A 56-year-old African American male with ischemic cardiomyopathy and chronic kidney disease who underwent heart transplantation over 1 year before presentation was admitted to our institution with dry cough, myalgias, and diarrhea concerning for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Nasal swab polymerase chain reaction assay was positive for the severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus. Initial labs revealed acute kidney injury (creatinine, 1.86 mg/dl). Initial ferritin and IL-6 levels were within reference range. D-dimer was elevated at 306 ng/ml and C-reactive protein was elevated at 20.5 mg/liter. Treatment with hydroxychloroquine and nitazoxanide was initiated. Azithromycin was deferred because of a prolonged corrected QT of 517 ms. Immunosuppression with tacrolimus was resumed because of multiple episodes of allograft rejection in the past; however, mycophenolate and prednisone were stopped. Baseline urine studies had revealed mild nephrotic range proteinuria (1,973 mg/dl). Over the course of 7 days, his renal dysfunction rapidly progressed (creatinine peak, 7.78 mg/dl) with marked elevation in urine protein/creatinine ratio to 7,354 mg/dl. Inflammatory markers continued to rise (ferritin 637 ng/ml, IL-6 11 pg/ml, C-reactive protein 61.1 mg/liter, and D-dimer 1,562 ng/ml). Percutaneous needle core kidney biopsy showed acute tubular injury as well as collapsed capillary tufts with overlying visceral epithelial cell hyperplasia and protein droplets within Bowman's space, diagnostic of collapsing glomerulopathy (Figure 1 ). Electron microscopy revealed coronavirus particles within the tubular epithelial cells (Figure 2 ). There was no evidence of immune complex–mediated or monoclonal-associated disease. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti–double stranded DNA antibodies, HIV, and hepatitis serologies were negative. Chest radiography showed progressive patchy bilateral infiltrates consistent with atypical pneumonia; however, the patient remained afebrile with adequate oxygen saturation on room air and did not require respiratory support. His inflammatory markers subsequently downtrended, as his renal function improved with supportive care. He did not require dialysis and was eventually discharged home.

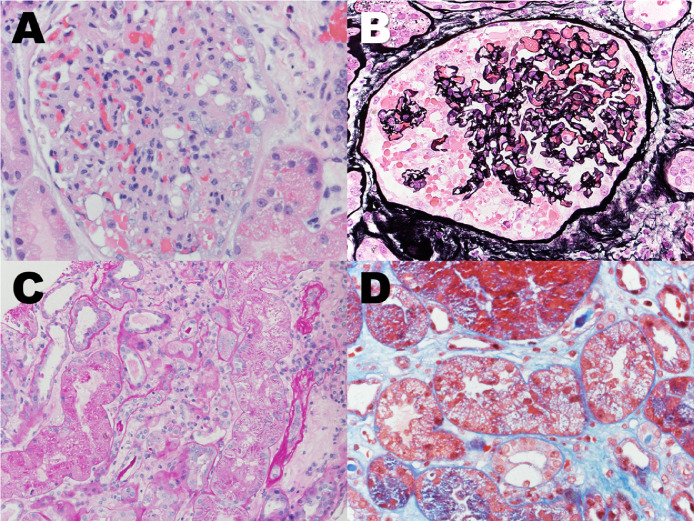

Figure 1.

Various pathological abnormalities of renal core biopsy from SARS-CoV-2 infection patient. (a, b) A glomerulus showed collapsed capillary tufts, overlying epithelial cell hyperplasia, and protein droplets within the Bowmen's space. (a) H&E stain, 400 × . (b) Jones Silver stain, 400 × . (c) Acute tubular injury. Proximal tubules showed sloughing off of the brush boarder, drop out of nuclear, and protein droplet within the cytoplasm. PAS stain, 400 × . (d) Isometric cytoplasmic vacuolization in the tubular epithelial cells. Trichrome stain, 400 × . H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; PAS, Periodic acid–Schiff; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus 2.

