Abstract

Since its first description over 30 years ago arthroscopic stabilisation has evolved. With improvements in knowledge, surgical techniques and materials technology, arthroscopic bankart repair has become the most widely used method for treating patients with symptomatic anterior shoulder instability. These procedures are typically performed in a younger, high demand patient population after a primary dislocation or to treat recurrent instability. A thorough clinical evaluation is required in the clinic setting not only to fully understand the injury pattern but also consider patient expectations prior to embarking on surgery. Diagnostic imaging will aid the clinician in determining the soft tissue pathology as well as assessing bone loss, which facilitates surgical decision-making. Selected patients may benefit from adjunctive procedures such as a remplissage for an “engaging” Hill-sachs lesion. This review will focus on the indications, pre-operative considerations, surgical techniques and outcomes of arthroscopic stabilisation.

Keywords: Shoulder instability, Arthroscopic stabilisation, Arthroscopic bankart, Remplissage

1. Introduction

Dislocation of the shoulder may result in a range of pathological lesions involving the soft tissue and bony restraints of the glenohumeral joint. The most common soft tissue lesion is a labral detachment from the glenoid rim (“Bankart” lesion) but it is well recognised that a degree of stretching of the capsular restraints may also occur. Rarely the capsule may be avulsed from its humeral attachment (Humeral avulsion of glenohumeral ligament or “HAGL” lesion). Rotator cuff tears are not uncommon in older individuals with shoulder instability. Bony lesions may include glenoid rim fractures (the “bony Bankart”) and impaction of the humeral head – the Hill-Sachs’ lesion (HSL). Recurrent instability of the shoulder may result from a failure of healing of the initial soft tissue injury, healing of the anterior labroligamentous complex medial to the glenoid rim (“ALPSA” lesion) or as a result of significant bone loss.

Arthroscopic stabilisation or arthroscopic Bankart repair (ABR) of the shoulder is one of a number of options to manage shoulder instability. It offers excellent visualisation of the glenohumeral joint allowing a comprehensive assessment of the pathology and concomitant lesions. Compared to open Bankart repairs (OBR), ABR offers benefits of less postoperative pain and loss of motion and avoids compromising the function of subscapularis1 whilst providing similar reported recurrence and reoperation rates.2 Recent advances in arthroscopic surgical techniques such as incorporation of bony Bankart lesions or Hill-Sachs remplissage (HSR) allow some bony defects to be addressed along with soft tissue lesions. This article will focus on indications, preoperative considerations, the surgical techniques and outcomes of ABR.

2. Indications

ABR may be offered following the first episode of traumatic anterior dislocation in select individuals that are at high risk of recurrence, i.e age <25 years or those participating in contact sports. Arthroscopic stabilisation may be considered for patients with symptomatic recurrent instability of the shoulder, posterior instability, multidirectional instability or activity related pain due to labral tears that has failed to respond to nonsurgical treatment. Arthroscopic stabilisation is particularly advantageous in patients with associated superior extension of the labral tear3,4 or extensive labral tears.5, 6, 7 Patients with minor shoulder instability8 or microinstability9 may have no significant abnormality on imaging and may need to be investigated with arthroscopy, which often reveals subtle labral pathology amenable to arthroscopic repair.

3. Preoperative considerations

3.1. Clinical assessment

A thorough clinical evaluation including a detailed history and focused clinical examination is essential in patients with shoulder instability. The mechanism of initial dislocation may provide clues regarding the direction of instability. Patients with anterior instability will often describe episodes of dislocation or subluxation and it is important to elicit specific details of these events. Patients presenting with multiple dislocations (>5) or episodes occurring with the arm below shoulder height should arouse suspicion of bone loss. Patients with posterior or minor instability often describe symptoms of pain or ‘popping’. Knowledge of the patient's involvement in physical activities and contact sports is crucial when discussing treatment options.

The examination should include assessment of generalised joint laxity in addition to a detailed examination of both shoulders. Some patients may present with isolated signs of shoulder laxity, which include excessive passive external rotation and abduction in the absence of generalised joint laxity. Patients with anterior instability will often demonstrate positive apprehension, relocation and release tests. Apprehension assessment typically includes placing the shoulder in varying degrees of abduction and then bringing the arm into external rotation whilst watching the patient's face for signs of anxiety or apprehension.10 Abolition of the apprehension with a posteriorly directed force on the humeral head denotes a positive “relocation test” and recurrence of anxiety with release of the pressure – a positive “release test”. Posterior instability may manifest with a positive jerk test or Kim's test. The jerk test is performed with the patient in sitting position. With the scapula stabilised the affected arm is held in 90° of abduction and internal rotation and the humerus is axially loaded to force it posteriorly.11 A positive finding is one that provokes pain or a ‘clunk’. Patients with superior labral tears may display positive O'Brien's sign and biceps load tests.

3.2. Investigations

Routine imaging of the shoulder in our practice includes true anteroposterior and axillary lateral radiographs to assess the glenoid rim and Stryker notch views to evaluate HSLs. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the shoulder is considered routinely to detect soft tissue pathology and is particularly useful for detecting Humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) lesions.12 Magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) is still the preferred imaging modality demonstrating higher sensitivity and specificity in identifying labral pathology and assessing capsular volume (Fig. 1).13 However, MRA is not without limitations, a recent study suggesting that MRA may not completely characterise the clinical diagnosis and operative pathology in up to 32% of patients.14 Research is ongoing on the development and implementation of 7-T MR imaging which may potentially reduce the need for invasive diagnostic investigations in the future.15

Fig. 1.

Magnetic Resonance arthrogram of the left shoulder showing a classical Bankart lesion.

Computed Tomography (CT) scans are used selectively in our institution in patients with a history of multiple dislocations (>4), dislocations occurring with minimal force or where plain radiographs suggest significant glenoid rim erosion (Fig. 2). Fine slice CT scans with multi-planar and three-dimensional reformatting are useful in assessing the degree of glenoid bone loss (GBL) (Fig. 3) and the dimensions of the HSL. Although MRI scan can be used to quantify bone loss, CT is still considered the gold standard for assessment of osseous anatomy of the shoulder.16 Multiple methods have been described to measure glenoid bone loss. The senior author uses a multi-planar CT generated ‘en-face’ projection of the glenoid on the sagittal oblique view to calculate linear bone loss of the inferior glenoid.17 Provencher et al. in their review paper recommend the use of a three dimensional CT scan with digital subtraction of the humeral head for accurate quantification of GBL.18 Most techniques utilize the best fit circle as the reference for the calculations which include the Ratio and Pico methods.19,20

Fig. 2.

Plain radiograph showing loss of lower part of the sclerotic line representing the anterior glenoid rim (arrows).

