Abstract

The first cases of COVID19 in the Maldives was reported on 7th March 2020 with a total of 13 cases by 27th March from number of resort islands and were confined to the islands in which the cases were detected. This report describes the clinical course and management of the first severe case that required intensive care. Treatment strategy adopted was supportive and patient improved wit timely symptomatic management. This case highlights the importance of epidemiological surveillance and active case finding to detect and diagnose the case at an early stage for appropriate clinical management for positive outcomes in high risk groups.

1. Introduction

The novelty of COVID-19 has prompted documentation of clinical observations and experience in the management of COVID-19 cases in different settings. This case describes the clinical course and management of the first hospitalised case of COVID -19 in Maldives, a small island setting with limited medical resources.

2. Case presentation

The patient, a 69-year-old male, had travelled to Maldives from Italy – this was a high risk country as designated by the Health Protection Agency (HPA), the department leading the COVID -19 response in Maldives. The patient, who presented to the resort doctor within three days of arrival with a history of symptoms suggestive of COVID -19, was identified through the surveillance mechanism instituted as a core feature of the pandemic preparedness and response to COVID -19 in Maldives. He was assessed and taken to an isolation facility as a suspected case of COVID -19. He was tested for SARS-nCOV2 with RT-PCR assay returning a positive result, while tests were negative for Influenza A and B. At the time of detection, the patient had a fever for two days with no history of cough or shortness of breath, had no known comorbidities and was not on any medication. Physical examination recorded a temperature of 100.8 °F, and other vital signs normal. The case was then reported to the HPA.

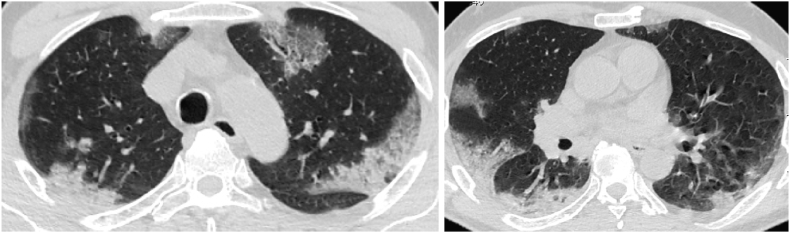

The patient's condition rapidly deteriorated with dyspnea, on day five of symptom onset, and was transported to the island of Male’ to the designated intensive care unit (ICU) for COVID -19, with the working diagnosis of COVID -19 with bilateral pneumonia. Lung auscultation showed crepitation in the interscapular and infrascapular regions on both lungs. A chest x-ray showed bilateral, peripheral ground glass opacities more evident in both bases, consistent with the changes in respiratory status (Fig. 1). At this time, the treatment strategy was supportive and management was consistent with the interim guidance of World Health Organization on clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected [1]. Over the first six days of ICU admission, despite increasing oxygenation, maintaining oxygen saturation was difficult and varied between 89 and 94% with oxygenation at 3 lit/min. The patient continued to have persistent fever and developed diarrhoea during this period. Computerised tomography (CT) of chest on day three of ICU admission showed bilateral, multifocal peripheral ground glass opacification and consolidation (Fig. 2), consistent with the patient's respiratory status. Case management included combination of antivirals Lopinavir, Ritonavir and Oseltamivir [2], and prophylactic treatment with a quinolone was started while awaiting results of culture sensitivity. The decision to start quinolone was based on the assumption of hospital acquired secondary infection, the most common of which are pseudomonas and klebsiella that are sensitive to quinolones in the hospital in which the patient was being treated. Complications emerged from day three of ICU admission and were managed with supportive treatment, including premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) and electrolyte imbalances. The patient improved with the antiviral combination and supportive treatment protocol. With reported negative results for the second test, patient was discharged on day 15 of onset.

Fig. 1.

Chest radiograph in a 69-year-old male with COVID -19 infection on day 3 of symptom onset: demonstrates bilateral peripheral ground glass opacities more evident in both bases.

Fig. 2.

Unenhanced, thin-section axial images of the lungs in a 69-year-old male COVID-19 patient with a positive RT-PCR (A–B) on day 7 of symptom onset: bilateral, multifocal peripheral GGO and consolidation. No pleural effusion.

For COVID -19 testing, clinical specimens (throat swabs and sputum) were tested with rRT-PCR assay with SarbecoV E-gene plus EAV control and Modular Wuhan CoV RdRP gene with reported sensitivity of 5.2 copies per reaction [95%] and 3.8 copies per reaction [95%] respectively. The initial specimen taken on day three of symptom onset was positive for 2019–nCoV. The cycle threshold value [Ct] was 25.664 E gene. A second assay was run with the Modular Wuhan CoV RdRP gene resulting positive with a Ct value of 26.9 gene indicating high levels of virus in these specimens. The same approach was used to ascertain recovery on day 14 of symptom onset and a repeat test was done 24 hours later as per the standard protocol for COVID -19 in Maldives. Serology on day 21 of symptom onset, was positive for IgM and IgG antibodies.

