Abstract

Mitochondria have their own genomes and their own agendas. Like their primitive bacterial ancestors, mitochondria interact with their environment and organelle colleagues at their physical interfaces, the outer mitochondrial membrane. Among outer membrane proteins, mitofusins (MFN) are increasingly recognized for their roles as arbiters of mitochondria-mitochondria and mitochondria-reticular interactions. This review examines the roles of MFN1 and MFN2 in the heart and other organs as proteins that tether mitochondria to each other or to other organelles, and as mitochondrial anchoring proteins for various macromolecular complexes. The consequences of MFN-mediated tethering and anchoring on mitochondrial fusion, motility, mitophagy, and mitochondria-ER calcium cross-talk are reviewed. Pathophysiological implications are explored from the perspective of mitofusin common functioning as tethering and anchoring proteins, rather than as mediators of individual processes. Finally, some informed speculation is provided for why mouse MFN knockout studies show severe multi-system phenotypes whereas rare human diseases linked to MFN mutations are limited in scope.

Keywords: Mitochondrial dynamics, mitochondrial transport, mitochondrial fusion, mitophagy, metabolism

Background

Tether: a rope or chain with which an animal is tied to restrict its movement.

Anchor: a device used to connect a vessel to the bed of a body of water to prevent drifting.

Mitochondria are descendants of primordial bacteria that invaded, and ultimately became permanent residents within, ancient Archaea-like single cell organisms [1, 2]. The mutual benefits afforded by this relationship include greater energy supply to fuel more powerful metabolism for the host, and physical protection with infrastructure support (protein, lipid synthesis and caretaking of genomes) for mitochondria. Thus, a transition from endosymbiont to organelle occurred approximately 1.5 billion years ago, arguably enabling multicellular life as we now know it.

Mechanisms by which mitochondria could communicate with their host cells, and vice versa, were required for successful organellar integration. Recognizing that ~99% of their original bacterial genomes were exported by mitochondria to their host cells [3], a great deal of effort has been devoted to dissecting mitochondria-nucleus communications that orchestrate transcription and translation of nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial proteins. Our understanding of these processes remains incomplete, but it is evident that this form of communication does not require direct physical contact, i.e. tethering, between mitochondria and nucleus. There is also compelling evidence that mitochondria can communicate at a distance with each other and other organelles by releasing discreet packets of messaging factors, analogous to conventional vesicular transmission [4, 5]. However, the typical means of communicating between individual mitochondria, or between mitochondria and other cellular organelles, requires highly defined physical contact sites between the organelles.

Physical sites at which mitochondria are connected to endoplasmic reticulum (ER; or in striated muscle, sarcoplasmic reticulum [SR]) were originally observed by Bernhard using electron microscopy [6, 7], and have since been designated Mitochondria Associated Membranes, or MAMs. MAMs were described in functional terms as ER-mitochondria membrane interacting sites at which vesicle-independent transfer of phosphatidylserine from ER to mitochondria occurs [8, 9]. Subsequent studies expanded the portfolio of MAM functionality to include Ca2+ transport from ER to mitochondria [10]. Calcium delivered to mitochondria can, depending upon the concentration, either stimulate ATP production via oxidative phosphorylation [11, 12] or activate mitochondria-mediated cell death programs through stimulation of apoptosis and activation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore [13–16]. Because mitochondrial calcium uptake requires that Ca2+ be delivered to the organelle at concentrations of at least 2–5 uM [17, 18], the concept of calcium microdomains [19] was integrated with observations of physical MAMs to create the current paradigm: mitochondrial-ER/SR contact sites facilitate mitochondrial sensing of ER/SR calcium release in order to orchestrate and direct contextually-appropriate cellular responses.

Early studies used proteolytic enzymes to disrupt ER-mitochondrial contact sites and show that MAMs resulted from interactions between proteinaceous “tethers” on each organelle [20, 21]. Subsequently, de Brito and Scorrano identified the mitochondrialouter membrane fusion protein mitofusin (MFN) 2 as the first example of a definitive mitochondrial tethering protein [22]. This review describes how the potential pathophysiological roles played by mitofusin-mediated organelle tethering and macromolecule anchoring have evolved as our understanding of the multi-functionality of these ubiquitous proteins has expanded. Phenomenological and observational data (of which there is an abundance) are distinguished from specific mechanistic results. I conclude with a discussion of how pathological perturbations of various MFN2-mediated processes can impact different organ systems and manifest as distinct clinical syndromes.

MFNs are mitochondrial tethering proteins that control mitochondrial fusion.

Physical association is the obvious obligate first step in fusing two mitochondria. This “meeting of the mitochondria” is mediated by mitofusin (MFN)1 and MFN2, the mammalian orthologs of yeast fuzzy onion (fzo). Mitofusins were named for their ability to promote mitochondrial outer membrane fusion; in this capacity they also act as mitochondria-mitochondria tethers. As described in detail elsewhere [23–25], mitochondrial fusion is mediated by the coordinated actions of three mitochondrial fusion proteins, MFN1, MFN2 and optic atrophy 1 (OPA1). Because mitochondria have physically and functionally distinct outer and inner membranes, physically and temporally distinct outer and inner membrane fusion events are required to complete organelle fusion. Thus, outer membrane MFN1 and MFN2 proteins mediate outer membrane fusion whereas inner membrane OPA1 mediates inner membrane fusion.

The lack of pharmacological or chemical tools by which MFN or OPA function could be specifically manipulated mandated that targeted gene ablation be the major technique by which separation-of-function according to mitochondrial fusion protein membrane localization was demonstrated. Accordingly, genetic deletion of either Mfn1 or Mfn2 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts impaired the initial steps in mitochondrial fusion, thereby altering the dynamic balance in favor of mitochondrial fission and producingcells with abnormally short, so-called “fragmented”, mitochondria. Completely abolishing mitochondrial fusion by combined ablation of Mfn1 and Mfn2 produced cells with small round mitochondria, a high proportion of which showed evidence of inner membrane electrochemical gradient dissipation (i.e. impaired mitochondrial respiration) [26]. Importantly, forced expression of either Mfn1 or Mfn2 rescued all of the Mfn knockout fibroblast phenotypes (i.e. Mfn1 KO, Mfn2 KO, and Mfn1/Mfn2 double KO), demonstrating functional overlap between Mfn1 and Mfn2 for mitochondrial fusion [27]. By comparison to mitofusin deletion, ablation of Opa1 produced large mitochondria with multiple individual matrixes (like an egg with two yolks), which has been interpreted as interruption of fusion after the outer mitochondrial membranes had combined, but before inner membrane fusion [28, 29]. These observations led to the description of distinct physical steps of outer and inner membrane fusion: Mitochondria first physically and reversibly associate (tethering). Then, outer membranes fuse in a GTPase-dependent manner via the actions of MFN1 and MFN2. Finally, inner membranes fuse in a GTPase-dependent manner via OPA1 [24].

