Abstract

CREBBP mutations are highly recurrent in B-cell lymphomas and either inactivate its histone acetyltransferase (HAT) domain or truncate the protein. Herein, we show that these two classes of mutations yield different degrees of disruption of the epigenome, with HAT mutations being more severe and associated with inferior clinical outcome. Genes perturbed by CREBBP mutation are direct targets of the BCL6/HDAC3 onco-repressor complex. Accordingly, we show that HDAC3 selective inhibitors reverse CREBBP mutant aberrant epigenetic programming resulting in: a) growth inhibition of lymphoma cells through induction of BCL6 target genes such as CDKN1A and b) restoration of immune surveillance due to induction of BCL6-repressed IFN pathway and antigen presentation genes. By reactivating these genes, exposure to HDAC3 inhibitor restored the ability of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes to kill DLBCL cells in an MHC class I and II dependent manner, and synergized with PD-L1 blockade in a syngeneic model in vivo. Hence HDAC3 inhibition represents a novel mechanism-based immune-epigenetic therapy for CREBBP mutant lymphomas.

Keywords: CREBBP, HDAC3, Interferon, MHC class II

INTRODUCTION

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma (FL) are the two most frequent subtypes of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. These diseases originate from germinal center B (GCB)-cells; a stage of development that naturally allows for the proliferation and affinity maturation of antigen-experienced B-cells to produce terminally-differentiated memory B-cells or plasma cells. The germinal center (GC) reaction is regulated by B-cell-intrinsic activation and suppression of genes by master regulators such as the BCL6 transcription factor1, and extrinsically via the interaction of GCB-cells with follicular helper T (TFH)-cells and other immune cells within the GC2. The BCL6 transcription factor is critical for GCB-cell development and coordinately suppresses the expression of large sets of genes by recruiting SMRT/NCOR co-repressor complexes containing HDAC33, the LSD1 histone demethylase4, and tethering a non-canonical polycomb repressor 1-like complex in cooperation with EZH25. These genes are normally reactivated to drive GC exit and terminal differentiation in the GC light zone, but the epigenetic control of these dynamically-regulated GC transcriptional programs is perturbed in DLBCL and FL via the downstream effects of somatic mutation of chromatin modifying genes6 (CMG).

The second most frequently mutated CMG in both DLBCL and FL is the CREBBP gene, which encodes a histone acetyltransferase that activates transcription via acetylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27Ac) and other residues. We have previously found that these mutations arise as early events during the genomic evolution of FL and reside in a population of tumor propagating cells, often referred to as common progenitor cells (CPCs)7. We have also noted an association between CREBBP inactivation and reduced expression of MHC class II in human and murine lymphomas7,8. The expression of MHC class II is critical for the terminal differentiation of B-cells through the GC reaction9. The interaction with helper T-cells via MHC class II results in B-cell co-stimulation through CD40 that drives NFκB activation and subsequent IRF4-driven suppression of BCL6. However, in B-cell lymphoma, tumor antigens may also be presented in MHC class II and recognized by CD4 T-cells that drive an anti-tumor immune response10,11. The active suppression of MHC class II expression in B-cell lymphoma may therefore be driven by evolutionary pressure against MHC class II-binding tumor antigens, as recognized in other cancers12. In support of this notion, the reduced expression of MHC class II has been found to be associated with poor outcome in DLBCL13,14.

Recently, MHC class II expression has been defined as an important component of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) related signatures that are predictive of the activity of PD-1 neutralizing antibodies14–17. This is consistent with a prominent role for CD4 T-cells in directing anti-tumor immunity and responses to immunotherapy18. Despite this, current immunotherapeutic strategies largely rely on the pre-existence of an inflammatory microenvironment for therapeutic efficacy. Here, we have characterized the molecular consequences of CREBBP mutations and identified BCL6-regulated cell cycle, differentiation, and IFN signaling pathways as core features that are aberrantly silenced at the epigenetic and transcriptional level. We show that HDAC3 inhibition specifically restores these pathways thus suppressing growth and most critically enabling T-cells to recognize and kill lymphoma cells. Together, these highlight multiple mechanisms by which selective inhibition of HDAC3 can drive tumor-intrinsic killing as well as activate IFN-γ signaling and anti-tumor immunity which extends to both CREBBP wild-type and CREBBP mutant tumors.

RESULTS

CREBBPR1446C mutations function in a dominant manner to suppress BCL6 co-regulated epigenetic and transcriptional programs.

In B-cell lymphomas, the CREBBP gene is predominantly targeted by point mutations that result in single amino acid substitutions within the lysine acetyltransferase (KAT) domain7,19, with a hotspot at arginine 1446 (R1446) that leads to a catalytically inactive protein20,21. However, all of the prior studies characterizing the effects of CREBBP mutation have been performed using knock-out or knock-down of Crebbp, resulting in loss-of-protein (LOP)8,19,22–25. Furthermore, mutations of R1446 have not been documented in any lymphoma cell line. We therefore opted to investigate whether there may be unique functional consequences of KAT domain hotspot mutations of CREBBP. To achieve this, we utilized CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing with two unique guide-RNAs (gRNA) to introduce the most common CREBBP mutation, R1446C, into a CREBBP wild-type cell line bearing the t(14;18)(q21;q32) translocation, RL (Figure 1A). This allowed us to generate clones from each gRNA that had received the constructs but remained wild-type (CREBBPWT), those that edited their genomes to introduce the point mutations into both alleles (CREBBPR1446C), and those that acquired homozygous frameshift mutations resulting in LOP (CREBBPKO) (Figure S1). These isogenic sets of clones differ only in their CREBBP mutation status, and therefore allow for detailed functional characterization in a highly controlled setting.

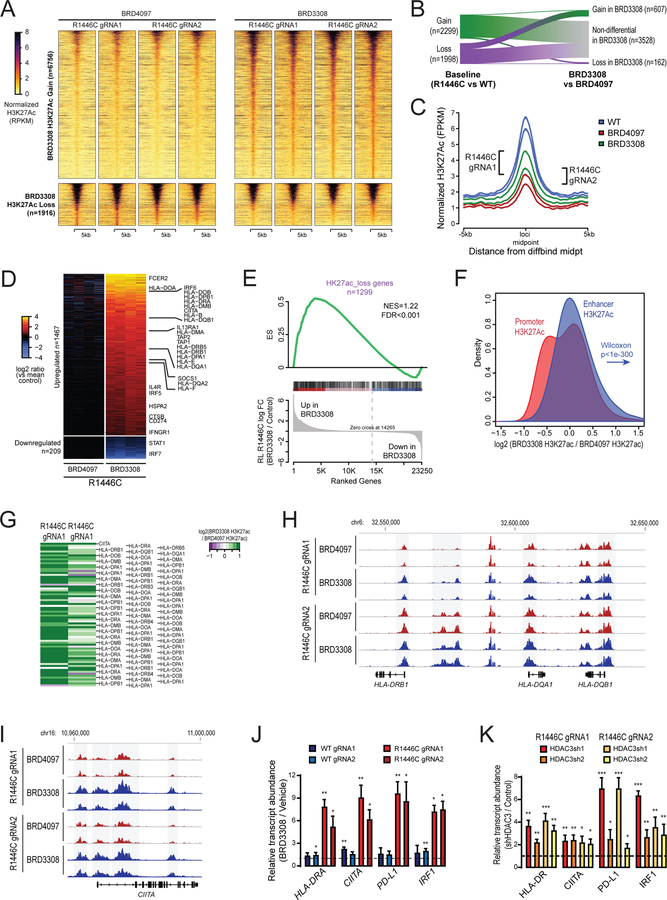

Figure 1: Detailed molecular characterization of CREBBPR1446C and CREBBPKO mutations using isogenic CRISPR/Cas9-modified lymphoma cells.

A) A diagram shows the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing strategy. Two guides were designed that were proximal to the R1446 codon, with PAM sites highlighted in yellow. A single stranded Homologous Recombination (HR) template was utilized that encoded silent single nucleotide changes that interfered with the PAM sites but did not change the protein coding sequence, and an additional single nucleotide change that encoded the R1446C mutation. B) A representative western blot shows that the CREBBPR1446C protein is expressed at similar levels to that of wild-type CREBBP, whereas CREBBPKO results in a complete loss of protein expression as expected. The level of H3K27Ac shows a more visible reduction in CREBBPR1446C cells compared to isogenic CREBBPWT cells than that observed in CREBBPKO cells. C) Quantification of triplicate western blot experiments shows that there is a significant reduction of H3K27Ac in CREBBPR1446C cells compared to CREBBPWT cells (T-test p-value <0.001). A reduction is also observed in CREBBPKO cells, but this was not statistically significant (T-test p-value = 0.106). D) Heat maps show the regions of significant H3K27Ac loss (n=2022, above) and gain (n=2304, below) in CREBBPR1446C cells compared to isogenic WT controls. The regions with reduced H3K27Ac in CREBBPR1446C cells can be seen to normally bear this mark in GCB cells. E) Density plots show that the degree of H3K27Ac loss (above) is most notable in CREBBPR1446C cells compared to isogenic WT cells, while CREBBPKO cells show an intermediate level of loss. Regions with H3K27Ac gain (below) in CREBBPR1446C cells showed fewer changes in CREBBPKO cells. F) A heat map of RNA-seq data shows that there are a similar number of genes with increased (n=766) and decreased (n=733) expression in CREBBPR1446C cells compared to isogenic WT controls. The CREBBPKO cells again show an intermediate level of change, with expression between that of CREBBPWT and CREBBPR1446C cells. G) Gene set enrichment analysis of the genes most closely associated with regions of H3K27Ac gain (above) or loss (below) shows that these epigenetic changes are significantly associated with coordinately increased or decreased expression in CREBBPR144C cells compared to isogenic WT controls, respectively. H) Gene set enrichment analysis shows that genes which were previously found to be down-regulated following shRNA-mediated knock-down of CREBBP in murine B-cells (top) or human lymphoma cell lines (middle) are also reduced in CREBBPR1446C mutant cells compared to CREBBPWT cells. However, the most significant enrichment was observed for the signature of genes that we found to be significantly reduced in primary human FL with CREBBP mutation compared to CREBBP wild-type tumors. I) Hypergeometric enrichment analysis identified sets of genes that were significantly over-represented in those with altered H3K27Ac or expression in CREBBPR1446C cells. This included (i) gene sets associated with CREBBP mutation in primary tumors, (ii) BCL6 target genes, (iii) BCR and IL4 signaling pathways, and (iv) gene sets involving immune responses, antigen presentation and interferon signaling were significantly enriched. J) ChIP-seq tracks of the MHC class II locus on chromosome 6 are shown for isogenic CREBBPWT (blue), CREBBPR1446C (red) and CREBBPKO (orange) cells with regions of significant H3K27Ac loss shaded in grey. A significant reduction can be observed between CREBBPWT and CREBBPR1446C cells, with CREBBPKO cells harboring an intermediate level H3K27Ac over these loci. K) Flow cytometry for HLA-DR shows that reduced H3K27Ac over the MHC class II region is associated with changes of cell surface protein expression. A ~2-fold reduction is observed in CREBBPKO cell compared to CREBBPWT, but a dramatic ~39-fold reduction is observed in CREBBPR1446C cells. L) Kaplan-Meier plots show the failure free survival in 231 previously untreated FL patients according to their CREBBP mutation status. Nonsense/frameshift mutations that create a loss-of-protein (LOP) are associated with a significantly better failure-free survival compared to KAT domain point mutations (KAT P.M.; log-rank P=0.026). M) Kaplan-Meier plots show the overall survival in 231 previously untreated FL patients according to their CREBBP mutation status. Patients with LOP mutations have a trend towards better overall survival, but this is not statistically significant (log-rank P=0.118).

