Abstract

Introduction:

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears are among the most common orthopedic injuries. In the demanding athletic patient, autograft ACL reconstruction is recognized as the gold standard treatment. However, there is a renewed interest in the preservation and repair of the torn ACL. Despite good to excellent clinical short-to mid-termresults of ACL primary repair, there are currently no reports of a successful secondary ACL repair following a retear of a primary ACL repair.

Case Report:

We report the successful secondary ACL repair of a 47-year-old athletic female patient who initially fell while skiing, suffering a left proximal ACL tear that was subsequently treated with an arthroscopic ACL repair using internal brace augmentation. The patient was administered to intensive post-operative physiotherapy and aquatic therapy as well as continuous follow-up visits where the pain-free patient demonstrated a full range of motion with negative Lachman, Drawer, and pivot shift tests. Ten weeks postoperatively, the patient returned to sports – including alpine skiing 3 months postoperatively. Just 1 week after, her 1-year follow-upvisit, the patient experienced another severe ski fall suffering a proximal ACL retear to her left knee. She underwent arthroscopic ACL repair using internal brace augmentation on the same day. The patient returned to sports 10-week post-injury and demonstrated a full range of knee motion, negative Lachman, Drawer, and pivot shift tests with a 1.0mm side-to-side laxity difference at 12-month follow-up with good subjective outcome parameters: International Knee Documentation Committee score of 83, Lysholm score of 95, and a pre-and post-operative Tegner score of 7. Again, she returned to alpine skiing 3 months postoperatively.

Conclusion:

Arthroscopic ACL re-repair using internal brace augmentation is feasible and provides objective and subjective short-term clinical success as a revision surgery for primary ACL repair with internal brace augmentation. However, critical patient selection – including assessment of the ACL retear pattern and tissue quality – and prompt surgery are essential.

Keywords: Anterior cruciate ligament repair, anterior cruciate ligament re-repair, anterior cruciate ligament revision surgery, anterior cruciate ligament internal brace

Learning Point of the Article:

Secondary ACL repair provides objective and subjective short-term success as a revision surgery for primary ACL repair.

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears are a common orthopedic injury with a reported annual incidence of 68.6/100.000 person-years [1]. In the demanding athletic patient, autograft ACL reconstruction using a hamstring or patellar tendon is recognized as the gold standard treatment [2, 3, 4]. However, there is a renewed interest in the preservation and repair of the torn ACL [5]. Despite good to excellent clinical short- to mid-termresults of ACL primary repair, there are currently no reports of a successful secondary ACL repair following a retear of a primary ACL repair [6].

We report the first case of an ACL re-repair with good to excellent subjective and objective short-term results following a traumatic retear of a previously repaired ACL 1 year prior.

Case Report

A 47-year-old athletic female patient (165cm; 63kg) was referred to our trauma department by ambulance after she fell twisting her left knee while downhill skiing at high speed.

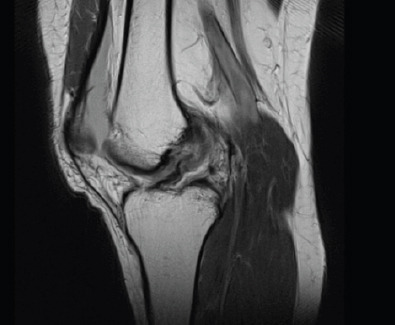

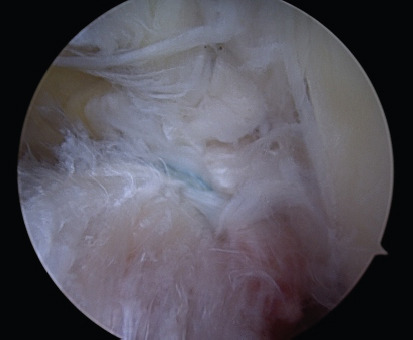

Clinical examination revealed a moderate effusion of the left knee with a positive Lachman, Drawer, and pivot shift test. Radiographic examination showed regular bony configuration of the left knee with no associated fractures while magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed a proximal ACL tear with no evidence of concomitant chondral/ meniscal/ ligamentous injuries (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imagingT1-weighted image confirming the proximal anterior cruciate ligament tear with good tissue quality.