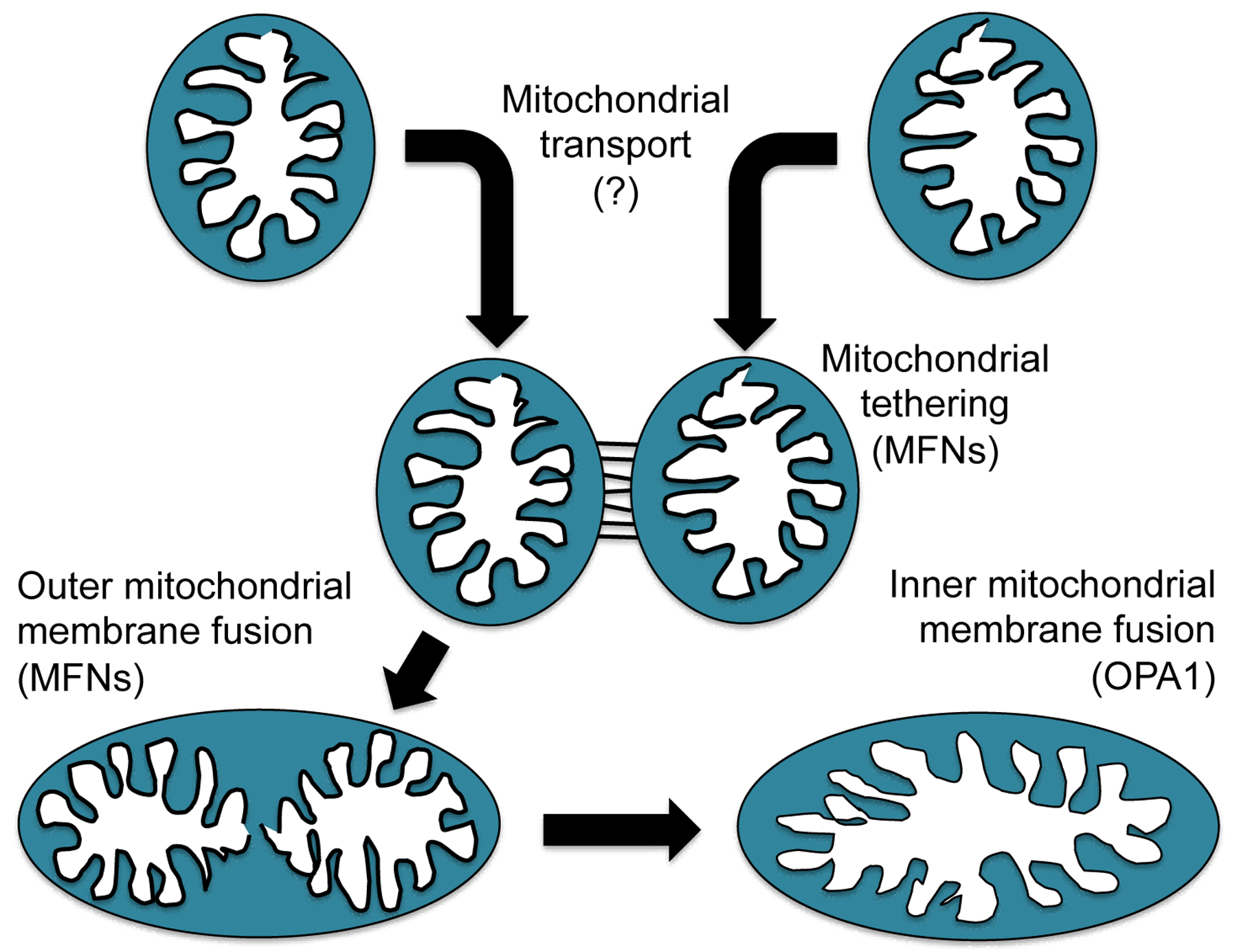

The biological signals that initiate and regulate mitochondrial fusion are poorly understood. We envision that mitochondrial fusion is not simply a random occurrence between pairs of mitochondria that happen to bump into one another. Rather, specific bioenergetically favorable mitochondrial pairing events need to be nurtured. For example, “young” mitochondria (i.e. the newly formed daughters of either replicative or asymmetrical mitochondrial fission events) need to integrate either with existing members of the mitochondrial collective or other small daughters to form normal mature mitochondria. Likewise, individual mitochondria may need to fuse with integrated mitochondrial networks at specific locales during highly organized mitochondrial network remodeling. Finally, fusion between functionally-impaired and healthy mitochondria as part of repair-by-complementation [30, 31] requires that the “sick” organelle be paired with a “healthy” partner. Thus, mitochondrial pairing events should be contextually appropriate in time and space, bringing together partners having characteristics desired for given fusion events. When these processes are not properly orchestrated, as with fusion between severely impaired mitochondria targeted for mitophagic elimination and their healthy neighbors, the untoward effect of spreading mitochondrial dysfunction throughout the cell, called “mitochondrial contagion” [32] can occur. Indeed, as elaborated below, mitochondrial fusion is governed by specific MFN phosphorylation and ubiquitination events that preclude potentially deleterious fusion between healthy and severely damaged mitochondria [33, 34]. Whether mitochondrial fusion also has specific drivers that tag potential mitochondrial fusion partners for active transport, co-localization, and pairing in an orchestrated manner is unknown. However, if mitochondrial pairing is not purely random, then mitochondrial co-localization via directed transport may actually be the initial permissive event in fusion (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mitofusin involvement in mitochondrial fusion.

Schematic depiction of different steps leading to complete fusion between two healthy mitochondria. The same steps would apply if a healthy individual mitochondrion were joining an interconnected mitochondrial network.

Structural considerations for mitofusin-mediated mitochondria-mitochondria tethering.

