To the editor:

We describe a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and clinically significant kidney biopsy-proven thrombotic microangiopathy.

A 69-year-old Caucasian female with a past medical history of asthma presented to the emergency department with productive cough, fever, and shortness of breath of 2 weeks’ duration. In the emergency room, she was afebrile, with a respiratory rate of 22 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 89% on room air. Initial laboratory tests showed a normal white blood cell count, hemoglobin level, and platelet count. Inflammatory lab parameters were elevated (Table 1 ). Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection was confirmed in the patient by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay or serologic testing at our center. A chest X-ray showed bilateral diffuse patchy opacities.

Table 1.

Chronological treatment and laboratory data

| Treatment given | Day 1 |

Day 7 |

Day 16 |

Day 17 |

Day 18 |

Day 19 |

Day 20 |

Day 21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxychloroquine/low-molecular-weight heparin | Anakinra & tocilizumab | Convalescent plasma | Intubation | Dialysis started | Kidney biopsy | Eculizumab | ||

| Hemoglobin (11.5–15.5 g/dl) | 13 | 11.5 | 12.9 | 11.8 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 8.6 | 6.9 |

| Platelets (150–400 K/ul) | 203 | 142 | 85 | 14 | 97 | 37 | 21 | 27 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 2.06 | 2.49 | 4.07 | On dialysis | On dialysis |

| Fibrinogen (350–510 mg/dl) | 62 | 159 | 128 | 117 | 166 | |||

| D-dimer (<229 ng/ml DDU) | 411 | 6068 | 14,568 | 12,193 | 5927 | |||

| ADAMTS 13 activity level (>66.8%) | 43.2 | |||||||

| Alkaline phosphatase (40–120 U/l) | 137 | 118 | 292 | 296 | 194 | 212 | 204 | 294 |

| AST (10–40 U/l) | 70 | 44 | 63 | 316 | 404 | 254 | 173 | 148 |

| ALT (10–45 U/l) | 38 | 30 | 27 | 97 | 146 | 239 | 230 | 165 |

| LDH (50–242 U/l) | 459 | 1073 | 3518 | 5130 | 5183 | 4707 | ||

| C-reactive protein (0–0.40 mg/dl) | 10.35 | 2.46 | 6.85 | 18.54 | 20.73 | 13.61 | 8.02 | |

| Hep- PF 4 AB result (0.0–0.9 U/ml) | <0.6 | |||||||

| Hep- PF 4 AB interpretation | Negative | |||||||

| Schistocytes in smear | Present | Present | ||||||

| Haptoglobin (34–200 mg/dl) | <20 | <20 |

ADAMTS 13, disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; Hep, heparin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PF, endogenous protein platelet factor 4.

Medication dosages: anakinra 100 mg q6 × 8 doses; tocilizumab 400 mg i.v. × 2 doses; eculizumab 900 mg i.v.—1 dose was able to be given (patient expired).

The patient was admitted, and treatment with hydroxychloroquine, low-molecular-weight heparin, and oxygen was initiated. Over the next several days, she received anakinra and tocilizumab (dosages and details are given in Table 1). On day 12, the patient’s labs demonstrated down-trending platelets, hemoglobin, and worsening kidney function. There was concern for microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. Due to worsening hypoxemia, the patient received convalescent plasma treatment as part of an expanded access trial. On day 17, the patient was intubated due to worsening respiratory failure. In addition, the patient developed hemolysis (presence of schistocytes, undetectable haptoglobin levels, high lactate dehydrogenase level). Urinalysis showed hematuria, large blood, 30–40 red blood cells/high-power field, and 1.4 g of protein. The patient’s kidney function worsened, requiring initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy. On day 20, the patient underwent a kidney biopsy that revealed severe acute thrombotic microangiopathy with cortical necrosis (Figure 1 ). Although beta 2 glycoprotein-1 IgM levels were elevated, other laboratory and clinical features of antiphospholipid antibody were absent (Table 2 ). The disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13 (ADAMTS13) level was not low. Complement 3 and 4 were in the normal range. Heparin-induced antibody testing was negative. Coagulation parameters were normal. A kidney sonogram was negative for renal vein thrombosis and arterial clots. The patient did not have any other systemic findings of macro thrombi. Subsequent detailed complement testing revealed a low factor H complement antigen, and elevated plasma CBb complement and plasma SC5b-9 complement levels, suggesting an activation of the alternative complement pathway (Table 2). Genetic testing was not performed. Given clinical instability, plasma exchange was not performed. Instead, the patient was given a single dose of eculizumab at 900 mg on day 21. Unfortunately, the patient expired on day 23 in the setting of worsening shock.

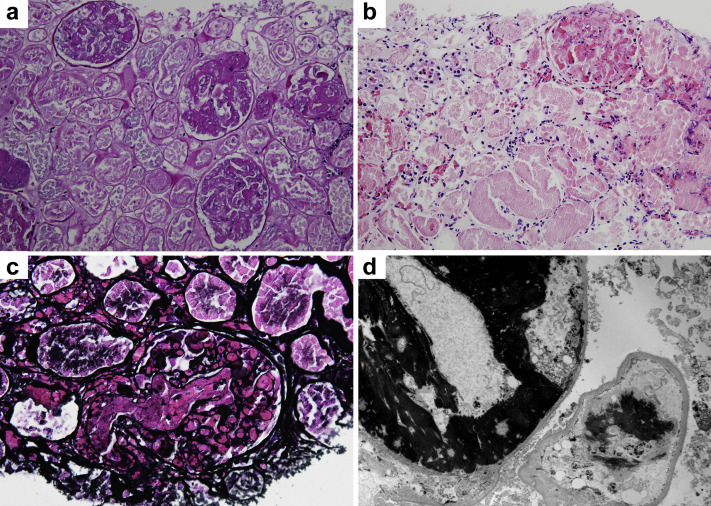

Figure 1.

