPherson Q, Beltran B, and Spakowitz AJ 2018. Bottom-up modeling of chromatin segregation due to epigenetic modifications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115 (50): 12739–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Michieletto D, Marenduzzo D, and Wani AH 2016. Chromosome-wide simulations uncover folding pathway and 3D organization of interphase chromosomes. bioRxiv 048116 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haddad N, Jost D, and Vaillant C 2017. Perspectives: using polymer modeling to understand the formation and function of nuclear compartments. Chromosome Res 25 (1): 35–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nuebler J, Fudenberg G, Imakaev M, Abdennur N, and Mirny LA 2018. Chromatin organization by an interplay of loop extrusion and compartmental segregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115 (29): E6697–E706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shi G, Liu L, Hyeon C, and Thirumalai D 2018. Interphase human chromosome exhibits out of equilibrium glassy dynamics. Nat Commun 9 (1): 3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumar A and Chaudhuri D 2019. Cross-linker mediated compaction and local morphologies in a model chromosome. J Phys Condens Matter 31 (35): 354001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumar R, Lizana L, and Stenberg P 2019. Genomic 3D compartments emerge from unfolding mitotic chromosomes. Chromosoma 128 (1): 15–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jost D 2014. Bifurcation in epigenetics: implications in development, proliferation, and diseases. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys 89 (1): 010701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Falk M, Feodorova Y, Naumova N, Imakaev M, Lajoie BR, Leonhardt H, Joffe B, Dekker J, Fudenberg G, Solovei I, and Mirny LA 2019. Heterochromatin drives compartmentalization of inverted and conventional nuclei. Nature 570 (7761): 395–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li Y, Danzer JR, Alvarez P, Belmont AS, and Wallrath LL 2003. Effects of tethering HP1 to euchromatic regions of the Drosophila genome. Development 130 (9): 1817–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miele A, Bystricky K, and Dekker J 2009. Yeast silent mating type loci form heterochromatic clusters through silencer protein-dependent long-range interactions. PLoS Genet 5 (5): e1000478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Briand N and Collas P 2018. Laminopathy-causing lamin A mutations reconfigure lamina-associated domains and local spatial chromatin conformation. Nucleus (Calcutta) 9 (1): 216–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bertero A, Fields PA, Smith AST, Leonard A, Beussman K, Sniadecki NJ, Kim DH, Tse HF, Pabon L, Shendure J, Noble WS, and Murry CE 2019. Chromatin compartment dynamics in a haploinsufficient model of cardiac laminopathy. J Cell Biol 218 (9): 2919–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luperchio T, Sauria M, Hoskins V, Wong X, DeBoy E, Gaillard M-C, Tsang P, Pekrun K, Ach R, Yamada N, Taylor J, and Reddy K 2018. The repressive genome compartment is established early in the cell cycle before forming the lamina associated domains. bioRxiv 481598 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nagano T, Lubling Y, Stevens TJ, Schoenfelder S, Yaffe E, Dean W, Laue ED, Tanay A, and Fraser P 2013. Single-cell Hi-C reveals cell-to-cell variability in chromosome structure. Nature 502 (7469): 59–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McCord RP, Nazario-Toole A, Zhang H, Chines PS, Zhan Y, Erdos MR, Collins FS, Dekker J, and Cao K 2013. Correlated alterations in genome organization, histone methylation, and DNA-lamin A/C interactions in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Genome Res 23 (2): 260–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rowley MJ, Lyu X, Rana V, Ando-Kuri M, Karns R, Bosco G, and Corces VG 2019. Condensin II Counteracts Cohesin and RNA