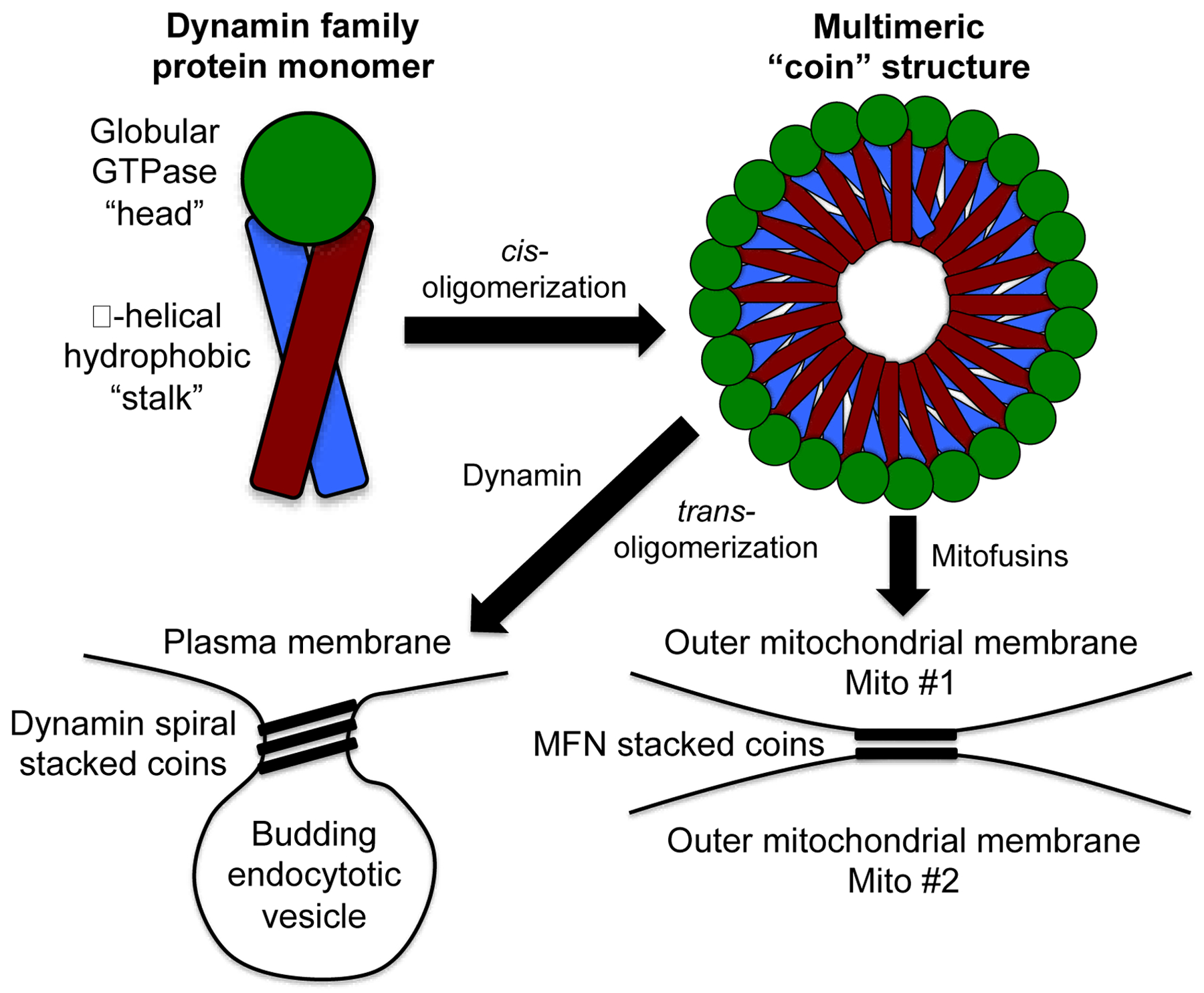

The phenomenology of mitochondrial fusion is understood, but the biophysical events culminating in MFN-mediated outer mitochondrial membrane fusion are still being defined. MFN-mediated tethering events between mitochondria, either for inter-organelle communication by trans-organelle molecular transfer, or that precede mitochondrial fusion, likely require highly organized macromolecular structures. Unfortunately, most schematic depictions of mitochondrial fusion depict single pairs of MFN homo- or hetero-dimers interacting in trans between two mitochondria [35], and only rarely has there been consideration of putative larger structures [36]. One can formulate testable hypotheses about functional mitofusin macromolecular structures from studies of prototypical members of the dynamin family of small GTPases to which mitofusins belong [37]. The structures of dynamin proteins have been described in detail and the relationships between their structures and functions have largely been solved [38]. To the extent that data are available for MFN1 and MFN2, dynamins appear to share with mammalian mitofusins: 1. a similar 3-dimensional structural conformation; 2. the ability to undergo GTP-dependent changes in that structure; 3. a tendency to form homodimers and multimers; and 4. an ability to deform cell membranes. For dynamin, side-by-side cis oligomerization results in a coin-like oligomeric spiral structure that binds in trans (i.e. from one “coin” to the next in the stack), creating a spiral ligature around the neck of plasma membrane invaginations during clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Figure 2). This spiral collar structure constricts to deform the encircled phospholipid membrane, inducing a membrane rupture that spontaneously closes to separate endocytic vesicles from the plasma membrane [39]. Spatiotemporally co-localized membrane rupture also precedes membrane fusion, which becomes the consequence of semi-fluid phospholipid membrane self-repair. For this reason, the same type of processes described for dynamin-mediated excision of endocytotic vesicles could, if the macromolecular structure were a pair of stacked coins on two adjacent mitochondria, evoke organelle membrane fusion (Figure 2). This hypothesis is valid only if the area within MFN toroidal structures is similar to the area within a dynamin spiral structure, i.e. ~2,000 nm2 (based on the reported in vivo diameter of 50 nm [39]). But, while biochemical studies have clearly shown that mitofusins will form multimers as well as dimers [40], these dimensions are inconsistent with a recent detailed ultrastructural study of mitofusin “docking ring” complexes in yeast mitochondria, which form 10-fold larger contact sites (mean area ~23,000 nm2) [41]. By Laplace’s law (wall stress is proportional to internal radius), the larger area (radius) within the ligature would produce greater membrane stress and hence require greater-than-achievable energies to induce a membrane deformation sufficient for rupture. Therefore, it is likely that the large “docking ring” structure represents contact sites for mitochondria-mitochondria communication, and not the final structure leading to outer membrane fusion. Importantly, the same study describes a toroidal pore of 40 nm diameter (i.e. area of ~1,250 nm) within, and seemingly derived from, the larger mitofusin contact structure. This is similar in size to the toroidal structure described for dynamin and could be the site of, and enabling structure for, membrane fusion [41]. Thus, although there are other proteins such as Atlastin that may promote membrane fusion as dimers [42], available direct and inferential evidence seem more consistent with directed mitochondria-mitochondria co-localization, multimeric mitofusin-mediated tethering, formation of large contact and small toroidal fusion sites, and subsequent GTP-dependent membrane fusion.

Figure 2. Possible mitofusin macromolecular tethering structures based on dynamin.

Schematic depiction of different steps leading to complete fusion between two healthy mitochondria. (The same steps would apply if a healthy individual mitochondrion were joining an interconnected mitochondrial network.) At the top are schematic depictions of monomeric and multimeric proteins of the dynamin family, which includes mitofusins. At the bottom are depictions of the typical dynamin structure that deforms plasma membranes during endocytosis (left) and the hypothetical version of this schema as it may apply to mitofusin-mediated mitochondrial tethering and fusion (right). Not to scale.

Definitive structural information for MFN1 and MFN2, alone and in their putative cis- and trans- oligomerized forms, could help validate the above notion. Such data have been difficult to achieve. Biochemical and biophysical studies have suggested either a folded hairpin MFN conformation in which both the amino and carboxyl termini are cytosolic [23, 34, 40, 43], or a linear conformation in which the carboxyl terminus is buried within the organelle [44]. It is possible that both structures exist as MFN1 and MFN2 conformations change to permit mitochondrial tethering and fusion [43]. Thus, mitofusins adopt different structures, depending upon activation state. To date, MFN1 and MFN2 have only been crystalized as a partial proteins comprised of the N-terminal GTPase “head” and the C-terminal “tail”, but lacking part of the intervening “stalk” region [45–48]. Since the stalk region that was removed from the crystalized MFN protein fragments seems necessary for both MFN cis-oligomerization at the mitochondrial outer membrane [41] and MFN conformational changes that induce mitochondrial fusion [34, 35, 43], and because the proper context of MFN-MFN interactions is in membranesrather than in solution, conclusions about MFN structures and structural mechanisms for mitochondria-mitochondria tethering based on protein fragment data need to be evaluated with appropriate caution [49].

MFN-mediated anchoring of mitochondria to transport proteins may contribute to mitochondrial motility.

It is incontrovertible that MFN proteins mediate mitochondrial fusion. Above, I postulated that directed mitochondrial transport might be the initial enabling step of fusion. However, it is not mechanistically clear how MFN1 and MFN2 can affect mitochondrial transport.

In general, mitochondria and other cellular cargo are actively transported along cell microtubular structures by coupling, i.e. anchoring, to the molecular motors, dynein and kinesin. The cytosolic adaptor protein that links cellular cargo to these transport motor proteins is Trak1, the ortholog of Drosophila Milton [50]. Because the Trak1-dynein/kinesin mechanism mediates general cellular transport and is not specific to mitochondria, one or more specific regulators of directed transport should evoke mitochondria-Trak1 interactions. The only mitochondrial resident transport adaptor or anchoring protein currently known is the Mitochondrial Rho GTPase 1 (Miro1), a.k.a. Ras Homolog Family Member T1 (RhoT1). Miro1 sits on the outer mitochondrial membrane protein where it reversibly binds Trak1, depending upon Ca2+ concentrations [51]. Cells that lack Miro1 (but not Miro2) exhibit diminished mitochondrial mobilization [52]. It is thought that mitochondrial Miro1 attaches organelles through the interaction with Trak1 to molecular motors that transport mitochondrial cargo along cell mitocrotubules, and that mitochondria are deposited at locales marked by increased cytosolic calcium [53]. This process seems well tailored for mitochondrial transport to neuronal synapses or areas of injury that require intensive local production of mitochondrial ATP for neurotransmission and repair, respectively. However, it is difficult to understand how the calcium sensing Miro1 mitochondrial transport and delivery mechanism would be involved in mitochondrial fusion.

Observational data suggest that MFN proteins themselves can be important for mitochondrial transport, either by regulating Miro1 or as Miro1-like effectors acting in parallel. Mitochondrial motility is severely depressed in neurons expressing Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A (CMT2A)-causing loss-of-function MFN2 mutants [34, 54, 55]. Indeed, defective mitochondrial transport, in addition to or instead of a pure mitochondrial fusion defect, could explain why this genetic neuropathy preferentially affects long peripheral nerves but spares central nervous and cardiac systems that are equally dependent upon mitochondria: mitochondrial transport defects would manifest first and most severely in cells, such as long peripheral neurons, in which the distances mitochondrial must travel are the greatest. The additional observation that pharmacological mitofusin activation reversed mitochondrial dysmotility caused by mutant MFN2 in CMT2A mouse peripheral nerves [34] indicates that both loss-ofmotility and rescue-of-dysmotilty in CMT2A are mitofusin-specific. Finally, mitofusins can bind to Miro1 when co-expressed, implying either direct MFN-Miro interactions or separate involvement of both proteins in a larger macromolecular mitochondrial transport protein complex [55]. The idea that MFN either directly or indirectly binds to Miro is somewhat controversial because forced combined expression can provoke promiscuous interactions between proteins that do not normally interact. Thus, while inferential evidence suggests that MFN proteins are either facilitators of Miro-mediated anchoringof mitochondria to the transport apparatus, or perhaps themselves serve as mitochondrial anchors, available data are correlative and definitive studies are lacking.