Fig. 3.

Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the left shoulder showing glenoid bone loss at the anterior rim.

3.3. Contraindications

The failure rates following ABR are unacceptably high when there is GBL >25% or there is an engaging HSL involving 30% of the humeral head. These cases should be considered for a ‘bone-block’ procedure, which would give more reliable results. Patient factors are important considerations such as those with collagen disorders and uncontrolled seizure activity. Patients with muscle patterning type instability or those that voluntarily dislocate the shoulder are unlikely to be candidates for initial arthroscopic management.

4. Treatment algorithm

The surgical plan is based on the findings of clinical assessment, imaging, examination under anaesthesia (EUA) and arthroscopic assessment of the joint. Small degrees of GBL (<10%) can usually be managed successfully with ABR. GBL of 10–25% must be considered in conjunction with the size of the associated HSL. “Engaging” HSLs are associated with a high risk of failure of arthroscopic ABR.21

Recently the ‘glenoid track’ concept has been introduced as a way of assessing the risk of a HSL engaging with the glenoid rim22,. The glenoid track is the contact area between the posterior articular margin of the humerus with the glenoid when the arm is in various degrees of abduction, maximum external rotation and horizontal extension23 (Fig. 4). An HSL that lies within the glenoid track is described as “on-track” and may be successfully managed with ABR alone. An HSL that lies outside the glenoid track is described as “off-track” and is associated with increased risk of failure with ABR. Off-track lesions may be addressed by treating the HSL with a remplissage procedure24 or alternatively by increasing the width of the glenoid track with bony reconstruction of the glenoid rim.

Fig. 4.

Glenoid track concept. a. 3d CT image showing the relationship between the glenoid rim defect (dotted line) and the Hill-Sachs lesion (arrows) with the arm in maximal abduction and external rotation. b. En face view of the glenoid showing the anterior glenoid bone loss (dotted line shows the margin of the intact glenoid).c. Posterior view of the humerus depicting the track along which the glenoid (dotted margins) would articulate with the humeral head. In this case the margin of the Hill-Sachs lesion (arrows) lies medial to the glenoid track and would indicate that the lesion is likely to engage in the glenoid defect.

GBL in excess of 25% is a contraindication to an ABR and these patients are better treated with reconstruction of the glenoid rim using either iliac crest bone graft or the Latarjet procedure. Details of these procedures are outside the scope of this article.

5. Surgical technique

The procedure is carried out under general anaesthesia with an interscalene block. An EUA is carried out to confirm the direction in which the shoulder can be translated along with signs of laxity such as the range of passive external rotation in adduction and the Gagey hyperabduction sign. The procedure may be carried out in the lateral decubitus or beach chair position depending on the surgeon's preference. We prefer the lateral decubitus position for reasons discussed later.

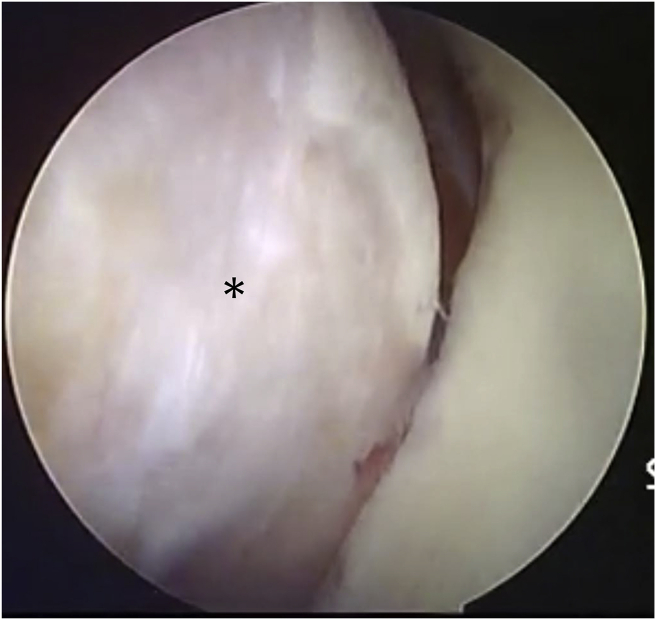

An initial posterior viewing portal is established and a diagnostic arthroscopy is carried out to exclude abnormalities in the rotator cuff or biceps tendon before evaluating the pathology specific to the instability. Whilst anterior labral pathology is usually clearly visible, posterior or superior extensions of the labral tear may be subtle and only apparent on probing. A dynamic assessment of the joint may be carried out by bringing the arm in abduction and external rotation whilst viewing from the posterior portal to assess whether the HSL engages (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Arthroscopic demonstration of an engaging Hill-Sachs lesion(*) in a left shoulder seen from the posterior viewing portal.

We routinely use at least 2 further portals – an anterosuperior portal (ASP) at the anterior edge of the supraspinatus and anterior mid-glenoid portal (AMG) just above the subscapularis. The scope is then switched to the ASP whilst the AMG and posterior portals are used as working portals. Whilst viewing from the ASP, the degree of bone loss on the glenoid and the width of the Hill-Sachs lesion are assessed using a measuring probe from the posterior portal (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Right shoulder seen through anterosuperior viewing portal. Orange hashed line (r) demonstrates anterior radius whilst blue hashed line represents posterior radius (R). Arrow marks bare spot of the glenoid. Glenoid bone loss is estimated by the formula (R-r) x 100/2R.

The glenoid labrum is mobilised from the glenoid rim with an elevator and further medially with a radiofrequency device to minimize bleeding. This is particularly relevant in the case of ALPSA lesions (Fig. 7a). The glenoid rim is freshened with an arthroscopic curette or shaver down to bleeding bone. For the classical anteroinferior labral tear, the repair is carried out with placement of a suture anchor at the 5:30 position using an accessory 5:00 o'clock portal. One strand of suture is shuttled through the inferior labrum using a curved shuttling hook inserted from the posterior portal. The second strand of suture is shuttled around the anteroinferior labrum using a shuttling hook inserted from the AMG. A pinch of the capsule may be taken when passing the shuttling hook to address laxity. In cases where the tear extends posteriorly, additional suture anchors are placed on the posterior glenoid rim starting at the 6:30 position from an accessory posterolateral portal.25 Pairs of inferior sutures are then secured with arthroscopic sliding/locking knots placing the knots on the labral side away from the articular margin. At least 2 further anchors are placed anteriorly below the equator to achieve a secure repair of the anterior labrum (Fig. 7b). Anchor placement is rarely the same for each patient and must be tailored individually depending on the type of tear. We prefer to use knotless anchors with tape in the more proximal locations as they provide secure fixation, avoid potential tissue irritation due to the knots and save time. If torn, the superior labrum can then be repaired in similar fashion by switching the scope to the posterior portal for viewing and using the ASP for anchor placement.