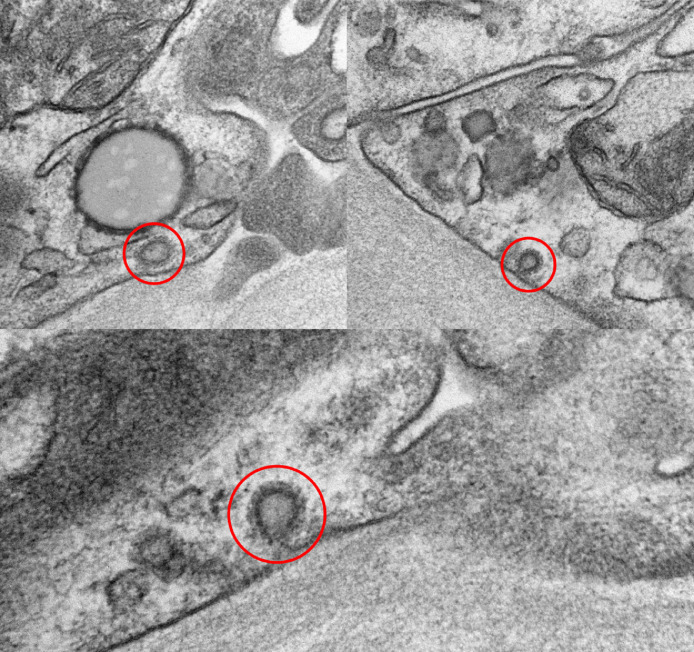

Figure 2.

Ultrastructure features of renal core biopsy from patient with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Coronavirus particles (red circle) in the cytoplasm of the tubular epithelial cells (transmission electron microscopy, 124,000 ×). SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus 2.

Collapsing glomerulopathy has a known association to viral infections, including the first SARS-CoV from the outbreak in 2002.1 To our knowledge, this is the first case of collapsing glomerulopathy associated with COVID-19 infection reported in a heart transplant recipient. Rare reports of similar cases in non-transplant patients have recently emerged in the literature.2 , 3 One case involved a 44-year-old African American female who was homozygous for the G1 risk allele in the APOL1 gene (a known risk factor for collapsing glomerulopathy).2 In that report, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in the biopsy specimen, but whether the patient's glomerulopathy was triggered by the virus directly or the resulting cytokine storm is unclear. Our patient had baseline proteinuria before transplantation and feasibly could have had an undiagnosed focal segmental glomerulosclerosis before SARS-CoV-2 infection; however, the rapidly progressive nature of his renal dysfunction and subsequent improvement following resolution of his illness suggests an association.

The incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) as a complication of COVID-19 has been variably reported. A case series of 116 patients from the initial outbreak in Wuhan, China did not show an association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and AKI.4 Conversely, AKI has been seen in 5% to 7% of hospitalized patients and up to 23% of intensive care unit cases in other studies.5 , 6 Moreover, baseline renal dysfunction and AKI were shown to be independent predictors of mortality in a prospective study of 701 patients.5 Fragments of SARS-CoV-2 RNA have been detected in urine sediment2 , 5; however, analysis of renal biopsy specimens were not performed in these reports. Kidney specimens from SARS-CoV in 2002 demonstrated moderate acute tubular injury without glomerular pathology or viral inclusion bodies.1 Notably, transplant patients were not included in these studies and little information is available to date on the natural history of COVID-19 and its interaction with baseline immunosuppressive regimens in this patient population.

References

- 1.Chu KH, Tsang WK, Tang CS. Acute renal impairment in coronavirus-associated severe acute respiratory syndrome. Kidney Int. 2005;67:698–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67130.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larsen CP, Bourne TD, Wilson JD, Saqqa O, Sharshir MA. Collapsing glomerulopathy in a patient with COVID-19. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:935–939. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kissling S, Rotman S, Gerber C. Collapsing glomerulopathy in a COVID-19 patient [e-pub ahead of print] Kidney Int. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.006. accessed April 16, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L, Li X, Chen H. Coronavirus disease 19 infection does not result in acute kidney injury: an analysis of 116 hospitalized patients from Wuhan, China. Am J Nephrol. 2020;51:343–348. doi: 10.1159/000507471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97:829–838. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]