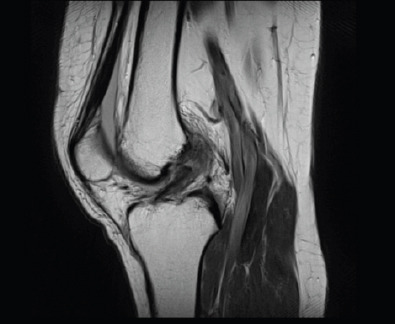

The patient underwent a knee arthroscopy on the same day where the radiological findings were confirmed. The ACL tear presented with a proximal tear pattern (Sherman type 1), good tissue quality, and an intact synovial coverage so that an arthroscopic ACL repair using internal brace augmentation was performed (see surgical technique below, Fig. 2, 3, 4).

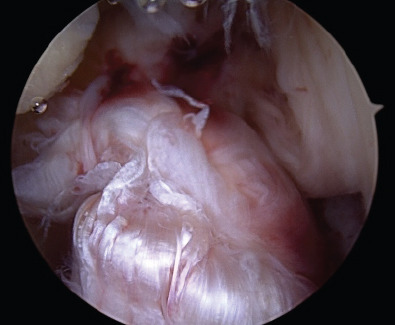

Figure 2.

Arthroscopic view of the anterior cruciate ligament tear with a proximal tear pattern (Sherman type 1), good tissue quality, and an intact synovial coverage.

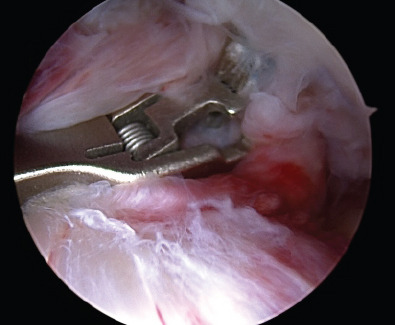

Figure 3.

The labral Scorpion suture passer (Arthrex; Naples, USA) is used to pass a No. 2 FiberWire® (Arthrex; Naples, USA) through the anterior cruciate ligament remnant.

Figure 4.

Completed anterior cruciate ligament repair using internal brace augmentation.

Postoperatively, the left knee was immobilized in a neoprene splint for 2 days only with full weight-bearing as tolerated on crutches for 6 weeks. Passive mobilization of the knee started immediately on the 1stpost-operative day followed by increasing active and assistive mobilization. Knee flexion was limited to 90 degrees for 4 weeks. Physiotherapy (3 times a week) and aquatic therapy (once a week) completed the post-operative care.

The patient was discharged in good general condition with a total inpatient stay of 2 days. The 6-week follow-up assessment showed negative Lachman and pivot shift tests, a 1.0mm side-to-side laxity (left side: 6mm, right side 5mm) measured with the KT-1000 arthrometer (MED metric Corp; San Diego, USA) and a restricted knee flexion of 100 degrees while 6-monthfollow-up assessment demonstrated a considerably improved range of movement with 120 degrees of knee flexion. At 1-year follow-up assessment, the pain-and complaint-free patient demonstrated a full range of knee motion and no signs of instability were observed.

The patient started with running and cycling exercises 8-week postoperatively and returned to alpine skiing 3 months postoperatively.

However, just 1 week after, her 1-year follow-up visit, the patient experienced another severe ski fall with twisting of the left knee and an immediate audible popping noise. A large hemarthrosis developed and patient clinically demonstrated with a positive Lachman, Drawer, and pivot shift test. Consequently, an MRI scan confirmed the diagnosis of a proximal ACL retear (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Magnetic resonance imagingT1-weighted image confirming the proximal anterior cruciate ligamentretear again, with good tissue quality.