Fig. 7.

a. An ALPSA lesion in a right shoulder as seen from the anterosuperior viewing portal. b. Same shoulder after repair – arrows indicate location of anchors.

The technique may be varied depending on the observed pathology. For instance if there is a less than 25% GBL with a bony fragment attached to the anterior labrum, this can be incorporated in the repair26 (Fig. 8) or repaired with a bridging suture technique.27 In patients with large “off-track” or medially located HSL, a posterior remplissage procedure may be added.24 A decision regarding this is made after the dynamic examination of the joint viewing from the posterior portal and before the labral repair is carried out. In this case, a preliminary bursoscopy to clear the bursal tissue over the infraspinatus may facilitate subsequent retrieval of the sutures and tying of knots. Whilst viewing from the ASP, the HSL is debrided down to bleeding bone and two anchors are placed in the defect through the infraspinatus tendon using an accessory posterior portal prior to repairing the labrum.28,29 Once the labrum is repaired the scope is placed in the subacromial bursa and the sutures for the remplissage are secured with arthroscopic knots (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

a. Right shoulder – bony Bankart lesion as seen from the anterosuperior viewing portal. b. Same shoulder after repair using the technique described by Sugaya (arrows indicate location of anchors).

Fig. 9.

a. Large (engaging) Hill-Sachs lesion in a left shoulder seen from an anterosuperior viewing portal. The needles mark the sites of anchor placement. b. Appearance after remplissage with the infraspinatus (*) attached to the Hill-Sachs lesion. c. Bursal view showing the sutures tied over the infraspinatus tendon (*).

5.1. Postoperative rehabilitation

The arm is immobilised in a sling with an abduction cushion allowing only elbow, wrist and hand movements for the first 3 weeks following the procedure. Thereafter mobilisation of the shoulder is initiated to achieve elevation whilst avoiding positions that may stress the repair for a further 3 weeks. Isometric strengthening is started after 6 weeks and sports specific training after 4 months. Patients are allowed to return to sports at between 6 and 9 months depending on their progress and the type of activity they participate in.

6. Outcomes

Outcomes after arthroscopic stabilisation may be measured in terms of functional gains, rates of recurrence or reoperation, return to sport and complication rates. Excellent functional outcomes have been reported after arthroscopic stabilisation (Table 1). Functional outcomes are correlated to recurrence and unsurprisingly patients with recurrence have worse functional scores.30,31

Table 1.

Overview of literature on outcomes of arthroscopic stabilisation procedures (minimum 20 shoulders).

| Authors | Study type | No of shoulders | Age at surgery (years) | Techniques | Follow up (years) | Redislocation/reoperation rate | Return to sports | Functional outcomes scores | Factors for recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Larrain 2006 (92) |

Case series (Level IV) | 39 acute 121 recurrent Collision athletes |

22 | Fastak suture anchors | 5.9 | 5.1% acute 8.3% recurrent |

100% acute 84.3% recurrent |

Excellent or good in 94.9% of acute and 91.8% recurrent | All recurrences related to repeat trauma playing contact or overhead activity sports |

| Franceschi 2011 (93) |

Case series (Level IV) | 60 | 27.6 | Fastak, Biosuturetak | 8 | 16.6% | 88% | CS – 88 | Half recurrence due to repeat trauma |

| Van der Linde 2011 (37) |

Case series (Level IV) | 68 | 31 | Rodtag with PDS | 8–10 | 35% | NR | OIS-16 WOSI-22 SST- 12 |

Trend with < 2 anchors or a Hill-Sachs (NS) |

| Ahmed 2012 (30) |

Case series (Level IV) | 302 | 26.5 | Suture anchors | 5.8 | 13.2% | NR | WOSI 29.2% deficit DASH 6% deficit (Improved function p < 0.001) |

Patient age Severity of glenoid bone loss Engaging Hil sachs lesions |

| Phadnis 2015 (83) |

Case control series (Level III) | 141 | 27.1 | Bioknotless anchors | 4 | 13.5% | NR | NR | Age < 21; Hill-Sachs; Glenoid bone loss; Elite or Contact sports; ISIS ≥ 4 |

| Szyluk 2015 (35) |

Case series (Level IV) | 92 | 25 | Fastak suture anchors | 8.2 | 10% 6.6% reop |

94.6% full activities | Rowe – 90 UCLA – 33.5 |

All recurrences due to repeat high energy injury |

| Aboalata 2016 (54) | Case series (Level IV) | 143 | 28.17 ± 8.3 | Biosuturetak, Suretac and Panalok anchors | 13 | 18.8% SA – 15.1% ST – 26.3% Panlok – 33% NS |

49.5% same 30.25% reduced |

Satisfaction – 92.3% Rowe – 90 CS – 94 ASES - 92 |

Younger age Rehab < 6 m |

| Milchteim 2016 (94) | Case series (Level IV) | 94 | 21.9 | Biosuturetaks | 5 | 6.4% | 82.5% | ASES – 91.5 Rowe – 84.3 |

High school or recreational athletes at higher risk |

| Flinkilla 2018 (36) |

Case series (Level IV) | 167 | 26 | Suture anchors | 12.2 | 30% 18% reop |

NR | SSV – 84% OSS – 20 WOSI - 80 |

Age < 20 yrs; Time since op |

NR- Not recorded.

CS- Constant Score.

WD-Walch-Duplay.

OSS- Oxford Shoulder Score.

OIS- Oxford Instability Score.

WOSI- Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Score.

ASES- American Shoulder and Elbow Score.

VAS: Visual Analogue Score.

UCLA-University of California at Los Angeles Shoulder Score.

SSV- Subjective Shoulder Value.

6.1. Recurrence rates

OBR32 has traditionally been considered the gold standard in the treatment of shoulder instability but is associated with loss of external rotation32 and this is a major factor contributing to patient dissatisfaction.33 Some of the earlier arthroscopic techniques involving the use of transglenoid sutures or bioresorbable tacks were shown to have inferior functional outcomes and recurrence rates when compared to OBR.34 Arthroscopic techniques have since evolved with suture anchors now being widely used. Individual studies reporting outcomes at 8–12 years after ABR have reported recurrence rates ranging from 10% to 35%.35, 36, 37 A systematic review looking at pooled data demonstrated comparable functional outcomes and recurrence rates for arthroscopic suture anchor repairs and OBRs at 11 years follow-up.38 In a meta-analysis of comparative studies,2 when stratifying publications after 2002, statistically significant lower recurrence rates were reported for arthroscopic repairs (2.9% vs 9.2%). The authors postulated that this may be related to the learning curve required for mastering arthroscopic techniques, better understanding of the disorder and improved patient selection. In a selected cohort of collision athletes excluding those with GBL >25%, large HSLs, gross laxity or HAGL lesions ABR for recurrent instability was associated with a recurrence rate of 8.3% and excellent functional outcomes in over 90%. When judging the success of the procedure based on recurrence rates, it should be noted that recurrence of instability after ABR is often the result of a traumatic event. Furthermore, not all patients who suffer recurrence of instability events after ABR end up having revision surgery.

