Abstract

PURPOSE:

The purpose of this study was to analyze the diagnostic and therapeutic approach of five cases with optic disc pit (ODP) maculopathy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This was a retrospective study of five patients diagnosed with ODP maculopathy. Four of these cases had unilateral involvement, whereas one case had bilateral findings. The medical notes of these individuals were reviewed in order to record the presenting symptoms, clinical signs, visual acuity (VA), imaging, management, and the final visual outcome on their last follow-up appointment.

RESULTS:

The first patient (53-year-old female) underwent a left pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) combined with inner retinal fenestration, endolaser, and perfluoropropane (C3F8) gas tamponade and her VA improved from 6/24 to 6/9 Snellen. A focal retinal laser treatment was carried out on our second patient leading to decrease of the subretinal fluid but had a poor visual outcome due to the underlying secondary glaucoma from iris melanoma treatment in the past. The third patient was an asymptomatic 7-year-old girl in which the maculopathy resolved spontaneously without any surgical intervention with a final VA of 6/5. The fourth and fifth patients were asymptomatic with good vision in both eyes and were, therefore, only monitored with follow-ups.

CONCLUSION:

ODP maculopathy remains a challenging clinical entity for a vitreoretinal surgeon. The current management for ODP maculopathy involves surgical procedures with PPV being a common treatment of choice. Spontaneous resolution of ODP maculopathy has also been reported. Our study highlights the contrasting management that can be adopted in the treatment of ODP maculopathy, and there is not one definite treatment for this condition.

Keywords: Gas tamponade, inner retinal fenestration, laser, maculopathy, optic disc pit, vitrectomy

Introduction

Optic disc pit (ODP) consists of a rare congenital abnormality of the optic disc which may be accompanied by maculopathy leading to progressive loss of vision.[1] ODP together with optic disc coloboma, morning glory, and extrapapillary cavitation are considered as the main congenital cavitary anomalies of the optic nerve head.[2] It is characteristically described as a unilateral, oval, small, gray–white hypopigmented excavation of the optic disc, usually detected at the temporal or inferotemporal aspect of the optic disc. In some cases, it may be located centrally or along the nasal segment of the optic disc. Approximately 15% of cases are bilateral.[1,3] Histologically, an ODP is defined as a herniation of dysplastic retina into a collagen-rich excavation, extending into the subarachnoid space through a defect in the lamina cribrosa.[4] This particular anatomical defect is a common finding in all congenital cavitary optic disc anomalies leading to a nonphysiologic communication between the intraocular and extraocular spaces.[2,5] Occasionally, more than one pit can be found at a single optic disc.[6] The estimated incidence of ODP is 1 in 10,000 with no obvious gender predilection.[2,4] ODP occurrence is typically sporadic, but cases of autosomal inheritance have been reported in some families. There are no specific genetic associations with OPD formation.[7,8] The exact pathogenesis of ODP maculopathy is still unclear. It has been hypothesized that since it occurs around the third and fourth decades of life, it may be related to posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) and/or the cerebrospinal fluid. However, it has also been recorded in eyes of children with no vitreous liquefaction.[2,9] Despite the detrimental effect that OPD maculopathy may have on vision, there is currently no consensus with regard to the optimal treatment. This study presents five different cases with OPD highlighting the importance of prompt diagnosis together with a thorough and individualized approach [Table 1].

Table 1.

Patients’ information

| Gender | Ethnicity | Age | Presenting symptoms | Lens status | Initial Snellen VA | OCT findings | Therapeutic approach | Final Snellen VA | Other comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Female | Caucasian | 53 years | A 6-week history of gradual worsening of vision of her LE | Phakic | 6/24 | Serous macular detachment with subretinal fluid | PPV combined with retinal fenestration, endolaser, and perfluoropropane (C3F8) gas tamponade | 6/9 | History of left orbital fracture |

| Case 2 | Male | Caucasian | 62 years | Gradual loss of LE vision | Phakic | 6/60 | Maculopathy with considerable loss of cone cells, foveal atrophy, and some subfoveal cysts | Focal retinal laser treatment | 2/60 | Previously treated RE iris melanoma |

