Significance

Hepsin is a cell membrane-bound enzyme discovered in the human liver. To date, the function of hepsin in the body remains unclear. Here we show that hepsin increases glycogen and lipid production in the liver and lowers metabolic rates and adipose tissue browning in mice. This function is medicated by the activation of hepatocyte growth factor and downstream Met signaling in both hepatocytes and adipocytes. Hepsin-deficient mice are resistant to obesity, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia caused by a high-fat diet or leptin receptor deficiency. Our findings identify hepsin as a key regulator in the liver and energy metabolism, suggesting that hepsin may be a novel therapeutic target for obesity, dyslipidemia, and diabetes.

Keywords: adipocytes, hepatocytes, hepatocyte growth factor, hepsin

Abstract

Hepsin is a transmembrane serine protease primarily expressed in the liver. To date, the physiological function of hepsin remains poorly defined. Here we report that hepsin-deficient mice have low levels of blood glucose and lipids and liver glycogen, but increased adipose tissue browning and basal metabolic rates. The phenotype is caused by reduced hepatocyte growth factor activation and impaired Met signaling, resulting in decreased liver glucose and lipid metabolism and enhanced adipocyte browning. Hepsin-deficient mice exhibit marked resistance to high-fat diet-induced obesity, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia. In db/db mice, hepsin deficiency ameliorates obesity and diabetes. These data indicate that hepsin is a key regulator in liver metabolism and energy homeostasis, suggesting that hepsin could be a therapeutic target for treating obesity and diabetes.

The liver is a major organ in metabolic homeostasis. Liver dysfunction is associated with common metabolic diseases such as obesity and type II diabetes that are major risk factors for leading health problems including stroke, myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease (1–5). Hepsin is a serine protease discovered in human hepatocytes (6). It consists of an N-terminal cytoplasmic tail, a single-spanning transmembrane domain, and an extracellular region with a scavenger receptor-like domain and a C-terminal serine protease domain of the trypsin fold (7). Such an overall structural arrangement is similar to those in other type II transmembrane serine proteases (8, 9), which function in diverse tissues to regulate physiological homeostasis, ranging from food digestion to salt–water balance to epithelial integrity to iron metabolism to vascular remodeling (10–15).

Hepsin is expressed predominantly in the liver (6, 16). To date, its physiological function remains unclear. Previous studies suggest that hepsin may play a role in the regulation of hepatocyte growth and morphology (17, 18). In mice, however, hepsin is dispensable for embryonic development, postnatal survival, and liver regeneration (19, 20). In addition to the liver, hepsin is expressed, at lower levels, in the kidney and inner ears, where hepsin is implicated in uromodulin processing and auditory nerve development, respectively (21–23). Moreover, hepsin up-regulation has been found in many human cancers, including prostate, kidney, breast, and ovarian cancers (15, 24), suggesting a role of hepsin in promoting tumor invasion and metastasis.

Given the importance of the liver in metabolic homeostasis and the fact that hepsin is most abundantly expressed in the liver, we hypothesize that hepsin may have a regulatory function in liver and energy metabolism. In this study, we tested this hypothesis by analyzing hepsin-deficient (Hpn−/−) mice. Our results show that hepsin plays an important role in promoting liver metabolism and inhibiting adipocyte browning in a hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and Met signaling-mediated mechanism.

Results

Hpn−/− Mice Have Decreased Levels of Blood Glucose and Lipids and Liver Glycogen.

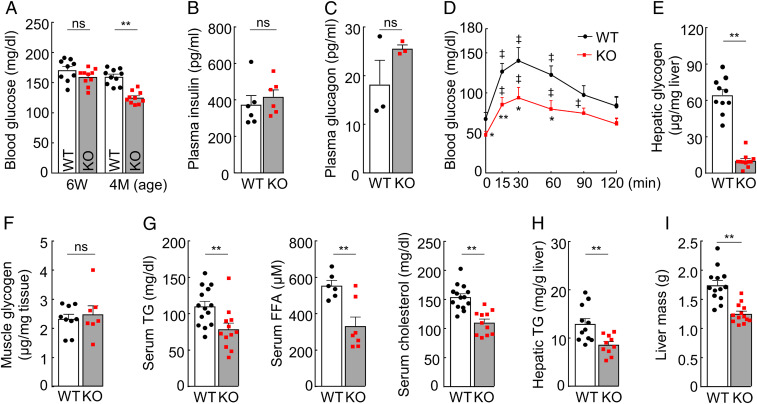

To examine the function of hepsin, we measured blood glucose in Hpn−/− and wild-type (WT) mice. At 6 wk of age, Hpn−/− and WT mice had similar blood glucose levels (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). At 4 mo of age or older, blood glucose levels in Hpn−/− mice decreased (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). There were, however, no apparent differences in plasma insulin and glucagon levels between Hpn−/− and WT mice (Fig. 1 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B and C). In glucose and insulin tolerance tests, Hpn−/− mice responded to glucose and insulin challenges, although their blood glucose levels were consistently lower than those in WT mice, making Hpn−/− mice more susceptible to insulin-induced hypoglycemia (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 D and E). Moreover, Hpn−/− mice had reduced glycogen levels in the liver (measured at 3 wk and 4 mo of age; Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 F and G), but not in skeletal muscles (Fig. 1F and SI Appendix, Fig. S1H), and had reduced levels of serum triglyceride, free fatty acid (FFA), and cholesterols (Fig. 1G and SI Appendix, Fig. S1I). Hepatic triglyceride levels and liver mass were lower in Hpn−/− males (Fig. 1 H and I), but not Hpn−/− females, whereas hepatic FFA and cholesterol levels were similar between Hpn−/− and WT mice. These results suggest a role of hepsin in promoting liver glucose and lipid metabolism.

Fig. 1.

Levels of blood glucose, liver glycogen, serum lipids, and liver triglyceride and mass. (A) Nonfasting blood glucose levels in male WT and Hpn−/− (KO) mice at indicated ages (n = 9–10). (B and C) Plasma levels of insulin (n = 6; B) and glucagon (n = 3; C) in 12-wk-old male mice. (D) Glucose tolerance test in 14-wk-old male mice (ǂP < 0.01 vs. time 0 of the same genotype; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. WT; n = 7–9). (E) Hepatic glycogen levels in 4-mo-old male mice (n = 10–11). (F) Muscle glycogen levels in 4-mo-old male mice (n = 7–9). (G) Serum triglyceride (TG; n = 12–14), free fatty acid (FFA; n = 6–7), and total cholesterol (n = 11–14) levels in 4-mo-old male mice. (H) Hepatic TG levels in 4-mo-old male mice (n = 10–11). (I) Liver mass in 6-mo-old male mice (n = 13). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). ns, not significant.