6.2. Return to sports

The ability to return to sports (RTS) has often been used as a surrogate marker of the success for the surgical treatment for shoulder instability. When assessing RTS after surgical treatment, consideration should be given to subjective and psychosocial factors that may prevent individuals from returning to their previous level of sports despite achieving good to excellent functional outcome scores.39

In a systematic review of 1923 shoulders treated with ABR the pooled rate of RTS to any level was 81%, of which 66% returned to their pre-injury level of sports.40 When considering competitive athletes, 82% returned to their competitive level of sports, and of these 88% returned to their pre-injury level of sports. Equally encouraging results were demonstrated in a systematic review assessing outcomes in athletes after arthroscopic treatment for shoulder instability, with an RTS rate of 97.5% and RTS to pre-injury level of 91.5%.41 The average time to RTS was 5.9 months.

In a case-controlled study comparing the outcomes of ABR and open Bristow-Latarjet procedure, patients undergoing ABR achieved a better result in terms of return to sport.42

6.3. Complications

The overall rate of complications following arthroscopic stabilisation is low. In a systematic review looking at overall complication rates following surgery for anterior glenohumeral dislocations, the incidence of complications was lower for arthroscopic soft tissue repair (1.6%) compared with open soft tissue repair (6.2%).43 The complication rate for open bone block procedures was 7.2% and for arthroscopic bone block procedures 13.6%.

In a survey of a large-scale database of procedures performed by surgeons within the first 5 years of clinical practice, the overall complication rate of ABR was 3.9% compared with a rate of 9.4% after OBR.44 In the same study, the risk of infection after ABR was 0.22%. Amongst a cohort of 4802 patients, the risk of surgical intervention for infection was noted to be 0.04%.45 Superficial portal infections are more common with a reported rate of 1.67%.30 We routinely use prophylactic antibiotics as they have been shown to significantly lower the risk of infection.46

The reported incidence of nerve injury after ABR is 0.3% and compares favourably with an incidence of 2.2% after OBR44 and the 1.8–10% incidence after the Latarjet procedure.47,48 The axillary nerve is at risk as it lies close to the inferior capsule. Surgeons should familiarise themselves with the anatomy of the nerve in this location as it pertains to arthroscopy49 particularly with respect to placement of the 5 o-clock and posterolateral portals.50 The safe margin for arthroscopic placement of sutures around the anteroinferior capsule and labrum is within 1 cm of the glenoid rim.51

Problems related to the use of suture anchors such as pull out, incorrect placement onto the glenoid face and opposite cortex perforation have been reported but can be avoided by correct surgical technique. The overall incidence of hardware failure is less than 1 in 20044. Poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA) anchors have been associated with chondrolysis52 and their use has largely been discontinued. Chondrolysis may occur from inappropriate placement of knots on the articular side of the labrum. The use of intra-articular pain pumps using local anaesthetic particularly Bupivacaine has been associated with chondrolysis and should be avoided.53

Stiffness may occur after any shoulder surgery and ABR is no exception. The incidence of stiffness after ABR is low and usually resolves with physiotherapy.30 The need for further intervention to treat stiffness after ABR is rare.45 Residual loss of external rotation of up to 5° has been reported after ABR.54 However in comparison to open stabilisation procedures range of motion (ROM) restriction is less marked.55, 56, 57 This is most noticeable in external rotation where ROM loss is reportedly greater in open procedures.58,59 Patients also retain better external rotation in the throwing position after ABR compared to patients undergoing the Latarjet procedure.42

7. Risk factors for failure and implications for decision-making

In order to optimise outcomes after arthroscopic stabilisation an understanding of the risk factors leading to failure of treatment or revision surgery is important. These factors may be related to the patient (including patient selection), the patho-anatomy and surgical technique.

7.1. Patient related factors

Younger patients, particularly those under the age of 20 years, appear to be at higher risk of recurrence after arthroscopic stabilisation.32,36,60, 61, 62 It is likely that younger patients are more prone to recurrence of instability after surgery owing to inherent tissue laxity and less developed musculature.

The risk of recurrence after arthroscopic stabilisation increases with the number of prior dislocations.45,63 Furthermore an interval greater than 6 months between the first dislocation and surgery and the total duration for which the shoulder has been dislocated adversely affect outcomes following surgery.64,65 Recurrent dislocations lead to progressive deterioration of the labral-ligamentous complex making the available tissue quality for repair more friable66 and additionally increasing the size of the Hill-Sachs lesion.67 Patients with ALPSA lesions have been observed to report a higher number of dislocations, display a greater degree of bone loss at the glenoid rim and are at increased risk of failure after arthroscopic stabilisation.63,64,68,69

Patients who participate in contact or overhead sports are at greater risk of recurrence44 as are collision athletes.70,71 These factors must be borne in mind when counseling patients about surgical treatment.

7.2. Patho-anatomy

7.2.1. Bone defects

GBL needs to be carefully evaluated in terms of the extent, whether it has resulted from attrition or a rim fracture as well as associated humeral defects (bipolar bone loss). Patients with an “inverted pear” glenoid21 or with an attritional glenoid defect greater than 25%60 suffer unacceptably high rates of recurrence after ABR and should be offered alternative techniques such as the Latarjet72 or bone graft reconstruction of the glenoid rim.73 In contrast to patients with attritional GBL, those with glenoid defects resulting from detached bone fragments appear to fare better with low recurrence rates after ABR where the technique incorporates the bony fragment.26,74,75

In a recent study on ABR in military subjects,31 those with “subcritical” GBL of 13.5% or greater had poor clinical outcomes, despite not having a significantly higher recurrence rate. In a study on collegiate American football players, all patients with GBL >13.5% suffered recurrence of instability after ABR whilst those with <13.5% GBL suffered no recurrence.76 Thus, in higher demand patients with subcritical bone loss, consideration must be given to adjunctive procedures such as remplissage or to alternative procedures such as the Latarjet.