The radiological finding in this case was consistent with the respiratory status observed. The radiological pictures of chest x-ray and CT observed in this case are consistent with those reported in the emerging literature [3].

3. Discussion

The patient was at high risk of severe disease, being an elderly person of 69 years, but had no comorbidities. The clinical findings are consistent with those reported in literature, with relatively late onset of dyspnea, on day five of symptom onset, anaemia, dyselectrolytema and cardiac injury [4,5]. The treatment protocol evolved during the course of the case management. A supportive treatment regimen with a combination of antivirals [6] and antibiotics resulted in rapid improvement clinically and a positive patient outcome. Oxygenation was managed with high flow nasal cannula with the target SpO2 of 94% [7] and was central to the clinical management. The observation of arrhythmias is likely associated with hypocalcemia [8]. During the illness, the patient also developed anemia, which has been reported in some of the more severe COVID-19 cases [9]. In this case, the anemia improved with clinical improvement, without any specific intervention. However, given the high prevalence of thalassemia carriers among the population (16%–18%) [10], management of anemia will need careful consideration among local patients.

Epidemiological investigation showed travel history from a country with COVID -19 community spread and it is likely that the patient was exposed to infection from their last travel destination. The case was, classified as an imported case of COVID -19 to Maldives. In conclusion, the clinical and biochemical findings of the imported severe case of COVID -19 in Maldives is consistent with other reported findings in the literature. Prompt oxygenation and supportive management proved effective in producing positive clinical outcomes. The surveillance and active case finding measures instituted in the country allowed for early diagnosis that allowed timely treatment and recovery of the case.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Moosa Hussain: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft. Mohamed Ali: Investigation, Validation. Mohamed Ismail: Investigation, Validation. Mohame Soliman: Investigation, Validation. Milza Muhsin: Writing - original draft, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Aminath Nazeer: Writing - original draft, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Maeesha Solih: Investigation. Aminath Arifa: Investigation. Ali Latheef: Writing - review & editing. Ahmed Ziyan: Investigation, Validation. Ahmed Shaheed: Investigation, Validation. Nazla Luthfee: Investigation, Validation. Nazla Rafeeq: Investigation, Validation. Aishath Shifaly: Investigation, Validation. Sheena Moosa: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 13 March 2020. Clinical Management of Severe Acute Respiratory Infection (SARI) when COVID-19 Disease Is Suspected: Interim Guidance. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velavan T.P., Meyer C.G. The COVID‐19 epidemic. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2020. Mar;25;3:278. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simpson S., Kay F.U., Abbara S., Bhalla S., Chung J.H., Chung M., Henry T.S., Kanne J.P., Kligerman S., Ko J.P., Litt H. Radiological society of North America expert consensus statement on reporting chest CT findings related to COVID-19. Endorsed by the Society of Thoracic Radiology, the American College of Radiology, and RSNA. Radiol.: Cardiothorac. Imag. 2020 Mar 25;2(2) doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anesi G.L., Bloom A. 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): critical care issues. UptoDate. Apr 24. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lippi G., South A.M., Henry B.M. Annals express: electrolyte imbalances in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2020 May;57(3):262–265. doi: 10.1177/0004563220922255. 0004563220922255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D., Liu W., Wang J., Fan G., Ruan L., Song B., Cai Y., Wei M., Li X. A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 May 7;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poston J.T., Patel B.K., Davis A.M. Management of critically ill adults with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 Mar 26 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Q, Sun J, Zhang W, Zou L, Liu Y, Li J, Kan X, Dai L, Yuan S, Yu W, Xu H. Serum Calcium as a Biomarker of Clinical Severity and Prognosis in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: a Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Cardona-Ospina J.A., Gutiérrez-Ocampo E., Villamizar-Peña R., Holguin-Rivera Y., Escalera-Antezana J.P., Alvarado-Arnez L.E., Bonilla-Aldana D.K., Franco-Paredes C., Henao-Martinez A.F., Paniz-Mondolfi A. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trav. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020 Mar 13:101623. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waheed F., Fisher C., Awofeso A., Stanley D. Carrier screening for beta-thalassemia in the Maldives: perceptions of parents of affected children who did not take part in screening and its consequences. J. Community Genet. 2016 Jul 1;7:243–253. doi: 10.1007/s12687-016-0273-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]