Dear Editor,

The benefit of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in the treatment of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is still under investigation, and randomized control trials worldwide are currently recruiting patients. Data on HCQ pharmacokinetics (PK) exist in lupus patients but are scarce in COVID-19 critically ill patients [1–3]. In our intensive care unit (ICU), patients were started on a 10-day oral course of HCQ 200 mg t.i.d, or 200 mg b.i.d if they had acute kidney injury (AKI) defined as creatinine clearance < 50 ml/min [4]. Oral loading dose was 400 mg, or 200 mg if patients had AKI. We targeted trough blood concentrations between 1 and 2 mg/L [4, 5]. HCQ can induce critical side effects such as prolonged QT on electrocardiogram (EKG), severe arrhythmias, and hypoglycemia. This toxicity combined with lack of experience using HCQ led us to measure daily blood trough and peak concentrations over a 12-day period to evaluate PK parameters. Samples were also collected around first hemodialysis (HD) session and in dialysis bath.

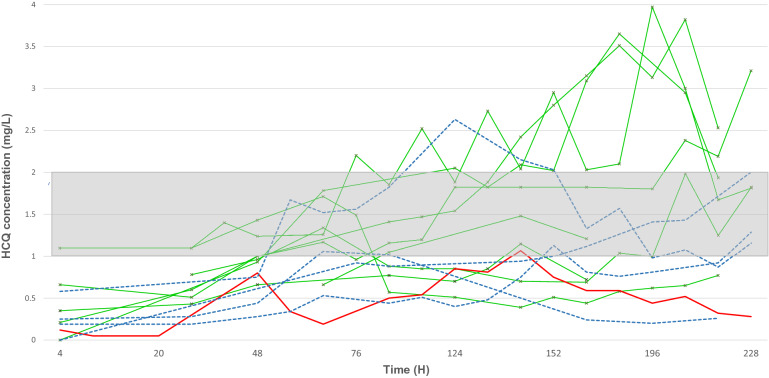

We included eight patients with normal renal function, five patients with AKI of whom four required renal replacement therapy and one patient with veno-venous extracorporeal life support (ECLS) (eFig. 2). Median age was 58 (interquartile range 53–70) years, seven (50%) male, and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score at admission was 5 (3–7). At day one of treatment, all patients were mechanically ventilated. Median albumin level was 27 (24–30) g/L, and total bilirubin serum level was 6 (4–8.5) µmol/l (eTable 1). We found median HCQ peak concentrations after loading dose of 400 mg and 200 mg were 0.5 (0.28–0.62) mg/L and 0.22 (0.2–0.24) mg/L, respectively (eTable 2). Median time to obtain concentration of 1 mg/L was 4 (3–7) days (Fig. 1), and median duration in therapeutic range was 3.3 days. Toxic levels were noted after day five of treatment (Fig. 1). We found unchanged HCQ concentrations before and after HD sessions and low HCQ concentration in dialysis bath: 0.01 mg/L and 0.032 mg/L at half-time and at disconnection of dialysis line, respectively. Finally, three out of 14 patients (21%) with blood concentration in therapeutic range had side effects: two with prolonged QT who needed a treatment cessation and one with severe hypoglycemia who required a decreased HCQ dosage.

Fig. 1.

Hydroxychloroquine pharmacokinetics over a period of ten days in fourteen ICU patients. Red line represents one patient with veno-venous extracorporeal life support (ECLS), green lines depict patients with normal renal function and blue dash curves show patients with acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy. Therapeutic zone is the gray area between 1 mg/L and 2 mg/L. Overall, 212 HCQ levels were analyzed over the study period. All patients but one (93%) achieved minimum therapeutic level. After 124 h, patients are more at risk of having residual and peak levels in the toxic zone, i.e., 2 mg/L. The patient with veno-venous ECLS remains under the lower therapeutic level of 1 mg/L

Our results suggest that prescribing HCQ in COVID-19 patients is unsafe for several reasons. Because of drug accumulation and high volume of distribution, toxic threshold was reached by day 5 even in patients with normal renal function. We recorded side effects although patients’ blood concentrations were in therapeutic range, therefore making HCQ administration potentially harmful despite correct surveillance parameters. HD had little effect on HCQ concentrations, whereas the patient with ECLS expressed constant low HCQ blood concentration, possibly due to membrane adsorption. To avoid HCQ-related complications in COVID-19 critically ill patients, we suggest monitoring EKG and blood concentration daily. In summary, we believe that for safety reasons, HCQ should not be prescribed outside of randomized controlled trials anymore.

The local ethics committee approved the study (Institutional Review Board of the Rennes University Hospital, accord no 20.38). All patients signed written informed consent.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contribution

BP conceptualized the study and participated in its design, data acquisition and analysis, literature research, and manuscript drafting. PG participated in data acquisition and analysis, literature research, and manuscript drafting. MCV participated in data acquisition and analysis and manuscript drafting. AG participated in data acquisition and analysis, revising of the article for important intellectual content, and manuscript drafting. AM participated in data acquisition and analysis, revising of the article for important intellectual content, and manuscript drafting. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Al-Rawi H, Meggitt SJ, Williams FM, Wahie S. Steady-state pharmacokinetics of hydroxychloroquine in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2018;27:847–852. doi: 10.1177/0961203317727601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perinel S, Launay M, Botelho-Nevers É, et al. Towards optimization of hydroxychloroquine dosing in intensive care unit COVID-19 patients. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Cremades M, Solans BP, Hughes E, et al. Optimizing hydroxychloroquine dosing for patients with COVID-19: an integrative modeling approach for effective drug repurposing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020 doi: 10.1002/cpt.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durcan L, Clarke WA, Magder LS, Petri M. Hydroxychloroquine blood levels in systemic lupus erythematosus: clarifying dosing controversies and improving adherence. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:2092–2097. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao X, Ye F, Zhang M, et al. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.