Anchoring of the Parkin-ubiquitination machinery to mitochondria by phospho-MFN2 redirects mitochondrial fusion to mitophagy.

As described above, the contextual links between mitochondrial fusion and mitochondrial transport are obvious: for growth-by-fusion, repair-by-fusion, or simple network remodeling, mitochondria require directed transport and delivery. Here I describe how a third seemingly distinct process, mitophagy, can be orchestrated along with fusion and transport to maintain overall cell health.

From a pathophysiological perspective, fusion is the destiny of individual mitochondria deemed to be either healthy (and therefore suitable for fusion-mediated integration with other members of the mitochondrial collective) or only modestly impaired (such that fusing with other mitochondria could be reparative). For the organelle, fusion equals life. According to this abstraction, the functional opposite of fusion is not fission (its dictionary antonym), but mitophagy, i.e. the selective removal from the cell of severely damaged mitochondria. Early reports that mitofusins are ubiquitinated by the Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase and targeted for proteasomal degradation during mitophagy [56] [57–62] uncovered a reciprocal relationship between mitochondrial fusion and mitophagy [63]. The idea was that ubiquitination and degradation of Mfn1 and Mfn2 would impede fusion of organelles targeted for mitophagy, but there are two concerns. First, Parkin ubiquitinates large numbers of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins, of which mitofusins are just two [64]. Thus, Parkin-mediated MFN ubiquitination is part of a generalized mitophagy-enabling process rather than a specific mechanism that interrupts mitochondrial fusion. Second, selective proteasomal degradation of ubiquitinated mitofusins is a cumbersome and energy-requiring process that may take almost as long or longer than autophagosome recruitment. In this case, MFN ubiquitination would not be very effective at interdicting fusion of mitochondria waiting to be engulfed by autophagosomes, and other (more rapid) mechanisms need to be considered

Results of in vivo Mfn1 and Mfn2 gene deletion, individually and in combination and in multiple organ systems, support mitofusin regulation of mitophagy. Combined Mfn1 and Mfn2 ablation in mouse skeletal muscle caused accumulation of abnormal mitochondria in skeletal myocytes, resulting in pathologically increased levels of mitochondrial genome mutations [65]. The analogous conditional combined Mfn1 and Mfn2 ablation experiment in mouse hearts resulted in increased numbers of abnormal mitochondria, which was mechanistically linked to impaired mitophagy [66, 67]. The obvious conclusion from these cardiac- and skeletal muscle Mfn1/Mfn2 double KO studies is that mitochondrial tethering and fusion are essential to maintaining mitochondrial fitness, and therefore to prevent mitophagy. By this reasoning, genetic interruption of mitochondrial fusion impedes mitochondrial renewal and incites a generalized deterioration in mitochondrial fitness that can overwhelm normal mitophagic quality control. This may not be correct.

The tacit underlying assumption with the above interpretation is that mitofusins function exclusively as fusion proteins, i.e. that the only direct consequence of genetically ablating both mitofusins is to interrupt mitochondrial fusion. This type of mistake is common in mouse gene knockout experiments, derived from an understandable tendency of researchers to reduce complex biological systems to simple concepts such as “one protein, one purpose”. In the case of mitofusins, however, the results obtained from early studies of cardiac- and neuron-specific Mfn2 (only) knockout mice indicated that Mfn2 deletion (with retention of Mfn1 and therefore continued, if diminished, mitochondrial fusion) directly impaired Parkin-mediated mitophagy and compromised mitochondrial fitness [33, 68, 69]. In striking contrast, the analogous Mfn1 only knockouts were well tolerated and did not evidently perturb mitophagy.

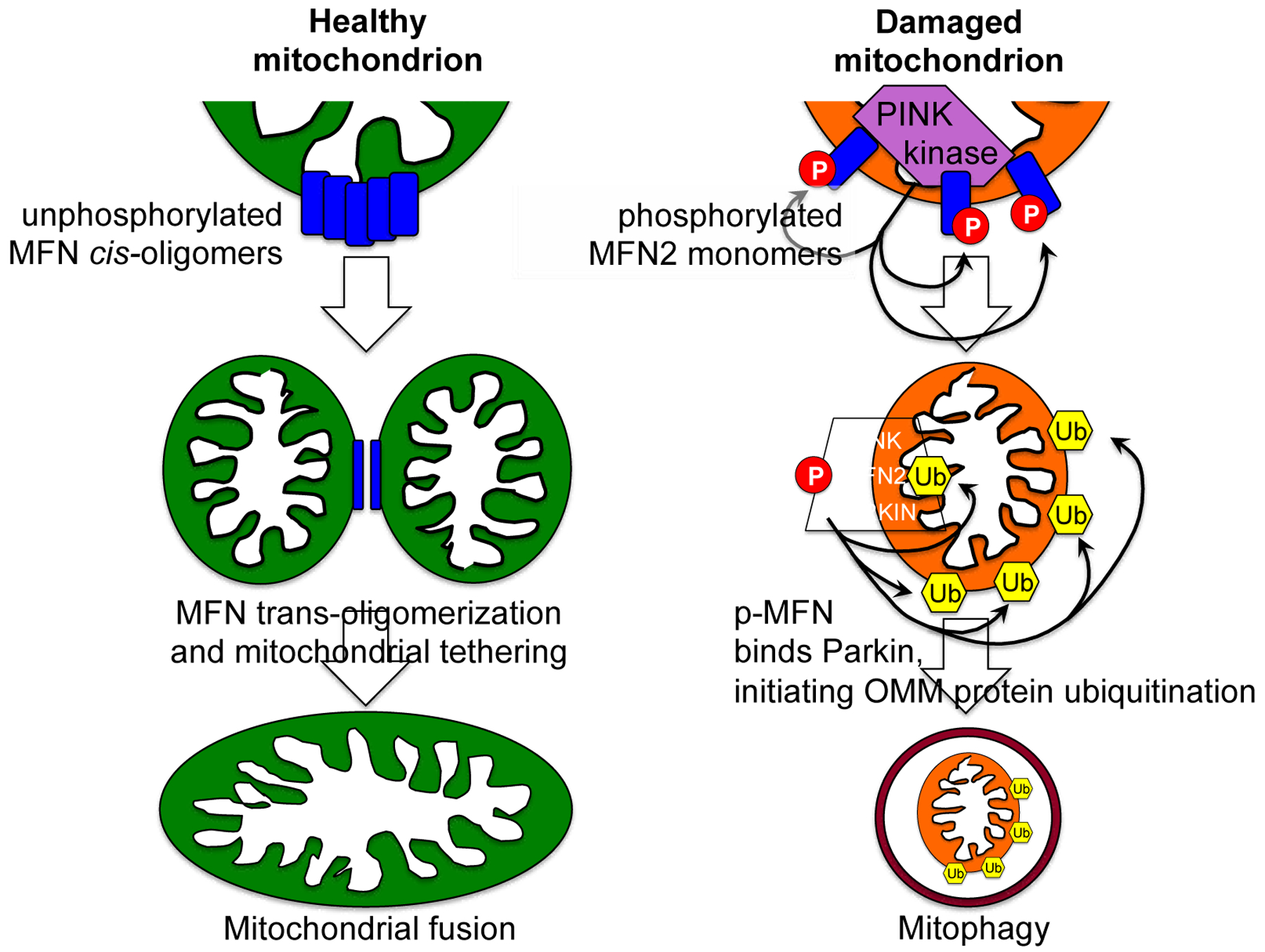

The mechanism for impaired mitophagy after Mfn2 gene deletion was discovered when phosphorylation of MFN2 by PINK1 kinase, the upstream activator of Parkin-mediated mitophagy, was shown to convert Mfn2 from an MFN-binding protein to a Parkin-binding protein [33]: Nuclear-encoded PINK1 kinase localizes to and is imported by mitochondria. Healthy mitochondria actively and immediately degrade PINK1, such that the normal state is for little or no PINK1 to be present (much like a PINK1 “knockout”). However, damaged or functionally-impaired mitochondria don’t degrade PINK1, allowing it to accumulate and phosphorylate its many substrates, including Parkin, ubiquitin [70], and MFN2 [33, 34]. Three PINK1 phosphorylation sites on human MFN2 (T111, S378, S442) have been identified, validated by mass spectrometry, and functionally interrogated through site-directed mutagenesis [33, 34]. Phosphorylation at all three of these sites suppresses mitochondrial fusion, and while phosphorylation of two (T111 and S442) promotes MFN2-Parkin binding. Thus, MFN2 phosphorylation by PINK1 accumulating in damaged mitochondria simultaneously initiates mitophagy by becoming an outer mitochondrial membrane anchor protein for cytosolic Parkin, and quarantines the damaged organelle by preventing mitochondrial fusion. In essence, MFN2 phosphorylation by PINK1 redirects its binding partners from other MFNs to Parkin, which redirects mitochondrial fate from survival to mitophagic elimination (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Phosphorylation of MFN2 by PINK1 kinase determines mitochondrial fate by changing its interaction partners.

