Abstract

Background

Frailty is a multidimensional syndrome that reflects the physiological reserve of elderly. It is related to unfavorable outcomes in various cardiovascular conditions. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association of frailty with all-cause mortality and bleeding after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in the elderly.

Methods

We comprehensively searched the databases of MEDLINE and EMBASE from inception to March 2019. The studies that reported mortality and bleeding in AMI patients who were evaluated and classified by frailty status were included. Data from each study were combined using the random-effects, generic inverse variance method of DerSimonian and Laird to calculate hazard ratio (HR), and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Twenty-one studies from 2011 to 2019 were included in this meta-analysis involving 143,301 subjects (mean age 75.33-year-old, 60.0% male). Frailty status was evaluated using different methods such as Fried Frailty Index. Frailty was statistically associated with increased early mortality in nine studies (pooled HR = 2.07, 95% CI: 1.67–2.56, P < 0.001, I2 = 41.2%) and late mortality in 11 studies (pooled HR = 2.30, 95% CI: 1.70–3.11, P < 0.001, I2 = 65.8%). Moreover, frailty was also statistically associated with higher bleeding in 7 studies (pooled HR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.12–1.59, P < 0.001, I2 = 4.7%).

Conclusion

Frailty is strongly and independently associated with bleeding, early and late mortality in elderly with AMI. Frailty assessment should be considered as an additional risk factor and used to guide toward personalized treatment strategies.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction, Bleeding, Frailty, Mortality

1. Introduction

Frailty is a complex clinical phenotype that reflects an age-associated decline in reserve, responding to physiological stressors.[1] Common manifestations of frailty are slowness, reduced activity, low energy level, and unintentional weight loss.[2] Prevalence of Frailty in elderly adult ranging from 4% to 59.1% and more common in female.[3] It varied depending on the study population, age group as well as an assessment strategy.[4] Prevalence of frailty found to be higher with older age;[5] hence, frailty becomes more compelling with an aging society.

There have been over 20 tools developed to assess frailty.[6] At least one of five core domains of frailty phenotype, including slowness, weakness, low physical activity, exhaustion, and shrinking is evaluated to determine frailty status.[2] For example, Fried Frailty Index was developed from the Cardiovascular Health Study, consisting of unintentional weight loss, self-reported exhaustion, weakness, slow walking speed, and low physical activity. Frailty was defined if 3 or more mentioned criteria present[1] and was found to be independently predictive of hospitalization and death.

Frailty has been associated with increased mortality in several cardiovascular diseases.[2] Cacciatore, et al.[7] showed that chronic heart failure patients who were frail had a lower 10-year survival (6% vs. 31%). Anand, et al.[8] studied the relationship between frailty and outcomes following transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Interestingly, frailty was associated with increase both early and late mortality, HR = 2.35 (95% CI: 1.78–3.09, P < 0.001) and HR = 1.63 (95% CI: 1.34–1.97, P < 0.001), respectively. Some studies showed a connection between less aggressive management of acute coronary syndrome in frail patients.[4],[9],[10]

Dual antiplatelet is a cornerstone in AMI treatment according to 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)[11] and 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome.[12] Bleeding is one of the major complications following AMI management. Comparing risk and benefit is often time delicate, especially in the elderly population. Thus, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the associated of frailty with all-cause mortality and bleeding in elderly AMI patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

Two investigators (PP and WS) independently searched for published studies indexed in MEDLINE and EMBASE databases from inception to March 2019 using a search strategy that included the term for “frailty (and its synonyms)” and “myocardial infarction”. Only English language publications were included. A manual search for additional pertinent studies and review articles using references from retrieved articles was also completed.

