Abstract

Pyrroles are an exciting class of organic compounds with immense medicinal activities. This manuscript presents the structural and quantum mechanical studies of 1-(2-aminophenyl) pyrrole using X-Ray diffraction and various spectroscopic methods like Infra-Red, Raman, Ultra-violet and Fluorescence spectroscopy and its comparison with theoretical simulations. The single-crystal X-ray diffraction values and optimized geometry parameters also were within the agreeable range. A fully relaxed potential energy scan revealed the stability of the possible conformers of this molecule. We present the density functional theory results and assignment of the vibrational modes in the infrared spectrum. The experimental and scaled simulated vibrations matched when density functional theory simulations (B3LYP functional with 6–311++G∗∗). The electronic spectrum was simulated using time-dependent density functional theory with CAM-B3LYP functional in dimethylsulphoxide solvent. The fluorescence spectrum of the compound was studied at different excitation wavelengths in the dimethylsulphoxide solvent. The stability of the molecule by intramolecular electron transfer by hyperconjugation was studied with the natural bond orbital analysis. Frontier molecular orbitals and molecular electrostatic potentials of the compound gave an idea about the reactive behaviour of the compounds. Prediction of activity spectral studies followed by docking analysis indicated that the molecule is active against arylacetonitrilase inhibitor.

Keywords: Organic chemistry, Theoretical chemistry, Pharmaceutical chemistry, 1-(2-Aminophenyl) pyrrole(2APP), XRD, FT-IR, Fluorescence, UV-VIS, DFT

Organic chemistry, Theoretical chemistry, Pharmaceutical chemistry, 1-(2-Aminophenyl) pyrrole(2APP), XRD, FT-IR, Fluorescence, UV-VIS, DFT.

1. Introduction

Pyrrole is one of the most important among aromatic five-membered heterocyclic compounds as it is present in diverse bioactive compounds like porphyrin in heme, chlorines in chlorophyll, and corrin ring in vitamin B12. Phenylpyrrole derivatives are used as precursors of poly-N-phenylpyrroles, a type of conducting polymer used in electrochemical capacitors [1], sensors [2], coating materials used in solid-phase microextraction [3] batteries and different energy storage devices [4]. Computational study of the high energy density pyrrole compounds also was reported [5]. Microwave structural investigation represents that the molecular geometries like bond lengths and angles are similar within a few per cent. So, the pyrrole is very identical to an oblate symmetric top with a meagre degree of asymmetry (k = 0.94). Pyrrole belongs to the C2V point group, which has 24 normal modes of vibration. Its vibrational spectrum was available a long time ago. Lord et al. published Infrared and Raman spectroscopic experimental data and gave complete assignments to 24 normal modes in 1942 [6]. IR spectra of a pyrrole-pyridine complex in CCl4 and its quantum chemical studies were also reported [7]. Raman spectroscopy is an important method to do the structure elucidation of PPy (polypyrrole) in various physical states [8]. The N-heterocyclic benzimidazole compound shows inter/intramolecular hydrogen bonding and charge transfers from the N–H bond of pyrrole ring [9]. Pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid (PCA) is a biologically active compound that behaves as a ligand. The spectroscopic analysis helped to evaluate the amount of effect of metal ions on the electronic charge circulation of pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid [10]. Liu has shown using theoretical studies that, pyrolysis of pyrrole gives hydrogen radical from hydrogen cyanide [11]. Among many experimental techniques of laser spectroscopy, IR spectroscopy is an excellent method to probe intermolecular interactions like H-bonds and Vander Waals interactions. Recently, Y. Matsumoto et al. [12] reported the IR cavity ring-down spectroscopy (IR-CRDS) of the pyrrole (C4H5N) clusters in the NH stretching region. The first infrared spectrum of pyrrole was published in the first decade of the 20thcentury [13]. The work of Lord et al. [6] was the major comprehensive work on vibrational spectroscopy of pyrrole. La Regina reported some pyrrole derivatives which can be used as tubulin polymerization inhibition activity [14].

We present the detailed study of 1-(2-aminophenyl) pyrrole(2APP) in this manuscript. It is used in organic semiconductors [15] and the synthesis of compounds with interesting biological and pharmacological properties [16]. In this connection, we were enthused to examine the spectroscopic properties of the investigated compound. In this manuscript, we describe the detailed structural and spectroscopic properties of 1-(2-aminophenyl) pyrrole(2APP) using experimental methods (XRD, FT-IR, UV-Vis, and Fluorescence spectrum) and theoretical simulations. Different theoretical tools like molecular mechanics, density functional theory etc. are used whenever appropriate. We also aimed to study in detail the various physicochemical properties of this compound with particular reference to its non-linear optical properties and biological activities.

2. Methodology

2.1. Synthesis of single crystals

The starting material of the 1-(2-aminophenyl) pyrrole was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (USA). 20 mg of the compound was dissolved in 20 ml of methanol and warmed to heating in a 25 ml conical flask. After slow evaporation, the needle-shaped crystal formed after two days of which we took single crystal XRD and other spectral measurements are given below.

2.2. Spectral measurements

The Fourier transform Infrared spectrum of the compound 1-(2-aminophenyl) pyrrole was measured in the range 4000 to 400 cm−1 using a GX Fourier transform spectrometer fitted with IR Nicolet microscope and KBr beam splitter by powder method at the resolution ±1 cm−1. FT- Raman spectrum of 2APP was determined using Nicolet Magna 750 Raman spectrometer at the resolution of 4 cm−1in range 4000–400 cm−1 equipped with an InGaAs detector. Neodymium: Yttrium Aluminum Garnet Laser (1064 nm line and typical laser power of 500mW) excitation source. UV-Vis absorption spectra from a Cary 5000 UV-VIS-NIRspectrophotometer and Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer gave further experimental insights.

2.3. XRD-crystallography

Single crystal X-ray diffraction measurements of the compound were carried by taking a block shape crystal with dimension 0.60 × 0.25 × 0.20 mm out on Brukeraxs kappa apex2 CCD diffractometer with Mo Ka radiation (0.71073) at 293 K Table S1 (Supplementary). We performed data reduction with the SAINT program [17], and structure solving with using the SIR92 program [18]. With the help of SHELXL97 program, we refined the structure [19]. Structure-invariant direct methods were used for primary atom site locations, and secondary atom site locations were found from the difference Fourier map. The software used to prepare the material for publication was Mercury 2.3 (Build RC4) and ORTEP-3 [20,21]. The complete set of structural parameters of a molecule in the CIF format is available from the Cambridge Crystallographic Database Centre under no CCDC 1825686. The packing was stabilized by van der Waals interaction shown in supplementary Figure S1.

3. Computational methodology

All theoretical calculations were performed using the Gaussian 09 program package within the framework of density functional methods [22]. The most optimized structural parameters, energy, and vibrational frequencies of 2APP have been calculated in the gas phase using B3 [23] exchange functional combined with LYP [24] correlation functional resulting in the B3LYP density functional method at 6–311++G∗∗ level of theory with no symmetry constraints imposed. Optimized geometries are subjected to vibrational analysis to ensure the global minima on the potential energy surface with no imaginary frequency. The results of the quantum chemical calculations were visualized using Gauss-View [25] and Chemcraft molecular visualization programs [26]. To enhance the coincidence between the calculated and experimental wavenumbers, the theoretical harmonic wavenumbers were scaled down for a better matching. For this purpose, the scaling of the force fields was performed based on the SQMFF procedure [27]. The Cartesian representation of the theoretical force constants has been calculated at the optimized geometry by considering a molecule under C1 point group symmetry. The transformation of the force field from Cartesian to internal local-symmetry coordinates analysis calculation of total energy distribution (TED) with the version V7.0-G77 of the MOLVIB program [28]. The NBO. measurements were performed using the NBO 3.1 program package, as developed in the Gaussian 09W.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Molecular structure