On the left is a schematic depiction of unphosphorylated mitofusin promoting healthy mitochondrial tethering and fusion, as in Figure 1. On the right is a depiction of a damaged mitochondrion in which PINK1 kinase accumulates, activating Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Only events that directly impact mitofusins are shown. Encircled P indicates phosphorylation. Ub inside hexagon indicated ubiquitination.

The role of PINK1-Parkin mitophagy, and of intermediary MFN2 as a PINK1 substrate that becomes a mitochondrial Parkin-binding protein, likely varies in different tissue types and organ systems. Because mutations in the genes encoding PINK1 and Parkin cause juvenile-onset Parkinson’s disease, it is widely assumed that impaired PINK1-Parkin mediated mitochondrial quality control underlies observed neuropathology in this syndrome [71]. However, this has been difficult to nail down and may represent only one facet of a more complicated pathophysiology [72, 73]. For example, in adult hearts the PINK1-Parkin mitophagy pathway appears to play a minor role in homeostatic mitochondrial quality control and other mitophagy mechanisms shoulder the burden of maintaining basal mitochondrial fitness [74, 75]. In hearts, PINK1-Parkin mediated mitophagy is induced in response to myocardial injury [63, 76]. By contrast, in early perinatal hearts the PINK1-MFN2-Parkin mitophagy pathway plays a unique and critical developmental role by promoting general mitochondrial turnover as part of the well-described myocardial transition in substrate preference from carbohydrates to fatty acids [77–79]. When this developmental transition is interrupted, either by cardiomyocyte-specific Parkin deletion or by expressing MFN2 mutants that cannot be phosphorylated by PINK1 at the amino acids required for Parkin binding, mitochondrial metabolic maturation does not occur and the resulting mismatch of fetal metabolism in postnatal hearts proves lethal [79].

MFN2 is a mitochondrial-ER tether.

The original description of a mitochondrial tethering event distinct from mitochondrial fusion was of MFN2 forming mitochondrial connections with endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [22, 80]. The phenomenological evidence supporting the idea that MFN2 is a major (but not the only [81–83]) protein tether linking mitochondria to ER/SR is substantial, perhaps incontrovertible. Both MFN1 and MFN2 localize to outer mitochondrial membranes, whereas a small proportion of MFN2 is located at ER membranes. ER-localized MFN2 can interact with mitochondrial MFN1 or MFN2 to tether the two organelles. The consequences of such tethering, i.e. whether MFN2 narrows the gap between mitochondria and SR to form functional calcium microdomains [22, 84–86], or fixes the gap at a distance sufficiently great that it can actually impair ER-mitochondrial Ca2+ transport [87, 88], have emerged as a matter of some controversy. The preponderance of evidence, including studies of MFN2 null cardiac myocytes [84, 89], supports a positive effect of MFN2 on ER/SR-mitochondrial calcium signaling.

As introduced above, conditional MFN2 gene ablation revealed complex biological consequences of MFN2-mediated mitochondria-ER calcium cross-talk. One hypothesis suggests that the intimate association between mitochondria and ER (or in hearts, SR) is deleterious because it facilitates mitochondrial calcium uptake that can induce mitochondrial permeability pore transitioning [90, 91] and trigger mitochondrial rupture that, if it is widespread, will cause cell death. According to this proposition, removal of the tether by genetically deleting MFN2 should provide resistance to cell death, which has been described by some groups who observed that cardiomyocyte-specific Mfn2 or Mfn1/Mfn2 deletion conferred resistance to myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury [92, 93]. However, other investigators have not detected altered mitochondrial permeability transition pore function [94], or have even reported increased ischemia-reperfusion injury induced by cardiac Mfn2 deficiency [95].

A counter-hypothesis holds that mitochondrial sensing of ER/SR calcium release through tethered microdomains is beneficial, enabling mitochondria to anticipate increased metabolic demand and preemptively enhance respiratory enzyme functionality during periods of transiently increased workload [96, 97]. This paradigm predicts that genetic removal of the MFN2 mitochondria-ER/SR tether should delay metabolic responses to increased demand. Indeed, this result has been observed in cardiac-specific Mfn2 knockout mice [84]. Thus, published reports are consistent with the idea that Mfn2-mediated ER-mitochondria contacts both sensitize injured cardiac myocytes to mitochondria-mediated cell death under conditions of calcium overload, and protect cardiac myocytes in normal hearts from metabolic deficits evoked by acute increases in work. It seems likely that both mechanisms are operative, and that the normal function of Mfn2-mediated mitochondria-SR contact sites in cardiac myocytes is to create focal microdomains within which calcium and other small molecules are protected from cytoplasmic diffusion and therefore efficiently transferred between organelles. However, under conditions such as myocardial reperfusion injury wherein ER/SR calcium release is abnormally high, the same microdomain tethering increases sensitivity of mitochondria to apoptotic and necroptotic stimuli. In tissues that (unlike myocardium) have significant regenerative capacity, removal of seriously damaged cells is an essential part of normal repair. Accordingly, in such tissues a mechanism to sense critical cellular injury and initiate programmed cell death that contains and removes damaged cells is not detrimental. Adverse consequences accrue only in tissues where it is ultimately better for the organ to retain damaged cells because they cannot be replaced.

Some observations and speculations about the role of MFN2 mutations and mitochondrial tethering in human disease.

A common theme emerging from studies of mitofusin-mediated anchoring of other proteins and of tethering to other mitochondria or different organelles is that mitofusins coordinate multiple mitochondrial processes that facilitate homeostatic interactions with their host cells. For example, it was recently reported that the PINK1-Parkin mitophagy mechanism directly regulates mitofusin-mediated mitochondria-ER tethering essential to microdomain-dependent inter-organelle calcium cross-talk [98]. Parkin-mediated ubiquitination of Mfn2 induced disassembly of macromolecular tethering complexes, causing dissociation of mitochondria from ER. This Parkin-induced separation of ER from mitochondria targeted for mitophagy pathway echoes separation of mitochondria from each other through PINK1-mediated suppression of mitochondrial fusion [33]. In both instances, mitochondria-specific activation of the PINK1-Parkin mitophagy pathway physically and functionally sequesters damaged organelles until they are removed by cellular autophagosome/lysosome machinery, thus preventing mitochondrial contagion.

Because MFN1 and MFN2 are expressed in normal mitochondria, mitofusins are ubiquitous in all mammalian cells except spermatozoa. Gene ablation studies show that both mitofusins are essential to normal embryonic development [99], and deletion of Mfn1 and Mfn2 from primordial cardiac myocytes early in heart development (using Nkx-2.5 Cre in combination with floxed alleles) impaired cardiomyoyte differentiation and proliferation, resulting in thin-walled fetal hearts and non-viable embryos [100]. Likewise, tissue-specific ablation of Mfn1 and Mfn2 from the neurological system and skeletal muscle caused severe pathology linked to mitochondrial dysfunction [65, 101]. Based on these data it might be predicted that damaging loss-of-function mutations in human MFN1 and MFN2 would cause a plethora of multi-system diseases. That seems not to be the case, at least at the level of genetic resolution achieved by current technologies.