2.2. Inclusion criteria

The eligibility criteria included the following: (1) prospective cohort study reporting the incidence of frailty in AMI patients. No restriction was placed on frailty criteria. (2) The primary outcome was all-cause mortality after AMI, either reported in short (< 1 year) or long term (> 1 year). The secondary outcome was significant bleeding, which defined as intracranial hemorrhage, retroperitoneal hemorrhage, hemoglobin drop ≥ 4 g/dL or any bleeding requiring blood transfusions. Studies that report either primary or secondary outcome were included. (3) Calculation of relative risk, hazard ratio, odds ratio, incidence ratio, or standardized incidence ration with 95% CI or provision of sufficient raw data for these calculations were provided.

2.3. Data extraction

A standardized data collection form was used to obtain the following information from each study: title of study, name of first author, year of study, year of publication, country, number of participants, demographic data of participants, criteria used to identify frailty, type of AMI, outcome of interest (either all-cause mortality or bleeding), and average duration of follow-up.

To ascertain the accuracy, four investigators (NK, WV, PR, JK) independently performed this data extraction process. Any data discrepancy was resolved by referring back to the original articles. The Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale was used to evaluate each study in three domains: recruitment and selection of the participants, similarity and comparability between the groups, and ascertainment of the outcome of the interest among cohort studies.[13]

2.4. Data synthesis and analysis

We performed a meta-analysis of the included studies using a random-effects model given a wide number of frailty criteria used. The extracted studies were excluded from the analysis if they did not present an outcome in each intervention group or did not have enough information required for continuous data comparison. We pooled the point estimates from each study using the genetic inverse-variance method of Der Simonian and Laird.[14] The heterogeneity of effect size estimates across these studies was quantified using the I2 statistic and Q statistic. For Q statistic, substantial heterogeneity was defined as P < 0.10. The I2 statistic rages in value from 0 to 100% (I2 < 25%, low heterogeneity; I2 = 25%–50%, moderate heterogeneity; and I2 > 50%, substantial heterogeneity).[15] A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the influence of the individual studies on the overall results by omitting one study at a time. Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot.[16] Pooled HR, sensitivity analysis, funnel plot and forest plot were performed using the Stata SE 15.1 software from StatCorp LP. Egger test was also performed using the Stata SE 15.1 software from StatCorp LP.

3. Results

3.1. Description of included studies

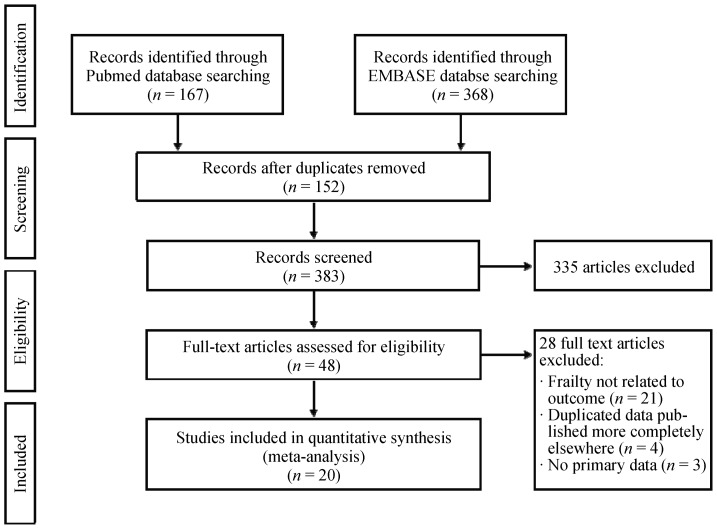

Our search strategy yielded 535 potentially relevant articles (368 articles from EMBASE and 167 articles from MEDLINE). After exclusion of 152 duplicates, 354 underwent title and abstract review. Three hundred and six articles were excluded at this stage since they were not cohort studies, and they were not conducted in patients with AMI, leaving 48 articles for full-length article review. Twenty-one articles were excluded since no report of frailty related to exceptional outcomes. Four articles were excluded due to duplicated population, and three articles were excluded because of no primary data. Therefore, twenty prospective cohort studies of AMI patients were in clouded in this meta-analysis. Figure 1 outlines the search and literature review process. The summary of the clinical characteristic of included studies is provided in Table 1. The Newcastle-Ottawa scales of the included studies are described in the supplement Table 1S.