| Case 3 | Female | Caucasian | 7 years | Asymptomatic | Phakic | 6/5 | ODP in the temporal aspect of the optic nerve head with adjacent intraretinal fluid | Observation | 6/5 | Spontaneous resolution of intraretinal fluid |

| Case 4 | Male | Caucasian | 76 years | Asymptomatic | Phakic | 6/9 | Bilateral intraretinal fluid and macular schisis without foveal involvement | Observation | 6/9 | History of bilateral POAG |

| Case 5 | Female | Asian | 42 years | RE floater | Phakic | 6/5 | Serous retinopathy with macular detachment nasal to the fovea. Intraretinal cysts with fluid and slight cortical vitreous separation | Observation | 6/5 | Spontaneous resolution of maculopathy |

LE: Left eye, OCT: Optical coherence tomography, ODP: Optic disc pit, POAG: Primary open-angle glaucoma, PPV: Pars plana vitrectomy, RE: Right eye, VA: Visual acuity

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective study of five patients who were diagnosed with ODP maculopathy at a tertiary center. The research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all patient data were anonymized during extraction for analysis. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients. The medical notes of these individuals were reviewed in order to record the presenting symptoms, clinical signs, visual acuity (VA), imaging, management, and the final visual outcome on their last follow-up appointment. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (3D OCT-2000, Topcon Medical Systems, New Jersey, USA) was used to assess the optic disc maculopathy.

Results

Case 1

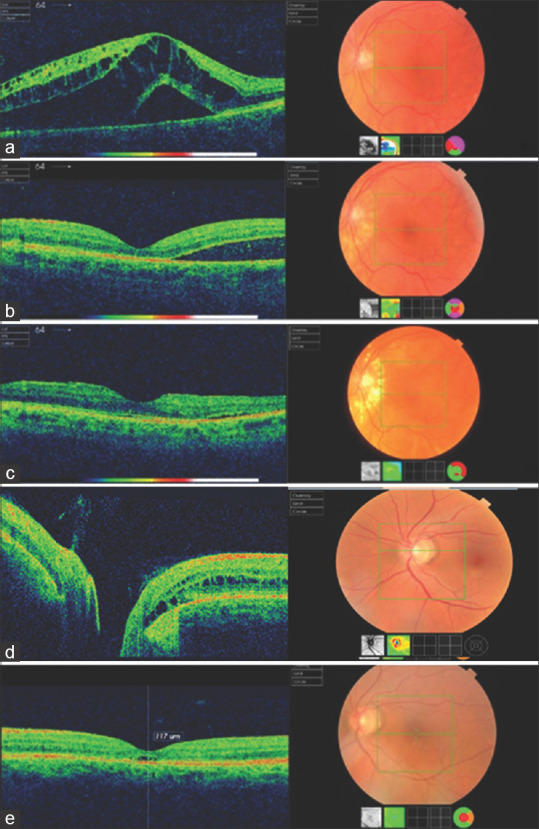

A 53-year-old Caucasian woman presented to eye casualty with a 6-week history of gradual worsening of vision of her left eye. The Snellen best-corrected VA (BCVA) of the right eye was 6/18 (unaided) improving to 6/9 (pinhole), whereas the BCVA of the left eye was 6/24 (unaided) but no improvement through pinhole. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was 16 mmHg in both eyes. There was no ocular history of surgery, but a history of left orbital fracture after a car accident was reported. There was no significant family history of ophthalmic disease. Anterior segment examination did not reveal any significant findings apart from dry eyes and a small meibomian cyst of the left eye. Both eyes were phakic with no cataracts. Dilated fundal examination showed an ODP in the left eye accompanied by some macular abnormality. An OCT scan was carried out illustrating a serous macular detachment of the symptomatic eye [Figure 1a]. No pathological findings of the fellow retina were detected. Four weeks after the initial assessment, BCVA of the left eye was 2/60, improving to 6/60 (pinhole). Fundoscopy of the affected eye showed a significant maculopathy with subretinal fluid. A left pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) combined with inner retinal fenestration, endolaser, and perfluoropropane (C3F8) gas tamponade was performed. Facedown posture was adopted postoperatively for a week. There were no complications reported from the surgery. Two months following the surgery, her BCVA improved to 6/36. On clinical examination and imaging, the central fovea was flat with substantially reduced subretinal fluid in the macular area [Figure 1b]. Six months postoperatively, the BCVA continued to improve to 6/12. OCT scan illustrated a significant regression of subretinal fluid, while the fovea was clear of fluid [Figure 1c]. On her last visit, unaided VA was 6/6 and 6/9 in the right and left eyes, respectively.