Western blot confirmed that the CREBBPR1446C protein was still expressed and that CREBBPKO mutations resulted in a complete loss of protein expression (Figure 1B). Western blot with densitometry of the H3K27Ac mark revealed significant reduction in H3K27Ac in CREBBPR1446C cells vs isogenic CREBBPWT controls (p<0.001; Figure 1C). Although CREBBPKO cells also showed lower H3K27Ac abundance than isogenic CREBBPWT controls, this reduction was not statistically significant (p=0.106). We performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-sequencing for H3K27Ac to define the physical location of these changes and identify potentially deregulated genes. This revealed 2,022 regions with significantly reduced acetylation, and 2,304 regions with significantly increased acetylation in CREBBPR1446C cells compared to isogenic CREBBPWT controls (Fold change >1.5, Q-value<0.01; Figure 1D and S2, Table S1). This pattern was mirrored by another CREBBP-catalyzed mark, H3K18Ac, and the loss or gain of histone acetylation was also accompanied by gain or loss of H3K27me3, respectively (Figure S3A–D). Regions with loss of H3K27Ac were observed to normally bear this mark in human GCB cells24 (Figure 1D), suggesting that CREBBPR1446C mutations lead to loss of a normal GCB epigenetic program. Notably, CREBBPKO resulted in a reduction of H3K27Ac in these regions also, but at a lower magnitude than that observed with CREBBPR1446C mutations (Figure 1D–E). This was not observed for regions with increased H3K27Ac, which showed little change in CREBBPKO cells.

Using RNA sequencing, we observed broad changes in transcription, with 766 genes showing significantly increased expression and 733 genes showing significantly decreased expression in CREBBPR1446C cells compared to CREBBPWT isogenic controls (Fold change >1.5, Q-value<0.01; Figure 1F; Table S2). The genes that were proximal to regions of H3K27Ac loss showed a coordinate reduction in transcript abundance and vice versa (FDR<0.001, Figure 1G), suggesting that these broad changes in transcription are directly linked to altered promoter/enhancer activity as a result of differential H3K27Ac. Importantly, we observed significant enrichment of the transcriptional signature induced by shRNA knock-down of CREBBP in murine B-cells or human DLBCL cell lines8 (Figure 1H). However, an even more significant enrichment was observed for the signature of genes we defined as being lost in association with CREBBP mutation in primary human CREBBP mutant FL B-cells7 (FDR<0.001, Figure 1H). Consistent with our CRISPR cell line results, primary FL B-cells with CREBBP LOP mutations were observed to have significantly less repression of this signature by single sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) compared to those with CREBBP KAT domain mutation (P = 0.039; Figure S4).

We used epigenetic and transcriptional profiles and hypergeometric analysis to gain insight into biological functions disrupted by CREBBPR1446C mutations (Figure 1I, Table S3–4). This confirmed a significant enrichment of genes downregulated in CREBBP mutant lymphoma patients, and further revealed an enrichment of BCL6-SMRT and BCL6 targets, consistent with the proposed role of CREBBP in opposing BCL6 mediated transcriptional repression. The biological functions of these genes included B-cell receptor (BCR) and NFκB signaling in addition to interferon signaling and antigen presentation (Figure 1I). In line with the enrichment of antigen presentation pathways and the genome-wide differences in H3K27Ac patterning, we observed more severe reduction of H3K27Ac over the MHC class II locus in CREBBPR1446C vs CREBBPKO cells (Figure 1J). This was associated with a ~2-fold reduction of cell surface MHC class II in CREBBPKO cells compared to isogenic CREBBPWT controls, but a ~37-fold reduction in CREBBPR1446C cells (Figure 1K). Notably, EP300 is expressed at a high level in all of the CRISPR modified cell lines and ChIP-qPCR showed that the MHC class II locus is bound by both CREBBP and EP300 in these cells (Figure S5A–C). Moreover, inhibition of EP300 activity in CREBBPKO cells reduced the expression of MHC class II to levels similar to that in CREBBPR1446C cells (Figure S5D), suggesting that the redundant activity of EP300 may partially sustain MHC class II expression in CREBBPKO cells. These data further support a stronger epigenetic and transcriptional suppression of BCL6 target genes, including those involved in antigen presentation, with CREBBPR1446C mutations compared to CREBBPKO.

To confirm that the CREBBP KAT mutation is biologically active in primary GC B-cells in a similar manner to that observed in CRISPR engineered cell lines, we generated a novel genetically engineered mouse model with cre-inducible expression of CrebbpR1447C (equivalent to human R1446C). The endogenous Crebbp locus was engineered to switch from wild-type to mutant gene expression using a floxed inversion cassette (Figure S6A). These animals were crossed to mice engineered for the Cγ1-cre allele to specifically induce recombination in GC B-cells and bone marrow transplanted into irradiated CD45.1 recipients (Figure S6B and C). Transplanted mice were immunized with sheep red blood cells and sacrificed 10 days later when the GC reaction is at its peak (Figure S6C), whereupon flow cytometry was performed to assess B-cell populations. As expected, there was no perturbation of earlier stages of B-cell development (Figure S6D and E). Cre recombination was validated in sorted GC B-cells (Figure S6F). Cγ1Cre;CrebbpR1447C/+ GC B-cells showed significantly reduced MHC class II expression compared to Cγ1Cre;Crebbp+/+ controls (P=0.02, Figure S6G), whereas (as expected) there was no difference in MHC II among naïve B-cells from either genotype (Figure S6H). Finally, Cγ1Cre;CrebbpR1447C/+ mice manifested significantly skewed light-zone:dark-zone ratio in favor of increased dark-zone cells (P=0.01; Figure S6I–L), which are the cells that most reflect the actions of BCL6, although the overall abundance of GC B-cells was not increased (Figure S6M and N). These results confirm in primary cells our MHC class II findings from CRISPR/Cas9-edited clones and hence their value as a platform for mechanistic studies.

Finally, mutations of CREBBP have been previously associated with adverse outcome in FL and are incorporated into the M7-FLIPI prognostic index26. However, in these analyses, all CREBBP mutations were considered collectively without discriminating between KAT domain point mutations or nonsense/frameshift LOP mutations. We therefore re-evaluated these data in light of our observed functional differences between these mutations. This showed that there was a significant difference in failure-free survival (Figure 1L) between these two classes of CREBBP mutations. This was not significant for overall survival (Figure 1M). Specifically, patients bearing KAT domain point mutations in CREBBP (22% of which were R1446 mutations) had a significantly reduced failure-free survival compared to patients with LOP mutations in CREBBP (Log-Rank P=0.026), with no other clinical factors being significantly different between these groups (Table S5). Collectively, these results provide the first direct experimental description of the role of CREBBPR1446C mutations in lymphoma B-cells. Our data suggest that CREBBP KAT domain mutations may have a potential dominant repressive function on loci that can be targeted by redundant acetyltransferases, thereby driving a more profound molecular phenotype that is associated with a worse patient outcome.

Synthetic dependence on HDAC3 in CREBBP-mutant DLBCL is independent of mutation subtype.