Figure 1. Search methodology and selection process.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and summary of included studies in meta-analysis.

| Author, year | Country | Definition of frailty | N | Age (mean ± SD) | Male gender, % | Population | Proportion of frail, % | Follow-up, months |

| Batty, 2019[26] | UK | Fried Frailty Index | 280 | 81 ± 4 | 60 | NSTEMI | 27.5 | 12 (censored) |

| Blanco, 2017[27] | France | Edmonton Frail Scale | 236 | 85.9 | N/A | NSTEMI, STEMI | 20.8 | 15.67 |

| Calvo, 2018[17] | Spain | FRAIL scale | 259 | 82.6 ± 6 | 57.9 | STEMI | 19.7 | - |

| Dodson, 2016[28] | USA | Slow gait (< 0.8 m/s) | 338 | 73.6 ± 6.01 | 59.16 | NSTEMI, STEMI | 53.6 | 12 (censored) |

| Dodson, 2018[36] | USA | Frailty Point Scoring System | 12,9330 | 75.3 ± 7.7 | 60.2 | NSTEMI, STEMI | 5.3 | - |

| Ekerstad, 2018[18] | Sweden | CFS | 307 | 83.97 ± 6.63 | 51.1 | NSTEMI | 48.5 | 80.4 |

| Flint, 2018[29] | USA | Slow gait (< 0.8 m/s) | 329 | 73.3 ± 6.2 | 68.4 | NSTEMI, STEMI | 53.7 | 12 (censored) |

| Graham, 2013[30] | Canada | Edmonton Frail Scale | 183 | 75.4 | 67.2 | NSTEMI, STEMI | 30.1 | 36 (censored) |

| Herman, 2019[20] | Netherlands | VMS score | 206 | 79 ± 6.4 | 58 | STEMI | 28 | 1 |

| Kang, 2015[21] | China | Clinical Frail Scale | 352 | 74 ± 6.5 | 57.7 | NSTEMI, STEMI | 43.18 | 4 |

| Llao, 2019[22] | Spain | FRAIL scale | 531 | 84.3 ± 4 | 62.5 | NSTEMI | 27.3 | 6 |

| Nunez, 2017[31] | Spain | Fried Frailty Index | 270 | 78 ± 7 | 56.7 | NSTEMI | 35.6 | 52.8 |

| Patel, 2018[23] | Australia | Frailty Index Parameter | 3944 | 74.33 | 66.0 | NSTEMI, STEMI | 27.7 | 6 |

| Salinas, 2016[37] | Spain | SHARE-FI | 190 | 82.76 ± 4.85 | 39.5 | NSTEMI, STEMI | 37.9 | 1 |

| Salinas, 2017[24] | Spain | SHARE-FI | 234 | 82.74 ± 4.9 | 40.2 | NSTEMI, STEMI | 40.2 | 6 (censored) |

| Salinas, 2018[32] | Spain | SHARE-FI | 285 | 82.47 ± 4.77 | 60 | NSTEMI, STEMI | 38.2 | 12 (censored) |

| Sanchis, 2014[33] | Spain | Green scales | 324 | 77 ± 7 | 57 | NSTEMI, STEMI | 48 | 30 |

| Sigh, 2011[34] | USA | Fried Frailty Index | 545 | 74.72 | 69 | NSTEMI, STEMI | 21.47 | 35 |

| Sugino, 2014[25] | Japan | CSHA-CFS | 62 | 88.1 ± 2.5 | 58.1 | STEMI | 35.5 | 1 |

| White, 2015[35] | USA | Fried Frailty Index | 4996 | 73.3 | 53.8 | NSTEMI | 4.7 | 17.1 |

CFS: clinical frailty score; CSHA-CFS: Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale score; NSTEMI: non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; SHARE-FI: Survery of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe; STEMI: ST elevation myocardial infarction; VMS: veiligheids management system.