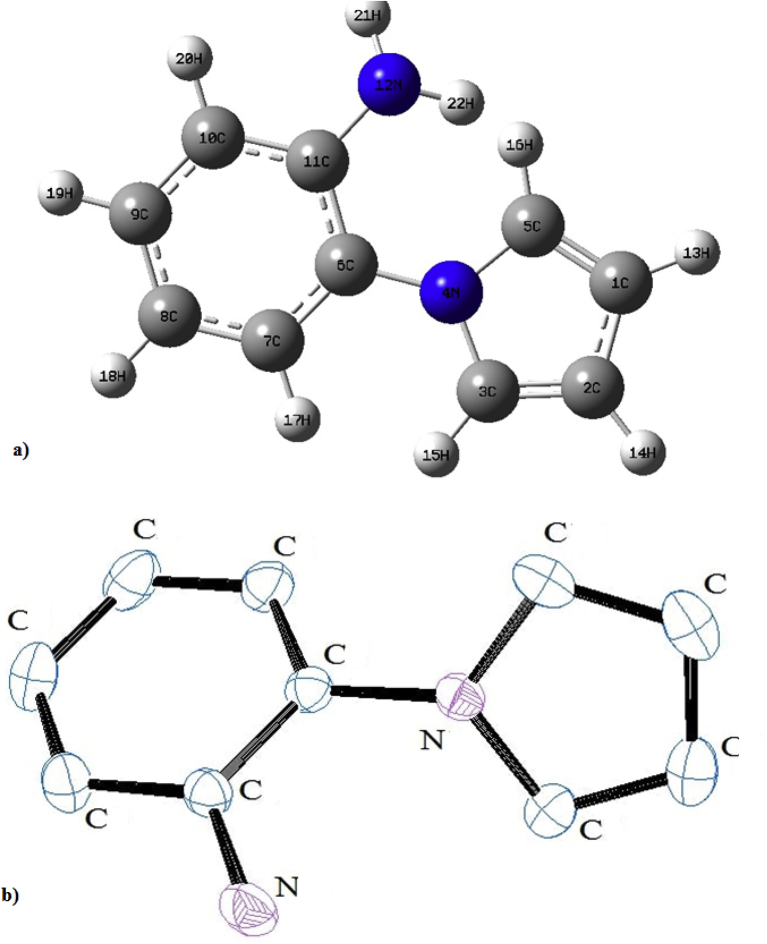

The crystal structure examines of 2APP showed that the material was crystallized in the monoclinic space group with a Z value of 4 with unit cell dimensions a = 19.8514(16) Å, b = 5.7268(4) Å, c = 7.7715(6) Å and α = γ = 90◦, β = 105.812(7)◦ (see Table S1). The structural examination of the compound revealed that the compound was unsymmetrical with the point group Cs. The structural parameters like bond lengths, bond angle, and dihedral angles of the investigated molecule were calculated by the B3LYP method with a 6–311++G∗∗ basis set and compared with the experimentally determined crystallography data. Theoretical values, along with XRD values of the molecular structure, were summarized in Table S2. Optimized geometrical structure of the compound 2APP viewed from the Gauss view Software was shown in Figure 1. The molecular structure of the 2APP, the scheme was drawn at 30% probability displacement ellipsoid, is depicted in (XRD ORTEP diagram) Figure 1. From Table S2, It can be seen that there are some deviations in the computed geometric parameters and from the experimental values. These differences are because the crystalline state involves the intermolecular hydrogen bonding, whereas the results of the calculations apply to the gas phase. The experimentally measured XRD data of a substituent phenyl ring, we noticed that all the C–C bond lengths were found to be small deviations approximately 1.37 Å in B3LYP. In the case of the pyrrole ring, the C–C bond lengths were 1.40 Å for C1–C2, 1.35 Å for C2–C3, C1–C5. Further, N–C bond lengths were 1.38 Å for both N4–C3 and N4–C5. After that, it was observed that the maximum deviation in the bond lengths when compared to experimental data was 0.157Å for N12–H22. The order of the observed bond angles follows the trend C1–C5–H16 > C2–C3–H15 > C1–C2–H14 > C1–C2–H13, which shows a small deviation with the theoretical values. The maximum variation in the torsional angle for C7–C6–N4–C3 was 9.14°, which shows a significant difference due to the attachment of pyrrole and substituted benzene ring.

Figure 1.

a) Optimised geometry of 1-(2-aminophenyl) pyrrole along with numbering of atoms b) ORTEP diagram with basic skeleton.

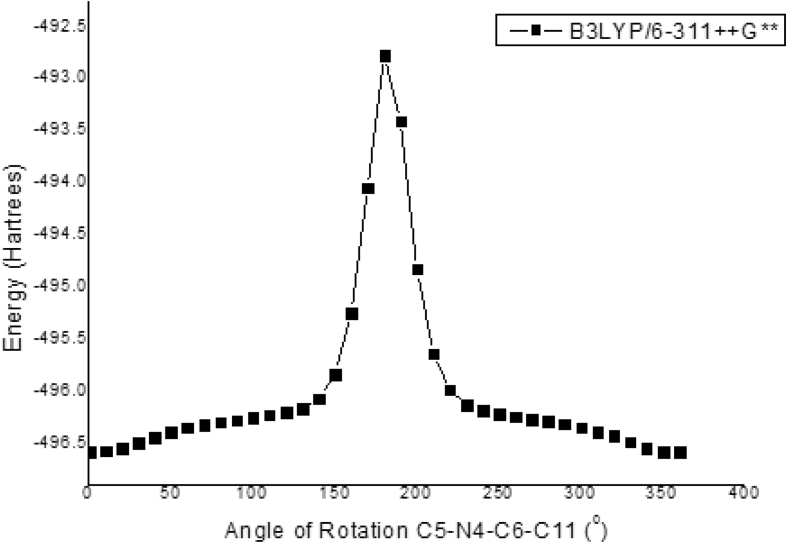

4.2. PES scan study

Molecules can form infinite number of conformers as a result of free rotation about single bonds. The most stable conformer can be determined by conducting a relaxed potential energy scan using the B3LYP/6–311++G∗∗ level of theory. The relation between the potential energy and molecular geometry can be expressed as the potential energy surface (PES) diagram, which will help to ascertain the possible conformations of the 2APP and its relative stability. From the XRD data, the torsional angle of H22–N12–C11–C6 was -1.00°, and in the simulated optimized geometry, it was -0.7580° for the B3LYP. It indicates an unexpected bent conformation of the molecule, in contrary to the expected pyramidal structure. The scan was performed at a scan-interval of 10° in 36 steps from the dihedral of 0–360°. The potential energy surface scan for the selected torsional angle H22–N12–C11–C6 was shown in Figure 2. The H22–N12–C11–C6 torsional angle was increased by 10° from 0° to 360°, where other geometrical parameters have been concurrently relaxed. According to the figure, the global minimum energy was observed at 0° with an energy value of -496.70564 Hartrees, which shows the least energy (stable conformation) of 2APP and the global maximum was at 200o.

Figure 2.

Relaxed potential energy surface scan for dihedral angle H22–N12–C11–C6 of 1-(2-aminophenyl)pyrrole.

4.3. Vibrational analysis

Based on the calculations, 1-(2-Aminophenyl) pyrrole has a planar structure of Cs point group symmetry. 2APP contains 22 atoms and hence 60 normal modes of vibrations which can be distributed among the symmetry species as Γ3N−6 = 41A′ (in-plane) + 19A″ (out-of-plane) [29].

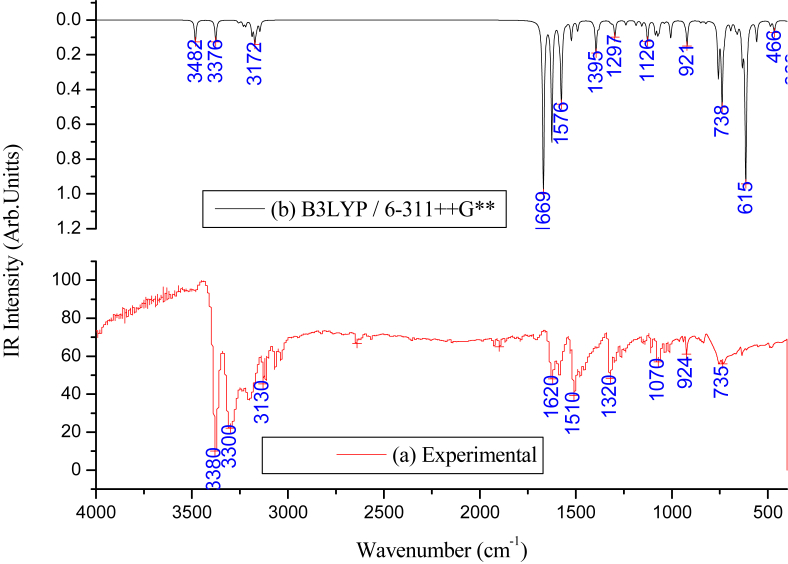

All the vibrational modes are identified in the recorded FT-IR spectrum. The investigated compound has been tested to be Raman in-active vibrations. We compared the experimentally recorded FT-IR spectra and the theoretically simulated spectra (Figure 3). The internal coordinates of the compound have been presented in Table S3 (Supplementary). Further, the local symmetry coordinates, which are non-redundant, were represented in Table S4 (Supplementary). The calculated frequencies by the B3LYP/6–311++G∗∗ basis set were scaled using available scaling factors and compared with the experimentally recorded frequencies [30]. The scaled and un-scaled frequencies, along with PED (potential energy distribution), are presented in Table 1.