Hpn−/− Mice Have Increased Metabolic Rates.

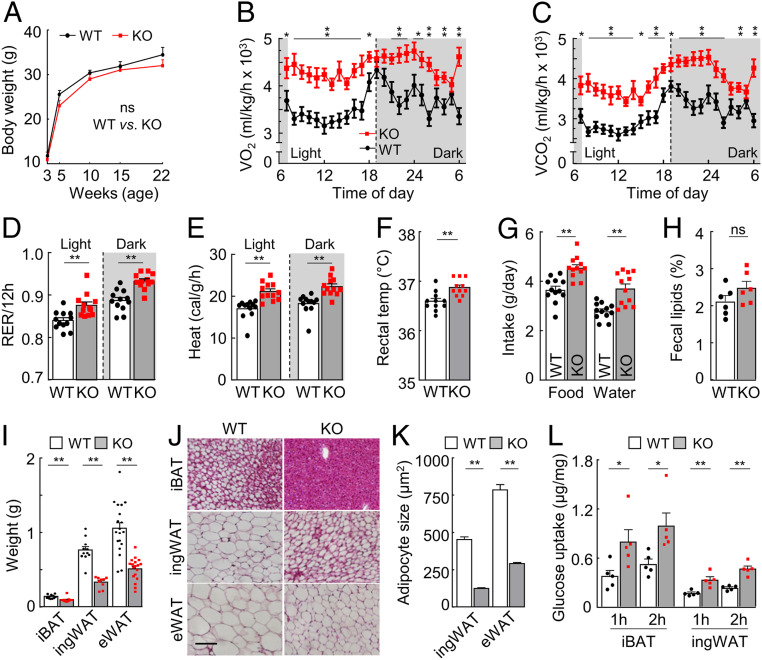

Hpn−/− and WT mice had similar body weights (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). In metabolic studies, Hpn−/− mice had increased O2 consumption, CO2 production, respiratory exchange ratio, heat generation, and core body temperature compared to those in WT mice (Fig. 2B–F and SI Appendix, Fig. S2B), although their motor activities were similar to those in WT mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 C and D). Food and water intakes were also higher in Hpn−/− mice (Fig. 2G and SI Appendix, Fig. S2E), whereas fecal lipid levels were similar between Hpn−/− and WT mice (Fig. 2H and SI Appendix, Fig. S2F). Increased energy expenditures often are associated with changes in adipose tissues. Indeed, Hpn−/− mice had reduced adipose weights and smaller adipocyte sizes in all fat deposits examined (Fig. 2 I–K and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and B). When assayed in culture with insulin, interscapular brown adipose tissues (iBATs) and inguinal white adipose tissues (ingWATs) from Hpn−/− mice had approximately twofold increases in glucose uptake compared to those in WT controls (Fig. 2L). These results indicate that hepsin deficiency increases metabolic rates and decreases adiposity in mice.

Fig. 2.

Metabolic rates, adipose tissue weights, and adipocyte sizes. (A) Body weights in 3–22-wk-old male WT and Hpn−/− (KO) mice (n = 6). (B–F) O2 consumption (VO2; B), CO2 production (VCO2; C), respiratory exchange ratio (RER; D), heat generation (E), and rectal temperature (temp; F) in 4–5-mo-old male mice on a chow diet in light and dark cycles (n = 10–12). (G and H) Food and water (G) intakes and percentages of fecal lipids (H) in 4–5-mo-old male mice (n = 6–12). (I–K) Adipose tissue weights (I) and adipocyte morphology (J) and sizes (K) of interscapular brown adipose tissue (iBAT), inguinal white adipose tissue (ingWAT), and epididymal (“E”) WAT from 27-wk-old male mice. In I, n > 9. (Scale bar: J, 50 μm.) In K, sizes of ≥100 adipocytes in randomly selected fields were measured by imaging software in H&E-stained ingWAT and eWAT sections. (L) Glucose uptakes by iBAT and ingWAT from fasted 4–5-mo-old male mice, assayed after 1 and 2 h (H) of incubation in vitro (n = 5). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). ns, not significant.

Hpn−/− Mice Have Impaired HGF Activation and Met Signaling in the Liver.

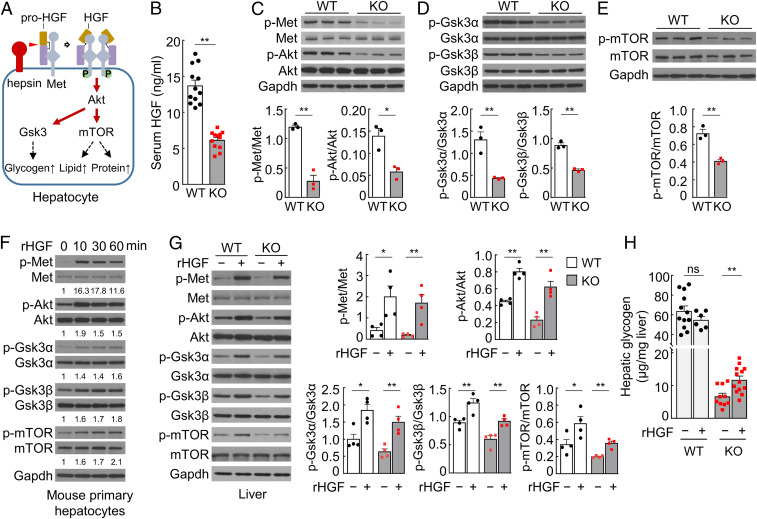

We investigated the mechanism underlying the phenotype in Hpn−/− mice. As a protease, hepsin was shown to cleave several protein substrates in vitro (24–26). The physiological significance of such activities, however, remains unclear. We and others reported that hepsin converted pro-HGF to HGF (25–27), a potent ligand for Met (28, 29). It has been shown that pro-HGF binds to but does not activate Met (30, 31). Subsequent proteolytic conversion of pro-HGF to two-chain HGF triggers Met activation and signaling (31, 32). Hpn (encoding hepsin), Hgf (encoding pro-HGF), and Met genes are all expressed in the liver. Possibly, the membrane-anchored hepsin activates Met-bound pro-HGF, thereby promoting Met signaling and liver metabolism (Fig. 3A). In supporting this hypothesis, Hpn−/− mice had reduced serum HGF levels, as analyzed by ELISA and Western blotting (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–C). In the liver, Hgf mRNA levels were comparable in Hpn−/− and WT mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D), whereas pro-HGF protein levels were higher in Hpn−/− mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S4E), indicating that pro-HGF conversion to HGF, but not Hgf expression, is impaired in Hpn−/− mice.