3.2. Definitions of frailty

Frailty was identified by authors using objective assessments. Various frailty-defining tools were used. Details of each tool are provided in supplement Table 2S. There was no subjective frailty, which was based on judgments of research team alone included in our meta-analysis.

3.3. Meta-analysis results

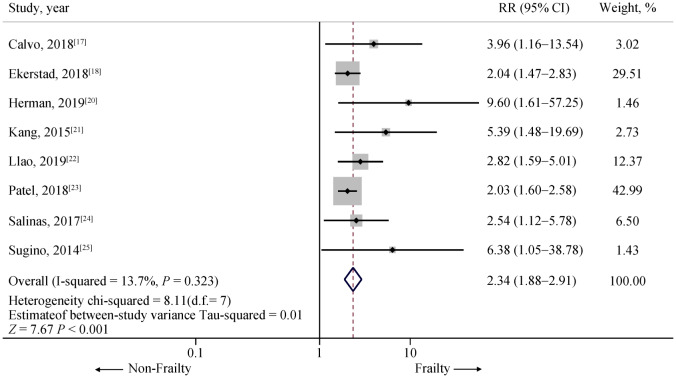

Twenty-one studies from August 2011 to February 2019 were included in this meta-analysis involving 143,301 subjects with AMI, mean age was 75.33-year-old and 60.0% were male. Ten thousand and two subjects (6.98% of total subjects) were determined as frail. Nine studies involving 5995 subjects with AMI (30.43% of subjects were frail) revealed an increased early (< 1 year) all-cause mortality among AMI patients[17]–[25] with one of nine studies[19] not achieving statistical significance. The pooled analysis demonstrated a significantly increased risk of early all-cause mortality in AMI patient who frail compared to those non-frail group, with a pooled HR of 2.07 (95% CI: 1.67–2.56, P < 0.001, I2 = 41.2%). A forest plot of this meta-analysis is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Risk of short term (< 1 year) mortality in included studies.

Summary meta-estimate calculations based on random-effects model analysis.

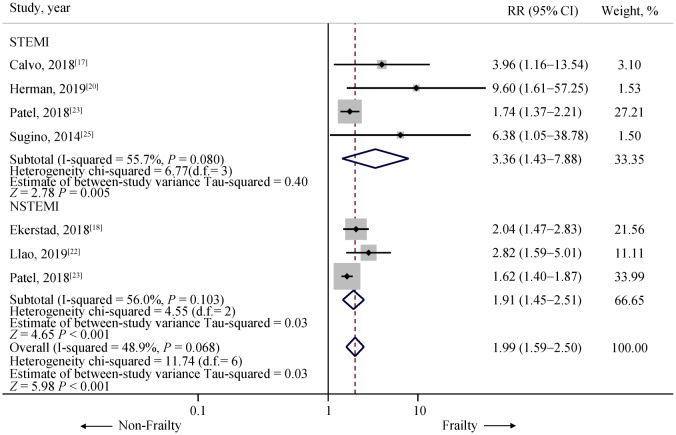

In subgroup analysis among type of AMI, four studies were included in STEMI[17],[20],[23],[25] involving 1,802 subjects (322 patients with frailty status and 1480 patients with non-frailty status). All four studies revealed statistical significantly increased early all-cause mortality among frail STEMI patients. The pooled analysis demonstrated a significant increased early all-cause mortality in frail STEMI patient compared to those without frail status (HR = 3.36, 95% CI: 1.43–7.88, P = 0.005, I2 = 55.7%). In NSTEMI cohorts, three studies were included in the analysis[18],[22],[23] involving 3507 subjects (1996 patients were frail and 1551 were non-frail). The pooled analysis again demonstrated a significant increased risk of early all-cause mortality in NSTEMI patients with frailty status compared to those without frailty status (HR = 1.99, 95% CI: 1.59–2.50, P < 0.001, I2 = 48.9%). A forest plot of this meta-analysis is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Risk of short term (< 1 year) mortality in included studies in STEMI and NSTEMI subgroup.