Figure 1.

(a) Optical coherence tomography scan of the left eye showing a serous macular detachment with subretinal fluid. (b) Optical coherence tomography scan carried out at a 2-month postoperative follow-up. Central fovea is flat, whereas the subretinal fluid in the macular area appears to be substantially reduced. (c) Image from optical coherence tomography scan 6 months postoperatively. The fovea is clear of fluid, and there is a significant regression of the subretinal fluid. (d) Optical coherence tomography scan showing optic disc pit maculopathy with intraretinal fluid and cystic spaces. (e) Resolution of maculopathy after focal laser application. Image on a 2-year follow-up

Case 2

A 62-year-old Caucasian gentleman with a history of previously treated right iris melanoma with secondary glaucoma and pale optic disc of the same side presented with gradual loss of left eye vision. The iris melanoma was treated with a ruthenium plaque (no iridocyclectomy was required) with no evidence of radiation retinopathy afterward. The cup–disc ratio was 0.9 in the right eye and 0.2 in the left eye. The BCVA of the right and left eyes was hand movements and 6/60, respectively. IOP was 23 mmHg in the right eye and 20 mmHg in the left. An OCT scan was carried out [Figure 1d], and the patient was also referred for electrodiagnostic assessment. Visual evoked potential to flash stimulation was grossly reduced from the right eye but was normal from the left eye. In addition, electroretinography (ERG) from the right eye were reduced and delayed to rod and cone stimulation, whereas ERG from the left eye appears to be normal. On the other hand, OCT examination revealed the presence of schisis involving the outer nuclear layer and to some extent in the inner nuclear layer and extending to involve the temporal half of the fovea. There also appeared to be an ODP with some areas of adjacent schisis to it but not extending to the fovea. OCT examination of the retinal nerve fiber layer confirmed marked optic atrophy in the right eye, but this was normal in the left eye. Overall, these findings were consistent with a left ODP maculopathy, which was quite significant since there was a loss of photoreceptors and the outer nuclear layer. However, there was no evidence of widespread retinal dystrophy in either eye.

Following a discussion with the patient, he agreed to proceed with the least invasive of the treatment options, which is focal retinal laser treatment. On his follow-up appointment after the procedure, OCT showed resolution of the schisis cavity with associated outer nuclear layer thinning and foveal thinning with some subretinal fluid under the fovea, but BCVA in his left eye was 2/60. However, the patient was not keen on any further surgical intervention [Figure 1e].

Case 3

A 7-year-old Caucasian girl was referred her optician due to a suspicious cupping of the right eye optic disc that was noted during a routine examination. The referral letter mentioned an asymmetry between the cup/disc ratios of 0.65 in the right eye and 0.45 in the left eye, respectively, accompanied by an inferior neuroretinal thinning of the right optic disc. The patient was asymptomatic, and BCVA was 6/5 in both eyes. IOP was measured at 14 mmHg in the right eye and 15 mmHg in the left eye.

Anterior segment examination was unremarkable. Dilated fundoscopy and scanning with OCT showed a right eye ODP in the temporal aspect of the optic nerve head with adjacent intraretinal fluid [Figure 2a]. No pathological findings were detected in the fellow eye. As the patient was asymptomatic and maintained good vision, she was observed and no surgical intervention was performed.