Fig. 3.

Pro-HGF activation and Met signaling in livers and cultured hepatocytes. (A) A proposed model. Hepsin activates Met-bound pro-HGF on the cell surface, allowing HGF β-chain (brown) binding to Met and causing Met phosphorylation (“P”) and dimerization. Met signaling activates downstream Akt, Gsk3, and mTOR, promoting glycogen, lipid, and protein synthesis in hepatocytes. (B) Serum HGF levels in 4-mo-old male mice by ELISA (n = 11–12). (C–E) Western blotting of Met, Akt (C), Gsk3α/β (D), and mTOR (E) phosphorylation in livers from 6-mo-old male mice. Phosphorylated vs. unphosphorylated protein ratios were analyzed by densitometry (n = 3). (F) Western blotting of Met, Akt, Gsk3α/β, and mTOR phosphorylation in mouse primary hepatocytes cultured with rHGF (20 ng/mL). Numbers below Western blots are fold changes of phosphorylated protein levels vs. corresponding controls at time 0. (G) Western blotting of Met, Akt, Gsk3α/β, and mTOR phosphorylation in livers from 5–6-mo-old male mice with i.v. injection of rHGF (+) or buffer (−). Phosphorylated vs. unphosphorylated protein ratios were calculated by densitometry (n = 4). The other three sets of Western blots are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S5F. (H) Liver glycogen levels in 5–6-mo-old male mice with i.v. injection of rHGF (+) or buffer (−; n = 6–13). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). ns, not significant.

By Western blotting, we found decreased Met and Akt phosphorylation in Hpn−/− livers (Fig. 3C), an indication of reduced Met activation and signaling. Reduced phosphorylation also was observed in Gsk3α/β that are Akt downstream effectors (Fig. 3D). Phosphorylation of Gsk3 prevents the inhibition of glycogen synthase and thus increases glycogen synthesis. Conversely, reduced Gsk3 phosphorylation decreases glycogen synthesis, consistent with the reduced blood glucose and hepatic glycogen levels in Hpn−/− mice. These data support a role of hepsin in HGF activation and Met signaling, thereby promoting liver glycogen synthesis.

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is another AKT effector that promotes lipid and protein synthesis (29, 33, 34). In Western blotting, mTOR phosphorylation decreased in Hpn−/− livers (Fig. 3E). Moreover, reduced levels of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (Ppar-γ) and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (Srebp-1), two mTOR downstream effectors, also were observed (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B). In qRT-PCR, Srebp-1 downstream genes in glycolysis and lipid synthesis, including glucose transport 2 (Glut2), glycerol kinase (Gk), pyruvate kinase (Pklr), ATP citrate lyase (Acly), acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha (Acaca), fatty acid synthase (Fasn), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (Scd1), were all down-regulated in Hpn−/− livers (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C). These results are consistent with the reduced serum triglyceride levels in Hpn−/− mice, supporting a role of hepsin in promoting liver lipid mechanism. The liver is a primary producer for plasma proteins. Given the role of mTOR in protein synthesis, reduced Met-Akt-mTOR signaling is expected to decrease protein synthesis in the liver. Indeed, total serum protein levels in Hpn−/− mice (72.26 ± 0.89 mg/mL) were ∼22% lower than in WT mice (92.04 ± 2.27 mg/mL; n = 6; P < 0.001).

To verify these results, we cultured hepatocytes with recombinant (r) HGF and examined Met activation and signaling. Western blotting showed increased Met, Akt, Gsk3α/β, and mTOR phosphorylation in rHGF-treated mouse primary hepatocytes (Fig. 3F) and human hepatoma HepG2 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). In both of the cell types, glycogen levels were increased upon rHGF stimulation (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 B–E). Similar results were found in insulin-treated HepG2 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S6E). We verified these results in Hpn−/− mice by i.v. rHGF bolus injection. After the treatment, Met, Akt, Gsk3α/β, and mTOR phosphorylation increased in Hpn−/− livers (Fig. 3G and SI Appendix, Fig. S6F). Liver glycogen levels also increased in Hpn−/− mice (Fig. 3H). In WT mice, similar rHGF treatment increased Met, Akt, Gsk3α/β, and mTOR phosphorylation (Fig. 3G and SI Appendix, Fig. S6F). However, liver glycogen levels were unchanged (Fig. 3H). These results indicate that impaired pro-HGF processing and hence low HGF levels are likely responsible for the reduced Met signaling and associated phenotypes in Hpn−/− mice. In rHGF-treated Hpn−/− and WT mice, we did not detect significant changes in blood glucose and lipid levels, indicating that a single injection of rHGF is insufficient to alter systemic glucose and lipid levels in mice.

Adipose Tissues in Hpn−/− Mice Exhibit a Browning Phenotype.

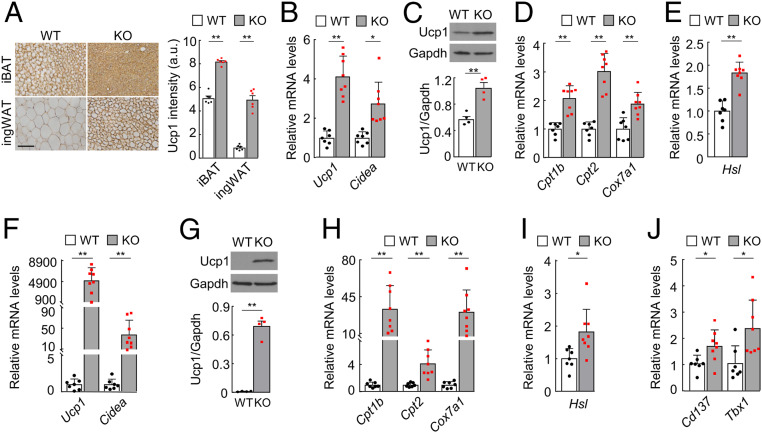

To understand the morphological changes in Hpn−/− adipocytes, we immune-stained Ucp1 (uncoupling protein 1), a brown adipocyte marker (35, 36), in adipose tissues. High levels of Ucp1 staining were found in iBAT and all WAT examined, except epididymal WAT (eWAT), in Hpn−/− mice (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). In qRT-PCR and Western blotting, increased Ucp1 mRNA (Fig. 4B) and protein (Fig. 4C and SI Appendix, Fig. S7B) levels were confirmed in Hpn−/− iBAT. Moreover, high mRNA levels of Cidea (Cell Death-Inducing DFFA-Like Effector A, another brown adipocyte marker) (36) (Fig. 4B); mitochondrial genes Cpt1b, Cpt2, and Cox7a1 (Fig. 4D); and the hormone-sensitive lipase gene (Hsl; Fig. 4E) were found in Hpn−/− iBAT. Similar results of increased Ucp1, Cidea, Cpt1b, Cpt2, Cox7a1, and Hsl expression were detected in Hpn−/− ingWAT (Fig. 4 F–I and SI Appendix, Fig. S7C). In addition, levels of Cd137 and Tbx1 mRNA (two beige adipocyte markers) (36) were also higher in Hpn−/− ingWAT (Fig. 4J). These results indicate a browning phenotype in Hpn−/− adipose tissues.