Summary meta-estimate calculations based on random-effects model analysis. NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

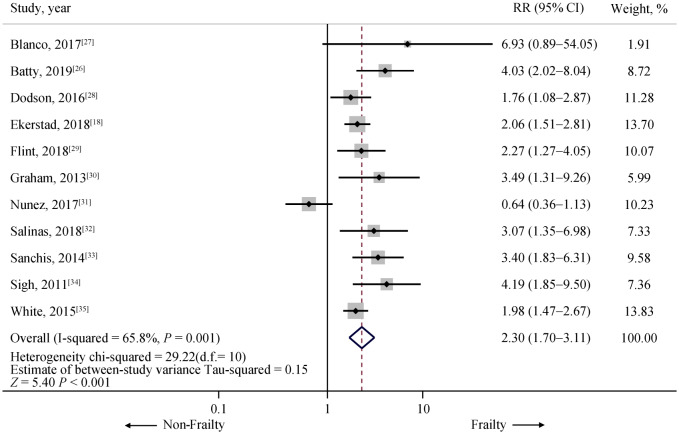

For late all-cause mortality (≥ 1 year), there were 11 studies available involving 1400 frail and 6693 non-frail patients.[18],[26]–[35] One of eleven studies did not demonstrate a statically significant association between frailty and late all-cause mortality.[31] However, the pooled analysis demonstrated a statistically significant increased risk of late all-cause in frail group compared to non-frail group with HR = 2.30 (95% CI: 1.70–3.11, P < 0.001, I2 = 65.8%). Forest plot of this meta-analysis is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Risk of long term (≥ 1 year) mortality in included studies.

Summary meta-estimate calculations based on random-effects model analysis.

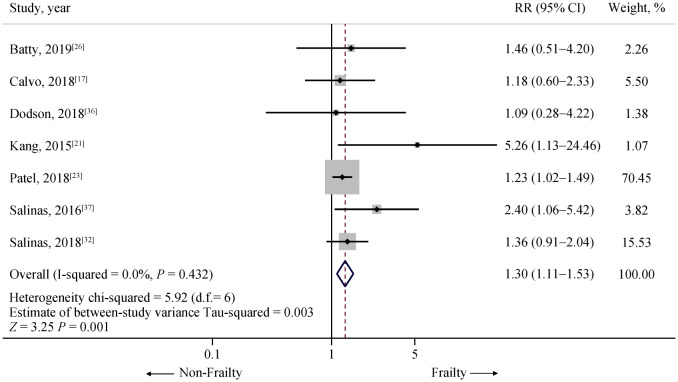

To access the association of significant bleeding as the outcome, seven studies that reported bleeding as an outcome were analyzed, involving 134,640 patients (6.24% of patients were frail).[17],[21],[23],[26],[32],[36],[37] The pooled analysis also demonstrates a statistically significant increased risk of severe bleeding in frail patients compared to non-frail patients with the pooled HR 1.34 (95% CI: 1.12–1.59, P = 0.001, I2 = 4.7%). Forest plot of this meta-analysis is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Risk of significant bleeding in included studies.

Summary of meta-estimate calculations based on random-effects model analysis.

3.4. Sensitivity analysis

To assess the stability of the results of the meta-analysis, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding one study at a time. None of the result was significantly altered, as the results after removing one study at a time were similar to that of the main meta-analysis indicating that our results were robust (Supplement Figure 1–3).

3.5. Publication bias

To investigate potential publication bias, we examined the contour-enhanced funnel plot of the included studies in assessing change in the log odd ratio of early all-cause mortality, late all-cause mortality or bleeding. The vertical axis represents studies size (standard error) while the horizontal axis represents effect size (log odds ratio). The distribution of studies on both sides of the mean was symmetrical.