Our genomic analysis showed that BCL6 target genes were significantly enriched amongst those with reduced H3K27Ac and gene expression in CREBBPR1446C cells. We therefore evaluated CREBBP and BCL6 binding over these regions using data from normal GC B-cells24 and found that the regions with CREBBPR1446C mutation-associated H3K27Ac loss are bound by both proteins at significantly higher levels than H3K27Ac peaks that remain unchanged with CREBBP mutation (CREBBP Wilcoxon P=1.2−41, BCL6 Wilcoxon P=2.83−52) or peaks with increased H3K27Ac in CREBBPR1446C mutants (CREBBP Wilcoxon P=3.01−137, BCL6 Wilcoxon P=3.17−128; Figure 2A). This suggests that these genes may be antagonistically regulated by CREBBP and BCL6, the latter of which mediates gene repression via recruitment of HDAC3-containing NCOR/SMRT complexes3,27. The epigenetic suppression of gene expression in CREBBP mutant cells may therefore be dependent upon HDAC3-mediated suppression of BCL6 target genes. Using a selective HDAC3 inhibitor, BRD330828, we found that CREBBPR1446C and CREBBPKO clones showed greater sensitivity to HDAC3 inhibition compared to isogenic WT controls in cell proliferation assays (Figure 2B). We confirmed this as being an on-target effect of BRD3308 by performing shRNA knock-down of HDAC3 and observing a greater effect on cell proliferation in CREBBPR1446C cells compared to isogenic controls (Figure 2C and S7). Moreover, HDAC3 inhibition was able to efficiently promote the accumulation of H3K27Ac in a dose-dependent manner in both CREBBPWT and CREBBPR1446C cells, as compared to the inactive chemical control compound BRD4097 (Figure 2D). This suggests that the increased sensitivity to HDAC3 inhibition in CREBBPR1446C cells may be linked with an acquired addiction to an epigenetic change driven by CREBBP mutation. We posited that one of these effects may be the suppression of p21 (CDKN1A) expression, which is a key BCL6 target gene29 that has reduced levels of H3K27Ac in both CREBBPR1446C and CREBBPKO cells (Figure 2E). In support of this, we observed a marked induction of p21 expression by BRD3308 (Figure 2F) and observed that shRNA-mediated silencing of p21 partially rescued the effect of BRD3308 on cell proliferation (Figure 2G). Therefore CREBBP mutations, regardless of type, sensitize cells to the effects of HDAC3 inhibition in part via the induction of p21.

Figure 2: Synthetic dependence upon BCL6 and HDAC3 in CREBBP mutant cells.

A) A heat map shows that regions with reduced H3K27Ac in CREBBPR1446C cells compared to CREBBPWT cells (above) are bound by both CREBBP and BCL6 in normal germinal center B-cells. This binding is not observed over regions with increased H3K27Ac in mutant cells. B) Isogenic CREBBPR1446C and CREBBPKO cells have a greater sensitivity to BRD3308, a selective HDAC3 inhibitor, compared to CREBBPWT cells. C) Knock-down of HDAC3 with two unique shRNAs shows a similar preference towards limiting cell proliferation in CREBBPR1446C cells compared to WT. Data are shown relative to control shRNA in the same cell lines (*P<0.05, ***P<0.001). D) Representative western blots show a dose-dependent increase in H3K27Ac in both CREBBPWT and CREBBPR1446C cells treated with BRD3308, compared to the control compound BRD4097. E) ChIP-seq tracks of H3K27Ac show that CREBBPKO and CREBBPR1446C both have reduced levels over the CDKN1A locus compared to isogenic CREBBPWT cells. Regions that are statistically significant are shaded in grey. F) A representative western blot shows that CDKN1A is induced at the protein level by treatment with 10μM BRD3308 in both CREBBPWT and CREBBPR1446C cells. G) Knock-down of CDKN1A (p21) using two unique shRNAs partially rescued the proliferative arrest of cells treated with BRD3308. This rescue was more significant in CREBBP mutant cells compared to wild-type. Data are displayed relative to vehicle-treated cells (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). H) The difference in sensitivity to BRD3308 between CREBBP wild-type (blue) and CREBBP mutant (yellow to red) was validated in a large panel of DLBCL cell lines. I) The effective dose 50 (ED50) concentrations for each cell line from (H) are shown, colored by CREBBP mutation status. The ED50s for CREBBP mutant (red) cell lines was significantly lower than that observed for CREBBP wild-type cell lines (blue; T-test P=0.002). J) Gene set enrichment analysis of ‘Germinal Center Terminal Differentiation’ signature genes shows that these genes are coordinately induced in both CREBBP wild-type (above) and mutant (below) DLBCL cell lines by BRD3308 treatment compared to control.

We aimed to confirm this trend using a larger panel of DLBCL cell lines with either WT (n=6) or mutant CREBBP (n=6). This revealed a significantly lower ED50 to BRD3308 in CREBBP mutant compared to WT cell lines (p=0.002, Figure 2H–I). We did not observe this trend using the non-specific HDAC inhibitors, Romidepsin and SAHA (Figure S8). Notably, none of these cell lines harbor KAT domain missense mutations of CREBBP, providing further evidence that sensitivity to HDAC3 selective inhibition is independent of mutation type (i.e. KAT domain missense vs nonsense/frameshift). Furthermore, we also observed the induction of p21 expression and apoptosis in CREBBP wild-type cell lines, although to a lesser degree (Figure S9). To gain greater insight into this, we performed RNA-sequencing of CREBBP wild-type (OCI-Ly1) and mutant (OCI-Ly19, OZ) cell lines treated with BRD3308. Notably, the ability of HDAC3 inhibition to induce the expression of genes involved in the terminal differentiation of B-cells was conserved in both wild-type and mutant cell lines (Figure 2J). These results are consistent with the role of BCL6 in controlling checkpoints, terminal differentiation and other functions1 and points towards induction of these transcriptional programs as contributing to the anti-lymphoma response induced by HDAC3-inhibition in both the CREBBP WT and mutant settings. Although targetable by HDAC3 inhibition in wild-type cells, the BCL6-HDAC3 target gene set is more significantly perturbed in the context of CREBBP mutation leading to an enhanced cell-intrinsic effect of HDAC3 inhibition.

HDAC3 inhibition is active against primary human DLBCL

Our observation that HDAC3 inhibition can affect both CREBBP mutant and wild-type B-cells led us to test its efficacy in primary patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models of DLBCL. To achieve this, we first expanded CREBBP wild-type tumors in vivo and transitioned them to our novel in vitro organoid system for exposure to BRD330830. All tumors that were tested showed a dose-dependent reduction in cell viability when cultured with BRD3308, compared to the vehicle control (Figure 3A). We therefore treated 3 of these CREBBP wild-type tumors in vivo with either 25mg/kg or 50mg/kg of BRD3308, which led to a significant reduction in growth of PDX tumors treated with either dose compared to vehicle control (Figure 3B). We were only able to obtain a single primary human CREBBP mutant (R1446C) DLBCL PDX model, which could only be grown by renal capsule implantation. Treatment of these tumors with 25mg/kg BRD3308 and monitoring by weekly magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 3C) showed a significant reduction in growth compared to vehicle control treated tumors (Figure 3D). In line with our cell line models, quantitative PCR analysis of treated PDX tumors showed an induction of BCL6 target genes with a role in B-cell terminal differentiation, including IRF4, PRDM1, CD138 and CD40 compared to vehicle-treated tumors (Figure S10). Therefore, selective inhibition of HDAC3 may be a rational approach for targeting the aberrant epigenetic silencing of BCL6 target genes in primary human B-cell lymphoma.

Figure 3: BRD3308 is effective in primary DLBCL.

A) The sensitivity of primary DLBCL tumors to BRD3308 was evaluated by expanding them in vivo, followed by culture in our in vitro organoid model with different concentrations of BRD3308. A dose-dependent decrease in cell viability was observed in all 6 tumors with increasing concentrations of BRD3308. B) Treatment of 3 unique DLBCL xenograft models in vivo with 25mg/kg (green) or 50mg/kg (orange) of BRD3308 significantly reduced tumor growth compared to vehicle (black) (**P<0.01; ***P<0.001). C) Representative MRI images of renal capsule implanted PDX tumors from a CREBBPR1446C mutant DLBCL at the beginning (day 0) and day 14 of treatment. Tumor is outlined in yellow. D) Quantification of tumor volume by MRI images, normalized to the pre-treatment volume for the same tumor, shows that BRD3308 treatment significantly reduces tumor growth (*P<0.05, **P<0.01).

Selective inhibition of HDAC3 reverts the molecular phenotype of CREBBP mutations.