There are currently no reports of MFN1 mutations linked to human disease (https://omim.org). By contrast, MFN2 mutations cause the autosomal dominant sensory/motor peripheral neuropathy Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease Type 2A [102, 103]. Homozygous or compound heterozygous MFN2 mutations have also been identified in very rare cases of multiple symmetric lipomatosis (MSL) ([104, 105]). CMT2A and MSL are heritable genetic conditions in which systemic mono-allelic (heterozygous) dominant inhibitory (CMT2A) or bi-allelic (compound heterozygous or homozygous) MFN2 mutations cause disease that manifests predominantly in one tissue. Thus, a disparity exists between the apparent biological importance of mitofusins established in genetic mouse models and the absence of life-threatening clinical disease in human patients carrying dysfunctional genetic mitofusin mutations.

These observations raise the question of why there aren’t quantitatively more, and qualitatively more severe, human diseases linked to MFN2 (and MFN1) dysfunction. The answer is unknown, but it is reasonable to posit that MFN2 can function in critical ways that MFN1 does not, that impairment of these MFN2 functions cannot be compensated for by MFN1, and that these functions are more important in the tissues affected by clinical MFN2 mutations. Mitochondrial tethering to ER/SR, which is specific on the ER/SR side for MFN2, must be considered in this context. Transmission and amplification of PINK1-Parkin mitophagy signaling is also a candidate MFN2-specific pathway.

There is another intriguing (and testable) possibility: patients with CMT2A and MSL are the survivors, representing only a fraction of the population with damaging MFN2 mutations, and the majority of MFN2 mutation carriers succumbed in utero or early in childhood. The corollary to this proposition is that the MFN2 mutations in CMT2A and MSL have limited adverse effects and other more damaging mutations result (like MFN knockout mice) in fetal or early perinatal lethality. Because they do not survive, such individuals do not appear in adult genomic databases. In support of this notion, the GTPase domain of MFN2 is a hot spot for mutations that cause CMT2A, but mutations of the single lysine critical for MFN GTPase activity (in mice it is Lys 109, which has been artificially mutated to Ala with devastating effects on MFN function) have not been detected. This suggests that negative selection may be occurring. Although there are no causal human genetic data to prove negative selection, inferential data are abundant within the large genomic databases and absence of direct data does not disprove the hypothesis. Given severe cardiac and skeletal muscle abnormalities in MFN knockout mice, it would seem worthwhile to interrogate instances of very early cardiac and skeletal myopathies for MFN2 (and MFN1) mutations, especially those mysterious cases with systemic metabolic abnormalities. Such an effort would require a consortium of University based Children’s Hospitals and could be integrated into larger efforts applying advanced genomic techniques to the broader problem of perinatal myopathy and neuropathy.

Highlights.

Mitofusin multifunctionality is linked to context-specific interactions with multiple molecular partners.

Mitofusins tethering of mitochondria to each other and to reticulum mediates organelle communications.

Mitofusin anchoring of Parkin to outer mitochondrial membranes initiates and/or amplifies PINK1-Parkin mitophagy.

Mitofusins are implicated in mitochondrial motility, but the mechanism is unknown.

Acknowledgements

Funding: Supported by NIH R35135736. GWD is the Philip and Sima K. Needleman-endowed Professor at Washington University in St. Louis and a Scholar-Innovator awardee of the Harrington Discovery Institute.