4. Discussion

In our systematic review and meta-analysis, we explored the association between frailty and outcome of elderly with AMI, including early mortality, late mortality, and bleeding in 20 studies comprising 143,301 patients with frail elderly. We have made notably important observation. First, frail AMI patients have over twice as high risk of both early and late mortality than non-frail patients. The effect of frailty is even more prominent in STEMI subgroups. Second, a variety of assessment tool was used to determined frailty resulting in a wide range of prevalence of frailty in studied cohorts. However, all study observed a similar association between frailty and interested outcomes.

Frailty has become an emerging consideration in cardiovascular medicine due to the aging population. Not only AMI, but frailty also related to increased mortality in congestive heart failure, cardiac surgery as well as transcatheter aortic valve implantation.[10],[38]–[40] On the other hand, the Women's Health Initiative Study showed that patients with coronary artery disease were more likely to develop de novo frailty.[41] Thus, the American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology have emphasized that assessment of frailty is crucial in managing elderly patients with AMI.[42],[43] Intervening frailty status of patients is might be as vital as preventing and managing AMI.

Advanced age is considered a risk factor of impaired outcomes in patients with AMI and also included in well-accepted risk scores such as the GRACE risk score and TIMI risk score.[44],[45] However, the elderly population is heterogeneous and under-represented in the derivation and validation cohorts. Interestingly, Hermans, et al.[20] revealed that patients with at least one signs of frailty, according to VMS score had a nearly ten times higher risk of early mortality regardless of age and clinical characteristic. Hence, frailty assessment needs to be integrated with the prognostic score for better risk stratification, especially in the geriatric population.

The decision for invasive or conservative treatment of frail elder patients with AMI, especially NSTEMI, is frequently challenging to make. There is no recommendation or guideline specifically to AMI with frailty. Several studies observed increased bleeding risk only in frail patients who underwent catheterization, but not those treated with medical management.[36],[37],[46] Besides, major bleeding may lead to other consequences such as transfusion reaction, cessation of anti-thrombotic therapy, prolonged hospitalization, and even death.[47],[48] Randomized control trails need to be performed in frail elderly patients with AMI to determine if invasive management could be favorable in this unique population.

Despite a significant impact of frailty to AMI and other cardiovascular diseases, there is a lack of consensus of validating frailty assessment tools. In our included studies, the prevalence of frailty varied from 5.3% to 53.7%. Numerous definition and assessment score were used. All of the included frailty tools are consisted of at least one of five core domains (slowness, weakness, low physical activity, exhaustion and shrinking). Comprehensive geriatric assessment of every elderly individual before managing AMI is not realistic for daily practice; therefore, adapting most available measures according to resources and circumstance may be reasonable. Nevertheless, frailty tool that easy to use, reproducible and accurate is warranted not only for guiding AMI management and excelling outcome but also leading to further research on this critical field.

Frailty is not modifiable in an acute setting. So far, exercise is the most promising intervention in a frail elderly population.[49],[50] Unfortunately, Flint, et al.[29] revealed that patients in the frail group were less likely to be referred to cardiac rehabilitation (CR) and even with a referral, they less participated after AMI. Individualized designed of CR program that is appropriate to older adults is imperative. Other interventions to mitigate the risk of adverse outcome, especially bleeding include radial access and avoid excess dosing of anticoagulants.[51]–[54]

4.1. Limitation

We recognize that there are limitations to our meta-analysis. First, studies with different methodology and demographic data were included and thus might be potential sources of heterogeneity, but the sensitivity analysis revealed no significant alteration in the result. Second, we could not perform the subgroup analysis comparing both early mortality, late mortality, and bleeding outcome between patients who underwent invasive strategies and medical management. Finally, extracted data from included studies were not always adjusted for other variables.

4.2. Conclusion

The value of frailty as a prognostic factor of AMI in the geriatric population is well demonstrated. Frailty should be included in prognostic tools of AMI. A standardized frailty assessment tool that simple, accurate and reproducible is needed not only for clinical practice but also for future researches.