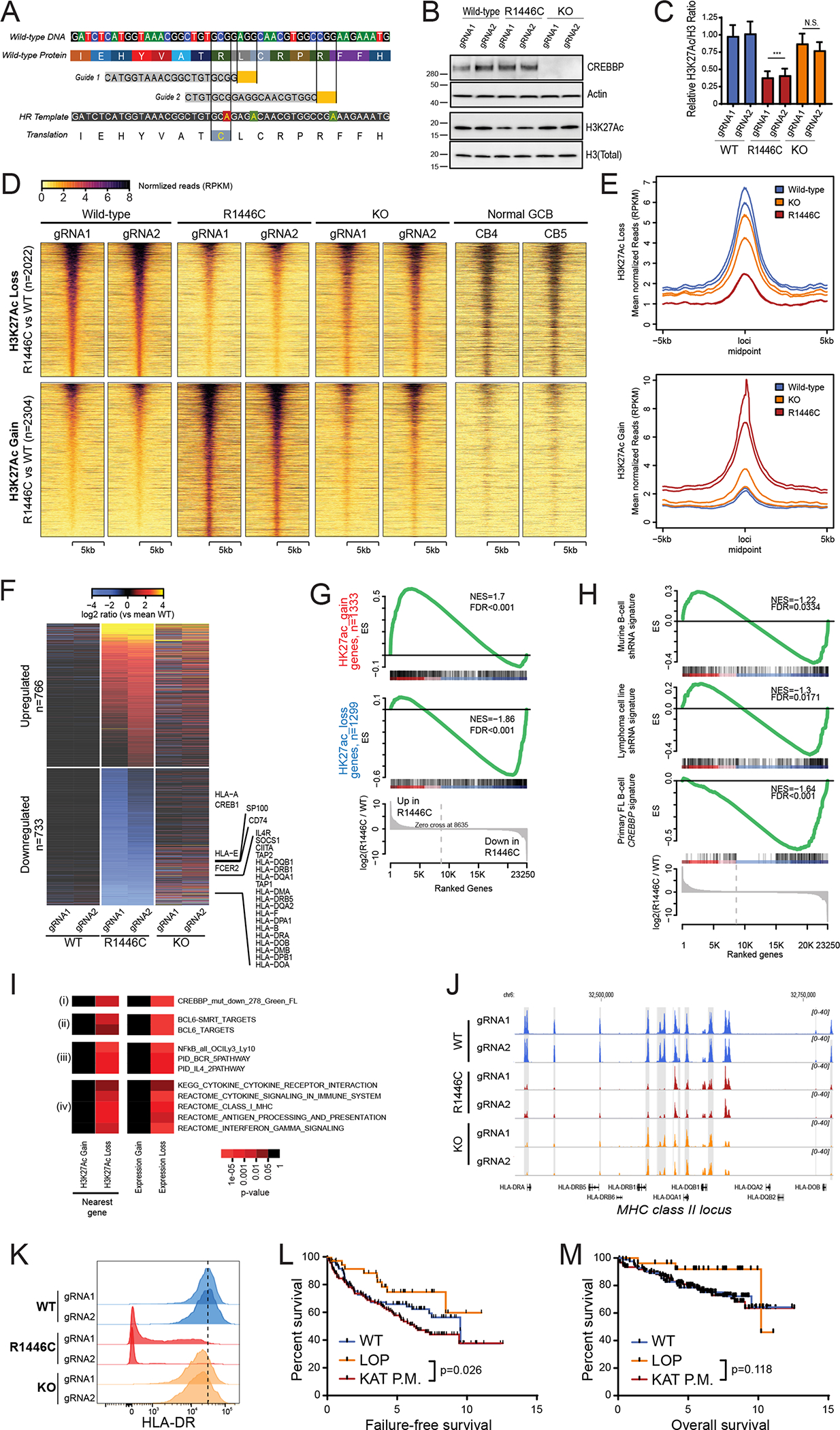

We aimed to take a deeper look at the molecular consequences of HDAC3 inhibition by performing H3K27Ac ChIP-seq and RNA-seq of CREBBPR1446C mutant cells after exposure to BRD3308, as compared to the inactive negative control compound BRD4097. This showed that selective HDAC3 inhibition promoted the gain of H3K27Ac over a broad number of regions (n=6756, Figure 4A). Strikingly, HDAC3 inhibition significantly either restored or further increased the abundance of H3K27Ac at 28% (558/1975) of sites that became deacetylated in CREBBPR1446C (hypergeometric enrichment P = 3.02−178), consistent with the role of HDAC3 in opposing CREBBP functions (Figure 4B). Indeed, a more quantitative analysis indicated HDAC3 inhibition coordinately increased the level of H3K27Ac over the same loci that showed reduced levels in CREBBPR1446C compared to CREBBPWT cells, although this restoration of H3K27Ac was not sufficient to completely revert the epigenomes of CREBBPR1446C cells to the level that was observed in CREBBPWT cells (Figure 4C). In line with the role of HDAC3 and BCL6 in transcriptional repression, BRD3308 induced an expression profile that was markedly skewed towards gene upregulation (n=1467 vs 208 genes downregulated; Figure 4D; Table S6–7), including interferon-responsive genes such as antigen presentation machinery and PD-L1 (CD274). Notably, the genes with increased expression following HDAC3 inhibition were significantly enriched for those that lose H3K27Ac in CREBBPR1446C compared to WT (FDR<0.001, Figure 4E), further supporting the conclusion that HDAC3 inhibition directly counteracts changes associated with CREBBP mutation. A quantitative assessment of ChIP-seq signal indicated that enhancers manifested greater gain of H3K27Ac as compared to promoters in cells exposed to HDAC3i (Wilcoxon P<0.001; Figure 4F), although MHC class II genes also showed coordinate increases in promoter H3K27Ac (Figure 4G). Analysis of critical gene loci that are deregulated by CREBBP mutation, such as the MHC class II gene cluster and CIITA, exemplify this induction of H3K27ac (Figure 4H–I). We validated the increased H3K27Ac and expression of these genes in independent experiments wherein CREBBPR1446C or isogenic control cells were treated with BRD3308 or vehicle, H3K27Ac was measured by ChIP-qPCR (Figure S11), and transcript abundance measured by qPCR (P<0.001, Figure 4J). We further validated that this was an on-target effect of BRD3308 by performing shRNA-mediated knock-down of HDAC3, which resulted in the increased expression of these genes relative to control shRNA (Figure 4K). Together these data indicate that the aberrant mutant-CREBBP epigenetic and transcriptional program can be restored by selective pharmacologic inhibition of HDAC3.

Figure 4: HDAC3 inhibition counteracts the molecular phenotype of CREBBP mutation.

A) A heat map shows the regions with significantly increased (above, n=6756) or decreased (below, n=1916) H3K27Ac in CREBBPR1446C cells treated with BRD3308 compared to those treated with the control compound, BRD4097. Experimental duplicates are shown for each clone. B) A river plot show that a large fraction of the regions with significantly reduced H3K27Ac in CREBBPR1446C cells compared to CREBBPWT cells had significantly increased H3K27Ac following BRD3308 treatment. C) A density plot shows the regions with reduced H3K27Ac in CREBBPR1446C compared to CREBBPWT cells. The level of H3K27Ac over these regions is increased in CREBBPR1446C cells treated with BRD3308 compared to control (BRD4097), but does not reach the level observed in CREBBPWT cells. D) A heat map shows the genes with increased (above, n=1467) or decreased expression (below, n=209) following BRD3308 treatment. Duplicate experiments are shown for each of the two CREBBPR1446C clones. Interferon-responsive genes, including those with a role in antigen processing and presentation, can be observed to increase in expression following BRD3308 treatment. E) Gene set enrichment analysis shows that the set of genes with reduced H3K27Ac in association with CREBBP mutation has coordinately increased expression following BRD3308 treatment. F) A density plot illustrates the relative change in promoter (red) and enhancer (blue) H3K27Ac following treatment with BRD3308, with the enhancer distribution being significantly more right-shifted (increased) compared to promoter regions. G) A heat map shows the change in H3K27Ac at the promoter regions of MHC class II genes following BRD3308 treatment of CREBBPR1446C cells, showing a coordinate increase. H-I) Regions with significantly increased H3K27Ac (shaded in grey) included those within the MHC class II and CIITA gene loci. J) The increased expression of candidate genes within the interferon signaling and antigen presentation pathways was confirmed by qPCR. Increased expression was observed in both CREBBPWT and CREBBPR1446C cells following BRD3308 treatment, but the level of induction was much higher in CREBBPR1446C cells. Data are shown relative to vehicle treated cells (T-test *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). K) The on-target role of HDAC3 in the induction of candidate genes was confirmed by shRNA-mediated knock-down of HDAC3 and qPCR analysis of gene expression. Knock-down of HDAC3 was able to induce the expression of all genes, which is shown relative the control shRNA (T-test *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001).

HDAC3 inhibition counteracts BCL6 target gene repression in lymphoma cells including IFN response, irrespective of CREBBP mutation status.

IFN signaling and antigen presentation genes have not been well investigated as downstream targets of BCL6-HDAC3 complexes, but were enriched in genes suppressed by CREBBP mutation and restored by HDAC3 inhibition. Given their critical role in anti-tumor immunity, we evaluated whether HDAC3 inhibition may be sufficient to restore or promote the expression of these BCL6-repressed immune signatures. Using MHC class II protein expression on CREBBPR1446C mutant cells as a proxy for the CREBBP/BCL6 counter-regulated IFN signaling pathway, we evaluated the activity of HDAC inhibitors for promoting the expression of immune response genes. Although HDAC inhibitors with broader specificities were able to induce MHC class II expression, selective inhibition of HDAC3 was sufficient for the robust and maximal (>10-fold) restoration of MHC class II expression in CREBBPR1446C cells (Figure 5A and S12) in line with our observation that these genes are silenced by BCL6/HDAC3 complexes. These selective inhibitors each show some inhibition of other HDACs28, and their activity in opposing BCL6 function may in part be linked to inhibition of HDAC1/2 which are recruited by BCL6 via CoRest and NuRD4,31,32. However, HDAC1/2 have important functions in normal hematopoiesis33, and hence compounds that target these enzymes induce toxic effects against these cells that are not elicited by BRD33082929, suggesting that selective inhibition of HDAC3 may limit hematological toxicities that are observed with pan-HDAC inhibitors. Furthermore, while some of the less specific HDAC inhibitors were toxic to normal human CD4 and CD8 T-cells, the selective inhibition of HDAC3 was not (Figure 5B and S13). This suggests that selective HDAC3 inhibition may be capable of eliciting immune responses by on-target on-tumor induction of antigen presentation without on-target off-tumor killing of T-cells.

Figure 5: HDAC3 inhibition induces interferon signaling and antigen presentation in both CREBBP wild-type and mutant cells.

A) Flow cytometry was performed for HLA-DR following exposure to a selection of HDAC inhibitors at 10μM for 72h. This shows that HDAC inhibitors with a range specificities are able to induce MHC class II, but HDAC3 selective inhibition using BRD3308 is sufficient for this effect. B) Dose titrations of histone deacetylase inhibitors from (A) with peripheral blood CD4 and CD8 T-cells from healthy donors. C) A heat map of interferon responsive and antigen presentation genes from RNA-seq data shows an increased expression in both CREBBPWT and CREBBPR1446C cells. Data represent duplicate experiments for each clone and are normalized to control treated cells from the same experiment. D) Gene set enrichment analysis of the genes that have reduced H3K27Ac in CREBBPR1446C cells shows that the expression of these same genes are coordinately increased by BRD3308 treatment in CREBBPWT cells. E) A heat map of hypergeometric enrichment analysis results of RNA-seq data shows that BRD3308 induces the induction of similar gene sets in both CREBBPWT and CREBBPR1446C cells. F) A density strip plot, normalized to the mean expression in control (BRD4097)-treated CREBBPWT cells shows the relative expression of the set of genes with reduced H3K27Ac in CREBBPR1446C cells. This shows that these genes are induced by BRD3308 in CREBBPWT cells, resulting in expression levels greater than baseline. Further, CREBBPR1446C cells can be observed to start below baseline, with the induction by BRD3308 resulting in expression levels similar to that observed in control treated CREBBPWT cells. The 4 samples per condition represent duplicate experiments in each of the two clones for each genotype. G) The firefly luciferase luminescence of two unique IRF1 reporters (R1 and R2) is shown, normalized to renilla luciferase from a control vector and shown as fold change compared to untreated cells. CREBBPWT cells show increased IRF1 activity following IFN-γ treatment (positive control; grey), but not following treatment with BRD3308 (green). In contrast, CREBBPR1446C cells show increased IRF1 activity following BRD3308 treatment, to a level that is similar to that observed with IFN-γ treatment. (T-test vs control-treated cells, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). H) The role of IFN-γ in inducing MHC class II expression following BRD3308 in CREBBPR1446C cells was assessed with a blocking experiment. Blocking IFN-γ with a neutralizing antibody (αIFN-γ) significantly reduced the induction of MHC class II, as measured by flow cytometry for HLA-DR, but the induction by BRD3308 with α IFN-γ remained significantly higher than vehicle with αIFN-γ (T-test, ***P<0.001).