Footnotes

Competing interests: G.W.D. is an inventor on patent applications PCT/US18/028514 submitted by Washington University and PCT/US19/46356 submitted by Mitochondria Emotion, Inc that cover the use of small molecule mitofusin agonists to treat chronic neurodegenerative diseases, and is the founder of Mitochondria in Motion, Inc., a Saint Louis based biotech R&D company focused on enhancing mitochondrial trafficking and fitness in neurodegenerative diseases.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Gray MW, Burger G, Lang BF, Mitochondrial evolution, Science 283(5407) (1999) 1476–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dyall SD, Brown MT, Johnson PJ, Ancient invasions: from endosymbionts to organelles, Science 304(5668) (2004) 253–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Timmis JN, Ayliffe MA, Huang CY, Martin W, Endosymbiotic gene transfer: organelle genomes forge eukaryotic chromosomes, Nat Rev Genet 5(2) (2004) 123–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bonifacino JS, Vesicular transport earns a Nobel, Trends Cell Biol. 24(1) (2014) 3–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sugiura A, McLelland GL, Fon EA, McBride HM, A new pathway for mitochondrial quality control: mitochondrial-derived vesicles, EMBO J. 33(19) (2014) 2142–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bernhard W, Haguenau F, Gautier A, Oberling C, [Submicroscopical structure of cytoplasmic basophils in the liver, pancreas and salivary gland; study of ultrafine slices by electron microscope], Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat 37(3) (1952) 281–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bernhard W, Rouiller C, Microbodies and the problem of mitochondrial regeneration in liver cells, J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol 2(4 Suppl) (1956) 355–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vance JE, Phospholipid synthesis in a membrane fraction associated with mitochondria, J. Biol. Chem 265(13) (1990) 7248–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Vance JE, Newly made phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine are preferentially translocated between rat liver mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum, J. Biol. Chem 266(1) (1991) 89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rizzuto R, Pinton P, Carrington W, Fay FS, Fogarty KE, Lifshitz LM, et al. , Close contacts with the endoplasmic reticulum as determinants of mitochondrial Ca2+ responses, Science 280(5370) (1998) 1763–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cardenas C, Miller RA, Smith I, Bui T, Molgo J, Muller M, et al. , Essential regulation of cell bioenergetics by constitutive InsP3 receptor Ca2+ transfer to mitochondria, Cell 142(2) (2010) 270–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Patergnani S, Suski JM, Agnoletto C, Bononi A, Bonora M, De Marchi E, et al. , Calcium signaling around Mitochondria Associated Membranes (MAMs), Cell Commun Signal 9 (2011) 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pinton P, Giorgi C, Siviero R, Zecchini E, Rizzuto R, Calcium and apoptosis: ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer in the control of apoptosis, Oncogene 27(50) (2008) 6407–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S, Calcium and cell death mechanisms: a perspective from the cell death community, Cell Calcium 50(3) (2011) 211–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Orrenius S, Gogvadze V, Zhivotovsky B, Calcium and mitochondria in the regulation of cell death, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 460(1) (2015) 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Prudent J, McBride HM, The mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum contact sites: a signalling platform for cell death, Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 47 (2017) 52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fonteriz R, Matesanz-Isabel J, Arias-Del-Val J, Alvarez-Illera P, Montero M, Alvarez J, Modulation of Calcium Entry by Mitochondria, Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 898 (2016) 405–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].De Stefani D, Rizzuto R, Pozzan T, Enjoy the Trip: Calcium in Mitochondria Back and Forth, Annu. Rev. Biochem 85 (2016) 161–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rizzuto R, Brini M, Murgia M, Pozzan T, Microdomains with high Ca2+ close to IP3-sensitive channels that are sensed by neighboring mitochondria, Science 262(5134) (1993) 744–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Achleitner G, Gaigg B, Krasser A, Kainersdorfer E, Kohlwein SD, Perktold A, et al. , Association between the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria of yeast facilitates interorganelle transport of phospholipids through membrane contact, Eur. J. Biochem 264(2) (1999) 545–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Csordas G, Renken C, Varnai P, Walter L, Weaver D, Buttle KF, et al. , Structural and functional features and significance of the physical linkage between ER and mitochondria, J. Cell Biol 174(7) (2006) 915–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].de Brito OM, Scorrano L, Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria, Nature 456(7222) (2008) 605–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Koshiba T, Detmer SA, Kaiser JT, Chen H, McCaffery JM, Chan DC, Structural basis of mitochondrial tethering by mitofusin complexes, Science 305(5685) (2004) 858–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chan DC, Fusion and fission: interlinked processes critical for mitochondrial health, Annu. Rev. Genet 46 (2012) 265–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mattie S, Krols M, McBride HM, The enigma of an interconnected mitochondrial reticulum: new insights into mitochondrial fusion, Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 59 (2019) 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chen H, Chan DC, Emerging functions of mammalian mitochondrial fusion and fission, Hum. Mol. Genet 14 Spec No. 2 (2005) R283–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Detmer SA, Chan DC, Complementation between mouse Mfn1 and Mfn2 protects mitochondrial fusion defects caused by CMT2A disease mutations, J. Cell Biol 176(4) (2007) 405–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Shirihai OS, Song M, Dorn GW 2nd, How mitochondrial dynamism orchestrates mitophagy, Circ. Res 116(11) (2015) 1835–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Song M, Dorn GW 2nd, Mitoconfusion: noncanonical functioning of dynamism factors in static mitochondria of the heart, Cell Metab. 21(2) (2015) 195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Youle RJ, van der Bliek AM, Mitochondrial fission, fusion, and stress, Science 337(6098) (2012) 1062–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Schon EA, Gilkerson RW, Functional complementation of mitochondrial DNAs: mobilizing mitochondrial genetics against dysfunction, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1800(3) (2010) 245–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bhandari P, Song M, Chen Y, Burelle Y, Dorn GW 2nd, Mitochondrial contagion induced by Parkin deficiency in Drosophila hearts and its containment by suppressing mitofusin, Circ. Res 114(2) (2014) 257–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Chen Y, Dorn GW 2nd, PINK1-phosphorylated mitofusin 2 is a Parkin receptor for culling damaged mitochondria, Science 340(6131) (2013) 471–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rocha AG, Franco A, Krezel AM, Rumsey JM, Alberti JM, Knight WC, et al. , MFN2 agonists reverse mitochondrial defects in preclinical models of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A, Science 360(6386) (2018) 336–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Knott AB, Perkins G, Schwarzenbacher R, Bossy-Wetzel E, Mitochondrial fragmentation in neurodegeneration, Nat. Rev. Neurosci 9(7) (2008) 505–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Dorn GW 2nd, Evolving Concepts of Mitochondrial Dynamics, Annu. Rev. Physiol 81 (2019) 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Low HH, Lowe J, A bacterial dynamin-like protein, Nature 444(7120) (2006) 766–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Low HH, Sachse C, Amos LA, Lowe J, Structure of a bacterial dynamin-like protein lipid tube provides a mechanism for assembly and membrane curving, Cell 139(7) (2009) 1342–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Morlot S, Roux A, Mechanics of dynamin-mediated membrane fission, Annu Rev Biophys 42 (2013) 629–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Sloat SR, Whitley BN, Engelhart EA, Hoppins S, Identification of a mitofusin specificity region that confers unique activities to Mfn1 and Mfn2, Mol. Biol. Cell 30(17) (2019) 2309–2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Brandt T, Cavellini L, Kuhlbrandt W, Cohen MM, A mitofusin-dependent docking ring complex triggers mitochondrial fusion in vitro, Elife 5 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Moss TJ, Andreazza C, Verma A, Daga A, McNew JA, Membrane fusion by the GTPase atlastin requires a conserved C-terminal cytoplasmic tail and dimerization through the middle domain, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108(27) (2011) 11133–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Franco A, Kitsis RN, Fleischer JA, Gavathiotis E, Kornfeld OS, Gong G, et al. , Correcting mitochondrial fusion by manipulating mitofusin conformations, Nature 540(7631) (2016) 74–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mattie S, Riemer J, Wideman JG, McBride HM, A new mitofusin topology places the redox-regulated C terminus in the mitochondrial intermembrane space, J. Cell Biol 217(2) (2018) 507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Qi Y, Yan L, Yu C, Guo X, Zhou X, Hu X, et al. , Structures of human mitofusin 1 provide insight into mitochondrial tethering, J. Cell Biol 215(5) (2016) 621–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Cao YL, Meng S, Chen Y, Feng JX, Gu DD, Yu B, et al. , MFN1 structures reveal nucleotide-triggered dimerization critical for mitochondrial fusion, Nature 542(7641) (2017) 372–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Yan L, Qi Y, Huang X, Yu C, Lan L, Guo X, et al. , Structural basis for GTP hydrolysis and conformational change of MFN1 in mediating membrane fusion, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 25(3) (2018) 233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Li YJ, Cao YL, Feng JX, Qi Y, Meng S, Yang JF, et al. , Structural insights of human mitofusin-2 into mitochondrial fusion and CMT2A onset, Nat Commun 10(1) (2019) 4914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Low HH, Lowe J, Dynamin architecture--from monomer to polymer, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 20(6) (2010) 791–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Stowers RS, Megeath LJ, Gorska-Andrzejak J, Meinertzhagen IA, Schwarz TL, Axonal transport of mitochondria to synapses depends on milton, a novel Drosophila protein, Neuron 36(6) (2002) 1063–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Wang X, Schwarz TL, The mechanism of Ca2+ -dependent regulation of kinesin-mediated mitochondrial motility, Cell 136(1) (2009) 163–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lopez-Domenech G, Covill-Cooke C, Ivankovic D, Halff EF, Sheehan DF, Norkett R, et al. , Miro proteins coordinate microtubule- and actin-dependent mitochondrial transport and distribution, EMBO J. 37(3) (2018) 321–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Devine MJ, Birsa N, Kittler JT, Miro sculpts mitochondrial dynamics in neuronal health and disease, Neurobiol. Dis 90 (2016) 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Baloh RH, Schmidt RE, Pestronk A, Milbrandt J, Altered axonal mitochondrial transport in the pathogenesis of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease from mitofusin 2 mutations, J. Neurosci 27(2) (2007) 422–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Misko A, Jiang S, Wegorzewska I, Milbrandt J, Baloh RH, Mitofusin 2 is