Kidney biopsy findings. (a) Kidney parenchyma reveals diffuse coagulative cortical necrosis, with widespread glomerular thrombi (periodic acid–Schiff stain, original magnification ×200). (b) Glomerulus with multiple microthrombi in upper right aspect of the image and extensive coagulative necrosis of proximal tubules with ghost cells and nonviable nuclei (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×200). (c) A thrombosed glomerulus with a large thrombus in the arteriole and vascular pole (Jones methenamine silver stain, original magnification ×400). (d) Electron micrograph with extensive crosslinked fibrin deposits in capillary lumens and partially denuded capillary due to ischemia and necrosis (original magnification ×4000). To optimize viewing of this image, please see the online version of this article at www.kidney-international.org.

Table 2.

Antiphospholipid panel and complement panel

| Comprehensive complement testing with results and reference ranges |

| Serum complement total—56U/ml (30–75) |

| Serum complement C3—105 mg/dl (75–175) |

| Serum complement C4—26 mg/dl (14–40) |

| Serum factor B complement antigen—28 mg/dl (15.2–42.3) |

| Serum factor H complement antigen—22 mg/dl (23.6–43.1) |

| Plasma C4d complement—2.3 mcg/ml (<9.9) |

| Plasma CBb complement—4.4 mcg/ml (<1.7) |

| Plasma SC5b-9 complement—875 ng/ml (<251) |

| Antiphospholipid antibody testing with results and reference ranges |

| Anticardiolipin IgG—13.6 GPL (0–12.5) |

| Anticardiolipin IgM—12.5 MPL (0–12.5) |

| Anticardiolipin IgA—6.7 APL (0–12.5) |

| Beta 2 glycoprotein—1 IgG—<5 SGU (<20) |

| Beta 2 glycoprotein—1 IgM—68.6 SMU (<20) |

| Beta 2 glycoprotein—1 IgA—8 SAU (<20) |

APL, A phospholipids units; GPL, G phospholipids units; MPL, M phospholipids units; SAU, standard IgA aB2G2P1 unit; SGU, standard IgG aB2GPI unit; SMU, standard IgM aB2GPI unit.

Coagulopathy associated with SARS-CoV-2 has been widely reported.1 , 2 The profound hypoxia, inflammation, and disseminated intravascular coagulation have all been implicated as potential causes.2 There has also been a report of coagulopathy secondary to development of antiphospholipid antibodies.3 Our patient had no evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Although we cannot completely rule out antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, it is less likely to have played a role in this case, as there was no prior history of autoimmunity and no other current stigmata of evolving connective tissue disease, such as lupus, or antiphospholipid syndrome in other body systems. Transient elevation of both beta-2 glycoprotein-1 IgG and IgM can be seen in the setting of infections and drug exposures.4 Ideally, a confirmation of autoantibodies is needed at 12 weeks, which was not possible to do in this case. Collapsing glomerulopathy associated with SARS-CoV-2 has now been reported from several centers as the first described glomerular pathology in this setting.5 , 6 To our knowledge, there have been no published cases of SARS-CoV-2–associated systemic thrombotic microangiopathy. We report the first case of thrombotic microangiopathy associated with SARS-CoV-2, with presence of diffuse cortical necrosis and widespread microthrombi in the kidney biopsy. It is not clear if the virus played a direct pathogenic role or unmasked a latent complement defect (as noted in our complement testing) leading to widespread endothelial damage and micro thrombi.7

Acute kidney injury is not uncommon in patients with COVID-19.8 Causes of acute kidney injury can range from pre-renal azotemia, to acute tubular injury, to collapsing glomerulopathy.5 , 6 , 9 Physicians treating patients with COVID-19 should keep microangiopathic disease in the differential diagnosis when systemic findings of hemolysis are present along with thrombocytopenia and acute kidney injury. Earlier diagnosis could perhaps lead to prompt treatment with plasma exchange or complement pathway inhibitors.

Disclosure

KDJ serves as a consultant for Astex Pharmaceuticals and Natera. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Northwell Covid-19 Research consortium.

The Northwell Health Institutional Review Board approved this case as minimal-risk research using data collected for routine clinical practice and waived the requirement for informed consent.

References

- 1.Chng W.J., Lai H.C., Earnest A., Kuperan P. Haematological parameters in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Lab Haematol. 2005;27:15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2257.2004.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan B.E., Chong V.C.L., Chan S.S.W. Hematologic parameters in patients with COVID-19 infection. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:E131–E134. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y., Xiao M., Zhang S. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNally T., Purdy G., Mackie I.J. The use of an anti-beta 2-glycoprotein-I assay for discrimination between anticardiolipin antibodies associated with infection and increased risk of thrombosis. Br J Haematol. 1995;91:471. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb05324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaillard F., Ismael S., Sannier A. Tubuloreticular inclusions in COVID-19–related collapsing glomerulopathy. Kidney Int. 2020;98:241. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su H., Yang M., Wan C. Renal histopathological analysis of 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int. 2020;98:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caprioli J., Noris M., Brioschi S. International Registry of Recurrent and Familial HUS/TTP: genetics of HUS: the impact of MCP, CFH, and IF mutations on clinical presentation, response to treatment, and outcome. Blood. 2006;108:1267–1279. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-007252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirsch J.S., Ng J.H., Ross D.W. Acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;98:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohamed M.M.B., Lukitsch I., Torres-Ortiz A.E. Acute kidney injury associated with coronavirus disease 2019 in urban New Orleans. Kidney360. 2020;1 doi: 10.34067/KID.0002652020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]