Based upon our observations with MHC class II, the magnitude of this induction appeared to be dependent upon the baseline of expression. We therefore hypothesized that CREBBP mutation status may determine the baseline expression for IFN and antigen presentation pathways, but may not be a prerequisite for this response due to the conserved activity of BCL6/HDAC3 in regulating this axis in WT cells. We comprehensively evaluated this theory using our RNA-seq data from CREBBPWT and CREBBPR1446C cells treated with either the HDAC3 inhibitor, BRD3308, or inactive control compound, BRD4097. Consistent with our observations of MHC class II protein expression, BRD3308 treatment coordinately induced the transcript expression of MHC class II and IFN pathway genes in both CREBBPWT and CREBBPR1446C CRISPR-edited cells (Figure 5C). This trend included a significant enrichment for the genes that were epigenetically suppressed in association with CREBBP mutations, resulting in their significant increase in expression in CREBBPWT cells (Figure 5D) similar to our observations from CREBBPR1446C cells (Figure 4E). Moreover, we observed similar enrichment of transcriptionally-induced pathways in both CREBBPWT and CREBBPR1446C cells that included the same pathways that were suppressed by CREBBP mutation (Figure 5E; Tables S7, S8, S9 and S10). Consistent with the almost exclusive function of HDAC3 as a BCL6 corepressor in GC B-cells3, and the importance of BCL6 activity in both CREBBP WT and mutant cells, we observed highly significant enrichment for genes regulated by BCL6-SMRT complexes among genes with induced H3K27Ac and expression after BRD3308 treatment (Figure 5E). Also significantly enriched were canonical BCL6 target gene sets such as p53 regulated genes, and signaling through BCR, CD40 and cytokines like IL4 and IL10. Finally we observed significant enrichment for BCL6 target gene sets linked to IFN signaling, antigen presentation via MHC class II and PD1 signaling.

Although there were conserved patterns of gene activation in both CREBBPWT and CREBBPR1446C cells, we observed that the magnitude of this induction was greatest in CREBBPR1446C cells, which started from a lower baseline of expression linked to mutation-associated epigenetic suppression (Figure 5F). We identified IRF1 as a BCL6-regulated transcription factor that is critical for interferon responses, and is induced by HDAC3 inhibition CREBBPWT and CREBBPR1446C cells (Figure 5C). We therefore hypothesized that IRF1 may contribute to the different magnitude of induction in MHC class II genes following HDAC3 inhibition in these two genetic contexts. We investigated this by measuring IRF1 activity in a luciferase reporter assay in CREBBPWT and CREBBPR1446C mutant cells. Treatment of CREBBPR1446C cells with BRD3308 led to a significant increase of IRF1 activity that was similar in magnitude to that induced by IFN-γ treatment (Figure 5G). In contrast, this effect was not observed in isogenic CREBBPWT control cells following HDAC3 inhibition, despite these cells showing similarly increased IRF1 activity in response to IFN-γ treatment. Exposing CREBBPR1446C cells to IFN-γ neutralizing antibodies only partially ameliorated MHC class II induction after BRD3308 in CREBBP mutant cells (Figure 5H). This suggests that preferential induction of antigen presentation by HDAC3 inhibition in CREBBP mutant cells likely depends on a combination of mechanisms, including directly opposing BCL6 repression of these genes as well as secondary induction through IFN-γ signaling (which is also directly regulated by BCL6).

HDAC3 inhibition restores MHC class II expression in human DLBCL cell lines and patient specimens.

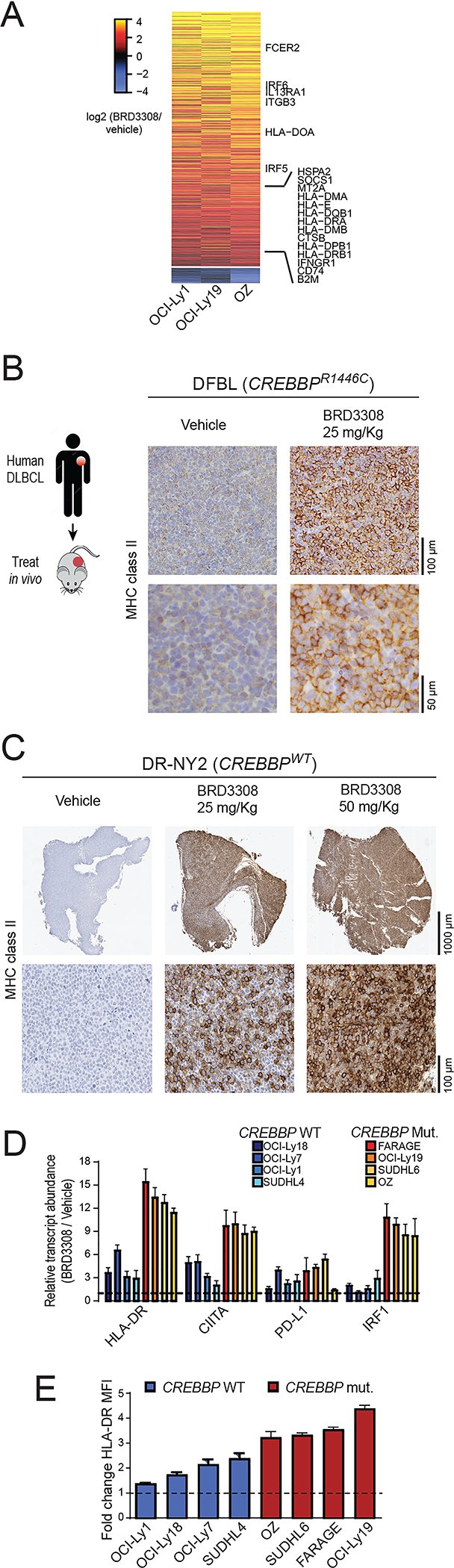

The frequency of MHC class II loss in DLBCL exceeds the frequency of CREBBP mutations in this disease13,21, through unknown mechanisms. The ability of HDAC3 inhibition to induce MHC class II expression in CREBBP WT DLBCL cells may therefore have potentially broad implications for immunotherapy. Using RNA-sequencing data from WT (OCI-Ly1) and mutant (OCI-Ly19 and OZ) DLBCL cell lines (Figure 6A; Tables S11 and S12) and qPCR analysis of PDX tumors treated in vivo (Figure S14A–D), we confirmed that gene expression induced by HDAC3 inhibition was largely conserved in both contexts. The expression of PD-L1 was significantly higher in 4/4 PDX tumors treated with 25mg/kg BRD3308 in vivo compared to vehicle control treated tumors, and MHC class II expression was significantly higher in 3/4 PDX tumors (Figure S14A–D). We extended upon this using immunohistochemical staining for MHC class II in tumors from a CREBBP R1446C mutant PDX model (DFBL; Figure 6B) and a CREBBP wild-type PDX model that was MHC class II negative at baseline (DR-NY2, Figure 6C). In tumors from both models, in vivo treatment with BRD3308 led to a marked induction of MHC class II expression. In a broader panel of CREBBP WT and mutant cell lines, we observed that a core set of genes including HLA-DR, CIITA and PD-L1 had consistently higher expression in BRD3308-treated cells compared to the matched control, but with a higher magnitude of induction in CREBBP mutant cell lines (Figure 6D). This trend was also observed by flow cytometry for MHC class II, which extends upon our observations in CRISPR/Cas9-modified cells by showing a reproducible increase in expression in a larger panel of DLBCL cell lines, and a higher magnitude of induction in CREBBP mutant cell lines (Figure 6E). Together, these results show that selective inhibition of HDAC3 using BRD3308 can promote the expression of IFN and antigen presentation pathway genes in both the CREBBP WT and mutant settings. However, the magnitude of induction is greatest in CREBBP mutant cells owing, in part, to the preferential induction of IRF1 activity in these cells.

Figure 6: Induction of interferon-responsive and antigen presentation genes in DLBCL cell lines and patient-derived xenograft.

A) A heat map shows significantly up-regulated (above) and down-regulated (below) genes in BRD3308-treated DLBCL cell lines that are CREBBP wild-type (OCI-Ly1) or mutant (OCI-Ly19 and OZ), expressed as a log2 ratio to vehicle control treated cells. The observed changes were consistent between wild-type and mutant cell lines, and included up-regulation of interferon-responsive and antigen presentation genes. B) MHC class II was assessed on vehicle control (left) and BRD3308 treated (25mg/kg, right) tumors from a CREBBP R1446C mutant PDX model, showing a visible increase in expression in the BRD3308-treated tumors. These images are representative of 4 tumors per group. C) An MHC class II-negative DLBCL patient derived xenograft model was treated in vivo with either 25mg/kg or 50mg/kg of BRD3308. Immunohistochemical staining was performed for MHC class II, revealing a robust induction of MHC class II expression that was relative to the dose of treatment. These images are representative of 6 tumors per group. D) qPCR was used to validate the gene expression changes of select interferon-responsive genes following BRD3308 treatment across an extended panel of CREBBP wild-type and mutant DLBCL cell lines. These genes were uniformly increased in both genetic contexts, but with a higher magnitude of increase in CREBBP mutant cell lines. One-tailed Students T-test *P<0.05, **P<0.01, **P<0.001. E) The induction of MHC class II expression by BRD3308 was measured in an extended panel of DLBCL cell lines by flow cytometry. Data are plotted as a fold-change of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of HLA-DR in BRD3308-treated vs control-treated cells. We observed uniformly increased MHC class II expression in all cell lines, but with higher magnitude in CREBBP mutants.