References

- 1.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afilalo J, Alexander KP, Mack MJ, et al. Frailty assessment in the cardiovascular care of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:747–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1487–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Purser JL, Kuchibhatla MN, Fillenbaum GG, et al. Identifying frailty in hospitalized older adults with significant coronary artery disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1674–1681. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buckinx F, Rolland Y, Reginster JY, et al. Burden of frailty in the elderly population: perspectives for a public health challenge. Arch Public Health. 2015;73:19. doi: 10.1186/s13690-015-0068-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Vries NM, Staal JB, van Ravensberg CD, et al. Outcome instruments to measure frailty: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cacciatore F, Abete P, Mazzella F, et al. Frailty predicts long-term mortality in elderly subjects with chronic heart failure. Eur J Clin Invest. 2005;35:723–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2005.01572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anand A, Harley C, Visvanathan A, et al. The relationship between preoperative frailty and outcomes following transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2017;3:123–132. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcw030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekerstad N, Swahn E, Janzon M, et al. Frailty is independently associated with 1-year mortality for elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:1216–1224. doi: 10.1177/2047487313490257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lupon J, Gonzalez B, Santaeugenia S, et al. Prognostic implication of frailty and depressive symptoms in an outpatient population with heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2008;61:835–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians and Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;82:E1–E27. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;23; 64:e139–e228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calvo E, Teruel L, Rosenfeld L, et al. Frailty in elderly patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;18:132–139. doi: 10.1177/1474515118796836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ekerstad N, Pettersson S, Alexander K, et al. Frailty as an instrument for evaluation of elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: A follow-up after more than 5 years. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25:1813–1821. doi: 10.1177/2047487318799438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamonangan R, Wijaya IP, Setiati S, Harimurti K. Impact of frailty on the first 30 days of major cardiac events in elderly patients with coronary artery disease undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Acta Med Indones. 2016;48:91–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermans MPJ, Eindhoven DC, van Winden LAM, et al. Frailty score for elderly patients is associated with short-term clinical outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevated myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Neth Heart J. 2019;27:127–133. doi: 10.1007/s12471-019-1240-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang L, Zhang SY, Zhu WL, et al. Is frailty associated with short-term outcomes for elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome? J Geriatr Cardiol. 2015;12:662–667. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Llao I, Ariza-Sole A, Sanchis J, et al. Invasive strategy and frailty in very elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes. EuroIntervention. 2018;14:e336–e342. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-18-00099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel A, Goodman SG, Yan AT, et al. Frailty and Outcomes After Myocardial Infarction: Insights From the CONCORDANCE Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009859. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alonso Salinas GL, Sanmartin M, et al. Frailty is an independent prognostic marker in elderly patients with myocardial infarction. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:925–931. doi: 10.1002/clc.22749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sujino Y, Tanno J, Nakano S, et al. Impact of hypoalbuminemia, frailty, and body mass index on early prognosis in older patients (>/=85 years) with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Cardiol. 2015;66:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batty J, Qiu W, Gu S, et al. One-year clinical outcomes in older patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome undergoing coronary angiography: An analysis of the ICON1 study. Int J Cardiol. 2019;274:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanco S, Ferrieres J, Bongard V, et al. Prognosis impact of frailty assessed by the edmonton frail scale in the setting of acute coronary syndrome in the elderly. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:933–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dodson JA, Arnold SV, Gosch KL, et al. Slow gait speed and risk of mortality or hospital readmission after myocardial infarction in the translational research investigating underlying disparities in recovery from acute myocardial infarction: patients' health status registry. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:596–601. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flint K, Kennedy K, Arnold SV, et al. Slow gait speed and cardiac rehabilitation participation in older adults after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008296. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham MM, Galbraith PD, O'Neill D, et al. Frailty and outcome in elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:1610–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nunez J, Ruiz V, Bonanad C, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention and recurrent hospitalizations in elderly patients with non ST-segment acute coronary syndrome: the role of frailty. Int J Cardiol. 