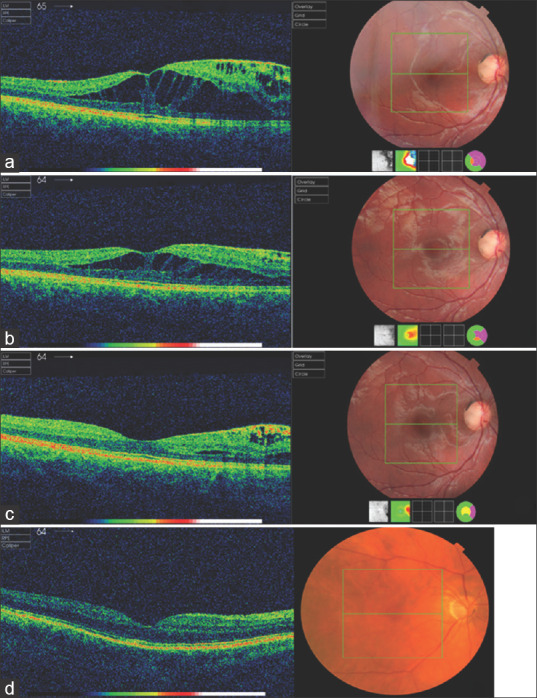

Figure 2.

(a) Optical coherence tomography scan of the right eye showing an optic disc pit in the temporal aspect of the optic nerve head with adjacent intraretinal fluid. (b) Optical coherence tomography scan, 3 months postoperatively, indicative of gradual improvement of the intraretinal fluid. (c) Last follow-up appointment. The intraretinal fluid at the optical coherence tomography scan has almost completely resolved. (d) Optical coherence tomography scan of the right eye showing optic disc pit without any related foveal abnormalities

There were gradual improvements of the intraretinal fluid on every subsequent 3-month visit [Figure 2b]. On her last follow-up appointment, the intraretinal fluid had almost completely resolved without any intervention [Figure 2c].

Case 4

A 76-year-old Caucasian gentleman with a past ocular history of bilateral primary open-angle glaucoma and cataract was referred due to the presence of bilateral intraretinal fluid. His BCVA was 6/9 in both eyes and IOP was 13 mmHg in the right eye and 12 mmHg in the left eye. The patient was asymptomatic, but his color vision was reduced (Ishihara test 3/13 in both eyes). On fundoscopy, clinical findings were compatible with bilateral ODP. OCT scan revealed macular schisis without foveal involvement [Figure 2d]. Taking into consideration the unaffected VA and based on the clinical examination and imaging findings, it was decided to continue regular monitoring before offering a surgical intervention.

Case 5

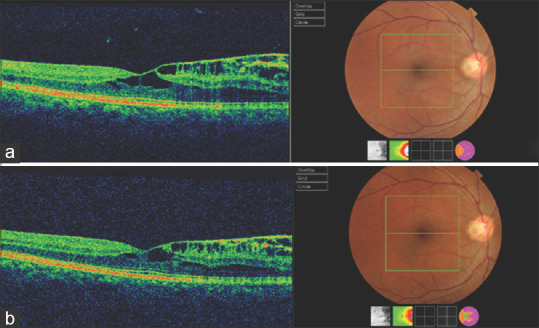

A 42-year-old Asian (Indian) woman was referred by her optician after he noticed a right ODP with associated macular changes. The patient mentioned a right eye floater but was otherwise asymptomatic. Her BCVA was 6/5 in both eyes and IOP was 17 mmHg in the right eye and 15 mmHg in the left eye. She had a thorough dilated fundus examination, and an OCT scan was also performed. The imaging findings showed a serous retinopathy with macular detachment nasal to the fovea [Figure 3a]. Intraretinal cysts with fluid and slight cortical vitreous separation could also be observed. As in case 4, this patient was not keen on any surgical intervention and she was monitored in clinic instead [Figure 3b]. Her VA remained stable at 6/9 over a 2-year follow-up.

Figure 3.

(a) Optical coherence tomography imaging findings show a right eye serous retinopathy with macular detachment nasal to the fovea. Intraretinal cysts with fluid and slight cortical vitreous separation could also be observed. (b) 2-year follow-up. Optical coherence tomography scan does not indicate any significant changes

Discussion

In most cases, ODP is asymptomatic and may be observed incidentally during a routine examination. However, it has been correlated with visual field defects and more specifically a paracentral arcuate scotoma or an enlarged blind spot.[5,6,10] Vision remains typically unchanged, but a drop in the VA may occur in a frequency ranging from 25% to 75%. A significant deterioration of vision can be observed when ODP is complicated with maculopathy. In these cases, the ODP is expected to be temporal and the VA can be 20/70 or even lower in the affected eye.[4] The term ODP maculopathy is used to describe the macular alterations (i.e., intraretinal and subretinal fluid accumulation and retinal pigment changes) detected in the context of an ODP.[5,11]