HDAC3 inhibition drives T-cell activation and immune responses.

Interferon signaling and antigen presentation are central to anti-tumor immune responses. We therefore investigated whether HDAC3 inhibition could promote antigen-dependent anti-tumor immunity. To test this, we implanted OCI-Ly18 DLBCL cells into NSG mice and once tumors formed we injected human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) including T-cells to expose them to antigens presented by the tumor cells. These are likely to be histocompatibility antigens rather than tumor neoantigens, but are nonetheless presented and recognized through MHC:TCR interactions. After in vivo priming, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were co-cultured in vitro with OCI-Ly18 cells that were pre-treated for 72h with increasing concentrations of BRD3308 to assess the effects on T-cell activation and tumor cell killing (Figure 7A). The DLBCL cells that were epigenetically primed for antigen presentation by BRD3308 significantly increased the activation of CD4 T-cells, as determined by CD69 expression (p<0.05; Figure 7B). As in prior experiments, we observed cell-intrinsic effects of BRD3308 on OCI-Ly18 cells in the absence of TILs, resulting in declining cell viability with higher concentrations of the inhibitor. However, the effects of BRD3308 were markedly and significantly increased in the presence of TILs, consistent with T-cell-directed killing of the tumor cells (P<0.001; Figure 7C). To confirm that this killing was dependent on MHC:TCR interactions we also performed this experiment in the presence of blocking antibodies for MHC class I, MHC class II or both. Blocking one or the other of MHC class I or II rescued some of the cytotoxicity observed in this assay, but blocking both MHC class I and class II together completely abrogated the TIL-associated effect (Figure 7C). These data show that HDAC3 inhibition can potentiate anti-tumor immune responses that are likely to be antigen-dependent because they are driven by MHC:TCR interactions. Our identification of the interferon signaling pathway, and IFN-γ itself, as a central component of the response to HDAC3 inhibition led us to test whether IFN-γ levels may rise as a result of treatment. An ELISPOT analysis of the IFN-γ levels from the TIL and OCI-Ly18 co-culture experiment revealed a striking and significant increase in IFN-γ levels, even at the lowest concentrations of HDAC3 inhibitor (Figure 7D and S15).

Figure 7: HDAC3 inhibition induces antigen-dependent immune responses.

A) A schematic of the generation of antigen-specific T-cells and epigenetic priming of DLBCL cells. A human DLBCL cell line (OCI-Ly18) was engrafted into immunodeficient mice and allowed to establish. Human T-cells were then engrafted, exposing them to tumor antigens prior to harvesting of the tumor-infiltrating T-cell (TIL) fraction. These TILs were cultured with fresh DLBCL cells that had been epigenetically primed with different concentrations of BRD3308, and the cell viability of the DLBCL cells measured after 72h. B) TIL and DLBCL co-culture resulted in activation of the CD4 T-cells in a dose-dependent manner, as measured by flow cytometry for the CD69 activation marker. Data represent the fold change in CD69 expression compared to vehicle treated DLBCL cells (T-test vs DMSO control, *P<0.05). C) The cell viability of DLBCL cells in TIL co-culture experiments was measured by CellTiterBlue assay. Treatment with BRD3308 resulted in some cell killing through cell-intrinsic mechanisms in the absence of TILs (black). The addition of TILs at a 1:1 ratio led to a significant increase in cell death of the DLBCL cells. This was partially reduced by blocking of either MHC class I or MHC class II using neutralizing antibodies. Blocking of MHC class I and class II together completely eliminated the TIL-associated increase in cell death, suggesting that killing was mediated through MHC:TCR interactions. (T-test, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001) D) The production of IFN-γ was measured by ELISPOT and found to increase in cultures with epigenetically-primed DLBCL cells. (T-test vs DMSO control, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001) E) A syngeneic BCL6-dependent lymphoma model for in vivo testing of BRD3308 and PD-L1 blocking antibodies. Splenocytes were taken from Ezh2Y641 x IμBcl6 mice and injected into irradiated wild-type recipients that were treated upon the onset of lymphoma. F) Serum IFN-γ levels measured in mice following treatment. G-N) Representative immunofluorescence images of mouse spleens following treatment and quantification of mean fluorescence intensities from multiple mice for CD8 (G, H), CD4 (I, J), PD-L1 (K, L) and B220 (M, N), showing increased T-cell infiltration following treatment with BRD3308 and cooperation with αPD-L1 in eliminating B220+ tumor cells within the spleen. (T-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001)

Considering the manner in which to best harness the anti-lymphoma immunity effect of HDAC3 inhibitors, we noted that induction of MHC class II is mechanistically linked to IFN-γ associated PD-L1 upregulation, which could potentially limit maximal anti-tumor response. We therefore posited that PD-1/PD-L1 blockade may be an attractive combination regimen. To test this hypothesis we used a murine lymphoma transplantation model in which splenocytes from IμBcl6;Ezh2Y641F mice5 were transplanted into irradiated syngeneic wild-type recipients (Figure 7E). Aggressive tumors formed within these mice, which we treated with either vehicle control, BRD3308 alone, αPD-L1 alone, or a BRD3308 + αPD-L1 combination. Treatment with BRD3308 led to a significant increase in serum IFN-γ within these mice, which was also observed with αPD-L1 treatment and was even further enhanced in an additive manner by the combination treatment (Figure 7F). Immunofluorescent staining for CD4 and CD8 showed significantly increased infiltration within the spleens from BRD3308-treated mice, which was further increased by the combination therapy (Figure 7G–J). The ability of BRD3308 and αPD-L1 combination to increase TILs was likely linked with the IFN-γ-mediated PD-L1 induction that was observed in BRD3308-treated tumors (Figure 7K–L). In line with this interaction, BRD3308 and αPD-L1 each showed a small degree of single-agent efficacy, but the combination led to the most significant reduction in B220 cells within the spleens of tumor-bearing mice (Figure 7M–N). Together these data show that HDAC3 inhibitor-mediated reversal of the BCL6 repressed IFN pathway leads to joint induction of MHC class II and PD-L1, which although eliciting significant anti-tumor immune response, can be further enhanced by combination with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade to yield a more potent immunotherapy strategy that is superior to checkpoint inhibition alone.

DISCUSSION

Precision medicine and immunotherapy have led to significant breakthroughs in a variety of cancers, but have lacked success in B-cell lymphoma. For precision medicine, this is largely due to a paucity of ‘actionable’ genetic alterations or, rather, the lack of current therapeutic avenues to target the mutations that have been defined as being important for disease biology. For immunotherapy, the mechanisms driving lack of response or early progression are not well understood, but are likely to be underpinned by the complex immune microenvironment and genetic alterations that drive immune escape. The exception to both of these statements is the use of PD-1 neutralizing antibodies in classical Hodgkin lymphoma, which opposes genetically-driven immune suppression by the malignant Reed-Sternberg cells through DNA copy number gain of the PD-L1 locus34 and elicits responses in the majority of patients35. This stands as an example of the potential success that could be achieved by the characterization and rational therapeutic targeting of genetic alterations and/or the neutralization of immune escape mechanisms. However, we are not yet able to successfully target some of the most frequently mutated genes or overcome the barriers of inadequate response to immunotherapy in the most common subtypes of B-cell lymphoma. These are important areas of need if we hope to further improve the outcomes of these patients.

The CREBBP gene is mutated in ~15% of DLBCL21 and ~66% of FL7, and is therefore a potentially high-yield target for precision therapeutic approaches. Our use of CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing to generate isogenic lymphoma cell lines that differ only in their CREBBP mutation status allowed us to perform detailed characterization of the epigenetic and transcriptional consequences of these mutations. Using this approach we identified for the first time functional differences between the most frequent KAT domain point mutation, R1446C, and frameshift mutations that result in KO. Although similar regions of the genome showed reduced H3K27Ac in R1446C and KO mutants compared to isogenic WT controls, the magnitude of these changes were markedly reduced in CREBBP KO. This suggests that acetyltransferases such as EP300 may compensate for the loss of CREBBP protein in the setting of CREBBP nonsense/frameshift mutations, consistent with observations of functional redundancy between Crebbp and Ep300 in B-cell specific conditional knock-out mice25,36. But the presence of a catalytically inactive CREBBPR1446C protein may dominantly suppress histone acetylation by preventing the participation of redundant acetyltransferases such as EP300 in transcriptional activating complexes. This yields a more severe epigenetic and transcriptional phenotype in CREBBPR1446C mutants compared to CREBBPKO, and an inferior clinical outcome.

Despite differences in the magnitude of molecular changes between R1446C and KO cells, these mutations yielded a similar degree of synthetic vulnerability to HDAC3 inhibition. This was likely driven by the increased suppression of BCL6 target genes that we observed in both contexts, including CDKN1A (p21). This gene has also been highlighted as a critical nexus in the oncogenic potential of EZH237, which cooperates with BCL6 to silence gene expression5. One of the important mechanisms for BCL6-mediated gene silencing is through the recruitment of HDAC3 as part of the NCOR/SMRT complex3, thereby highlighting HDAC3 inhibition as a rational therapeutic avenue for counteracting BCL6 activity. Virtually all of the HDAC3 corepressor complexes present in DLBCL cells are bound with BCL6, suggesting that HDAC3 inhibitors effect is largely explained by their depression of the subset of BCL6 target genes regulated through this mechanism3. Importantly, as a variety of GCB-derived malignancies rely on BCL6 function independently of CREBBP or EZH2 mutation38,39, opposing this function through HDAC3 inhibition may also be effective in tumors without these genetic alterations. We have shown preliminary evidence in the primary setting using DLBCL PDX models.