Fig. 4.

Expression of brown and beige adipocyte markers in iBAT and ingWAT. (A) Uncoupling protein 1 (Ucp1) staining in iBAT and ingWAT from 4–5-mo-old male WT and Hpn−/− (KO) mice. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) Ucp1 staining intensities in arbitrary units (a.u.) were calculated with Image Pro software (n = 6). (B) Relative Ucp1 and Cidea mRNA levels in iBAT from WT and KO mice, as analyzed by qRT-PCR (n = 7–8). (C) Western blotting of Ucp1 protein in iBAT from WT and KO mice (n = 4). Gapdh was a loading control. Quantitative data from four Western blots are shown in the bar graph. The other three sets of blots are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S6B. (D–G) qRT-PCR analysis of Cpt1b, Cpt2, and Cox7a1 (D) and Hsl (E) mRNA levels in iBAT from WT and KO mice (n = 7–8). (F) qRT-PCR analysis of Ucp1 and Cidea mRNA levels in ingWAT from WT and KO mice (n = 7–8). (G) Western blotting of Ucp1 protein in ingWAT from WT and KO mice (n = 4). Quantitative data from four Western blots are shown in the bar graph. The other three blots are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S6C. (H–J) qRT-PCR analysis of Cpt1b, Cpt2, and Cox7a1 (H); Hsl (I); and Cd137 and Tbx1 (J) mRNA levels in ingWAT from WT and KO mice (n = 7–8). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

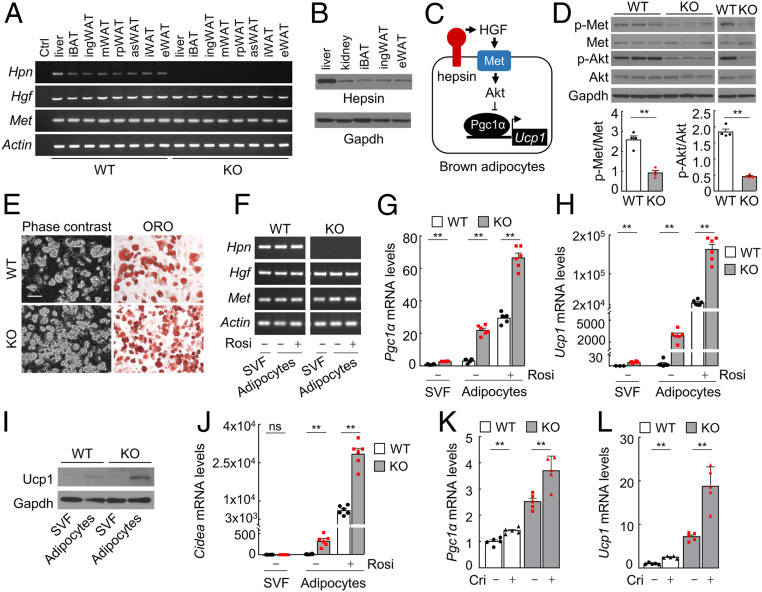

Hepsin Deficiency Enhances Browning of Cultured Adipocytes from IBAT and IngWAT.

To understand if the observed browning phenotype in Hpn−/− mice is due to a lack of direct hepsin function in adipose tissues or indirect systemic effects, we examined Hpn expression in adipose tissues by RT-PCR and Western blotting. Hpn, Hgf, and Met mRNA were expressed in all adipose tissues analyzed in WT mice (Fig. 5A). Hepsin protein levels in adipose tissues were lower than that in the liver but comparable to that in the kidney, which is known for hepsin expression (Fig. 5B). These data support a direct role of hepsin in adipose tissues. Akt is known to inhibit Ucp1 expression in brown adipocytes in a Pgc1α-dependent mechanism (37). Possibly, hepsin enhances this mechanism via HGF activation and Met signaling (Fig. 5C). In supporting this hypothesis, Met and Akt phosphorylation decreased in Hpn−/− iBAT (Fig. 5D), consistent with increased Ucp1 expression in Hpn−/− iBAT.

Fig. 5.

Hepsin expression and function in adipocytes. (A) RT-PCR analysis of Hpn (encoding hepsin), Hgf (encoding pro-HGF), and Met expression in adipose tissues from WT and Hpn−/− (KO) mice. Ctrl, no cDNA template; i, interscapular; ing, inguinal; m, mesenteric; rp, retroperitoneal; as, anterior subcutaneous; e, epididymal. (B) Western blotting of mouse hepsin in the liver, kidney, iBAT, ingWAT, and eWAT. (C) A proposed role of hepsin in brown adipocytes. Hepsin activates HGF, which in turn activates Met and Akt, thereby inhibiting Pgc1α and Ucp1 expression. (D) Western blotting of Met and Akt phosphorylation in iBAT from WT and KO mice. Phosphorylated vs. unphosphorylated protein ratios were calculated on the basis of densitometry (n = 4). (E) Phase-contrast (Left) and ORO-stained (Right) images of adipocytes from iBAT-derived stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells. (Scale bar, 100 μm.) (F) RT-PCR analysis of Hpn, Hgf, and Met expression in iBAT-derived SVF cells before and after differentiation with rosiglitazone (Rosi). (G and H) qRT-PCR analysis of Pgc1α (G) and Ucp1 (H) mRNA levels in iBAT-derived cells (n = 3–6). (I) Western blotting of Ucp1 protein expression in iBAT-derived cells. (J) qRT-PCR analysis of Cidea mRNA levels in iBAT-derived cells (n = 3–5). (K and L) qRT-PCR analysis of Pgc1α (K) and Ucp1 (L) mRNA levels in brown adipocytes treated with buffer (−) or crizotinib (+; n = 5). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). ns, not significant.

