Highlights

-

•

Reduced paid working hours of 40–59 year-olds is shaped by gender and carer roles.

-

•

Home ownership facilitates reducing paid work hours to perform unpaid care.

-

•

Consumption after reducing working hours is influenced by income and location.

-

•

A complex gendered relationship links environmental and social welfare concerns.

Keywords: Sustainable consumption, Care, Downshifting, Working hours, Consumers, Households

Abstract

The relationship between working hours and sustainability has attracted research attention since at least the early 2000s, yet the role of care giving in this context is not well understood. Focusing on Australians between 40 and 60 years who have reduced their working hours and income, we explore the relationship between working hours, care giving and consumption. Data from the national census (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2011, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016c) were analysed to contextualise patterns in paid working hours, income and carer roles for men and women aged between 40 and 60 years. Findings from a national survey on informal carers (ABS, 2016a) were also consulted. Taken together, the two sources of national data showed that two thirds of all informal carers are women, that the likelihood of assuming informal carer roles increases with age, and that men and women in carer roles work fewer paid hours per week and have a lower weekly income than non-carers of the same age. To gain qualitative insights into these patterns in Australian national data, and the likely implications of carer roles for household consumption, semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten households who subsequently recorded details of their consumption-related expenses over a seven-day period. The interview data showed the strong connection between carer roles, reduced income and paid working hours and its strongly gendered dimension. We argue that women primarily ‘downshift’ to undertake care rather than for sustainability motivations and that there is consequently a need to connect scholarship on gender and care with that on downshifting. The link between reducing paid working hours, care-giving and household consumption appeared to be less straight forward and varied between households. Our findings suggest that a complex relationship exists between environmental and social welfare concerns that has policy implications and warrants further exploration.

1. Introduction

The strong and widely recognised relationship between unchecked economic growth and environmental degradation (Jackson 2011) manifests at the household scale in the relationship between household income and levels of consumption, with increasing income leading to greater resource use (Ivanova et al., 2016, Wiedenhofer et al., 2018). To date, the only check on the global trend of increasing household consumption and its associated environmental impacts has occurred during global economic downturns and this is quickly reversed when economic conditions improve (Peters et al. 2011). The unfolding economic consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic, while historic in scale, may well follow a similar trajectory. While ideas of prosperity without growth (Jackson 2011) and de-growth (Kallis 2017) have been a consistent focus in academic research for some decades, government policy in affluent countries such as Australia remains strongly focused on exponential economic growth – and this focus is likely to be vigorously renewed as the pandemic subsides in major economies. Household expenditure, reported through the system of national accounts, is considered an important measure of the health of the domestic economy and Australia has one of the highest rates of per capita household consumption in the world, with food, energy and transport the most environmentally consequential consumption domains (Ivanova et al. 2016). Yet this disguises the fact that Australian households do not uniformly increase their income over time, while some households actively decrease it. In this paper we focus on this latter phenomenon through examining the characteristics of those of working age (40–59 years) who reduce their paid working hours and income and thus potentially constrain household expenditure. In doing so, we are particularly interested in understanding the relationship between levels of household consumption and the complex interweaving of paid working hours, gender, and carer roles within households.

We draw, here, on two distinct bodies of scholarship that have developed independently of one another. The relationship between gender, care and consumption has been a central theme in feminist social research which has long argued that unpaid domestic labour be included in definitions of work and studies of working life. A strand of this scholarship has focused on social concerns around work-life balance in the context of long hours spent in paid work and commutes (Pocock, 2005, Bittman and Ironmonger, 2011, Rau and Edmondson, 2013). A somewhat different body of scholarship has developed around the problem of escalating consumption within highly urbanised societies that focuses on the relationship between hours spent in paid work and increasing levels of consumption (Hamilton and Mail, 2003, Schor, 2005, Pullinger, 2014). In recognising this nexus between labour and consumption, Jackson (2005) argued that reducing consumption could deliver a double dividend - allowing improved quality of life as well as reducing environmental impacts - although he cautioned that the social and cultural changes involved would require “sophisticated policy interventions at many different levels” (Jackson 2005: 32). In this context, the phenomena of downshifting has, since the early 2000s, attracted the attention of a number of researchers seeking to understand the potential for voluntary reduction in consumption. Generally defined as a voluntary reduction in paid working hours and income in order to live better quality lives with lower levels of consumption (Chhetri et al., 2009, Kennedy et al. 2013), downshifting is hypothesised to connect issues of ecological sustainability, social justice and individual wellbeing (Schor, 1998, Schor, 2001). Various studies have suggested that voluntary reduction in paid working hours is linked with increased investment of time in both care-giving and leisure activities, while the consequence for household consumption appears to be more ambiguous (Nässén and Larsson, 2015, Buhl and Acosta, 2016, Hanbury et al., 2019). A key issue, then, is whether resource intensive forms of consumption are replaced through downshifting by time intensive forms with lower environmental impacts (Kallis et al., 2013, Nässén and Larsson, 2015, Buhl and Acosta, 2016, Wiedenhofer et al., 2018).

Our Australian-based study of people who have voluntarily reduced paid working hours specifically focused on the significance of carer roles in influencing both decisions to reduce working hours and the subsequent patterns of household consumption. Care-giving has received little attention in previous research investigating working hours, consumption and sustainability implications, yet the importance of linking wellbeing and social and gender equity concerns with environmental concerns has been strongly emphasised by advocates of degrowth, who caution that any policy move to reduce working hours and income without attending to these social dimensions is fraught with peril (Kallis et al., 2013, D’Alisa and Cattaneo, 2013). Political scientists have similarly argued the need for strategic policy connections to be made between the welfare state and the green state (Kronsell and Stensöta 2015).

1.1. Research on downshifting and consumption

Research on downshifting has explicitly examined the links between reducing working hours and consumption. Downshifting has mainly been studied in affluent countries with a predominant focus on quality of life outcomes; and early research linked downshifting with lifestyle residential transitions such as tree changing or sea changing by people who are in a position to make such choices (Etzioni and Taylor-Gooby, 1998, Hamilton and Mail, 2003). However, such niche phenomena may not reflect the character of reducing paid work across the wider population. When defined simply as a decision to reduce paid working hours and income, regardless of political viewpoint, downshifting is likely to capture a wider range of motives (Chhetri et al 2009).

Studies using this broader definition of downshifting have been undertaken in several countries, with some drawing on survey data with large samples. Chhetri et al. (2009) surveyed an adult population (aged 18 years and older) in SE Queensland, Australia, in the late 1990s when the region was experiencing rapid population growth due to lifestyle in-migration, in order to identify the demographic profile and motivations of downshifters in that region. Based on a definition that included households of all ages in which at least one adult had voluntarily reduced income and working hours, they identified three clusters of downshifters with shared demographic characteristics:

-

1)

family-focused change-seeking mature downshifters, characterised by married couples with children and high levels of education and income,

-

2)

non-working, mature married women downshifters (who were generally less educated and older than cluster 1); and married couples on low incomes drawn from paid work, superannuation, and/or welfare payments,

and

-

3)

singles and single parent 'ecocentric' disadvantaged downshifters, who were overwhelmingly people living in non-conventional households or either alone or in shared households (often apartments).

The third cluster included a high number of single mother households as well as people undertaking part- or full-time study. The authors found that the main motives for downshifting across their whole sample were to gain more control and personal fulfilment in life, to spend more time with family, and to lead a healthier and more balanced life. Downshifters in the Chhetri et al. study were more likely to be women in households in a middle-income bracket and their reduction in income did not significantly constrain household consumption.

A similar approach was adopted by Kennedy et al. (2013) who surveyed downshifters in Edmonton in Alberta, a Canadian province characterised by higher than average working hours and household income. Downshifting was found to be strongly related to household structure, with downshifter households more likely than non-downshifters to have children. Spending more time with children was a main motivator for 42% of these downshifter households, followed by valuing leisure time over additional income (20%). Environmental concerns and reducing consumption did not feature at all in survey responses; evidence that counters the conclusions of earlier work that aligned downshifting with environmental social movements (Schor, 1998, Hamilton and Mail, 2003). Further, Kennedy et al. (2013) specifically focused on exploring quality of life and pro-environmental behaviours, including sustainable consumption practices. Once again, however, survey respondents did not report significant improvement in their quality of life, nor did they report using more sustainable forms of transport. Nevertheless, respondents did report a shift towards more sustainable household practices; a result, if not an intention, of their downshifting experience that can be interpreted as a form of inadvertent environmentalism (Hitchings et al. 2015).