One of the important transcriptional programs that is regulated by BCL6 is the interferon signaling pathway3, which we observed to be significantly repressed in CREBBP mutant cells. It has been also long been recognized that IFN-γ cooperates with lymphocytes to prevent cancer development40. Interferon signaling supports T-cell driven anti-tumor immunity via a variety of mechanisms, including the induction of antigen presentation on MHC class II41, and the expression of MHC class II-restricted tumor antigens is required for the spontaneous or immunotherapy-induced rejection of tumors14. We have shown that the selective inhibition of HDAC3 is sufficient for broadly restoring the reduced H3K27Ac and gene expression that is associated with CREBBP mutation, including the interferon signaling and antigen presentation programs. This was in part driven by the increased production of IFN-γ following HDAC3 inhibition, but also via the induced expression and activity of the IRF1 transcription factor. Together, these factors lead to a robust restoration of MHC class II expression on CREBBP mutant cells and drove dose-dependent potentiation of anti-tumor T-cell responses. However, we also noted that the same molecular signature is promoted by HDAC3 inhibition in CREBBP wild-type cells, also with an associated increase of MHC class II expression. As with the cell-intrinsic effects of HDAC3 inhibition, the effects on immune interactions may therefore be active in both CREBBP wild-type and CREBBP mutant cells as a result of the conserved molecular circuitry controlling these pathways in each genetic context.

A variety of HDAC inhibitors were capable of restoring antigen presentation in our models and clinical responses are observed with these agents in relapsed/refractory FL and DLBCL patients. However, grade 3–4 hematological toxicities such as thrombocytopenia, anemia and neutropenia were frequent, and the responses tended not to be durable42,43. We posit that specific inhibition of HDAC3 may be accompanied by reduced toxicity, as HDAC1 and HDAC2 have important roles in hematopoiesis33 and avoiding the inhibition of these HDACs may therefore avoid the undesired hematological effects associated with pan-HDAC inhibition. In line with this, we observed that BRD3308 was less toxic to CD4 and CD8 T-cells than pan-HDAC inhibitors, and was able to elicit MHC-dependent T-cell responses against a CREBBP wild-type DLBCL cell line in vitro. Although these responses are likely driven by histocompatibility antigens rather than tumor neoantigens, it supports the premise that selective HDAC3 inhibition is capable of promoting antigen presentation and immune responses. We also speculate that the clinically-observed lack of durability for HDAC inhibitors may be the result of adaptive immune suppression through mechanisms such as PD-L1 induction, which dampens T-cell responses through the PD-1 receptor44, as well as direct toxicity of pan-HDAC inhibitors to T-cells. We found evidence for adaptive immune suppression within our model systems, showing that HDAC3 inhibition leads to increased IFN-γ production and the upregulation of PD-L1 expression. This is in line with recent observations that PD-L1 (CD274) is a BCL6-supressed gene45, and a well-characterized role for PD-L1 as an IFN-γ-responsive gene44. In other cancers in which a florid antigen-driven immune response and concomitant adaptive immune suppression via PD-L1 exist within the tumor microenvironment, blockade of the PD-1 receptor is an effective therapeutic strategy15,17. Recent studies have also shown that the efficacy of PD-1 blockade is inextricably linked with the existence of an interferon-driven immune response and expression of MHC class II15,17. We have shown some evidence for this in a syngeneic, BCL6 driven murine model of B-cell lymphoma, wherein the combination of HDAC3 inhibition and αPD-L1 led to enhanced levels of CD4 and CD8 T-cell infiltration and clearance of tumor cells. Together, these observations suggest that the greatest potentiation of anti-tumor immunity in GCB-derived malignancies may be achieved through stimulation of interferon signaling and MHC class II expression by HDAC3 inhibition, in combination with the blockade of adaptive immune suppression using PD-L1/PD-1 neutralizing antibodies. However, this concept requires further exploration in future studies.

In conclusion, this work defines a molecular circuit that controls the survival and differentiation of lymphoma B-cells and their interaction with T-cells. This circuit is antagonistically regulated by CREBBP and BCL6, and can be pushed towards promoting tumor cell death and anti-tumor immunity via selective inhibition of HDAC3. This highlights HDAC3 inhibition as an attractive therapeutic avenue, which may be broadly active in FL and DLBCL due to the near-ubiquitous role of BCL6, but which may have enhanced potency in CREBBP mutant tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

For detailed methodology, please refer to the supplementary methods section.

CRISPR/Cas9-modification of lymphoma cells

The RL cell-line (ATCC CRL-2261) was modified by electroporation of one of two unique gRNA sequences in the pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP vector (Addgene plasmid #48138, gift from Feng Zhang)46 with a single-stranded oligonucleotide donor template. Single GFP-positive cells were sorted 3–4 days after transfection, colonies expanded and evaluated for changes in the targeted region using Sanger sequencing. The process was repeated for until point mutants were retrieved from each of the two gRNAs, totaling 742 single clones. Potential off-target sites of each guide RNA were determined by BLAST, and all sites with ≥16/20 nucleotide match to either of the gRNA sequences was interrogated by Sanger sequencing (Table S13). All cells were maintained as sub-confluent culture in RPMI medium with 10% FBS and PenStrep and re-validated by Sanger sequencing prior to each set of experiments. Basic phenotyping of the cell lines is presented in Figure S16A–E.

ChIP-sequencing

Cells were washed and fixed in formaldehyde, and chromatin sheared by sonication. An antibody specific to H3K27Ac (Active Motif) was coupled to magnetic protein G beads, incubated with chromatin overnight, and immunoprecipitation performed. Input controls were reserved for comparison. Nucleosomal DNA was isolated and either used as a template for qPCR (ChIP-qPCR) or to generate NGS libraries using KAPA Hyper Prep Kits (Roche) and TruSeq adaptors (Bioo Scientific) using 6 cycles of PCR enrichment. Libraries were 6-plexed and sequenced with 2×100bp reads on a HiSeq-4000 (Illumina). The data were mapped using BWA, peaks called using MACS2, and differential analyses performed using DiffBind. For gene set enrichment analyses, the gene with the closest transcription start site to the peak was used. The statistical thresholds for significance were q<0.05 and fold-change>1.5.

RNA-sequencing

Total RNA was isolated using AllPrep DNA/RNA kits (Qiagen) and evaluated for quality on a Tapestation 4200 instrument (Agilent). Total RNA (1μg) was used for library preparation with KAPA HyperPrep RNA kits with RiboErase (Roche) and TruSeq adapters (Bioo Scientific). Libraries were validated on a Tapestation 4200 instrument (Agilent), quantified by Qubit dsDNA kit (Life Technologies), 6-plexed, and sequenced on a HiSeq4000 instrument at the MD Anderson Sequencing and Microarray Facility using 2×100bp reads. Reads were aligned with STAR, and differential gene expression analysis performed with DEseq2. The statistical thresholds for significance were q<0.05 and fold-change>2.

Cell proliferation assays

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 50,000 cell/100 μl/well with either vehicle (DMSO 0.1%) or increasing concentrations of drugs. Cell viability was assessed with the fluorescent redox dye CellTiter-Blue (Promega). The reagent was added to the culture medium at 1:5 dilution, according to manufacturer`s instructions. Procedures to determine the effects of certain conditions on cell proliferation and apoptosis were performed in 3 independent experiments. The 2-tailed Student t test and Wilcoxon Rank test were used to estimate the statistical significance of differences among results from the 3 experiments. Significance was set at P < .05. The PRISM software was used for the statistical analyses.

Patient-derived xenograft and in vitro organoid studies.

A CREBBP R1446C mutant tumor (DFBL13727) was obtained from the public repository of xenografts47, expanded for 12 weeks in 1 mouse by surgical implantation into the renal capsule, then implanted into the renal capsule 12 additional mice for efficacy studies. Tumors were allowed to grow for 6 weeks, the size measured by MRI and mice randomized to treatment and control groups to similar average tumor sizes. Mice were treated with BRD3308 (25mg/kg) or vehicle control twice per day, 5 days on and 2 days off for a total of 3 weeks, and tumor size assessed by MRI every 7 days. Two mice per group were euthanized on day 10 and the tumors harvested for biomarker analysis. Mice were cared for in accordance with guidelines approved by the MD Anderson Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

For CREBBP wild-type tumors (NY-DR2, DANA and TONY), six week old female NSG mice were implanted subcutaneously and treatments started when tumors reached 100 mm3. Mice (12/group) were randomized and dosed via oral gavage with BRD3308 (25 mg/kg) or control vehicle (0.5% methyl cellulose, 0.2% tween 80) twice daily for 21 consecutive days. Mice were cared for in accordance with guidelines approved by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Research Animal Resource Center.

For in vitro organoid culture, the tumors were dissociated to single cells, stained with CFSE, washed and mixed with irradiated 40LB cells at a 10:1 ratio of Primary:40LB. The cell mixture was then used to fabricate organoids in a 96-well plate as previously described48, with 20 μL organoids containing 3% silicate nanoparticles and a 5% gelatin in IMDM medium solution. The organoids were cultured in IMDM medium containing 20% FBS supplemented with antibiotics and normocin (Invivogen) for 6 days, doubling the volume of medium after 3 days. The cell mixture was exposed to 4 1:3 serial dilutions of BRD3308 starting at 5 μM or vehicle control (DMSO) in triplicate for 6 days, treating a second time at 3 days. After 6 days of exposure, cell viability and proliferation were assessed by flow cytometry using DAPI staining gating on CFSE-positive cells.

Ex vivo killing assay.

The OCI-LY18 was subcutaneously implanted in NSG mice and allowed to become established before the mice were injected with PBMC. After 2 weeks, the tumors were dissociated to single cells and CD3+ TILs were positively selected. T cells were expanded with a single administration of immunomagnetic microbeads coated with mouse anti-human CD3 and CD28 mAb, rhIL2 and rhIL15 for 5 days. OCI-LY18 cells were treated with either DMSO or 10μM BRD3308 for 3 days, washed and resuspended in fresh media with or without T cells at a ratio of 1:10. For MHC blocking, OCI-LY18 cells treated with 10μg/mL of either isotype Ig, or blocking Ab against HLA-ABC W6/32, HLA-DR/DP/DQ or the combination of the two. After 24 hours co-culture, cell viability was analyzed using CellTiter Blue.