Figure 3.

(a) Experimental, (b) Simulated FT-IR spectra of 1-(2-aminophenyl)pyrrole.

Table 1.

Detailed assignments of fundamental vibrations of 1-(2-Amiνopheνyl) pyrrole by normal mode analysis based on SQM force field calculations usingB3LYP/6–311++G∗∗.

| Νo. | Experimental (cm−1) FT-IR | Scaled Frequencies (cm−1) | Un-scaled frequencies(cm−1) | Intensity IIRb | Characterization of normal modes with PED (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3380νs | 3482 | 3675 | 13.50 | υΝHAS (99) |

| 2 | 3310νs | 3376 | 3562 | 13.38 | υΝHSS (99) |

| 3 | 3258 | 3286 | 1.23 | υCH (99) | |

| 4 | 3252 | 3280 | 0.73 | υCH (99) | |

| 5 | 3232 | 3260 | 3.19 | υCH (98) | |

| 6 | 3205s | 3220 | 3247 | 3.29 | υCH (99) |

| 7 | 3187 | 3214 | 8.40 | υCH (99) | |

| 8 | 3130νs | 3172 | 3199 | 13.22 | υCH (99) |

| 9 | 3164 | 3191 | 3.42 | υCH (98) | |

| 10 | 3113w | 3146 | 3173 | 6.60 | υCH (97) |

| 11 | 1620s | 1669 | 1674 | 100 | υCCAR(28), υCΝR2 (22), βΝH2SC (19), βCH (12), |

| 12 | 1625 | 1649 | 67.36 | υCCAR(32), υCΝSUB (19), βCH (14), βR2SYM (12) | |

| 13 | 1580νw | 1586 | 1636 | 9.97 | υCCAR(39), βΝH2SC (28), βΝH2TW (10) |

| 14 | 1510s | 1576 | 1579 | 61.45 | υCCAR(27), βCH (25), βΝH2SC (20), υCΝSUB (10) |

| 15 | 1549 | 1554 | 0.47 | υCCAR(63), βCH (31) | |

| 16 | 1538νw | 1523 | 1523 | 11.14 | βΝH2SC(36), υCCAR (21), βCH (13) |

| 17 | 1491 | 1504 | 7.45 | βΝH2RO (53), υCCAR (26), | |

| 18 | 1408 | 1442 | 0.25 | υCCAR (61), βCH (21), υCΝSUB (10) | |

| 19 | 1395 | 1367 | 19.30 | υCCAR(37), βCH (33), βR1SYM (15) | |

| 20 | 1381 | 1360 | 3.66 | βCH (36), υCΝR2 (23), βR2TRI (13), υCCAR (11) | |

| 21 | 1320w | 1321 | 1358 | 4.60 | υCCAR (39), βCH (32), βΝH2RO (11) |

| 22 | 1313 | 1335 | 3.00 | βCH(59), υCCAR (20), υCΝR1 (14) | |

| 23 | 1297 | 1298 | 5.59 | υCCAR (58), βCH(23) | |

| 24 | 1239 | 1275 | 2.72 | υCΝR1 (60), βCH (16), υCCAR (10) | |

| 25 | 1187 | 1188 | 2.68 | βCH (74), υCCAR (25) | |

| 26 | 1153s | 1157 | 1169 | 3.53 | βCH (44), υCCAR (35), βΝH2RO (12) |

| 27 | 1141s | 1127 | 1140 | 8.20 | βCH (41), υCCAR (39) |

| 28 | 1086 | 1101 | 9.09 | βCH (56), υCCAR (24), υCΝR1 (10) | |

| 29 | 1075νs | 1074 | 1096 | 8.78 | υCΝR1 (43), υCCAR (26), βCH (20) |

| 30 | 1066 | 1084 | 7.37 | βCH (40), υCCAR (40) | |

| 31 | 1036s | 1039 | 1062 | 1.13 | βΝCSUB (27), βCH (21), υCCAR (17), υCΝR1 (17), βR1SYM (15) |

| 32 | 1013νs | 1006 | 1036 | 8.46 | βCΝSUB (27), βCH (21), υCCAR (17), υCΝR1 (17), βR1SYM (15) |

| 33 | 963 | 969 | 0.02 | ωCH (79), τR2TRI (13) | |

| 34 | 932 | 940 | 1.17 | ωCH (90) | |

| 35 | 924w | 921 | 939 | 13.18 | βCH (42), βR2SYM (36) |

| 36 | 873 | 884 | 0.08 | βR1SYM (58), βR1ASY (29) | |

| 37 | 869 | 874 | 0.08 | ωCH (85), τR1SYM (10) | |

| 38 | 850 | 859 | 1.00 | ωCH (65), τR2TRI (12) | |

| 39 | 833m | 837 | 842 | 0.57 | βR2TRI (34), βCH (31), υCCAR (13) |

| 40 | 823m | 823 | 827 | 1.56 | ωCH(83), |

| 41 | 756w | 758 | 764 | 28.22 | ωCH(92) |

| 42 | 735νw | 738 | 743 | 45.54 | ωCH(84) |

| 43 | 727 | 739 | 4.59 | τR2TRI (54), ωCΝR2 (15), τR2ASY (12), ωCΝSUB (10), | |

| 44 | 693 | 698 | 4.81 | ωCH (92) | |

| 45 | 668 | 682 | 8.03 | βR1ASY (28), βR2TRI (24), βCH (19), βR1SYM (18), | |

| 46 | 659 | 646 | 4.54 | τR1ASY (33), βR2SYM (15), τR1SYM (14), βCH (14), ωΝCSUB (10) | |

| 47 | 633 | 625 | 3.75 | τR1SYM (50), τR1ASY (24), ωCH (14) | |

| 48 | 635m | 615 | 595 | 86.55 | βΝH2WA (45), τR2TRI (10), τR1SYM (10) |

| 49 | 558 | 566 | 0.21 | τR2SYM (25), τR2ASY (14), ωCΝR2 (12), ωCΝSUB (12), τR2TRI (10), ωCH (10) | |

| 50 | 555 | 562 | 51.29 | βR2ASY (53), βR2SYM (27) | |

| 51 | 489m | 486 | 500 | 0.78 | βΝCR2 (21), τR2ASY (15), ωCΝR2 (13) |

| 52 | 467νw | 466 | 472 | 12.53 | ωCΝR2 (33), τR2ASY (14), ωCΝSUB (12), βΝCR2 (11), τR2SYM (10) |

| 53 | 370 | 371 | 20.91 | τΝH2TW (60) | |

| 54 | 351 | 352 | 4.73 | τΝH2TW (18), βR2ASY (15), βR2SYM (14), βCH (13), βΝCSUB (11) | |

| 55 | 327 | 335 | 5.65 | τR2ASY (44), ωCH (13), βCΝSUB (13), τΝH2WA (11) | |

| 56 | 298 | 300 | 0.28 | βR2SYM (34), βΝCR2 (21), βCH (13), βΝCSUB (10) | |

| 57 | 209 | 212 | 1.14 | τR2SYM (49), τR2TRI (15), ωCΝSUB (10) | |

| 58 | 117 | 119 | 0.06 | ωΝCSUB (27), βCΝSUB (25), βΝCSUB (16), τR2SYM (11) | |

| 59 | 93 | 91 | 0.15 | ωCΝSUB (50), ωΝCSUB (25), βCΝSUB (12) | |

| 60 | 60 | 60 | 0.04 | τCΝCC (72), βR2SYM (10) |

a Abbreviations: υ, stretching; β, iν plane bending; ω, out of plane bending; τ, torsion, ss, symmetrical stretching, as, asymmetrical stretching, sc, scissoring, wa, wagging, twi, twisting, ro, rocking,ipb, in-plane bending, opb, out-of -plane bending; tri, trigonal deformation, sym, symmetrical deformation, asy, asymmetric deformation, butter, butterfly, ar, aromatic, sub, substitution, vs, νery strong; s, strong; ms, medium strong; w, weak; vw, very weak.