Other studies have been framed around the relationship between time use and resource consumption. A qualitative study conducted with seventeen relatively affluent Swiss employees who had voluntarily reduced their paid working hours found that their newly gained time was primarily allocated to parenting or further education activities and, to a lesser extent, voluntary work (Hanbury et al. 2019). These activities were attributed to preference rather than financial necessity but, as a consequence, there was no increase in discretionary time for leisure activities. Some carbon-intensive activities such as travelling or shopping were reduced due to financial constraints. In an earlier study, drawing on data from a Swedish Household Budget Survey and the Swedish Time Use Survey, Nässén and Larsson (2015) assessed the implications of shorter working hours for greenhouse gas emissions from Swedish households. They found that a decrease in paid working hours could have a significant impact in reducing both energy use and greenhouse gas emissions which was largely explained by the strong relationship between paid working hours, income and consumption. However, a more complex picture emerges from a study of the rebound effects resulting from the freeing up of time through reduced paid working hours of downshifters in Germany (Buhl and Acosta 2016). Drawing on interviews and data from national time use surveys, this study examined how time and expenditure budgets were rearranged through downshifting and assessed the implications of this for resource use in households. In doing so, Buhl and Acosta found that downshifters allocated their newfound time to hobby pursuits, childcare and, to a lesser extent, housework, educational activities and sleep. The prioritising of these activities was strongly influenced by family status and gender, with women spending more time on household chores, errands and childcare, and men on leisure, repairs and hobbies, findings that corroborate those of an earlier study in the UK (Druckman et al. 2012). While allocating time to these activities increased levels of social engagement and sense of wellbeing, Buhl and Acosta found that the benefits for reduced household consumption were less clear, as some leisure activities involved more intensive resource use. While the net effect on resource use was found to be beneficial, the authors concluded that other policy measures, such as increased taxes on resource intensive goods and services, were needed to steer the use of leisure time towards more environmentally desirable activities.

1.2. Research on gender, care and consumption

The altruistic motives of household consumption as an expression of care-giving within households and families has been well documented (Miller, 1998, Gronow and Warde, 2001, Lindsay and Maher, 2013). Recent social research focused on household consumption, particularly energy, has examined change over the life course, finding it linked with the assumption of new carer roles, change in household income, and change of dwelling (Groves et al., 2016, Shirani et al., 2017, Burningham, 2017). A recent study of time use across the American population found that older individuals were more likely to have days that are dominated by household activities and carer roles, engagement in leisure, and early and short day paid work (Flood et al. 2018).

Much of the scholarship on care, particularly geographies of care, draws on the definition of care provided by feminist theorists Fisher and Tronto as,

“… activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, continue, and repair our 'world' so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, our selves, and our environment, all of which we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web.” (Fisher and Tronto 1991)

Tronto (1993) argued that care be recognised as a central concern of human life and articulated an agenda for embedding an ethic of care in political and social institutions. Geographies of care research has strongly focused on the consequences of the withdrawal of state sponsored care, particularly for disabled and elderly under conditions of neoliberalism and state austerity, for carer roles in households and families and for the home as the primary site for care provision (Cox, 2013, Higgs and Gilleard, 2016, Power and Hall, 2018, Williams, 2020).

Recent conceptualisation of the material dimensions of care, encapsulated by Puig de la Bellacasa (2017) in the phrase, ‘matters of care’, may be useful for linking the social and environmental motives and consequences of household consumption practices. In keeping with Fisher and Tronto’s (1991) definition, Puig de la Bellacasa (2017) extends traditional notions of care for other persons, as in parental care or health care, to include aspects of the material environment, bringing a new emphasis on the role of materials in facilitating relations among humans and reframing care as a socio-material relation (Power 2019). These insights support our research focus on the potential connections between care-giving and the material aspects of consumption.

While studies of downshifters, particularly those that have included young adults, have identified a pattern of women reducing working hours to look after children (Stone 2010), we argue that carer roles (i.e. unpaid care work) have not been adequately unpacked in the downshifting literature, with the motivation of “spending more time with the family” (Hamilton and Mail, 2003, Chhetri et al., 2009, Kennedy et al., 2013) potentially incorporating a wide range of carer roles and activities. We acknowledge that caring involves affective and relational dimensions but critically, care also involves unpaid domestic labour. The gendered nature of paid and unpaid labour markets means that women are more likely than men to reduce or limit their paid labour to undertake caring labour (Maher et al., 2008, Lilly et al., 2010). The findings of Buhl and Acosta (2016) on the different ways in which male and female downshifters allocated their time signal that the everyday experience of downshifting may also be strongly gendered. Our research explicitly addresses the relationship between care-giving, working hours and consumption through a focus on two key questions: 1) What is the relationship between carer roles, reduced paid working hours and income, and 2) How does care-giving among people who have reduced their paid working hours affect household consumption? The influence of gender and changes over the life course underpin both questions.

2. Research design and methods

Our study drew on and analysed two existing national data sets, the national census for 2006, 2011, and 2016 and the summary findings of a 2015 national survey of informal carers in the Australian population. We also conducted qualitative research interviews with ten householders who had, ostensibly at least, voluntarily reduced their working hours. The relationship between care-giving, working hours and income (research question 1) is examined through analysis of national survey data. The relationship between reduced working hours, care-giving and consumption (research question 2) is examined through the analysis of householder interviews and self-recorded consumption diaries.

2.1. Quantitative analysis of national census data and a national survey on informal carers

Our analysis of national census data specifically focused on the relationship between working hours and carer roles among 40–59-year-olds in the Australian census. This age cohort comprises people of working age who are less likely to be caring for young children than those under 40 years. In 2006 18.6% of the population were in this age cohort, in 2011 19.6%, and in 2016 18.7% (ABS, 2016b). Australia’s national census includes questions about hours worked, income and informal (unpaid) carer duties. It is conducted every five years and all Australian households are required to return responses. Our analysis first sought to identify patterns in hours worked of men and women between the ages of 40 and 60 years over the 2006, 2011 and 2016 census years. As previous studies have tended to report changes in working hours and carer roles over the whole life course, the 10-year span of these three census collections provided an opportunity to track how working hours changed for Australians aged 40 and over as they aged. The data was extracted through the Tablebuilder database provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS, 2016b). However, data provided through this facility is structured in a way that only enabled us to conduct bivariate or trivariate analyses. As individual level data is not provided, it is not feasible to test causal relationships using regression techniques. Nevertheless, the advantage with census data is that all analyses are based on a full count of the population (e.g. in 2016 there were 2.1 million women and 2.3 million men who were aged 40–59 years and employed), thus making tests for statistical significance redundant.

Next, to understand the socio-demographic profile of informal (i.e. unpaid) carers in the Australian population, we drew on summary findings from a separate 2015 national survey on Disability, Ageing and Carers in Australia (ABS, 2016a). This survey provided a more detailed socio-demographic profile of informal care providers and categories of care across the population in 2015 drawing on respondents from over 25,500 private dwellings. Finally, we returned to the national census data to examine the relationship between carer roles and income. Together, these two national data sets provided clear evidence of a relationship between working hours, income, and carer roles and how these change for women and men between the ages of 40 and 60 as they age. This furnished an understanding of the broader context in which our qualitative research with the ten downshifting households could be situated.