Although spontaneous resolution with consequent improvement in vision has been reported,[12,13] the prognosis is generally poor. In long-standing cases, the coexisting serous macular detachment has been correlated with lamellar or full-thickness macular holes, cystoid changes, and retinal pigment epithelium atrophy, leading to permanent visual deterioration and final VA of 20/200 or worse.[14,15]

The current mainstay for the treatment of ODP maculopathy is PPV.[16] This approach is based on the assumption that vitreous traction on the macula is the main mechanism for the development of ODP maculopathy. The induction of PVD by PPV leads to the consequent release of the vitreous traction and absorption of the subretinal fluid.[17] In most studies, a 23-gauge PPV, combined with laser application or internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling and/or gas tamponade, has been reported. The peeling is usually extended circumferentially over the macula at a distance of approximately two disc diameters around the fovea. As an adjunctive treatment to PPV, endolaser at the temporal side of the ODP can also be applied.[16] Another PPV-related technique that has been suggested involves the use of the inverted ILM-flap to cover the optic disc, excluding the fovea but including the ODP. This approach has demonstrated promising results, but the evidence remains low and further studies are needed.[18]

Intravitreal gas tamponade either alone or combined with laser has also been suggested as a therapeutic approach for ODP maculopathy.[19] Pneumatic tamponade can lead to PVD and, therefore, to release of vitreomacular traction,[17] whereas the laser photocoagulation seals the pathway of the ODP to the fovea.[20] It has been shown that the combination of gas tamponade with endolaser gives higher success rates than gas alone.[20]

Macular buckling was introduced by Theodossiadis andTheodossiadis as an alternative surgical procedure,[21] reporting a success rate of 85%. This technique offers satisfying anatomical and functional results as well as an improvement of central and peripheral visual fields, but it is technically challenging with a steeper learning curve.[22]

Further techniques have been employed for ODP maculopathy, including retinal fenestration, glial tissue removal, and autologous fibrin.[23,24,25] It has been proposed that the anatomical site of inflow into the retina appears to be topographically associated with the ODP, indicating that redirecting the flow by partial thickness retinotomies (i.e., inner retinal fenestration) enables the entrance of fluid into the vitreous cavity and not in the retina. This particular method showed a substantial improvement in VA together with a decrease in macular thickness at 12-month follow-up.[23] On the other hand, the removal of glial tissue at the temporal segment of the ODP appears to also be beneficial without recurrence of the maculopathy at a 10-year follow-up.[24] Finally, the autologous fibrin method involves the preparation of autologous fibrin from the patients' whole blood, which is eventually injected over the ODP. This step is followed by fluid-air-gas exchange. The autologous thrombocyte method is mainly combined with vitrectomy. At present, there are only a restricted number of cases available, and therefore, the current evidence remains low.[25]

This study has its limitations from the small number of patients and the retrospective nature of the study. However, as ODP cases are generally rare, the findings from this study will contribute to the pool of knowledge in the management of ODP-related maculopathy.