Immunocompetent IμBcl6;Ezh2Y641F model.

6 weeks old female C56BL/6J mice were irradiated at day −1 and 0 with 250 rad, and after 2 hours transplanted with 1 × 106 splenocytes from IμBcl6;Ezh2Y641F mice5 and 0.2 × 106 bone marrow cells from a healthy age-matched donor. Three weeks after transplantation, mice became sick and treatment was initiated with either vehicle or BRD3308 (25 mg/kg twice daily, every day for 21 days) via oral gavage, with or without αPDL1 antibody delivered by intraperitoneal injection (250 μg twice weekly for 4 administration). Mice were monitored daily and euthanized when they became moribund. Spleen and liver where measured, weighed and analyzed by flow cytometry for evaluating the disease. Immunofluorescent staining and imaging were performed at the Molecular Cytology Core Facility of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Sections were stained with either anti- CD4 (R&D Systems, cat#AF554, 2ug/ml) or anti-PD-L1 (R&D Systems cat#AF1019, 2ug/ml) or B220 (BD Biosciences, cat# 550286, 0.3ug/ml) or anti-CD8 (eBiosciences cat# 14–0808, 2.5ug/ml) for 5 hours, followed by 60 minutes incubation with biotinylated horse anti-goat IgG (forCD4 and PD-L1) (Vector cat#BA-9500) or biotinylated goat anti-rat IgG (for CD8 and B220) (Vector labs, cat#BA9400) at 1:200 dilution. The detection was performed with Streptavidin-HRP D (part of DABMap kit, Ventana Medical Systems), followed by incubation with Tyramide Alexa 488 (Invitrogen, cat# B40953), and counterstaining with DAPI (Sigma Aldrich, cat# D9542, 5 ug/ml). The slides were scanned with a Pannoramic Flash P250 Scanner (3DHistech,Hungary) using a 20x/0.8NA objective lens. The fluorescence channels were imaged using DAPI, FITC, and TRITC filters sequentially with manually adjusted exposure times. Images were then exported into .tifs using Caseviewer (3DHistech,Hungary) to be analyzed.

DATA DEPOSITION

The RNA-seq and ChIP-seq data are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession number GSE142357.

Supplementary Material

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE.

We have leveraged the molecular characterization of different types of CREBBP mutations to define a rational approach for targeting these mutations through selective inhibition of HDAC3. This represents an attractive therapeutic avenue for targeting synthetic vulnerabilities in CREBBP mutant cells in tandem with promoting anti-tumor immunity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by R01 CA201380 (MRG), R01 CA055349 (DAS), R01 CA178765 (RGR), U54 OD020355 01 (ES and GI), NCI SPORE P50 CA192937 (AD and AY), the MD Anderson Cancer Center (P30 CA016672) and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (P30 CA008748) NCI CORE Grants, the Chemotherapy Foundation (AMM), the Star Cancer Consortium (AMM), the Jaime Erin Follicular Lymphoma Research Consortium (AMM, MRG, SSN), the Schweitzer Family Fund (MRG), the Futcher Foundation (LN, MRG). HY is a Fellow of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: DAS is a consultant to, and/or has equity in: Eureka, SLS, KLUS, IOVA, PFE, Oncopep. LN receives research support from Celgene, Genentech, Janssen, Karus, Merck, TG Therapeutics and honorarium from Bayer, Celgene, Genentech, Gilead/KITE, Janssen, Juno, Novartis, TG Therapeutics. AY is a consultant to: Bayer, Incyte, Janssen, Merck, Genentech and receives research support from Novartis, J&J, Curis, Roche and BMS. AD receives personal fees from Roche, Corvus Pharmaceuticals, Physicians’ Education Resource, Seattle Genetics, Peerview Institute, Oncology Specialty Group, Pharmacyclics, Celgene, and Novartis and research funding from Roche. SSN reports personal fees and research support from Kite, Merck, and Celgene, research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Poseida, Cellectis, Karus, Acerta Pharma, and Unum Therapeutics, and personal fees from Novartis, Pfizer, Unum Therapeutics, Pfizer, Precision Biosciences, Cell Medica, Allogene, Incyte, and Legend Biotech. J.B. is an employee of AstraZeneca, is on the Board of Directors of Foghorn and is a past board member of Varian Medical Systems, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Grail, Aura Biosciences, and Infinity Pharmaceuticals. J.B. also has performed consulting and/or advisory work for Grail, PMV Pharma, ApoGen, Juno, Lilly, Seragon, Novartis, and Northern Biologics, and he has stock or other ownership interests in PMV Pharma, Grail, Juno, Varian, Foghorn, Aura, Infinity Pharmaceuticals, ApoGen, as well as Tango and Venthera, of which is a co‐founder. He has previously received honoraria or travel expenses from Roche, Novartis, and Eli Lilly. AMM receives research funding from Janssen and Daiichi SAnkyo, is a consultant for Epizyme and Constellation, and is an advisory board member for KDAc Therapeutics. MRG is a consultant to VeraStem Oncology and has stock ownership interest in KDAc Therapeutics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hatzi K & Melnick A Breaking bad in the germinal center: how deregulation of BCL6 contributes to lymphomagenesis. Trends Mol Med 20, 343–352, doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.03.001 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mesin L, Ersching J & Victora GD Germinal Center B Cell Dynamics. Immunity 45, 471–482, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.09.001 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatzi K et al. A hybrid mechanism of action for BCL6 in B cells defined by formation of functionally distinct complexes at enhancers and promoters. Cell reports 4, 578–588, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.016 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatzi K et al. Histone demethylase LSD1 is required for germinal center formation and BCL6-driven lymphomagenesis. Nature immunology 20, 86–96, doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0273-1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beguelin W et al. EZH2 and BCL6 Cooperate to Assemble CBX8-BCOR Complex to Repress Bivalent Promoters, Mediate Germinal Center Formation and Lymphomagenesis. Cancer cell 30, 197–213, doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.07.006 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green MR Chromatin modifying gene mutations in follicular lymphoma. Blood 131, 595–604, doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-08-737361 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green MR et al. Mutations in early follicular lymphoma progenitors are associated with suppressed antigen presentation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112, E1116–1125, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501199112 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang Y et al. CREBBP Inactivation Promotes the Development of HDAC3-Dependent Lymphomas. Cancer discovery 7, 38–53, doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0975 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen CD, Okada T & Cyster JG Germinal-center organization and cellular dynamics. Immunity 27, 190–202, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.009 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khodadoust MS et al. Antigen presentation profiling reveals recognition of lymphoma immunoglobulin neoantigens. Nature 543, 723–727, doi: 10.1038/nature21433 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khodadoust MS et al. B cell lymphomas present immunoglobulin neoantigens. Blood 133, 878–881, doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-06-845156 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marty R, Thompson WK, Salem RM, Zanetti M & Carter H Evolutionary Pressure against MHC Class II Binding Cancer Mutations. Cell 175, 416–428, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.048 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rimsza LM et al. Loss of MHC class II gene and protein expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is related to decreased tumor immunosurveillance and poor patient survival regardless of other prognostic factors: a follow-up study from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Molecular Profiling Project. Blood 103, 4251–4258, doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2365 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alspach E et al. MHC-II neoantigens shape tumour immunity and response to immunotherapy. Nature 574, 696–701, doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1671-8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodig SJ et al. MHC proteins confer differential sensitivity to CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade in untreated metastatic melanoma. Science translational medicine 10, eaar3342, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aar3342 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayers M et al. IFN-gamma-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. The Journal of clinical investigation 127, 2930–2940, doi: 10.1172/JCI91190 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tumeh PC et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 515, 568–571, doi: 10.1038/nature13954 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borst J, Ahrends T, Babala N, Melief CJM & Kastenmuller W CD4(+) T cell help in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nature reviews. Immunology 18, 635–647, doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0044-0 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Ramirez I et al. Crebbp loss cooperates with Bcl2 over-expression to promote lymphoma in mice. Blood 129, 2645–2656, doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-733469 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullighan CG et al. CREBBP mutations in relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature 471, 235–239, doi: 10.1038/nature09727 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pasqualucci L et al. Inactivating mutations of acetyltransferase genes in B-cell lymphoma. Nature 471, 189–195, doi: 10.1038/nature09730 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashwah H et al. Inactivation of CREBBP expands the germinal center B cell compartment, down-regulates MHCII expression and promotes DLBCL growth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619555114 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horton SJ et al. Early loss of Crebbp confers malignant stem cell properties on lymphoid progenitors. Nat Cell Biol 19, 11093–11104, doi: 10.1038/ncb3597 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J et al. The Crebbp Acetyltransferase is a Haploinsufficient Tumor Suppressor in B Cell Lymphoma. Cancer discovery 7, 322–337, doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1417 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer SN et al. Unique and Shared Epigenetic Programs of the CREBBP and EP300 Acetyltransferases in Germinal Center B Cells Reveal Targetable Dependencies in Lymphoma. Immunity 51, 535–547, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.08.006 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pastore A et al. Integration of gene mutations in risk prognostication for patients receiving first-line immunochemotherapy for follicular lymphoma: a retrospective analysis of a prospective clinical trial and validation in a population-based registry. Lancet Oncol 16, 1111–1122, doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00169-2 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J et al. Both corepressor proteins SMRT and N-CoR exist in large protein complexes containing HDAC3. EMBO J 19, 4342–4350, doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4342 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner FF et al. An Isochemogenic Set of Inhibitors To Define the Therapeutic Potential of Histone Deacetylases in beta-Cell Protection. ACS Chem Biol 11, 363–374, doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00640 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]