2.2. Semi-structured interviews with participants from households who had voluntarily reduced their paid working hours

The ten households participating in this study were identified by a market research firm engaged to recruit people of working age (between 40 and 60 years) who had voluntarily reduced their paid working hours and income in the last five years. By selecting households in this way, we sought to avoid the phenomena of involuntary redundancy. However, the voluntary character of reducing working hours among the ten study recruits was unclear for some participants and this issue is discussed further in the analysis below. Five participants were from Melbourne and five from the Bendigo region in central Victoria, and nine of the ten were women. Participants varied in household income, home ownership status, and in their household type. Eight lived in couple households, while two were single and six of the participants had children, teenagers or young adults living at home. Table 1 provides summary details, including employment profile, location, household type, and home ownership status.

Table 1.

Summary of the 10 Downshifter research participants.

| Name | age | Location | Household type | Housing status | Previous Job | Current Job | Year down-shifted | Current household Income bracket | previous working hours/wk | current working hours/wk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katya | 47 | Docklands, Melbourne | Couple expecting baby twins | Owner (mortgage) | Parole officer | Parole Officer | 2015 | Medium | 40 | casual |

| Lisa (& Paul) | 42 | Laverton, Melbourne | Couple only, husband retired | Own outright | Medical secretary | Medical Secretary (self-employed) | 2016 | Medium | 50 | 24 |

| Kimberly | 47 | North Bendigo | Couple with preschool aged child | rents | Drug & Alcohol Counsellor | Casual shifts for disability support | 2016 | low | 30 | 20 |

| Christi | 48 | Brighton East, Melbourne | Couple with son in early high school | Owner (large mortgage) | Manager in Vic Govt Ed Department | Manager in Vic Govt Ed Department | 2015 | Medium-high | 50 | 24 |

| Angela | 60 | Hampton, Melbourne | Single mother with adult son living with her | rents | Public servant, Dept of Education | Integration Aid | 2014 | low | Changed from FT to PT and now retired | 0 |

| Sharon | 56 | Bendigo | Shared with home stay student | Owner (small mortgage) | University work, local council | Previously academic and policy work | 2009 | low | 0 | |

| Sandra | 57 | Bacchus March, near Bendigo | Couple with teenage child | Owner | Small business owner (café) | Aged Care | 2012 | low | 50 | 24 |

| Mick | 40–45 | Eaglehawk, Bendigo | Couple with adult child | renting | Disability support worker | Disability support worker | Mid 2016 | low | 38 | 22 |

| Maria | 45 | Kangaroo Flat, Bendigo | Couple | renting | Mining accountant | student | 2011 | Medium | Studying full time | |

| Jenny | 52 | Bendigo | Couple, one adult child at home | Owns house – one address 22 years | Self employed merchandise and retail | Student of community services | Apr 2017 | Medium (husband fully employed) | 50 | 5 (+study hrs) |

Interview questions were aimed at eliciting participants’ motives for reducing paid working hours and their subsequent experiences. Specific questions asked about changes experienced since changing their working patterns in three key consumption domains: food preparation, transport and leisure. These three consumption domains were targeted due to their significant environmental impacts (Ivanova et al. 2016). Each interview concluded by asking participants to reflect on how they felt about reducing their paid working hours in terms of their sense of being in control, their experience of self and wellbeing, and their social interactions. Interviews were recorded and fully transcribed. Following the interview, each participant was asked to record details of their daily consumption activities and daily expenditure in relation to food, transport and leisure for seven consecutive days. Records of expenditure provided an indicator of consumption patterns and a means of comparing the consumption activities of study participants. The consumption diaries also prompted each participant to reflect on how their consumption and spending patterns had changed since downshifting.

Analysis of the qualitative data took the form of a careful reading of the transcripts to systematically identify participants’ motives and experiences of work reduction. Notes on motives and experiences were then collated to reveal common themes and points of differences among the study participants. Any comments made in interviews about how downshifting had influenced consumption were also linked with the diary records. The analysis provided here specifically focuses on insights around the experience of reduced paid working hours, reduced income and carer roles that help to explain the patterns that emerged from the analysis of national survey data, and that provide some indication of how these experiences may affect consumption practices. A more detailed analysis of the affective experience of these ‘downshifters’ is provided in a separate publication (Lindsay et al., 2020).

3. Analysis of national census data

3.1. Paid workforce participation patterns over the life-course differ for women and men

As indicated above, we followed a single age cohort of women and men across three census years (2006, 2011 and 2016) to establish how average paid working hours per week changed as they aged. Sample sizes for the cohorts are shown in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Number of people by age and gender in the 2006, 2011 and 2016 Australian censuses.

| Age | Gender | 2006 | 2011 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40–44 | Male | 573,538 | 605,040 | 612,010 |