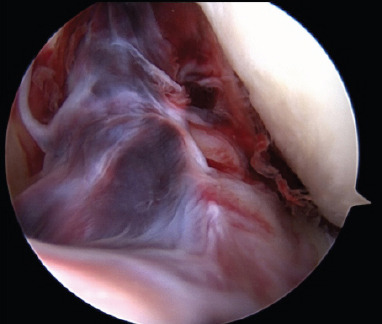

The patient underwent emergent knee arthroscopy – just 5 h after injury. Intraoperatively, the ACL retear presented with a replicated proximal tearpattern (Sherman type 1), good tissue quality, and an intact synovial coverage so that an arthroscopic ACL re-repair using internal brace augmentation was performed (Fig. 6, 7, 8).

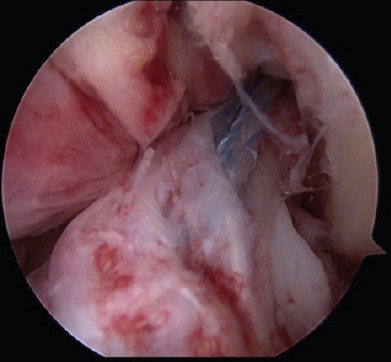

Figure 6.

Arthroscopic view of the anterior cruciate ligamentretear with a proximal tear pattern (Sherman type 1), good tissue quality, and an intact synovial coverage.

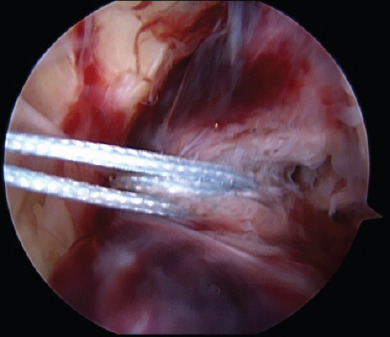

Figure 7.

A No. 2 FiberWire® (Arthrex; Naples, USA) suture is passed through the anterior cruciate ligament remnant with a labral scorpion suture passer (Arthrex; Naples, USA).

Figure 8.

Completed anterior cruciate ligament repair using internal brace augmentation.

Again, the patient was very motivated and compliant with physiotherapy returning to sports 10-week post-injury and alpine skiing 3 months postoperatively. The patient demonstrated a full range of knee motion and negative instability tests with a 1.0mm side-to-side laxity difference (left side: 6mm, right side 5mm) at 6-and 12-month follow-up, respectively. The subjective outcome parameters remained good at 12-month follow-up with the International Knee Documentation Committee score of 83, Lysholm score of 95, and a pre-and post-operative Tegner score of 7. MRI at 12-monthfollow-up confirmed the integrity of the repaired ACL (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Magnetic resonance imagingT1-weighted image at 12-month follow-up confirming the integrity of the re-repairedanterior cruciate ligament.

Surgical technique

The two knee arthroscopies were performed with the patient in supine position under spinal anesthesia and the affected left leg placed in an adjustable leg holder. An additional knee examination under anesthesia confirmed the positive Lachman, Drawer, and pivot shift before arthroscopy.

A hemarthrosis was drained on insertion of the arthroscopic cannula in both cases. Using the two standard anterolateral and anteromedial portals, an arthroscopic washout as well as a diagnostic arthroscopy were performed confirming the radiographically suspected findings with a hook probe. The ACL was carefully assessed, including tear pattern, tissue quality, and synovial coverage of the ACL remnant: Aproximal ACL tear (Sherman Type 1) with good tissue quality and an intact synovial coverage as well as no concomitant osteochondral lesions nor meniscal injuries were present in both arthroscopies (Fig. 2 and 6).