To verify if hepsin regulates adipocyte browning, we isolated stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells from WT and Hpn−/− iBAT and differentiated them into adipocytes in culture with rosiglitazone. Differentiated adipocytes from WT and Hpn−/− iBAT contained lipid droplets, as shown by Oil Red O (ORO) staining (Fig. 5E), and had similar expression levels of the Adn gene (encoding adipsin, an adipocyte marker; SI Appendix, Fig. S7D). In RT-PCR (Fig. 5F), Hpn, Hgf, and Met expression was detected in SVF cells from WT mice before and after the differentiation. In Hpn−/− iBAT-derived cells, Hgf and Met, but not Hpn, expression was detected (Fig. 5F). Pgc1α, Ucp1, and Cidea mRNA and Ucp1 protein levels were all higher in the differentiated Hpn−/− adipocytes than in WT controls (Fig. 5 G–J). Hpn−/− adipocytes also had higher O2 consumption rate (OCR) values than those in WT adipocytes under basal and palmitate- or norepinephrine-induced conditions (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 E and F). When WT and Hpn−/− brown adipocytes were treated with crizotinib, a Met inhibitor, Pgc1α and Ucp1 up-regulation was observed, supporting a role of Met signaling in Ucp1 expression (Fig. 5 K and L). In parallel experiments, decreased Met and Akt phosphorylation was found in Hpn−/− ingWAT (SI Appendix, Fig. S8A), whereas Ucp1 and Cd137 mRNA and Ucp1 protein levels were higher in differentiated Hpn−/− ingWAT adipocytes, compared to those in WT controls (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 B–F). Hpn−/− ingWAT adipocytes also had higher OCR values under basal and palmitate-induced conditions (SI Appendix, Fig. S7G). Additionally, crizotinib increased, whereas rHGF decreased, Ucp1 expression in WT and Hpn−/− ingWAT adipocytes in culture (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 H and I). Together, these data indicate that hepsin plays a role in regulating adipose tissue phenotype in a tissue-specific manner.

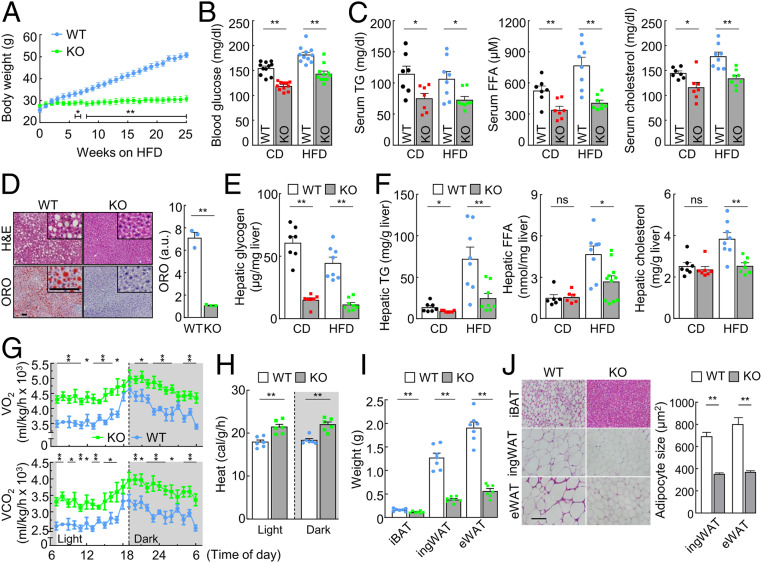

Hpn−/− Mice Are Resistant to High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity and Diabetes.

If hepsin deficiency reduces liver metabolism, enhances adipocyte browning, and increases metabolic rates, such a phenotype may lower the risk of diabetes and obesity. To test this hypothesis, we fed WT and Hpn−/− mice a high-fat diet (HFD), which caused substantial body weight gains in WT mice but much less in Hpn−/− mice (Fig. 6A and SI Appendix, Fig. S9A). Levels of blood glucose, triglyceride, FFA, and cholesterol were all lower in Hpn−/− than WT mice on HFD (Fig. 6 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). Lipid accumulation was found in liver sections from WT, but barely in Hpn−/−, mice on HFD (Fig. 6D). Hepatic glycogen, triglyceride, FFA, and cholesterol levels were also lower in HFD-fed Hpn−/− mice (Fig. 6 E and F). These results indicate that hepsin deficiency prevents HFD-induced obesity, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia in mice.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of Hpn−/− mice on high-fat diet. (A) Body weights of male WT and Hpn−/− (KO) mice on a high-fat diet (HFD; n = 5–6), starting at 12 wk of age (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, WT vs. KO at the same time points). (B and C) Nonfasting blood glucose (n = 11; B) and serum triglyceride (TG), free fatty acid (FFA), and cholesterol (n = 7–8; C) levels after 14 wk of chow diet (CD) or HFD. (D) H&E- and ORO-stained liver sections from male mice on HFD. High-magnification (×200) images are shown in upper right corners. (Scale bar, 30 μm.) Quantitative data of ORO staining by ImageJ analysis from three mice per group are shown in the bar graph. a.u., arbitrary unit. (E and F) Hepatic glycogen (E) and TG, FFA, and cholesterol (F) levels in mice on CD and HFD (n = 6–8). (G and H) O2 consumption (VO2), CO2 production (VCO2; G), and heat generation (“H”) in 4–5-mo-old male mice on HFD in light and dark cycles (n = 12; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. WT at the same time point for VO2 and VCO2.) (I) Adipose weights in 7-mo-old male mice on HFD for 12 wk (n = 7). (J) H&E-stained adipose sections. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) Adipocyte sizes were measured with ImageJ software in randomly selected fields. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). ns, not significant.

In metabolic studies, HFD-fed Hpn−/− mice had higher rates of O2 consumption, CO2 production, and heat generation (Fig. 6 G and H and SI Appendix, Fig. S9 C and D) compared with those in HFD-fed WT mice, despite similar motor activities between Hpn−/− and WT mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S9E). Food intakes were higher in HFD-fed Hpn−/− mice, whereas fecal lipid levels were similar between Hpn−/− and WT mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S9E). Consistently, less adipose weights and smaller adipocyte sizes were found in HFD-fed Hpn−/− mice (Fig. 6 I and J and SI Appendix, Fig. S9 F–H). In contrast, WT and Hpn−/− mice had similar levels of serum adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), α-melanocyte–stimulating hormone (α-MSH), β-endorphin, and agouti-related peptide (AGRP), which are known to regulate energy metabolism (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 A–D). These results indicate that increased metabolic rates and hence energy consumption are likely responsible for the observed phenotype in HFD-fed Hpn−/− mice.