| Female | 512,469 | 549,970 | 562,518 | |

| 45–49 | Male | 561,950 | 587,682 | 598,157 |

| Female | 522,173 | 551,937 | 573,682 | |

| 50–54 | Male | 498,022 | 552,384 | 562,242 |

| Female | 446,258 | 516,561 | 532,507 | |

| 55–59 | Male | 415,139 | 453,758 | 492,191 |

| Female | 325,131 | 394,330 | 452,877 | |

| 40–59 | Male | 2,048,651 | 2,198,860 | 2,264,600 |

| Female | 1,806,039 | 2,012,802 | 2,121,584 |

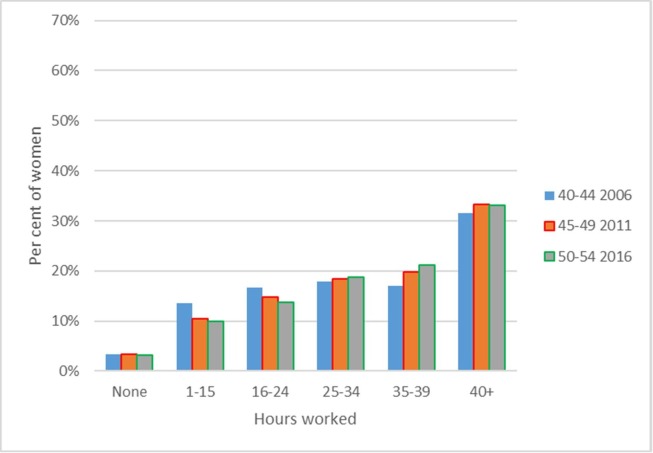

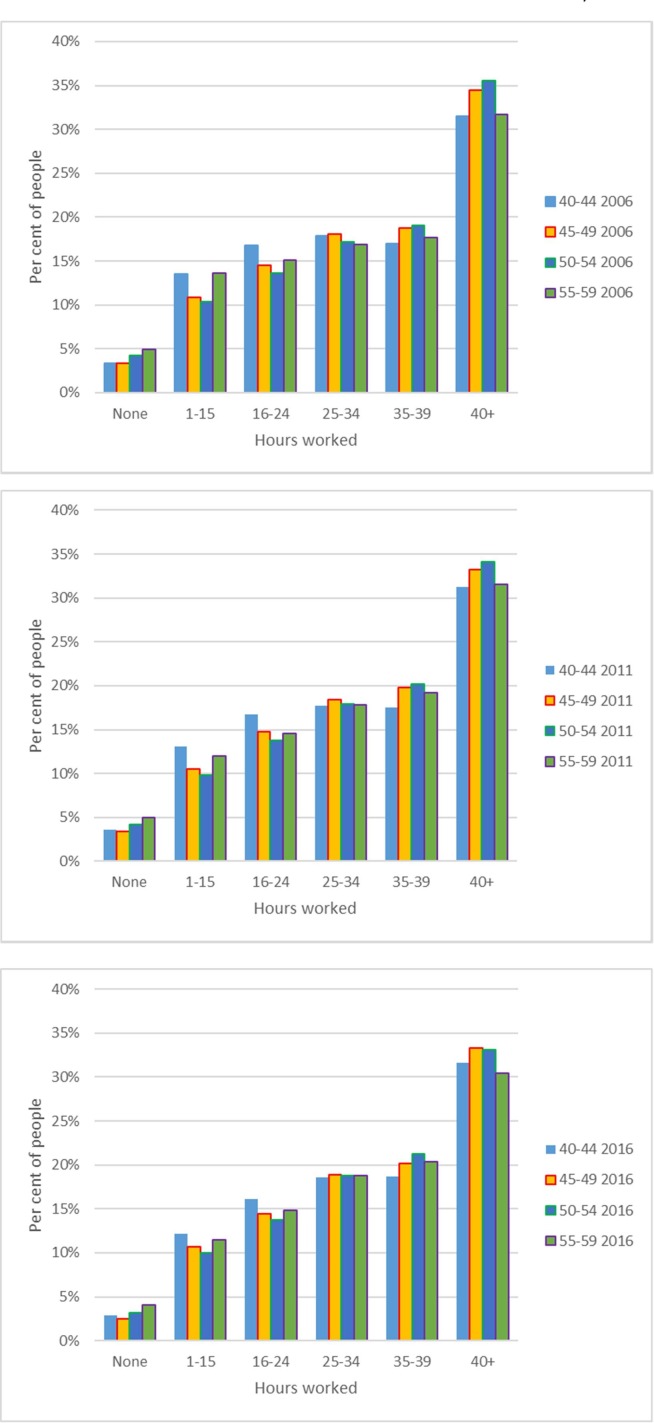

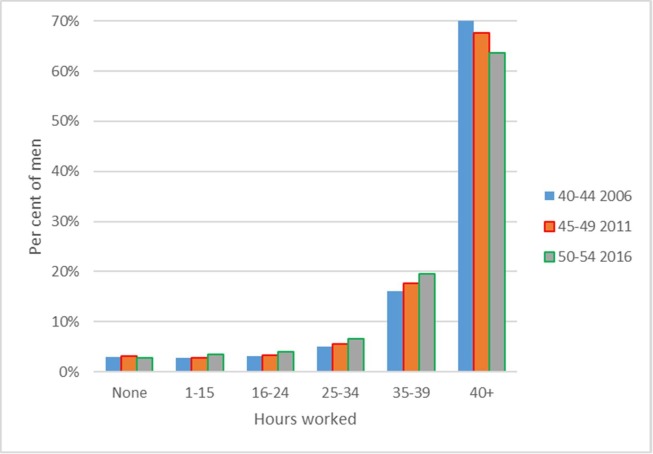

Fig. 1 shows the pattern of paid hours worked by the cohort of women who were aged 40–44 in 2006, following them over the three census periods. These women increased their paid working hours noticeably after entering their mid-40s and tapered off slightly as they entered their mid-50s. Fig. 3 shows a distinctly different pattern for the paid hours worked by the cohort of men who were aged 40–44 in 2006. While paid working hours for women fluctuated over the ten-year period, paid working hours for men in the same age cohort remained relatively stable.

Fig. 1.

Hours worked per week for women aged 40–44 in 2006 and the same cohort in 2011 (aged 45–49) and in 2016 (aged 50–54).

Fig. 3.

Hours worked per week for four age cohorts of women in 2006, 2011 and 2016.

Fig. 1. Paid hours worked per week for women who were aged 40–44 in 2006 (shown in blue), and the same cohort aged 45–49 in 2011 (shown in red) and aged 50–54 in 2016 (shown in green).

Fig. 2 . Paid hours worked per week for men who were aged 40–44 in 2006 (shown in blue), the same cohort aged 45–49 in 2011 (shown in red) and aged 50–54 in 2016 (shown in green).

Fig. 2.

Hours worked per week for men aged 40–44 in 2006 and the same cohort in 2011 (aged 45–49) and in 2016 (aged 50–54).

The most likely explanation for the contrasting patterns for women and men is that many women are caring for children in their early 40s and return to longer paid workforce hours as their children become more independent. In order to establish if the pattern shown in Fig. 1 applied to older age cohorts less likely to be caring for children, we charted the paid working hours for women in four different age cohorts in 2006: 40–44, 45–49, 50–54 and 55–59, then compared that with the same age cohorts in 2011 and 2016 (Fig. 3). In each successive census year, the paid hours worked by women aged 40–59 years increased over the 10-year time span and, by 2016, there was less difference between the paid working hours of women in the four age groups (depicted in Fig. 3). This pattern of change seems to align broadly with a national trend of increasing paid working hours over time. An analysis of labour force survey data for the period 1978–2010 showed that the average actual weekly hours worked for full-time and part-time employed people, for both men and women of all ages, have increased steadily (HILDA 2016).

Fig. 3: Paid hours worked per week for four age cohorts of women in 2006, 2011 and 2016.

The slight differences in the shape of the four curves representing four different age cohorts at three points in time (2006, 2011 and 2016) show that women work less paid hours in their early 40s (probably due to parental roles), increase their paid working hours through their late 40s and early 50s, then reduce them again in their late 50s. These findings correspond with those of international studies on time use and gender differences in parenting (Craig and Mullan 2010) and on the relationship between carer roles and paid working hours more generally (Bauer and Sousa-Poza 2015).

The difference between paid working hours of women and men in their 40s (shown by the very different shaped curves in Fig. 1, Fig. 2) is not particularly surprising and likely reflects the prevalence of women in part time and less secure employment (Craig and Mullan 2010) as well as their movement in and out of the paid workforce linked to raising children. However, there may be other dynamics at play as men and women age, with women assuming a wider range of carer roles, including for elderly relatives and adult children with special needs (Bauer and Sousa-Poza 2015) – and examples of these are discussed in our analysis of the interview research below.

3.2. Gender and age are significant for informal care provision in Australia

To understand the demographic profile of carers across the Australian population, we reviewed summary findings from the national survey on Disability, Ageing and Carers, conducted in 2015 (ABS, 2016a). The Australian Bureau of Statistics defines a carer as, ‘a person who provides any informal assistance, in terms of help or supervision, to people with disability or older people (aged 65 years and over). Assistance must be ongoing, or likely to be ongoing, for at least six months’, and a primary carer is, ‘a person who provides the most informal assistance, in terms of help or supervision, to a person with one or more disabilities, with one or more of the core activities of mobility, self-care or communication’ (ABS, 2016a). Table 3 lists the categories of care giving practices recognised by the ABS.

Table 3.

Categories of care giving practice used by the ABS.

| Broad area of activity where assistance is required or difficulty is experienced: |

| 00. Not applicable |

| 01. Mobility (excludes walking 200 m, stairs and picking up objects) |

| 02. Self-care |

| 03. Oral communication |

| 04. Health care |

| 05. Cognitive or emotional tasks |

| 06. Household chores |

| 07. Property maintenance |

| 08. Meal preparation |

| 09. Reading or writing |

| 10. Private transport |

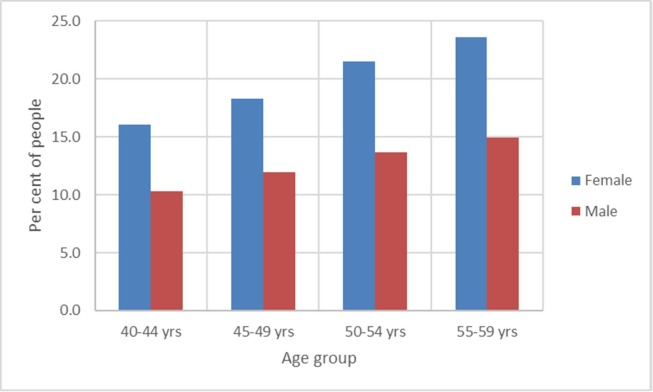

The average age of informal carers in Australia in 2015 was 55 years and two thirds of all informal carers were female. While women in the 40–59 age group were more likely to be primary carers than men, both men and women were equally more likely to become primary carers as they aged (ABS, 2016a). Using national census data, we generated a more detailed picture of informal carers across the 40–59 age group that indicates how the likelihood of carer roles increases with each five-year age increment.

Fig. 4 . Percentage of informal carers in Australia aged 40–59 by gender and age in 2016 (ABS, 2016a).

Fig. 4.

Percentage of informal carers in Australia aged 40–59 by gender and age in 2016 (ABS, 2016a).