necessary for transport of axonal mitochondria and interacts with the Miro/Milton complex, J. Neurosci 30(12) (2010) 4232–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Pickrell AM, Huang CH, Kennedy SR, Ordureau A, Sideris DP, Hoekstra JG, et al. , Endogenous Parkin Preserves Dopaminergic Substantia Nigral Neurons following Mitochondrial DNA Mutagenic Stress, Neuron 87(2) (2015) 371–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ziviani E, Tao RN, Whitworth AJ, Drosophila parkin requires PINK1 for mitochondrial translocation and ubiquitinates mitofusin, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107(11) (2010) 5018–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Poole AC, Thomas RE, Yu S, Vincow ES, Pallanck L, The mitochondrial fusion-promoting factor mitofusin is a substrate of the PINK1/parkin pathway, PLoS One 5(4) (2010) e10054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Gegg ME, Cooper JM, Chau KY, Rojo M, Schapira AH, Taanman JW, Mitofusin 1 and mitofusin 2 are ubiquitinated in a PINK1/parkin-dependent manner upon induction of mitophagy, Hum. Mol. Genet 19(24) (2010) 4861–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Tanaka A, Cleland MM, Xu S, Narendra DP, Suen DF, Karbowski M, et al. , Proteasome and p97 mediate mitophagy and degradation of mitofusins induced by Parkin, J. Cell Biol 191(7) (2010) 1367–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Glauser L, Sonnay S, Stafa K, Moore DJ, Parkin promotes the ubiquitination and degradation of the mitochondrial fusion factor mitofusin 1, J. Neurochem 118(4) (2011) 636–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Rakovic A, Grunewald A, Kottwitz J, Bruggemann N, Pramstaller PP, Lohmann K, et al. , Mutations in PINK1 and Parkin impair ubiquitination of Mitofusins in human fibroblasts, PLoS One 6(3) (2011) e16746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Dorn GW 2nd, Central Parkin: The evolving role of Parkin in the heart, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1857(8) (2016) 1307–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Sarraf SA, Raman M, Guarani-Pereira V, Sowa ME, Huttlin EL, Gygi SP, et al. , Landscape of the PARKIN-dependent ubiquitylome in response to mitochondrial depolarization, Nature 496(7445) (2013) 372–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Chen H, Vermulst M, Wang YE, Chomyn A, Prolla TA, McCaffery JM, et al. , Mitochondrial fusion is required for mtDNA stability in skeletal muscle and tolerance of mtDNA mutations, Cell 141(2) (2010) 280–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Song M, Mihara K, Chen Y, Scorrano L, Dorn GW 2nd, Mitochondrial fission and fusion factors reciprocally orchestrate mitophagic culling in mouse hearts and cultured fibroblasts, Cell Metab. 21(2) (2015) 273–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Song M, Franco A, Fleischer JA, Zhang L, Dorn GW 2nd, Abrogating Mitochondrial Dynamics in Mouse Hearts Accelerates Mitochondrial Senescence, Cell Metab. 26(6) (2017) 872–883.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Lee S, Sterky FH, Mourier A, Terzioglu M, Cullheim S, Olson L, et al. , Mitofusin 2 is necessary for striatal axonal projections of midbrain dopamine neurons, Hum. Mol. Genet 21(22) (2012) 4827–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Chen Y, Sparks M, Bhandari P, Matkovich SJ, Dorn GW 2nd, Mitochondrial genome linearization is a causative factor for cardiomyopathy in mice and Drosophila, Antioxid Redox Signal 21(14) (2014) 1949–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Pickles S, Vigie P, Youle RJ, Mitophagy and Quality Control Mechanisms in Mitochondrial Maintenance, Curr. Biol 28(4) (2018) R170–r185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Pickrell AM, Youle RJ, The roles of PINK1, parkin, and mitochondrial fidelity in Parkinson’s disease, Neuron 85(2) (2015) 257–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Corti O, Lesage S, Brice A, What genetics tells us about the causes and mechanisms of Parkinson’s disease, Physiol. Rev 91(4) (2011) 1161–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Lee Y, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Animal models of Parkinson’s disease: vertebrate genetics, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 2(10) (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Song M, Gong G, Burelle Y, Gustafsson AB, Kitsis RN, Matkovich SJ, et al. , Interdependence of Parkin-Mediated Mitophagy and Mitochondrial Fission in Adult Mouse Hearts, Circ. Res 117(4) (2015) 346–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Hammerling BC, Najor RH, Cortez MQ, Shires SE, Leon LJ, Gonzalez ER, et al. , A Rab5 endosomal pathway mediates Parkin-dependent mitochondrial clearance, Nat Commun 8 (2017) 14050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Gustafsson AB, Dorn GW 2nd, Evolving and Expanding the Roles of Mitophagy as a Homeostatic and Pathogenic Process, Physiol. Rev 99(1) (2019) 853–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Lopaschuk GD, Collins-Nakai RL, Itoi T, Developmental changes in energy substrate use by the heart, Cardiovasc. Res 26(12) (1992) 1172–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Stanley WC, Recchia FA, Lopaschuk GD, Myocardial substrate metabolism in the normal and failing heart, Physiol. Rev 85(3) (2005) 1093–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Gong G, Song M, Csordas G, Kelly DP, Matkovich SJ, Dorn GW 2nd, Parkin-mediated mitophagy directs perinatal cardiac metabolic maturation in mice, Science 350(6265) (2015) aad2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Dorn GW 2nd, Song M, Walsh K, Functional implications of mitofusin 2-mediated mitochondrial-SR tethering, J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 78 (2015) 123–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Wu S, Lu Q, Wang Q, Ding Y, Ma Z, Mao X, et al. , Binding of FUN14 Domain Containing 1 With Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Receptor in Mitochondria-Associated Endoplasmic Reticulum Membranes Maintains Mitochondrial Dynamics and Function in Hearts in Vivo, Circulation 136(23) (2017) 2248–2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Csordas G, Weaver D, Hajnoczky G, Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondrial Contactology: Structure and Signaling Functions, Trends Cell Biol. 28(7) (2018) 523–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Gordaliza-Alaguero I, Canto C, Zorzano A, Metabolic implications of organellemitochondria communication, EMBO Rep 20(9) (2019) e47928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Chen Y, Csordas G, Jowdy C, Schneider TG, Csordas N, Wang W, et al. , Mitofusin 2-containing mitochondrial-reticular microdomains direct rapid cardiomyocyte bioenergetic responses via interorganelle Ca(2+) crosstalk, Circ. Res 111(7) (2012) 863–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Naon D, Zaninello M, Giacomello M, Varanita T, Grespi F, Lakshminaranayan S, et al. , Critical reappraisal confirms that Mitofusin 2 is an endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria tether, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113(40) (2016) 11249–11254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Beikoghli Kalkhoran S, Hall AR, White IJ, Cooper J, Fan Q, Ong SB, et al. , Assessing the effects of mitofusin 2 deficiency in the adult heart using 3D electron tomography, Physiol Rep 5(17) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Filadi R, Greotti E, Turacchio G, Luini A, Pozzan T, Pizzo P, Mitofusin 2 ablation increases endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112(17) (2015) E2174–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Leal NS, Schreiner B, Pinho CM, Filadi R, Wiehager B, Karlstrom H, et al. , Mitofusin-2 knockdown increases ER-mitochondria contact and decreases amyloid beta-peptide production, J. Cell. Mol. Med 20(9) (2016) 1686–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Papanicolaou KN, Kikuchi R, Ngoh GA, Coughlan KA, Dominguez I, Stanley WC, et al. , Mitofusins 1 and 2 are essential for postnatal metabolic remodeling in heart, Circ. Res 111(8) (2012) 1012–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Halestrap AP, What is the mitochondrial permeability transition pore?, J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 46(6) (2009) 821–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Lemasters JJ, Theruvath TP, Zhong Z, Nieminen AL, Mitochondrial calcium and the permeability transition in cell death, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787(11) (2009) 1395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Papanicolaou KN, Khairallah RJ, Ngoh GA, Chikando A, Luptak I, O’Shea KM, et al. , Mitofusin-2 maintains mitochondrial structure and contributes to stress-induced permeability transition in cardiac myocytes, Mol. Cell. Biol 31(6) (2011) 1309–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Hall AR, Burke N, Dongworth RK, Kalkhoran SB, Dyson A, Vicencio JM, et al. , Hearts deficient in both Mfn1 and Mfn2 are protected against acute myocardial infarction, Cell Death Dis. 7 (2016) e2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Song M, Chen Y, Gong G, Murphy E, Rabinovitch PS, Dorn GW 2nd, Super-suppression of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species signaling impairs compensatory autophagy in primary mitophagic cardiomyopathy, Circ. Res 115(3) (2014) 348–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Zhao T, Huang X, Han L, Wang X, Cheng H, Zhao Y, et al. , Central role of mitofusin 2 in autophagosome-lysosome fusion in cardiomyocytes, J. Biol. Chem 287(28) (2012) 23615–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Maack C, Cortassa S, Aon MA, Ganesan AN, Liu T, O’Rourke B, Elevated cytosolic Na+ decreases mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake during excitation-contraction coupling and impairs energetic adaptation in cardiac myocytes, Circ. Res 99(2) (2006) 172–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Arrieta A, Blackwood EA, Stauffer WT, Glembotski CC, Integrating ER and Mitochondrial Proteostasis in the Healthy and Diseased Heart, Front Cardiovasc Med 6 (2019) 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].McLelland GL, Goiran T, Yi W, Dorval G, Chen CX, Lauinger ND, et al. , Mfn2 ubiquitination by PINK1/parkin gates the p97-dependent release of ER from mitochondria to drive mitophagy, Elife 7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Chen H, Detmer SA, Ewald AJ, Griffin EE, Fraser SE, Chan DC, Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development, J. Cell Biol 160(2) (2003) 189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Kasahara A, Cipolat S, Chen Y, Dorn GW 2nd, Scorrano L, Mitochondrial fusion directs cardiomyocyte differentiation via calcineurin and Notch signaling, Science 342(6159) (2013) 734–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Chen H, McCaffery JM, Chan DC, Mitochondrial fusion protects against neurodegeneration in the cerebellum, Cell 130(3) (2007) 548–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Zuchner S, Mersiyanova IV, Muglia M, Bissar-Tadmouri N, Rochelle J, Dadali EL, et al. , Mutations in the mitochondrial GTPase mitofusin 2 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2A, Nat. Genet 36(5) (2004) 449–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Bombelli F, Stojkovic T, Dubourg O, Echaniz-Laguna A, Tardieu S, Larcher K, et al. , Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A: from typical to rare phenotypic and genotypic features, JAMA Neurol 71(8) (2014) 1036–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Sawyer SL, Cheuk-Him Ng A, Innes AM, Wagner JD, Dyment DA, Tetreault M, et al. , Homozygous mutations in MFN2 cause multiple symmetric lipomatosis associated with neuropathy, Hum. Mol. Genet 24(18) (2015) 5109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Rocha N, Bulger DA, Frontini A, Titheradge H, Gribsholt SB, Knox R, et al. , Human biallelic MFN2 mutations induce mitochondrial dysfunction, upper body adipose hyperplasia, and suppression of leptin expression, Elife 6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]