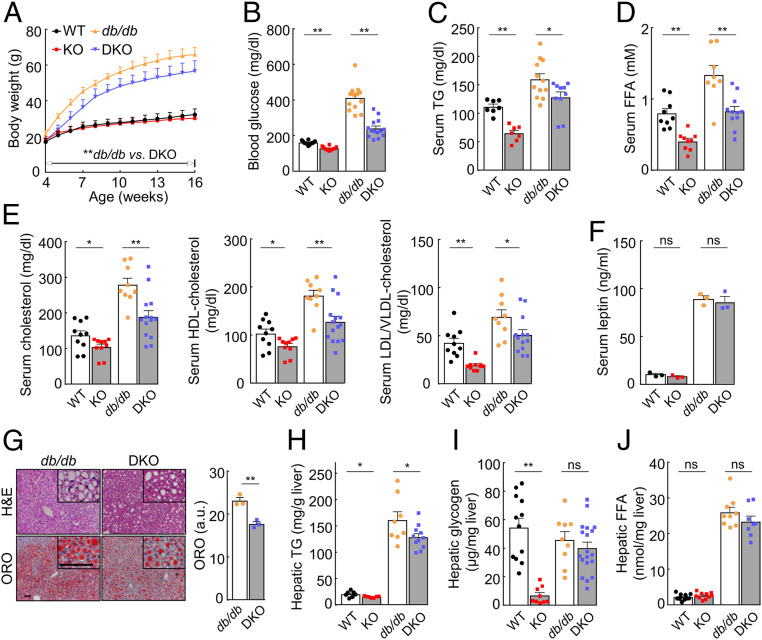

We next examined the effect of hepsin deficiency on db/db mice that are obese and diabetic due to leptin receptor deficiency (38). We generated Hpn−/− and db/db double knockout (DKO) mice. Compared with db/db mice on a chow diet, DKO mice had ∼14 to 24% less body weights (P values < 0.001), starting at 4 wk of age (Fig. 7A). DKO mice also had lower blood glucose and lipid levels (Fig. 7 B–E), despite elevated serum leptin levels (Fig. 7F). In liver sections, lipid accumulation was ∼24% less in DKO mice than db/db mice (Fig. 7G). A similar reduction in hepatic triglyceride levels was observed in DKO mice (Fig. 7H). Hepatic glycogen and FFA levels appeared lower, although not statistically significantly, in DKO than db/db mice (Fig. 7 I and J). These results show that hepsin deficiency reduces the severity of obesity and diabetes in db/db mice, which is consistent with the findings in HFD-fed Hpn−/− mice.

Fig. 7.

Effects of hepsin deficiency on db/db mice. (A) Body weights of male WT, Hpn−/− (KO), db/db, and double knockout (DKO) mice on a chow diet (n = 11–26). (B–E) Nonfasting blood glucose (n = 12–14; B) and serum TG (n = 7–12; C), FFA (n = 8–11; D), and cholesterol (n = 9–14; E) levels in 17-wk-old mice on a chow diet. (F) Serum leptin levels in WT, KO, db/db, and DKO mice (n = 3). (G) H&E- and ORO-stained liver sections from 12-wk-old male db/db and DKO mice on a chow diet. High-magnification (×200) images are shown in upper right corners. (Scale bar, 30 µm.) Quantitative data of ORO staining from ImageJ analysis of sections from three mice per group are presented in the bar graph. a.u., arbitrary unit. (H–J) Hepatic TG (n = 7–11; H), glycogen (n = 9–19; I), and FFA (n = 8–12; J) levels in 17-wk-old male mice on a chow diet. Data are presented as mean ± SD (A) or mean ± SEM (B–J). In A, **P < 0.01 db/db vs. DKO at the same time points during the period indicated; in B–J, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ns, not significant.

Hepsin Expression in Mice That Are Obese or Subjected to Fasting or Cold Exposure.

To understand if hepsin expression is regulated under pathophysiological conditions, we analyzed hpn expression in db/db mice on normal chow diet and in WT mice on HFD or subjected to fasting/refeeding or cold exposure (4 °C). By qRT-PCR, we found that db/db mice had lower levels of hpn expression in the liver and adipose tissues (ingWAT and eWAT) compared with those in control WT mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S11A). In WT mice on HFD for 5 wk or subjected to 12-h fasting without or with 24-h refeeding, hpn expression in the liver and adipose tissues did not change significantly (SI Appendix, Fig. S11 B and C). In contrast, hpn mRNA levels in the liver and ingWAT were increased in WT mice exposed to cold (SI Appendix, Fig. S11D). The levels in iBAT and eWAT were also higher, although not statistically significantly, in the cold-exposed WT mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S11D). These results suggest that hepsin may be regulated in response to genetic and environmental changes.

Discussion

Proteolytic enzymes are essential in many biological processes (39, 40). Hepsin was identified three decades ago (6), but its function remains poorly defined. Previous studies indicated a role of hepsin in embryonic development (41), blood coagulation (42), and hepatocyte growth (18). Hpn−/− mice, however, are viable and exhibit no detectable defects in hemostasis and liver regeneration (19, 20). In this study, we uncovered an important function of hepsin in promoting liver metabolism, as indicated by low levels of blood glucose, triglyceride, FFA, and cholesterol (both HDL and LDL/VLDL cholesterols) and low levels of liver glycogen and triglyceride in Hpn−/− mice. In a previous study, reduced serum HDL cholesterol levels were reported in a mutant mouse line, in which random chemical mutagenesis reduced Hpn expression in the liver (43). In another genome-wide association study, the human HPN gene was identified as a major locus for serum albumin levels in European and Japanese populations (44). Albumin is produced by the liver and accounts for ∼50% of total plasma proteins. These data are consistent with our findings, supporting a critical role of hepsin in promoting glycogen, lipid, and protein synthesis in the liver.

Unexpectedly, Hpn−/− mice were found to have a high basal metabolic rate, as indicated by increased O2 consumption, CO2 production, respiratory exchange ratio, and heat generation in both light and dark cycles, which is independent of motor activities. This phenotype is likely due to increased brown adipocytes that are rich in mitochondria, metabolically active, and thermogenic (45, 46). We show that Hpn−/− iBAT and ingWAT had higher rates of glucose intakes when assayed in vitro. Cultured adipocytes from Hpn−/− iBAT and ingWAT also exhibited higher O2 consumption rates. Moreover, Hpn−/− adipocytes in iBAT and WATs were smaller in size and had higher levels of Ucp1 and Cidea; mitochondrial Cpt1b, Cpt2, and Cox7a1; and lipase Hsl expression. These data indicate that hepsin has a regulatory function in adipose tissues by inhibiting adipocyte browning.