Relative IR absorptionintensities normalized with highest peak absorption equal to 100.

Only PED contributions ≥10% are listed.

4.3.1. C–H vibrations

We observed aromatic C–H stretching frequencies in the region 3000-3100 cm−1, which can be used for quick identification of C–H stretching wavenumbers [31]. If there is any substituent in any position of the compound, they cannot influence the C–H vibrations. Most of the cases, the aromatic compounds have four vibrational wavenumbers in the region 3010-3080 cm−1. Now coming to the present work, the bands scaled at 3258cm−1, 3252cm−1, 3232cm−1, 3220cm−1, 3187 cm−1 were assigned to CH stretching with mode numbers from 1 to 8. These values show a good agreement with the observed values at 3114cm−1, and 3130 cm−1 and corresponding PED was shown in Table 1. Further, the C–H in-plane bending vibrations appeared in the range of 1000–1550 cm−1, and C–H out of plane bending vibrations appear in the range 700–1000 cm−1. In the present work, the vibrations scaled at 1381cm−1, 1313cm−1, 1187cm−1, 1157cm−1, 1127cm−1,1086cm−1, 1066cm−1 and 921 cm−1 were assigned to CH in-plane bending vibrations. The corresponding modes are observed at 1153cm−1 and 1141cm−1, show a good agreement. Similarly, the vibrations scaled at 963cm−1, 932cm−1, 869cm−1, 850cm−1, 823cm−1,758cm−1, 738cm−1 and 693 cm−1 were assigned to CH out of plane vibrational modes as depicted in the table whose correspondence may be found at 823cm−1, 756 cm−1, 735cm−1in the FTIR spectrum.

4.3.2. C–C ring vibrations

The C–C stretching vibrations normally occur in the region 1650-1350 cm−1, which are not much influenced by substitution in the ring [32]. In the present work, the C–C stretching vibrations scaled at 1669cm−1, 1625cm−1, 1586cm−1, 1576cm−1, 1549cm−1, 1408cm−1, 1395cm−1, 1321cm−1, 1297 cm−1 were assigned to C–C stretching modes. The modes observed at 1620cm−1, 1510cm−1and 1320 cm−1 in the FTIR spectrum shows a good relevance with the calculated data. The modes scaled at 873 cm−1and 668 cm−1 were assigned to C–C–C in-plane bending vibrations, and the modes scaled at 659cm−1and 633 cm−1 were assigned to C–C–C out of plane bending vibrations which are not observed in the FT-IR spectrum. The bands scaled at 837cm−1, 555cm−1, and 298 cm−1 were assigned to C–C–C in-plane bending vibrations, and the bands scaled at 729cm−1, 657cm−1 and 639 cm−1 were assigned to C–C–C out of plane bending vibrations in the benzene ring.

4.3.3. NH2 group vibrations

NH2 group shows two stretching frequencies, i.e., asymmetric and symmetric stretching frequencies. Further, the asymmetric stretching frequency will be higher than the symmetric stretching frequency [33]. In the present work, the investigated compound has one NH2 group, and hence it contains one asymmetric and one symmetric stretching wavenumbers. The scaled frequencies at 3482 cm−1and 3376 cm−1were assigned to NH2 asymmetric and symmetric modes, respectively. The influential bands observed at 3380cm−1and 3310 cm−1 show a good agreement with the calculated values as it can be noticed from Table 1. Furthermore, the NH2 group has scissoring (NH2), rocking (NH2), wagging (NH2) and torsion (NH2) modes. The internal deformation vibrations known as NH2 scissoring frequency obtained at 1523cm−1 is ideal within the range (1500–1650cm−1) reported for aniline by Jesson and Thompson [33], and this observation conforms with the experimental value of 1538 cm−1 in FT-IR spectrum. The –NH2 wagging mode has been identified with the frequency at 635 cm−1 in FTIR, and this is in ideal coincidence with the reported region of 600–909 cm−1. The theoretical scaled value at 615cm−1 by B3LYP/6–311++G∗∗ shows ideal agreement with experimental data. The rocking mode at 1491 cm−1 has not been observed experimentally, so we predicted theoretically. The torsional mode has been assigned at 351cm−1.

4.3.4. C–N vibrations

Generally, the C–N stretching frequencies are observed in the region 1300 - 1100 cm−1. The identification of C–N stretching bands is complicated since this region contains a mixture of bands. However, in the present work, the scaled values at 1239cm−1and 1074 cm−1 were assigned to C–N stretching, which shows a good agreement with the observed value at 1075 cm−1in the FT-IR spectrum. These assignments find support from the work of Lord et al. in the case of related molecules [6].

4.4. NBO. Analysis

The natural bond orbital (NBO) studies give practical information about the intra and inter-molecular interaction, charge transfer of the molecule. The most crucial successful interaction with their second-order perturbation energies E (2)is presented in Table S5, which gives valuable information about the calculation of delocalization and hyperconjugation. The second-order Fock matrix analysis was performed to 2APP under investigation to know the different types of donor and acceptor interactions and energies in the molecule based on NBO analysis. The donor NBO. (i) and acceptor NBO. (j) and the stabilization energy E (2) can be represented as

| (1) |

Here, or F2ij is the Fock matrix element i and j NBO orbitals, εσ∗ and εσ are the energies of σ, and σ∗ Natural bond orbitals and nσ is the population of the donor σ orbital. More substantial is the E(2) value; the high intensive is the interaction between electron donors and electron acceptors, i.e., the more donating tendency from electron donors to electron acceptors and the higher the extent of conjugation of the entire system. The NBO calculations have been performed on 2APP by using NBO 3.1 program as developed in the Gaussian 09W package at B3LYP/6–311++G∗∗ level of theory to determine the intermolecular interaction, hyperconjugation and the delocalization of electron density. The most critical interactions in the heterocyclic pyrrole molecule with lone pair N4 with that of antibonding C1–C5 and C2–C3, stabilization energy of 33.24 and 33.69 kJ/mol respectively which denotes large delocalization. The maximum energy occurs from π ∗ of C6–C11 to π of C7–C8 (311.39 kJ/mol), as listed in Table S5 (Supplementary).