Patients with large, engaging HSL are also at high risk of recurrence after ABR.21 In these patients, application of the glenoid track concept may help in decision-making. Patients with “off-track” HSL have been observed to demonstrate higher recurrence rates77 as well as reoperation rates78 when compared to those with “on-track” lesions. Patients with “off-track” HSL where the GBL is <25% may be managed arthroscopically, however adjunctive treatment such as remplissage may need to be considered.72 The addition of a remplissage prevents the HSL from engaging and thus can reduce recurrence rates (Table 2).24,79,80

Table 2.

Overview of literature on outcomes of arthroscopic Remplissage procedures (minimum 20 shoulders).

| Authors | Study type | No of shoulders | Age at surgery (years) | Follow up (months) | Redislocation/reoperation rate (%) | Return to sports | Functional outcomes scores | Factors for recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yi-Ming Zhu 2011 (95) |

Case Series (Level IV) | 49 | 28.4 (16.7–54.7 | 29 (27–35) | 8.2 | 71.4% Back to pre-operative sports levels | ASES 96 ± 3.4 CM 97.8 ± 3.6 ROWE 89.8 ± 12.5 |

One patient had Repeat trauma and authors speculate poor anterior capsule for repair for other failures |

| Boileau 2012 (96) |

Case series (Level IV) | 47 | 29 ± 5.4 | 24 | 4.25 | 68% same 14% Lower 7% changed sp. 10% no return |

Rowe 91 ± 11 WD 89.5 ± 12 CS 94 ± 7 SSV 58->90% |

Hyperlaxity, Age 18, Competitive basketball player (1 Patient) |

| Merolla 2014 (97) |

Case series (Level IV) | 61 | 28 ± 4.1 | 39.5 (24–56) | 1.6 | 100% | ROWE 96.3 ± 7.9 WD 90.4 ± 7.4 CS 90 ± 5.2 SST 10.4 ± 1 | 1 patient had traumatic dislocation at 34 months post-op |

| Wolf 2014 (24) |

Case Series (Level IV) | 45 | 33 (17–67) | 58 (24–124) | 4.4 | 88.9% | ROWE 92 ± 12 CS 92 ± 10 WOSI 224 ± 261 | 2 patients had repeat trauma |

| Garcia 2016 (98) |

Case Series (Level IV) | 51 | 29.8 (15–72.4) | 60.7 (25–97) | 11.8 | 95.5% 51.7% Throwing |

WOSI 79.5% ASES 89.3 ± 15.2 VAS 0.8 ± 1.9 |

No of pre op dislocations Revision surgery |

| Bonneviale 2017 (99) |

Case Series (Level IV) | 34 | 26 (15–49) | 35(24–63) | 14.8/8.8 | 53% same 8.8% lower |

Rowe 92.7 ± 10.5 WD 88.2 ± 18. |

Depth of HS lesion |

CS- Constant Score.

WD-Walch-Duplay.

OSS- Oxford Shoulder Score.

WOSI- Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Score.

ASES- American Shoulder and Elbow Score.

VAS: Visual Analogue Score.

SST- Simple Shoulder Test.

SSV- Subjective Shoulder Value.

7.2.2. ii) laxity

Patients with ligamentous laxity are at higher risk of recurrence after arthroscopic stabilisation.62,81 A thorough clinical evaluation of the patient in the outpatient clinic and during EUA is vital to assess laxity. Techniques to address the laxity such as plication of the capsule must be considered in the surgical procedure in these patients. Redundancy of the inferior pouch may be treated by performing an inferior and postero-inferior plication beyond the extent of the labral tear.82

The Instability Severity Index score (ISIS) was developed to quantify patient related risk factors and identify those at high risk of failure following ABR.81 It has been independently validated83 and a score of 4 or greater predicts failure of isolated ABR. Thus, in patients with an ISIS score of ≥4, the treatment must include adjunctive or alternative techniques to address bone loss and laxity.

7.3. Technical factors

Patient positioning has been shown to influence outcomes after stabilisation. In a systematic review of 3668 patients, lower recurrence rates were reported for ABR performed in the lateral decubitus position (8.5%) compared to the beach chair position (14.65%).84 The advantages for the lateral position include improved visualisation of the anterior, inferior and posterior glenoid as well as accentuation of the labral tears by the traction provided.

A number of individual studies have investigated the influence of technical factors such as the number of anchors,60 type of anchor85 or whether anchors were knotted or knotless when performing their repairs.86,87 A systematic review looking at these factors found no difference in the risk of recurrent instability following ABR between these variables.88

Positioning of the anchors may also be an influential factor in determining outcome. In a series of 56 arthroscopic revision repairs for recurrent instability89 placement of the initial anchor at the 5:30 position and incorporating the anterior band of the IGHL along with the capsulolabral complex were found to be crucial in preventing anterior instability as the IGHL is believed to be the main restraint for anterior translation in the abduction and external rotation position.85 Accessory portals such as the 5 o'clock and posterolateral portals are invaluable for low anchor placement and to address inferior capsular laxity.

8. Conclusion

Arthroscopic stabilisation has advanced considerably since the first description over 30 years ago.90,91 With improvements in arthroscopic techniques, materials technology and surgical knowledge, ABR has evolved and is the technique of choice for treating anterior shoulder instability without significant bone loss. ABR has a role in patients with moderate degrees of bone loss but requires adjunctive techniques such as incorporation of bony fragments in the repair or the performance of a remplissage. The decision to operate and the choice of surgical technique must be individualised to the patient based on age, sporting aspirations and physical demands. The success rate and functional outcomes of ABR for appropriately selected patients are excellent.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

This researched received no financial grant from any agency in the public, commercial or non-profit sector.

Acknowledgements

None.

Contributor Information

Konstantinos Fountzoulas, Email: kostas.fountzoulas@gmail.com.

Syed Hassan, Email: Syedimon@doctors.org.uk.

Al-achraf Khoriati, Email: alkhoriati@doctors.org.uk.

Chu-Hao Chiang, Email: cchiangmd@gmail.com.

Nicholas Little, Email: nick.little@nhs.net.

Vipul Patel, Email: Vipul.Patel4@nhs.net.