Met and its downstream molecules, including AKT, GSK3, and mTOR, play a key role in glucose, lipid, and protein synthesis in many cell types (29, 33, 34). In our study, decreased Met, Akt, Gsk3α/β, and mTOR phosphorylation was found in Hpn−/− livers, indicating that reduced Met signaling is responsible for low levels of hepatic glycogen, lipid, and protein synthesis in these mice. This defect is likely caused by reduced generation of HGF, which activates Met (28, 29). We show that Hpn−/− mice had high levels of pro-HGF in the liver but low levels of serum HGF, indicating that pro-HGF–to–HGF conversion, but not Hgf expression, is impaired in Hpn−/− livers. The reduced level, but not the absence, of serum HGF in Hpn−/− mice indicates that other protease(s) likely contribute to pro-HGF processing in vivo. Among them, HGF activator (47), matriptase (48, 49), and plasma kallikrein and blood clotting factors (25, 50), which were shown to activate HGF in vitro, are possible candidates.

Hepsin has a transmembrane domain that anchors the protein on the cell surface (6, 16). Thus, hepsin is expected to function in the tissues where it is expressed. By RT-PCR and Western blotting, we detected Hpn, Hgf, and Met expression in all adipose tissues examined in WT mice, suggesting a local mechanism by which hepsin mediates HGF activation and Met signaling. Previously, Akt signaling was shown to block Ucp1 expression in adipocytes in a Pgc1α-dependent mechanism (37). In this study, we found decreased Met and Akt phosphorylation in Hpn−/− iBAT and increased Pgc1α, Ucp1, and Cidea expression and respiration rates in differentiated Hpn−/− brown adipocytes, where the Met inhibitor crizotinib increased Pgc1α and Ucp1 expression. Moreover, we found increased Ucp1 and CD137 mRNA expression and respiration rates in differentiated Hpn−/− ingWAT adipocytes, where crizotinib increased, whereas rHGF decreased, Ucp1 expression. These data are consistent, indicating that hepsin acts in adipose tissues in a cell-autonomous manner to enhance Met/Akt signaling, thereby inhibiting adipocyte browning. Together, these data show that hepsin functions separately in the liver and adipose tissues to regulate metabolic and energy homeostasis. In this regard, hepsin is similar to corin, another type II transmembrane serine protease, which has been shown to function separately in the heart and the pregnant uterus to regulate cardiovascular homeostasis (12, 51). Further tissue-specific knockout and rescue experiments in animal models are important to define the role of hepsin in separate tissues.

In humans, high plasma HGF levels have been associated with diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and heart disease (52–54), suggesting that increased HGF expression and/or activation may be detrimental to metabolic and cardiovascular homeostasis. In this study, we show that hepsin-mediated HGF activation and subsequent Met signaling enhance liver glucose and lipid metabolism, inhibit adipocyte browning, and lower metabolic rates. In principle, when energy supply is abundant, enhanced hepsin activity could increase HGF production and the risk of diabetes and obesity, whereas reduced hepsin activity may decrease HGF production and lower the risk of metabolic disease. In supporting this idea, we show that Hpn−/− mice are remarkably resistant to HFD-induced hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and obesity. Moreover, hepsin deficiency reduces the severity of obesity and diabetes in db/db mice. Interestingly, hepsin expression in the liver and adipocytes may be regulated by genetic and environmental factors, as suggested in studies with db/db mice and cold-exposed WT mice. At this time, it is unclear if the observed changes reflect a specific mechanism in controlling hepsin expression in individual tissues or an indirect systemic response to disturbed metabolic and thermal homeostasis. Additional studies are required to understand the mechanism and significance of hepsin regulation in liver metabolism and thermogenesis.

In summary, hepsin is a transmembrane serine protease highly expressed in the liver, but its physiological function remained elusive for three decades. Our results show that hepsin promotes liver metabolism by enhancing HGF generation and Met signaling in mice. This hepsin- and HGF-mediated mechanism also acts in adipose tissues to inhibit adipocyte browning, thereby reducing basic metabolic rates. These findings indicate that hepsin is an important regulator in liver and energy metabolism. Proteases are well-known therapeutic targets (55). Our findings suggest that inhibition of hepsin may be exploited to treat metabolic diseases such diabetes and obesity.

Materials and Methods

All animal studies were approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All of the methods, including those involving mice; HepG2 cells and primary hepatocytes and adipocytes; blood glucose; glucose tolerance test and insulin tolerance test; plasma insulin and glucagon; tissue glycogen; serum lipids and proteins; hepatic triglyceride; FFA and cholesterols; metabolic studies; fecal lipids; histology and immune staining; glucose uptake by iBAT and ingWAT; serum HGF; Western blotting; RNA extraction; cDNA synthesis and qRT-PCR; glycogen levels in hepatocytes; rHGF injection in mice; adipocyte OCR measurement; high-fat diet treatment; serum ACTH, α-MSH, β-endorphin, and AGRP levels; hepsin deficiency in db/db mice; and statistical analysis, are described in the SI Appendix.

Data Availability Statement.