2017;228:456–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alonso Salinas GL, Sanmartin M, et al. The role of frailty in acute coronary syndromes in the elderly. Gerontology. 2018;64:422–429. doi: 10.1159/000488390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanchis J, Bonanad C, Ruiz V, et al. Frailty and other geriatric conditions for risk stratification of older patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2014;168:784–791. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh M, Rihal CS, Lennon RJ, et al. Influence of frailty and health status on outcomes in patients with coronary disease undergoing percutaneous revascularization. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:496–502. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.961375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White HD, Westerhout CM, Alexander KP, et al. Frailty is associated with worse outcomes in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: Insights from the TaRgeted platelet Inhibition to cLarify the Optimal strateGy to medicallY manage Acute Coronary Syndromes (TRILOGY ACS) trial. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016;5:231–242. doi: 10.1177/2048872615581502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dodson JA, Hochman JS, Roe MT, et al. The association of frailty with in-hospital bleeding among older adults with acute myocardial infarction: insights from the ACTION Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:2287–2296. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alonso Salinas GL, Sanmartin Fernandez M, Pascual Izco M, et al. Frailty predicts major bleeding within 30days in elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2016;222:590–593. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Afilalo J, Eisenberg MJ, Morin JF, et al. Gait speed as an incremental predictor of mortality and major morbidity in elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1668–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee DH, Buth KJ, Martin BJ, et al. Frail patients are at increased risk for mortality and prolonged institutional care after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2010;121:973–978. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.841437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Afilalo J, Lauck S, Kim DH, et al. Frailty in older adults undergoing aortic valve replacement: The FRAILTY-AVR Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woods NF, LaCroix AZ, Gray SL, et al. Frailty: emergence and consequences in women aged 65 and older in the women's health initiative observational study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1321–1330. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alexander KP, Newby LK, Cannon CP, et al. Acute coronary care in the elderly, part I: Non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: in collaboration with the Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115:2549–2569. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.182615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. [2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation] Kardiol Pol. 2015;73:1207–1294. doi: 10.5603/KP.2015.0243. [In Polish] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fox KA, Dabbous OH, Goldberg RJ, et al. Prediction of risk of death and myocardial infarction in the six months after presentation with acute coronary syndrome: prospective multinational observational study (GRACE) BMJ. 2006;333:1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38985.646481.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morrow DA, Antman EM, Charlesworth A, et al. TIMI risk score for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A convenient, bedside, clinical score for risk assessment at presentation: An intravenous nPA for treatment of infarcting myocardium early II trial substudy. Circulation. 2000;102:2031–2037. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.17.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ekerstad N, Swahn E, Janzon M, et al. Frailty is independently associated with short-term outcomes for elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2011;124:2397–404. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.025452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manoukian SV, Feit F, Mehran R, et al. Impact of major bleeding on 30-day mortality and clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: an analysis from the ACUITY Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1362–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rao SV, Jollis JG, Harrington RA, et al. Relationship of blood transfusion and clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2004;292:1555–1562. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bendayan M, Bibas L, Levi M, et al. Therapeutic interventions for frail elderly patients: part II. Ongoing and unpublished randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;57:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bibas L, Levi M, Bendayan M, et al. Therapeutic interventions for frail elderly patients: part I. Published randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;57:134–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferrante G, Rao SV, Juni P, et al. Radial versus femoral access for coronary interventions across the entire spectrum of patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:1419–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bromage DI, Jones DA, Rathod KS, et al. Outcome of 1051 octogenarian patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: observational cohort from the London Heart Attack Group. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003027. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.003027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Melloni C, Alexander KP, Chen AY, et al. Unfractionated heparin dosing and risk of major bleeding in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2008;156:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alexander KP, Roe MT, Chen AY, et al. Evolution in cardiovascular care for elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE National Quality Improvement Initiative. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1479–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.