An ACL repair utilizing an internal brace augmentation was performed in both cases as popularized by van der List and DiFelice [5]: Using a labral scorpion suture passer (Arthrex; Naples, USA), a No. 2 Fiber Wire® (Arthrex; Naples, USA) was passed 3 times through the ACL remnant – approximately 1cm distal to the ACL tear (Fig. 3 and 7). The femoral tunnel was drilled in an anatomic manner at the femoral footprint with 130degrees knee flexion using a spade tip drill pin (Arthrex; Naples, USA) and a shuttling loop was subsequently passed through the femoral tunnel. The tibial drilling guide (Smith and Nephew, London, United Kingdom) was then placed at the anterior center of the ACL tibial footprint and the tibial tunnel was drilled through a small skin incision on the anteromedial aspect of the tibia. A shuttling loop was passed through the tibial tunnel. A suture retriever (Arthrex; Naples, USA) was placed through the anteromedial portal retrieving the tibial shuttling loop. The femoral shuttling loop as well as the Fiber Wire® suture were then placed into the tibial shuttling loop and passed through the tibial tunnel. Using the femoral and tibial shuttling loop, the Internal Brace construct consisting of a Tight Rope®(Arthrex; Naples, USA) armed with a Fiber Tape®(Arthrex; Naples, USA) and the Fiber Wire® suture was carefully shuttled through the tibia and femur so that the Tight Rope® button flipped at the femoral cortex (Figs. 4 and 8).

With the knee in full extension, a bone socket was prepared for a 4.75mm Swive Lock®(Arthrex; Naples, USA) anchor to fix the Fiber Tape®at the anteromedial tibial skin incision. Afterward, the Fiber Wire® suture was knotted on tension to the Tight Rope® tensioning suture with a knot pusher.

An arthroscopic awl with a 45 degrees angle was used to perform focused microfracture near the femoral ACL footprint to allow the formation of a cancellous bleeding bed to enhance healing.

Discussion

An ACL tear is a common injury in the active population with a reported annual incidence of 68.6/100.000 person-years [1]. Although the optimal management of an ACL tear remains controversial, surgical treatment is recommended, particularly in the demanding athletic patient [4].

Various surgical techniques have been described and the procedures have considerably evolved over the past decades [7]: While the common treatment in the 1970s and 1980s was the open ACL repair, the ACL reconstruction using an autologous hamstring or patellar tendon is today accepted as the gold standard. Despite good to excellent functional results after ACL reconstruction, there has been a renewed interest in the preservation and arthroscopic repair of the torn ACL [5, 8, 9].

The renewed interest in ACL repair is due to an improved understanding of the eligible patient for this procedure: Aproximal tear pattern and good tissue quality of the ACL remnant as well as prompt surgery are essential for a successful arthroscopic ACL repair [8, 9, 10]. In addition, the arthroscopic ACL repair offers several advantages over the ACL reconstruction such as the preservation of the proprioceptive function of the ACL, an avoidance of grafting morbidities, and a faster recovery protocol [8, 9]. In a systematic review, van Eck et al. have confirmed the healing potential for arthroscopic ACL repair in the “well-defined subset of patients” and have emphasized that an additional internal bracing and bone marrow access can further increase the success rate in ACL repair [11].

Despite critical patient selection and prompt surgery, there is always the risk for an ACL retear in ACL repair as it is in ACL reconstruction. Paterno et al. have shown in a prospective case–control study that the risk of an ACL retear following ACL reconstruction is significantly increased compared to a healthy population [12]. In addition, Gifstad et al. have shown significantly lower functional and subjective outcome results in patients undergoing ACL reconstruction revision surgery compared to patients undergoing primary ACL reconstruction [13].

As ACL repair is becoming increasingly popular in the soft tissue knee community, only little information on specific retear rates, subsequent revision surgeries, and the later outcome are available. Heusdens et al. have reported a retear in 2of 42 patients following arthroscopic ACL repair with internal brace augmentation –both patients underwent subsequent ACL reconstruction [14]. DiFelice et al. reported one failure after primary ACL repair in 11patients but give no information on the necessity of a subsequent revision surgery [10]. Despite only little information, ACL reconstruction is recognized as the regular revision surgery following failed primary ACL repair [15].