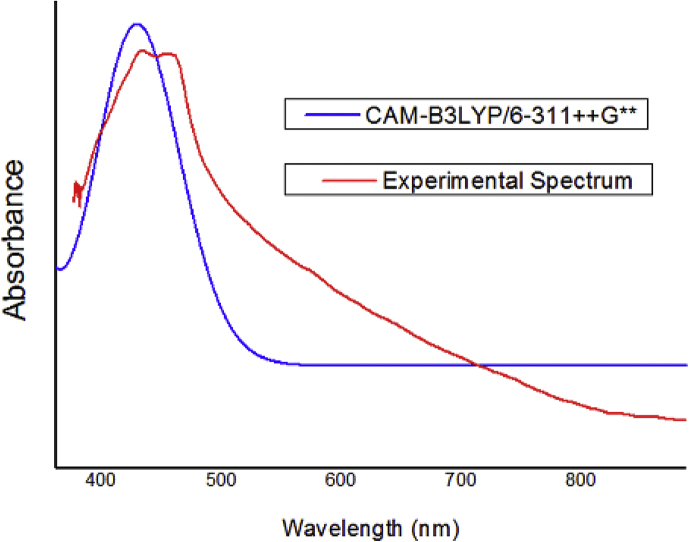

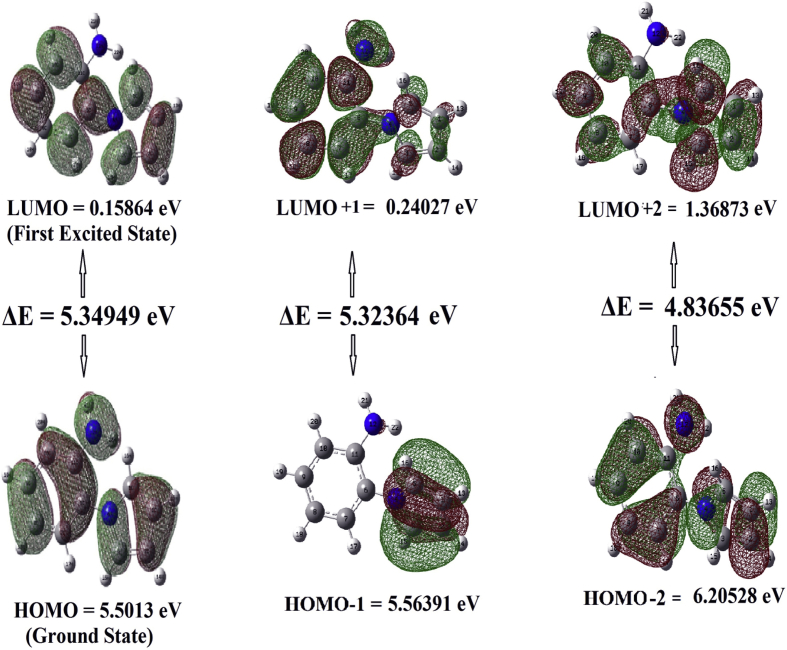

4.5. UV-vis & fluorescence spectra and frontier molecular orbital analysis

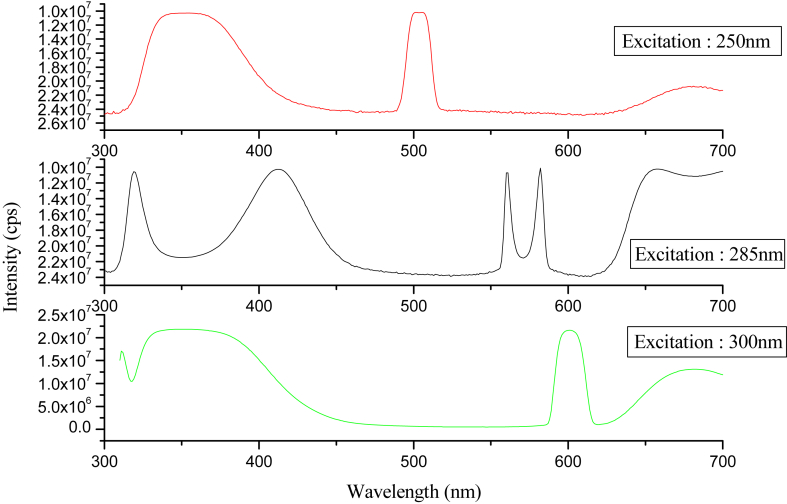

The UV-visible absorption of the compound is recorded in DMSO at the concentration of 1 × 10−5 M under ambient conditions. The computed and experimental UV-Visible spectrum of 2APP was shown in Figure 4. Theoretically, the maximum absorptionλmax was calculated by using the TD-DFT/CAMB3LYP method with a 6–311++G∗∗ basis set to get more accurate values. Generally, λmax is resulting from the electronic transition from HOMO to LUMO. However, in the present study, the computed λmax of the investigated compound in the gas phase was 446 nm. Its counterpart, i.e., the experimental λmax of the compound in DMSO was found to be 461 nm, which shows a moderate agreement with the theoretical spectrum. Another peak was computed at 435 nm, whose counterpart was observed at 440 nm. The calculated visible absorption maxima, λmax along their experimental wavelengths with a significant contribution of HOMO, LUMO, and oscillator strength (ƒ) of the compound have been listed in Table 2. We recorded the fluorescence emission spectrum of 2APP (1 10−5 M) in DMSO at three exciting wavelengths 250, 285, and 300 nm, and they were presented in Figure 6. Further, we addressed the question of whether fluorescence spectroscopy can be used to identify differences in the stability and conformation of the compound under study. The emission spectra were measured at excitation wavelengths at 250 nm, 285 nm 300 nm, and a slit width of 5 nm. Upon excitation at 250 nm, 285nm, and 300 nm, we observed a strong emission band at 350 nm, 380 nm, and 400 nm. These are corresponding to the origin of the S1S0 electronic transition. An evaluation of the normalized emission spectra at 250 and 300 nm excitation indicates that there are no differences in the line shape; however, at 285 nm excitation, there are differences in the line shape of the spectra. It can be noticed that the excitation maxima follows redshift, which indicates that the compound is a beneficial source of interaction with visible light (see Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Comparison of theoretical and experimental UV-Vis spectra of 1-(2-aminophenyl) pyrrole in DMSO.

Table 2.

The UV–Vis excitation energy and oscillator strength for 1-(2-aminophenyl)pyrrole calculated by TD-DFT/B3LYP/6–311++G∗∗Method.

| Experimental |

TD-DFT/CAM-B3LYP/6–311++G∗∗ |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO solvent | ||||||

| Wavelength (nm) | Energy (eV) | Abs. | Wavelength (nm) | Energy (eV) | ƒ | Major contribs |

| 461 | 4.5341 | 0.4245 | 446 | 4.6865 | 0.1119 | HOMO- > LUMO (81%) |

| -- | 4.6244 | -- | 441 | 4.8733 | 0.0053 | H-1- > LUMO (95%) |

| -- | 5.1340 | -- | 431 | 5.2075 | 0.004 | H-1- > L+1 (84%), HOMO- > L+1 (10%) |

| 440 | 5.1683 | 0.1128 | 435 | 5.2335 | 0.1126 | H-2- > LUMO (32%), H-1- > L+1 (11%), HOMO- > L+1 (41%) |

Figure 6.

Different electronic transitions between the frontier orbitals.

Figure 5.

Fluorescence spectra of 1-(2-aminophenyl) pyrrole in different excitation wavelengths.

The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) are the orbitals which denote the chemical stability of the molecule. The HOMO, which indicates the ability to donate an electron and LUMO, shows the ability to accept an electron [34]. Molecular orbitals (HOMO and LUMO) give useful information for physicists and chemists. They also give information about the most reactive position in the π-electron molecule and explain several types of reactions in the conjugated systems [35]. Figure 6 represents the HOMO and LUMO orbitals of the compound. The different molecular orbitals [MO: 37–MO: 48] of 2APP, under Cs symmetry, were shown in Supplementary Figure S2. This figure depicts various MOs and their deeds at different levels. Positive and negative charges are equally distributed in both HOMO and LUMO levels. Also, a more negative charge is distributed around the benzene ring in MO-46. It can be noticed from the figure that a minimal amount of charge is distributed on the benzene ring in MOs 41, 47, and 48. Quantum chemical descriptors were used to study the biological activity of the quantitative structure-activity relationship for the molecule. The HOMO-LUMO energy gap, Ionization potential (I), Electron affinity (A), chemical potential (μ), Electrofilicity index (ω), Global Softness (σ), Total energy change (ΔET), and Dipole moment(D) of 2APP have been calculated using DFT/B3LYP-6-311++G∗∗ basis set. The results were summarized in Table 3. Nowadays, the HOMO – LUMO energy gap between has been used to prove the bioactivity from intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) [36, 37]. Due to the low value of the HOMO-LUMO energy gap, these compounds have a high softness nature. The low value of the electrophilicity index around -1.0593 eV, suggests the biological activity of the compounds, as that can easily bound with the target proteins or enzymes, which is evident from docking studies.

Table 3.