Conclusion

ODP maculopathy remains a challenging clinical entity for the vitreoretinal surgeons. In the vast majority of cases, if ODP is left untreated, the prognosis is generally poor and the final visual outcome unfavorable. Therefore, the current approach of ODP maculopathy involves surgical procedures with PPV (either alone or combined with other procedures) being the treatment of choice. Macular buckling offers equal results regardless of the fluid origin. Other surgical techniques include inner retinal fenestration, autologous fibrin, and glial tissue removal presenting promising results. However, spontaneous resolution of ODP maculopathy has also been reported. Clinical observation is, therefore, advocated in children who remain asymptomatic and clinically stable and maintain a good vision. Finally, this study underlines the variable management that can be adopted in the treatment of ODP maculopathy while demonstrating the need for prompt diagnosis and a patient-centered approach to management.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wiethe T. A case of congenital deformity of the optic disc. Arch Augenheilkd. 1882;11:14–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain N, Johnson MW. Pathogenesis and treatment of maculopathy associated with cavitary optic disc anomalies. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158:423–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theodossiadis GP, Panopoulos M, Kollia AK, Georgopoulos G. Long-term study of patients with congenital pit of the optic nerve and persistent macular detachment. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1992;70:495–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1992.tb02120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferry AP. Macular detachment associated with congenital pit of the optic nerve head. pathologic findings in two cases simulating malignant melanoma of the choroid. Arch Ophthalmol. 1963;70:346–57. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1963.00960050348014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kranenburg EW. Crater-like holes in the optic disc and central serous retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1960;64:912–24. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1960.01840010914013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown GC, Shields JA, Goldberg RE. Congenital pits of the optic nerve head. II. Clinical studies in humans. Ophthalmology. 1980;87:51–65. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(80)35278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stefko ST, Campochiaro P, Wang P, Li Y, Zhu D, Traboulsi EI. Dominant inheritance of optic pits. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:112–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slusher MM, Weaver RG, Jr, Greven CM, Mundorf TK, Cashwell LF. The spectrum of cavitary optic disc anomalies in a family. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:342–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rii T, Hirakata A, Inoue M. Comparative findings in childhood-onset versus adult-onset optic disc pit maculopathy. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91:429–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah SD, Yee KK, Fortun JA, Albini T. Optic disc pit maculopathy: A review and update on imaging and treatment. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2014;54:61–78. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Georgalas I, Ladas I, Georgopoulos G, Petrou P. Optic disc pit: A review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:1113–22. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1698-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benatti E, Garoli E, Viola F. Spontaneous resolution of optic disk pit maculopathy in a child after a six-year follow-up. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2018 doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta RR, Choudhry N. Spontaneous resolution of optic disc pit maculopathy after posterior vitreous detachment. Can J Ophthalmol. 2016;51:e24–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2015.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theodossiadis G. Evolution of congenital pit of the optic disk with macular detachment in photocoagulated and nonphotocoagulated eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977;84:620–31. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(77)90375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theodossiadis GP, Theodossiadis PG, Ladas ID, Zafirakis PK, Kollia AC, Koutsandrea C, et al. Cyst formation in optic disc pit maculopathy. Doc Ophthalmol. 1999;97:329–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1002194324791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalogeropoulos D, Ch'ng SW, Lee R, Elaraoud I, Purohit M, Felicida V, et al. Optic disc pit maculopathy: A review. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2019;8:247–55. doi: 10.22608/APO.2018473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talli PM, Fantaguzzi PM, Bendo E, Pazzaglia A. Vitrectomy without laser treatment for macular serous detachment associated with optic disc pit: Long-term outcomes. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2016;26:182–7. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sborgia G, Recchimurzo N, Sborgia L, Niro A, Sborgia A, Piepoli M, et al. Inverted internal limiting membrane-flap technique for optic disk pit maculopathy: morphologic and functional analysis. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2018 doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lincoff H, Yannuzzi L, Singerman L, Kreissig I, Fisher Y. Improvement in visual function after displacement of the retinal elevations emanating from optic pits. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:1071–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090080067020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lei L, Li T, Ding X, Ma W, Zhu X, Atik A, et al. Gas tamponade combined with laser photocoagulation therapy for congenital optic disc pit maculopathy. Eye (Lond) 2015;29:106–14. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theodossiadis GP, Theodossiadis PG. The macular buckling technique in the treatment of optic disk pit maculopathy. Semin Ophthalmol. 2000;15:108–15. doi: 10.3109/08820530009040001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Georgopoulos GT, Theodossiadis PG, Kollia AC, Vergados J, Patsea EE, Theodossiadis GP. Visual field improvement after treatment of optic disk pit maculopathy with the macular buckling procedure. Retina. 1999;19:370–7. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199909000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ooto S, Mittra RA, Ridley ME, Spaide RF. Vitrectomy with inner retinal fenestration for optic disc pit maculopathy. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1727–33.h. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inoue M, Shinoda K, Ishida S. Vitrectomy combined with glial tissue removal at the optic pit in a patient with optic disc pit maculopathy: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:103. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozdek S, Ozdemir HB. A new technique with autologous fibrin for the treatment of persistent optic pit maculopathy. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2017;11:75–8. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]