A further pattern identified from the 2015 survey was that carers, both women and men, were more likely to own the home they live in and have no debt, as opposed to paying off a mortgage or renting accommodation (ABS, 2016a). Rates of home ownership in Australia have decreased over time and the decline between 2001 and 2014 was mainly experienced by those in younger age cohorts (HILDA 2016: 68). This means that while the likelihood of carer responsibilities increases with age (along with an associated decrease in weekly income), the likelihood of owning a home outright is also higher. It may be the case that the financial security provided by home ownership makes it more feasible for carers to survive on a lower income. Our interview research, discussed below, provides insights into how home ownership influenced participants’ capacity to reduce their paid working hours.

3.3. A strong negative relationship exists between labour market participation and carer roles.

We conducted further analysis of census data to identify patterns in paid working hours of individuals in carer roles for the four age cohorts spanning 40 to 59 years of age. Across all age cohorts, women and men who provided care were less likely to be employed and those who were employed were less likely to be in full time employment. Carers in their 40s, regardless of gender, were more likely to have completely withdrawn from the labour market than work part time. Compared with those in their 40s, carers in their 50s were more likely to work part time; 1.5 percentage points more likely for the 50–54 age group and 2 percentage points more likely for carers aged 55–59, regardless of gender. This could be due to increased care burdens due to looking after older partners, ageing parents and/or grandchildren or managing their own health issues.

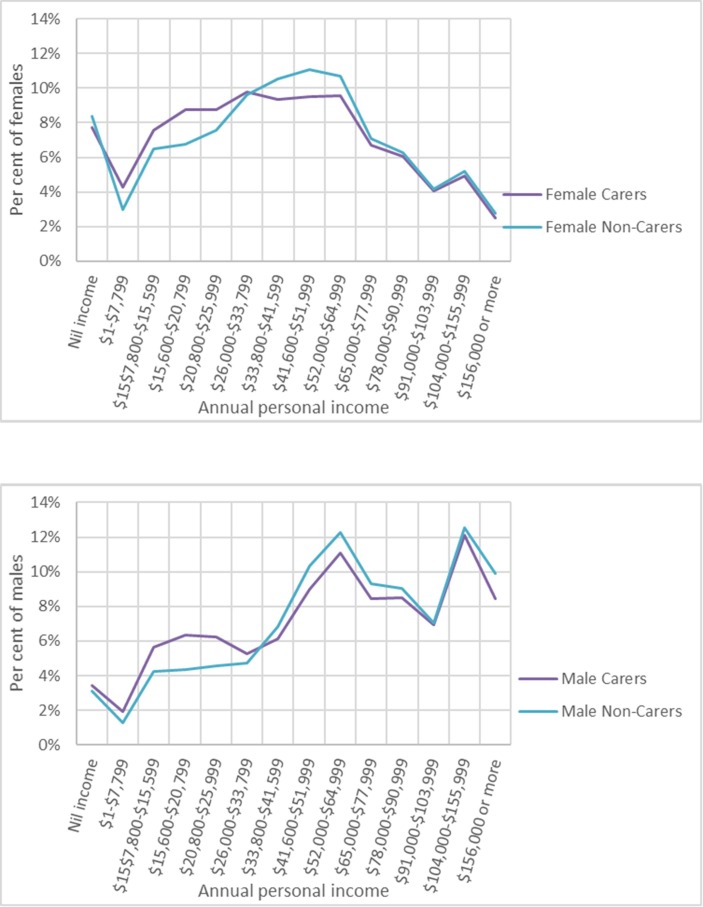

As part time work is likely to affect personal income, we examined national census data from 2016 to explore the relationship between paid working hours and income. For women, those in the 45–49 age group had the highest income, compared with those aged 40–44 and those aged over 50, perhaps reflecting the broader pattern of paid working hours for women shown in Fig. 3. The pattern differs for men whose income is higher for successive age groups. Fig. 5 contrasts the income of carers and non-carers in the 50–54 age group for men and women. It clearly shows that the annual personal income of both women and men providing unpaid care is less than those who do not provide care. The proportion of people earning $33,800/yr or more was greater for those who provided no unpaid care (e.g. 59% of women aged 50–54 years) compared to those who provided care (e.g. 50% of women aged 50–54 years) i.e. care-provision is associated with lower income. These proportions did not differ significantly across the 40–59-year age classes.

Fig. 5.

Annual personal income for carers and non-carers by gender, for those aged 50–54 in 2016.

Fig. 5. Annual personal income for male and female carers versus non-carers aged 50–54 in 2016, based on 2016 census data.

In summary, while the analysis of census data can only trace age cohorts over time and not individuals, our analysis reveals a significant difference in the patterns of men’s and women’s paid working hours as they age, with men’s paid working hours remaining constant and women’s paid working hours peaking in their late 40s and reducing in their late 50s. Informal carers across the Australian population are predominantly women, and the likelihood of carer roles increasing with age helps to explain these differences. Based on the analysis of census data and the summary findings from the national disability survey presented above, we draw the following conclusions around the relationship between paid working hours, care-giving and income:

-

(i)

There is a strong negative relationship between paid working hours and informal care-giving for both men and women between 40 and 59 years of age.

-

(ii)

Women are significantly more likely to have lower paid working hours than men, particularly those in the 40–44 age cohort and the 55–59 age cohort.

-

(iii)

Women and men who provide informal (unpaid) care are likely to earn less than those who do not provide care.

-

(iv)

The different pattern of personal income for women and men aged 50–54 may reflect the much larger portion of women performing unpaid carer roles.

-

(v)

Informal carers, both women and men, are likely to be home owners.

-

(vi)

Informal carers in their 40s, both women and men, are more likely to withdraw completely from the labour market compared with those in their 50s who are more likely to work part time.

From these conclusions we can infer that carer roles are likely to impact on household consumption based on the known relationship between income and resource consumption at the household level. The link between high household income and high levels of consumption is well established (Ivanova et al. 2016) but the impact of care on this dynamic is yet to be clarified. On the one hand, we note that carer roles are linked to low personal income, as primary carers of working age are likely to work fewer paid hours than non-carers. On the other hand, carers are more likely to be home-owners which suggests that some measure of financial security is necessary to support the take up of informal care work over paid work. Our interview research provides further insights into how these dynamics of gender, care, paid working hours and home ownership play out within the downshifting household.

4. Key insights from interviews and consumption diaries

4.1. Significance of care-giving in the decision to reduce paid working hours

Among participants in this study, motivations for reducing paid working hours included changing family circumstances, carer responsibilities, work-related stress, declining work opportunities and personal health. It was not always possible to determine whether reducing paid employment was entirely voluntary or partly a response to a change in work opportunities or conditions, health concerns of participants, or a need to provide care to family members. However, a key finding was the prevalence of carer roles following a reduction in paid working hours, with nine of the ten participants performing informal care labour for family members. For some, this was given as the main reason for reducing paid working hours. Even when care-giving was not given as a reason for reducing paid working hours, it was evident that more time was subsequently invested in caring labour. In this respect, care-giving appeared to problematise the notion that reducing paid working hours and income is a voluntary decision. In our sample, dominated by women, gender and care-giving appear to be central to understanding the reduction in paid working hours.