The calculated quantum chemical parameters for 1-(2-aminophenyl)pyrroleobtained by B3LYP/6–311++G∗∗ calculations.

| Property | B3LYP/6–311++G∗∗ |

|---|---|

| Total energy (eV) | -13512.95 |

| EHOMO(eV) | -5.50817 |

| ELUMO(eV) | -0.15864 |

| EHOMO-ELUMO(eV) | 5.34953 |

| Ionization potential(I) (eV) | -5.50817 |

| Electron Affinity(A) (eV) | -0.15864 |

| Chemical potential (μ) (eV) | -2.833405 |

| Electronegativity (χ)eV | 2.833405 |

| Chemical hardness(η)eV | -2.674765 |

| Electrofilicity index (ω) eV | -1.059309 |

| Global Softness (σ)eV | -0.373864 |

| Total energy change(ΔET) eV | 0.668691 |

| Dipole moment(D) | 1.9413 |

4.6. Nonlinear optical (NLO) properties

NLO properties of any compound give valid information, i.e., they provide properties of optical modulation, optical switching, optical logic, and optical memory for the prominent technologies in the region of telecommunications, signal processing, and interconnections [38]. To know NLO properties of the compound, by DFT/B3LYP method to the investigated molecule, the dipole moment (μ), the mean first hyperpolarizability (β), the mean polarizability (α0), the anisotropy of the polarizability (Δα) using x,y,z elements can be calculated by using Gaussian 09W in finite-field approach is presented in Table 4 and equated as follows [39, 40].

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Table 4.

Calculated all β components and β tot value of1-(2-aminophenyl)pyrrolebyB3LYP/6–311++G∗∗method.

| μ and components | B3LYP/6–311++G∗∗ | components | B3LYP/6–311++G∗∗ |

|---|---|---|---|

| x | 0.5240832 | βxxx | 111.4655101 |

| y | 0.5202414 | βxxy | -17.9044683 |

| z | 0.1525503 | βxyy | 80.022578 |

| (D) | 0.56858590 | βyyy | -33.3158682 |

| xx | 153.2053703 | βxxz | 20.6075202 |

| xy | -2.2506453 | βxyz | -55.9881151 |

| yy | 79.34518 | βyyz | 40.5048559 |

| xz | 1.8711959 | βxzz | 9.5072421 |

| yz | -24.7250373 | βyzz | -35.3795389 |

| zz | 86.1419551 | βzzz | 29.694309 |

| Δα | 40.82122 × 10−12esu | ||

| (esu) | 15.74341 × 10−12esu | βtotal (esu) | 1.730348×10−30esu |

and

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

The above values, i.e., mean polarizability and mean first-order hyperpolarizability values of the Gaussian 09 output, are showed in atomic units (a.u). Therefore, the measured values have been converted into electrostatic units (esu) (α: 1a.u = 0.1482 × 10−12esu, β: 1 a. u = 8.6393×10−33esu) [41]. Urea is an ideal compound used for understanding the NLO properties of the investigated molecules. Therefore, the NLO properties of urea are utilized for comparative purposes. The values of the mean polarizability (α0) and the mean first hyperpolarizability (β) of the investigated molecule were 15.74341 × 10−12esu and 1.730348×10−30esu. These values are approximately 4 and 9 times, respectively, greater than the values of urea. The dipole moment of the compound is 0.5685 Debye, which indicates the non-uniform distribution of atomic charges. Thus it could be a potential molecule for future studies of non-linear optical properties.

4.7. Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP)

MEP investigation gives information about the electrophilic and nucleophilic sites in a reaction and also shows that the hydrogen bonding interactions [42]. The molecular electrostatic potential V(r) is mainly related to the electron density in a molecule. To know the MEP values in a molecule, the following expression is used to calculate the MEP values [43].

| (9) |

Here, N represents the total number of nuclei; ZA represents the charge of the nucleus placed at RA, ρ (r′) represents electron density function of the molecule, and r′ is the dummy integration variable. Further to know the positive, negative, and neutral electrostatic potential areas of the molecule understudied, MEP was calculated by using B3LYP/6–311++G∗∗ level of theory. The MEP mapping of the investigated compound represented in Supplementary Figure S3. From the figure, it can be seen that the nitrogen labelled N12 is surrounded by red colour (negative) and two hydrogens atoms H21 and H22 represents a nucleophilic portion of the molecule. The blue colour is located over the benzene ring, which indicates the positive portion, i.e., electrophilic area of the molecule.

4.8. Mulliken atomic charge analysis

Mulliken atomic charge analysis is very important because atomic charges influence polarizability, dipole moment, geometric structure, and much more properties of the compound under investigation [44]. In the present work, the Mulliken atomic charge analysis was carried out to the compound understudied by using the B3LYP method with a 6–311++G∗∗ basis set. The calculated atomic charges are tabulated in Supplementary Table S6 and Fig. S4. From table S6, it was observed that the atoms C1, C2, N4, C7, C8, C9, C10, and N12 have negative charges with the corresponding values 0.142, 0.140, 0.559, 0.121, 0.103, 0.082, 0.130 and 0.668 respectively. The remaining atoms were positively charged. The molecular structure, along with their charges, was represented in Table S6(Supplementary).

4.9. Molecular docking studies

The pyrrole derivatives are usually medicinally active. Prediction of the structure-activity spectra called PASS analysis was to predict the potential medicinal activity using an online tool [45]. The results of the analysis were shown in Table S7 and Fig. S5 of the supplementary information, which indicated that the compound shows a high association towards the activity as arylacetonitrilase inhibitor. We downloaded the protein responsible for this action from the protein data bank with id PDB ID: 3hkx [46]. The ligand, our pyrrole derivative, was docking with the above macromolecule using the Patchdock docking server [47, 48, 49, 50]. The score of the molecular docking between pyrrole derived compound, and the protein (PDB ID: 3hkx) was 2660, full fitness energy is -1263.77 kcal/mol, estimated ΔG (docking score) is -6.18 kcal/mol, and total molecular solvent accessibility is 2695.32 (Ǻ)2. The docking studies help to evaluate the interaction pattern of the ligand with the studied proteins [51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56]. The following passage gives an idea about the various interactions between the guest and the host.

There are several interactions between protein (PDB ID: 3hkx) and pyrrole derived compounds. The pi-alky interactions between pyrrole ring and alanine (A:25) and leucine (A:21) are observed within the bond distance 4.71 and 5.31 Ǻ and pi-pi T shaped interactions between histidine (A:8) and pyrrole ring and amino benzyl at 5.25 and 4.96 Ǻ respectively. A bond between arginine (A:28) and the pyrrole ring contains a pi-cation bond with 3.53 Ǻ is the distance length. Aminobenzyl nitrogen with arginine (A:28) shows positive-positive interactions with 4.84 Ǻ bond length. The unfavourable repulsive interaction between pyrrole nitrogen and amine hydrogens are observed when the bond distance is 1.29 and 1.18 Ǻ. The conventional hydrogen bond interactions between histidine (A:8) and pyrrole and amino benzyl takes place within 3.05 and 3.37 Ǻ (Fig S5). Water-resistance residues (Hydrophobic interactions) of a referred protein and the prepared compound is methionine (A:6), leucine (A:21), alanine (A:25), leucine (A:231) and histidine (A:8) with secondary structure sheet, helix, helix, sheet, and a coil having an average isotropic displacement 18.742, 21.585, 19.736, 20.575 and 25.661 (Ǻ)2 contains positive hydrophobic values are 1.9, 3.8, 1.8, 3.8 and -3.2 respectively.

Water polar interactions (Hydrophilicity interactions) of pyrrole derived compound with protein residues are glutamine (A:7), histidine (A:8), aspartic acid (A:20), leucine (A:21), aspartic acid (A:24) and alanine (A:25) with hydrophobicity values -3.5, -3.2, -3.5, 3.8, -3.5 and 1.8 having average isotropic displacement 18.3, 25.661, 28.973, 21.585, 28.617 and 19.736 (Ǻ)2 through secondary structures sheet, coil, helix, helix, helix, and helix respectively. Neutral interactions between pyrrole and protein residues leucine (A:21), alanine (A:25), proline (A:229) and glycine (A:230) having average isotropic displacement 21.585, 19.736, 26.973 and 22.885 with 27.419, 12.531, 74.191 and 22.762 are residue solvent accessibility (RSA), 23.649, 7.548, 47.299 and 13.586 are side-chain solvent accessibility (SSA), 18.075, 12.516, 58.323 and 31.778 are per cent solvent accessibility (PSA) and 23.797, 82.706, 50.47 and 56.545 per cent side-chain solvent accessibility (PSSA) in the unit (Ǻ)2 respectively. The acidic group interactions between pyrrole derived compound and protein residues are aspartic acid (A:20), leucine (A:21), aspartic acid (A:24) and alanine (A:25) with 123691, 27.419, 83209 and 12.531 are residue solvent accessibility (RSA), 105.166, 23.649, 78.305 and 7.548 is side-chain solvent accessibility (SSA), 84.799, 18.075, 57.046 and 12.516 are per cent solvent accessibility (PSA), 111.077, 23.797, 82.706 and 16.393 are per cent side-chain solvent accessibility (PSSA), and average isotropic displacements are 28.973, 21.585, 28.617 and 19.736 in the units of (Ǻ)2 respectively [57, 58].