All data for the paper are presented in the main text or SI Appendix. Additional information for associated protocols and materials in the paper is available upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank current and former lab members for their valuable inputs to this project and Rakhee Banerjee for assisting in animal experiments. This study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL126697, DK120679, AA024333, HL147823), the American Heart Association (19POST34380460), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81873566), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutes in China.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1918445117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Brunt E. M., Pathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7, 195–203 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen J. C., Horton J. D., Hobbs H. H., Human fatty liver disease: Old questions and new insights. Science 332, 1519–1523 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haas J. T., Francque S., Staels B., Pathophysiology and mechanisms of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 78, 181–205 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petersen M. C., Vatner D. F., Shulman G. I., Regulation of hepatic glucose metabolism in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 13, 572–587 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Q., Vijayakumar A., Kahn B. B., Metabolites as regulators of insulin sensitivity and metabolism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 654–672 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leytus S. P., Loeb K. R., Hagen F. S., Kurachi K., Davie E. W., A novel trypsin-like serine protease (hepsin) with a putative transmembrane domain expressed by human liver and hepatoma cells. Biochemistry 27, 1067–1074 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Q., Type II transmembrane serine proteases. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 54, 167–206 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bugge T. H., Antalis T. M., Wu Q., Type II transmembrane serine proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23177–23181 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hooper J. D., Clements J. A., Quigley J. P., Antalis T. M., Type II transmembrane serine proteases. Insights into an emerging class of cell surface proteolytic enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 857–860 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antalis T. M., Bugge T. H., Wu Q., Membrane-anchored serine proteases in health and disease. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 99, 1–50 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen S. et al., PCSK6-mediated corin activation is essential for normal blood pressure. Nat. Med. 21, 1048–1053 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cui Y. et al., Role of corin in trophoblast invasion and uterine spiral artery remodelling in pregnancy. Nature 484, 246–250 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du X. et al., The serine protease TMPRSS6 is required to sense iron deficiency. Science 320, 1088–1092 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szabo R., Bugge T. H., Membrane-anchored serine proteases in vertebrate cell and developmental biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 27, 213–235 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanabe L. M., List K., The role of type II transmembrane serine protease-mediated signaling in cancer. FEBS J. 284, 1421–1436 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuji A. et al., Hepsin, a cell membrane-associated protease. Characterization, tissue distribution, and gene localization. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 16948–16953 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu Y. C. et al., Serine protease hepsin regulates hepatocyte size and hemodynamic retention of tumor cells by hepatocyte growth factor signaling in mice. Hepatology 56, 1913–1923 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torres-Rosado A., O’Shea K. S., Tsuji A., Chou S. H., Kurachi K., Hepsin, a putative cell-surface serine protease, is required for mammalian cell growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 7181–7185 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Q. et al., Generation and characterization of mice deficient in hepsin, a hepatic transmembrane serine protease. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 321–326 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu I. S. et al., Mice deficient in hepsin, a serine protease, exhibit normal embryogenesis and unchanged hepatocyte regeneration ability. Thromb. Haemost. 84, 865–870 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brunati M. et al., The serine protease hepsin mediates urinary secretion and polymerisation of Zona Pellucida domain protein uromodulin. eLife 4, e08887 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guipponi M. et al., Mice deficient for the type II transmembrane serine protease, TMPRSS1/hepsin, exhibit profound hearing loss. Am. J. Pathol. 171, 608–616 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olinger E. et al., Hepsin-mediated processing of uromodulin is crucial for salt-sensitivity and thick ascending limb homeostasis. Sci. Rep. 9, 12287 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu Q., Parry G., Hepsin and prostate cancer. Front. Biosci. 12, 5052–5059 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herter S. et al., Hepatocyte growth factor is a preferred in vitro substrate for human hepsin, a membrane-anchored serine protease implicated in prostate and ovarian cancers. Biochem. J. 390, 125–136 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirchhofer D. et al., Hepsin activates pro-hepatocyte growth factor and is inhibited by hepatocyte growth factor activator inhibitor-1B (HAI-1B) and HAI-2. FEBS Lett. 579, 1945–1950 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xuan J. A. et al., Antibodies neutralizing hepsin protease activity do not impact cell growth but inhibit invasion of prostate and ovarian tumor cells in culture. Cancer Res. 66, 3611–3619 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamura T., Sakai K., Nakamura T., Matsumoto K., Hepatocyte growth factor twenty years on: Much more than a growth factor. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 26 (suppl. 1), 188–202 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trusolino L., Bertotti A., Comoglio P. M., MET signalling: Principles and functions in development, organ regeneration and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 834–848 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basilico C., Arnesano A., Galluzzo M., Comoglio P. M., Michieli P., A high affinity hepatocyte growth factor-binding site in the immunoglobulin-like region of Met. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21267–21277 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirchhofer D. et al., Utilizing the activation mechanism of serine proteases to engineer hepatocyte growth factor into a Met antagonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 5306–5311 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landgraf K. E. et al., Allosteric peptide activators of pro-hepatocyte growth factor stimulate Met signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 40362–40372 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krycer J. R., Sharpe L. J., Luu W., Brown A. J., The Akt-SREBP nexus: Cell signaling meets lipid metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 21, 268–276 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laplante M., Sabatini D. M., An emerging role of mTOR in lipid biosynthesis. Curr. Biol. 19, R1046–R1052 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chouchani E. T., Kazak L., Spiegelman B. M., New advances in adaptive thermogenesis: UCP1 and beyond. Cell Metab. 29, 27–37 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Jong J. M., Larsson O., Cannon B., Nedergaard J., A stringent validation of mouse adipose tissue identity markers. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 308, E1085–E1105 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ortega-Molina A. et al., Pten positively regulates brown adipose function, energy expenditure, and longevity. Cell Metab. 15, 382–394 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi K. et al., The db/db mouse, a model for diabetic dyslipidemia: Molecular characterization and effects of Western diet feeding. Metabolism 49, 22–31 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Overall C. M., Blobel C. P., In search of partners: Linking extracellular proteases to substrates. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 245–257 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perona J. J., Craik C. S., Structural basis of substrate specificity in the serine proteases. Protein Sci. 4, 337–360 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vu T. K., Liu R. W., Haaksma C. J., Tomasek J. J., Howard E. W., Identification and cloning of the membrane-associated serine protease, hepsin, from mouse preimplantation embryos. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 31315–31320 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kazama Y., Hamamoto T., Foster D. C., Kisiel W., Hepsin, a putative membrane-associated serine protease, activates human factor VII and initiates a pathway of blood coagulation on the cell surface leading to thrombin formation. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 66–72 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aljakna A. et al., Pla2g12b and Hpn are genes identified by mouse ENU mutagenesis that affect HDL cholesterol. PLoS One 7, e43139 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Franceschini N. et al.; LifeLines Cohort Study , Discovery and fine mapping of serum protein loci through transethnic meta-analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 91, 744–753 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cannon B., Nedergaard J., Brown adipose tissue: Function and physiological significance. Physiol. Rev. 84, 277–359 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen P., Spiegelman B. M., Brown and beige fat: Molecular parts of a thermogenic machine. Diabetes 64, 2346–2351 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyazawa K. et al., Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the cDNA for a human serine protease reponsible for activation of hepatocyte growth factor. Structural similarity of the protease precursor to blood coagulation factor XII. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 10024–10028 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirchhofer D. et al., Tissue expression, protease specificity, and Kunitz domain functions of hepatocyte growth factor activator inhibitor-1B (HAI-1B), a new splice variant of HAI-1. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36341–36349 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee S. L., Dickson R. B., Lin C. Y., Activation of hepatocyte growth factor and urokinase/plasminogen activator by matriptase, an epithelial membrane serine protease. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 36720–36725 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peek M., Moran P., Mendoza N., Wickramasinghe D., Kirchhofer D., Unusual proteolytic activation of pro-hepatocyte growth factor by plasma kallikrein and coagulation factor XIa. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 47804–47809 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan W., Wu F., Morser J., Wu Q., Corin, a transmembrane cardiac serine protease, acts as a pro-atrial natriuretic peptide-converting enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8525–8529 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akour A. et al., Levels of metabolic markers in drug-naive prediabetic and type 2 diabetic patients. Acta Diabetol. 54, 163–170 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiratsuka A. et al., Strong association between serum hepatocyte growth factor and metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 2927–2931 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rehman J. et al., Obesity is associated with increased levels of circulating hepatocyte growth factor. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 41, 1408–1413 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drag M., Salvesen G. S., Emerging principles in protease-based drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 690–701 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data for the paper are presented in the main text or SI Appendix. Additional information for associated protocols and materials in the paper is available upon request.