Care-giving activities included participants visiting aging parents who lived in a different location and assisting with various household tasks, but also often involved caring for live-in older children, in some cases children with special needs (Table 1). For example, Sandra (aged 57) decided to reduce her paid working hours following a divorce and her remarriage to retiree Peter (aged 69). Her 18-year-old son, who and lived with them while undertaking a trade apprenticeship, had health problems and was dependent on her support. Sandra previously worked full time running a cafe but at the time of interview worked part time in an aged care facility. Since downshifting, she has invested considerable time caring for her aging parents who live 100 km away and also assists her sister and elderly aunt with their needs. Lisa (aged 42) provides a further example of reducing paid work to prioritise care. She reduced her working hours as a medical practice manager in order to support her partner Paul (aged 61) following the death of his adult son in a car accident. Besides downshifting allowing time for grieving and partner support, she wanted to reduce work stress and prioritise leisure travel with Paul, who had fully retired. Care of the self was also a motivation for reducing paid working hours. For example, Christi (aged 48) reduced her long working hours as a manager in a government agency to manage work-related stress and allow time to care for herself. She now spends more time socialising with friends and family members which she finds personally fulfilling (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Summary of self-recorded consumption diaries showing expenditure and reflections for three consumption domains over a seven-day period. *Missing diary data for Kimberly.

| Food ($) | Comments on food | Transport ($) | Comments on transport | Leisure ($) | Comments on leisure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katya | 340 | Walked to local Docklands grocery store. | 40 | transport expenses are mainly petrol for car | 330 | Included dining out with friends and family and shopping as a leisure activity, and watching TV. |

| Lisa | 180 | Shops for groceries at Aldi. | 41 | Short car trips often involving relatives. | 80 | Watches TV and Netflix and crochets. Jewellery shopping. Walk around the block. |

| Kimberly* | ||||||

| Christi | 345 | 2 supermarket grocery shops and eating out with friends & family. Spends more time preparing meals at home now. | 34 | Takes train to city on work days and uses car on other days (for shopping and social engagements) | 155 | Walking the dog, cooking, reading and watching TV. Is more social since downshifting and has time at home for activities other than chores. |

| Angela | 253 | Shops at supermarket for convenience and makes frequent small purchases. | 68 | Multiple short car trips for shopping. | 22 | Gardening, playing computer games and watching TV at home. Drove to the beach one day. |

| Sharon | 160 | Frugal with grocery shopping and largest expenses are linked to social events. | 35 | Short car trips and longer drive to visit boyfriend in a different town. | 11 | Doesn’t go out much for both health and financial reasons. Social events, visit to local gallery and op shop are main leisure activities. |

| Sandra | 68 | Shops at supermarket for value for money, take-away pizza one night. Dined one night with parents (mother cooked) | 105 | Drives to shops, drives both her son and herself to work (son has L plates). Drives son to gym. Long car trip to visit parents on other side of Melbourne. | 100 | Home – TV,Out – Bingo, movies, walked dog |

| Mick | 73 | Few details but mainly eats at home | 70 | Short car trips, mainly for trips to the gym and work place. | 0 | Gym workouts, walking, house and garden jobs, watching TV. |

| Maria | 35 | Shops at supermarket for convenience and value and dines at home – didn’t eat out at all. | 18 | Multiple short car trips to shops and athletics track. | 25 | Home - reading, online entertainment, letter-writing, stamp collecting, TV. Away from home – athletics training, visiting library. Didn’t compete in athletics comp. due to cost but trained with the other team members and socialised. |

| Jenny | 96 | Single weekly grocery shop at Chinese market. | 10 | Short car trips. | 26 | Goes out less due to lack of money. Feels isolated but loves staying at home. Leisure activities are gardening and watching movies on iPad. Only spent money on monthly meal at the pub with daughter |

Like Christi, a number of participants reported that they experienced less stress and felt more in control of their daily lives on account of having more time for planning activities. Some participants, for example, explained that since reducing paid working hours they were able to invest time researching value for money holidays or cheaper energy, mobile phone or data plans. However, the experience of gaining greater control of leisure and expenditure choices was not shared by all. Indeed, those who retained a relatively high-income level were much more likely to feel they had gained control through downshifting – even when they were providing informal care to others – while those with low income were more likely to discuss the impact of reduced income – and caring activities – in limiting choices around consumption, including the type of food they purchased, options for leisure activities and, in one case, transport options. For participants in this study, key influences on disposable income were their earning capacity for those hours they still worked, their partner’s income, and whether or not they owned their own home or made regular mortgage payments or paid rent as we discuss below. At least one participant was actively seeking full time employment and three others anticipated increasing their paid working hours in the future.

4.2. Housing, consumption, and care

The geographic location of dwellings had a substantial impact on experiences after reducing paid work, and affordable housing and home ownership appeared to be particularly important for many participants, with ownership/affordability enabling both a reduction in income and the provision of greater levels of informal care for others or for self-care. Not only did home ownership enable participants to reduce their paid working hours, it influenced their subsequent feelings of having control over their lives, a finding that endorses similar observations made by Stone (2010) and corroborates the national data on carers in the Australian population detailed above. As Bowlby (2019) has noted, the home is a critical resource for the provision of care.

In some cases, the opportunity to downshift was facilitated by moving house to a cheaper area. For example, Lisa and her partner Paul, mentioned above, moved from a large house in Queensland to a small house in a relatively inexpensive outer Melbourne suburb five years prior to interview. Savings on the cost of their home and the lower maintenance costs of a smaller dwelling, meant that they had less need for income. Likewise, Sandra, mentioned above also, had purchased a house in a small town 50 km north west of Melbourne. By doing so, she was able to afford a comfortable home with a minimal mortgage, a key factor that allowed her to reduce her paid working hours. Similarly, Sharon (aged 56), who had progressively reduced her paid working hours to care for her son, ill partner, and late father, strongly equated home ownership with financial security and was planning to now swap her currently mortgaged dwelling for a cheaper, low maintenance house that she could purchase outright. For all these women, and other participants, containing the cost of servicing a mortgage facilitated their reduction in paid working hours and their investment of time in providing care to family members.

Home ownership and geographical location also significantly influenced various aspects of consumption after downshifting, while household consumption was itself entangled with imperatives of informal care. For example, ready access to public transport and retail centres influenced the use of private vehicles for regular activities such as shopping and visiting relatives. While vehicle use for regular non-holiday travel decreased for some participants, it increased for others due to the way that they invested their time. Sandra, for example, reported that while she used public transport to travel to her part time job at a nearby aged care facility, she used her car more in order to visit and care for her distantly located aging parents. The opportunity for participants to use public transport or to walk in order to access retail or community services, was clearly dependent on the location of their residences in relation to service infrastructure and to the homes of family and friends.

Importantly, the broader impacts of the downshifting experience on household consumption patterns differed markedly for more and less wealthy households (Table 4). This was most evident in leisure activities, an area of discretionary expenditure. More wealthy households reported either undertaking more leisure travel (by road and air) due to having more time available or retaining their pre-downshifting consumption patterns. Moreover, participants from low income households were clearly constrained by lack of funds and reported reduced leisure travel and, in some cases, reduced social activity outside the home. Sharon, for example, mentioned above, reported that she could no longer afford leisure activities such as going to the theatre. Household income thus had clear implications in terms of the care-giving experience, with less wealthy downshifters less able to affordably balance caring responsibilities with rest and recreation.

Food preparation was a further terrain where consumption and unpaid informal work was closely intertwined. Food purchasing and meal preparation was the only area of consumption and household work to show a consistent pattern of change among participants after they reduced their paid working hours. However, this change was a source of both pleasure and increased household duties – with these duties unfolding along gender lines. Almost all participants, regardless of income or carer responsibilities, reported undertaking more food preparation at home. The need to be thriftier in food purchasing was given as a reason for this by seven of the ten participants, and some interviewees had changed to shopping at discount supermarkets where fresh food was less expensive. Christi, mentioned above, explained that reduced working hours meant that her and her family were less likely to purchase take-away food; and she described the pleasure she felt when family members complimented her home cooked meals. Maria (aged 45), who left well paid professional employment to join her partner in Bendigo, explained that she now needed to the consider the cost of food more carefully but felt more in control of the household and able to ensure meals were fresh and healthy. Unsurprisingly, increased meal preparation predominantly fell to women within downshifting households, while gender was a factor also in related household domains. Two participants, for example, reported that their male partners were now growing fresh vegetables - a welcome and important component of their diet post-downshifting. These experiences suggested that there could well be a 'double dividend' (Jackson 2005) to reduced paid working hours at least in relation to food, given participants readily linked home cooked meals with quality of life as well as cost-saving. However, from the perspective of gendered labour, a dividend appears less clear-cut.

In summary, our qualitative research with the ten interview participants suggested that the capacity to provide care for family members (and, in some instances, for oneself) was often a central motivation in reducing paid working hours. Carer obligations and household labour also framed the subsequent everyday experience of downshifting; an experience entwined with housing and financial security and often played out in the realm of everyday consumption. As such, concerns around the environmental impacts of consumption were largely absent in the decision of participants to downshift, with contradictory results in terms of post-downshifting expenditure. These findings mirror those of both survey-based and qualitative research into downshifters in Sweden (Nässén and Larsson 2015), Germany (Buhl and Acosta 2016), and Switzerland (Hanbury et al. 2019).