Polymerase II in the Establishment of 3D Chromatin Organization. Cell Rep 26 (11): 2890–903 e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hug CB, Grimaldi AG, Kruse K, and Vaquerizas JM 2017. Chromatin Architecture Emerges during Zygotic Genome Activation Independent of Transcription. Cell 169 (2): 216–28 e19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ginno PA, Burger L, Seebacher J, Iesmantavicius V, and Schubeler D 2018. Cell cycle-resolved chromatin proteomics reveals the extent of mitotic preservation of the genomic regulatory landscape. Nat Commun 9 (1): 4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Naumova N, Imakaev M, Fudenberg G, Zhan Y, Lajoie BR, Mirny LA, and Dekker J 2013. Organization of the mitotic chromosome. Science 342 (6161): 948–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hirota T, Lipp JJ, Toh BH, and Peters JM 2005. Histone H3 serine 10 phosphorylation by Aurora B causes HP1 dissociation from heterochromatin. Nature 438 (7071): 1176–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sanborn AL, Rao SSP, Huang S-C, Durand NC, Huntley MH, Jewett AI, Bochkov ID, Chinnappan D, Cutkosky A, Li J, Geeting KP, Gnirke A, Melnikov A, McKenna D, Stamenova EK, Lander ES, and Aiden EL 2015. Chromatin extrusion explains key features of loop and domain formation in wild-type and engineered genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112 (47): E6456–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fudenberg G, Imakaev M, Lu C, and Goloborodko A 2016. Formation of chromosomal domains by loop extrusion. Cell Rep 15 (9): 2038–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Haarhuis JHI, van der Weide RH, Blomen VA, Yanez-Cuna JO, Amendola M, van Ruiten MS, Krijger PHL, Teunissen H, Medema RH, van Steensel B, Brummelkamp TR, de Wit E, and Rowland BD 2017. The Cohesin Release Factor WAPL Restricts Chromatin Loop Extension. Cell 169 (4): 693–707 e14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vian L, Pekowska A, Rao SSP, Kieffer-Kwon KR, Jung S, Baranello L, Huang SC, El Khattabi L, Dose M, Pruett N, Sanborn AL, Canela A, Maman Y, Oksanen A, Resch W, Li X, Lee B, Kovalchuk AL, Tang Z, Nelson S, Di Pierro M, Cheng RR, Machol I, St Hilaire BG, Durand NC, Shamim MS, Stamenova EK, Onuchic JN, Ruan Y, Nussenzweig A, Levens D, Aiden EL, and Casellas R 2018. The Energetics and Physiological Impact of Cohesin Extrusion. Cell 173 (5): 1165–78 e20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wutz G, Varnai C, Nagasaka K, Cisneros DA, Stocsits RR, Tang W, Schoenfelder S, Jessberger G, Muhar M, Hossain MJ, Walther N, Koch B, Kueblbeck M, Ellenberg J, Zuber J, Fraser P, and Peters JM 2017. Topologically associating domains and chromatin loops depend on cohesin and are regulated by CTCF, WAPL, and PDS5 proteins. EMBO J 36 (24): 3573–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schwarzer W, Abdennur N, Goloborodko A, Pekowska A, Fudenberg G, Loe-Mie Y, Fonseca NA, Huber W, Haering CH, Mirny L, and Spitz F 2017. Two independent modes of chromatin organization revealed by cohesin removal. Nature 551 (7678): 51–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rao SSP, Huang SC, Glenn St Hilaire B, Engreitz JM, Perez EM, Kieffer-Kwon KR, Sanborn AL, Johnstone SE, Bascom GD, Bochkov ID, Huang X, Shamim MS, Shin J, Turner D, Ye Z, Omer AD, Robinson JT, Schlick T, Bernstein BE, Casellas R, Lander ES, and Aiden EL 2017. Cohesin Loss Eliminates All Loop Domains. Cell 171 (2): 305–20 e24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gassler J, Brandao HB, Imakaev M, Flyamer IM, Ladstatter S, Bickmore WA, Peters JM, Mirny LA, and Tachibana K 2017. A mechanism of cohesion-dependent loop extrusion organizes zygotic genome architecture. EMBO J 36 (24): 3600–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Takemata N, Samson RY, and Bell SD 2019. Physical and Functional Compartmentalization of Archaeal Chromosomes. Cell 179 (1): 165–79 e18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]