The compound's fundamental group interactions, average isotropic displacements in (Ǻ)2 are 25.661, 21.585, 19.736 and 31.38 with protein residue. The compound has 50.129, 23.797, 16.393 and 74.557 per cent side-chain solvent accessibility (PSSA), 40.129, 18.075, 12.516 and 62.452 per cent solvent accessibility (PSA), 62.225, 23.649, 7.548 and 141.547 side-chain solvent accessibility (SSA) and 70.252, 27.419, 12.531 and 143.256 (Ǻ)2residue solvent accessibility (RSA) with the protein residues histidine (A:8), leucine (A:21), alanine (A:25) and arginine (A:28) respectively.

5. Conclusions

The pyrrole derivative 1-(2-aminophenyl) pyrrole was optimised for the stable geometry and compared with the molecular/atomic parameters from the XRD data. The structural data were found in agreement within the acceptable limits. The experimental FT-IR, UV-Visible and Fluorescence spectra were recorded and compared with the scaled simulated IR spectra and UV spectra using TD-DFT and are also found to be in close agreement. The detailed, potential energy distribution of the IR vibrations and assignment of the electronic transitions were also presented. The absorption wavelengths were observed at 461 and 435 nm in the UV-Visible spectrum. Fluorescence spectrum of the compound at different exciting wavelengths shows the redshift for the emission maxima in the compound that represents a good source for the visible spectrum. NBO studies indicated that the molecule is intrinsically stable from hyper conjugative interactions. The most important interactions were the one between lone pair of N4 and antibonding C2–C3, whose stabilization energy was 33.69 kJ/mol indicating large delocalization. NLO. prediction with hyperpolarizability (β) indicates that the molecule posses activity more than urea. Quantum mechanical studies of the frontier molecular orbitals and other various energy descriptors were also presented in the manuscript. MESP reports reactive sites the compound towards electrophilic and nucleophilic agents. Docking studies shows that the molecule is a potential bioactive compound with therapeutic activity. Thus it can be concluded that the presented molecule is having immense physical and biological applications.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Katta Eswar Srikanth: Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

A Veeraiah: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

T. Pooventhiran: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Renjith Thomas: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

K. Anand Solomon: Performed the experiments.

Ch. J. Soma Raju, J Naveenalavanya Latha: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding statement

A.Veeraiah and Katta Eswar Srikanth were supported by SERB, Government of India (Project codeSB/EMEQ/2014).

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Contributor Information

A. Veeraiah, Email: avru@rediffmail.com.

Renjith Thomas, Email: renjith@sbcollege.ac.in.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Sarac A.S., Sezgin S., Ates M., Turhan C.M. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and morphological analyses of pyrrole, phenylpyrrole and methoxyphenylpyrrole on carbon fiber microelectrodes. Surf. Coating. Technol. 2008;202(16):3997–4005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh M., Kathuroju P.K., Jampana N. Polypyrrole based amperometric glucose biosensors. Sensor. Actuator. B Chem. 2009;143(1):430–443. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu J., Pawliszyn J. Solid-phase microextraction based on polypyrrole films with different counter ions. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2004;520(1–2):257–264. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Priya Y.S., Rao K.R., Chalapathi P.V., Veeraiah A., Srikanth K.E., Mary Y.S., Thomas R. Intricate spectroscopic profiling, light harvesting studies and other quantum mechanical properties of 3-phenyl-5-isooxazolone using experimental and computational strategies. J. Mol. Struct. 2020;1203:127461. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li B.T., Li L.L., Li X. Computational study about the derivatives of pyrrole as high-energy-density compounds. Mol. Simulat. 2019;45(17):1459–1464. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lord R.C., Jr., Miller F.A. The vibrational spectra of pyrrole and some of its deuterium derivatives. J. Chem. Phys. 1942;10(6):328–341. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Futami Y., Ozaki Y., Hamada Y., Wojcik M.J., Ozaki Y. Solvent dependence of absorption intensities and wavenumbers of the fundamental and first overtone of NH stretching vibration of pyrrole studied by near-infrared/infrared spectroscopy and DFT calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2011;115(7):1194–1198. doi: 10.1021/jp108548r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin F., Prieto A.C., De Saja J.A., Aroca R. SERS study of the pyrrole polymerization. J. Mol. Struct. 1988;174:363–368. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chowdhury P., Adhikary T.P., Chakravorti S. Effect of additives on the photophysics of 2-acetyl benzimidazole and 2-benzoyl benzimidazole encapsulated in cyclodextrin cavity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2005;173(3):279–286. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewandowski W., Świderski G., Świslocka R., Wojtulewski S., Koczoń P. Spectroscopic (Raman, FT-IR and NMR) and theoretical study of alkali metal picolinates. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2005;18(9):918–928. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J., Zhang X., Shaw A., Lu Q., Hu B., qing Dong C., ping Yang Y. Theoretical study of the effect of hydrogen radicals on the formation of HCN from pyrrole pyrolysis. J. Energy Inst. 2019;92:1468–1475. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsumoto Y., Honma K. NH stretching vibrations of pyrrole clusters studied by infrared cavity ringdown spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;127(18):184310. doi: 10.1063/1.2790894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coblentz W.W. Carnegie institute; Washington, DC: 1905. Investigation of Infra-red Spectra. [Google Scholar]

- 14.La Regina G., Bai R., Coluccia A., Famiglini V., Pelliccia S., Passacantilli S. New pyrrole derivatives with potent tubulin polymerization inhibiting activity as anticancer agents including hedgehog-dependent cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57(15):6531–6552. doi: 10.1021/jm500561a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasem K.K., Menges S., Jones S. Photoelectrochemical studies on poly [1-(2-aminophenyl) pyrrole]—Creation of a photoactive inorganic–organic semiconductor interface (IOI) Can. J. Chem. 2009;87(8):1109–1116. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abonia R., Insuasty B., Quiroga J., Kolshorn H., Meier H. A versatile synthesis of 4, 5-dihydropyrrolo [1, 2-a] quinoxalines. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2001;38(3):671–674. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruker APEX2, SAINT and SADABS.Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altomare A., Cascarano G., Giacovazzo C., Guagliardi A. Completion and refinement of crystal structures with SIR92. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993;26(3):343–350. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheldrick G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 2008;64(1):112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macrae C.F., Bruno I.J., Chisholm J.A., Edgington P.R., McCabe P., Pidcock E. Mercury CSD 2.0–new features for the visualization and investigation of crystal structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008;41(2):466–470. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrugia L.J. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1997;30:565. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G.A., Nakatsuji H., Caricato M., Li X., Hratchian H.P., Izmaylov A.F., Bloino J., Zheng G., Sonnenberg J.L., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Montgomery J.A., Jr., Peralta J.E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M., Heyd J.J., Brothers E., Kudin K.N., Staroverov V.N., Kobayashi R., Normand J., Raghavachari K., Rendell A., Burant J.C., Iyengar S.S., Tomasi J., Cossi M., Rega N., Millam J.M., Klene M., Knox J.E., Cross J.B., Bakken V., Adamo C., Jaramillo J., Gomperts R., Stratmann R.E., Yazyev O., Austin A.J., Cammi R., Pomelli C., Ochterski J.W., Martin R.L., Morokuma K., Zakrzewski V.G., Voth G.A., Salvador P., Dannenberg J.J., Dapprich S., Daniels A.D., Farkas Ö., Foresman J.B., Ortiz J.V., Cioslowski J., Fox D.J. Gaussian,Inc.; Wallingford CT: 2009. Gaussian 09W, Revision D.01. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becke A.D. A new mixing of Hartree–Fock and local density-functional theories. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98(2):1372–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee C., Yang W., Parr R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 1988;37(2):785. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.A. Frisch, A. B. Nielsen, A. J. Holder, Gauss View User's Manual Gaussian Inc., and Pittsburg.