5. Conclusion

Our research into the relationship between downshifting, paid working hours, unpaid care-giving, and consumption focussed on two key questions; the first concerning the relationship between carer roles, reduced paid working hours, and income; and the second concerning the likely consequences of carer roles and reduced paid working hours for household consumption. Our quantitative analysis found clear connections between unpaid caring, paid working hours and income. The fluctuations in paid working hours of women between the ages of 40 and 60 compared with the more stable paid working hours of men of similar ages is likely to reflect the higher portion of women in informal (unpaid) carer roles. While two thirds of all informal carers in Australia are women, the likelihood of carer responsibilities increases with age and this may explain the drop off in paid working hours of women over the age of 55. We found that both women and men in carer roles had a lower income than those of a similar age who were not carers. As income is closely bound up with consumption, these patterns could have important environmental consequences and our qualitative study provided some insights into the factors at play when people transition to shorter paid working hours and ostensibly have more time but less income.

Our qualitative snapshot of the motivations for downshifting, of downshifter housing status, and of how consumption in the areas of food, transport and leisure changed after downshifting, indicates a complex picture shaped by wealth, financial security, and carer responsibilities. Reducing paid working hours was often associated with increased unpaid carer roles, it was also related to housing security but did not appear to reduce consumption in a straightforward way. For more wealthy participants, time freed up by reduced paid working hours was invested in leisure activities involving road and air travel, activities with high environmental impacts. By contrast, food provisioning appeared to be a key area where our predominantly female participants were investing time in activities with a lower environmental consequence, as preparing and consuming food at home was likely to have lower impacts than their former reliance on take-away food. Activities such as shopping and preparing food were commonly explained in terms of the need to be thriftier but some participants found the preparation and sharing of meals to be personally rewarding. However, it should be noted also that food provisioning links strongly with gendered care tasks and the maintenance of family relationships (Lindsay and Maher 2013). Above all, consumption activities took place, for many participants, in the context of having shifted from paid working hours to the unpaid provision of informal care to family members.

While some studies of downshifters have noted parental carer roles as a motivator, our findings relating to the wider range of carer roles that coalesce around working age women who reduce their paid working hours add further significant detail to our understanding of the socio-cultural dynamics of downshifting. When the insights from our qualitative interviews are combined with our analysis of national census data and summary findings of the national survey on Disability, Ageing and Carers in Australia (ABS, 2016a), our study suggests that downshifting in the 40–59 age group in Australia is likely to include a large portion of informal carers who are predominantly women. While this age group includes parents caring for young children, it also includes those caring for adult children, grandchildren, aging partners and older relatives (Williams and Nadin, 2012, Van Houtven et al., 2013, Horsfall and Dempsey, 2015). These carer roles are more likely to be experienced by women but they become more likely for both women and men as they age. We argue that the neglect of gendered patterns of paid work and unpaid care work is a major oversight in the literature on downshifting, which has tended to focus on the benefits for social wellbeing and environmental sustainability, without acknowledging the wider structural patterns that may undercut the quality of the downshifting experience. These include the different position of men and women in relation to both the paid labour market and unpaid domestic labour, including care tasks. The gendered character of work and care is further influenced by financial and housing security. While we set out to study the relationship between voluntary reduction in paid working hours and themes of care-giving and consumption, our findings problematise the voluntary character of such decisions, suggesting more complicated socio-emotional dynamics underpinning both the decision to reduce paid working hours and the subsequent experience, particularly for women. It is well established that gendered inequalities in the paid labour market and limited state provision of care mean that women are more likely than men to decrease paid labour when care is needed at home (Pocock, 2005, Maher et al., 2008, Lilly et al., 2010).

Surprisingly, the link between reducing paid working hours, gender and care is not made sufficiently explicit in existing studies of downshifting. Chhetri et al.’s (2009) large sample survey of downshifters in South East Queensland, for example, found that women were only slightly more likely to downshift than men, although one of the most common reasons given was to spend more time with one’s family (and one of the socio-demographic clusters they identified among downshifters was dominated by single mother households). Further, Chhetri at al. found that, overall, women were more likely to downshift by stopping paid work or reducing their working hours, while men were more likely to downshift by changing careers or starting a new business. Similarly, Kennedy et al. (2013) found that downshifting was strongly related to household structure, with downshifter households were more likely than non-downshifters to have children. Downshifters in their study also indicated that the desire to spend more time with children was a motivator for their decision, but this was not further investigated. Finally, those studies that have examined carer roles in more detail have tended to focus on parental care and thus neglected other forms of informal care that we have identified here (Stone, 2010, Williams and Nadin, 2012).

Given that the theme of care-giving appeared to be implicit across the range of downshifter studies we reviewed, and that our own study showed that it can assume a range of forms, a different conceptual framing may be needed to unpack the complexities of carer roles and reduced paid working hours and their implications for sustainable consumption. Rather than focus on lifestyle choices, as in the downshifters literature, we argue that it is more productive to understand this phenomena, and its contingent changes to consumption practices, through the lens of care, or by “thinking through care” (Puig de la Bellacasa 2017) and understanding care as a socio-material relation (Power 2019). For example, investing time in food preparation and managing household energy efficiencies can all be considered as practices of care that also reduce the household environmental footprint. The significance of home ownership in enabling carer roles is another example. The connections we have identified around reducing paid working hours, caring labour and consumption also signal potential areas of overlap in government policy, such as public transport and home-based support for informal carers. Practices of care feature in many social and environmental policy contexts, but areas of overlap between the two are rarely considered (Kronsell and Stensöta 2015).

Thinking through care may help to position household consumption practices in relation to environmental resource use, and help also to identify a range of policy initiatives that support practices of care that contribute to environmentally and socially sustainable forms of consumption. Our findings support the argument of Nässén and Larsson (2015) that reducing paid working hours will not necessarily lead to more sustainable household consumption in the absence of policy levers such as environmental taxes or public transport infrastructure or subsidies. Indeed, travel associated with both daily activities and with leisure is a key area for policy attention in working to reduce the environmental impacts of downshifters, with different strategies required for households in different wealth categories and with differing carer obligations. While our research was motivated by concern with the consequences of reducing paid work for household consumption, the theme of care emerged as critical for understanding this phenomenon. It seems likely that care-giving in the home and beyond shapes many other practices that carry environmental consequences, suggesting the need for more concerted research on the potential connections between care for humans and care for environment.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ruth Lane: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft. Dharmalingam Arunachalam: Formal analysis, Visualization. Jo Lindsay: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Kim Humphery: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgements

The research reported on in this paper was supported by the Faculty of Arts at Monash University and by Australian Research Council grant DP130100813 through RMIT University. The authors would like to thank Kaye Follett for her research assistance and the ten interview participants for their time and hospitality.

Contributor Information

Ruth Lane, Email: ruth.lane@monash.edu.au.

Dharmalingam Arunachalam, Email: dharma.arunachalam@monash.edu.

Jo Lindsay, Email: Jo.lindsay@monash.edu.

Kim Humphery, Email: kim.humphery@rmit.edu.au.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics . Australian Bureau of Statistics; Canberra: 2006. 2006 CENSUS. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics . Australian Bureau of Statistics; Canberra: 2011. 20011 CENSUS. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016a. Disability, Ageing and Carers, Aust 2015, Catalogue 4430.0, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016b. TableBuilder, User Guide, Catalogue 1406.0.55.005, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics . Australian Bureau of Statistics; Canberra: 2016. 2016 CENSUS. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer J.M., Sousa-Poza A. Impacts of informal caregiving on caregiver employment, health, and family. J. Populat. Ageing. 2015;8:113–145. [Google Scholar]

- Bittman M., Ironmonger D. Valuing time: a conference overview. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011;101(2):173–183. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9640-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, S., 2019. Caring in domestic spaces: Inequalities and housing. The new politics of home: Housing, gender and care in times of crisis, pp.39-62.