Although there have been no previous reports of a successful ACL re-repair as a revision surgery for a failed primary ACL repair, we performed this surgery after carefully weighing pros and cons with our patient. The main reasons for doing so were the informed consent of our patient (that was very satisfied with the functional outcome of the primary ACL repair), the type of trauma (severe ski fall with no signs of instability at the regular follow-up visits), as well as the intraoperative findings (proximal tear pattern, good tissue quality, and intact synovial coverage).

Conclusion

We provide the first case of an arthroscopic ACL re-repair as a revision surgery for primary ACL repair. Using internal brace augmentation, good to excellent objective and subjective short-term results can be achieved. However, critical patient selection – including assessment of the ACL retear pattern and tissue quality – is essential.

Clinical Message.

Arthroscopic ACL re-repair using internal brace augmentation is feasible and provides objective and subjective short-term clinical success as a revision surgery for primary ACL repair in patients with a proximal retear pattern and good tissue quality.

Biography

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Nil

Source of Support: Nil

Consent: The authors confirm that Informed consent of the patient is taken for publication of this case report

References

- 1.Sanders TL, MaraditKremers H, Bryan AJ, Larson DR, Dahm DL, Levy BA, et al. Incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears and reconstruction:A 21-year population-based study. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:1502–7. doi: 10.1177/0363546516629944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aglietti P, Giron F, Buzzi R, Biddau F, Sasso F. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction:Bone-patellar tendon-bone compared with double semitendinosus and gracilis tendon grafts. A prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:2143–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fithian DC, Paxton EW, Stone ML, Luetzow WF, Csintalan RP, Phelan D, et al. Prospective trial of a treatment algorithm for the management of the anterior cruciate ligament-injured knee. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:335–46. doi: 10.1177/0363546504269590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krause M, Freudenthaler F, Frosch KH, Achtnich A, Petersen W, Akoto R, et al. Operative versus conservative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. DtschArztebl Int. 2018;115:855–62. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der List JP, DiFelice GS. Arthroscopic primary anterior cruciate ligament repair with suture augmentation. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6:e1529–34. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoogeslag RAG, Brouwer RW, Boer BC, de Vries AJ, Huis In't Veld R. Acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture:Repair or reconstruction?Two-year results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:567–77. doi: 10.1177/0363546519825878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambat P, Guier C, Sonnery-Cottet B, Fayard JM, Thaunat M. The evolution of ACL reconstruction over the last fifty years. Int Orthop. 2013;37:181–6. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1759-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der List JP, Jonkergouw A, van Noort A, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, DiFelice GS. Identifying candidates for arthroscopic primary repair of the anterior cruciate ligament:A case-control study. Knee. 2019;26:619–27. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der List JP, DiFelice GS. Primary repair of the anterior cruciate ligament:A paradigm shift. Surgeon. 2017;15:161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiFelice GS, Villegas C, Taylor S. Anterior cruciate ligament preservation:Early results of a novel arthroscopic technique for suture anchor primary anterior cruciate ligament repair. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:2162–71. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Eck CF, Limpisvasti O, ElAttrache NS. Is there a role for internal bracing and repair of the anterior cruciate ligament?A systematic literature review. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:2291–8. doi: 10.1177/0363546517717956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paterno MV, Rauh MJ, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Incidence of contralateral and ipsilateral anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury after primary ACL reconstruction and return to sport. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22:116–21. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318246ef9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gifstad T, Drogset JO, Viset A, Grøntvedt T, Hortemo GS. Inferior results after revision ACL reconstructions:A comparison with primary ACL reconstructions. Knee Surg Sports TraumatolArthrosc. 2013;21:2011–8. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2336-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heusdens CHW, Hopper GP, Dossche L, Roelant E, Mackay GM. Anterior cruciate ligament repair with independent suture tape reinforcement:A case series with 2-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports TraumatolArthrosc. 2019;27:60–7. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherman MF, Lieber L, Bonamo JR, Podesta L, Reiter I. The long-term followup of primary anterior cruciate ligament repair. Defining a rationale for augmentation. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:243–55. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]