References

- 1.Scheibel M., Nikulka C., Dick A., Schroeder R.J., Popp A.G., Haas N.P. Structural integrity and clinical function of the subscapularis musculotendinous unit after arthroscopic and open shoulder stabilization. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1153–1161. doi: 10.1177/0363546507299446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrera M., Patella V., Patella S., Theodoropoulos J. A meta-analysis of open versus arthroscopic Bankart repair using suture anchors. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(12):1742–1747. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carreira D.S., Mazzocca A.D., Oryhon J., Brown F.M., Hayden J.K., Romeo A.A. A prospective outcome evaluation of arthroscopic Bankart repairs: minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(5):771–777. doi: 10.1177/0363546505283259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hantes M.E., Venouziou A.I., Liantsis A.K., Dailiana Z.H., Malizos K.N. Arthroscopic repair for chronic anterior shoulder instability: a comparative study between patients with Bankart lesions and patients with combined Bankart and superior labral anterior posterior lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(6):1093–1098. doi: 10.1177/0363546508331139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricchetti E.T., Ciccotti M.C., O'Brien D.F. Outcomes of arthroscopic repair of panlabral tears of the glenohumeral joint. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(11):2561–2568. doi: 10.1177/0363546512460834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tokish L.J.M., McBratney M.C.M., Solomon C.D.J., LeClere L.L., Dewing L.C.B., Provencher C.M.T. Arthroscopic repair of circumferential lesions of the glenoid labrum: surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(Suppl 1):130–144. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alpert J.M., Verma N., Wysocki R., Yanke A.B., Romeo A.A. Arthroscopic treatment of multidirectional shoulder instability with minimum 270 degrees labral repair: minimum 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(6):704–711. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castagna A., Nordenson U., Garofalo R., Karlsson J. Minor shoulder instability. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(2):211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chambers L., Altchek D.W. Microinstability and internal impingement in overhead athletes. Clin Sports Med. 2013;32(4):697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine W.N., Sonnenfeld J.J., Shiu B. Shoulder instability. Clin Sports Med. 2018;37(2):161–177. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim S.-H., Park J.-C., Park J.-S., Oh I. Painful jerk test: a predictor of success in nonoperative treatment of posteroinferior instability of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(8):1849–1855. doi: 10.1177/0363546504265263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knapik D.M., Voos J.E. Magnetic resonance imaging and arthroscopic correlation in shoulder instability. Sport Med Arthrosc Rev. 2017;25(4):172–178. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magee T. 3-T MRI of the shoulder: is MR arthrography necessary? Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(1):86–92. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song D.J., Cook J.B., Krul K.P. High frequency of posterior and combined shoulder instability in young active patients. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2015;24(2):186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alizai H., Chang G., Regatte R.R. MR imaging of the musculoskeletal system using ultrahigh field (7T) MR imaging. Pet Clin. 2018;13(4):551–565. doi: 10.1016/j.cpet.2018.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon Y.W., Powell K.A., Yum J.K., Brems J.J., Iannotti J.P. Use of three-dimensional computed tomography for the analysis of the glenoid anatomy. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2005;14(1):85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabinowitz J., Friedman R., Eichinger J.K. Management of glenoid bone loss with anterior shoulder instability: indications and outcomes. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10(4):452–462. doi: 10.1007/s12178-017-9439-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Provencher C.M.T., Bhatia S., Ghodadra N.S. Recurrent shoulder instability: current concepts for evaluation and management of glenoid bone loss. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(Suppl 2):133–151. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barchilon V.S., Kotz E., Barchilon Ben-Av M., Glazer E., Nyska M. A simple method for quantitative evaluation of the missing area of the anterior glenoid in anterior instability of the glenohumeral joint. Skelet Radiol. 2008;37(8):731–736. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baudi P., Righi P., Bolognesi D. How to identify and calculate glenoid bone deficit. Chir Organi Mov. 2005;90(2):145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burkhart S.S., De Beer J.F. Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs: significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(7):677–694. doi: 10.1053/jars.2000.17715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto N., Itoi E., Abe H. Contact between the glenoid and the humeral head in abduction, external rotation, and horizontal extension: a new concept of glenoid track. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2007;16(5):649–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itoi E. “On-track” and “off-track” shoulder lesions. EFORT Open Rev. 2017;2(8):343–351. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.2.170007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolf E.M., Arianjam A. Hill-Sachs remplissage, an arthroscopic solution for the engaging Hill-Sachs lesion: 2- to 10-year follow-up and incidence of recurrence. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2014;23(6):814–820. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seroyer S.T., Nho S.J., Provencher M.T., Romeo A.A. Four-quadrant approach to capsulolabral repair: an arthroscopic road map to the glenoid. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(4):555–562. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugaya H., Moriishi J., Kanisawa I., Tsuchiya A. Arthroscopic osseous Bankart repair for chronic recurrent traumatic anterior glenohumeral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(8):1752–1760. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millett P.J., Braun S. The “bony Bankart bridge” procedure: a new arthroscopic technique for reduction and internal fixation of a bony Bankart lesion. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(1):102–105. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koo S.S., Burkhart S.S., Ochoa E. Arthroscopic double-pulley remplissage technique for engaging Hill-Sachs lesions in anterior shoulder instability repairs. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(11):1343–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexander T.C., Beicker C., Tokish J.M. Arthroscopic remplissage for moderate-size hill-sachs lesion. Arthrosc Technol. 2016;5(5):e975–e979. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed I., Ashton F., Robinson C.M. Arthroscopic Bankart repair and capsular shift for recurrent anterior shoulder instability: functional outcomes and identification of risk factors for recurrence. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(14):1308–1315. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaha J.S., Cook J.B., Song D.J. Redefining “critical” bone loss in shoulder instability: functional outcomes worsen with “subcritical” bone loss. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1719–1725. doi: 10.1177/0363546515578250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rowe C.R., Patel D., Southmayd W.W. The Bankart procedure: a long-term end-result study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(1):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahme H., Vikerfors O., Ludvigsson L., Elvèn M., Michaëlsson K. Loss of external rotation after open Bankart repair: an important prognostic factor for patient satisfaction. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(3):404–408. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0987-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freedman K.B., Smith A.P., Romeo A.A., Cole B.J., Bach B.R. Open Bankart repair versus arthroscopic repair with transglenoid sutures or bioabsorbable tacks for Recurrent Anterior instability of the shoulder: a meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(6):1520–1527. doi: 10.1177/0363546504265188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szyluk K., Jasiński A., Widuchowski W., Mielnik M., Koczy B. Results of arthroscopic bankart lesion repair in patients with post-traumatic anterior instability of the shoulder and a non-engaging hill-sachs lesion with a suture anchor after a minimum of 6-year follow-up. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:2331–2338. doi: 10.12659/MSM.894387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flinkkilä T., Knape R., Sirniö K., Ohtonen P., Leppilahti J. Long-term results of arthroscopic Bankart repair: minimum 10 years of follow-up. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(1):94–99. doi: 10.1007/s00167-017-4504-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Linde J.A., van Kampen D.A., Terwee C.B., Dijksman L.M., Kleinjan G., Willems W.J. Long-term results after arthroscopic shoulder stabilization using suture anchors: an 8- to 10-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(11):2396–2403. doi: 10.1177/0363546511415657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris J.D., Gupta A.K., Mall N.A. Long-term outcomes after Bankart shoulder stabilization. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(5):920–933. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tjong V.K., Devitt B.M., Murnaghan M.L., Ogilvie-Harris D.J., Theodoropoulos J.S. A qualitative investigation of return to sport after arthroscopic bankart repair: beyond stability. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(8):2005–2011. doi: 10.1177/0363546515590222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Memon M., Kay J., Cadet E.R., Shahsavar S., Simunovic N., Ayeni O.R. Return to sport following arthroscopic Bankart repair: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2018;27(7):1342–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdul-Rassoul H., Galvin J.W., Curry E.J., Simon J., Li X. Return to sport after surgical treatment for anterior shoulder instability: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. June 2018 doi: 10.1177/0363546518780934. 363546518780934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blonna D., Bellato E., Caranzano F., Assom M., Rossi R., Castoldi F. Arthroscopic bankart repair versus open bristow-latarjet for shoulder instability: a matched-pair multicenter study focused on return to sport. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(12):3198–3205. doi: 10.1177/0363546516658037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams H.L.M., Evans J.P., Furness N.D., Smith C.D. It's not all about redislocation: a systematic review of complications after anterior shoulder stabilization surgery. Am J Sports Med. December 2018 doi: 10.1177/0363546518810711. 363546518810711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Owens B.D., Harrast J.J., Hurwitz S.R., Thompson T.L., Wolf J.M. Surgical trends in bankart repair: an analysis of data from the American board of orthopaedic surgery certification examination. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(9):1865–1869. doi: 10.1177/0363546511406869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wasserstein D.N., Sheth U., Colbenson K. The true recurrence rate and factors predicting recurrent instability after nonsurgical management of traumatic primary anterior shoulder dislocation: a systematic review. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2016;32(12):2616–2625. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Randelli P., Castagna A., Cabitza F., Cabitza P., Arrigoni P., Denti M. Infectious and thromboembolic complications of arthroscopic shoulder surgery. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2010;19(1):97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shah A.A., Butler R.B., Romanowski J., Goel D., Karadagli D., Warner J.J.P. Short-term complications of the Latarjet procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(6):495–501. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Griesser M.J., Harris J.D., McCoy B.W. Complications and re-operations after Bristow-Latarjet shoulder stabilization: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2013;22(2):286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Price M.R., Tillett E.D., Acland R.D., Nettleton G.S. Determining the relationship of the axillary nerve to the shoulder joint capsule from an arthroscopic perspective. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(10):2135–2142. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200410000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhatia D.N., de Beer J.F., Dutoit D.F. An anatomic study of inferior glenohumeral recess portals: comparative anatomy at risk. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(5):506–513. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eakin C.L., Dvirnak P., Miller C.M., Hawkins R.J. The relationship of the axillary nerve to arthroscopically placed capsulolabral sutures. An anatomic study. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(4):505–509. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260040501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCarty L.P., Buss D.D., Datta M.W., Freehill M.Q., Giveans M.R. Complications observed following labral or rotator cuff repair with use of poly-L-lactic acid implants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(6):507–511. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsen F.A., Papadonikolakis A. Published evidence demonstrating the causation of glenohumeral chondrolysis by postoperative infusion of local anesthetic via a pain pump. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(12):1126–1134. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aboalata M., Plath J.E., Seppel G., Juretzko J., Vogt S., Imhoff A.B. Results of arthroscopic bankart repair for anterior-inferior shoulder instability at 13-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(4):782–787. doi: 10.1177/0363546516675145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huerta A., Rincón G., Peidro L., Combalia A., Sastre S. Controversies in the surgical management of shoulder instability: open vs arthroscopic procedures. Open Orthop J. 2017;11(1):875–881. doi: 10.2174/1874325001711010875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hohmann E., Tetsworth K., Glatt V. Open versus arthroscopic surgical treatment for anterior shoulder dislocation: a comparative systematic review and meta-analysis over the past 20 years. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2017;26(10):1873–1880. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen L., Xu Z., Peng J., Xing F., Wang H., Xiang Z. Effectiveness and safety of arthroscopic versus open Bankart repair for recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation: a meta-analysis of clinical trial data. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135(4):529–538. doi: 10.1007/s00402-015-2175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fabbriciani C., Milano G., Demontis A., Fadda S., Ziranu F., Mulas P.D. Arthroscopic versus open treatment of Bankart lesion of the shoulder: a prospective randomized study. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(5):456–462. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jørgensen U., Svend-Hansen H., Bak K., Pedersen I. Recurrent post-traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation - open versus arthroscopic repair. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 1999;7(2):118–124. doi: 10.1007/s001670050133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boileau P., Villalba M., Héry J.-Y., Balg F., Ahrens P., Neyton L. Risk factors for recurrence of shoulder instability after arthroscopic Bankart repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1755–1763. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Porcellini G., Campi F., Pegreffi F., Castagna A., Paladini P. Predisposing factors for recurrent shoulder dislocation after arthroscopic treatment. J Bone Jt Surg. 2009;91(11):2537–2542. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Voos J.E., Livermore R.W., Feeley B.T. Prospective evaluation of arthroscopic bankart repairs for anterior instability. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(2):302–307. doi: 10.1177/0363546509348049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gasparini G., De Benedetto M., Cundari A. Predictors of functional outcomes and recurrent shoulder instability after arthroscopic anterior stabilization. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(2):406–413. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3785-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Porcellini G., Paladini P., Campi F., Paganelli M. Long-term outcome of acute versus chronic bony Bankart lesions managed arthroscopically. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(12):2067–2072. doi: 10.1177/0363546507305011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Denard P.J., Dai X., Burkhart S.S. Increasing preoperative dislocations and total time of dislocation affect surgical management of anterior shoulder instability. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2015;9(1):1–5. doi: 10.4103/0973-6042.150215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Habermeyer P., Gleyze P., Rickert M. Evolution of lesions of the labrum-ligament complex in posttraumatic anterior shoulder instability: a prospective study. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1999;8(1):66–74. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(99)90058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spatschil A., Landsiedl F., Anderl W. Posttraumatic anterior-inferior instability of the shoulder: arthroscopic findings and clinical correlations. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006;126(4):217–222. doi: 10.1007/s00402-005-0006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bernhardson A.S., Bailey J.R., Solomon D.J., Stanley M., Provencher M.T. Glenoid bone loss in the setting of an anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion tear. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(9):2136–2140. doi: 10.1177/0363546514539912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ozbaydar M., Elhassan B., Diller D., Massimini D., Higgins L.D., Warner J.J.P. Results of arthroscopic capsulolabral repair: bankart lesion versus anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion lesion. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(11):1277–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Calvo E., Granizo J.J., Fernández-Yruegas D. Criteria for arthroscopic treatment of anterior instability of the shoulder: a prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(5):677–683. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B5.15794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alkaduhimi H., van der Linde J.A., Willigenburg N.W., Paulino Pereira N.R., van Deurzen D.F.P., van den Bekerom M.P.J. Redislocation risk after an arthroscopic Bankart procedure in collision athletes: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2016;25(9):1549–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Di Giacomo G., Itoi E., Burkhart S.S. Evolving concept of bipolar bone loss and the Hill-Sachs lesion: from “engaging/non-engaging” lesion to “on-track/off-track” lesion. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(1):90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Steffen V., Hertel R. Rim reconstruction with autogenous iliac crest for anterior glenoid deficiency: forty-three instability cases followed for 5-19 years. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2013;22(4):550–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mologne T.S., Provencher M.T., Menzel K.A., Vachon T.A., Dewing C.B. Arthroscopic stabilization in patients with an inverted pear glenoid: results in patients with bone loss of the anterior glenoid. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(8):1276–1283. doi: 10.1177/0363546507300262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kitayama S., Sugaya H., Takahashi N. Clinical outcome and glenoid morphology after arthroscopic repair of chronic osseous bankart lesions: a five to eight-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(22):1833–1843. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dickens J.F., Owens B.D., Cameron K.L. The effect of subcritical bone loss and exposure on recurrent instability after arthroscopic bankart repair in intercollegiate American football. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(8):1769–1775. doi: 10.1177/0363546517704184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shaha J.S., Cook J.B., Rowles D.J., Bottoni C.R., Shaha S.H., Tokish J.M. Clinical validation of the glenoid track concept in anterior glenohumeral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(22):1918–1923. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.01099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Locher J., Wilken F., Beitzel K. Hill-sachs off-track lesions as risk factor for recurrence of instability after arthroscopic bankart repair. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(10):1993–1999. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Buza J.A., Iyengar J.J., Anakwenze O.A., Ahmad C.S., Levine W.N. Arthroscopic hill-sachs remplissage: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(7):549–555. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rashid M.S., Crichton J., Butt U., Akimau P.I., Charalambous C.P. Arthroscopic “Remplissage” for shoulder instability: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(2):578–584. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-2881-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Balg F., Boileau P. The instability severity index score. A simple pre-operative score to select patients for arthroscopic or open shoulder stabilisation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(11):1470–1477. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B11.18962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shin J.J., Mascarenhas R., Patel A.V. Clinical outcomes following revision anterior shoulder arthroscopic capsulolabral stabilization. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135(11):1553–1559. doi: 10.1007/s00402-015-2294-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Phadnis J., Arnold C., Elmorsy A., Flannery M. Utility of the instability severity index score in predicting failure after arthroscopic anterior stabilization of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(8):1983–1988. doi: 10.1177/0363546515587083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Frank R.M., Saccomanno M.F., McDonald L.S., Moric M., Romeo A.A., Provencher M.T. Outcomes of arthroscopic anterior shoulder instability in the beach chair versus lateral decubitus position: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(10):1349–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Imhoff A.B., Ansah P., Tischer T. Arthroscopic repair of anterior-inferior glenohumeral instability using a portal at the 5:30-o’clock position: analysis of the effects of age, fixation method, and concomitant shoulder injury on surgical outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(9):1795–1803. doi: 10.1177/0363546510370199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nho S.J., Frank R.M., Van Thiel G.S. A biomechanical analysis of anterior Bankart repair using suture anchors. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(7):1405–1412. doi: 10.1177/0363546509359069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ranawat A.S., Golish S.R., Miller M.D. Modes of failure of knotted and knotless suture anchors in an arthroscopic bankart repair model with the capsulolabral tissues intact. Am J Orthoped. 2011;40(3):134–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Brown L., Rothermel S., Joshi R., Dhawan A. Recurrent instability after arthroscopic bankart reconstruction: a systematic review of surgical technical factors. Arthroscopy. 2017;33(11):2081–2092. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bartl C., Schumann K., Paul J., Vogt S., Imhoff A.B. Arthroscopic capsulolabral revision repair for recurrent anterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(3):511–518. doi: 10.1177/0363546510388909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Morgan C.D., Bodenstab A.B. Arthroscopic Bankart suture repair: technique and early results. Arthroscopy. 1987;3(2):111–122. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(87)80027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Akad A.M.E., Winge S., Molinari M., Eriksson E. Arthroscopic Bankart procedures for anterior shoulder instability: a review of the literature. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 1993;1(2):113–122. doi: 10.1007/BF01565465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Larrain M.V., Montenegro H.J., Mauas D.M., Collazo C.C., Pavón F. Arthroscopic management of traumatic anterior shoulder instability in collision athletes: analysis of 204 cases with a 4- to 9-year follow-up and results with the suture anchor technique. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(12):1283–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Franceschi F., Papalia R., Del Buono A., Vasta S., Maffulli N., Denaro V. Glenohumeral osteoarthritis after arthroscopic Bankart repair for anterior instability. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(8):1653–1659. doi: 10.1177/0363546511404207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Milchteim C., Tucker S.A., Nye D.D. Outcomes of bankart repairs using modern arthroscopic technique in an athletic population. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2016;32(7):1263–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhu Y.-M., Lu Y., Zhang J., Shen J.-W., Jiang C.-Y. Arthroscopic Bankart repair combined with remplissage technique for the treatment of anterior shoulder instability with engaging Hill-Sachs lesion: a report of 49 cases with a minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(8):1640–1647. doi: 10.1177/0363546511400018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Boileau P., O'Shea K., Vargas P., Pinedo M., Old J., Zumstein M. Anatomical and functional results after arthroscopic Hill-Sachs remplissage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(7):618–626. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Merolla G., Paladini P., Di Napoli G., Campi F., Porcellini G. Outcomes of arthroscopic hill-sachs remplissage and anterior bankart repair: a retrospective controlled study including ultrasound evaluation of posterior capsulotenodesis and infraspinatus strength assessment. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(2):407–414. doi: 10.1177/0363546514559706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Garcia G.H., Wu H.-H., Liu J.N., Huffman G.R., Kelly J.D. Outcomes of the remplissage procedure and its effects on return to sports: average 5-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(5):1124–1130. doi: 10.1177/0363546515626199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bonnevialle N., Azoulay V., Faraud A., Elia F., Swider P., Mansat P. Results of arthroscopic Bankart repair with Hill-Sachs remplissage for anterior shoulder instability. Int Orthop. 2017;41(12):2573–2580. doi: 10.1007/s00264-017-3491-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]