- 26.Chemcraft - graphical software for visualization of quantum chemistry computations. https://www.chemcraftprog.com.

- 27.Fogarasi G., Pulay P. In: Durig J.R., editor. Vol. 14. 1985. p. 125. (Vibrational Spectra and Structure). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sundius T. MOLVIB: a program for harmonic force field calculations. J. Mol. Struct. 1990;218:321. QCPE program no. 604(1991) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Afzal A., Mohamed Shahin Thayyil Y.S.M., Shariq Mohammad, Resmi K.S., Thomas R., Islam N., Jyothi Abinu A. Anti-cancerous brucine and colchicine: experimental and theoretical characterization. Chemsitry Sel. 2019;4(2):11441–11454. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siji V.L., Sudarsanakumar M.R., Suma S., George A., Thomas P.V. 2011. FT-IR and FT-Raman spectral studies and DFT calculations of tautomeric forms of benzaldehyde-N (4)-phenylsemicarbazone.http://nopr.niscair.res.in/handle/123456789/11906 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-otaibi J.S., Mary Y.S., Mary Y.S., Thomas R. Quantum mechanical and photovoltaic studies on the cocrystals of hydrochlorothiazide with isonazid and malonamide. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1197:719–726. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sundaraganesan N., Illakiamani S., Meganathan C., Joshua B.D. Vibrational spectroscopy investigation using ab initio and density functional theory analysis on the structure of 3-aminobenzotrifluoride. Spectrochim. Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2007;67(1):214–224. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin-Vien D., Colthup N.B., Fately W.G., Grasselli J.G. Academic Press Boston; MA: 1991. The Handbook of Infrared and Raman Characteristic Frequencies of Organic Molecules. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Subashchandrabose S., Krishnan A.R., Saleem H., Thanikachalam V., Manikandan G., Erdoğdu Y. FT-IR, FT-Raman, NMR spectral analysis and theoretical NBO, HOMO–LUMO analysis of bis (4-amino-5-mercapto-1, 2, 4-triazol-3-yl) ethane by ab initio HF and DFT methods. J. Mol. Struct. 2010;981(1–3):59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar V.S., Mary Y.S., Pradhan K., Brahman D., Mary Y.S., Thomas R. Synthesis, spectral properties, chemical descriptors and light harvesting studies of a new bioactive azo imidazole compound. J. Mol. Struct. 2020;1199:127035. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mary Y.S., Mary Y.S., Resmi K.S., Thomas R. DFT and molecular docking investigations of oxicam derivatives. Heliyon. 2019;5(7):e02175. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas R., Mary Y.S., Resmi K.S., Narayana B., Sarojini S.B.K., Armaković S. Synthesis and spectroscopic study of two new pyrazole derivatives with detailed computational evaluation of their reactivity and pharmaceutical potential. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1181:599–612. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andraud C., Brotin T., Garcia C., Pelle F., Goldner P., Bigot B., Collet A. Theoretical and experimental investigations of the nonlinear optical properties of vanillin, polyenovanillin, and bisvanillin derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116(5):2094–2102. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Otaibi J.S., Mary Y.S., Mary Y.S., Panicker C.Y., Thomas R. Cocrystals of pyrazinamide with p-toluenesulfonic and ferulic acids: DFT investigations and molecular docking studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1175:916–926. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karamanis P., Pouchan C., Maroulis G. Structure, stability, dipole polarizability and differential polarizability in small gallium arsenide clusters from all-electron ab initio and density-functional-theory calculations. Phys. Rev. A. 2008;77(1):13201. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sagdinc S.G., Eşme A. Theoretical and vibrational studies of 4, 5-diphenyl-2-2 oxazole propionic acid (oxaprozin) Spectrochim. Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2010;75(4):1370–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dhas D.A., Joe I.H., Roy S.D.D., Freeda T.H. DFT computations and spectroscopic analysis of a pesticide: chlorothalonil. Spectrochim. Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2010;77(1):36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winget P., Thompson J.D., Cramer C.J., Truhlar D.G. Parametrization of a universal solvation model for molecules containing silicon. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2002;106(20):5160–5168. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mao S.C., Yin G.Q., Zheng K.C. Effect of electric field on the microcosmic properties of cation compound containing 2, 2, 6, 6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy and imidazole unit. J. Mol. Model. 2014;20(9):2423. doi: 10.1007/s00894-014-2423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lagunin A., Stepanchikova A., Filimonov D., Poroikov V. PASS: prediction of activity spectra for biologically active substances. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:747–748. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.8.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.AJM Nel, IM Tuffin, Sewell B.T., Cowan D.A. Unique Aliphatic Amidase from a Psychrotrophic and Haloalkaliphilic Nesterenkonia Isolate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:3696. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02726-10. LP-3702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duhovny D., Nussinov R., Wolfson H.J. Efficient unbound docking of rigid molecules. In: Gusfield, editor. Vol. 2452. Springer Verlag; 2002. pp. 185–200. (Proceedings of the 2'nd Workshop on Algorithms in Bioinformatics(WABI) Rome, Italy, Lecture Notes in Computer Science). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang C., Vasmatzis G., Cornette J.L., DeLisi C. Determination of atomic desolvation energies from the structures of crystallized proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267(3):707–726. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen R., Mintseris J., Janin J., Weng Z. A protein–protein docking benchmark. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 2003;52(1):88–91. doi: 10.1002/prot.10390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Connolly M.L. Analytical molecular surface calculation. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1983;16(5):548–558. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beegum S., Mary Y.S., Mary Y.S., Thomas R., Armakovi S., Armakovi S.J., Zitko J., Dolezal M., Van Alsenoy C. Exploring the detailed spectroscopic characteristics, chemical and biological activity of two cyanopyrazine-2-carboxamide derivatives using experimental and theoretical tools. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020;224:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2019.117414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mary Y.S., Mary Y.S., Thomas R., Narayana B., Samshuddin S., Sarojini B.K., Armaković S., Armaković S.J., Pillai G.G. Theoretical Studies on the Structure and Various Physico-Chemical and Biological Properties of a Terphenyl Derivative with Immense Anti-Protozoan Activity. Polycycl. Aromat. Comp. 2019 In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kavitha Rani P R., Mary Y.S., Fernandez A., S A.P., Mary Y.S., Thomas R. Single crystal XRD, DFT investigations and molecular docking study of 2- ((1,5-dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)amino)naphthalene-1,4-dione as a potential anti- cancer lead molecule. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2019;78:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2018.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hossain M., Thomas R., Mary Y.S., Resmi K.S., Armaković S., Armaković S.J., Nanda A.K., Vijayakumar G., Alsenoy C.V. Understanding reactivity of two newly synthetized imidazole derivatives by spectroscopic characterization and computational study. J. Mol. Struct. 2018;1158:176–196. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jeeva S., Muthu S., Thomas R., Raajaraman B.R., Mani G., Vinitha G. Co-crystals of urea and hexanedioic acid with third-order nonlinear properties: An experimental and theoretical enquiry. J. Mol. Struct. 2020;1202:127237. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomas R., Hossain M., Mary Y.S., Resmi K.S., Armaković S., Armaković S.J., Nanda A.K., Ranjan V.K., Vijayakumar G., Van Alsenoy C. Spectroscopic analysis of 8-hydroxyquinoline derivatives and investigation of its reactive properties by DFT and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Struct. 2018;1156:336–347. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mary Y.S., Mary Y.S., Resmi K.S., Kumar V.S., Thomas R., Sureshkumar B. Detailed quantum mechanical, molecular docking, QSAR prediction. Heliyon. 2019;5 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haruna K., Kumar V.S., Sheena Mary Y., Popoola S.A., Thomas R., Roxy M.S., Al-Saadi A.A. Conformational profile, vibrational assignments, NLO properties and molecular docking of biologically active herbicide1,1-dimethyl-3-phenylurea. Heliyon. 2019;5 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.