- Buhl J., Acosta J. Work less, do less? Sustain. Sci. 2016;11(2):261–276. doi: 10.1007/s11625-015-0322-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burningham K. The significance of relationships. Nature. Energy. 2017;2(12):914–915. doi: 10.1038/s41560-017-0056-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chhetri P., Stimson R.J., Western J. Understanding the downshifting phenomenon: a case of south east Queensland, Australia. Australian J. Soc. Issues. 2009;44(4):345–362. 10.1002/j.1839-4655.2009.tb00152.x. [Google Scholar]

- Cox R. Gendered spaces of commoditised care. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2013;14(5):491–499. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2013.813580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craig L., Mullan K. Parenthood, gender and work-family time in the United States, Australia, Italy, France, and Denmark. J. Marriage Family. 2010;72:1344–1361. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alisa G., Cattaneo C. Household work and energy consumption: a degrowth perspective. Catalonia’s case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2013;38(Supplement C):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.11.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De La Bellacasa M.P. University of Minnesota Press; 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. [Google Scholar]

- Druckman A., Buck I., Hayward B., Jackson T. Time, gender and carbon: A study of the carbon implications of British adults' use of time. Ecol. Econ. 2012;84:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Etzioni, A., Taylor-Gooby, P., 1998. Voluntary simplicity: characterization, select psychological implications, and societal consequences. J. Econ. Psychol. 19(5), 619-652.

- Fisher B., Tronto J.C. Towards a Feminist Theory of Care. In: Abel E.K., Nelson M.K., editors. Circles of care: Work and identity in women's lives. State University of New York Press; Albany NY: 1991. pp. 36–54. [Google Scholar]

- Flood S.M., Hill R., Genadek K.R. Daily temporal pathways: a latent class approach to time diary data. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018;135(1):117–142. doi: 10.1007/s11205-016-1469-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronow J., Warde A., editors. Ordinary Consumption. Routledge; London and New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Groves C., Henwood K., Shirani F., Butler C., Parkhill K., Pidgeon N. Energy biographies: narrative genres, lifecourse transitions, and practice change. Sci. Technol. Human Values. 2016;41(3):483–508. doi: 10.1177/0162243915609116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, C., Mail, E., 2003. Downshifting in Australia A sea-change in the pursuit of happiness (Discussion Paper Number 50). The Australia Institute, Retrieved from http://www.tai.org.au/node/913.

- Hanbury H., Bader C., Moser S. Reducing Working hours as a means to foster low(er)-carbon lifestyles? An exploratory study on Swiss employees. Sustainability. 2019;11(7):2024. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs, P., Gilleard, C., 2016. Personhood, identity and care in advanced old age, first ed. Bristol University Press.

- HILDA (The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia), 2016, Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 14, Survey Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research The University of Melbourne, Commonwealth of Australia.

- Hitchings R., Collins R., Day R. Inadvertent environmentalism and the action–value opportunity: reflections from studies at both ends of the generational spectrum. Local Environ. 2015;20(3):369–385. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2013.852524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horsfall B., Dempsey D. Grandparents doing gender: Experiences of grandmothers and grandfathers caring for grandchildren in Australia. J. Sociol. 2015;51:1070–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova D., Stadler K., Steen-Olsen K., Wood R., Vita G., Tukker A., Hertwich E.G. Environmental impact assessment of household consumption. J. Ind. Ecol. 2016;20(3):526–536. doi: 10.1111/jiec.12371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson T. Live better by consuming less?: Is there a “double dividend” in sustainable consumption? J. Ind. Ecol. 2005;9(1–2):19–36. 10.1162/1088198054084734. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson T. Earthscan; London and Washington DC: 2011. Prosperity Without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. [Google Scholar]

- Kallis G. Radical dematerialization and degrowth. Philos. Trans. Roy. Soc. A. 2017;375(2095):1–13. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2016.0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallis G., Kalush M., O’Flynn H., Rossiter J., Ashford N. “Friday off”: reducing working hours in Europe. Sustainability. 2013;5(4):1545. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy E.H., Krahn H., Krogman N.T. Downshifting: an exploration of motivations, quality of life, and environmental practices. Sociol. Forum. 2013;28(4):764–783. doi: 10.1111/socf.12057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kronsell, A., Stensöta, H.O., 2015. The green state and empathic rationality. In: Backstrand, K., Stensöta, H.O. (Eds.), Rethinking the Green State: Environmental governance towards climate and sustainability transitions. Oxon and New York: Routledge, pp. 225-240.

- Lindsay, J., Maher, J.M., 2013. Consuming Families: Buying, Making, Producing Family Life in the 21st Century, London and New York, Routledge.

- Lindsay J., Lane R., Humphery K. Geograph. Res. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1111/1745-5871.12396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly M.B., Laporte A., Coyte P.C. Do they care too much to work? The influence of caregiving intensity on the labour force participation of unpaid caregivers in Canada. J. Health Econ. 2010;29(6):895–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher J.M., Lindsay J., Franzway S. Time, caring labour and social policy: understanding the family time economy in contemporary families. Work Employ Soc. 2008;22(3):547–558. [Google Scholar]

- Miller D. 1st ed. Polity Press; Cambridge: 1998. A Theory of Shopping. [Google Scholar]

- Nässén J., Larsson J. Would shorter working time reduce greenhouse gas emissions? An analysis of time use and consumption in Swedish households. Environ. Plann. C: Government Policy. 2015;33(4):726–745. doi: 10.1068/c12239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters G.P., Marland G., Le Quéré C., Boden T., Canadell J.G., Raupach M.R. Rapid growth in CO2 emissions after the 2008–2009 global financial crisis. Nat. Clim. Change. 2011;2:2. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock, B., 2005. Work-life ‘balance’ in Australia: Limited progress, dim prospects. Asia Pacific J. Human Resources, 43(2), 198-209. doi:10.1177/1038411105055058 (Pocock, B., 2005. Work/care regimes: Institutions, culture and behaviour and the Australian case. Gender, Work & Organization, 12(1), pp.32-49).

- Power A., Hall E. Placing care in times of austerity. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2018;19(3):303–313. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2017.1327612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Power E.R. Assembling the capacity to care: Caring-with precarious housing. Trans. Inst. Brit. Geogr. 2019;44(4):763–777. doi: 10.1111/tran.12306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pullinger M. Working time reduction policy in a sustainable economy: Criteria and options for its design. Ecol. Econ. 2014;103:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rau H., Edmondson R. Time and Sustainability. In: Fahy F., Rau H., editors. Methods of Sustainability Research in the Social Sciences. SAGE Publications; London: 2013. pp. 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Schor Juliet. Basic Books; New York: 1998. The overspent American: Upscaling, downshifting and the new consumer. [Google Scholar]

- Schor, Juliet, 2001. Voluntary Downshifting in the 1990s. In: Stanford, J., Taylor, L., Houston, E. (Eds.), Power, Employment, and Accumulation: Social Structures in Economic Theory and Practice. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, pp. 66–79.

- Schor Juliet. Sustainable Consumption and Worktime Reduction. J. Ind. Ecol. 2005;9(1–2):37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Shirani F., Groves C., Parkhill K., Butler C., Henwood K., Pidgeon N. Critical moments? Life transitions and energy biographies. Geoforum. 2017;86:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stone W. Swinburne University; 2010. Downshifter families' housing and homes: An exploration of lifestyle choice and housing experience. PhD thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Tronto J.C. Routledge, Chapman and Hall; New York and London: 1993. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven C.H., Coe N.B., Skira M.M. The effect of informal care on work and wages. J. Health Econ. 2013;32:240–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenhofer D., Smetschka B., Akenji L., Jalas M., Haberl H. Household time use, carbon footprints, and urban form: a review of the potential contributions of everyday living to the 1.5°C climate target. Current Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018;30:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C.C., Nadin S. Work beyond employment: representations of informal economic activities. Work Employ Soc. 2012;26:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Williams M.J. The possibility of care-full cities. Cities. 2020;98 [Google Scholar]